Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Qualitative studies have suggested that food insecurity adversely affects infant feeding practices. We aimed to determine how household food insecurity relates to breastfeeding initiation, duration of exclusive breastfeeding and vitamin D supplementation of breastfed infants in Canada.

METHODS:

We studied 10 450 women who had completed the Maternal Experiences — Breastfeeding Module and the Household Food Security Survey Module of the Canadian Community Health Survey (2005–2014) and who had given birth in the year of or year before their interview. We used multivariable Cox proportional hazards models and logistic regression to examine the relation between food insecurity and infant feeding practices, adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics, maternal mood disorders and diabetes mellitus.

RESULTS:

Overall, 17% of the women reported household food insecurity, of whom 8.6% had moderate food insecurity and 2.9% had severe food insecurity (weighted percentages). After adjustment for sociodemographic factors, women with food insecurity were no less likely than others to initiate breastfeeding or provide vitamin D supplementation to their infants. Half of the women with food insecurity ceased exclusive breastfeeding by 2 months, whereas most of those with food security persisted with breastfeeding for 4 months or more. Relative to women with food security, those with marginal, moderate and severe food insecurity had significantly lower odds of exclusive breastfeeding to 4 months, but only women with moderate food insecurity had lower odds of exclusive breastfeeding to 6 months, independent of sociodemographic characteristics (odds ratio 0.60, 95% confidence interval 0.39–0.92). Adjustment for maternal mood disorder or diabetes slightly attenuated these relationships.

INTERPRETATION:

Mothers caring for infants in food-insecure households attempted to follow infant feeding recommendations, but were less able than women with food security to sustain exclusive breastfeeding. Our findings highlight the need for more effective interventions to support food-insecure families with newborns.

Household food insecurity — defined as inadequate or insecure access to food because of financial constraints — is a serious public health problem in affluent western countries,1–3 and it disproportionately affects households with children.1,2 In Canada, household food insecurity has been linked to myriad physical and mental health problems,4–8 to poorer chronic disease management9,10 and to heightened nutritional vulnerability among adults and children,11 but its impact on infant nutrition is less clear. Because breastfeeding offers a secure, low-cost, optimal food supply for infants, Canadian health policy and public health programs promote it as a key strategy to protect vulnerable infants from food insecurity.12–15 However, there is some question as to the extent to which women struggling with food insecurity can follow breastfeeding recommendations.14

Adherence to current breastfeeding recommendations is poor in Canada,16 particularly among socially and economically vulnerable women,17,18 but the effects of household food insecurity on breastfeeding rates have not been examined. Qualitative studies have suggested that food insecurity contributes to the early cessation of breastfeeding,14,19 and a 1998–2002 Quebec study suggested that breastfeeding to 4 months was less common among infants in food-insufficient than food-sufficient families, although the difference was not statistically significant.20 Studying the effects of household food insecurity on infant feeding is complicated by the fact that women in food-insecure households are more likely to experience depression and diabetes mellitus,7,21,22 conditions that have been found to affect breastfeeding initiation and duration negatively.23,24

Drawing on data from the Canadian Community Health Survey, we aimed to determine how household food insecurity status relates to breastfeeding initiation, duration of exclusive breastfeeding, exclusive breastfeeding to 4 months, and adherence to recommendations for exclusive breastfeeding to 6 months and for supplementation of breastfed infants with vitamin D.

Methods

Survey and sample

The Canadian Community Health Survey is a population-representative survey of about 130 000 individuals 12 years or older per cycle. Since 2005, it has included assessment of household food insecurity over the past 12 months using the Household Food Security Survey Module.25 Information about recent births and infant feeding practices is captured using the Maternal Experiences — Breastfeeding Module,26 which is administered to female respondents 15 to 55 years of age who report having given birth in the previous 5 years. The module collects data on breastfeeding initiation and duration and on vitamin supplementation of the respondent and her infant. However, neither of these 2 modules has been administered in all provinces and territories in every cycle of the Canadian Community Health Survey.

To maximize the sample size, we pooled data from the 2005, 2007/08, 2009/10, 2011/12 and 2013/14 survey cycles. The Household Food Security Survey Module was optional in 2005, 2009/10 and 2013/14, and the Maternal Experiences — Breastfeeding Module was optional in 2013/14, meaning that the administration of these modules was at the discretion of the province or territory (for a list of the provinces and territories with both modules, by survey cycle, see Appendix 1, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.170880/-/DC1). We included only respondents to whom both modules were administered, and we restricted our sample to women who reported having given birth in the year of or the year before the interview, to obtain relatively concurrent data on household food security and infant feeding behaviours. Household income was imputed by Statistics Canada for all participants with missing data (about 30% of the sample). We excluded respondents with missing values for any other variable used in our analyses.

