Abstract

Introduction

Sexually transmitted diseases continue to increase in the U.S. There is a growing need for financially viable models to ensure the longevity of safety-net sexually transmitted disease clinics, which provide testing and treatment to high-risk populations. This micro-costing analysis estimated the number of visits required to balance cost and revenue of a sexually transmitted disease clinic in a Medicaid expansion state.

Methods

In 2017, actual and projected cost and revenues were estimated from the Rhode Island sexually transmitted disease clinic in 2015. Projected revenues for a hypothetical clinic offering a standard set of sexually transmitted disease services were based on Medicaid, private (“commercial”) insurance, and institutional (“list price”) reimbursement rates. The number of visits needed to cover clinic costs at each rate was assessed.

Results

Total operating cost for 2,153 clinic visits was estimated at $255,769, or $119 per visit. Laboratory testing and salaries each accounted for 44% of operating costs, medications for treatment 7%, and supplies 5%; 28% of visits used insurance. For a standard clinic offering a basic set of sexually transmitted disease services to break even, a projected 73% of visits need to be covered at the Medicaid rate, 38% at private rate, or 11% at institutional rate.

Conclusions

Sexually transmitted disease clinics may be financially viable when a majority of visits are billed at a Medicaid rate; however, mixed private/public models may be needed if not all visits are billed. In this manner, sexually transmitted disease clinics can be solvent even if not all visits are billed to insurance, thus ensuring access to uninsured or underinsured patients.

INTRODUCTION

Sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), including syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia continue to be a major cause of morbidity in the U.S., at an estimated $15.6 million in annual direct medical costs.1 In 2015, STD rates reached an all-time high in reported cases.2 Safety-net STD clinics have historically provided accessible and affordable services to uninsured or underinsured patients.3 Initially, STD clinics operated on state and federal funds with no fee to patients; however, since 2003, funding for STD programming has been cut by nearly 40%,4 which has reduced capacity across the U.S.5 Even when the cost of STD testing and treatment is high, governments have recognized the value of treating STDs as a public good that prevents the further spread of disease.6 Given the decrease in funding amidst increasing STD rates,2 STD programs have sought to diversify their revenue streams through third-party billing to insurance. This is partly because of the increase in insurance coverage nationwide7 after passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act in 2010,8 which included: free access to preventive care; a requirement for insurance plans to cover gonorrhea and chlamydia testing without copays for women; syphilis testing, HIV testing, and STD counseling without copays for all high risk adults9,10; and the accompanying Medicaid expansion in many states beginning in 2014. Yet, the ability of STD clinics to be viable while implementing billing practices is largely unknown.

Safety-net STD services continue to be needed across the U.S., even in areas with high insurance coverage.11–14 Patients with health insurance may continue to use safety-net services because of non-monetary considerations, such as the desire to keep STD testing history private from primary care providers, insurers, or family members who share an insurance plan.12,13,15 STD clinics may also be perceived as providing higher quality STD care services12 or as being more inclusive of gender and sexual minority patients compared with general practices.12 Financial barriers to seeking STD services from traditional medical establishments may also persist among the insured through cost sharing via copays or deductibles.15 These clinics provide rapid treatment, as a patient may wait days or weeks for a primary care appointment. Additionally, safety-net STD clinics continue to provide services to remaining uninsured populations. Given this demonstrated need for low-cost, accessible STD services, as well as the increasing STD rates across the U.S., maintaining the financial solvency of these services after implementation of the Affordable Care Act should be a public health priority.

Evaluating the costs of delivering safety-net STD services is an important step in developing cost-effective models of care. Micro-costing studies in health care identify and measure all costs and sources of income associated with delivery of a given healthcare service,16 and have been previously conducted in STD care settings with the goal of determining cost effectiveness and informing policy.17–22 Most have focused on HIV only.17–22 No previous studies in the U.S. have assessed overall operational costs of an STD clinic.

The purpose of the present study is to evaluate the financial viability of a publicly funded, hospital-based STD clinic in Rhode Island. Rhode Island experienced a substantial increase in insurance coverage after implementation of the Affordable Care Act and Medicaid expansion,7 which has presented the possibility of billing for STD services that were being provided at no charge to patients.

