Abstract

Nitrite and S-nitrosothiols (SNOs) are both byproducts of nitric oxide (NO) metabolism and are proposed to cause vasodilation via activation of soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC). We have previously reported that while SNOs are potent vasodilators at physiological concentrations, nitrite itself only produces vasodilation at supraphysiological concentrations. Here, we tested the hypothesis that sub-vasoactive concentrations of nitrite potentiate the vasodilatory effects of SNOs. Multiple exposures of isolated sheep arteries to S-nitroso-glutathione (GSNO) resulted in a tachyphylactic decreased vasodilatory response to GSNO but not to NO, suggesting attenuation of signaling steps upstream from sGC. Exposure of arteries to 1 μM nitrite potentiated the vasodilatory effects of GSNO in naive arteries and abrogated the tachyphylactic response to GSNO in pre-exposed arteries, suggesting that nitrite facilitates GSNO-mediated activation of sGC. In intact anesthetized sheep and rats, inhibition of NO synthases to decrease plasma nitrite levels attenuated vasodilatory responses to exogenous infusions of GSNO, an effect that was reversed by exogenous infusion of nitrite at sub-vasodilating levels. This study suggests nitrite potentiates SNO-mediated vasodilation via a mechanism that lies upstream from activation of sGC.

Keywords: S-nitrosothiol, nitrite, vasodilation, intracellular NO store

Introduction

Due to its rapid reaction with hemoglobin, nitric oxide (NO) has a very short circulation half-life (merely 2 ms in blood), thus limiting the range of NO itself to paracrine tissues [1; 2]. Nonetheless, endocrine effects of NO have been widely reported [3; 4], implicating the existence of byproducts of NO that retain its bioactivity and are stable enough to circulate systemically [5; 6; 7]. Over the past two decades much research has been focused on determining the chemical identity of these bioactive NO metabolites, with nitrite and S-nitrosothiols (SNOs) receiving the most attention [5; 6; 7; 8; 9; 10; 11; 12; 13].

Nitrite, an anion ubiquitous in both blood and vessel walls, can serve as a source of NO bioactivity with vasodilatory effects [14]. Early work put forth the idea that nitrite’s vasoactivity was due to the ability of deoxyhemoglobin to reduce nitrite to NO [5]. Based on the relative abundance of deoxyhemoglobin in hypoxic tissues, this reaction was proposed to promote vasodilation that would serve to restore adequate O2 delivery [15]. However, more recent work with nitrite suggests that nitrite’s vasodilating properties do not depend solely on the reaction with hemoglobin [16; 17; 18]. The vasodilating effects of nitrite may also be derived from its direct action on vascular smooth muscle cells [17; 19; 20]. The mechanism for these effects remains unclear, although it may involve the conversion of nitrite to NO or some other active NO-adduct within the vascular smooth muscle cell by a number of proposed pathways [9; 17; 19; 20; 21].

S-nitrosothiols are a class of molecules containing NO that has bound to sulfur by replacing the hydrogen of a thiol group. These compounds circulate in blood [22] and cause vasodilation by both NO/cGMP dependent and independent pathways [23]. The NO/cGMP dependent pathway, which appears to be the predominant one [24], involves the activation of soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) by NO within vascular smooth muscle cells [24; 25; 26]. However, the mechanism by which extracellular SNOs, most of which are membrane-impermeable, produce activation of intracellular sGC is still not clear. The following possible mechanisms have been proposed for the cross-membrane vasodilatory signaling of SNOs (Figure S1): 1) SNOs decompose to release free NO either spontaneously or via catalysis by the cell surface protein disulfide isomerase (csPDI) [27; 28], followed by diffusion of the NO into the cell to activate sGC; 2) SNOs S-transnitrosylate thiol groups on the surface of the cell membrane[29; 30] to initiate cross-membrane signaling events that result in transport of the NO moiety into the cell; or SNOs cross the cell membrane after conversion into either 3) membrane-permeable thionitrous acid (HSNO) formed by S-transnitrosation of H2S [31], 4) S-nitroso-L-cysteine (L-cysNO) which can be taken into the cell via the LAT [32; 33], or 5) L-cysNO-glycine formed by hydrolyzation of GSNO via -glutamyl transpeptidase ( -GT) [34] before being taken into the cell through the dipeptide transporters (PEPT2) [35]. Despite decades of interest, no consensus of support has emerged for any one of these pathways.