Measures

We determined household food insecurity status from the number of affirmative responses to the 18 questions in the Household Food Security Survey Module (listed in Appendix 2, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.170880/-/DC1). We applied Health Canada’s coding method (Appendix 3, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.170880/-/DC1) to define moderate and severe household food insecurity.25 Women with 1 affirmative response were classified as having marginal food insecurity, and those with no affirmative responses were considered to have food security.

Breastfeeding initiation was indicated by an affirmative response to the question, “Did you breastfeed or try to breastfeed your baby, even if only for a short time?” Duration of exclusive breastfeeding was determined by the age of the infant when non-breastmilk liquids or solids were first introduced. The survey explicitly refers to the mother’s experience with her last baby.

The presence of mood disorders and diabetes was reported on the basis of diagnosis by a health professional and the condition having lasted or being expected to last for 6 months or more. Mood disorders included depression, bipolar disorder, mania and dysthymia. Diabetes included type 1, type 2 and gestational diabetes.

Statistical analysis

We used multivariable logistic regression to examine the relation between household food insecurity status and breastfeeding initiation, adjusting for the following maternal and household sociodemographic characteristics, previously identified as being associated with food insecurity and infant feeding practices in Canada:7,16,17,27 maternal age, presence of a partner, maternal education, maternal immigration status (defined in terms of citizenship at birth), Aboriginal status, number of children in the household and household income (converted to 2014 constant dollars using the Consumer Price Index and adjusted for family size by dividing by the square root of household size). We also adjusted for survey year to account for variation in the composition of our sample across survey cycles (as detailed in Appendix 1) and possible secular trends in infant feeding practices. Because women in food-insecure households are more likely to suffer from depression and diabetes,7,21,22 and because these conditions negatively affect breastfeeding initiation and duration,23,24 binary variables denoting the presence of mood disorders or diabetes were added to the adjusted model to control for potential confounding factors associated with women’s health status.

To examine the relation between duration of exclusive breastfeeding up to 6 months and household food insecurity status, we ran a series of 4 Cox proportional hazards models on the subgroup of women who initiated breastfeeding but reported having ceased exclusive breastfeeding by the time of the Canadian Community Health Survey interview. These models provided estimates (hazard ratios [HRs]) of early exclusive breastfeeding cessation rates for women by food insecurity status. Following the computation of unadjusted hazard ratios, we re-ran the model including survey year and the sociodemographic covariables described above, and then adding binary variables denoting the presence of a mood disorder or diabetes.

We explored the relation between household food insecurity status and the continuation of any breastfeeding after early cessation of exclusive breastfeeding (defined here as cessation before 6 mo) among the subset of women who began breastfeeding but ceased exclusive breastfeeding before 6 months. We examined mean duration of continued breastfeeding using logistic regression with contrasts to compare women with food security and women with marginal, moderate or severe food insecurity.

Within the subgroup of women who initiated breastfeeding, we used multivariable logistic regression analyses to examine the relation between household food insecurity status and the odds of women reaching 4 or 6 months of exclusive breastfeeding and following recommendations for vitamin D supplementation.28 We adjusted these models for survey year and the sociodemographic covariables described above and then re-ran them including binary variables denoting the presence of a mood disorder or diabetes. Information on vitamin D supplementation was available for the subgroup of women who breastfed for at least 1 week. The duration of exclusive breastfeeding was also assessed in relation to thresholds of 4 and 6 months. Six months is the current global recommendation,28 although infants may be fed complementary foods earlier than 6 months if they show signs of readiness;28 the introduction of complementary foods before 4 months is potentially detrimental to infant health.29

As a sensitivity analysis to examine how the exclusion of women with missing data for sociodemographic variables affected our results, we re-ran all of the unadjusted models with these women included in the sample.

We conducted all analyses with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute). To account for the complex survey design, we used proc survey commands with bootstrap replications (n = 500) and bootstrap weights provided by Statistics Canada. In keeping with Statistics Canada’s disclosure policies for analyses of survey microdata in the Research Data Centres, we report here the rounded, unweighted sample size, but weighted prevalence and parameter estimates.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the research ethics board of the University of Toronto.

