Abstract

Objectives

Electrifying a coronary guidewire may be a simple escalation strategy when trans-septal needle puncture is unsuccessful.

Background

Radiofrequency energy to facilitate trans-septal puncture through a dedicated device is costly and directly through a trans-septal needle may be less safe. Our technique overcomes these limitations.

Methods

The technique was used in patients when trans-septal needle penetration failed despite excessive force or tenting of the atrial septum. A coronary guidewire, connected to an electrosurgery pencil, was advanced through the trans-septal needle, dilator, and sheath to perforate the interatrial septum during a short burst of radiofrequency energy. With the guidewire tip no longer “active,” the dilator and sheath were advanced safely over the wire into the left atrium.

In posthoc validation, radiofrequency assisted Brockenbrough needle and coronary guidewire punctures were made in freshly explanted pig hearts and compared under microscopy.

Results

Eight patients who required trans-septal access for structural intervention were escalated to a guidewire electrosurgery strategy. Six patients had thickened fibrotic septum and two had prior surgical patch repair. Crossing was successful in all patients with no procedure related complications.

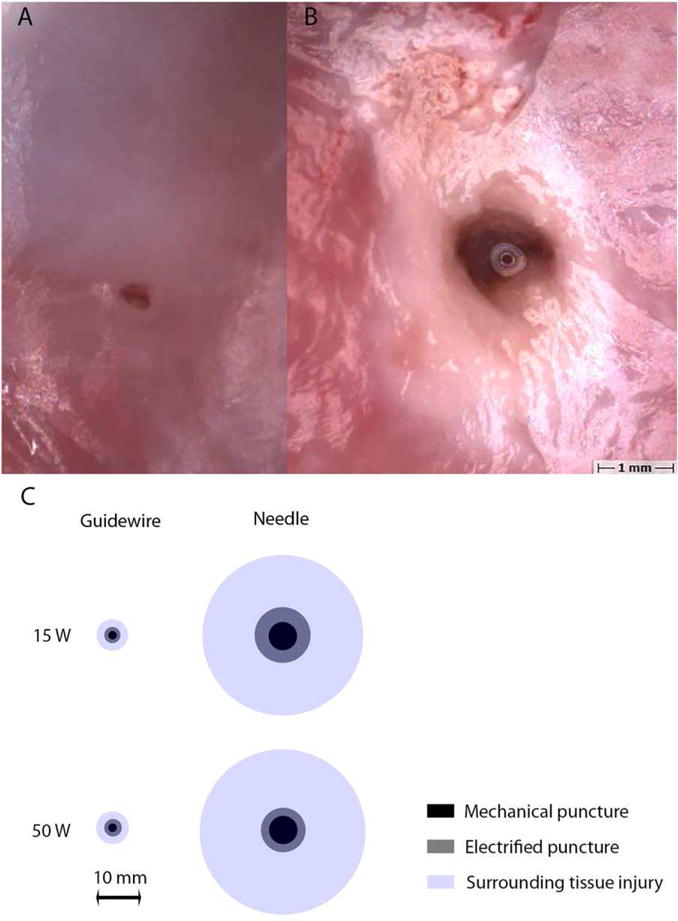

The size of punctures (1.11 ± 0.40 mm vs 0.37 ± 0.08 mm, P = .009) and blanched penumbra (3.62 ± 1.23 mm vs 0.72 ± 0.29 mm, P = .003) in pig atrial septum were larger with an electrified needle than electrified guidewire. The hole generated by the electrified guidewire was smaller than by the nonelectrified needle.

Conclusions

When conventional trans-septal puncture fails, a coronary guidewire can be used to deliver brief radiofrequency energy safely and effectively. This technique is inexpensive and accessible to operators.

