Abstract

Nursing home employees experience high physical and psychosocial workloads, resulting in poor health outcomes. An occupational health/health promotion program, designed to facilitate employee participation, was initiated in three nursing homes. The aim of the current study was to evaluate facilitators and barriers of the program after 3-year implementation. Focus groups with employees and in-depth interviews with top and middle managers were conducted. The Social Ecological Model was used to organize the evaluation. Facilitators and barriers were reported from both managers’ and employees’ perspectives, and were categorized as intrapersonal, interpersonal, institutional, and corporate level. Management support, financial resources, and release time for participation were identified as the three most important factors. Supports from multiple levels including both human and environment, and managers and employees, are important for a successful participatory occupational health/health promotion program.

Health care services are one of the largest sectors in the United States, employing more than 14.3 million individuals, including approximately 7 million professional workers (Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, n.d.). The nursing home sector is the second most hazardous in terms of recognized work-related injuries and illnesses (Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, 2005). In addition, nursing homes have high employee turnover (Trinkoff et al., 2013), posing challenges for staffing levels (Shin, 2013) and resulting in poor resident outcomes and quality of life (Shin, 2013; Trinkoff et al., 2013). Nursing home employees experience high physical workloads and stressful psychosocial work environments (Lapane & Hughes, 2007; Zhang et al., 2011), leading to a range of health problems, such as musculoskeletal disorders, cardiovascular diseases, and poor mental health (Miranda, Gore, Boyer, Nobrega, & Punnett, 2015; Punnett et al., 2009).

Effective health promotion is important to improve employees’ physical and psychosocial well-being. Workplace health promotion has demonstrated positive effects on employee healthy eating behaviors (Maes et al., 2012), physical activity (Conn, Hafdahl, Cooper, Brown, & Lusk, 2009), and weight loss (Anderson et al., 2009), as well as decreases in absenteeism (Kuoppala, Lamminpaa, & Husman, 2008) and increases in work productivity (Cancelliere, Cassidy, Ammendolia, & Cote, 2011), although the literature is mixed and reported sustainability is a problem. The current focus of workplace health promotion efforts has gone beyond traditional health promotion through individual behavior changes. Workplace health promotion now also addresses occupational and environmental influences on health behaviors, through primary and secondary prevention efforts (Ball, Timperio, & Crawford, 2006). Desired outcomes include reduced musculoskeletal injuries and psychosocial stressors, reduced staff turnover, improved work satisfaction, and improved quality of care (Punnett et al., 2009).

The key to a long-term, sustainable workplace program may depend on involving employees in more participatory approaches to program design (Henning et al., 2009; Punnett et al., 2009; Robertson et al., 2013). In a participatory approach, employees are actively engaged in problem identification, decision making, implementation, and evaluation of the program. This approach has been found to benefit intervention effectiveness because employees are well-qualified to identify opportunities and obstacles present in their work environment (Henning et al., 2009). For example, participatory ergonomics has been recommended as a way to design interventions to prevent low back and neck pain in the workplace (Cole et al., 2005; Haro & Kleiner, 2008).

However, participatory programs linking occupational health and health promotion focus not only on individual behavior changes but also on the effect of the physical and psychosocial work environment on individual behaviors, so implementation is more challenging than conventional top-down health promotion programs. A participatory occupational health/health promotion program requires more time, effort, and commitment from the organization (Petterson, Donnersvärd, Lagerström, & Toomingas, 2006). There is little published research regarding how to recruit and engage employers and employees successfully for participatory occupational health/health promotion programs.

BACKGROUND

The current study was conducted as part of the research project “Promoting Physical and Mental Health of Caregivers through Transdisciplinary Intervention (ProCare)” (access http://www.uml.edu/Research/centers/CPH-NEW/projects.aspx). In May 2008, three nursing homes were selected for a participatory program with a broader scope of health promotion. The program’s focus went beyond traditional health promotion activities (e.g., nutrition, exercise, smoking, weight loss), but also included work organization, psychosocial stress, ergonomics concerns, and other occupational health and safety issues (Punnett et al., 2009). The design of the participatory program has been described previously (Zhang, Flum, West, & Punnett, 2015).