Results

The original sample was about 10 550 women (rounded); of these, about 100 women (rounded) were excluded because of missing data (mostly for the education and Aboriginal identity variables). Our final sample was 10 450 women (rounded). The sociodemographic characteristics of the study sample and prevalence of mood disorders and diabetes are presented in Table 1. Seventeen percent of women were living in food-insecure households: 5.5% with marginal food insecurity, 8.6% with moderate food insecurity and 2.9% with severe food insecurity (Table 1).

Table 1:

Sociodemographic and maternal health characteristics of the study sample, by household food insecurity status (based on Canadian Community Health Surveys, 2005–2014; rounded n = 10 450)*

| Characteristic | Food security status; % of respondents† | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any status | Secure | Marginally insecure | Moderately insecure | Severely insecure | |

| Weighted prevalence | 100 | 83.0 | 5.5 | 8.6 | 2.9 |

| Age, yr, mean ± SEM | 30.5 ± 0.2 | 30.8 ± 0.1 | 29.5 ± 0.5 | 28.8 ± 0.7 | 28.9 ± 1.4 |

| Education | |||||

| Postsecondary graduation | 71.5 | 75.9 | 58.1 | 48.6 | 40.2 |

| Less than postsecondary graduation | 28.5 | 24.1 | 41.9 | 51.4 | 59.8 |

| Partnership status | |||||

| Married or common-law | 88.8 | 92.3 | 78.7 | 72.5 | 56.4 |

| Single, divorced, separated, widowed | 11.2 | 7.7 | 21.3 | 27.5 | 43.6 |

| Immigrant status‡ | |||||

| Non-immigrant | 73.3 | 74.2 | 69.3 | 67.4 | 72.6 |

| Immigrant | 26.7 | 25.8 | 30.7 | 32.6 | 27.4 |

| No. of children < 18 yr, mean ± SEM | 1.7 ± 0.03 | 1.7 ± 0.04 | 1.9 ± 0.07 | 2.0 ± 0.09 | 2.0 ± 0.08 |

| Income (adjusted for household size),§ $, mean ± SEM | 44 050 ± 966 | 48 480 ± 800 | 28 000 ± 1775 | 20 600 ± 1802 | 17 080 ± 1629 |

| Aboriginal identity | |||||

| No | 95.3 | 96.4 | 92.2 | 89.4 | 85.7 |

| Yes | 4.8 | 3.6 | 7.8 | 10.6 | 14.3 |

| Mood disorder | |||||

| No | 93.3 | 95.3 | 88.5 | 83.3 | 75.7 |

| Yes | 6.7 | 4.7 | 11.5 | 16.7 | 24.3 |

| Diabetes mellitus | |||||

| No | 98.6 | 98.9 | 96.2 | 98.2 | 97.1 |

| Yes | 1.4 | 1.1 | 3.8 | 1.9 | 2.9 |

Note: SEM = standard error of the mean.

In keeping with Statistics Canada’s disclosure policies for analyses of survey microdata, only weighted prevalence and parameter estimates are reported in this table.

Except where indicated otherwise.

Immigrant status defined by Canadian citizenship at birth.

Before-tax household income converted to 2014 constant dollars using the Consumer Price Index and adjusted for family size by dividing by the square root of household size.

Most women initiated breastfeeding: 91.6% of those with food security, 88.8% of those with marginal food insecurity, 83.3% of those with moderate food insecurity and 86.0% of those with severe food insecurity. Once sociodemographic characteristics were taken into account, breastfeeding initiation was unrelated to household food insecurity status (Appendix 4, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.170880/-/DC1).

