Abstract

Objectives

The purpose of this study was to evaluate performance on two challenging listening tasks, talker and regional accent discrimination, and to assess variables that could have affected the outcomes.

Study Design

A prospective study using 35 adults with one cochlear implant (CI) or a CI and a contralateral hearing aid (bimodal hearing) was conducted. Adults completed talker and regional accent discrimination tasks.

Methods

Two-alternative forced-choice tasks were used to assess talker and accent discrimination in a group of adults who ranged in age from 30 years old to 81 years old.

Results

A large amount of performance variability was observed across listeners for both discrimination tasks. Three listeners successfully discriminated between talkers for both listening tasks, 14 participants successfully completed one discrimination task and 18 participants were not able to discriminate between talkers for either listening task. Some adults who used bimodal hearing benefitted from the addition of acoustic cues provided through a HA but for others the HA did not help with discrimination abilities. Acoustic speech feature analysis of the test signals indicated that both the talker speaking rate and the fundamental frequency (F0) helped with talker discrimination. For accent discrimination, findings suggested that access to more salient spectral cues was important for better discrimination performance.

Conclusions

The ability to perform challenging discrimination tasks successfully likely involves a number of complex interactions between auditory and non-auditory pre- and post-implant factors. To understand why some adults with CIs perform similarly to adults with normal hearing and others experience difficulty discriminating between talkers, further research will be required with larger populations of adults who use unilateral CIs, bilateral CIs and bimodal hearing.

Keywords: Cochlear Implants, Bimodal Hearing, Speech Discrimination

1. INTRODUCTION

For adults with severe-to-profound deafness, cochlear implants (CIs) have greatly improved their communication abilities (Firszt, Holden, Reeder, Cowdrey, & King, 2012; Gifford, Dorman, Shallop, & Sydlowski, 2010; Zeng, 2004). Some adults who were once incapable of participating in conversations because of their deafness, now achieve up to 100% word and sentence understanding in quiet environments (Gifford et al., 2010; Wilson & Dorman, 2008). However, a large amount of performance variability exists and much more research is needed to more fully appreciate the underlying reasons for poor performance with a CI (Bierer, Spindler, Bierer, & Wright, 2016; Holden et al., 2016; Moberly, Bates, Harris, & Pisoni, 2016). Some adults with CIs perform similarly to adults with normal hearing but others struggle to understand monosyllabic words presented in quiet environments (Bierer et al., 2016; Moberly, Lowenstein, & Nittrouer, 2016). The purpose of this study was to examine performance variability on two challenging listening tasks, talker and accent discrimination, in adults who use one CI or a CI and a contralateral hearing aid (bimodal hearing).

Evidence has suggested that listeners with CIs struggle to perceive spoken language because of the poor spectral resolution that results from the CI speech processing algorithms. That is, the limited number of spectral channels (Nie, Barco, & Zeng, 2006; Xu & Pfingst, 2008), the interactions between the electrodes within the device (Stickney et al., 2006), and the distorted tonotopic map that results from placement of the electrode array within the cochlea (Li & Fu, 2010) all contribute to poorer spectral resolution. Additionally, other data suggest that as spectral information of speech processed through a CI declines, listeners rely more heavily on temporal cues for speech perception (Nie et al., 2006; Schvartz, Chatterjee, & Gordon-Salant, 2008; Xu, Thompson, & Pfingst, 2005).

Others have demonstrated that specific pre-operative auditory and non-auditory factors explain postoperative performance. Specifically, those with longer durations of deafness prior to implantation, age of implantation, and duration of CI use has been shown to explain outcome performance (Blamey et al., 1996; Blamey et al., 2013; Lazard et al., 2012). Recently, however, the duration of deafness prior to implantation has been shown to be less important than it has been in the past most likely due to the relaxed candidacy criteria for those seeking implantation (Blamey et al., 2013). The degree of pre-implant residual hearing has also been shown to be beneficial for post-implant performance. Individuals with a greater degree of residual hearing prior to implantation perform better on a wide range of speech perception tasks compared to individuals with less residual hearing (Francis, Yeagle, Bowditch, & Niparko, 2005; Gantz, Woodworth, Knutson, Abbas, & Tyler, 1993; Gomaa, Rubinstein, Lowder, Tyler, & Gantz, 2003). Researchers also have observed that more low frequency residual hearing prior to implantation is important for post-implantation speech perception (Marx et al., 2015; Mulhern & Cullington, 2014).

Factors affecting performance on listening tasks also include the acoustic properties of the presented stimuli. The fundamental frequency (F0) and the speaking rate of the talker can influence the outcomes. Fuller et al (2013) demonstrated that adults who use cochlear implants relied on talker F0 cues for gender categorization rather than using both F0 and vocal track length (VTL) cues. Listeners with normal hearing use both F0 and VTL for gender categorization. Fu, Chincilla, Nogaki, & Galvin (2005) assessed voice-gender identification in a group of CI and normal hearing listeners using two sets of male and female talker stimuli. One set of talkers had a mean difference in F0 of 100 Hz across talkers and the other group of talkers had a 10 Hz mean difference. It was found that both the normal hearing listeners and CI users had better voice-gender identification when listening to the group of talkers with the 100 Hz separation in F0 compared to the group of talkers with the 10 Hz separation in F0. Additionally, findings have suggested that the speaking rate of the talker will have a dramatic impact on cochlear implant listeners’ spoken word understanding. Ji, Galvin, Xu, and Fu (2013) found that when listening to synthetic speech presented at twice the normal speaking rate, CI listeners’ understanding of IEEE sentences was much poorer than their understanding of the speech presented at a normal speaking rate and at half the normal speaking rate.

For some, the use of a contralateral hearing aid and the access it provides to low-frequency acoustic cues improves word recognition in quiet and in noise, the identification of Mandarin tones and timbre, and music perception (Kong, Cruz, Jones, & Zeng, 2004; Kong, Mullangi, & Marozeau, 2012; Kong, Stickney, & Zeng, 2005; Li, Zhang, Galvin, & Fu, 2014; Yoon, Shin, Gho, & Fu, 2015). Presumably, access to low frequency acoustic cues provided through a hearing aid most likely was helpful for these listening tasks. However, within studies, a large amount of variability is observed with some receiving significant benefit from bimodal hearing and others receiving very little, if any, benefit (Ching, van Wanrooy, & Dillon, 2007; Choi et al., 2016; Incerti, Ching, & Cowan, 2013; Mulhern & Cullington, 2014). Evidence has suggested that those with more residual low-frequency hearing, or pure tone averages for 250 Hz, 500 Hz, and 1000 Hz better than 60 or 70 dB, obtained more bimodal benefit than those with poorer low-frequency residual hearing (Blamey et al., 2015; Choi et al., 2016; Reiss, Eggleston, Walker, & Oh, 2016).

In the present study, we tested a group of listeners who used unilateral cochlear implants and a group who used bimodal hearing on two challenging listening tasks, talker and regional accent discrimination, and assessed variables affecting outcomes. Participants were asked to discriminate between male and female talkers who had general American accents, and additionally, to discriminate between same-gender talker-pairs of sentences with northern American and southern American accents. Understanding challenges that adults with cochlear implants experience may help to improve post-implantation clinical management, perhaps through participating inan individually designed post-implantation rehabilitation programs that focus on the development of specific perception skills, and/or through the use of a contralateral hearing aid.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1 Participants

Data from 35 study participants who participated in an earlier vowel identification study were used for this study (Hay-McCutcheon, Peterson, Rosado, & Pisoni, 2014). All 35 post-lingually deaf adults received a cochlear implant at the Department of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery at the Indiana University School of Medicine. The project was carried out according to basic ethical standards for the protection of human research subjects and was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Indiana University and the University of Alabama. Nineteen of these implanted adults used a hearing aid in the opposite ear. Demographic data for the listeners with unilateral CIs are shown in Table 1 and the data for the listeners using bimodal hearing are provided in Table 2. The pre-implant pure tone average (PTA) at 500 Hz, 1000 Hz, and 2000 Hz in the better hearing ear, the pre-implant low-frequency pure tone average (LF_PTA) at 250 Hz, 500 Hz, and 1000 Hz in the better hearing ear, and the post-implant PTA at 250 Hz, 500 Hz, 1000 Hz, 2000 Hz, 3000 Hz, and 4000 Hz (PTA_CI) are provided in both tables. All participants had at least 6 months of experience with their cochlear implant device prior to testing. The devices were programmed using the current software programming at the time (i.e., SPEAK, ACE, CIS, MPS). All study participants wore their implant for the majority of their waking hours. During testing, the implant was set at their everyday listening/volume settings. All study participants were native-English speakers and the majority of them had lived in Indiana, Illinois or Ohio for most of their lives. Two participants lived in states outside of the North Midland regional area. One lived in Maryland for the majority of his life and the other spent 25 years in both Alabama and West Virginia.