Keywords: electrophysiology, left atrial appendage closure, mitral valve disease, percutaneous intervention, structural heart disease intervention, trans-septal catheterization

1 INTRODUCTION

Radiofrequency energy has been used to facilitate atrial septal crossing when conventional needle crossing proves difficult or dangerous due to excessive force and risk of exiting the left atrial free wall. Dedicated trans-septal radiofrequency wires (Nykanen Radiofrequency Perforation Catheter, Baylis Medical Company, Montreal, QA) and needles (NRG trans-septal needle, Baylis Medical Company) are safe and effective at crossing the interatrial septum [1–3]. However, these technologies are costly and may not be readily available in every catheter laboratory. Therefore, directly electrifying the Brockenbrough needle has become popular practice in some institutions [4,5], but with increased risk. There remains a risk of posterior left atrial wall puncture from the sharp needle. The penumbra of injury from an 0.032″ electrified needle into an inadvertent target may be larger than the penumbra of injury of a normal needle. Also, there is only a short distance from needle to dilator, with increased risk of even larger perforation as both need to be advanced in tandem. Furthermore, electrifying the needle can cause tissue coring during septal traversal, potentially increasing embolization risk [6]. Crossing the interatrial septum with an 0.014″ coronary guidewire during brief electrification may mitigate these risks by applying more focused energy with less damage. Once across the septum and no longer electrified, the risk of inadvertent posterior left atrial wall perforation from the floppy wire tip is minimal. A nonradiofrequency alternative is to use a commercial 0.014″ nitinol trans-septal J-shaped guidewire (Safe Sept, Pressure Products, Inc.) which employs similar principles of temporary “sharpness,” in this case by adopting a J-shape once out of the needle [7,8].

We report on the simple and safe use of radiofrequency energy delivered through a 0.014″ coronary guidewire connected to an electrosurgery radiofrequency generator to cross fibrotic, thickened, or aneurysmal atrial septa.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

The Henry Ford Hospital Institutional Review Board approved this retrospective review of clinical outcomes. In patients requiring trans-septal access, conventional trans-septal puncture was attempted under transesophageal echocardiography and fluoroscopy guidance. All patients were anticoagulated with unfractionated heparin, achieving an activated clotting time between 250 and 350s, prior to attempting trans-septal puncture. An 8.5 Fr Swartz curve trans-septal dilator and introducer sheath (typically Fast-Cath SL1, St Jude Medical, Minnesota) were advanced into the superior caval vein over an 0.032″ wire and withdrawn into the right atrium to abut the interatrial septum. Crossing was initially attempted with a coaxial Brockenbrough-type needle (BRK-1 extra sharp, St Jude Medical, Minnesota). Patients were escalated to a guidewire electrosurgery strategy if needle crossing was unsuccessful. This was determined as failure of needle penetration despite several attempts at an optimal trajectory with excessive force and tenting of the interatrial septum. A stylet was not routinely used to assist in septal crossing. The “back end” of a coronary guidewire was not used because of the risk of penetration through the atrial free wall, especially as the wire, needle, and dilator need to be advanced in tandem into the left atrium to prevent shearing of the wire coating by the needle into the left atrium. Instead, the soft tip of an 0.014″ coronary guidewire (Confianza Pro-12 or Astato XS-20, Asahi-Intecc, Nagoya, Japan) was advanced antegrade through the needle to abut the atrial septum. The Astato XS-20 guidewire (180 or 300 cm) has a tapered straight tip with a high tip load of 20 g, high shaft support, and a PTFE insulated shaft. Similarly, the Confianza Pro 12 has a tapered uncoated tip with a high tip load of 12 g, high shaft support and with insulated shaft. These features make these wires suitable for focusing electrosurgery charge for tissue penetration and subsequent delivery of a balloon or dilator and sheath. The back end of the wire was connected via a hemostat to an electrosurgery pencil and generator (Valleylab Force FX, Medtronic, Minneapolis, Minnesota) set to 50 W “pure cut” mode. A dispersive electrode (“grounding pad”) was attached externally to the patient’s body. Radiofrequency energy was delivered through the wire for <1 s as the wire was advanced through the atrial septum into the left atrium (Figure 1). With current turned off, the wire tip was no longer “active” and was safely advanced into a pulmonary vein. Then the needle, dilator, and sheath were advanced safely with the wire into the left atrium (n = 5). Alternatively, at the operator’s discretion, the dilator and needle were withdrawn and 2.5–5.0 mm noncompliant balloons were advanced over the wire and inflated at the septum prior to crossing with the sheath (n = 3). When advancing needle with wire, care was taken to do so in tandem to avoid shearing of the guidewire polymer coating into the left atrium. Further upsizing with dilatation or septostomy was performed as required and the septum closed according to operator preference and patient clinical characteristics.