At each facility, non-supervisory employees were recruited to form the Health and Wellness (H&W) Team from as many job categories as possible (e.g., nursing assistants, housekeepers, dietary aides, office staff). These H&W Teams, facilitated by the university researchers, met every 2 weeks for 1 hour. The H&W Team meetings aimed to identify issues of concerns, prioritize issues, plan and implement intervention activities, and evaluate these activities. A number of similar activities were initiated in the three facilities, such as requesting the facilities to provide low-cost or free healthy meals onsite, securing clean and uncluttered break areas, asking for a quiet relaxation room for employees to escape from the continual sensory input of jobs, organizing ergonomics (i.e., body mechanics) training, and starting nutrition and weight loss programs. A qualitative evaluation, using focus groups and in-depth interviews, was conducted in the three nursing homes from June to August 2011, 3 years after initiation of the program. Topics covered program effectiveness, motivators and challenges, and sustainability. The objective of the current study was to describe the facilitators and barriers for the participatory occupational health/health promotion program from both managers’ and employees’ perspectives. The analysis was conducted in the context of investigators’ direct observations and field notes.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

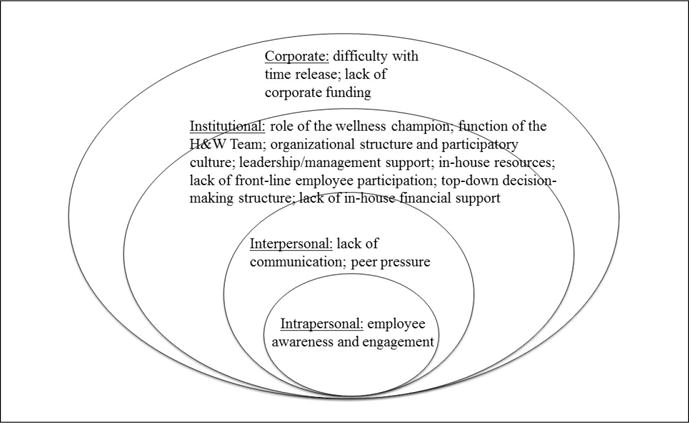

To promote employee participation in workplace health promotion initiatives, previous research has recommended use of an ecological approach (McLeroy, Bibeau, Steckler, & Glanz, 1988). This approach emphasizes that an effective health promotion program requires multiple levels of influence, including intrapersonal, interpersonal, institutional, community, and public policy (McLeroy et al., 1988). Motivators and challenges from multiple levels will influence successful program initiation and implementation in terms of institutional sustainability as well as individual behavior changes. The Social Ecological Model (SEM) for health promotion (McLeroy et al., 1988) provided the theoretical framework for the current study (Figure). The influences of different levels interact with each other and are understood to have reciprocal impacts on the effectiveness of a health promotion program (McLeroy et al., 1988). In the current study, the authors examined factors operating at the corporate level as well as the intrapersonal, interpersonal, and institutional levels because all three nursing homes were operated by a single corporation.

Figure.

Facilitators and barriers for a participatory occupational health/health promotion program: a modified Social Ecological Model.

Note. H&W = health and wellness.

METHOD

Study Design

The study design for this qualitative evaluation of the participatory occupational health/health promotion program included (a) focus groups with H&W Team members; (b) focus groups with other employees; (c) in-depth interviews with individual H&W Team members; (d) in-depth interviews with top managers (i.e., administrators and directors of nursing [DONs]); and (e) in-depth interviews with middle managers (i.e., department heads and unit managers). Data collection sought qualitative information about facilitators and barriers of the participatory program. Information collected from employees and managers was coded from each level of the modified SEM: intrapersonal, interpersonal, institutional, and corporate. An exploratory qualitative design was used because qualitative research provides well-established methods for investigating complex and poorly understood organizational and human phenomena (Mergler, 1999).

Settings

The participating company operates more than 200 nursing homes in 12 states in the eastern United States. Each facility has approximately 100 to 200 employees, of whom 50 to 80 are clinical staff members. The three nursing homes participating in the current study were for-profit, non-unionized facilities.