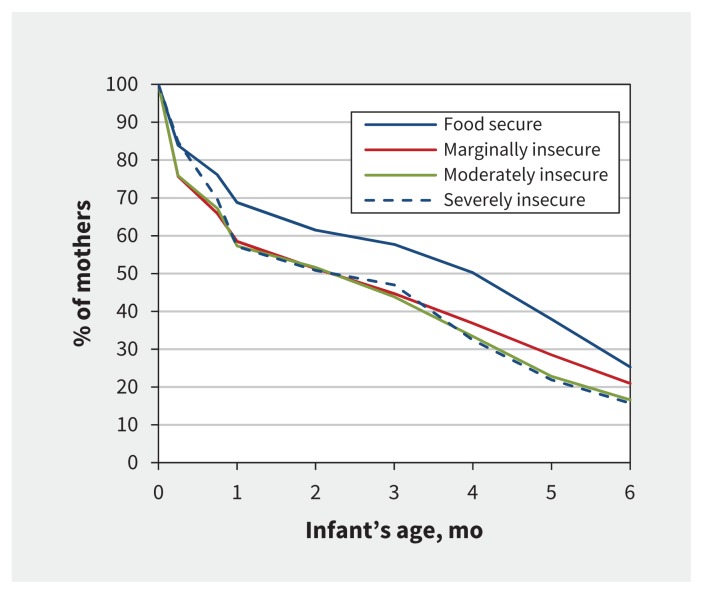

Among women who initiated breastfeeding (rounded n = 7950), the duration of exclusive breastfeeding differed markedly by household food insecurity status. Irrespective of the severity of food insecurity, almost half of women with food insecurity had ceased exclusive breastfeeding by 2 months, whereas half of women with food security exclusively breastfed to at least 4 months (Figure 1). In the unadjusted model, exclusive breastfeeding appeared to be negatively affected by all 3 levels of food insecurity. After adjustment for sociodemographic characteristics, only the relation with moderate food insecurity remained significant (HR 1.26, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.06–1.48); the hazard ratios for marginal food insecurity and severe food insecurity were HR 1.18 (95% CI 0.99–1.39) and HR 1.21 (95% CI 0.97–1.52), respectively (Table 2). When the presence of a mood disorder or diabetes was taken into account, severe food insecurity lost marginal significance (HR 1.20, 95% CI 0.96–1.50 and HR 1.19, 95% CI 0.96–1.49 for mood disorder or diabetes, respectively).

Figure 1:

Proportion of women exclusively breastfeeding during the first 6 months, by food insecurity status. Rounded n = 7950.

Table 2:

Risk of early (< 6 mo) cessation of exclusive breastfeeding in relation to household food insecurity status, sociodemographic characteristics, and mother’s mood disorder or diabetes mellitus*

| Variable | Model; HR (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Model 1† | Model 2‡ | Model 3§ | |

| Household food insecurity status | ||||

| Secure | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Marginally insecure | 1.21 (1.02–1.42) | 1.18 (0.99–1.39) | 1.17 (0.98–1.39) | 1.17 (0.99–1.38) |

| Moderately insecure | 1.29 (1.13–1.46) | 1.26 (1.06–1.48) | 1.25 (1.05–1.47) | 1.24 (1.05–1.46) |

| Severely insecure | 1.29 (1.08–1.55) | 1.21 (0.97–1.52) | 1.20 (0.96–1.50) | 1.19 (0.96–1.49) |

| Age, per yr | NA | 0.99 (0.98–1.00) | 0.99 (0.98–1.00) | 0.99 (0.98–1.00) |

| Education | ||||

| Postsecondary graduation | NA | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Less than postsecondary graduation | NA | 1.07 (0.98–1.18) | 1.08 (0.98–1.18) | 1.07 (0.98–1.18) |

| Partnership status | ||||

| Married or common-law | NA | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Single, divorced, separated, widowed | NA | 1.08 (0.95–1.21) | 1.07 (0.95–1.21) | 1.07 (0.95–1.21) |

| Immigrant status | ||||

| Non-immigrant | NA | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Immigrant | NA | 0.91 (0.84–1.00) | 0.92 (0.84–1.00) | 0.91 (0.84–1.00) |

| No. of children < 18 yr, per child | NA | 0.91 (0.88–0.95) | 0.91 (0.88–0.95) | 0.91 (0.88–0.95) |

| Income (adjusted for household size), per $5000 | NA | 1.00 (1.00–1.01) | 1.00 (1.00–1.01) | 1.00 (1.00–1.01) |

| Aboriginal identity | ||||

| No | NA | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Yes | NA | 0.96 (0.84–1.08) | 0.96 (0.84–1.09) | 0.95 (0.84–1.08) |

| Mood disorder | ||||

| No | NA | NA | 1.00 (ref) | NA |

| Yes | NA | NA | 1.11 (0.96–1.27) | NA |

| Diabetes mellitus | ||||

| No | NA | NA | NA | 1.00 (ref) |

| Yes | NA | NA | NA | 1.80 (1.09–2.96) |

| Survey year | ||||

| 2005 | NA | 1.09 (0.97–1.21) | 1.09 (0.98–1.21) | 1.08 (0.97–1.21) |

| 2007 | NA | 1.16 (1.02–1.32) | 1.16 (1.02–1.32) | 1.17 (1.03–1.33) |

| 2008 | NA | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| 2009 | NA | 1.16 (1.01–1.32) | 1.16 (1.02–1.32) | 1.16 (1.02–1.32) |