FIGURE 1.

Electrified guidewire traversal. A, Left anterior oblique fluoroscopic projection showing crossing guidewire in the left atrium with coaxial trans-septal sheath dilator and needle in the right atrium. B, X-plane transesophageal echocardiography image as the electrified guidewire (white arrow) crosses the atrial septum. Microbubbles from radiofrequency energy delivery are seen (circled). C, The uninsulated back end of an Astato guidewire is connected to an electrosurgery pencil with a hemostat. The tip of the guidewire is seen protruding from the BRK-1 needle and SL1 dilator and sheath. LA, left atrium; RA, right atrium [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Post-hoc validation of the concept was performed in freshly explanted pig hearts in a warm saline bath. A Brockenbrough needle in a trans-septal dilator and sheath was used to puncture the interatrial septum with standard mechanical force and, at adjacent sites, with radiofrequency energy through the needle at 15 W and 50 W. A parallel series of punctures were made with an 0.014″ coronary wire (Astato XS 20, Asahi). Punctures were also made in the aorta to simulate inadvertent aortic root puncture, and in the interventricular septum, as radiofrequency-assisted crossing has been used in patients to access the left ventricular endocardium [9]. To deliver radiofrequency energy, the back ends of the needle and guidewire were connected to an electrosurgery pencil and generator with a hemostat and a dispersive electrode was placed in a saline bath. Measurements of the hole and the visible surrounding tissue injury were made under microscopy at ×30magnification.

Statistical analysis comparing needle and guidewire holes was performed using two-tailed paired t-tests for each tissue type.

3 RESULTS

Eight patients who required trans-septal access for structural left heart procedures between August 2016 and June 2017 had initial unsuccessful attempts at conventional trans-septal needle puncture due to increased septal thickness and fibrosis (n = 6) or surgical patch repair (n = 2) causing excessive tenting without needle penetration. All were escalated to undergo electrosurgery-assisted wire crossing through the trans-septal needle, dilator, and sheath system already in place (Table 1). Two operators independently performed this technique.

TABLE 1.

Patient demographics and procedure characteristics

| Age and gender | Septal anatomy | Trans-septal catheter | Needle | Energized wire | Balloon preparation | Catheter and septostomy details | Procedure | Septal closure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 49 yr male | Thick/fibrosed septum | 8.5Fr SL1 | BRK1 XS | Confianza Pro-12 | Viatrac Plus peripheral dilatation catheter 5.0 × 40 mm | 14 × 40 Armada balloon over a Toray wire, 14F Edwards E-sheath | TMVR 29 mm Edwards S3 | 10 mm Amplatzer septal occluder |

| 78 yr male | Thick/fibrosed septum | 8.5Fr SL1 | BRK1 XS | Confianza Pro-12 | 2.5 × 20 mm NC Emerge Rx balloon, 5.0 × 20 mm Viatric Plus peripheral dilatation catheter | 14Fr Watchman delivery sheath | LAA closure—Watchman 30mm | None |

| 81 yr female | Thick/fibrosed septum | 8.5Fr SL1 | BRK1 XS | Amputated Confianza Pro-12 | 4.0 × 15 mm NC Emerge Rx balloon | 14Fr Watchman delivery sheath | LAA closure-27 mm Watchman | None |

| 71 yr male | Thick/fibrosed septum | 8.5Fr SL1 | BRK1 XS | Amputated Confianza Pro-12 | None | 18Fr dilator, 24Fr Mitra-Clip delivery system | MitraClipx2 | None |

| 78 yr male | Postsurgical repair | 8.5Fr SL1 | BRK1 XS | Astato XS 20 | None | 14 × 40 mm Armada balloon over a Toray wire, Edwards 14Fr E-sheath | TMVR—26 mm Edwards S3 | None |

| 67 yr male | Postsurgical repair | 8.5Fr SL-1 | BRK1 XS | Astato XS 20 | None | No balloon, 6Fr Torqueview, 6Fr Torqueview, 5Fr Torqueview | PVL closure | None |

| 76 yr female | Thick/fibrosed septum | 8.5Fr SL1 | BRK1 XS | Astato XS 20 | None | 24Fr Mitra-Clip delivery system | MitraClip | None |

| 85 yr female | Difficult trajectory | 8.5Fr Agilis medium curl | None | Astato XS 20 | None | 14 × 40 Armada balloon over a Toray wire, 14F Edwards E-sheath | TMVR—26 mm Edwards S3 | 25 mm Gore Cardioform septal occluder |