Sample and Data Collection

Focus Groups

At each center, one focus group with the H&W Teams and two focus groups with other employees were scheduled to evaluate the effectiveness, motivators and challenges, and sustainability of the program. Focus groups met for 60 minutes, with a limit of 10 participants, in a private room onsite. Each focus group participant was compensated $20 for completing the session.

Interviews

In-depth interviews with individual H&W Team members were scheduled for 15 minutes each in a private room to elicit more detailed information about their participation in the H&W Teams. In-depth interviews with top and middle managers were scheduled for 30 minutes each in their office to learn their views on the effectiveness, accomplishments, motivators and challenges, and sustainability of the program.

One experienced outside evaluator and two trained research assistants (Y.Z., R.K.) conducted focus groups and interviews. The key topics were similar for focus groups and interviews (Table 1). Researchers explained the purpose and procedure and requested participants to sign a consent form. All focus groups and interviews were audiorecorded and professionally transcribed. The study was approved by the University of Massachusetts Lowell Institutional Review Board.

TABLE 1.

FOCUS GROUP AND INTERVIEW SAMPLE QUESTIONS

| H&W Team Focus Group Topics | Employee Focus Group Topics | Management Interview Topics |

|---|---|---|

| 1. What do you see as the major accomplishment of the H&W Team? | 1. Are you aware of the wellness activities or programs at the center? | 1. What do you see as the major accomplishment of the H&W Team? |

| 2. What do you see as the major obstacles standing in the way of progress for the H&W Team? | 2. Have you been involved in the H&W Team or H&W activities? | 2. What kinds of support do you give to the H&W Team? |

| 3. How do you think more employees could be involved in planning and supporting H&W? | 3. What do you see as the major accomplishments of the H&W Team? | 3. Could you discuss how the H&W Team communicate with you? With management? With other employees? |

| 4. What do you see as the major obstacles standing in the way of progress for the H&W Team at your center? | 4. How well does the team function as a team? Are there ways this could be improved? | 4. What do you see as the major obstacles standing in the way of progress for the H&W Team? |

| 5. How do you handle employee suggestions and concerns? | 5. What kinds of support have you been able to get from the H&W Team? | 5. What effects have the programs of the H&W Team had on the rest of the employees at your center? |

| 6. What kinds of additional support does the H&W Team need from the center? | 6. How well has the team been able to address work-related issues? | 6. How do you handle employee suggestions and concerns? |

Note. H&W = health and wellness

Data Analysis

A three-step data analysis procedure was implemented. A provisional “start list” of themes, relevant to the social ecological levels, was developed based on the existing literature, question categories used in the focus groups and interviews, and the researchers’ own experience. Specific themes at any level included staff, leadership, organizational issues/structures, resources, and time. Due to the large amount of information collected in the focus groups and interviews (N = 37), transcripts were first analyzed by a technical NVivo expert who completed initial coding in NVivo 9, a software package for qualitative analysis, using the “start list.” Identified subthemes were allowed to emerge during the analysis process until saturation was achieved. Two research assistants (Y.Z., R.K.), who participated in both the program implementation and evaluation process, reread the transcripts to verify the themes and subthemes relevant to the SEM and identify any further themes or subthemes that were not revealed by the initial NVivo analysis. The theme structure and quotes according to the SEM were discussed by the research team. Small discrepancies among team members were resolved through discussions on interpretation, consensus building, and refinement of theme definitions as needed.

RESULTS

Eight focus groups (three with the H&W Teams, five with other employees) were conducted in the three centers from June to August 2011. A total of 58 employees participated, of whom 90% were female (n = 52). By ethnicity, 60% (n = 35) were White, 21% (n = 12) were Black, 15% (n = 9) were Hispanic, 2% (n = 1) were Asian, and 2% (n = 1) were Middle Eastern.

Eleven individual interviews were completed with H&W Team members. All interviewees were female. Eight were White, one was Black, and two were Hispanic individuals. Five individual interviews with top management were completed. All administrators and DONs were White, non-Hispanic, and four were female. Thirteen middle managers were also interviewed, of whom eight were female, 11 were White and two were Hispanic.

