Abstract

Changes to the global food supply have been characterized by greater availability of edible oils, sweeteners, and meats—a profound “nutrition transition” associated with rising obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Through an analysis of three longitudinal databases of food supply, sales and economics across the period 1961–2010, we observed that the change in global food supply has been characterized by a dramatic rise in pig meat consumption in China and poultry consumption in North America. These changes have not been experienced by all rapidly-developing countries, and are not well explained by changes in income. The changes in food supply include divergence among otherwise similar neighboring countries, suggesting that the changes in food supply are not an inevitable result of economic development. Furthermore, we observed that the nutrition transition does not merely involve an adoption of “Western” diets universally, but can also include an increase in the supply of edible oils that are uncommon in Western countries. Much of the increase in sales of sugar-sweetened beverages and packaged foods is attributable to a handful of multinational corporations, but typically from products distributed through domestic production systems rather than foreign importation. While North America and Latin America continued to have high sugar-sweetened beverage and packaged food sales in recent years, Eastern Europe and the Middle East have become emerging markets for these products. These findings suggest further study of natural experiments to identify which policies may mitigate nutritional risk factors for chronic disease in the context of economic development.

Introduction

Changes to the global food supply have been characterized by a dramatic shift in foods available for human consumption, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (Drewnowski & Popkin, 1997). The changes in food supply include greater availability of edible oils, caloric sweeteners, and animal source foods. These changes, collectively called the “nutrition transition”, have been statistically associated with rising obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease worldwide (S. Basu, Stuckler, McKee, & Galea, 2012; Sanjay Basu, Yoffe, Hills, & Lustig, 2013; Sanjay Basu, Yoffe, et al., 2013; Popkin, 2001; Reddy & Yusuf, 1998; Yusuf, Reddy, Ôunpuu, & Anand, 2001).

Changes to the food supply have sparked increasing public concern about the nutrient quality of food availability around the world, the underlying factors such as trade agreements that are believed to be driving the nutrition transition in rapidly-developing countries, and the role of “Big Food” companies who manufacture and widely-distribute processed foods associated with disease (D. Stuckler, McKee, Ebrahim, & Basu, 2012). Three key questions about the food supply are emerging in the setting of debates about how to best address the nutrition transition and Big Food companies. First, to what extent has the nutrition transition—described decades ago (Popkin, 1994)—continued, accelerated, or been mitigated among low- and middle-income countries in more recent years? The transition has been hypothesized to be accelerating in countries like India and China, where increasing consumption of Western-type diets is thought to be occurring in the context of rapid economic growth (Yang et al., 2010). Second, have all rapidly-developing countries undergone the same transition, or is the transition different among similar countries? If similar countries are undergoing different transitions—for example, if healthier foods are more available in one country than in neighboring countries undergoing similar social and economic changes—then differences in food supply may not be “inevitable” consequences of economic development, but a product of specific policy choices. Third, what aspects of the transition are related to the actions of Big Food companies? Identifying which foods and companies are associated with increased unhealthy food supply may help identify future policy choices, reducing the impact of the nutrition transition on obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.

Here, we address these three questions using longitudinal datasets describing food supply and food sales data from around the world. Because the nutrition transition has been particularly characterized by changes in the consumption of meats, edible oils, vegetables, and sugars, we particularly focused on these food groups in our analysis.

Methods

Data sources

We linked three large international longitudinal datasets for our analysis. First, we used the UN Food and Agricultural Organization’s (FAO) food balance sheets, which describe food supply among 216 countries from 1961 through 2007 in each of several standardized food groups (Food and Agricultural Organization, 2014). Second, we used the Euromonitor Passport Global Market Information (GMI) Database, which describes food sales per capita per year from 1997 through 2010 for each of several packaged or canned food products among 88 countries (Euromonitor International, 2013). Third, we used the World Bank World Development Indicators Database, which describes each country’s gross domestic product per capita and dollars spent per year on food imports from 1961 through 2010 (World Bank, 2014).

Data analyses

We first analyzed trends in food supply per capita in the FAO database for each of eight food categories within each country: cereals, sugar/sweeteners, meats, dairy/milk, fruits, vegetables, edible fats/oils, and fish/seafood. Food supply was expressed in kilocalories per capita per day, including only food directed to human consumption, excluding food waste and food crops directed to products not for human consumption (e.g., animal feed).

We next conducted product-specific analyses of food sales in the GMI Database, focusing on beverages and packaged food products, with food sales expressed in exchange-rate-adjusted US dollars in purchasing power parity for comparability across countries, and in terms of net units sold per capita (US gallons for beverages, US tons for solid foods). We compared how food supply and food sales varied across regions and within regions, using World Bank classifications of countries into geographic blocks.