METHODS

Study Population

The analysis was conducted in 2017. A micro-costing approach16 was used to calculate cost and revenue at a publicly funded STD clinic based on all visits from January to December 2015. The clinic offered testing for HIV, hepatitis C virus, gonorrhea and chlamydia at three sites (pharyngeal, rectal, urogenital), syphilis, and trichomonas. All patients were asked to use insurance, if they had it, to cover laboratory testing only. Insured patients were not required to provide insurance information to receive testing.

Measures

The analysis first calculated actual clinic costs and revenue. The actual total operating cost was the sum of staff salaries as a fixed cost. Salaries represent the midpoint salary ranges plus fringe at one institution, and were based on operating hours of the STD clinic plus one additional staff hour for set up and closing. Costs of laboratory testing, laboratory specimen collection supplies, and treatment were directly assessed from the clinic’s administrative records. These data were used to calculate annual marginal clinic costs based on the following patient flow: visit with a trained test counselor; specimen collection and testing for gonorrhea and chlamydia (urine, oral, or rectal nucleic acid amplification tests [NAAT]), syphilis rapid plasma reagin (RPR), and HIV; phlebotomy services for blood sample collection; visit with registered nurse in case of symptoms; visit with a medical provider upon nurse recommendation (i.e., physician assistant); and treatment, either same day or upon receipt of positive test result.

Using the cost amounts from the actual clinic, break-even amounts needed to recoup costs for a basic set of STD services were projected at Medicaid, private (“commercial”) insurance, and institutional (“list price”) reimbursement rates. The projected total operating cost was calculated under the assumption that each visit included four tests: one blood test for HIV, one RPR blood test for syphilis, and one urine NAAT each for gonorrhea and chlamydia. Extragenital testing was not included in the projected costs because the rate of this may vary by the risk behaviors of a given clinic population. Testing for hepatitis C virus or trichomonas were not included because they are not recommended as general screening tests, and occur at a much lower frequency and volume (fewer than 5%–10% of the clinic) than other tests. Therefore, standard STD testing included HIV, syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia testing. The total number of tests and the percentage of tests that were positive thus requiring treatment were based on the percentages from the actual clinic data. Costs of treatment were calculated assuming that all visits with a positive syphilis test were treated with one intramuscular penicillin G benzathine (Bicillin L-A®) injection, patients with a positive chlamydia test were treated once orally with 1 gram azithromycin, and patients with a positive gonorrhea test were treated with ceftriaxone 250 mg intramuscularly once and once orally with 1 gram azithromycin.23 Treatment costs for HIV were not included because a positive HIV test result would be referred for care and treatment outside of the clinic. Overhead costs (i.e., rent and utilities) were not included, assuming that services would be implemented as part of an existing clinic structure.

Actual income generated by the clinic was based on the total number of tests billed to insurance plus costs for treatment of one STD, and was based on reimbursement from Medicaid at the 2015 fee schedule. Estimates for projected income were based on Medicaid, private insurers, and the institutional list price reimbursement rates in 2015 for lab tests only, lab tests and provider time, or lab tests and provider time and treatment. Data on actual provider billing and private insurance actual reimbursement were unavailable and were estimated. All provider time was billed as a Level 3 new patient office visit, which is a 30-minute initial consultation (Current Procedural Terminology code 99203). Reimbursement amounts for private insurers were estimated at 152% of Medicaid prices, based on the midpoint from several sources suggesting ranges from 47% to 56% greater than Medicaid.24–26 Institutional list prices were based on the out-of-pocket charges a patient would be expected to pay in 2015 if they had no insurance, and were generally higher than the private insurance reimbursement rates. The number of visits needed to break even was determined by where the marginal cost and revenues were equal.

To estimate revenue from treatment, the rate of positive tests was assigned proportionally, based on actual clinic data. For example, based on the number of positive tests across the total visits in the clinic, 3%, 6% and 11% of visits are expected to have a positive syphilis, gonorrhea, or chlamydia test, respectively, and all positive tests were assumed to be treated. For the projection, the number of visits was multiplied by 3%, 6%, and 11%, and that was multiplied by the reimbursement rate for each treatment. Assuming that patients testing positive would be treated onsite, no additional provider time was charged for those requiring treatment.