The membrane permeability and rate of release of NO from SNOs varies depending on the chemical nature of the molecule. For instance, L-cysNO and its stereoisomer D-cysNO decompose to release NO more rapidly than S-nitroso-glutathione (GSNO) [36]. In contrast, L-cysNO can move across plasma membranes via the L-type amino acid transporter (LAT), whereas D-cysNO and especially GSNO are relatively membrane-impermeable [32]. In this study, we tested the above previously-proposed mechanisms for L-cysNO, D-cysNO, and GSNO mediated vasodilation, with results failing to support any of these pathways. However, we find that SNO-mediated vasodilation is potentiated by the presence of nitrite, an interaction that gives rise to novel hypotheses for the vasoactivity of both SNOs and nitrite.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of SNOs and pharmacological compounds

GSNO, L-cysNO, D-cysNO, and their corresponding blank controls were prepared as reported before [37; 38] and described in the Online Supplementary Information (SI). Test compounds were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), and dose information and justification for pharmacological selectivity at those doses are provided in the references shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Compounds tested to influence vasodilatory responses.

| Name | Chemical description | Concentration | Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| ODQ | 1H-[1,2,4] oxadiazolo [4,3-a] quinoxaline-1-one | 10 μM | competitive sGC inhibitor[68] |

| CPTIO | 2-(4-carboxyphenyl)-4,4,5-tetramethyl imidazoline-1-oxyl-3-oxide | 200 μM | membrane-impermeable NO scavenger[43; 69] |

| BCH | 2-Aminobicyclo[2.2.1]heptane-2-carboxylic acid | 10 mM | competitive LAT inhibitor [70] |

| Thr | Threonine | 10 mM | competitive LAT inhibitor[70] |

| Na2S | Na2S | 1 μM | H2S donor[71] |

| PAG | DL-propargyl glycine | 1 mM | H2S synthetase inhibitor[71] |

| GSM | S-methyl-glutathione | 1 mM | -glutamyl transpeptidase ( −GT) inhibitor[72] |

| L-NAME | L-NG-nitro arginine methyl ester | 100 μM | nonspecific NOSs inhibitor [73] |

| HMBA | p-hydroxymercurobenzoic acid | 10 μM | membrane -impermeable thiol modifier[30] |

Experimental animals

All animal procedures were conducted in accordance with procedures that were pre-approved by the LLU Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. In both sheep and rats, blood flow and arterial driving pressure to a hind limb were recorded in response to test compounds so that conductance could be calculated as an index of vasodilation.

Surgical procedures and intra-arterial infusion protocol in sheep

The surgical procedures have been reported before [37; 39] and are described in the SI. The conductance and blood flow of the infused femoral artery, mean arterial blood pressure, and heart rate were recorded. Sheep were randomly divided into three groups: a L-NAME group received L-NAME and SNO; a L-NAME+nitrite group received L-NAME, nitrite, and SNO; a control group received SNO but no L-NAME or nitrite. Hexamethonium was given to block neural influences. L-NAME was administrated intravenously (45 mg/kg bolus) to lower the endogenous nitrite level. Nitrite (1 mM) was infused for 15 min at a rate (1 ml/min) calculated to result in femoral arterial blood nitrite concentrations of ~12.4 μM based on dilution of the infusate in the measured femoral flow[17]. GSNO, D-cysNO, or L-cysNO (5 mM; measured value) was infused at rates of 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, and 0.8 ml/min, increasing every three minutes. A baseline period of 30 min was allowed before the nitrite and SNO infusions. Baseline hemodynamic values before infusion of SNOs in sheep that received L-NAME with or without prior nitrite infusion are shown in Table S1.

Surgical procedures and intra-arterial infusion protocol in rats

The surgical procedures in rats were similar to the sheep experiments mentioned above and described in the SI. Briefly, rats were randomly divided into three groups: a control group received GSNO; a L-NAME group received L-NAME and GSNO; a L-NAME+nitrite group received L-NAME, nitrite, and GSNO. L-NAME (60 mg·kg·−1day−1, T1/2 = 23 hours [40]) or saline (1 ml; for the control group) was injected intraperitoneally 4 days (including the day of experiment) before the surgery. After a stable baseline period of 30 min, saline or nitrite (50 μM in saline) was infused. After another 30 min, GSNO (50 μM) was infused into the lower abdominal aorta at rates of 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, and 0.4 ml/min, increasing every three minutes. Arterial pressure and femoral blood flow were recorded continuously for calculation of femoral artery conductance while GSNO was infused.

Wire myography

Arterial rings (2 mm diameter and 5 mm long) were dissected from a portion of the mesenteric artery supplying the duodenum or from the lateral circumflex branch of the femoral artery of adult ewes. Arterial rings were denuded of endothelium and mounted in organ bath chambers as described previously [37; 38] and described in the SI. Initial wire myography studies of L- and D-cysNO were performed by measuring SNO dose response curves in femoral arteries after constriction with 10 μM phenylephrine. Subsequently, because mesenteric arteries proved to be more sensitive to vasodilation by SNOs and because the dilation of both vessel types was NO/cGMP dependent [38], experiments of GSNO were performed in mesenteric arteries after constriction with 125mM KCl [38]. Test compounds were added to the baths 15 min before the contraction and maintained until the end of the experiments, except for HMBA, a thiol modifier (10 μM) [30], which was incubated with vessels for 30 min and then extensively washed out before contraction. To control for spontaneous changes in tension, changes in vessels treated with inert SNO controls in parallel vessel baths were subtracted from individual experiments before calculation.