We finally regressed both food supply and food sales against GDP per capita and food import dollars to evaluate the correlations between income, food importation, supply and sales, conducting fixed effects regressions to correct for time-invariant differences between countries. We specifically focused on GDP for this analysis because—while there are numerous changes associated with the nutrition transition (urbanization, agriculture changes, etc.), we specifically wished to determine whether GDP transitions routinely resulted in consistent nutrition transitions across countries, or if some countries underwent GDP increases without experiencing dramatic nutrition transitions. We report all regression results using population weights and robust standard errors clustered by country. We conducted all analyses in Stata MP v. 12.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

Results

Trends in the nutrition transition

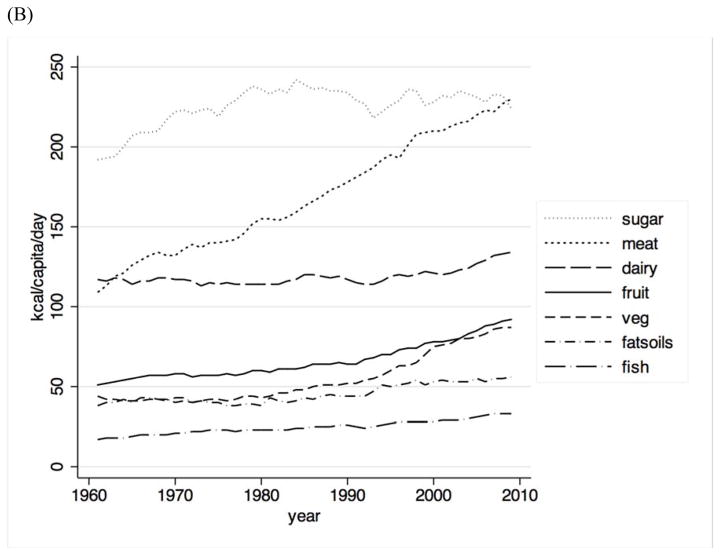

Changes in the food supply worldwide over the past five decades are illustrated in Figure 1. The greatest change in supply was the 204% rise in the supply of meat products—an increase from 109 kilocalories per capita per day in 1961 to 222 kilocalories per capita per day in 2007.

Figure 1.

Changes to food supply worldwide (A) in all major food groups; and (B) with cereals excluded to allow closer visualization of the rise in meat supply.