Table 1.

Demographics for unilateral cochlear implant recipients

| Participant ID | Age at testing (yr) | Implant model | Duration of CI use (yr) | Pre-implant PTA (dB HL) | Pre-implant LF-PTA (dB HL) | Sound Field CI PTA (dB HL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAK1 | 52.5 | N24-CI24R (CS) | 3.9 | 112 | 117 | 23 |

| AAN1 | 56.3 | N24-CI24R (CS) | 4.2 | 92 | 92 | 34 |

| AAO1 | 81.8 | ME-Combi 40+ H | 3.0 | 77 | 80 | 21 |

| AAP1 | 48.9 | N22-CI22M | 15.6 | 120 | 120 | 36 |

| AAS1 | 61.1 | ME-Combi 40+ H | 3.5 | 107 | 97 | 22 |

| AAT1 | 77.4 | N24-CI24RE (CA) | 3.8 | 107 | 82 | 24 |

| AAV1 | 55.3 | N24-CI24M | 10.1 | 105 | 83 | NA |

| AAW1 | 66.9 | N24-CI24RE (CA) | 1.2 | 92 | 90 | 30 |

| AAX1 | 30.4 | N24-CI24RE (CA) | 2.1 | 112 | 98 | 21 |

| ABA1 | 59.7 | N24-CI24R (CS) | 5.8 | 87 | 73 | 18 |

| ABD1 | 59.7 | CL-HiRes 90K | 2.9 | 78 | 55 | 32 |

| ABE1 | 48.9 | N24-CI24RE (ST) | 2.5 | 77 | 52 | 21 |

| ABF1 | 48.4 | ME-Combi 40+ H | 4.4 | 80 | 80 | 20 |

| ABI1 | 64.5 | N24-CI24RE (CA) | 2.1 | 110 | 108 | 28 |

| ABS1 | 43.7 | N24-CI24RE (CA) | 2.6 | 100 | 87 | 25 |

| ABU1 | 61.7 | CL-HiRes 90K | 2.9 | 108 | 107 | 28 |

| Mean | 57.3 | 4.4 | 97.4 | 89 | 26 | |

| SD | 12.5 | 3.6 | 14.1 | 19 | 5 |

NOTE: Pre-implant PTA is the average behavioral threshold of 500 Hz, 1000 Hz, and 2000 Hz before implantation in the better hearing ear. Pre-Implant LF-PTA is the average behavioral threshold of 250 Hz, 500 Hz, and 1000 Hz before implantation in the better hearing ear. Sound Field CI PTA is the average behavioral threshold of 250 Hz, 500 Hz, 1000 Hz, 2000 Hz, 3000 Hz, and 4000 Hz after implantation. NA – Not available

Table 2.

Demographic information for adults who used bimodal hearing

| Participant ID | Age at testing(yr) | Implant model | Duration of CI use (yr) | Pre-Implant PTA(dB HL) | Pre-Implant LF- PTA (dB HL) | Sound Field CI PTA (dB HL) | HA model | Duration of HA use (yr) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAD | 72.7 | ME-Combi40+ H | 2.4 | 87 | 62 | 29 | Unitron digital SF | 32 |

| AAG | 54.7 | N24-CI24R(CS) | 4.9 | 105 | 83 | 24 | Unitron US 80-PP | 45 |

| AAM | 58.0 | ME-Combi40+ H | 2.7 | 100 | 82 | 26 | Marcon | 47 |

| AAQ | 68.7 | CL-HiFocus | 7.1 | 95 | 83 | 26 | Widex Senso | 50 |

| AAR | 74.2 | N24-CI24M | 9.2 | 98 | 77 | 35 | Widex Q32 | 22 |

| AAU | 57.6 | N24-CI24RE(CA) | 0.9 | 100 | 88 | 20 | GN Resound 780 D | 49 |

| ABB | 73.5 | ME-Combi40+ HS | 7.2 | 93 | 73 | 33 | Oticon 39 PL | 33 |

| ABC | 70.4 | N24-CI24RE(CA) | 1.2 | 82 | 55 | 30 | Phonak Perseo311 DAZ | 28 |

| ABG | 64.8 | ME-Combi40+ H | 3.1 | 93 | 93 | 28 | Phonak Senso- Forte 331X | 46 |

| ABJ | 70.4 | N24-CI24RE(CA) | 0.5 | 105 | 105 | 27 | Oticon Digifocus II SP | 20 |

| ABK | 73.7 | ME-Combi40+ H | 8.0 | 78 | 72 | 31 | Starkey A575 Sequel AH | 12 |

| ABM | 69.6 | N24-CI24RE(CA) | 2.6 | 88 | 60 | 22 | CN Resound | 39 |

| ABN | 57.7 | CL-HiRes 90K | 2.6 | 92 | 83 | 36 | CN Resound 780 D | 45 |

| ABO | 62.7 | N24-CI24RE(CA) | 1.7 | 108 | 87 | 34 | Siemens Infinity Pro SP | 32 |

| ABQ | 44.8 | N24-CI24RE(CA) | 0.6 | 83 | 73 | 24 | Oticon Digifocus II | 40 |

| ABR | 70.7 | CL-HiRes 90K | 2.3 | 113 | 108 | 25 | AVR XP 675 | 62 |

| ABT | 71.0 | CL-HiRes 90K | 1.2 | 107 | 97 | 29 | Phonak Supero413 AZ | 31 |

| ABV | 54.8 | N24-CI24RE(CA) | 2.1 | 80 | 82 | 30 | Phonak Perseo311 DAZ | 11 |

| ABW | 38.5 | N24-CI24RE(CA) | 0.6 | 95 | 97 | 27.2 | Rexton Energy | 25 |

| Mean | 63.6 | 3.2 | 94.5 | 82 | 27 | 35 | ||

| SD | 10.3 | 2.7 | 10.3 | 14 | 5 | 14 |

NOTE: Pre-Implant PTA is the average behavioral thresholds of 500 Hz, 1000 Hz, and 2000 Hz before implantation in the better hearing ear. Pre-Implant LF-PTA is the average behavioral thresholds of 250 H, 500 Hz, and 1000 Hz before implantation in the better hearing ear. Sound Field CI PTA is the average behavioral thresholds of 250 Hz, 500 Hz, 1000 Hz, 2000 Hz, 3000 Hz, and 4000 Hz after implantation.

2.2 Stimuli and Procedures

2.2.1 Talker Discrimination

Talker discrimination was assessed using the stimulus materials developed by Kirk, Houston, Pisoni, Sprunger, & Kim-Lee (2002). Two sentences were selected from the digital database developed and maintained by the Speech Research Laboratory at Indiana University. These sentences were drawn from recordings of 100 Harvard IEEE sentences produced by five female and five male talkers. For purposes of this study, four female and four male talkers were selected. They were between the ages of 25 and 40 years old. These talkers spoke with a general American dialect and were selected to maximize the fundamental frequency (F0) range within both genders. The first sentence presented during the task was “He ran half way to the hardware store” which was always followed by “Mesh wire keeps chicks inside.” Each trial was 1000 ms in duration and the presentation of each sentence within a trial was separated by a 300 ms inter-stimulus interval. During the task, the sentence-pairs were presented at 65 dB SPL via two Advent AV570 speakers placed at 45º azimuth. Study participants were required to determine whether the two sentences were spoken by the same talker or two different talkers. After listening to each pair of sentences, the participant selected one of two squares on a computer screen indicating whether the sentences were spoken by the same or different talkers. With eight talkers, there were a total of 56 two-talker combinations of different talkers (i.e., each talker paired with 7 different talkers). All 56 of these combinations were presented. Additionally, 56 trials were also presented in which the same talker produced both sentences. Consequently, a total of 112 trials in this task were presented with half of the trials being same-talker stimuli and half of them consisting of two different talkers. The order of the trials was randomized. Raw percentage scores and d-prime discriminability scores for each participant were obtained. D-prime scores were calculated using the hit rates and the false alarm rates as outlined in Macmillan and Creelman (2005).