The findings were organized according to the levels of the modified SEM (Table 2). Both facilitators and barriers for the participatory program are described, although at some levels, only facilitators or barriers (but not both) were identified. In general, there were few differences between employees and managers about the issues discussed. Findings from the three centers revealed good internal consistency.

TABLE 2.

A MODIFIED SOCIAL ECOLOGICAL MODEL TO EVALUATE FACILITATORS AND BARRIERS FOR A PARTICIPATORY OCCUPATIONAL HEALTH/HEALTH PROMOTION PROGRAM

| Factors/Facilitators and Barriers | Direct Quotes/Evidence Supporting Findings |

|---|---|

| Intrapersonal | |

| Facilitators | |

| Employee awareness and engagement | “The involvement is the biggest piece.” [middle management interviews] |

| Interpersonal | |

| Barriers | |

| Lack of communication | “…face-to-face, one-on-one, spreading the word out, being up on the floor…instead of… half dozen people around a table deciding what the rest of the building wants.” [middle management interviews] |

| Peer pressure | “But the biggest, the hardest piece of it… is the peer pressure people feel in leaving their unit to go do something like this.” [employee focus groups] |

| Institutional | |

| Facilitators | |

| Role of the wellness champion | The wellness champions led the H&W Teams and bridged mutual communications between the team, managers, and employees. |

| Function of the H&W Team | “We’re a very small team in this building. But we really try and include everybody in what we do.” [H&W Team focus groups] |

| Organizational structure and participatory culture | Most managers discussed H&W as part of their organizational structure. The participatory culture emerged in the program as an important motivator. |

| Leadership/management support | Management support was indicated in a number of ways, including enabling staff to take time off for meetings and activities, providing space for meetings and activities, as well as providing encouragement. |

| In-house resources | Using existing in-house resources was a motivator for the program. |

| Barriers | |

| Lack of front-line employee participation | “It’s awfully hard…. We cannot get the aides off the floor because they’re either understaffed or, so it makes it really hard.” [H&W Team focus groups] |

| Top-down decision-making structure | “It took a long time to implement programs due to the ‘chain of command’” and “[decisions] start from the top to the bottom.” [H&W Team focus groups] |

| Lack of in-house financial support | Management verbal support was not necessarily backed up by financial resources. |

| Corporate | |

| Barriers | |

| Difficulty with time release | “I think it’s time. With patient care, it’s difficult. They don’t have always the same time for breaks. They don’t have the same time for lunch.” [middle management interviews] |

| Lack of corporate funding | No funds were allocated in the budgets for employee H&W in three centers. |

Note. H&W = health and wellness.

Intrapersonal Factors

Facilitators. Employee awareness and engagement

Employee awareness and engagement in the health and wellness activities was considered by managers and employees as central to the program. Topics mentioned included growth of staff awareness, staff buy-in, and engagement from staff. Awareness of the team or activities was uneven among employees on different shifts. Most day shift employees were aware of the teams, but the evening and night shift employees had less awareness [employee focus groups]. Staff buy-in and employee engagement in the program varied. In the two centers where the H&W Teams included members who had access to many departments, or who were at a higher level of the institutional hierarchy, employees demonstrated higher engagement in the program [employee focus groups].

Interpersonal Factors

Barriers. Lack of communication

Communication was reported from focus groups and interviews from the following perspectives: (a) between managers and the H&W Team members; (b) between managers and other employees; (c) between the H&W Team members and other employees; and (d) among employees. Managers and employees recognized the existing communication problems as a big barrier in dissemination of activities. In addition, the way that information was shared was reported differently. For example, although the H&W Team members expressed spending efforts on disseminating the activities within the facility [H&W Team focus groups], other employees and middle managers reported frustration with the team members primarily talking to each other, rather than trying to get more front-line staff involved [employee focus groups and middle manager interviews].

Peer pressure

Peer pressure regarding their work role was expressed by employees in the focus groups as a barrier to participating in the health and wellness activities. Employees indicated that the high priority of their caregiving responsibilities caused them to experience peer pressure against being involved in the activities [employee focus groups], because participating in the activities often meant that they had to shift caregiving responsibilities to their coworkers or leave residents in a potentially unsafe situation. Peer pressure was also closely related to short staffing and time strain in the organizational structure that limited employees’ participation in the health and wellness activities.