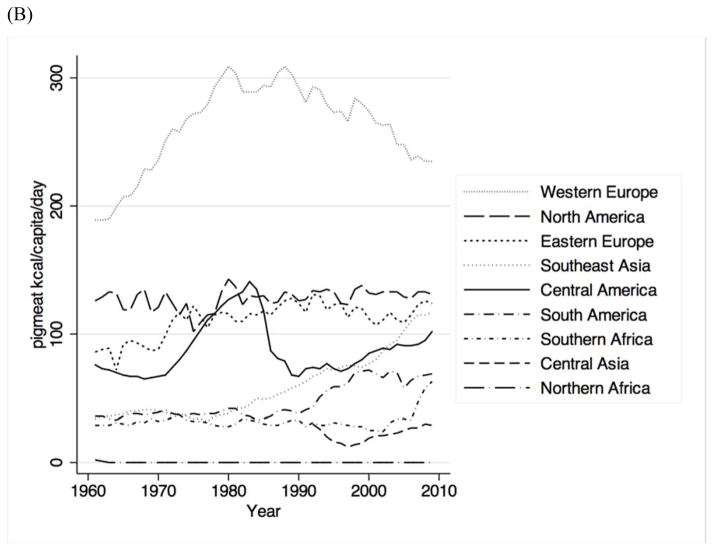

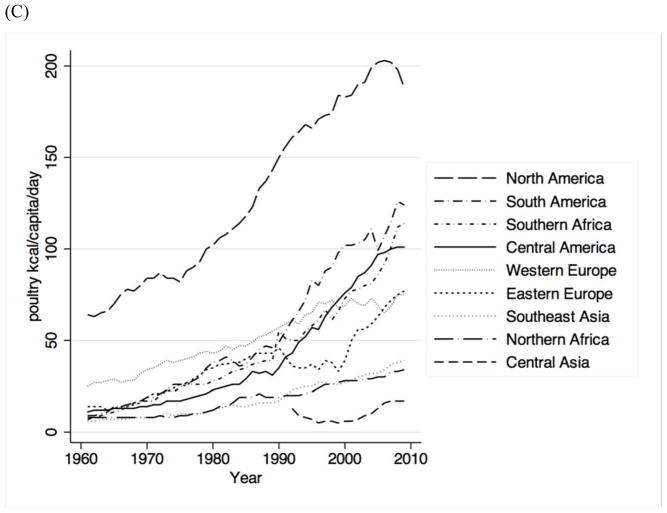

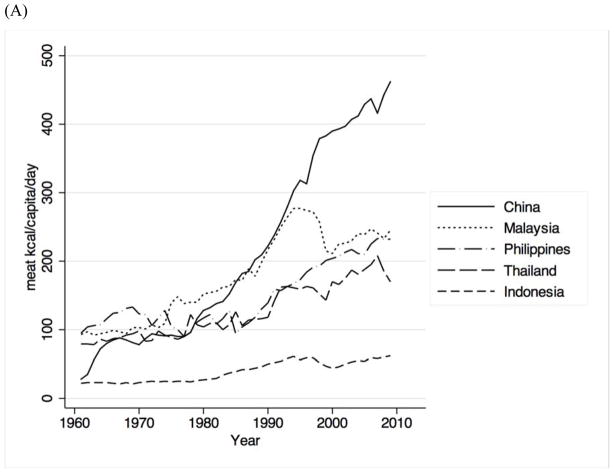

The large increase in meat supply was mostly in the form of pig meat and poultry meat, as shown in Figure 2. The increased meat supply in the form of pig meat occurred primarily in Southeast Asia, as shown in the Figure. While pig meat supplies increased most substantially in China, the supplies simultaneously decreased in Western European and Central American countries. By contrast, the increase in poultry meat supply occurred in nearly all world regions, as shown in Figure 2. The increase in poultry meat was greatest in North America, where poultry meat consumption increased 316% from 64 kilocalories per capita per day in 1961 to 202 kilocalories per capita per day in 2007. As shown in the Figure, increases in poultry meat supply also occurred to a lesser extent in Africa, Latin America and Eastern Europe.

Figure 2.

Rise in meat supply (A) worldwide; (B) specifically for pig meat, disaggregated by region; and (C) specifically for poultry meat, disaggregated by region.

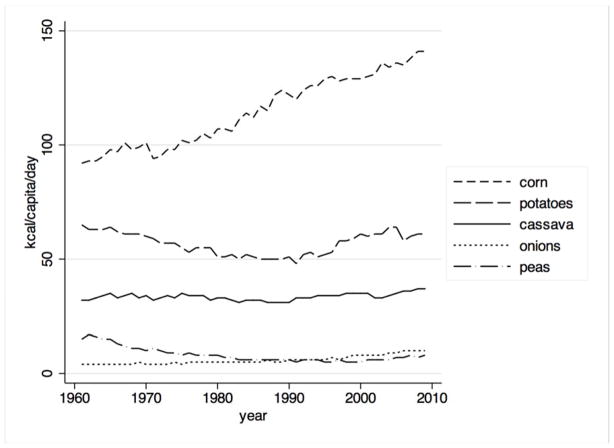

While smaller than the increase in meat supply, the vegetable supply also increased worldwide, as shown in Figure 3. The increase in vegetable supply was mostly in the form of corn and maize products. The increase in corn and maize products were greatest in North and West Africa, where a net increase of approximately 100 kilocalories per capita per day occurred between 1961 and 2007 in the context of large international aid shipments (i.e., not domestic production). Apart from these increases, further increases in vegetable supply per capita were also observed in Southeast Asia to a lesser extent.

Figure 3.

Vegetable supply changes worldwide.

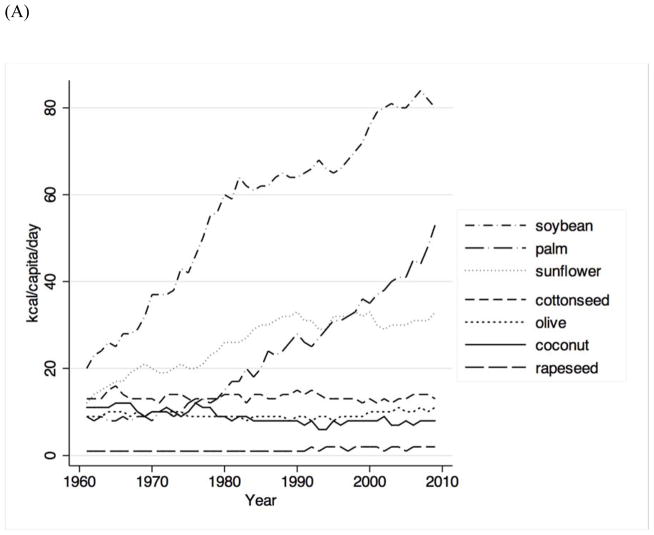

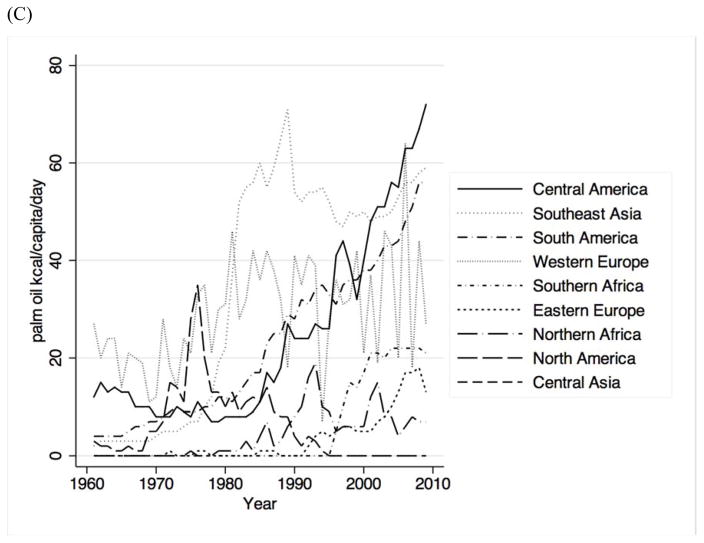

In addition to changes in the meat and vegetable supply, a third notable transition worldwide was a change in edible oils, as shown in Figure 4. The increase in edible oils was mostly in the form of soybean and palm oils. As shown in the Figure, the increase in soybean oil was observed mostly in Central Asia and Latin America, while palm oil supply increases were observed more in Southeast Asia and Latin America.