2.2.2 Regional Accent Discrimination

The stimuli used for the regional accent discrimination task came from the Texas Instruments/Massachusetts Institute of Technology (TIMIT) database (Fisher, Doddington, & Goudie-Marshall, 1986). The TIMIT corpus consists of 630 talkers representing seven geographical regions of the United States, and includes 2,342 different sentences. For purposes of this test, 16 novel sentences produced by four male and four female talkers from either the northern or southern regions of the United States (i.e., 16 talkers in total) were used to measure accent discrimination (see Appendix A). Talkers were between the ages of 20 and 29 years old. Each talker was paired with another talker seven times for a total of 56 trials. The same talkers were not paired together in any given trial. The listener heard two talkers on each trial, both originating from the South, both from the North region, or one from the South and one from the North. Within each trial the gender of the talker was always held constant. The listener’s task was to determine if the pair of sentences was spoken by talkers of the same or different regions (i.e., north or south) and then select the appropriate response option on a computer monitor. Listeners were seated in a sound booth and stimuli were presented at 65 dB SPL through two Advent AV570 speakers placed at 45º azimuth. Raw percentage correct and d-prime values were calculated for each participant’s responses.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Device Group Comparison

It is possible that individuals who used bimodal hearing were able to take advantage of additional acoustic cues provided through a hearing aid because they had more residual hearing both before and after implantation. Individuals who used contralateral hearing aids with their cochlear implants might have performed better simply because they had more useable hearing at the time of testing. To ensure that there were no significant differences in pre- and post-implantation residual hearing between groups, two ANOVAs were conducted using the pre-implant PTA and the post-implant PTA_CI. No significant differences were found between the CI-only group and the bimodal hearing group for pre-implant residual hearing [F(1, 34) = 0.51, p = 0.48] and post-implant residual hearing [F(1, 33) = 2.46, p = 0.12].

3.2 Talker Discrimination

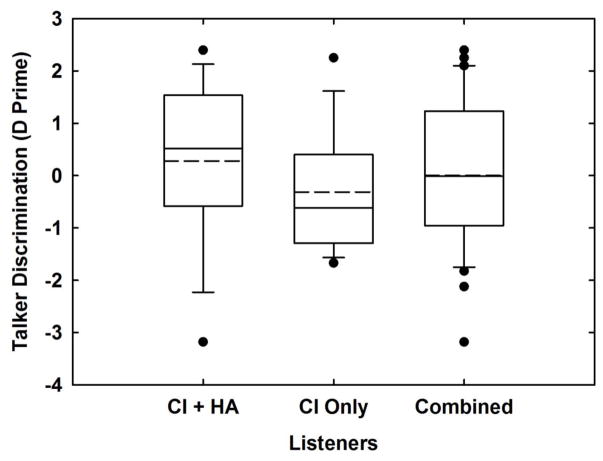

To effectively control for individual response biases when performing a same-different forced choice listening task, signal detection theory was used to generate d-prime discriminability scores for the overall performance on this task (Macmillan & Creelman, 2005). A measure of listening sensitivity, d-prime, was calculated using the number of hits (i.e., correctly identified responses) and false alarms (i.e., 1 – the number of correct rejections). The higher the d-prime value the better the discrimination performance. The results of this analysis for the talker discrimination task are shown in Figure 1. One study participant, ABV, did not complete this task. In all the figures that follow, the horizontal edges of each box represent the 25th and 75th percentiles, the solid line within the box represents the median and the dotted line represents the mean. The whiskers represent the 10th and 90th percentiles and the solid circles show the suspected outliers.

Figure 1.

D-prime results for the talker discrimination task are shown in this figure. The horizontal edges of each box represent the 25th and 75th percentiles, the solid line within the box represents the median and the dotted line represents the mean. The whiskers represent the 10th and 90th percentiles and the solid circles show the suspected outliers. The outcomes for all of the participants are shown in the far right box, the results for the participants who used one cochlear implant are provided in the center, and finally, the outcomes from the participants who used bimodal hearing are provided in the left box plot.

As shown in Figure 1, we found a great deal of variability in the results with some participants performing well and others demonstrating poor performance on this task. The median and mean d-prime values for the bimodal hearing group were 0.52 and 0.28, respectively. The median and mean d-prime values for the CI-only group were −0.62 and −0.31, respectively. This was a challenging task for the majority of the listeners. Due to the inability of the majority of the participants to successfully perform this task or the regional accent discrimination task described below, statistical analyses would not provide meaningful revelations.

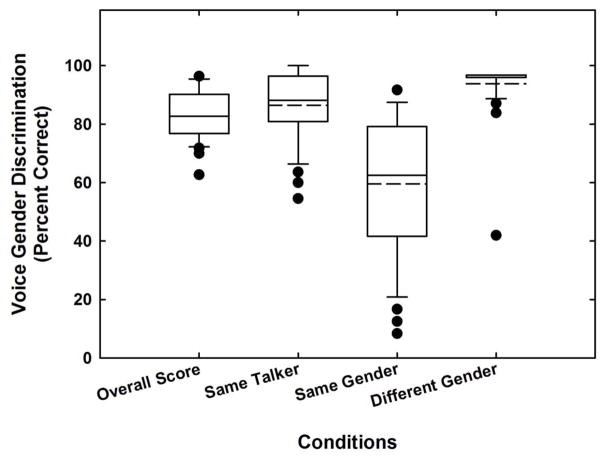

To assess the more challenging listening conditions for this discrimination task, performance for each talker condition was calculated separately. The results are presented in Figure 2. Specifically, the overall percent correct (i.e., 82.7%) for this task is provided on the far left, and each of the remaining plots display the percent correct for the listening conditions when both sentences were spoken by the same talker, by talkers of the same gender, and by talkers of different genders. The mean scores for the same talker condition (i.e., 86.4%) and the different gender condition (i.e., 93.8 % correct) suggest that individuals with cochlear implants can discriminate differences between two sentences from the same talker and two talkers of different genders. However, listeners had much more difficulty discriminating between two talkers of the same gender as indicated in the mean score for that condition (i.e., 59.6% correct). Consequently, a listener error analysis was conducted to explore potential difficult discrimination tasks.

Figure 2.

Outcomes from the talker discrimination task are displayed in this figure. The overall percent correct is provided on the far left, and each of the remaining plots display the percent correct for the listening condition when both sentences were spoken by the same talker, by talkers of the same gender, and by talkers of different genders. The horizontal edges of each box represent the 25th and 75th percentiles, the solid line within the box represents the median and the dotted line represents the mean. The whiskers represent the 10th and 90th percentiles and the solid circles show the suspected outliers.

3.2.1 Listener Error Analysis

The poorest performance for the talker discrimination task occurred when listeners were presented with two different talkers of the same gender, and consequently, these errors were examined more closely to explore outcome trends. The overall proportion of these errors are presented in Table 3. For this listening condition, when the four female and four males were paired with each same-gender talker, only one presentation for each talker pair occurred (i.e., 12 presentations for the entire listening task). The mean proportions were determined by summing the errors made by the all of the listeners for each talker-pair presentation and then dividing that number by the total number of presentations (i.e., 34 listeners for the entire sample). The proportion of errors that were made when listening to the female talker-pairs are presented in the top matrix and the errors that were made when listening to the male talker-pairs are presented in the bottom matrix. For the female talker presentations, the fewest number of errors were made when Female 1 (F1) who presented Sentence 1 (S1) (“He ran halfway to the hardware store”) was paired with F3 presenting Sentence 2 (S2) (“Mesh wire keep chicks inside”) (i.e., 0.21). For the male talker presentation, the fewest number of errors occurred when M3S1 was paired with either M1S2 (i.e., 0.15) or M2S2 (i.e., 0.15). Due to the limited number of vowel and consonant utterances for each of these talkers, we were not able to perform meaningful formant frequency analyses that might help determine the underlying reasons for our findings. However, we were able to examine speaking rates and F0 values for these talkers and these data are presented in Table 4.

