Abstract

Antibiotic cement-coated intramedullary nails maintain a locally high antibiotic concentration while contributing to bone stability. We present a case of femoral subtrochanteric fracture in a patient with an infected nonunion who was successfully treated for an infection and nonunion using an antibiotic cement-coated tibial intramedullary nail. A 79-year-old woman with a right femoral subtrochanteric fracture underwent internal fixation using proximal femoral nail antirotation (PFNA). She developed osteomyelitis with nonunion at the surgical site 10 months postoperatively. We decided to insert an antibiotic cement-coated tibial intramedullary nail. After coating the nail with bone cement mixed with antibiotics, bone fixation was achieved by inserting the nail at the site of the PFNA. The patient's symptoms improved, symptoms from the infection disappeared, and bone union was confirmed. Osteomyelitis occurred because of postoperative infection following a proximal femoral fracture. Antibiotic cement-coated tibial intramedullary nails are an effective option to treat patients with osteomyelitis of the femur and achieve bone union where nonunion persists with shallow a intramedullary femoral canal.

Keywords: Osteomyelitis, Intramedullary fracture fixation, Surgical wound infection

INTRODUCTION

Treating patients with fractures and infected nonunions is a challenge for many orthopedic surgeons. In the past, infections were controlled solely after achieving union. Methods for infection control broadly include marginal resection, antibiotic-loaded cement insertion, and intravenous antibiotic use1,2,3). Bone union is achieved through external or internal fixation4). Antibiotic cement-coated intramedullary nails maintain a locally high antibiotic concentration while maintaining bone stability. There have been reports about using K-wires with antibiotic-impregnated cements for femurs with narrow diameter5). Yet, it is uncertain whether this method can maintain stability when bearing weight, especially in patients with femur fractures and subtrochanteric area. We present a case of femoral subtrochanteric fracture in a patient with an infected nonunion, where the infection and nonunion were successfully treated using an antibiotic cement-coated tibial intramedullary nail.

This article was approved by The Catholic University of Korea Catholic Medical Center (No. HC17ZCSI0026).