Figure 4.

Edible oil supply changes (A) worldwide; (B) specifically for soybean oil, disaggregated by region; and (C) specifically for palm oil, disaggregated by region.

Variations among countries in the nutrition transition

We found that many low- and middle-income countries diverged from each other over the last five decades in terms of the changes in the food supply they experienced. The countries experiencing the largest changes in food supply within each of the major food groups are summarized in Table 1. As shown in the Table, countries experiencing the largest changes in cereals were mostly African and Middle Eastern countries receiving large international aid shipments. However, variation in meat consumption appeared to be driven more by domestic production. As shown in the Table and in Figure 5, China was unique among Asian countries in experiencing a large and sustained increase in meat supply per capita, mostly from domestic pig meat, while other Asian countries experienced a larger increase in sugar and sweetener supplies. For example, while China experienced a rise in meat consumption of over 350 kilocalories per capita per day from 1961 to 2007, South Korea and Thailand experienced smaller increases of 228 and 129 kilocalories per capita per day, respectively, even though all three countries experienced similar GDP per capita increases of around 160% during the period. China experienced a rise in the sugar supply of 62 kilocalories per capita per day, versus 309 in South Korea and 264 in Thailand during the period 1961–2007, mostly in the form of imported sugar-containing products.

Table 1.

Countries experiencing the largest changes in food supply in each food group, 1961–2007.

| Country | Food group | Increase in Kcals/capita/day, 1961–2007 |

|---|---|---|

| Cereals | ||

| Palestine | 1162 | |

| Burkina Faso | 936 | |

| Algeria | 728 | |

| Egypt | 678 | |

| China | 636 | |

| Sugars | ||

| South Korea | 309 | |

| Thailand | 264 | |

| Syria | 261 | |

| Saudi Arabia | 253 | |

| Palestine | 247 | |

| Meats | ||

| China | 388 | |

| Saint Lucia | 358 | |

| Spain | 352 | |

| Saint Vincent | 317 | |

| Portugal | 310 | |

| Samoa | 307 | |

| Dairy | ||

| Albania | 300 | |

| Romania | 287 | |

| Greece | 252 | |

| Dominica | 214 | |

| Cape Verde | 208 | |

| Fruits | ||

| Dominica | 188 | |

| Sao Tome and Principe | 182 | |

| Thailand | 178 | |

| Cuba | 154 | |

| United Arab Emirates | 142 | |

| Vegetables | ||

| China | 134 | |

| South Korea | 113 | |

| Iran | 110 | |

| Palestine | 95 | |

| Malta | 93 | |

| United Arab Emirates | 90 | |

| Fats and oils | ||

| Vanuatu | 176 | |

| Central African | 107 | |

| Gabon | 95 | |

| Benin | 94 | |

| Samoa | 92 | |

| Fish | ||

| Maldives | 268 | |

| South Korea | 76 | |

| Malaysia | 66 | |

| Kiribati | 65 | |

| Micronesia | 65 | |

| Total kcals | ||

| Palestine | 2240 | |

| Libya | 1562 | |

| Colombia | 1531 | |

| Algeria | 1443 | |

| Dominica | 1411 | |

| Iran | 1363 | |

Figure 5.

Intraregional supply changes: (A) in meat supply in Southeast Asia; (B) by contrast, relative stability in meat supply in South Asia despite economic growth in India; and (C) variations in sugar supply in Latin America.

Different trends in food supply changes were observed in South Asia and Latin America. In South Asia, we observed that India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and other countries of the region remained relatively stable in their consumption of all major food categories, as shown in Figure 5. In Latin America, countries also remained relatively stable in most food categories, except for a marked increase in sugar supply. The increase in sugar consumption was noted in all countries except Peru (Figure 5). Peru was also an exception from its neighbors for having maintained low dairy supplies and for having increased its fruit and vegetable supply.