Table 3.

Proportion of listener errors for talker discrimination task

| Female Talkers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Talker ID | F1S2 | F2S2 | F3S2 | F4S2 |

| F1S1 | 0.44 | 0.32 | NA | |

| F2S1 | 0.47 |

|

0.56 | |

| F3S1 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.82 | |

| F4S1 | 0.44 | 0.56 | 0.35 | |

| Male Talkers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Talker ID | M1S2 | M2S2 | M3S2 | M4S2 |

| M1S1 | 0.32 | 0.18 | 0.44 | |

| M2S1 | 0.56 | 0.18 | 0.32 | |

| M3S1 |

|

|

0.53 | |

| M4S1 | 0.35 | 0.21 | 0.65 | |

NOTE: S1 is “He ran halfway to the hardware store,” and S2 is “Mesh wires keep chicks inside.” Outlined proportion values indicate the best performance for the female (F) and male (M) talker-pairs.

Table 4.

Talker speech features for talker discrimination task.

| Talker ID | Speaking Rate(syllables/s) | Mean F0(Hz) | F0 range (Hz) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female Talkers | |||

| F1S1 | 5.44 | 183.37 | 125 – 231 (106) |

| F1S2 | 3.19 | 176.32 | 93 – 222 (129) |

| F2S1 | 2.68 | 215.26 | 160 – 272 (112) |

| F2S2 | 2.40 | 211.34 | 75 – 256 (181) |

| F3S1 | 4.80 | 202.62 | 83 – 264 (181) |

| F3S2 | 2.91 | 211.06 | 171 – 293 (122) |

| F4S1 | 4.70 | 231.89 | 86 – 318 (232) |

| F4S2 | 3.49 | 221.54 | 78 – 291 (213) |

| Male Talkers | |||

| M1S1 | 4.90 | 103.80 | 76 – 141 (65) |

| M1S2 | 3.29 | 105.21 | 79 – 154 (75) |

| M2S1 | 3.96 | 97.65 | 80 – 114 (34) |

| M2S2 | 2.53 | 95.72 | 78 – 118 (40) |

| M3S1 | 5.33 | 140.63 | 101 – 176 (75) |

| M3S2 | 3.14 | 145.38 | 113 – 195 (82) |

| M4S1 | 4.40 | 124.66 | 75 – 164 (89) |

| M4S2 | 2.70 | 119.51 | 76 – 150 (74) |

NOTE: Sentence 1 (S1) is “He ran halfway to the hardware store; Sentence 2 (S2) is “Mesh wire keeps chicks inside.” F = female talker; M = male talker

Examination of both the speaking rates and the F0 for the female and male talkers provides some insight into our findings. Specifically, good performance was found when F2S1 was paired with F3S2 and this finding could have occurred because both of these talkers had slow speaking rates (i.e., 2.68 syllables/s and 2.91 syllables/s). In fact, these two speakers had the slowest speaking rates of the four female talkers. It might have been possible that these slower rates allowed the listeners to more easily discriminate between these two talkers. This pattern though was not observed for the male talker pairs (i.e., when M3S1 was paired with M1S2 or M2S2). The speaking rate of M3S1 was 5.33 syllables/s, for M1S2 it was 3.29 syllables/s and for M2S2 it was 2.53 syllables/s. Possibly, the fast speaking rate of M3S1 (the fastest in the group of male talkers) was a cue for the difference in these talker-pairs. However, when M3S1 was paired with M4S2 (i.e., 2.70 syllables/s) the poorest performance resulted (i.e., 0.53 proportion of errors). Alternatively, differences in F0 might help to explain performance when the male talkers were paired with each other. The F0 for M3S1 was 140 Hz (the highest F0 in the group of male talkers), which might have been a reliable cue for listeners during the presentation of some talker-pairs. When M3S1 was paired with M1S2 (F0 = 105 Hz) and M2S2 (F0 = 95 Hz) the best performance occurred. Both M1 and M2 had the lowest F0 values in the group of male talkers. Possibly, the difference in F0 between M3, M1 and M2 was the cue that aided with discrimination performance.

Although the majority of listeners had difficulty, there were some adults who successfully performed this discrimination task. The d-prime values for these listeners approached an overall score of 1 or were greater than 1. Their results, along with the results from the adults who obtained d-prime scores below 1, are provided in Table 5. When considering the findings for the pairing of female talkers, the greatest number of errors were made when F4S2 was paired with F3S1 (i.e., 0.82 errors shown in Table 3). Both of these talkers had relatively fast speaking rates and high F0 values compared to the group of talkers as a whole, which could have contributed to the poor discrimination performance by the listeners. There were five listeners though who successfully discriminated between these two talkers, AAM, ABM, ABW, ABF and AAG and also performed well on this discrimination task (see Table 5). When the male talkers were paired, the greatest number of discrimination errors occurred when talker M3S2 was paired with talker M4S1 (i.e., 0.65 errors shown in Table 3). Again, compared to the group of talkers, these two sentences were presented using relatively quick speaking rates and higher F0 values. Four of the talkers who performed well on this task, ABM, ABW, ABF and AAU successfully discriminated between these two talkers.

Table 5.

Individual listener d-prime performance and pre- and post-operative variables.

| Performed Well on Both Tasks | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Listener | Device/s | Age(yrs) | CI Use(yrs) | PTA(dB HL) | LF-PTA(dB HL) | LF2-PTA(dB HL) | d’ TD | d’ AD |