Analytical methods

Details of analytical methods including tri-iodide chemiluminescence measurement of nitrogen oxides, ELISA measurement of cGMP, confocal microscopy measurement of intracellular NO, and electron paramagnetic resonance measurement of dinitrosyl iron complexes (DNIC), an intracellular NO-containing molecule [41; 42], are given in the SI.

Statistics and data analysis

Average values are given as mean ±SEM in the text and figures. Two-way ANOVA was used to compare the infusion dose response curves. One-way ANOVA was used to test significance of changes with infusion rates. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc tests or paired t tests were used as appropriate. Statistical analyses were carried out with Prism, v5.0c (Graphpad Software, La Jolla, CA) with significance accepted at p<0.05. Dose response data was quantified by calculating concentrations at one-half maximal response (EC50), an index of sensitivity, and maximal response (Emax), potency of relaxation, by fitting the data to the Gaddum/Schild model in Prism, v5.0c.

Results

Tests of previously proposed mechanisms of cross-membrane vasodilatory signaling by SNOs

In the wire myography studies, removal of the endothelium did not alter dose responses to L- or D-cysNO (Figure S2). Thus, vasodilatory responses did not depend on an intact endothelium and endothelium-denuded vessels were used in subsequent experiments. The competitive sGC inhibitor ODQ shifted the dose response curves of both SNOs to the right (Figure S2 and Table S2, (p<0.05) indicating that the vasodilation pathway is dependent on sGC activation.

To test the role of transmembrane movement of SNOs in mediating vasodilation, dose-response curves of L-cysNO and D-cysNO were compared in isolated sheep femoral arteries. Despite the greater membrane permeability of L-cysNO [32] the two SNOs had similar EC50 and Emax values (Figure S2 and Table S2).

To test whether L- and D-cysNO-mediated vasodilation was brought about by extracellular release of free NO that would then diffuse across the cell membrane to activate sGC, dose response curves were carried out in the presence of CPTIO, a membrane-impermeable NO scavenger [43]. Although CPTIO completely blocked vasodilation by free NO itself (see Figure S5), it only partially attenuated the relaxation effects of L- and D-cysNO, suggesting that the vasodilation by these SNOs is not due entirely to extracellularly released NO.

The role of membrane surface thiols was previously proposed based on the observation that HMBA, a membrane-impermeable compound that binds covalently to thiols, attenuated L-cysNO-mediated vasodilation [30]. However, our finding that L-cysNO is rapidly degraded in the presence of HMBA (Figure S3D) suggests that the attenuation effects might be an artifact in that HMBA actually accelerates the degradation of SNOs and thus should not be used concomitantly. Therefore, our protocol provided for pre-exposure of the vessels to HMBA to block extracellular thiols prior to the addition of SNOs for vasodilation. After washing away unreacted HMBA, vasodilatory responses to either L- or D-cysNO were unchanged (Figure S3A, S3B). These results do not support the involvement of cell membrane surface thiols in the vasorelaxation. However, it is important to note that although HMBA blocked >30% of the extracellular surface thiols (Figure S3C) for a period of time that was longer than required for the wire myography experiments (<60min), a large portion of extracellular thiols was not affected by the HMBA. Therefore, the HMBA tests cannot exclude the involvement of an extracellular thiol.

The role of the LAT was tested by performing dose response curves in the presence of the competitive LAT inhibitors BCH and Thr. Rather than desensitize vasodilation as would be expected if uptake of L-cysNO as an intact molecule was required, these inhibitors both sensitized the vasodilatory effects of L- and D-cysNO (Figure S4 and Table S2), indicating that uptake of SNOs may actually desensitize vasodilation instead.