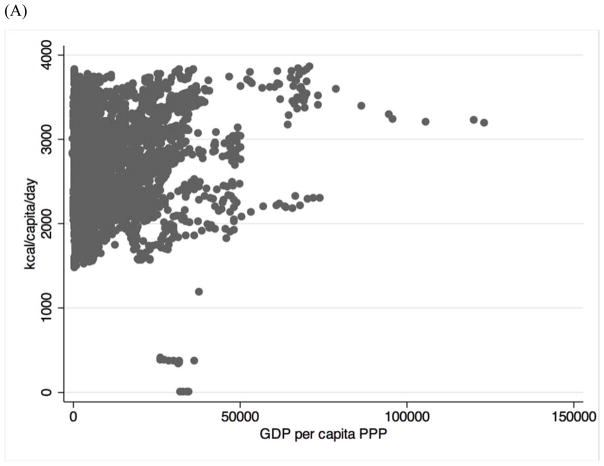

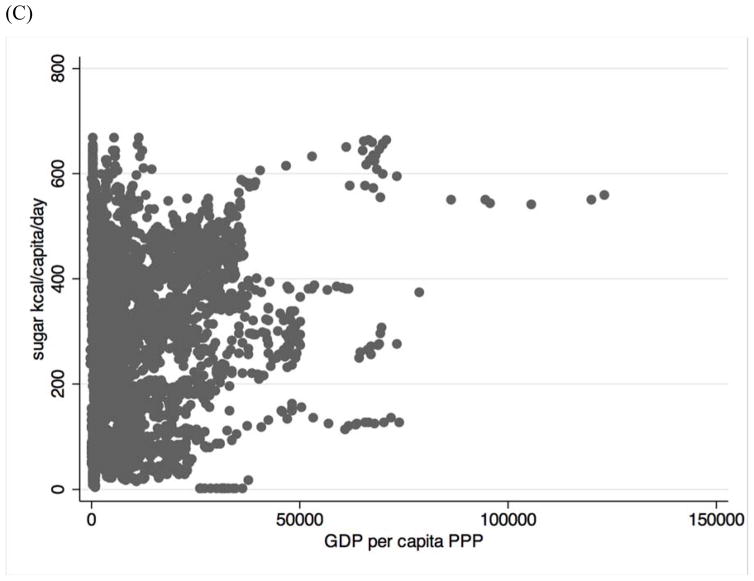

These differences in food supply trends were not explained by changes in GDP. As shown in Figure 6, GDP failed to explain a large portion of the variation in food supply among countries (R2<10%). Similarly, we observed that trends in food supply were not well explained by food importation. Food supply was more poorly explained by food importation than by GDP, as shown in Table 2. Looking further into the sources of food supply changes, we observed that most of the changes were associated with domestic food production, including domestic production of internationally-franchised products, as explored in more detail in the next section.

Figure 6.

Variations in food supply versus GDP: (A) total supply; (B) meat supply; (C) sugar supply; (D) vegetable supply; (E) edible oil supply.

Table 2.

GDP (per capita purchasing power parity in constant $US) and food imports ($US) versus food supply (expressed in kcals/capita/day). N=216 countries, 1961–2007.

| Food group | Versus GDP | R2 | Versus food imports | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cereals | −0.0010** | 0.001 | −3.6e-10 | 0.000 |

| Sugars | 0.0022*** | 0.033 | 2.7e-9*** | 0.015 |

| Meats | 0.0023*** | 0.038 | 3.1e-9*** | 0.021 |

| Dairy | 0.0019*** | 0.037 | 9.7e-10*** | 0.003 |

| Fruits | −0.00030*** | 0.003 | −1.7e-10 | 0.000 |

| Vegetables | 0.00025*** | 0.008 | 2.6e-10*** | 0.003 |

| Fats/oils | −0.00047*** | 0.005 | −1.6e-11 | 0.000 |

| Fish | −0.0000012 | 0.000 | 2.9e-10*** | 0.003 |

| Total kcals | 0.0077*** | 0.034 | 8.7e-9*** | 0.011 |

95% confidence intervals in brackets

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001

Trends in Big Food sales

Data from the food industry provide insights into how changes in food production and distribution are associated with overall changes in food supply. Data from the food industry are expressed in terms of changes in sales of products over time, clustered into two broad groups: beverage sales and packaged food sales.

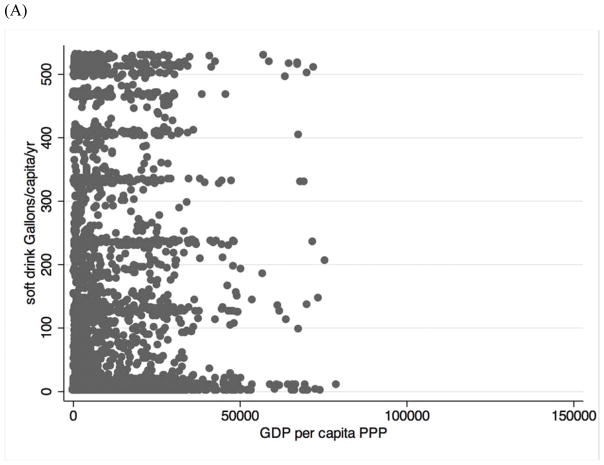

Data from beverage sales reveal that beverages are an increasing source of sugar supply to populations worldwide. As shown in Figure 7, soda sales (sales of non-diet sugar-sweetened carbonated beverages) have increased from 9.4 to 11.2 gallons per capita per year worldwide from 1997 to 2010. But as shown in Table 3, soda sales have been highly divergent between countries and regions. While soda sales are widely known to be high in North America and Latin America, the greatest increase in sales over the studied period actually occurred in Eastern Europe and the Middle East, where many countries experienced over a 200 gallon per capita per year increase in sales from 1997 to 2010 (Table 2). Soda sales are also not universally high or increasing across Latin American countries, either. While soda sales were high in Mexico (averaging 521 gallons/capita/year) and Argentina (477 gallons/capita/year), for example, they remained substantially lower in Peru (48 gallons), Uruguay (44 gallons), Ecuador (56 gallons), and Colombia (55 gallons). Similarly, while soda sales were high in the United States (250 gallons/capita/year), they remained substantially lower in Canada (140 gallons).