Crossing was successful in all patients attempted. In one patient, crossing required a third attempt following amputation of the Confianza tip. In retrospect, this was likely because the needle was exposed beyond the dilator during these attempts, which dissipated radiofrequency energy beyond the wire tip to the needle and blood pool. There were no complications resulting from the trans-septal crossing. Four patients proceeded to balloon septostomy. One had device closure of the atrial septal hole at the end of the procedure.

Fifty four punctures were made with electrified and nonelectrified Brockenbrough needle and coronary guidewire in the interatrial septum, interventricular septum, and aorta of freshly explanted pig hearts (Figure 2). Traversal was instantaneous with a guidewire at both energy settings, 1–2 s with a needle at 50 W, and 2–5 s at with a needle at 15 W. The size of the hole created with radiofrequency was larger than with mechanical force alone, with a visible penumbra of tissue damage. In the atrial septum, at 50 W, the diameter of the hole (0.99 ± 0.38 vs 0.39 ± 0.11 mm) and penumbra of blanched tissue (3.68 ± 0.74 vs 0.73 ± 0.22 mm) were consistently larger with the electrified needle compared with the electrified guidewire (Figure 1). The size of the holes and tissue damage was relatively smaller in the aorta and larger in the interventricular septum compared with the interatrial septum, though still larger with an electrified needle than electrified guidewire (Table 2).

FIGURE 2.

Atrial septal punctures in swine. A, Microscopy image of electrified guidewire puncture at 50W with healthy surrounding tissue. B, Microscopy image of electrified trans-septal needle puncture at 50 W with a large penumbra of blanched tissue. C, Scaled representation of mean diameters of punctures (gray) and surrounding tissue damage (blue) in pig atrial septum with coronary guidewire and trans-septal needle at 0 W (inner black circle), 15 W (top row), and 50 W (bottom row) [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

TABLE 2.

Size of puncture and penumbra of tissue blanching measured under microscopy comparing radiofrequency-assisted needle and guidewire punctures in different cardiac tissue in freshly explanted pig hearts

| Tissue | Electrified traversals | Mechanical traversals | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Needle electrical, n = 18 | Astato electrical (tip), n = 18 | Needle mechanical, n = 9 | Astato mechanical (back-end), n = 9 | |||||||

| Atrial septum | Hole (mm) | 1.11 ± 0.40 | 0.37 ± 0.08 | P = .009 | 0.63 ± 0.11 | 0.19 ± 0.16 | P = .01 | |||

| Penumbra (mm) | 3.62 ± 1.23 | 0.72 ± 0.29 | P = .003 | Negligible | Negligible | |||||

| Subgroup | ||||||||||

| Needle 50 W, n = 9 | Needle 15W, n = 9 | Astato 50 W, n = 9 | Astato 15 W, n = 9 | |||||||

| Hole (mm) | 0.99 ± 0.38 | 1.24 ± 0.46 | P = .65 | 0.39 ± 0.11 | 0.36 ± 0.05 | P = .80 | ||||

| Penumbra (mm) | 3.68 ± 0.74 | 3.57 ± 1.80 | P = .89 | 0.73 ± 0.22 | 0.70 ± 0.40 | P = .93 | ||||

| Ventricular septum | Hole (mm) | 1.24 ± 0.24 | 0.45 ± 0.05 | P < .001 | 1.07 ± 0.24 | 0.13 ± 0.23 | P = .01 | |||

| Penumbra (mm) | 5.30 ± 1.16 | 0.75 ± 0.20 | P < .001 | Negligible | Negligible | |||||

| Subgroup | ||||||||||

| Needle 50 W, n = 9 | Needle 15W, n = 9 | Astato 50 W, n = 9 | Astato 15 W, n = 9 | |||||||