Institutional Factors

Facilitators. Role of the wellness champion

The administrator appointed a “wellness champion” at each center as the key liaison of the program. The wellness champions convened and facilitated the team meetings and bridged communications between the teams, managers, and employees. Employees and managers cited the wellness champion as the leader of the wellness efforts and mentioned the importance of having someone to act as a motivational force behind the team’s ideas. Wellness champions were seen as the “go to” person for employee health and wellness. However, there were challenges associated with the role of the wellness champion. None had a reduction in other duties in exchange for taking on this role. Some expressed their struggle with the added work beyond their normal job responsibility [H&W Team member interview].

Function of the H&W Team

Several factors associated with the H&W Teams were discussed by managers and employees, such as program ownership, empowerment, skill-building, setting appropriate goals, and consistent team participation. The presence and function of the teams were considered as a big motivator for the program. Empowerment and skill-building were integral benefits for many team members. Recognition of and respect for their efforts was a key topic when the teams evaluated their own work. The team members expressed, “We’re a very small team in this building. But we really try and include everybody in what we do” [H&W Team focus groups].

Organizational structure and participatory culture

Top management in the three centers discussed health and wellness as part of their everyday work and viewed the wellness champion and H&W Team as part of the organizational structure. They also mentioned the participatory culture that emerged from the program as one of the most important motivators for the program.

Leadership/management support

Among the facilitators that were reported by team members, management support was most commonly cited, referring to both top and middle managers. An active and engaged leadership played a critical role in the program. Top management also saw management support as a motivator for the efforts of the team, in terms of enabling staff members to take time off for meetings and activities, providing space for meetings and activities, as well as providing encouragement.

In-house resources

Existing in-house resources were seen facilitators for the program. For example, one center offered yoga classes taught by one of the nurses; the dietician in another center offered a “biggest loser” program. These programs were well received by staff members and spread around the entire center [employee focus groups]. These activities suggested that one positive trend that seemed to be emerging from necessity was to ask in-house staff to take on health and wellness projects.

Barriers. Lack of Front-Line Employee Participation

Front-line employee participation can be a serious challenge. In all three centers, employees brought up the issues of short staffing, time strain, and clinical responsibilities as primary causes for limitations to participation. One H&W Team member expressed, “Our staff has been cut to the point where there’s no leeway for anybody…they just weren’t be able to pull themselves away from the residents.” As a result, front-line employee participation in the H&W Teams suffered. It was hard for clinical staff because they “can’t leave the floor because of the staffing,” and their “commitment to their residents, that they don’t feel that they can leave the floor and leave the residents.” The identification of issues of concerns, as well as planning, implementation, and evaluation of intervention activities were limited due to the lack of front-line employee participation.

Top-Down Decision-Making Structure

The H&W Team believed that the decision-making structure within the three facilities was a barrier for the progress of the program. The H&W Team members described that it took a long time to implement programs due to the “chain of command” and “[decisions] start from the top to the bottom.” One team member said, “It’s very hierarchal around here.” Health and wellness programs were easily delayed in the process of waiting for or requesting follow-up from management.

Lack of In-House Financial Support

H&W Team members stated that management verbal support was not necessarily backed up by financial resources. For example, in one facility, the administrator expressed, “I want real, thoughtful projects…the approval piece of it is that we do have some autonomy as the leader of a building, to fund and to ride within our budgets…” However, one team member in the same facility said, “Management is always worried about the bottom line, the dollar.” In addition, although managers expressed that they would like to support the employee health and wellness program, they also voiced ambivalence about it in light of other pressing concerns, such as resident care.

Corporate Factors

Barriers. Difficulty with time release

Time was stated by team members, employees, and managers as the biggest obstacle for the program. Not only was release time a universal challenge, but other issues, such as finding convenient time for meetings and activities, were also reported. A middle manager said, “I think the major obstacle is the time frame…you know [if it was] off the clock they may not be so interested in it.” Time and scheduling issues were often stated in conjunction with staffing and lack of participation. One suggestion from managers and employees was to shorten the time period for the team meetings or activities [employee focus groups and top management interviews]. Another suggestion that might overcome the challenge of time was to treat the team meetings and activities similar to the way staff training was treated [employee focus groups], so that staff members could be relieved from duties without worrying about leaving residents unsafe.