| AAM | CI+HA | 58.0 | 2.7 | 98 | 82 | 70 | 2.1 | 1.4 |

| ABM | CI+HA | 69.6 | 2.6 | 88 | 60 | 38 | 2.4 | 1.5 |

| ABW | CI+HA | 38.5 | 0.6 | 95 | 97 | 100 | 0.9 | 1.3 |

| Performed Well on One Task | ||||||||

| ABV | CI+HA | 54.8 | 2.1 | 80 | 82 | 80 | NA | 4.8 |

| ABF | Unilateral CI | 48.4 | 4.4 | 80 | 80 | 78 | 2.3 | 0.1 |

| AAG | CI+HA | 54.7 | 4.9 | 100 | 83 | 70 | 2.1 | NA |

| ABQ | CI+HA | 44.8 | 0.6 | 83 | 73 | 70 | 1.6 | 0.1 |

| AAR | CI+HA | 74.2 | 9.2 | 97 | 77 | 60 | 1.5 | −0.4 |

| AAU | CI+HA | 57.6 | 0.9 | 100 | 88 | 80 | 1.3 | −1.4 |

| ABE | Unilateral CI | 48.9 | 2.5 | 77 | 52 | 33 | 1.3 | 0.5 |

| ABK | CI+HA | 73.7 | 8.0 | 78 | 72 | 68 | 1.2 | −1.1 |

| ABC | CI+HA | 70.4 | 1.2 | 78 | 55 | 45 | 0.4 | 1.8 |

| ABA | Unilateral CI | 59.7 | 5.8 | 83 | 73 | 65 | 0.4 | 1.8 |

| AAX | Unilateral CI | 30.4 | 2.1 | 108 | 98 | 88 | 0.4 | 0.8 |

| ABN | CI+HA | 57.7 | 2.6 | 92 | 83 | 85 | −0.3 | 2.5 |

| ABI | Unilateral CI | 64.5 | 2.1 | 110 | 108 | 105 | −1.1 | 1.0 |

| AAQ | CI+HA | 68.7 | 7.1 | 100 | 83 | 73 | −3.2 | 1.0 |

| Did Not Perform Well on Either Task | ||||||||

| AAD | CI+HA | 72.7 | 2.4 | 85 | 62 | 50 | 0.6 | −1.0 |

| AAV | Unilateral CI | 55.3 | 10.1 | 105 | 83 | 73 | 0.3 | 0.13 |

| AAN | Unilateral CI | 56.3 | 4.2 | 92 | 92 | 90 | 0.1 | −0.7 |

| AAT | Unilateral CI | 77.4 | 3.8 | 105 | 82 | 68 | 0.0 | −0.8 |

| ABB | CI+HA | 73.5 | 7.2 | 93 | 73 | 68 | 0.0 | −1.3 |

| ABR | CI+HA | 70.7 | 2.3 | 113 | 108 | 105 | −0.3 | −1.0 |

| ABO | CI+HA | 62.7 | 1.7 | 108 | 87 | 70 | −0.5 | −1.0 |

| AAK | Unilateral CI | 52.5 | 3.9 | 112 | 117 | 110 | −0.6 | −1.5 |

| AAW | Unilateral CI | 66.9 | 1.2 | 92 | 90 | 93 | −0.6 | −1.1 |

| AAO | Unilateral CI | 81.8 | 3.0 | 77 | 80 | 80 | −0.8 | −1.8 |

| ABS | Unilateral CI | 43.7 | 2.6 | 100 | 87 | 80 | −0.9 | 0.2 |

| ABJ | CI+HA | 70.4 | 0.5 | 105 | 105 | 105 | −0.9 | 0.0 |

| AAP | Unilateral CI | 48.9 | 15.6 | 120 | 120 | 120 | −1.4 | −1.6 |

| ABD | Unilateral CI | 59.7 | 2.9 | 82 | 55 | 43 | −1.4 | −1.2 |

| AAS | Unilateral CI | 61.1 | 3.5 | 107 | 97 | 85 | −1.5 | −0.4 |

| ABU | Unilateral CI | 61.7 | 2.9 | 108 | 107 | 105 | −1.7 | −1.9 |

| ABG | CI+HA | 64.8 | 3.1 | 93 | 93 | 93 | −1.8 | 0.0 |

| ABT | CI+HA | 71.0 | 1.2 | 107 | 97 | 88 | −2.1 | −1.0 |

NOTE: PTA – pre-implant pure tone average of 500 Hz, 1000 Hz and 2000 Hz; LF-PTA – pre-implant pure tone average of 250 Hz, 500Hz and 1000 Hz; LF2-PTA – pre-implant pure tone average of 250 Hz and 500 Hz; d’ TD – d-prime for the talker discrimination task; d’ AD – d-prime for the accent discrimination task

3.3 Accent Discrimination

Figure 3 shows the d-prime values for the accent discrimination task. The results for the adults who used bimodal hearing and a unilateral CI are displayed separately from the results for the total group of study participants. Study participant AAG did not complete this task. The median and mean d-prime values for the adults who used bimodal hearing were 0 and 0.35, respectively. The median and mean d-prime scores for the group of adults who used one CI were −0.52 and −0.40. Individual performance is shown in Table 5. These results suggest that this listening task was much more challenging than the talker discrimination task. As with the talker discrimination results, there was a great deal of variability with some participants performing well (i.e., d-prime values approaching or above 1) and others not able to do this discrimination task.

Figure 3.

The d-prime results for the accent discrimination task are presented. The results for the adults who used bimodal hearing are provided on the left, the center box shows the results for the adults who used one CI and the results for all study participants are provided in the right box plot. The horizontal edges of each box represent the 25th and 75th percentiles, the solid line within the box represents the median and the dotted line represents the mean. The whiskers represent the 10th and 90th percentiles and the solid circles show the suspected outliers.

The findings from the individual listening trials for the accent discrimination task are shown in Figure 4. The overall performance is displayed along with the performance when northern and southern talkers were paired, when both talkers were northern speakers, and when both talkers were southern speakers. The overall mean performance on this task was 58.3%. The best performance was found when both talkers were from the northern region of the United States (i.e., mean = 70.6% correct).

Figure 4.

Percent correct outcomes from the accent discrimination task are presented in this figure. The horizontal edges of each box represent the 25th and 75th percentiles, the solid line within the box represents the median and the dotted line represents the mean. The whiskers represent the 10th and 90th percentiles and the solid circles show the suspected outliers. Within the figure, the overall performance is shown along with the performance when northern and southern talkers were paired, when both talkers were northern, and when both talkers were southern.

3.3.1 Listener Error Analysis

Table 6 shows the proportion of errors that were made when listeners discriminated between northern and southern talkers. Each same-gender talker pair was presented once during the listening task, and therefore, each incorrect response was summed for all of the listeners for each talker-pair presentation. These values were then divided by the total number of listeners for each talker-pair (i.e., 34). The proportion of errors made when discriminating between female talkers are presented in the top matrix and the errors made when discriminating between the male talkers are presented in the bottom matrix. For the female talkers, the fewest number of errors were made when NF3 and SF4 were paired (i.e., 0.11). The fewest number of errors for the male talkers were observed when SM4 was paired with NM2 (i.e., 0.18).

Table 6.

Proportion of listener errors for accent discrimination task

| Male Talkers | SM1 | SM2 | SM3 | SM4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NM1 | 0.38 | 0.5 | 0.38 | 0.35 |

| NM2 | 0.35 | 0.21 | 0.53 |

|

| NM3 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.68 | 0.26 |

| NM4 | 0.44 | 0.38 | 0.62 | 0.38 |

| Female Talkers | SF1 | SF2 | SF3 | SF4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NF1 | 0.62 | 0.44 | 0.26 | 0.26 |

| NF2 | 0.68 | 0.5 | 0.44 | 0.47 |

| NF3 | 0.50 | 0.38 | 0.15 |

|

| NF4 | 0.68 | 0.5 | 0.32 | 0.35 |

NOTE: NF is a female talker from the north region and SF is a female talker from the south. NM is a male talker from the north and SM is a male talker from the south. Outlined proportion values indicate best performance for the female talker pairs and the male talker pairs.

As with the talker discrimination task, we calculated the speaking rate and performed pitch analyses to determine if there were identifiable patterns that would explain why some northern and southern talker pairs were easier to discriminate than others. These results are presented in Table 7. Comparison of the speech features for NF3 and SF4 (the best performance for the female talker pairs) suggests that listeners successfully discriminated between these northern and southern talkers partly because of the differences in F0. The F0 for talker NF3 was 202 Hz, the highest F0 of the group of northern female talkers, and the F0 for talker SF4 was 184 Hz, or the lowest F0 of the group of southern talkers. Possibly, listeners used this cue to assist with regional accent discrimination. However, when considering poor performance this trend was not confirmed. That is, the worst performance on this task was observed when SF1 was paired with the other four northern female talkers. SF1 did not have the fastest speaking rate or the highest F0 value of the group of talker-pairs. For the 10 listeners who did well on this task (see Table 5), eight of them performed well when SF1 was paired with NF2 but only four of them correctly discriminated between SF1 and NF4.

Table 7.

Speech features for northern and southern talkers

| Northern Talkers | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Talker ID | Speaking Rate(syllables/s) | F0 range (Hz) | Mean F0 (Hz) |

| NF1 | 5.68 | 81 – 267 (186) | 188.45 |

| NF2 | 4.76 | 75 – 263 (188) | 194.85 |

| NF3 | 4.99 | 162 – 295 (133) | 202.33 |

| NF4 | 4.16 | 131 – 248 (117) | 192.40 |

| NM1 | 4.11 | 117 – 199 (82) | 153.78 |

| NM2 | 4.62 | 89 – 140 (51) | 111.60 |

| NM3 | 3.66 | 90 – 140 (50) | 109.13 |

| NM4 | 5.97 | 74 – 162 (88) | 105.60 |

| Southern Talkers | |||

| SF1 | 3.86 | 154 – 269 (115) | 205.35 |

| SF2 | 4.83 | 69 – 316 (247) | 227.55 |

| SF3 | 4.84 | 195 – 289 (94) | 237.43 |

| SF4 | 4.46 | 87 – 240 (153) | 184.35 |

| SM1 | 4.51 | 93 – 145 (52) | 123.15 |

| SM2 | 3.45 | 52 – 191 (139) | 129.39 |

| SM3 | 3.44 | 54 – 478 (424) | 133.95 |

| SM4 | 5.05 | 98 – 158 (60) | 118.25 |

NOTE: NF is a female talker from the north, NM is a male talker from the north, SF is a female talker from the south, and SM is a male talker from the south.

Possible explanations for the outcomes observed when listeners discriminated between male northern and southern talkers is not as clear. Talker SM4 had the fastest speaking rate and the lowest F0 of the group of southern male talkers. When he was paired with NM2 the least number of listener errors occurred. NM2 did not have the slowest speaking rate or the lowest F0 of the group of northern talkers. In addition, particularly poor performance on this task occurred when SM3 was paired with other northern male talkers. In fact, of the 10 adults who performed well on this task (see Table 5) roughly half of them successfully discriminated between this talker and the others. Only one listener, ABV, successfully discriminated between SM3 and the other northern talkers. SM3 did not have the fastest speaking rate or the highest F0 of all of the southern or northern talkers. He did though have the largest range of F0. Consequently, the explanations for the outcomes using speaking rate and F0 as indicators of performance when listening to male talkers were not definitive.