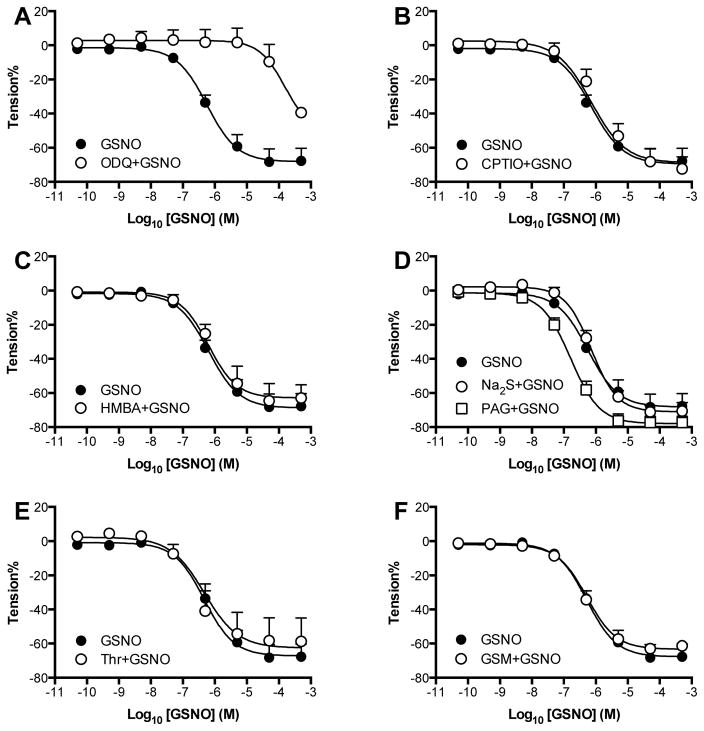

We then performed wire myography experiments with mesenteric arteries using GSNO, which is impermeable to vascular smooth muscle cell membranes but a potent vasodilator nonetheless [38]. Again, as in femoral arteries, ODQ right-shifted the GSNO dose response curve indicating a critical role for the NO/cGMP pathway in GSNO-mediated vasodilation (Figure 1 and Table S3). The membrane-impermeable NO scavenger CPTIO, which abolishes NO-mediated vasodilation (Figure S5), did not alter the responses to GSNO, indicating that the GSNO-mediated vasodilation was not dependent on NO released outside the cell. Likewise, HMBA (impermeable thiol blocker), Thr (competitive LAT inhibitor), and GSM ( −GT inhibitor) did not have any measurable effects suggesting that the relaxation might be independent of membrane surface thiols, LAT, and −GT, respectively (Figure 1, and Table S3). The H2S source Na2S did not potentiate vasodilation, and H2S synthetase inhibitor PAG did not attenuate vasodilation but actually left-shifted the GSNO dose response curves (p=0.0429), indicating that HSNO formed by transnitrosation of H2S by GSNO does not potentiate but may actually attenuate vasodilation.

Figure 1. Tests of previously proposed mechanisms of GSNO-mediated vasodilation.

A) ODQ markedly attenuated vasodilatory effects of GSNO in isolated sheep mesenteric arteries, demonstrating an essential role for the sGC/cGMP pathway. GSNO-mediated vasodilation is not dependent on B) release of free NO outside the cell, because the impermeable NO-scavenger CPTIO had no effect, C) S-transnitrosation of extracellular thiols, as the thiol blocker HMBA had no effect, D) conversion to membrane permeable thionitrous acid (HSNO), as the H2S donor Na2S did not potentiate vasodilation and also the H2S synthase inhibitor PAG even significantly left-shifted the GSNO dose response curve (p=0.043), E) conversion to L-cysNO which can cross the membrane via L-type amino acid transporters (LAT), because the LAT blocker threonine (Thr) had no effect, or F) hydrolyzation by -glutamyl transpeptidase ( -GT) to L-cysNO-gly which can cross the membrane via dipeptide transporters (PEPT2), as the -GT blocker GSM had no effect. N=arterial rings from ≥ 5 animals.

To test the possibility that GSNO-mediated vasodilation might be occurring by real-time activation of L-arginine-dependent NOS within the vascular smooth muscle, wire myography experiments were conducted in the presence of L-NAME, a non-selective NOS inhibitor. L-NAME added 15 min before contraction did not alter GSNO-mediated vasodilation (Figure S6), indicating no detectable role for NOS in GSNO-mediated vasodilation.