| 2010 | NA | 1.04 (0.92–1.18) | 1.04 (0.92–1.18) | 1.04 (0.91–1.18) |

| 2011 | NA | 1.13 (1.00–1.29) | 1.13 (1.00–1.29) | 1.13 (0.99–1.28) |

| 2012 | NA | 1.21 (1.06–1.37) | 1.21 (1.06–1.38) | 1.21 (1.07–1.38) |

| 2013 | NA | 1.21 (1.06–1.39) | 1.21 (1.06–1.38) | 1.21 (1.06–1.39) |

| 2014 | NA | 1.06 (0.92–1.23) | 1.06 (0.91–1.23) | 1.07 (0.92–1.23) |

Note: CI = confidence interval, HR = hazard ratio, NA = not applicable, ref = reference category.

Rounded n = 7950.

Adjusted for age, education, partnership status, immigrant status, number of children < 18 years of age, income (adjusted for household size), Aboriginal identity and survey year.

Adjusted for the same variables as model 1, plus adjustment for presence of mood disorder.

Adjusted for the same variables as model 1, plus adjustment for presence of diabetes mellitus.

Of women who stopped exclusive breastfeeding before 6 months (rounded n = 4300), 45.3% of those with food security, 36.3% of those with marginal food insecurity, 41.3% of those with moderate food insecurity and 35.0% of those with severe food insecurity continued to breastfeed their infant for at least 1 month. These rates were not significantly different (p = 0.3). There was no significant difference in the mean duration of continued breastfeeding between mothers with food security (1.7 mo) and those with marginal (1.5 mo; p = 0.7) or moderate (1.4; p = 0.2) food insecurity, but mothers with severe food insecurity continued to breastfeed for a significantly shorter time (1.2 mo; p = 0.04) than mothers with food security.

Independent of sociodemographic characteristics, the odds of exclusive breastfeeding to 4 months were lower among women with any level of food insecurity compared with women who had food security, but only women in moderately food-insecure households had significantly lower odds of reaching the recommended 6 months of exclusive breastfeeding (odds ratio 0.60, 95% CI 0.39–0.92) (Table 3). There was no relation between household food insecurity status and a mother’s odds of providing her baby with vitamin D supplementation once sociodemographic characteristics were taken into account. The presence of a mood disorder or diabetes did not significantly alter these relations. The inclusion of missing respondents in the unadjusted models did not alter the observed associations between household food insecurity status and any of the outcomes (data not shown).

Table 3:

Odds of infant feeding practices in relation to household food insecurity status, sociodemographic characteristics, and mother’s mood disorder and diabetes mellitus

| Variable | % of mothers | Model; OR (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Model 1‡ | Model 2§ | Model 3¶ | ||

| Exclusively breastfed to ≥ 4 mo* | |||||

| Food security | 50.0 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Marginal food insecurity | 36.6 | 0.58 (0.41–0.81) | 0.62 (0.42–0.90) | 0.63 (0.43–0.93) | 0.64 (0.44–0.92) |

| Moderate food insecurity | 33.5 | 0.50 (0.38–0.66) | 0.57 (0.40–0.80) | 0.60 (0.42–0.85) | 0.57 (0.40–0.82) |

| Severe food insecurity | 32.4 | 0.48 (0.31–0.74) | 0.61 (0.38–0.99) | 0.65 (0.40–1.05) | 0.62 (0.39–1.01) |

| Exclusively breastfed to ≥ 6 mo* | |||||

| Food security | 25.1 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Marginal food insecurity | 20.7 | 0.78 (0.53–1.16) | 0.78 (0.50–1.21) | 0.78 (0.50–1.22) | 0.80 (0.52–1.22) |

| Moderate food insecurity | 16.7 | 0.60 (0.43–0.83) | 0.60 (0.39–0.92) | 0.61 (0.39–0.95) | 0.61 (0.40–0.93) |

| Severe food insecurity | 15.7 | 0.56 (0.31–1.01) | 0.59 (0.30–1.19) | 0.60 (0.29–1.22) | 0.60 (0.30–1.20) |

| Supplementation with vitamin D for baby† | |||||

| Food security | 80.0 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Marginal food insecurity | 73.7 | 0.70 (0.44–1.13) | 0.84 (0.47–1.51) | 0.84 (0.47–1.51) | 0.84 (0.46–1.53) |

| Moderate food insecurity | 73.1 | 0.68 (0.49–0.95) | 0.88 (0.63–1.24) | 0.89 (0.64–1.25) | 0.89 (0.63–1.24) |

| Severe food insecurity | 70.9 | 0.61 (0.34–1.09) | 0.84 (0.41–1.69) | 0.85 (0.42–1.69) | 0.84 (0.41–1.72) |

Note: CI = confidence interval, OR = odds ratio, ref = reference category.