CASE REPORT

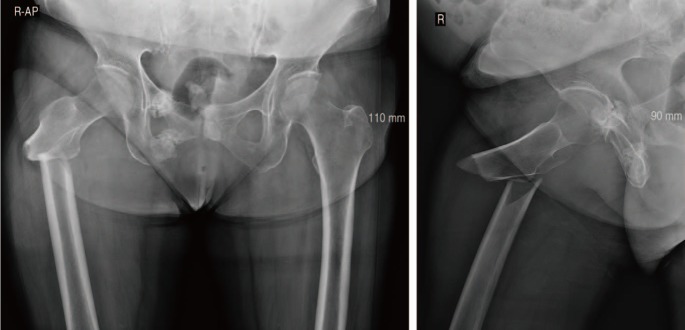

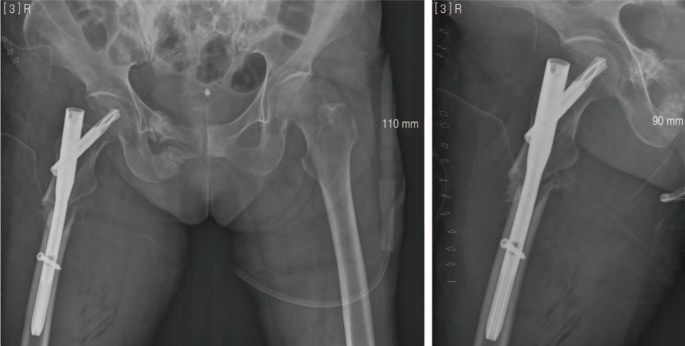

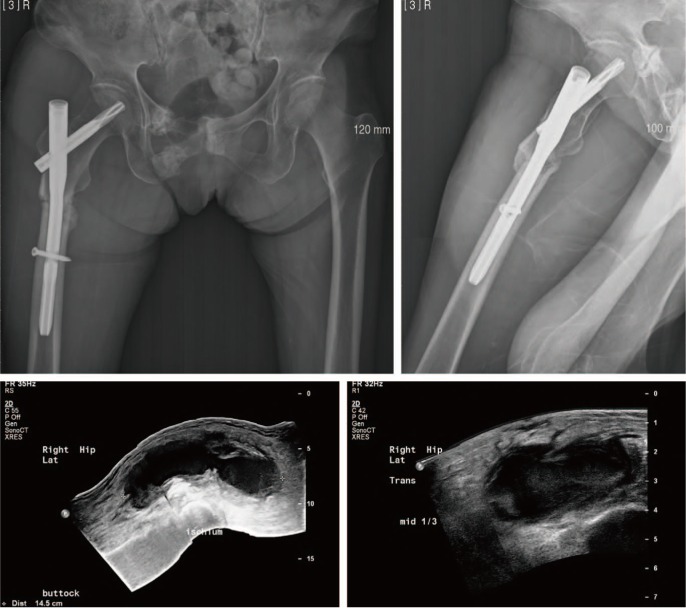

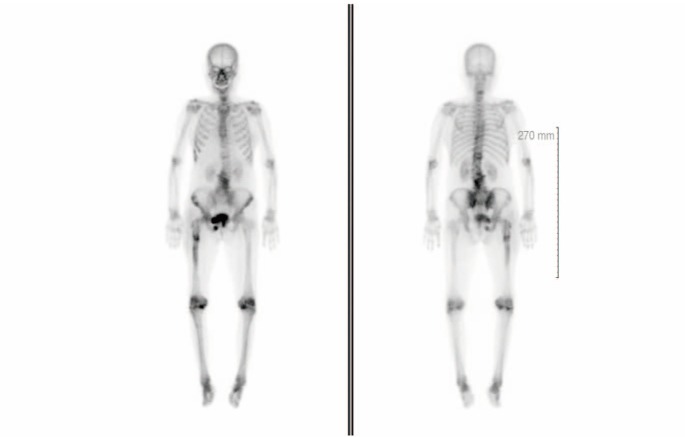

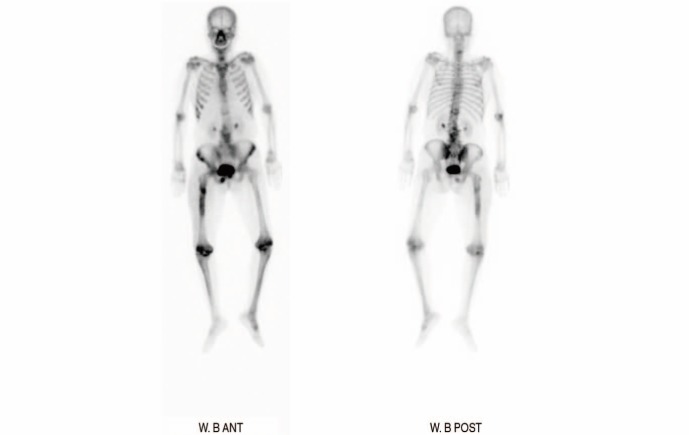

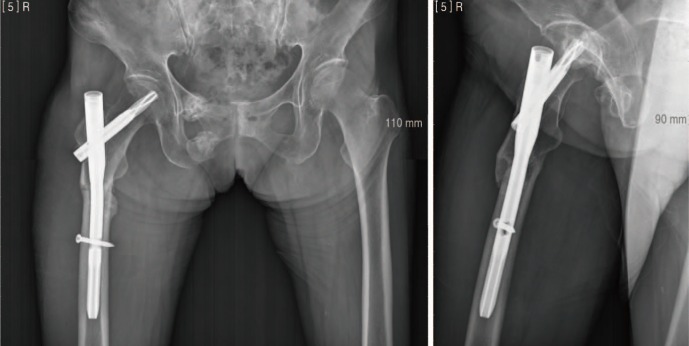

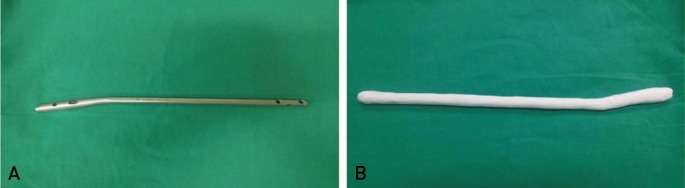

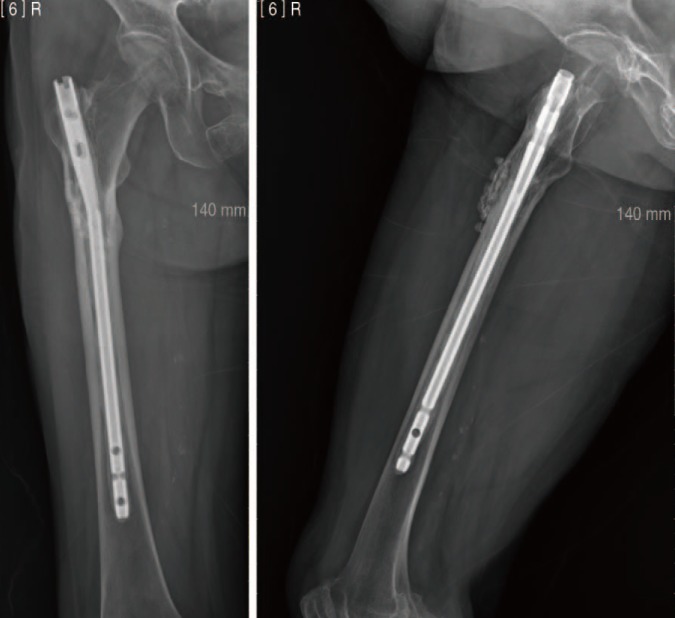

A 79-year-old women with hypertension and osteoporosis presented to the emergency department with right hip pain after slipping and falling on a rainy day. She was taking risedronate for 7 years to treat osteoporosis without a drug holiday. Radiography showed a right atypical femoral subtrochanteric fracture (Fig. 1), and internal fixation was performed using proximal femoral nail antirotation (PFNA). Autologous iliac crest bone graft was performed simultaneously, because of a high rate of atypical subtrochanteric fracture nonunion (Fig. 2). The patient's symptoms improved, and she was discharged from the hospital. Approximately 8 months postoperatively, while still undergoing outpatient follow-up, the patient presented to the hospital again with local heat, pain, and swelling at the surgical site on the right hip. The patient had elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) level: 103 (0–15) mm/hour and 192.5 (0–5) mg/L, respectively. Ultrasonography revealed an abscess on the right hip (Fig. 3), and 3-phase bone scan showed no definite osteomyelitis (Fig. 4). Based on these findings, incision, drainage, and debridement were performed on soft tissues. A combination of intravenous ampicillin and sulbactam was administered for 5 weeks after Streptococcus anginosus was identified. ESR and CRP decreased back to normal limits (46 mm/hour and 2.29 mg/dL, respectively). Symptoms improved and the patient was discharged with oral amoxicillin and clavulanate for 2 weeks. She returned to the hospital 2 months after discharge, presenting with heat, pain, and swelling at the surgical site. ESR and CRP levels were elevated again (116 mm/hour and 311.5 mg/dL, respectively). At her last follow-up before presentation she had ESR of 38 mm/hour, and CRP of 4.67 mg/dL, which is within the normal range. A 3-phase bone scan confirmed chronic osteomyelitis at the surgical site, possibly extending to the intramedullary canal (Fig. 5). Radiography showed some callus formation at the fracture site, but still a nonunion could be observed (Fig. 6). A two-stage surgery, including removal of the existing PFNA to treat the infection and stable fixation to treat the nonunion, is generally performed but requires a prolonged hospitalization