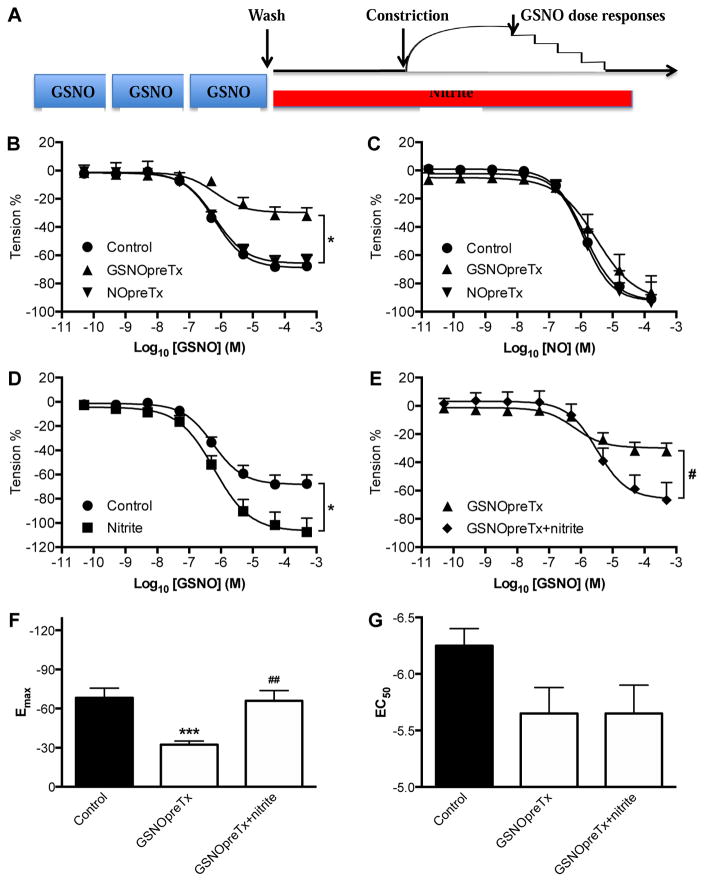

Pre-exposure of arteries to GSNO attenuates vasodilatory responses to GSNO but not NO

The above evidence against the various means by which SNOs might trigger vasodilation led us to experiments designed to further characterize the nature of GSNO-mediated vasodilation. We hypothesized that the mechanism involved signaling steps upstream from sGC activation, and that these steps would be attenuated by repeated exposure of the vessel to SNOs. Consistent with this idea, pretreatment of isolated arteries with GSNO resulted in attenuation of the maximal vasodilatory response to subsequent exposures to GSNO, with no significant effect on the EC50 (Figure 2B, 2F, and 2G) or the basal contractility (Figure S7). In contrast, pretreatment with GSNO did not alter dose responses to NO itself, indicating the attenuating effects of GSNO pretreatment were upstream from sGC activation. In addition, pretreatment of the vessels with NO (Figure 2B), GSH, or blank control of GSNO (Figure S8) instead of GSNO did not alter the GSNO dose-response curve, suggesting that the attenuation response is unique to pretreatment with SNOs as opposed to NO or other species derived from the SNOs. Together with the finding that GSNO mediates vasodilation by the NO/cGMP pathway (Figure 1A and [24]), these results are all consistent with the idea that GSNO-mediated vasodilation involves signaling steps which are attenuated by repeated exposure to GSNO, and that these steps lie upstream from sGC and thus are not involved in vasodilation by NO itself (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. Tachyphylaxis to repeated GSNO exposure, and potentiation by nitrite.

A) Experimental protocol used to study changes in the GSNO dose-response curves of sheep mesenteric artery. Isolated arterial rings were exposed to three 15-minute incubations with 5 μM GSNO (GSNOpreTx) followed by constriction with KCl and then GSNO dose response curves. Comparisons were made to vessels that were not pre-exposed to GSNO (controls) or vessels pre-exposed to 5 μM NO (NOpreTx) instead of GSNO. To test for the effects of nitrite, some GSNOpreTx vessels were exposed to 1μM nitrite for 30 min (GSNOpreTx + nitrite) prior to the constriction. B) Vasodilatory responses to GSNO were diminished after pretreatment with GSNO but not pretreatment with NO. C) NO dose response curves are not affected by pretreatment with GSNO or NO, suggesting that the tachyphylaxis to GSNO-mediated vasodilation does not involve signaling downstream from sGC activation. D) Addition of 1 μM nitrite to control vessels potentiated GSNO-mediated vasodilation in vessels that were not pretreated with GSNO. E) Addition of 1 μM nitrite to GSNO pretreated vessels reversed attenuated vasodilatory responses to GSNO. F) The decrease of Emax (an index of overall vasodilation) by GSNO pretreatment was restored by nitrite. G) EC50 (an index of sensitivity to GSNO) was not significantly changed. N=arterial rings from ≥ 5 animals. *P<0.05, ***P<0.001 for changes relative to Control (no GSNO pretreatment). #P<0.05, ##P<0.01 for changes relative to GSNOpreTx.

We next tested the effects of nitrite on SNO-mediated vasodilation. We observed that the presence of 1 μM nitrite to the vessel bath markedly increased the maximum vasodilation caused by GSNO (Figure 2D, and 2F). In addition, the attenuation of vasodilation caused by pretreatment of the vessels with GSNO was reversed by exposure of the vessels to 1 μM nitrite (Figure 2E, 2F), a concentration more than two orders of magnitude below that required for nitrite itself to cause vasodilation [17].