Rounded n = 7950.

Rounded n = 8050.

Adjusted for age, education, partnership status, immigrant status, number of children < 18 years of age, income (adjusted for household size), Aboriginal identity and survey year.

Adjusted for the same variables as model 1, plus adjustment for presence of mood disorder.

Adjusted for the same variables as model 1, plus adjustment for presence of diabetes mellitus.

Interpretation

Most of the women in this study initiated breastfeeding and provided their infants with vitamin D supplementation, irrespective of their household food insecurity status, but food insecurity negatively affected the duration of exclusive breastfeeding. Although exclusive breastfeeding to 6 months was not the norm even among women in food-secure households, women with food insecurity ceased exclusive breastfeeding sooner than other women, and this effect was independent of other known influences on breastfeeding.

The earlier cessation of exclusive breastfeeding by women in food-insecure households means that their infants are less likely to reap the physical and emotional health benefits of breastfeeding, 29,30 and the women will not gain the risk reductions for obesity, type 2 diabetes, breast cancer and ovarian cancer that have been associated with breastfeeding.31 The cessation of exclusive breastfeeding is also problematic because it necessitates formula feeding, which creates a financial burden that food-insecure families can ill afford. Qualitative research has suggested that mothers in food-insecure circumstances struggle to maintain an adequate supply of formula, and the help available from food banks and other community agencies is often insufficient.14,19,32 Thus, the early cessation of breastfeeding for infants in food-insecure households may have further negative implications for infant nutrition.

Our study focused on the first 6 months of life, but insofar as households remain food insecure, infants in these settings are likely to experience other disadvantages. Longitudinal research from Quebec has shown that the exposure of toddlers to food insecurity increases their odds of persistent hyperactivity and inattention later in childhood,33 and nationally, children’s exposure to hunger has been found to predict poorer general health and the diagnosis of chronic health conditions (e.g., asthma, depression) several years later.34–36 Although we lack data on the duration of food insecurity for the families in this study, other Canadian research has suggested that household food insecurity, particularly severe food insecurity, is a persistent rather than a transient experience for most families.33,37

Our findings raise serious questions about the adequacy of existing supports for mothers vulnerable to food insecurity. There is some evidence that women with food insecurity who have high levels of participation in programs operated through the Canada Prenatal Nutrition Program38 are more likely to initiate and continue breastfeeding than less involved, food-insecure participants,39 but neither the proportion of women with food insecurity participating in these programs nor the effect of program participation on household food insecurity is known. The potential for income-based interventions to affect infant feeding practices positively is suggested by the significant increase in breastfeeding initiation observed among low-income women in Manitoba following a modest prenatal income supplement,40 but the supplement ended at birth and neither household food insecurity nor breastfeeding duration was assessed. Given the sensitivity of household food insecurity to improvements in income,41–43 programs providing income supplements to low-income pregnant women and new mothers (e.g., Newfoundland and Labrador’s Mother and Baby Nutrition Supplement and New Brunswick’s Pre/Postnatal Benefit Program) may be effective in reducing household food insecurity and may thereby support healthy infant feeding practices; however, program evaluations are needed for confirmation. It will also be important to evaluate the effects of the Canada Child Benefit, introduced in July 2016, on household food insecurity status and breastfeeding duration. The effectiveness of public health efforts to encourage breastfeeding as a food security strategy for infants may be contingent on the reduction of household food insecurity, but more research is needed to identify the most effective and efficient means of intervention.

Limitations

To maximize our sample of mothers with food insecurity, we pooled several population surveys, including some without comprehensive national data. Although there were no changes in infant feeding recommendations over this period, we charted some year-to-year variation in breastfeeding initiation and early cessation. Given variation in the composition of our sample by survey year, we cannot infer secular trends from these results. Additionally, the relatively small number of women with severe food insecurity in the sample limited our analyses of the effect of severity of household food insecurity on infant feeding practices. This study was also limited by the fact that the available measures of food insecurity, infant feeding behaviours and maternal health are not exactly concurrent. In the absence of data on the exact age of the most recently born child at the time of the woman’s interview, we included mothers in our sample if they gave birth in the year of or year before the survey interview. Thus, our sample must include women for whom the 12-month assessment of household food insecurity and measures of maternal mood disorders and diabetes did not overlap with the first 6 months of their infant’s life. To the extent that these sources of error influenced our analyses, they would bias our findings toward the null. We were also limited in our measure of adherence to recommendations for vitamin D supplementation, because we lacked data on supplementation frequency, duration and dose; this precluded assessment of women’s adherence to the 10 μg (400 IU) per day recommendation.28