Lack of corporate funding

Each center was being provided with a small annual budget ($700) for health promotion activities by the corporate company when the program was started in May 2008. This budget was cut from the corporate level due to economic crisis after 6 months of the program initiation. Administrators and team members identified no funding from corporate as a barrier for the program. Most team members expressed frustration at the lack of funds for activities. Two centers engaged in regular fundraising, and the effort required seemed to take away from time that would have been better spent on actual activities.

DISCUSSION

The current study reports the facilitators and barriers for a participatory occupational health/health promotion program in three nursing homes at the intrapersonal, interpersonal, institutional, and corporate levels. Notably, similar opinions were obtained on many topics from the four groups of participants: H&W Team members, front-line employees, middle managers, and top management.

Some of the findings were anticipated, whereas others were more innovative. The presence of a wellness champion and the active functioning of the H&W Team were seen by managers and employees alike as facilitators to the program. Barriers to the program included limited front-line employee participation, poor communication, top-down decision-making structure, and lack of financial resources. The root cause for low front-line employee participation was primarily the lack of release time for employees. In turn, this was closely associated with employee workload. Although not discussed specifically by participants, there are important upstream determinants of tight staffing and high workloads in the long-term care setting, especially with inadequate Medicaid reimbursement rates (Lazar, 2015). The high turnover rate in nursing homes (Donoghue, 2010) and tight staffing levels (Feuerberg, 2001) are well documented and create a vicious cycle because they contribute to work strain among employees, which in turn increases turnover (Zhang, Punnett, & Gore, 2014). Psychosocial stress had already been documented as a prevalent concern in all three of these centers (Zhang et al., 2011).

Consistent with other findings (Lowe, Schellenberg, & Shannon, 2003), communication, management support, job demands, and resources were raised by employees as strong predictors of healthy work environment. An innovative idea raised from the participatory program is to take advantage of in-house resources to promote employee health and wellness when financial resources in the organization are too limited to engage outside assistance.

Leadership/management support was identified as a key factor supporting the participatory program in two of three centers. Leadership development has previously been suggested (Kelloway & Barling, 2010) as a main target for workplace interventions because leadership quality is associated with diverse employee outcomes, such as workplace injuries, stress, cardiovascular disease, and alcohol consumption (Kelloway & Barling, 2010). Middle managers should be included in that leadership development effort because they have so much direct contact and communication with employees that their behavior can have a great effect on employee behavior, including but not limited to participation in workplace programs. Zohar (2002) reported that training of middle managers could improve sub-unit safety. Petterson et al. (2006) emphasized the importance of involving middle management in early intervention planning and decisions, based on an intervention to empower nursing staff working in home care. A successful occupational health/health promotion program could benefit from involving top and middle management in program planning and implementation, such as by more broadly advocating the role and function of the H&W Team and actively supporting employee participation in the health and wellness activities. The discrepancies regarding management support expressed from managers and employees in the current study suggest a need for leadership development training at both top- and middle-management levels, indicating that future interventions should be conducted at several levels simultaneously.

Safety-specific leadership development training has been documented as an effective intervention in improving leaders’ own safety attitude, intention to promote safety in the workplace, and safety-related self-efficacy in health care organizations (Mullen & Kelloway, 2009). Similarly, leadership development training with a focus on health protection and health promotion may be effective in promoting workplace participatory occupational health/health promotion programs. Simple, practical strategies could be implemented, such as, publicly recognizing employees who participate in the program, attend the H&W Team meetings on a regular basis, and actively participate in employee health and wellness activities in person.

Other strategies to promote a workplace participatory occupational health/health promotion program may entail substantial organizational change, such as build the dedicated roles of the wellness champion and members of the H&W Team within the organizational structure; make it possible for members to attend the H&W Team meetings during the work shift; allow employees to participate in the health and wellness activities on paid time; allocate a budget for employee health and wellness activities; and empower front-line employees in the decision-making process. Although well-known financial constraints in the long-term sector make these preconditions difficult to achieve in practice, good leadership can establish a climate in which employees feel valued and empowered and in turn may be health-promoting.