It might have been possible that listeners were using distinct idiosyncratic acoustic-phonetic talker characteristics to assist with accent discrimination. Specifically, Clopper and Pisoni (2004) and Clopper, Pisoni, and de Jong (2005) demonstrated that vowels produced by northern and southern talkers have consistent acoustic-phonetic features that are discriminable by listeners with normal hearing. The significant regional accent discriminable features for northern and southern talkers are provided in Table 8. These vowel features were used to determine potential cues that our listeners may have used to accurately discriminate between northern and southern talkers.

Table 8.

Significant predictors for the discrimination of northern and southern talkers adapted from Clopper & Pisoni (2004) and Clopper, Pisoni, & de Jong (2005).

| Region | Significant Speech Variables |

| North | /oʊ / offglide centralization |

| /u/ backing | |

| /ɑ/ fronting | |

| South | /oɪ / monophthongization |

| peripheral /oʊ/ offglide | |

| /u/ fronting | |

| /oʊ/ backing | |

| /æ/ diphthongization |

As mentioned above, talker SF4 and NF3 had the fewest number of listener discrimination errors. Talker SF4 (“Toss a die until an ace appears”) had three samples of /æ/ diphthongization. This vowel feature is one used by listeners with normal hearing to identify a southern talker (see Table 8). For the northern talker, NF3, the token sentence had two examples of distinct /u/ backing (“you” and “removal”) and one /ɑ/ fronting (“policy”). Possibly, the number of distinctly southern and northern vowel examples allowed listeners to more easily discriminate these two regional accents. Conversely, poor discrimination occurred when SF1 (“The blue rug was suspiciously bright and new”) was paired with NF4 (“The surplus shoes were sold at a discount price”). Perhaps, the samples of distinctive southern or northern speech cues within the sentences spoken by SF1 and NF4 were too subtle for listeners to discriminate between these northern and southern accents. Specifically, /u/ backing in “shoes” (a distinctive northern cue) and /u/ fronting in “blue” and “new” (a distinctive southern cue) might not have provided sufficient spectral information for accent discrimination purposes. In fact, of all the listeners who performed well on this task (see Table 5), only four of them correctly discriminated between these two talkers, ABV, ABN, AAQ and ABC. It is possible that listeners with CIs required more salient accented tokens to successfully discriminate between southern and northern talkers.

3.4 Individual Variability

The performance variability outcomes are displayed in Table 5. Three adults successfully completed both the talker and accent discrimination task (i.e., excellent performance), 14 adults successfully completed either the talker or the accent discrimination task (i.e., good performance), and 18 adults did not do well on either discrimination task (i.e., poor performance). Also provided in Table 5 is the test age, the duration of CI use, the PTA, the LF-PTA, and the low frequency pre-implant pure tone average at 250 Hz and 500 Hz (LF2-PTA). A one-way ANOVA revealed no significant differences between groups for each of these variables. Due to the limited number of participants in the group who performed well on both tasks, the outcomes should be viewed cautiously.

Although no statistically significant differences between the participant groups was indicated, general observations can be made. All three adults who performed well on both listening tasks (i.e., excellent performers) used bimodal hearing. They ranged in age from 38 to 69 years old, their CI-use ranged from less than one year to over two years, their LF-PTA ranged from 60 dB HL to 97 dB HL and their LF2-PTA ranged from 38 dB HL to 100 dB HL. Nine of the 14 adults who performed well on one listening task (i.e., good performers) used bimodal hearing, they ranged in age from 30 to 74 years old, their CI-use ranged from one year to eight years, their LF-PTA ranged from 55 dB HL to 108 dB HL and their LF2-PTA ranged from 33 dB HL to 105 dB HL. Seven of the 18 adults who did not perform well on either task (i.e., poor performers) used bimodal hearing, they ranged in age from 43 to 77 years old, their CI-use ranged from one to 15 years, their LF-PTA ranged from 55 dB to 120 dB HL, and their LF2-PTA ranged from 43 dB HL to 120 dB HL. In general, therefore, some adults who used bimodal hearing in this study did quite well on challenging listening tasks but others who used bimodal hearing with pre-implant low-frequency hearing (i.e., LF2-PTA and LF-PTA < 60 dB HL or 70 dB HL, respectively) did not do well on either listening task (e.g., AAD and ABB). In addition, one of the excellent performers had pre-implant low-frequency hearing much greater than 60 dB HL (i.e., LF-PTA at 97 dB HL and LF2-PTA at 100 dB HL) but very successfully performed both discrimination tasks.

4. DISCUSSION

The outcomes from the talker and accent discrimination tasks were highly variable with some participants performing quite well on both tasks and others struggling to perform either task successfully. For some, the use of bimodal hearing appeared to have helped with their discrimination abilities, but for others the use of a contralateral HA did not help. The poorest performance on the talker discrimination task occurred when both talkers were of the same gender, and the poorest performance on the accent discrimination task occurred when northern and southern talkers were paired. For the talker discrimination task, our results suggested that listeners used available salient cues (i.e., F0 and speaking rate) to assist with talker discrimination but consistent salient cue patterns were not apparent. For the accent discrimination task, general patterns of F0 and speaking rate cues were not found. It might have been possible for this task that listeners used distinct idiosyncratic acoustic-phonetic regional accent features, such as / æ / diphthongization (a southern talker cue), /u/ backing and /ɑ/ fronting (northern talker cues) for accent discrimination.

4.1 Pre-Implant Low-Frequency Residual Hearing and Bimodal Hearing for Talker and Regional Accent Discrimination

Previous research has suggested that low frequency pre-implant residual hearing is important for successful use of a contralateral hearing aid. Those who have pre-implant low-frequency pure tone averages less than 60 dB HL for 250 Hz and 500 Hz or less than 70 dB HL for 250 Hz, 500 Hz and 1000 Hz typically have better speech perception outcomes than those with poorer low-frequency hearing (Choi et al., 2016; Reiss et al., 2016). Although our findings suggested that LF2-PTAs less than 60 dB HL did help with either talker or accent discrimination for three participants who used bimodal hearing (i.e., ABM, AAR and ABC) all of the other listeners who performed well on at least one task and used bimodal hearing had LF2-PTAs greater than 60 dB HL. In addition, one participant, AAD, with good low-frequency hearing who used a contralateral HA did not perform well on either listening task. Typically though, results from within-subject design studies have suggested that better aided PTA results in improved bimodal benefit, (Illg, Bojanowicz, Lesinski-Schiedat, Lenarz, & Buchner, 2014; Marx et al., 2015; Mulhern & Cullington, 2014; Yoon, Li, & Fu, 2012; Yoon et al., 2015).

The findings in the current study could have been the result of the degree of difficulty of the listening tasks. It is possible that the discrimination tasks were just too challenging to assess accurately the importance of bimodal hearing. The degree of difficulty and the floor effects associated with each listening task could have had an impact on the ability to measure effectively the benefit that might result when using bimodal hearing.

4.2 Acoustic Speech Features and Discrimination Skills

An analysis of the errors listeners made when discriminating between talkers for both listening tasks suggested that adults with CIs use salient speech cues to assist with performance. That is, for the talker discrimination task, listeners most likely used both speaking rate cues and F0 to assist with talker discrimination. For one talker-pair condition, talkers with slow speaking rates were more easily discriminated. Although there is no evidence suggesting that slower speaking rates assist with talker discrimination in adults with CIs, speaking rate has been shown to affect speech recognition performance. Ji et al. (2013) found that speech recognition in adults with CIs was much poorer when they listened to fast speech than when they listened to speech at a normal rate or at a slower rate. In addition, Li et al. (2011) found that Mandarin speaking adults who used CIs had better speech recognition when listening to sentences presented at slow or normal speaking rates compared to their performance when listening to sentences produced at a fast rate.