Figure 7.

Soft drink sales worldwide.

Table 3.

Countries experiencing the largest increase in carbonated non-diet soda and fruit/vegetable juice sales per capita per year, 1997–2010.

| Country | Change in gallons/capita/year, 1997–2010 | |

|---|---|---|

| Soda | ||

| Costa Rica | 501 | |

| Greece | 501 | |

| Kazakhstan | 373 | |

| Ukraine | 338 | |

| Georgia | 314 | |

| Juice | ||

| Germany | 478 | |

| Russia | 387 | |

| Serbia | 373 | |

| Peru | 323 | |

| Bulgaria | 321 |

In parallel to the increase in soda sales, juices (from fruits and vegetables) increased in sales worldwide (Figure 7), with the largest increases observed again in Eastern Europe, the Middle East and Latin America. While Peru maintained among the lowest levels of soda sales, it experienced among the highest increases in juice sales (323 gallons/capita/year). Similarly, Belarus decreased its soda sales by 290 gallons/capita/year from 1997 to 2010, while increasing its juice sales by 224 gallons/capita/year (see Table 3).

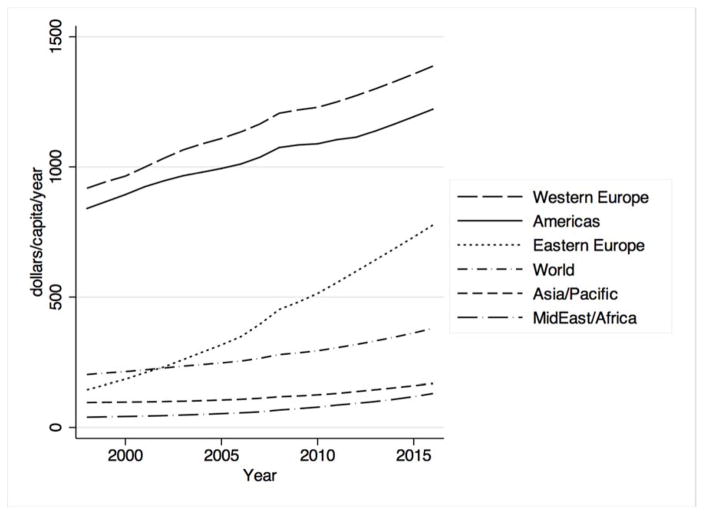

Data from processed food sales revealed similar increases in consumption in Eastern Europe and the Middle East. Most packaged food sales involved baked items (e.g., breads), dairy items (e.g., yogurts), confectionaries, and chilled processed foods (e.g., ready-to-eat meals). While packaged food sales were historically highest in Western Europe and North America, they increased in consumption most rapidly during the past decade in Eastern Europe, as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Packaged food sales worldwide.

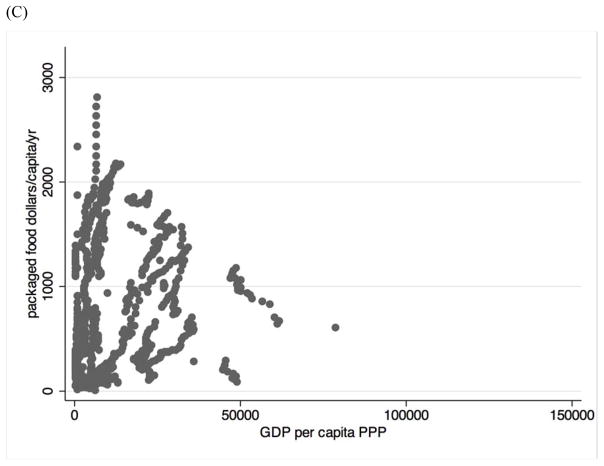

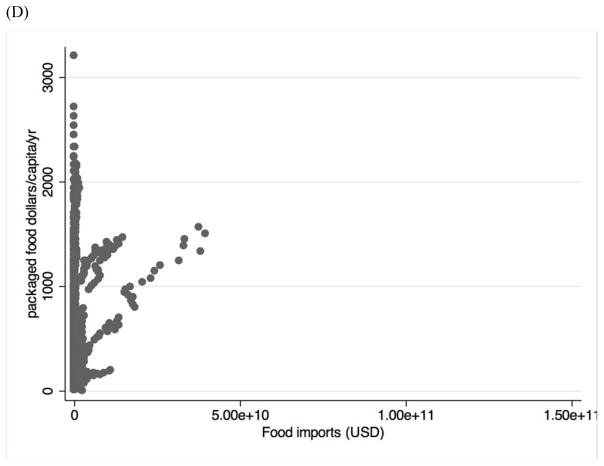

As with data on overall food supply, the data on beverage sales and packaged food sales was not well explained by GDP or by food imports (Figure 9). At similar levels of GDP and of food importation, countries differed greatly in how much beverage and packaged food sales occurred, suggesting other factors may be critical for explaining international differences in sales trends.

Figure 9.

Variations on food sales versus GDP and food imports. Soft drink sales versus (A) GDP and (B) food imports. Processed foods sales versus (A) GDP and (B) food imports.