STUDY STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

The strengths of the current study include the large number of focus groups and in-depth interviews that were conducted; the range of sites and departments from which participants were drawn; and the coordinated scripts for paired focus groups and management interviews. The generalizability of the results may be limited to the extent that these three nursing homes were all owned and operated by a single corporation and were all located in Massachusetts. Although the participatory programs at the three centers were initiated by the same investigators, different health and wellness activities were implemented across these centers. This difference in activities complicates direct comparisons between nursing homes but increases the generalizability of the current findings regarding the facilitators and barriers to a participatory occupational health/health promotion program in this occupational setting.

CONCLUSION

The current study used a modified SEM to evaluate the facilitators and barriers of a participatory occupational health/health promotion program from managers’ and employees’ perspectives. Management support, sufficient financial resources, and time release for program participation were the three factors identified as most important for the success of the program. The presence of a functional committee with an active coordinator was seen as essential for good communication within the workplace and motivating employee participation. The results from the current study suggest that supports from multiple levels, determined by human and environmental factors, are important for a successful participatory program focused on health. Lessons learned from the current study can guide future participatory occupational health/health promotion programs in nursing homes and other workplaces that share similar resources and challenges.

Keypoints.

Zhang, Y., Flum, M., Kotejoshyer, R., Fleishman, J., Henning, R., & Punnett, L. (20xx). Workplace Participatory Occupational Health/Health Promotion Program: Facilitators and Barriers Observed in Three Nursing Homes.

1 The Social Ecological Model provides an effective multi-level framework for assessing facilitators and barriers of a workplace participatory occupational health/health promotion program.

2 Management support, financial resources, and release time for employee participation were identified as the three most important factors related to the success of a workplace participatory occupational health/health promotion program.

3 A successful occupational health/health promotion program benefits from leadership development training at both top- and middle-management levels with a focus on health protection and health promotion.

4 Organizational support for the dedicated roles of a wellness champion and an employee team, empowerment of front-line employees in decision making, and a budget for employee health and wellness activities are all important for the success and sustainability of a workplace participatory occupational health/health promotion program.

Acknowledgments

The Center for the Promotion of Health in the New England Workplace is supported by a grant (1 U19 OH008857) from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). This work is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIOSH.

Footnotes

The authors have disclosed no potential conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise.

References

- Anderson LM, Quinn TA, Glanz K, Ramirez G, Kahwati LC, Johnson DB, Katz DL. The effectiveness of worksite nutrition and physical activity interventions for controlling employee overweight and obesity: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2009;37:340–357. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball K, Timperio AF, Crawford DA. Understanding environmental influences on nutrition and physical activity behaviors: Where should we look and what should we count? International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2006;3:33. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-3-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor. Lost-worktime injuries and illnesses: Characteristics and resulting time away from work. 2004 (n.d.) Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/osh2_12132005.pdf.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor. Career guide to industries, 2010–11. 2005 Retrieved from http://health.uc.edu/ahec/PDFs/Health%20Services%20Industry%20Overview.pdf.

- Cancelliere C, Cassidy JD, Ammendolia C, Cote P. Are workplace health promotion programs effective at improving presenteeism in workers? A systematic review and best evidence synthesis of the literature. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:395. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole D, Rivilis I, Van Eerd D, Cullen K, Irvine E, Kramer D. Effectiveness of participatory ergonomic interventions: Summary of a systematic review. 2005 doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2007.08.006. Retrieved from http://www.iwh.on.ca/system/files/documents/summary_pe_effectiveness_2005.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Conn VS, Hafdahl AR, Cooper PS, Brown LM, Lusk SL. Meta-analysis of workplace physical activity interventions. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2009;37:330–339. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donoghue C. Nursing home turnover and retention: An analysis of national level data. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2010;29:89–106. doi: 10.1177/0733464809334899. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feuerberg M. Appropriateness of minimum nurse staffing ratios in nursing homes. Report to Congress: Phase II final report. 2001 Retrieved from http://www.all-health.org/BriefingMaterials/Abt-Nurse-StaffingRatios(12-01)-999.pdf.