| Hole (mm) | 1.11 ± 0.24 | 1.37 ± 0.20 | P = .08 | 0.47 ± 0.02 | 0.42 ± 0.06 | P = .38 | ||||

| Penumbra (mm) | 5.82 ± 0.44 | 4.77 ± 1.52 | P = .44 | 0.86 ± 0.15 | 0.63 ± 0.19 | P = .14 | ||||

| Aorta | Hole (mm) | 0.88 ± 0.16 | 0.29 ± 0.12 | P < .001 | 0.70 ± 0.11 | 0.12 ± 0.12 | P = .007 | |||

| Penumbra (mm) | 2.77 ± 1.20 | 0.59 ± 0.15 | P = .005 | Negligible | Negligible | |||||

| Subgroup | ||||||||||

| Needle 50 W, n = 9 | Needle 15W, n = 9 | Astato 50 W, n = 9 | Astato 15 W, n = 9 | |||||||

| Hole (mm) | 0.89 ± 0.15 | 0.87 ± 0.15 | P = .92 | 0.33 ± 0.12 | 0.25 ± 0.12 | P = .35 | ||||

| Penumbra (mm) | 3.12 ± 1.67 | 2.41 ± 0.68 | P = .38 | 0.58 ± 0.17 | 0.60 ± 0.17 | P = .04 | ||||

A P value of <.05 was considered statistically significant.

4 DISCUSSION

Atrial trans-septal crossing may be difficult in patients with thickened fibrous interatrial septa, aneurysmal septa, or previous surgical patch repair [10]. Commercial radiofrequency wires and needles are effective and safe compared with electrifying a Brockenbrough needle [2], but may be limited by availability and cost ($495 for the Baylis NRG needle; $1450 + $180 for the Baylis Nykanen wire and Protrack microcatheter; $19,950 for the Baylis radiofrequency puncture generator; $189 for the SafeSept wire; and $150 for the Astato guidewire). We describe a low-risk adjunct as a simple and effective escalation strategy.

The coronary guidewire, insulated by the trans-septal dilator and sheath, is used to concentrate current at the atrial septal crossing point. When the guidewire is energized, the cells adjacent to its tip vaporize, allowing free passage of the guidewire into the left atrium. The transseptal needle has high conductance and must be sheathed in the dilator when delivering radiofrequency energy through the coronary wire to prevent current dispersal and reduced crossing effectiveness. An unsheathed trans-septal needle may have caused the failed crossing attempt in one patient, where no microbubbles were seen on echocardiography with radiofrequency energy application and electrosurgical crossing needed to be augmented by mechanical cutting using the stiffer, sharper amputated guidewire tip. This modification increases the risk of wire perforation through the left atrial free wall.

Our animal model confirmed proof of concept, demonstrating faster traversal at lower energy compared with an electrified Brockenbrough needle, with decreased puncture size and surrounding tissue damage. Importantly in the case of the needle, the injury extends beyond the 2.6 mm outer diameter of an SL-1 sheath, which may impact tissue recoil and hemostasis.

Further studies need to be performed to establish parameters minimizing this collateral damage in catheter electrosurgery. From the surgical literature, rapid tissue traversal using smaller active electrodes at the minimum power for unimpeded tissue vaporization creates the optimal cut with minimal damage to surrounding tissues [11], though little difference was seen between 15 W and 50 W in this study.

The risk of thrombus formation resulting from radiofrequency energy delivery was mitigated by short duration of energy delivery and systemically anticoagulating before crossing was attempted. The risk of embolization is theoretically greater with an electrified Brockenbrough needle, not only because of tissue coring [6], but also increased duration of energy delivery can cause char and coagulum formation on the electrode tip. Traversal was instantaneous with a guidewire, reducing this risk. This risk may be further mitigated by using lower energy levels. In this case series, 50 W was chosen as this was the energy used clinically for transcaval crossing [12], though our benchtop studies suggest lower power may be reasonable.

The 0.014″ wire alone may not provide sufficient shaft support for the dilator and sheath to cross the septum, so the needle is advanced in tandem with wire, dilator, and sheath for increased shaft support. Alternatively, a balloon septostomy is performed over the wire before advancing the sheath. Finally, we have only tested the utility of transcatheter electrosurgery for trans-septal puncture using the two guidewires mentioned. Other guidewires with different insulation and tip properties may produce different results.