Data from the food industry did reveal which companies were prominent in generating the majority of beverage and packaged food sales. These data reveal that the largest companies responsible for beverage and packaged food sales are multinational corporations who do not import most of their products to the affected countries, but often franchise local production. In terms of beverage sales, Table 4 reveals that the greatest sales worldwide are from Coca-Cola, followed by PepsiCo and Danone. We found little regional variation in which companies dominate beverage sales. In terms of packaged food sales, Table 4 also reveals that the greatest sales worldwide are from Nestle, followed by Kraft and Unilever. The distribution of market share among different regions is more varied in packaged food sales than in beverage sales, with the regional company Grupo Bimbo having a larger role in Latin America, but large North American multinationals otherwise dominating the landscape.

Table 4.

Top companies in terms of market share (total sales volume) worldwide in soft drinks and packaged foods, 1997–2010.

| Company | Volume of sales | % of global market share |

|---|---|---|

| Soft drinks | (mn of liters) | |

| Coca-Cola Co, The | 104,379.1 | 37.1% |

| PepsiCo Inc | 48,662.0 | 17.3% |

| Danone, Groupe | 21,838.5 | 7.8% |

| Nestlé SA | 18,741.9 | 6.7% |

| Tingyi (Cayman Islands) Holdings Corp | 8,020.9 | 2.9% |

| Dr Pepper Snapple Group Inc | 7,471.6 | 2.7% |

| Suntory Holdings Ltd | 4,884.1 | 1.7% |

| Hangzhou Wahaha Group | 3,986.4 | 1.4% |

| Aje Group | 2,870.1 | 1.0% |

| Uni-President Enterprises Corp | 2,635.2 | 0.9% |

| Packaged foods | ($US millions) | |

| Nestlé SA | 65,420.2 | 10.3% |

| Kraft Foods Inc | 62,354.4 | 9.8% |

| Unilever Group | 39,366.6 | 6.2% |

| PepsiCo Inc | 36,347.6 | 5.7% |

| Mars Inc | 28,470.5 | 4.5% |

| Danone, Groupe | 28,084.9 | 4.4% |

| Kellogg Co | 16,059.0 | 2.5% |

| General Mills Inc | 12,598.3 | 2.0% |

| Ferrero Group | 10,824.2 | 1.7% |

| Grupo Bimbo SAB de CV | 10,591.5 | 1.7% |

Discussion

Changes to the food supply across the world have been a source of increasing concern, as these food supply changes are thought to have a profound influence on the risk of chronic disease. Using data on food supply and food sales, we examined the extent to which the nutrition transition has been consistent or divergent between various regions and countries.

We observed several trends that contribute significant new knowledge to the existing literature. First, while it is well known that meat supply has been increasing (Popkin, 2006), our analysis clarified that much of this supply is concentrated in China (particularly in the form of pig meat) but is not necessarily inevitable in the context of economic development contrary to prior hypotheses (Speedy, 2003); India and other rapidly-developing countries in Latin America, Africa and other parts of Asia do not appear to be following China in their meat consumption. Meat consumption has also been driven by developed countries as well as low- and middle-income nations, for example by the substantial rise in poultry consumption in North America. Second, our analysis revealed that the nutrition transition does not merely involve an adoption of “Western” diets universally, but can also include an increase in the supply of edible oils that are uncommon in Western countries. The increased supply of foods uncommon in Western diets includes the increasing supply of palm oil in Southeast Asia and Latin America. The increasing supply of palm oil has been linked to cardiovascular disease (Chen, Seligman, Farquhar, & Goldhaber-Fiebert, 2011; Vega-Lopez, Ausman, Jalbert, Erkkila, & Lichtenstein, 2006). Third, our analysis revealed that large inter-regional differences exist between otherwise similar neighboring countries, even as entire regions undergo rapid economic development. For example, large inter-regional differences in Latin America reveal that the country of Peru has avoided the increases in sugar and dairy supply that some of its neighbors have experienced. This calls for further historical analysis into what factors may be contributing to Peru’s divergence from other countries in the region, even when Peru has signed similar trade agreements and has experienced similar economic development as its neighbors (Organization of American States, 2014). Disaggregating the FAO data by total supply versus imported supply alone would be important to regress against emerging data on trade liberalization by country, once such data are further standardized for analysis. Finally, we observed that while beverages and processed foods have generally increased in sales around the world, there is substantial variation in sales among countries, and the sales are not concentrated only in North America and Latin America, but also increasing in Eastern Europe and the Middle East, where less attention has been paid to their health implications.

Our findings provide several insights for future research endeavors. The divergence between otherwise similar countries provides a “natural experiment” to investigate what domestic policies could be responsible for variations in food supply between countries. Understanding reasons for the divergence of Peru, for example, or the reasons why India and China diverge in even non-beef consumption (not religiously-related meat consumption) could help determine which agriculture, trade, and nutrition policies are associated with food supply changes that may be responsible for improvements or decrements in human health. We found that large variations in food supply and sales cannot be explained by rising income or food importation alone. We also found that much of the increase in food supply and sales appears related to domestic production, including production from franchises of large multinational corporations. Hence, identifying how food supply and sales could be altered to improve public health will require further analysis of domestic variations in food policy, not just analyses of overall household income or international trade agreements. Such variations in domestic production policy could be added to international chronic disease policy monitoring databases that are in their early stages of data collection, such as the World Health Organization’s chronic disease policy database (David Stuckler & Basu, 2013; World Health Organization, 2014).