period. We therefore decided to insert an antibiotic cement-coated intramedullary nail in a one-stage surgery. However, the patient's diaphysis of the femur was too shallow to insert the antibiotic cement-coated intramedullary nail, even when using the smallest femoral intramedullary nail. Stable fixation could not be achieved using an antibiotic cement-coated intramedullary K-wire; thus, we decided to use an antibiotic cement-coated tibial intramedullary nail (Fig. 7). Debridement and cultures from the abscess pocket were performed. Curettage was performed using a long curette on the medullary canal without reaming. The nail was inserted in femur after coating the nail with bone cement (3-g CMW bone cement [2]; DePuy Synthes, Raynham, MA, USA) mixed with antibiotics (vancomycin, 1 g, 2 vials). Interlocking screws were not inserted for the following reasons: 1) the fracture site showed some evidence of healing with little pseudomotion; and 2) the narrow patient's femoral canal contributed to a press fit with antibiotic cement-coated tibial intramedullary nail. Additional cement beads (2) were inserted (Fig. 8). No microorganism growth of any kind was observed in intraoperative cultures. A combination of intravenous ampicillin and sulbactam was used for 5 consecutive weeks because S. anginosus had initially been identified 2 months ago. The patient was restricted from any weight bearing for 6 weeks postoperatively, at which point she was instructed to undergo staged weight bearing. The patient was discharged 5 weeks postoperatively with cefditoren for 2 weeks. At that time, ESR (28 mm/hour) and CRP (2.86 mg/L) had returned within normal range. Follow-up results remained normal and bone union was achieved 4 months postoperatively (Fig. 9). The patient was comfortable, without pain; therefore the antibiotic cement-coated intramedullary nail was not removed. The patient was seen at her 4-year follow-up, using a walker for ambulation because of osteoarthritis of the knee and severe spondylosis. However, she reported no hip pain, and normal ESR and CRP levels were maintained (Fig. 10).

Fig. 1. A 79-year-old with hypertension and osteoporosis presented to the emergency department with right hip pain after slipping. Radiography showed a right atypical femoral subtrochanteric fracture.

Fig. 2. Internal fixation was performed using proximal femoral nail antirotation (PFNA) with autologous iliac crest bone graft, simultaneously, because of a high rate of atypical subtrochanteric fracture nonunion.

Fig. 3. Ultrasonography revealed an abscess on the right hip.