RESULTS

In 2015, there were 2,153 visits to the Rhode Island STD Clinic. The clinic’s total estimated operating cost was $255,769 (Table 1). Salaries accounted for 44% of the operating costs, laboratory testing 44%, supplies 5%, and treatment medications 7%. The cost per visit was $119. Appendix Table 1 presents itemized costs for salary, supply, testing, and treatment expenses for those visits. Twenty-eight percent of visits (n=595) used insurance to cover the cost of services at their clinic visit, resulting in an estimated $83,576 in income generated from laboratory tests only (per this clinic’s practice), assuming all visits were reimbursed at Medicaid rates (Table 2). Appendix Table 2 shows the estimated actual income based on actual clinics costs and rate of insurance usage. Appendix Table 3 shows the insurance reimbursement rates for the Current Procedural Terminology codes used to estimate projected income based on Medicaid, private, and institutional list prices.

Table 1.

Summary of Costs by Category Based on Clinic Visits in 2015a

| Operating cost categories | Cost | Percent of total |

|---|---|---|

| Total salary costb | $111,697 | 44 |

| Total lab testing cost | $112,253 | 44 |

| Total supplies cost | $13,167 | 5 |

| Total treatment cost | $18,651 | 7 |

| Total operating cost | $255,769 | 100 |

| Cost per hour | $429 | |

| Cost per visit | $119 |

Based on the total number of hours the STD clinic was open, plus an additional hour for clinical tasks to set up and close down the clinic.

Unit costs are listed in Appendix Table 1.

STD, sexually transmitted diseases

Appendix Table 1.

Operational Costs of the Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STD) Clinica

| Category | Unit cost | # of units | Category total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Salaries (per hour)b | |||

| Physician assistant | $46.90 | ||

| Nurse | $38.37 | ||

| Office manager | $26.41 | ||

| Medical assistant | $19.50 | ||

| Secretary | $19.11 | ||

| Fringe (24.7%) | $37.12 | ||

| ($187.41) | 596 hours | $111,697 | |

| Supplies (per single item) | |||

| Gonorrhea/Chlamydia kit | $2.50 | ||

| Urine cups | $0.37 | ||

| Plastic bags for specimens | $0.06 | ||

| Gauze 2×2 | $0.04 | ||

| Alcohol wipes | $0.01 | ||

| Band-Aids | $0.04 | ||

| Gloves | $0.04 | ||

| Blood collection tubes | $0.80 | ||

| Tourniquets | $1.12 | ||

| Butterfly needles | $1.13 | ||

| ($6.12) | 2,153 visits | $13,176 | |

| Laboratory Tests (per test) | |||

| Chlamydia (NAAT) | $13.68 | 3,992 tests | |

| Gonorrhea (NAAT) | $13.68 | 3,994 tests | |

| HIV | $1.21 | 1,885 tests | |

| Syphilis (RPR) | $0.37 | 1,957 tests | |

| $112,253 | |||

| Medications (treatment, contract price per dose) | |||

| Penicillin G benzathine (Bicillin L-A®) 2.4M units (IM) | $209.95 | 73 syphilis treatments | |

| Ceftriaxone 250mg (IM) | $0.71 | 125 gonorrhea treatments | |

| Azithromycin (1 gram) | $9.09 | 356 gonorrhea and chlamydia treatments | |

| $18,651 |

Analysis does not include overhead costs. The analysis evaluates the cost of operating an STD clinic assuming facility costs (e.g., rent, utilities) are covered as part of the larger clinical institution.

Salaries represent the midpoint salary ranges at one institution.

NAAT, nucleic acid amplification test; RPR, rapid plasma reagin test; IM, intramuscular dose

Table 2.

Number of Visits and Tests Performed at the Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STD) Clinic in 2015

| Clinic Characteristic | N |

|---|---|

| Total number of days opena | 149 |

| Total number of hours opena | 596 |

| Total number of visits | 2,153 |

| Total number of visits where insurance was used | 595 |

| Total number of tests performed (number billed to insurance) | |

| HIV | 1,885 (534) |

| RPR | 1,957 (568) |

| Gonorrhea (Urine) | 2,049 (582) |

| Chlamydia (Urine) | 2,048 (582) |

| Gonorrhea (Oral) | 1,238 (389) |

| Chlamydia (Oral) | 1,238 (389) |

| Gonorrhea (Rectal) | 707 (235) |

| Chlamydia (Rectal) | 706 (234) |

| Total number of positive testsb | |

| Syphilis | 73 |

| Gonorrhea (at least one site) | 125 |

| Chlamydia (at least one site) | 231 |

| Total income generated from testing onlyc | $83,576 |

| Total income generated from testing and treatmentc | $86,271 |

| Total income generated from testing, treatment, and provider timec | $103,526 |

Based on operating hours of the STD Clinic (Wednesday, Thursday, Friday from 12:30PM-3:30PM), holidays excluded, plus an additional hour for administrative tasks.