To test whether the potentiating effects of nitrite were specific to SNO-mediated vasodilation we studied the effect of 1μM nitrite on dose response curves to fasudil, an NO- and sGC-independent vasodilator. Nitrite did not potentiate vasodilation by fasudil, or to NO itself (Figure S10), suggesting that the potentiating effects of nitrite are specific to SNO-mediated vasodilation, and lie upstream from the activation of sGC by intracellular NO.

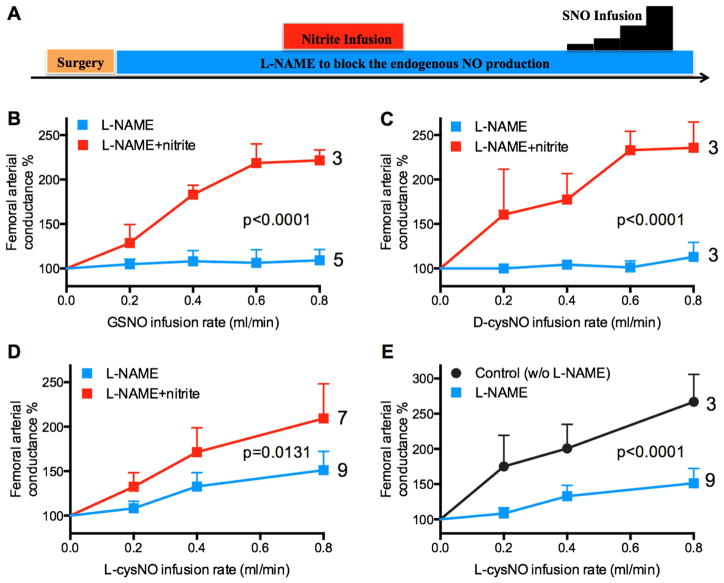

Effect of nitrite on SNO-mediated vasodilation in sheep in vivo

Contrary to the potent vasorelaxation caused by SNO in isolated arteries, we observed no vasodilation in response to GSNO and D-cysNO, and only weak vasodilation in response to L-cysNO infused into the femoral artery of L-NAME-treated sheep [37]. Thus, because NOS inhibition is known to lower circulating nitrite concentrations [44; 45], we hypothesized that the lack of vasodilatory response to SNOs in our previous in vivo experiments [37] was due to decreased nitrite available to facilitate vasodilation by SNOs. We measured basal plasma nitrite concentrations before infusion of L-NAME (0.22±0.02 μM), after infusion of L-NAME (0.12±0.05 μM), and following intravascular infusion of nitrite (0.40±0.17 μM, a level not vasoactive per se in sheep [17]). We observed that the vasodilatory effects of L-cysNO were markedly increased under baseline conditions compared to responses following L-NAME administration. Furthermore, we found that infusions of nitrite to L-NAME-treated animals resulted in markedly increased vasodilatory responses of the femoral artery to infusions of GSNO, D-cysNO, and L-cysNO (Figure 3B, 3C, and 3D). These results in the sheep hind limb are consistent with our myography experiments in that SNO-mediated vasodilation is augmented by nitrite.

Figure 3. Nitrite potentiates vasoactivity of SNOs in the femoral artery of anesthetized sheep.

A) After L-NAME (45 mg·kg−1, iv) infusion and a stable baseline period, nitrite was infused for 15 min into the femoral artery. Then SNO was infused into femoral artery at rates increasing in a step-wise manner. B-D) Prior infusion of nitrite resulted in otherwise absent vasodilatory responses to GSNO (B) and D-cysNO (C) in the femoral vasculature, and augmented L-cysNO-mediated vasodilation (D). E) Vasodilatory responses to L-cysNO were attenuated in animals pre-treated with L-NAME. All y-axes depict normalized changes relative to an average of the femoral arterial conductance measured during the 20 seconds just prior to SNO infusion. Responses are averages from 3 to 9 sheep, with the number studied shown on each curve. p value for vs. L-NAME (two-way ANOVA).