Conclusion

The early cessation of exclusive breastfeeding among women in households with food insecurity highlights the need for more effective interventions to support vulnerable women with newborns and to address the underlying causes of food insecurity among Canadian families.

See related article at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/doi/10.1503/cmaj.180167

Footnotes

Visual abstract available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.170880/-/DC2

Competing interests: None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Sarah Orr and Valerie Tarasuk conceived of the study and its design. Sarah Orr conducted the statistical analyses with guidance from Valerie Tarasuk. All of the authors were responsible for interpretation of the study results. Sarah Orr, Naomi Dachner and Valerie Tarasuk drafted the manuscript, and all of the authors contributed to revising it critically for important intellectual content. All of the authors gave final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: This study was funded by a Programmatic Grant in Health and Health Equity from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) (FRN 115208). Sarah Orr was supported by a Post-Doctoral Fellowship Award from the CIHR (FRN 129818).

References

- 1.Coleman-Jensen A, Rabbitt M, Gregory C, et al. Household food insecurity in the United States in 2014. Econ Res Rep ERR-194. Washington: US Department of Agriculture; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tarasuk V, Mitchell A, Dachner N. Household food insecurity in Canada, 2014. Toronto: University of Toronto, Department of Nutritional Sciences, PROOF Food Insecurity Policy Research; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loopstra R, Reeves A, McKee M, et al. Food insecurity and social protection in Europe: quasi-natural experiment of Europe’s great recessions 2004–2012. Prev Med 2016;89:44–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Che J, Chen J. Food insecurity in Canadian households. Health Rep 2001; 12(4):11–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jessiman-Perreault G, McIntyre L. The household food insecurity gradient and potential reductions in adverse population mental health outcomes in Canadian adults. SSM Popul Health 2017;3:464–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muldoon KA, Duff PK, Fielden S, et al. Food insufficiency is associated with psychiatric morbidity in a nationally representative study of mental illness among food insecure Canadians. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2013;48:795–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loopstra R, Tarasuk V. What does increasing severity of food insecurity indicate for food insecure families? Relationship between severity of food insecurity and indicators of material hardship and constrained food purchasing. J Hunger Environ Nutr 2013;8:337–49. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vozoris NT, Tarasuk VS. Household food insufficiency is associated with poorer health. J Nutr 2003;133:120–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anema A, Chan K, Chen Y, et al. Relationship between food insecurity and mortality among HIV-positive injection drug users receiving antiretroviral therapy in British Columbia, Canada. PLoS One 2013;8:e61277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gucciardi E, Vogt JA, DeMelo M, et al. Exploration of the relationship between household food insecurity and diabetes care in Canada. Diabetes Care 2009; 32:2218–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirkpatrick SI, Tarasuk V. Food insecurity is associated with nutrient inadequacies among Canadian adults and adolescents. J Nutr 2008;138:604–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salmon L. Food security for infants and young children: An opportunity for breastfeeding policy? Int Breastfeed J 2015;10:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Canada’s action plan for food security (1998): in response to the World Food Summit Plan of Action. Rep No 1987E. Ottawa: Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frank L. Exploring infant feeding practices in food insecure households: What is the real issue? Food Foodways 2015;23:186–209. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Breastfeeding and food security: the high cost of formula feeding. Toronto: INFACT Canada; 2004. Available: www.infactcanada.ca/Breastfeeding_and_Food_Security.pdf (accessed 2017 May 18). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Sahab B, Lanes A, Feldman M, et al. Prevalence and predictors of 6-month exclusive breastfeeding among Canadian women: a national Survey. BMC Pediatr 2010;10:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Millar WJ, Maclean H. Breastfeeding practices. Health Rep 2005;16(2):23–31.16190322 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dubois L, Girard M. Social inequalities in infant feeding during the first year of life. The Longitudinal Study of Child Development in Québec (LSCDQ 1998–2002). Public Health Nutr 2003;6:773–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Partyka B, Whiting S, Grunerud D, et al. Infant nutrition in Saskatoon: barriers to infant food security. Can J Diet Pract Res 2010;71:79–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dubois L, Farmer A, Girard M, et al. Family food insufficiency is related to overweight among preschoolers. Soc Sci Med 2006;63:1503–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huddleston-Casas C, Charnigo R, Simmons LA. Food insecurity and maternal depression in rural, low-income families: a longitudinal investigation. Public Health Nutr 2009;12:1133–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whitaker RC, Phillips SM, Orzol SM. Food insecurity and the risks of depression and anxiety in mothers and behavior problems in their preschool-aged children. Pediatrics 2006;118:e859–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McLearn KT, Minkovitz CS, Strobino DM, et al. Maternal depressive symptoms at 2 to 4 months post partum and early parenting practices. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2006;160:279–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Finkelstein SA, Keely E, Feig DS, et al. Breastfeeding in women with diabetes: lower rates despite greater rewards. A population-based study. Diabet Med 2013;30:1094–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Canadian Community Health Survey, cycle 2.2, nutrition (2004) — income-related household food security in Canada. HC Publ No 4696. Ottawa: Health Canada, Health Products and Food Branch, Office of Nutrition Policy and Promotion; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Canadian Community Health Survey — annual component (CCHS). Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2016. (updated 2016 Nov. 1). Available: www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&SDDS=3226 (accessed 2017 June 4). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Breastfeeding initiation in Canada: key statistics and graphics (2009–2010). Ottawa: Health Canada; 2012. (updated 2012 June 27). Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-nutrition/food-nutrition-surveillance/health-nutrition-surveys/canadian-community-health-survey-cchs/breastfeeding-initiation-canada-key-statistics-graphics-2009-2010-food-nutrition-surveillance-health-canada.html (accessed 2017 July 15). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Health Canada; Canadian Paediatric Society; Dietitians of Canada; Breastfeeding Committee for Canada. Nutrition for healthy term infants: recommendations from birth to six months. Can J Diet Pract Res 2012;73:204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kramer MS, Kakuma R. Optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;(8):CD003517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Horta BL, Victora CG. Long-term effects of breastfeeding: a systematic review. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ip S, Chung M, Raman G, et al. Breastfeeding and maternal and infant health outcomes in developed countries. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep) 2007; (153):1–186. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frank L. Finding formula: community-based organizational responses to infant formula needs due to household food insecurity. Can Food Stud. In press. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Melchior M, Chastang JF, Falissard B, et al. Food insecurity and children’s mental health: a prospective birth cohort study. PLoS One 2012;7:e52615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kirkpatrick SI, McIntyre L, Potestio ML. Child hunger and long-term adverse consequences for health. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2010;164:754–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McIntyre L, Williams JV, Lavorato DH, et al. Depression and suicide ideation in late adolescence and early adulthood are an outcome of child hunger. J Affect Disord 2013;150:123–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McIntyre L, Wu X, Kwok C, et al. The pervasive effect of youth self-report of hunger on depression over 6 years of follow up. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2017;52:537–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Loopstra R, Tarasuk V. Severity of household food insecurity is sensitive to change in household income and employment status among low-income families. J Nutr 2013;143:1316–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.The Community Action Program for Children (CAPC) and the Canada Prenatal Nutrition Program (CPNP): national projects fund 2004–2008 project showcase. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada, Division of Childhood and Adolescence; 2010. (updated 2011 Feb. 21). Available: www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/hp-ps/dca-dea/prog-ini/funding-financement/npf-fpn/2004-2008/index-eng.php (accessed 2017 June 18). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muhajarine N, Ng J, Bowen A, et al. Understanding the impact of the Canada Prenatal Nutrition Program: a quantitative evaluation. Can J Public Health 2012;103(Suppl 1):eS26–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brownell MD, Chartier MJ, Nickel NC, et al. PATHS Equity for Children Team. Unconditional prenatal income supplement and birth outcomes. Pediatrics 2016;137:e20152992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Loopstra R, Dachner N, Tarasuk V. An exploration of the unprecedented decline in the prevalence of household food insecurity in Newfoundland and Labrador, 2007–2012. Can Public Policy 2015;41:191–206. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li N, Dachner N, Tarasuk V. The impact of changes in social policies on household food insecurity in British Columbia, 2005–2012. Prev Med 2016;93:151–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McIntyre L, Dutton DJ, Kwok C, et al. Reduction of food insecurity in low-income Canadian seniors as a likely impact of a guaranteed annual income. Can Public Policy 2016;42:274–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]