For the purposes of this analysis, it was assumed all people with a positive syphilis test were treated with one intramuscular penicillin G benzathine (Bicillin L-A®) injection, individuals with a positive chlamydia test were treated with azithromycin 1 gram orally once, and individuals with a positive gonorrhea test were treated with ceftriaxone 250mg intramuscularly once and azithromycin 1 gram orally once.

Based on visits where insurance was used to bill (Appendix Table 2 provides Medicaid income estimates). Actual clinic only billed for laboratory testing but not for treatment and provider time. Reimbursement rates were based on the Medicaid fee schedule, a low estimate.

RPR, rapid plasma reagin test

Appendix Table 2.

Estimated Income Based on Actual Clinic Costs and Insurance Use

| Total number of tests where insurance was used | N | Income (Medicaid) | Income (Private) | Income (List) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV | 534 | $10,610.58 | $16,128.08 | $28,836.00 |

| Syphilis (RPR) | 568 | $2,033.44 | $3,090.83 | $17,040.00 |

| Gonorrhea (Urine) | 582 | $17,122.44 | $26,026.11 | $63,438.00 |

| Chlamydia (Urine) | 582 | $17,122.44 | $26,026.11 | $63,438.00 |

| Gonorrhea (Oral) | 389 | $11,444.38 | $17,395.46 | $42,401.00 |

| Chlamydia (Oral) | 389 | $11,444.38 | $17,395.46 | $42,401.00 |

| Gonorrhea (Rectal) | 235 | $6,913.70 | $10,508.82 | $25,615.00 |

| Chlamydia (Rectal) | 234 | $6,884.28 | $10,464.11 | $25,506.00 |

| Total income for positive tests (Treatment) | Income from treatment | |||

| Syphilis | 73 | $919.07 | $1,396.99 | $4,891.00 |

| Gonorrhea (At least one site, individual patients) | 125 | $1,645.00 | $2,608.75 | $11,125.00 |

| Chlamydia (At least one site, individual patients) | 231 | $131.67 | $200.14 | $5,082.00 |

| Income from provider time | ||||

| Income generated from provider billing | 595 | $17,255.00 | $26,227.60 | $123,165.00 |

| Total income based on actual clinic data | $103,526.38 | $157,468.45 | $452,938.00 | |

RPR, rapid plasma reagin test

Appendix Table 3.

Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) Codes for Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STD) Testing

| CPT code | Description | Medicaida | Privateb | Listc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical provider time | ||||

| 99201 | New patient office visit, Level 1 | $16.72 | $25.41 | $83.00 |

| 99202 | New patient office visit, Level 2 | $27.24 | $41.40 | $135.00 |

| 99203 | New patient office visit, Level 3 | $29.00 | $44.08 | $207.00 |

| 99204 | New patient office visit, Level 4 | $45.00 | $68.40 | $350.00 |

| 99205 | New patient office visit, Level 5 | $46.00 | $69.92 | $449.00 |

| Procedural | ||||

| 96372 | IM Injection for penicillin G benzathine (Bicillin L-A ®) and Ceftriaxone | $12.59 | $19.14 | $67.00 |

| 36415 | Routine Venipuncture | $1.80 | $2.74 | $17.00 |

| Laboratory | ||||

| 87491 | Chlamydia (NAAT) | $29.42 | $44.72 | $109.00 |

| 87591 | Gonorrhea (NAAT) | $29.42 | $44.72 | $109.00 |

| 87389 | HIV | $19.87 | $30.20 | $54.00 |

| 86592 | Syphilis (RPR) | $3.58 | $5.44 | $30.00 |

Notes: All provider time was billed as a Level 3 new patient office visit; costs for Levels 1, 2, 4, and 5 are included here for informational purposes only.

Based on 2015 Medicaid fee schedule.

Based on 152% of 2015 Medicaid fee schedule cost.

Based on current list prices at one institution.