- Haro E, Kleiner BM. Macroergonomics as an organizing process for systems safety. Applied Ergonomics. 2008;39:450–458. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2008.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henning R, Warren N, Robertson M, Faghri P, Cherniack M, The CPH-NEW Research Team Workplace health protection and promotion through participatory ergonomics: An integrated approach. 2009 doi: 10.1177/00333549091244S104. Retrieved from http://www.publichealthreports.org/issueopen.cfm?articleID=2243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kelloway K, Barling J. Leadership development as an intervention in occupational health psychology. Work & Stress. 2010;24:260–279. doi: 10.1080/02678373.2010.518441. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuoppala J, Lamminpaa A, Husman P. Work health promotion, job well-being, and sickness absences: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2008;50:1216–1227. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31818dbf92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapane KL, Hughes CM. Considering the employee point of view: Perceptions of job satisfaction and stress among nursing staff in nursing homes. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2007;8:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazar K. Nursing home patients put adrift. The Boston Globe. 2015 Mar 24; Retrieved from http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1P2-37786680.html.

- Lowe GS, Schellenberg G, Shannon HS. Correlates of employees’ perceptions of a healthy work environment. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2003;17:390–399. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-17.6.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maes L, Van Cauwenberghe E, Van Lippevelde W, Spittaels H, De Pauw E, Oppert JM, De Bourdeaudhuij I. Effectiveness of workplace interventions in Europe promoting healthy eating: A systematic review. European Journal of Public Health. 2012;22:677–683. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckr098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education Quarterly. 1988;15:351–377. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mergler D. Combining quantitative and qualitative approaches in occupational health for a better understanding of the impact of work-related disorders. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health. 1999;25(Suppl. 4):54–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda H, Gore RJ, Boyer J, Nobrega S, Punnett L. Health behaviors and overweight in nursing home employees: Contribution of workplace stressors and implications for worksite health promotion. The Scientific World Journal. 2015;2015:915359. doi: 10.1155/2015/915359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen JE, Kelloway EK. Safety leadership: A longitudinal study of the effects of transformational leadership on safety outcomes. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology. 2009;82:253–272. doi: 10.1348/096317908X325313. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Petterson IL, Donnersvärd HÅ, Lagerström M, Toomingas A. Evaluation of an intervention programme based on empowerment for eldercare nursing staff. Work & Stress. 2006;20:353–369. doi: 10.1080/02678370601070489. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Punnett L, Cherniack M, Henning R, Morse T, Faghri P, The CPH-NEW Research Team A conceptual framework for integrating workplace health promotion and occupational ergonomics programs. 2009 doi: 10.1177/00333549091244S103. Retrieved from http://publichealthreports.org/archives/issueopen.cfm?articleID=2241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Robertson M, Henning RA, Warren N, Nobrega S, Dove-Steinkamp M, Tibirica L, Bizarro A. The Intervention Design and Analysis Scorecard: A planning tool for participatory design of integrated health and safety interventions in the workplace. Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine. 2013;55(Suppl. 12):S86–S88. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin JH. Relationship between nursing staffing and quality of life in nursing homes. Contemporary Nurse. 2013;44:133–143. doi: 10.5172/conu.2013.44.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinkoff AM, Han K, Storr CL, Lerner N, Johantgen M, Gartrell K. Turnover, staffing, skill mix, and resident outcomes in a national sample of US nursing homes. Journal of Nursing Administration. 2013;43:630–636. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Flum M, Nobrega S, Blais L, Qamili S, Punnett L. Work organization and health issues in long-term care centers: Comparison of perceptions between caregivers and management. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 2011;37(5):32–40. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20110106-01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Flum M, West C, Punnett L. Assessing organizational readiness for a participatory occupational health/health promotion intervention in skilled nursing facilities. Health Promotion Practice. 2015;16:724–732. doi: 10.1177/1524839915573945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Punnett L, Gore R. Relationships among employees’ working conditions, mental health, and intention to leave in nursing homes. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2014;33:6–23. doi: 10.1177/0733464812443085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zohar D. Modifying supervisory practices to improve subunit safety: A leadership-based intervention model. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2002;87:156–163. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.1.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]