Excimer laser trans-septal puncture is an alternative to radiofrequency assisted puncture and has been described in swine but has not been translated into clinical practice [13]. However, this seems complicated and expensive, compared with our guidewire electrosurgery technique.

5 CONCLUSION

We describe an effective adjunct to trans-septal crossing that may be considered when conventional needle puncture proves difficult or dangerous. We believe this technique to be safer than electrifying a transseptal needle and is widely available to operators. The next step would be to establish safety and efficacy prospectively in a large patient cohort.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Center for Structural Heart Disease, Division of Cardiology, Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, MI, USA, and the Division of Intramural Research (Z01-HL006040), National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, USA.

Funding information

Center for Structural Heart Disease, Division of Cardiology, Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, MI, USA; Division of Intramural Research, National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, USA, Grant/Award Number: Z01-HL006040;

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

ABG serves as a proctor for Edwards Lifesciences and St Jude Medical.

ORCID

Jaffar M. Khan BM, BCh http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6099-0753

Marvin H. Eng MD http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0334-6504

Robert J. Lederman MD http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1202-6673

References

- 1.Justino H, Benson LN, Nykanen DG. Transcatheter creation of an atrial septal defect using radiofrequency perforation. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2001;54:83–87. doi: 10.1002/ccd.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winkle RA, Mead RH, Engel G, Patrawala RA. The use of a radiofrequency needle improves the safety and efficacy of transseptal puncture for atrial fibrillation ablation. Heart Rhythm. 2011;8:1411–1415. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feld GK, Tiongson J, Oshodi G. Particle formation and risk of embolization during transseptal catheterization: Comparison of standard transseptal needles and a new radiofrequency transseptal needle. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2011;30:31–36. doi: 10.1007/s10840-010-9531-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bidart C, Vaseghi M, Cesario DA, Mahajan A, Fujimura O, Boyle NG, et al. Radiofrequency current delivery via transseptal needle to facilitate septal puncture. Heart Rhythm. 2007;4:1573–1576. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maisano F, La Canna G, Latib A, Godino C, Denti P, Buzzatti N, et al. Transseptal access for MitraClip(R) procedures using surgical diathermy under echocardiographic guidance. EuroIntervention. 2012;8:579–586. doi: 10.4244/EIJV8I5A89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenstein E, Passman R, Lin AC, Knight BP. Incidence of tissue coring during transseptal catheterization when using electrocautery and a standard transseptal needle. Circ Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 2012;5:341–344. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.111.968040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Asmundis C, Chierchia GB, Sarkozy A, Paparella G, Roos M, Capulzini L, et al. Novel trans-septal approach using a Safe Sept J-shaped guidewire in difficult left atrial access during atrial fibrillation ablation. Europace Eur Pacing Arrhythmias Cardiac Electrophysiol. 2009;11:657–659. doi: 10.1093/europace/eup089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wadehra V, Buxton AE, Antoniadis AP, McCready JW, Redpath CJ, Segal OR, et al. The use of a novel nitinol guidewire to facilitate transseptal puncture and left atrial catheterization for catheter ablation procedures. Europace. 2011;13:1401–1405. doi: 10.1093/europace/eur155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Santangeli P, Shaw GC, Marchlinski FE. Radiofrequency wire facilitated interventricular septal access for catheter ablation of ventricular tachycardia in a patient with aortic and mitral mechanical valves. Circ Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 2017;10 doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.116.004771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marcus GM, Ren X, Tseng ZH, Badhwar N, Lee BK, Lee RJ, et al. Repeat transseptal catheterization after ablation for atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2007;18:55–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Honig WM. The mechanism of cutting in electrosurgery. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1975;22:58–62. doi: 10.1109/tbme.1975.324541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenbaum AB, O’Neill WW, Paone G, Guerrero ME, Wyman JF, Cooper RL, et al. Caval-aortic access to allow transcatheter aortic valve replacement in otherwise ineligible patients: Initial human experience. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:2795–2804. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elagha AA, Kim AH, Kocaturk O, Lederman RJ. Blunt atrial transseptal puncture using excimer laser in swine. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2007;70:585–590. doi: 10.1002/ccd.21257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]