IM, intramuscular dose; NAAT, nucleic acid amplification test; RPR, rapid plasma reagin test

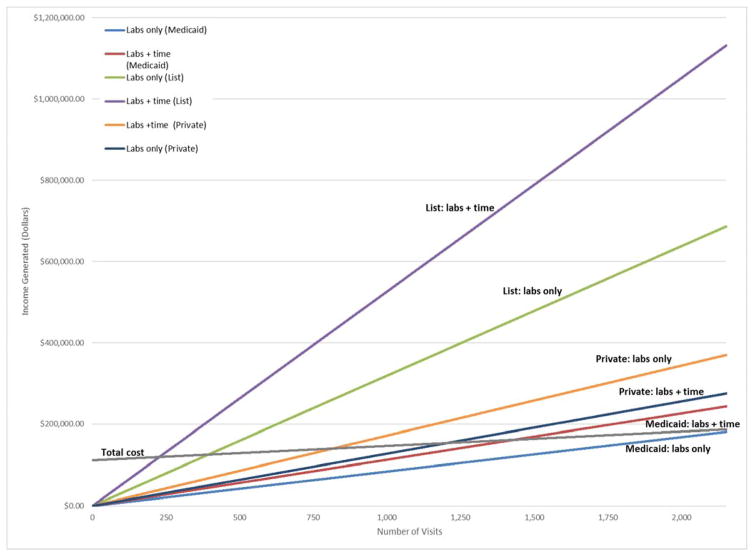

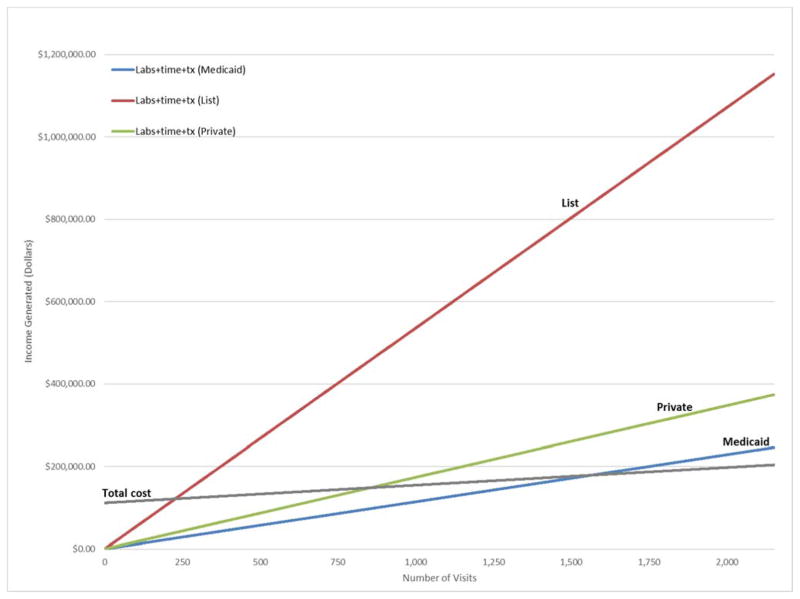

Based on cost projections for a clinic offering a standard set of STD services, the maximum costs for 2,153 visits would be $187,145 excluding treatment costs (Figure 1), or $204,117 including treatment costs (Figure 2). When reimbursing for labs only, a clinic would break even: at no point at Medicaid, and at 56% (n=1,205) of visits at private, or 18% (n=394) of visits at institutional list rates (Figure 1). To break even when reimbursing for labs and provider time, a clinic would have to bill 67% of visits (n=1,432) at Medicaid, or 38% (n=817) of visits at private, or 11% (n=228) of visits at institutional list price (Figure 1). To break even when reimbursing for labs, provider time, and treatment (Figure 2), a clinic would have to bill 73% of visits (n=1,565) at Medicaid, or 38% (n=817) of visits at private, or 11% (n=227) of visits at institutional list price.

Figure 1.

Potential income for an in-house STD clinic by number of visits billed.

Notes: Potential income for an in-house STD clinic offering a standard set of services, based on number of visits billed for laboratory tests alone or in addition to provider time (but no treatment), using list, private, or Medicaid (2015) reimbursement rates compared with projected clinic operating cost.

Sources: Author’s analysis of costs from Lifespan clinic, 2015; Medicaid Fee Schedule, 2015

STD, sexually transmitted diseases

Figure 2.

Potential income for in-house STD clinic based on number of visits billed, including treatment costs.