Fig. 4. The 3-phase bone scan showed no definite osteomyelitis.

Fig. 5. At two months after discharge, a 3-phase bone scan confirmed chronic osteomyelitis at the surgical site, possibly extending to the intramedullary canal.

Fig. 6. The X-ray showed some callus formation at the fracture site, but still a nonunion could be observed.

Fig. 7. (A) The smallest tibial intramedullary nail. (B) After antibiotic impregnated cement coating.

Fig. 8. The nail was inserted in femur after coating the nail with bone cement (CMW bone cement, Depuy, 3 g, 2 ea) mixed with antibiotics (Vancomycin, 1 g, 2 vials). Additional cement beads (×2) were inserted.

Fig. 9. Bone union was achieved 4 months postoperatively.

Fig. 10. The patient was seen at her 4-year follow-up, the X-ray shows well maintained without osteomyelitis.

DISCUSSION

Generally, patients with infected nonunions and in situ implants are treated using a certain process: First, the implant is removed, and curettage and debridement are performed using intravenous antibiotics, and/or an additional local antibiotic delivery system, such as antibiotics-impregnated cement beads or spacer. The fracture site must simultaneously be protected using an external fixator or splint/cast. After the infection disappears, the nonunion is treated using a stable internal fixation4,5,6,7,8). The patient requires prolonged hospitalization between those two surgeries. Femoral fractures, especially, leads the patients to become bedridden, which increases the risk for several conditions, including pneumonia, sores, and general weakness. Using an antibiotic cement-coated intramedullary nail was considered to overcome that two-stage operation interval.

The effects of antibiotic cement-coated intramedullary nail are already known. The local concentration of systemic antibiotics is only 20% of the serum concentration and their effect decreases further due to bacterial biofilm. However, when using antibiotic-loaded bone cement, local antibiotic concentrations can be maintained at >200 times the overall concentration, which can lower the systemic concentration of antibiotics, thereby reducing systemic toxicity and side effects. Dead space is also minimized9,10). As other internal fixation, it is expected that the role of internal fixation to treat the original function of nonunion.

Previous studies reported treating patients with osteomyelitis using antibiotic cement-coated intramedullary nails5,7,8,9,10). However, this case shows an attempt to insert a tibial intramedullary nail in the femur. Applying an antibioticloaded bone cement to a conventional femoral intramedullary nail causes the volume to become too large, which requires significant reaming of the femur for insertion, thereby weakening the bone. Conversely, infections may be controlled when bone cement is used without an intramedullary nail, but it can be difficult to successfully treat the nonunion. Therefore, in those cases, an antibiotic cement-coated tibial intramedullary nail could be a highly effective option.

In our case, osteomyelitis occurred because of postoperative infection following a proximal femoral fracture. In cases where nonunion persists and a shallow intramedullary femoral canal is present, using an antibiotic cement-coated tibial intramedullary nail could be an effective option to simultaneously treat patients with osteomyelitis of the femur and achieve bone union.

References

- 1.Patzakis MJ, Zalavras CG. Chronic posttraumatic osteomyelitis and infected nonunion of the tibia: current management concepts. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2005;13:417–427. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200510000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zalavras CG, Patzakis MJ, Holtom P. Local antibiotic therapy in the treatment of open fractures and osteomyelitis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;(427):86–93. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000143571.18892.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beals RK, Bryant RE. The treatment of chronic open osteomyelitis of the tibia in adults. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;(433):212–217. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000150462.41498.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thonse R, Conway J. Antibiotic cement-coated interlocking nail for the treatment of infected nonunions and segmental bone defects. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21:258–268. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e31803ea9e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bharti A, Saroj UK, Kumar V, Kumar S, Omar BJ. A simple method for fashioning an antibiotic impregnated cemented rod for intramedullary placement in infected non-union of long bones. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2016;7(Suppl 2):171–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Struijs PA, Poolman RW, Bhandari M. Infected nonunion of the long bones. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21:507–511. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e31812e5578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Riel RU, Gladden PB. A simple method for fashioning an antibiotic cement-coated interlocking intramedullary nail. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2010;39:18–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roche O, Zabée L, Sirveaux F, Villanueva E, Molé D. Treatment of septic nonunion of long bones: preliminary results of a two-stage procedure. J Bone Joint Surg Br Proc. 2005;87-B:111–112. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lew DP, Waldvogel FA. Osteomyelitis. Lancet. 2004;364:369–379. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16727-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neut D, van de Belt H, van Horn JR, van der Mei HC, Busscher HJ. The effect of mixing on gentamicin release from polymethylmethacrylate bone cements. Acta Orthop Scand. 2003;74:670–676. doi: 10.1080/00016470310018180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]