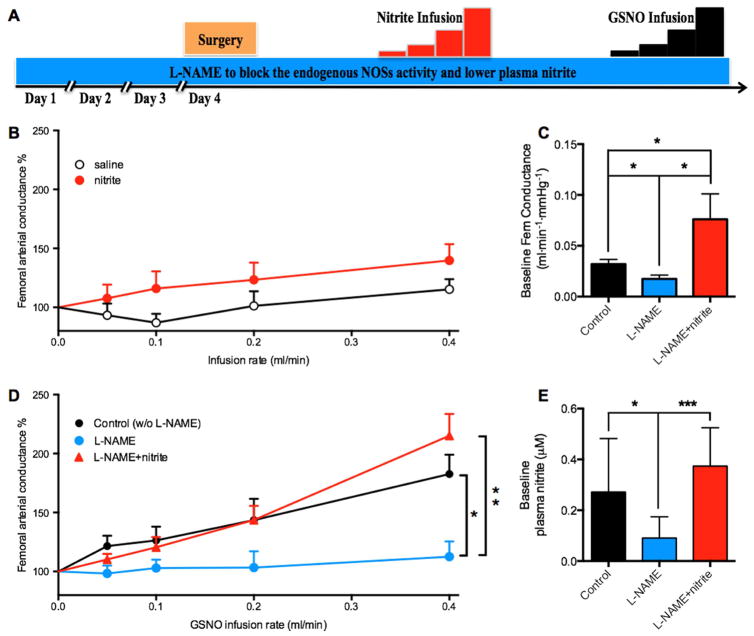

Role of nitrite on GSNO-mediated vasodilation in anesthetized rats

Our previous observation that the sensitivity of sheep arteries to nitrite-mediated vasodilation is nearly 2 orders of magnitude less than that of rat arteries [17] raises the possibility of species-specific pathways of nitrite and SNO-signaling. We therefore further tested the interaction between SNO and nitrite in adult rats. Intraperitoneal injections of L-NAME for four days to lower nitrite levels resulted in a decrease in nitrite concentrations in the wall of the femoral arteries from 0.11±0.01 to 0.07±0.01 μM/mg protein (p=0.0017). The plasma nitrite concentrations were also decreased by L-NAME (from 0.27±0.09 μM to 0.09±0.02 μM) but were restored (to 0.37±0.06 μM) by infusions of nitrite (Figure 4E). In contrast to sheep that were unresponsive to nitrite itself, femoral arterial conductance of the anesthetized rats increased significantly from baseline in response to nitrite infusion (p=0.01), although no significant difference was observed between saline controls and nitrite (p=0.22; Figure 4B). Similar to sheep, the vasodilatory effects of GSNO were absent in rats pretreated with L-NAME, but were restored by infusions of nitrite (Figure 4D). The increased vasodilatory response to GSNO following pretreatment with L-NAME+nitrite could not be explained by a greater baseline vascular tone against which the GSNO could act because the baseline arterial conductances in these animals were already greater than those of controls and greater than those animals treated only with L-NAME (Figure 4C). These results are all consistent with the idea that GSNO-mediated vasodilation involves signaling pathways that are at least partially facilitated by the presence of nitrite.

Figure 4. Effect of L-NAME and nitrite on femoral conductance responses to GSNO in rats.

A) Rats were given L-NAME for 4 days (60 mg·kg−1·day−1, i.p.) to block endogenous NOSs activity and thereby lower plasma nitrite levels. Animals that received nitrite infusions were then compared to those that received no nitrite. Femoral conductance was then recorded while increasing doses of GSNO were infused into the lower abdominal aorta. B) Saline infusion did not increase the femoral arterial conductance (p=0.12), whereas nitrite did (p=0.01), although no significant difference was observed between saline and nitrite (p=0.22). C) L-NAME pretreatment decreased baseline femoral arterial conductance compared to controls (no L-NAME or nitrite), an effect that was reversed by treatment with nitrite. D) Control animals responded to GSNO infusions with increases in femoral vascular conductance. This effect was lost in animals treated with L-NAME to lower nitrite levels, and then restored in L-NAME-treated animals that were also given exogenous nitrite to replenish plasma levels. E) L-NAME pretreatment decreased baseline plasma nitrite concentrations, whereas nitrite infusions returned it to control levels. Average results from 5 or more animals; *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

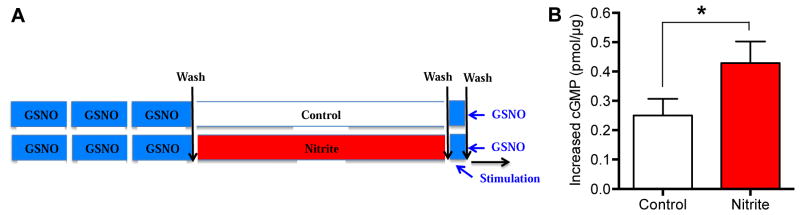

GSNO stimulates higher cGMP levels in the presence of nitrite

To further test the hypothesis that nitrite enhances signaling of GSNO through the sGC pathway, we measured the effects of nitrite on cGMP levels in sheep femoral arteries after exposure to GSNO (Figure 5A). GSNO stimulated greater increases in intracellular cGMP concentrations when nitrite was present (Figure 5B), consistent with the idea that the synergistic effects of GSNO and nitrite involve cGMP-mediated signaling.

Figure 5. Effect of nitrite pretreatment on GSNO-induced cGMP levels in isolated arteries.