Notes: Potential income for in-house STD clinic offering a standard set of services, based on number of visits billed for laboratory tests alone, provider time, and treatment using list, private, or Medicaid (2015) reimbursement rates as compared with total projected clinic costs, including costs for treatment.

Sources: Author’s analysis of costs from Lifespan clinic, 2015; Medicaid Fee Schedule for 2015

STD, sexually transmitted diseases; tx, treatment

DISCUSSION

This is among the first studies to perform a detailed cost analysis at a publicly funded STD clinic in a Medicaid expansion state and to project break-even amounts for offering a basic set of STD services.17–22 Given that only a portion of visits will be billed to insurance, results suggest that a clinic might not be financially viable if only billed to Medicaid, but could be financially viable when other types of insurance reimbursements are available. Broadly speaking, the results suggest that an STD clinic can be viable, even when not all visits are billed to an insurer, and provide services even to those who are uninsured without facing a deficit. For STD clinics in which most visits can be billed to some type of insurance, the clinic may be financially viable or even generate revenue; however, those serving patients with a high proportion of visits that cannot be billed to insurance may need to consider other forms of revenue generation, mixed public/private reimbursement models, cost containment strategies, or benefit from additional state and federal funding.

In this analysis, projected revenues were based on a fee-for-service model in which all visits are reimbursed by one type of insurance. In reality, public insurers, private insurers, and even individuals could pay to cover the cost of visits. Forecasting the potential mix may be difficult, given that patients have options to use or not use insurance, and their desire to use or not use insurance may change based on type of insurance, amount of copays and deductibles, or non-financial reasons.12,13,15 Further complicating estimates is that private insurance and institutional list reimbursement rates are not publicly available, are not standardized across patients or hospitals, and are often negotiated on a per insurer or health system basis. By using 2015 Medicaid rates, which represent the minimum cost that would be reimbursed, this analysis provides a conservative baseline estimate of the number of visits that would need to be covered based on rates that are standardized and known. This approach could be used as a baseline for other STD clinics, to assess a financially viable service model based on the most conservative reimbursement structure.

The ability to achieve a viable model is based on the assumption that patients who report having insurance will use it to bill services. Yet, a previous analysis over 6 months at the same Rhode Island STD Clinic found that 30% of the total sample used insurance.27 This is in line with the current analysis at the same clinic over a full year, which found that 28% of visits used insurance, which is well below the 73% that would be needed to break even if all visits were based on Medicaid. The previous study also showed that 22% of the total sample used private or other insurance27 which is below the 38% of visits needed to break even at the private insurance rates, but exceeds the 11% of visits needed to break even at the list insurance rates. This makes the authors optimistic that a sufficient volume of visits would be reimbursed at an insurance rate that is higher than Medicaid and that would allow a clinic to be financially solvent.

Encouraging patients to use insurance to cover visits may be challenging and present an ethical dilemma. In a previous study, fewer than half of patients were willing to use insurance.27 Nearly two thirds of patients cite privacy as the biggest barrier to using insurance for services15,27 and the risk of exposure of receipt of STD services on an insurance bill28 or explanation of benefits may be a deterrent to seeking care, especially for youth covered by a parent’s plan or partner covered by a spouse’s plan. One of the primary reasons patients cite for obtaining testing at an STD clinic rather than a primary care clinic is because of preferences for anonymity and the option to not have their testing disclosed to a provider or on an electronic medical record.11,29 On one hand, encouraging at least some patients to use insurance to cover visits can help ensure that both insured and uninsured patients are served broadly. On the other hand, encouraging patients to use insurance may raise ethical questions of increasing patients’ risk of harm because of potential privacy losses and subsequent stigma that might ultimately push them away from care.

Even when services are billed to insurance, patients may have a choice of which insurance to bill, and previous research suggests a greater willingness to use Medicaid than private insurance for STD care.15 This study’s data suggest that STD clinics that rely mostly on Medicaid reimbursement to generate revenue will need to have a greater volume of patient visits, which may put greatest strain on staffing and resources, compared with clinics that can reimburse through private or institutional rates. However, Medicaid reimbursement is a superior option to providing free care to those who are uninsured in terms of clinic financing, but should be recommended with caution given the patient privacy tradeoffs. Rhode Island and other states that expanded Medicaid, may leverage improved coverage rates to provide STD services. Ideally, clinics would strive to have a mix of revenue generation through Medicaid and private insurance rates to balance the ability to sustainably provide services while protecting patients from undue cost burden or risk of privacy loss. But in recent years, a rollback of Medicaid expansion has been threatened, which could put funds for STD treatment programming in jeopardy. The shifting insurance landscape has led to debate regarding the continued need for state-funded safety-net STD clinics, because these might otherwise be covered by Medicaid expansion and private insurance. The analysis further suggests that, especially against a backdrop of escalating STD rates, continued state and federal funding is critical to the ability of these clinics to provide care to the uninsured and underinsured. As a central way to curb the spread of disease, STD testing remains an important public good that should be accessible to insured, uninsured, and underinsured alike, in service of public health of the broader population.