Additionally, we also found that F0 differences in the talker-pairs might have influenced listener discrimination abilities. For specific talker-pairs with different F0 values, discrimination skills were better than when discriminating between talkers with similar F0 values. Previous evidence has demonstrated that access to F0 cues are important for speech understanding and talker identification in adults with CIs (Brown & Bacon, 2009; Krull, Luo, & Iler Kirk, 2012). Access to different low-frequency F0 cues between the two talkers might have aided with discrimination.

Our data also suggest that salient pitch and acoustic vowel cues may be important for regional accent discrimination. Specifically, listeners made the fewest errors when discriminating between a female southern talker with a relatively low F0, compared to other talkers in the group, and who produced distinctive southern vowel tokens (i.e., / æ / diphthongization). Perhaps, the combination of F0 and acoustic-phonetic cues allowed listeners to more easily discriminate regional southern and northern accents when listening to this talker. Further research will be needed to more fully understand how adults with CIs process these regional accent cues.

4.3 Potential Neurocognitive Factors to Explain Performance Variability

Pre-implant factors such as duration of hearing loss prior to implantation, age at implantation and duration of CI use have been shown to explain a significant portion of performance variability (Blamey et al., 1996; Blamey et al., 2013). Although more recently, evidence has suggested that the duration of hearing loss prior to implantation to account for performance outcomes has become less important (Blamey et al., 2013; Holden et al., 2016). For this study, the duration of hearing loss prior to implantation for participants was not available, and consequently, could not be evaluated.

More recently, there has been an increased interest in using non-auditory cognitive factors to help explain performance variability across CI recipients. The contribution of other non-auditory factors, such as verbal learning and memory, to explain performance variability have been examined (Heydebrand, Hale, Potts, Gotter, & Skinner, 2007; Pisoni et al., in press) Heydebrand et al. (2007) demonstrated that pre-implant verbal learning assessed using the California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT) accounted for 42% of the variability post-implant word recognition testing. Using a group of experienced CI listeners, Pisoni et al (in press) demonstrated that performance on the CVLT was as good as older adults with normal hearing. Their word recall pattern though varied from those of the older adults with normal hearing. The adults with cochlear implants had more difficulty recalling more recently presented words compared to the older adults with normal hearing suggesting that maintaining items in short-term memory could be compromised in this population. Additionally, statistical modeling revealed that when neurocognitive outcomes were combined with conventional demographics and hearing history factors, increased predictive power helping to explain performance resulted (Pisoni et al in press).

For more challenging listening and discriminating tasks as presented in this study, therefore, it might be possible that pre- and post-implantation performance on verbal learning and memory tasks could explain a significant degree of variability. As discussed in Pisoni et al (in press), the use of cognitive factors in combination with auditory pre-implant variables, might provide significant predictive powers to explain post-implant speech perception skills.

4.4 Summary and Implications for Future Research

The findings from adults who used unilateral CIs or bimodal hearing in this study demonstrated that some individuals perform challenging listening tasks, such as talker and regional accent discrimination, very successfully. Other CI recipients though struggled to discriminate between talkers on either task. Access to low-frequency acoustic cues through a contralateral HA might have helped some participants perform these tasks (i.e., AAM, ABM and ABW) but for others who used bimodal hearing (e.g., AAD, ABB and ABO) access to the low-frequency acoustic cues did not help them perform either listening task. Acoustic analyses of stimuli used for the discrimination tasks suggested that listeners use F0 and speaking rate to assist with talker discrimination but no clear pattern was observed. Additionally, for the regional accent discrimination task, some talkers might have had consistent acoustic-phonetic features that made them easier to discriminate (e.g., SF4 and NF3) compared to other talker-pairs.

It is likely that a number of both auditory and non-auditory factors interact and are used by listeners for talker discrimination abilities. Evidence has suggested that both pre-implant non-auditory and auditory factors account for performance with a CI (Blamey et al., 2013; Heydebrand et al., 2007). In addition, research has demonstrated that when combined with pre-implant factors, verbal learning and memory skills can account for a significant amount of variability in post-implantation performance (Pisoni et al., in press). These findings, in conjunction with the outcomes of this study, suggest that more research with larger adult populations across all ages who use unilateral CIs, bilateral CIs, or bimodal hearing is required to fully understand and explain the variability in outcome performance.

Highlights.

Performance variability was observed across listeners for both discrimination tasks

Some adults benefitted from the addition of acoustic cues provided through a HA

Talker speaking rate and F0 helped with talker discrimination

Salient spectral cues were important for accent discrimination

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by the NIH/NIDCD (R03 DC008383 to the first author and T32 DC00012 to the third author) and by the Psi Iota XI Philanthropic Organization. We would like to thank sincerely two anonymous reviewers of previous versions of this paper. Their contributions significantly improved the presentation of our findings.

Abbreviations

- CI

Cochlear Implant

- HA

Hearing Aid

- PTA

Pre-Implant Pure-Tone Average

- PTS_CI

Post-Implant Pure-Tone Average

- SPEAK

Spectral Peak

- ACE

Advanced Combination Encoder

- CIS

Continuous Interleaved Sampling

- MPS

Multiple Pulsatile Sampler

- ANOVA

Analysis of Variance

APPENDIX

Appendix A

Sentences Spoken by Northern Talkers

NF1 – Only the most accomplished artists obtain popularity.

NF2 – One-upmanship is practiced by both sides in a total war.

NF3 – Would you please confirm government policy regarding waste removal.

NF4 – The surplus shoes were sold at a discount price.

NM1 – Poach the apples in this syrup for 12 minutes, drain them and cool.

NM2 – To use these new ways in daily life is the last step.

NM3 – Contrast trim provides other touches of color.

NM4 – Whether historically fact or not, the legend has a certain symbolic value.

Sentences Spoken by Southern Talkers

SF1 – The blue rug was suspiciously bright and new.

SF2 – Technical writers can abbreviate in bibliographies.

SF3 – They own a big house in the remote countryside.

SF4 – Toss a die until an ace appears.

SM1 – He was kneeling to tie his shoelaces.

SM2 – It will accommodate firing rates as low as half a gallon an hour.

SM3 – The two artists exchanged autographs.

SM4 – But this doesn’t detract from its merit as an interesting if not great film.

Footnotes

Conflict Of Interest:

None of the authors has a conflict of interest associated with their involvement in this project.

Financial Disclosures: Funding for this study was provided by the NIH/NIDCD (R03 DC008383 to the first author and T32 DC00012 to the third author) and by the Psi Iota XI Philanthropic Organization.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bierer JA, Spindler E, Bierer SM, Wright R. An examination of sources of variability across the Consonant-Nucleus-Consonant Test in cochlear implant listeners. Trends Hear. 2016;20:1–8. doi: 10.1177/2331216516646556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blamey P, Arndt P, Bergeron F, Bredberg G, Brimacombe J, Facer G, … Whitford L. Factors affecting auditory performance of postlinguistically deaf adults using cochlear implants. Audiology and Neuro-Otology. 1996;1:293–306. doi: 10.1159/000259212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blamey P, Artieres F, Baskent D, Bergeron F, Beynon A, Burke E, … Lazard DS. Factors affecting auditory performance of postlinguistically deaf adults using cochlear implants: an update with 2251 patients. Audiology and Neuro-Otology. 2013;18:36–47. doi: 10.1159/000343189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blamey PJ, Maat B, Baskent D, Mawman D, Burke E, Dillier N, … Lazard DS. A Retrospective Multicenter Study Comparing Speech Perception Outcomes for Bilateral Implantation and Bimodal Rehabilitation. Ear and Hearing. 2015;36:408–416. doi: 10.1097/aud.0000000000000150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CA, Bacon SP. Low-frequency speech cues and simulated electric-acoustic hearing. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2009;125:1658–1665. doi: 10.1121/1.3068441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ching TYC, van Wanrooy E, Dillon H. Binaural-bimodal fitting or bilateral implantation for managing severe to profound deafness: A review. Trends in Amplification. 2007;11:161–192. doi: 10.1177/1084713807304357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SJ, Lee JB, Bahng J, Lee WK, Park CH, Kim HJ, Lee JH. Effect of low frequency on speech performance with bimodal hearing in bilateral severe hearing loss. Laryngoscope. 2016;126(12):2817–2822. doi: 10.1002/lary.26014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clopper CG, Pisoni DB. Some acoustic cues for the perceptual categorization of American English regional dialects. Journal of Phonetics. 2004;32:111–140. doi: 10.1016/s0095-4470(03)00009-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clopper CG, Pisoni DB, de Jong K. Acoustic characteristics of the vowel systems of six regional varieties of American English. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2005;118:1661–1676. doi: 10.1121/1.2000774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firszt JB, Holden LK, Reeder RM, Cowdrey L, King S. Cochlear implantation in adults with asymmetric hearing loss. Ear and Hearing. 2012;33:521–533. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31824b9dfc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher WM, Doddington GR, Goudie-Marshall KM. The DARPA speech recognition research database: specifications and status. Proceedings of the DARPA Speech Recognition Workshop; 1986. pp. 93–99. [Google Scholar]