Our findings are limited, however, by caveats associated with the data used here. The findings are based on food supply and food sales, and hence are not as accurate proxies for actual food consumption as 24-hour dietary recalls or other direct dietary assessments, which are generally unavailable outside of North America and Europe. Food supply and food sales will tend to overestimate consumption where there is significant food wastages, as in the United States (Hall, Guo, Dore, & Chow, 2009). The findings also rely on data derived from formal food sales rather than informal bartering systems, and hence do not capture the complex dynamics of food supply in many lower-income countries. Finally, our between-country analyses do not account for complex within-country dynamics, which require more dedicated databases to study inequalities that are increasing in rapidly-developing countries such as India.

As policy proposals to alter food supply continue to be proposed in an effort to address the global rise in chronic disease (Sanjay Basu et al., 2014; Sanjay Basu, Babiarz, et al., 2013), our analyses are a reminder that longitudinal trends in food supply have markedly diverged between nations, even among countries facing relatively similar socioeconomic changes. Further efforts are required to understand what explains this divergence even as we seek to address the health consequences of changing agricultural systems and changing diets worldwide.

References

- Basu S, Babiarz KS, Ebrahim S, Vellakkal S, Stuckler D, Goldhaber-Fiebert JD. Palm oil taxes and cardiovascular disease mortality in India: economic-epidemiologic model. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed) 2013;347:f6048. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f6048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu S, Stuckler D, McKee M, Galea G. Nutritional determinants of worldwide diabetes: an econometric study of food markets and diabetes prevalence in 173 countries. Public Health Nutrition. 2012;1(1):1–8. doi: 10.1017/S1368980012002881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu S, Vellakkal S, Agrawal S, Stuckler D, Popkin B, Ebrahim S. Averting Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes in India through Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Taxation: An Economic-Epidemiologic Modeling Study. PLoS Medicine. 2014;11(1):e1001582. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu S, Yoffe P, Hills N, Lustig RH. The relationship of sugar to population-level diabetes prevalence: an econometric analysis of repeated cross-sectional data. PloS One. 2013;8(2):e57873. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen BK, Seligman B, Farquhar JW, Goldhaber-Fiebert JD. Multi-Country analysis of palm oil consumption and cardiovascular disease mortality for countries at different stages of economic development: 1980–1997. Globalization and Health. 2011;7:1–10. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-7-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drewnowski A, Popkin BM. The nutrition transition: new trends in the global diet. Nutrition Reviews. 1997;55(2):31–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1997.tb01593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Euromonitor International. Passport Global Market Information Database. New York: Euromonitor; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agricultural Organization. FAOSTAT database. Rome: United Nations; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hall KD, Guo J, Dore M, Chow CC. The Progressive Increase of Food Waste in America and Its Environmental Impact. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(11):e7940. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organization of American States. Foreign Trade Information System - Trade Agreements in Force. Washington D.C: OAS; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Popkin BM. The nutrition transition in low-income countries: an emerging crisis. Nutrition Reviews. 1994;52(9):285–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1994.tb01460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popkin BM. The nutrition transition and obesity in the developing world. The Journal of Nutrition. 2001;131(3):871S–873S. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.3.871S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popkin BM. Global nutrition dynamics: the world is shifting rapidly toward a diet linked with noncommunicable diseases. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2006;84(2):289–298. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.1.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy KS, Yusuf S. Emerging epidemic of cardiovascular disease in developing countries. Circulation. 1998;97(6):596–601. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.6.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speedy AW. Global Production and Consumption of Animal Source Foods. The Journal of Nutrition. 2003;133(11):4048S–4053S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.11.4048S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuckler D, Basu S. Malignant Neglect: The Failure to Address the Need to Prevent Premature Non-communicable Disease Morbidity and Mortality. PLoS Medicine. 2013;10(6):e1001466. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuckler D, McKee M, Ebrahim S, Basu S. Manufacturing epidemics: the role of global producers in increased consumption of unhealthy commodities including processed foods, alcohol, and tobacco. PLoS Medicine. 2012;9(6):e1001235. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega-Lopez S, Ausman LM, Jalbert SM, Erkkila AT, Lichtenstein AH. Palm and partially hydrogenated soybean oils adversely alter lipoprotein profiles compared with soybean and canola oils in moderately hyperlipidemic subjects. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2006;84:54–62. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. World Development Indicators. Washington D.C: IBRD; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Nutrition, Obesity, and Physical Activity Database. Geneva: WHO; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Yang W, Lu J, Weng J, Jia W, Ji L, Xiao J, … He J. Prevalence of Diabetes among Men and Women in China. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;362(12):1090–1101. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf S, Reddy S, Ôunpuu S, Anand S. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases part I: general considerations, the epidemiologic transition, risk factors, and impact of urbanization. Circulation. 2001;104(22):2746–2753. doi: 10.1161/hc4601.099487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]