Limitations

Information on which specific visits used which types of insurance was not available, so estimates are based on the assumption that all visits were reimbursed by one type of insurance. Revenue estimates are conservative because they do not include: other potential resources that a clinic might use to offset costs (e.g., low cost medications through the 340B Drug Discount Program,30 discounts from insurance companies), revenue from non–fee-for-service billing approaches, HIV treatment or testing for other STDs, or reimbursement for follow-up provider visits. An estimated 58%–89% of private insurers benchmark to Medicaid rates,31 creating variability in the extent to which this analysis’ estimates accurately represent the practice of some private insurers; however, a majority of insurers will still benchmark to Medicaid. List prices are specific to one clinic at one institution, and vary widely across institutions. Thus, they may not be generalizable to other institutions. Limitations aside, this analysis is a template that other institutions may use to gauge the viability of their own clinic.

CONCLUSIONS

STD clinics continue to serve an important function by providing accessible and affordable STD testing and care. This analysis adds value by establishing a platform to assess the costs of STD clinics in a changing insurance landscape at a time when STD rates are increasing, and reinforces to policymakers the need for continued funding of these clinics through Medicaid expansion and other sources. Results suggest that an STD clinic can be financially viable and solvent while serving a broad population, of which half or fewer would need to be billed to insurance. Putting this into practice could suggest a shift toward a clinic culture where billing is the norm, but not billing is still accessible as a way to retain people in care who may fear risk of loss of privacy. Finally, although financial viability is an important part of providing care, STD services should be universally available, regardless of revenue generated, as an important service for the good of the public’s health in the U.S.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Dean is supported by the National Cancer Institute grants K01CA184288 and (Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center) P30CA006973; and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease grant (Johns Hopkins University Center for AIDS Research) P30AI094189. Drs. Dean, Raifman, and Nunn are supported by the National Institute of Mental Health grant R25MH083620. Dr. Chan is supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse grant R34DA042648, and National Institutes of Mental Health grants R34MH110369, R34MH109371, R21MH113431, and R21MH109360.

Footnotes

All authors contributed to the conception, analysis, and writing of the manuscript.

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

References

- 1.Owusu-Edusei K, Jr, Chesson HW, Gift TL, et al. The estimated direct medical cost of selected sexually transmitted infections in the United States, 2008. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40(3):197–201. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318285c6d2. https://doi.org/10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318285c6d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.CDC. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2015. Atlanta, GA: DHHS; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Celum CL, Bolan G, Krone M, et al. Patients attending STD clinics in an evolving health care environment. Demographics, insurance coverage, preferences for STD services, and STD morbidity. Sex Transm Dis. 1997;24(10):599–605. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199711000-00009. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007435-199711000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pang SA. Despite STDs Surging to 20-Year High, Congress Cuts FY ‘17 STD Funding. STD Cuts in Final FY17 Funding: National Coalition of STD Directors. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Association of State and Territorial Apprenticeship Directors, National Coalition of STD Directors. 2010 State General Revenue Cuts in HIV/AIDS, STD and Viral Hepatitis Programs. A Special Report of The National Alliance of State and Territorial AIDS Directors and The National Coalition of STD Directors. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Over M. The public interest in a private disease: an economic perspective on the government role in STD and HIV control. In: Holmes KK, Sparling PF, Mardh PA, editors. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 3. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 1999. pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen R, Martinez M, Zamitti E. Health insurance coverage: early release of estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, 2015. Division of Health Interview Statistics, National Center for Health Statistics; [Accessed November 29, 2017]. Published 2016. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/insur201605.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, 42 U.S.C. § 18001 (2010).