- Francis HW, Yeagle JD, Bowditch S, Niparko JK. Cochlear implant outcome is not influenced by the choice of ear. Ear and Hearing. 2005;26(Suppl):7S–16S. doi: 10.1097/00003446-200508001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu QJ, Chinchilla S, Nogaki G, Galvin JJ. Voice gender identification by cochlear implant users: The role of spectral and temporal resolution. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2005;118:1711–1718. doi: 10.1121/1.1985024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gantz BJ, Woodworth GG, Knutson JF, Abbas PJ, Tyler RS. Multivariate predictors of audiological success with multichannel cochlear implants. Annals of Otology Rhinology and Laryngology. 1993;102(12):909–916. doi: 10.1177/000348949310201201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford RH, Dorman MF, Shallop JK, Sydlowski SA. Evidence for the expansion of adult cochlear implant candidacy. Ear and Hearing. 2010;31:186–194. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e3181c6b831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomaa NA, Rubinstein JT, Lowder MW, Tyler RS, Gantz BJ. Residual speech perception and cochlear implant performance in postlingually deafened adults. Ear and Hearing. 2003;24:539–544. doi: 10.1097/01.AUD.0000100208.26628.2D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay-McCutcheon MJ, Peterson NR, Rosado CA, Pisoni DB. Identification of acoustically similar and dissimilar vowels in profoundly deaf adults who use hearing aids and/or cochlear implants: Some preliminary findings. American Journal of Audiology. 2014;23:57–70. doi: 10.1044/1059-0889(2013/13-0009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heydebrand G, Hale S, Potts L, Gotter B, Skinner M. Cognitive predictors of improvements in adults' spoken word recognition six months after cochlear implant activation. Audiology and Neuro-Otology. 2007;12:254–264. doi: 10.1159/000101473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden LK, Firszt JB, Reeder RM, Uchanski RM, Dwyer NY, Holden TA. Factors affecting outcomes in cochlear implant recipients implants with a perimodiolar electrode array located in the scala tympani. Otology & Neurotology. 2016;37:1662–1668. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000001241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illg A, Bojanowicz M, Lesinski-Schiedat A, Lenarz T, Buchner A. Evaluation of the bimodal benefit in a large cohort of cochlear implant subjects using a contralateral hearing aid. Otology & Neurotology. 2014;35:e240–244. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000000529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Incerti P, Ching TYC, Cowan R. A systematic review of electric-acoustic stimulation. Trends in Amplification. 2013;17:3–26. doi: 10.1177/1084713813480857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji C, Galvin JJ, 3rd, Xu A, Fu QJ. Effect of speaking rate on recognition of synthetic and natural speech by normal-hearing and cochlear implant listeners. Ear and Hearing. 2013;34:313–323. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31826fe79e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk KI, Houston DM, Pisoni DB, Sprunger AB, Kim-Lee Y. Talker discrimination and spoken word recognition by adults with cochlear implants. Paper presented at the Association for Research in Otolaryngology Twenty-Fifth Midwinter Meeting; St. Petersburg, FL. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kong YY, Cruz R, Jones JA, Zeng FG. Music perception with temporal cues in acoustic and electric hearing. Ear and Hearing. 2004;25:173–185. doi: 10.1097/01.aud.0000120365.97792.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong YY, Mullangi A, Marozeau J. Timbre and speech perception in bimodal and bilateral cochlear-implant listeners. Ear and Hearing. 2012;33:645–659. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e318252caae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong YY, Stickney GS, Zeng FG. Speech and melody recognition in binaurally combined acoustic and electric hearing. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2005;117:1351–1361. doi: 10.1121/1.1857526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krull V, Luo X, Iler Kirk K. Talker-identification training using simulations of binaurally combined electric and acoustic hearing: Generalization to speech and emotion recognition. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2012;131:3069–3078. doi: 10.1121/1.3688533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazard DS, Vincent C, Venail F, Van de Heyning P, Truy E, Sterkers O, … Blamey PJ. Pre-, per- and postoperative factors affecting performance of postlinguistically deaf adults using cochlear implants: a new conceptual model over time. PLoS One. 2012;7:e48739. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T, Fu QJ. Effects of spectral shifting on speech perception in noise. Hearing Research. 2010;270:81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Zhang G, Galvin JJ, Fu QJ. Mandarin speech perception in combined electric and acoustic stimulation. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone/0112471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Zhang G, Kang H-Y, Liu S, Han D, Fu QJ. Effects of speaking style on speech intelligibility for Mandarin-speaking cochlear implant users. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2011;129:EL242–EL247. doi: 10.1121/1.3582148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macmillan NA, Creelman CD. Detection theory: A user's guide. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Marx M, James C, Foxton J, Capber A, Fraysse B, Barone P, Deguine O. Speech prosody perception in cochlear implant users with and without residual hearing. Ear and Hearing. 2015;36:239–248. doi: 10.1097/aud.0000000000000105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moberly AC, Bates C, Harris MS, Pisoni DB. The enigma of poor performance by adults with cochlear implants. Otology & Neurotology. 2016;37:1522–1528. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000001211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moberly AC, Lowenstein JH, Nittrouer S. Word recognition variability with cochlear implants: "Perceptual attention" versus "auditory sensitivity". Ear and Hearing. 2016;37:14–26. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulhern L, Cullington H. Does acoustic fundamental frequency information enhance cochlear implant performance? Cochlear Implants International. 2014;15(2):101–108. doi: 10.1179/1754762813y.0000000057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie K, Barco A, Zeng FG. Spectral and temporal cues in cochlear implant speech perception. Ear and Hearing. 2006;27:208–217. doi: 10.1097/01.aud.0000202312.31837.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisoni DB, Broadstock A, Wucinich T, Safdar N, Miller K, Hernandez LR, … Moberly AC. Verbal learning and memory after cochlear implantation in postlingually deaf adults: Some new findings with the CVLT-II. Ear and Hearing. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000530. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss LA, Eggleston JL, Walker EP, Oh Y. Two ears are not always better than one: Mandatory vowel fusion across spectrally mismatched ears in hearing-impaired listeners. Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology. 2016;17:341–356. doi: 10.1007/s10162-016-0570-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schvartz KC, Chatterjee M, Gordon-Salant S. Recognition of spectrally degraded phonemes by younger, middle-aged, and older normal-hearing listeners. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2008;124:3972–3988. doi: 10.1121/1.2997434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stickney GS, Loizou PC, Mishra LN, Assmann PF, Shannon RV, Opie JM. Effects of electrode design and configuration on channel interactions. Hearing Research. 2006;211:33–45. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson BA, Dorman MF. Cochlear implants: A remarkable past and a brilliant future. Hearing Research. 2008;242:3–21. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L, Pfingst BE. Spectral and temporal cues for speech recognition: Implications for auditory prostheses. Hearing Research. 2008;242:132–140. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L, Thompson CS, Pfingst BE. Relative contributions of spectral and temporal cues for phoneme recognition. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2005;117:3255–3267. doi: 10.1121/1.1886405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon YS, Li Y, Fu QJ. Speech recognition and acoustic features in combined electric and acoustic stimulation. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2012;55:105–124. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2011/10-0325). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon YS, Shin YR, Gho JS, Fu QJ. Bimodal benefit depends on the performance difference between a cochlear implant and a hearing aid. Cochlear Implants International. 2015;16:159–167. doi: 10.1179/1754762814Y.0000000101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng FG. Trends in cochlear implants. Trends in Amplification. 2004;8(1):1–34. doi: 10.1177/108471380400800102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]