- 9. [Accessed August 21, 2017];Preventive care benefits for adults. www.healthcare.gov/preventive-care-adults/

- 10.Kaiser Family Foundation. [Accessed August 21, 2017];Preventive Services Covered by Private Health Plans under the Affordable Care Act. 2015 www.kff.org/health-reform/fact-sheet/preventive-services-covered-by-private-health-plans/

- 11.Cramer R, Leichliter JS, Gift TL. Are safety net sexually transmitted disease clinical and preventive services still needed in a changing health care system? Sex Transm Dis. 2014;41(10):628–630. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000187. https://doi.org/10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoover KW, Parsell BW, Leichliter JS, et al. Continuing need for sexually transmitted disease clinics after the Affordable Care Act. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(suppl 5):S690–695. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302839. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Washburn K, Goodwin C, Pathela P, Blank S. Insurance and billing concerns among patients seeking free and confidential sexually transmitted disease care: New York City sexually transmitted disease clinics 2012. Sex Transm Dis. 2014;41(7):463–466. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000137. https://doi.org/10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mehtani NJ, Schumacher CM, Johnsen LE, et al. Continued importance of sexually transmitted disease clinics in the era of the Affordable Care Act. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51(3):364–367. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.04.016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2016.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pearson WS, Cramer R, Tao G, Leichliter JS, Gift TL, Hoover KW. Willingness to use health insurance at a sexually transmitted disease clinic: a survey of patients at 21 U.S. clinics. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(8):1511–1513. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303263. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frick KD. Micro-costing quantity data collection methods. Med Care. 2009;47(7 suppl 1):S76. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819bc064. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819bc064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eggman AA, Feaster DJ, Leff JA, et al. The cost of implementing rapid HIV testing in sexually transmitted disease clinics in the United States. Sex Transm Dis. 2014;41(9):545–550. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000168. https://doi.org/10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schnippel K, Lince-Deroche N, van den Handel T, Molefi S, Bruce S, Firnhaber C. Cost evaluation of reproductive and primary health care mobile service delivery for women in two rural districts in South Africa. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0119236. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119236. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0119236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dandona L, Sisodia P, Prasad TL, et al. Cost and efficiency of public sector sexually transmitted infection clinics in Andhra Pradesh, India. BMC Health Serv Res. 2005;5:69. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-5-69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-5-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoenigl M, Graff-Zivin J, Little SJ. Costs per diagnosis of acute HIV infection in community-based screening strategies: a comparative analysis of four screening algorithms. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(4):501–511. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ912. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/civ912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shelley KD, Ansbro EM, Ncube AT, et al. Scaling down to scale up: a health economic analysis of integrating point-of-care syphilis testing into antenatal care in Zambia during pilot and national rollout implementation. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0125675. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125675. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0125675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kimaro GD, Mfinanga S, Simms V, et al. The costs of providing antiretroviral therapy services to HIV-infected individuals presenting with advanced HIV disease at public health centres in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: Findings from a randomised trial evaluating different health care strategies. PloS One. 2017;12(2):e0171917. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171917. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0171917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.CDC. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;66(5):526–528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.07.526. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krause T, Ukhanova M, Revere F. Private carriers’ physician payment rates compared with Medicare and Medicaid. Tex Med. 2016;112(6):e1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Senger A. Obamacare’s Impact on Doctors—An Update. The Heritage Foundation; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herrick D. Exchanging Medicaid for Private Insurance. National Center for Policy Analysis; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Montgomery MC, Raifman J, Nunn AS, et al. Insurance coverage and utilization at a sexually transmitted disease clinic in a Medicaid expansion state. Sex Transm Dis. 2017;44(5):313–317. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000585. https://doi.org/10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Emanuel D. Aetna envelopes reveal customers’ HIV status. CNN. 2017 Aug 25; [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mettenbrink C, Al-Tayyib A, Eggert J, Thrun M. Assessing the changing landscape of sexual health clinical service after the implementation of the Affordable Care Act. Sex Transm Dis. 2015;42(12):725–730. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000375. https://doi.org/10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.U.S. DHHS Health Resources and Services Administration. Section 340B Public Health Service Act. Pub. L. 102-585. www.hrsa.gov/opa/programrequirements/phsactsection340b.pdf.

- 31.Clemens J, Gottlieb JD, Molnár TL. The anatomy of physician payments: Contracting subject to complexity. NBER Work Pap Ser. 2015:21642. https://doi.org/10.3386/w21642.