A) Samples of sheep femoral arteries were incubated with 5 μM GSNO for three 15 min periods, similar to the treatment that caused tachyphylaxis in Figure 2. They were then incubated with 0 (control) or 1 μM nitrite for 1 h. The increases of cGMP levels in the two groups following 5 min of 5 μM GSNO stimulation were compared. B) GSNO-stimulated increases in cGMP were greater in arteries incubated with nitrite. Average results from 5 or more arteries; *P<0.05; paired t test.

No detectable effect of nitrite on intracellular NO production from GSNO

The observation that GSNO mediates vasodilation by activation of sGC led to the hypothesis that GSNO produces increase in intracellular free NO by mechanisms that are augmented in the presence of nitrite. To test this possibility, we performed experiments to measure the effect of GSNO and nitrite on concentrations of free NO or NO metabolites. First, we found that although low levels of NO are released from GSNO added to PBS (pH 7.4; ~1% NO), there was no increase in the release of NO upon addition of up to 50 μM nitrite (Figure S9), suggesting nitrite does not directly stimulate the release of NO from GSNO. In addition, we observed no difference in free NO release (limit of detection <25 nM) between isolated arteries with and without nitrite pretreatment (Figure S11). Based on recent evidence that a major portion of intracellular NO may be stored in the form of dinitrosyl iron complexes (DNICs)[41; 42], we tested whether DNIC concentrations varied in homogenates of arteries following exposure to GSNO, nitrite + GSNO, or buffer controls. In all cases, DNIC levels were below the lower limit of quantification (1 μM) by EPR (Figure S12D). We also tested for evidence of changes in concentrations of other NO metabolites following exposure of isolated arteries to GSNO with or without nitrite. We did not detect any significant difference in NO metabolites in homogenates of vessels subjected to the above treatments, as measured by triiodide chemiluminescence, which detects NO, nitrite, SNOs, DNICs, and iron nitrosyls, but not nitrate (Figure S12).

Finally, the fluorescent NO probe DAF-FM did not detect a measurable increase of intracellular free NO or its oxidation products (lower limit of detection > 16.5 μM) in isolated smooth muscle cells following GSNO stimulation (Figure S13 and [37]). Thus if GSNO stimulated any increases in intracellular NO, they were below current limits of detection with our methodologies.

Discussion

The current study reveals several important aspects of SNO-mediated vasodilation. Consistent with previous reports [24], we find that the vasodilation occurs primarily via activation of sGC. However, the current experiments fail to support previously proposed pathways (Figure S1) [27; 28; 29; 30; 31; 32; 33; 34; 35]. In addition, our results demonstrate that vasodilation by GSNO involves signaling upstream of sGC that is attenuated by repeated exposure of the vessel to GSNO. We also present the novel observation that sub-vasoactive amounts of nitrite markedly potentiate the vasodilatory effects of SNOs.

It is worth noting that the overall effect of SNOs on vascular tone is likely a complex result of several concomitant processes. For example, vasodilation caused by the decomposition of L-cysNO into NO under simplified wire myography conditions (Figure 2E) may be significantly hindered in vivo due to scavenging of free NO by hemoglobin. Also, uptake of L-cysNO into the cell via the LAT may be followed by the activation of sGC due to NO release [33]. At the same time, the L-cysNO taken into the cell (Figure S4) may cause desensitization to vasodilation via S-transnitrosation of sGC and/or increases in oxidative stress [33; 46; 47]. The relative importance of each of these processes will likely differ between different experimental conditions, animal species, and SNOs. One example of such multiplicity of SNO activities is our observation that all three SNOs exhibited potent vasoactivity in vitro (Figure S4), but only L-cysNO caused vasodilation in vivo in our L-NAME treated sheep (Figure 3). Further study of this multiplicity is needed.

Cross-membrane vasodilatory signaling by SNOs

While a majority of evidence indicates that activation of sGC is a primary factor in SNO-mediated vasodilation, how SNOs signal across the plasma membrane to activate sGC has been unclear. Perhaps the most obvious possibility would be that it is the NO moiety on the SNO that enters the cell to activate sGC. However, this possibility is not supported by a number of our results. First, despite GSNO and D-cysNO being less membrane permeable than L-cysNO [32], there is no difference between the dose response curves of these SNOs (Figure 1, Figure S2 and [38]). Second, NO is released from GSNO at a rate several-fold slower than from L- and D-cysNO [48], yet, the dose response curves of these three SNOs are similar [38], indicating that the release of free NO from the SNOs outside the cell is not a rate-limiting factor. This argument is further supported by the observation that CPTIO, an extracellular NO scavenger, did not modify the dose response curve of GSNO (Figure 1B), providing strong evidence that the release of free extracellular NO is not a requisite factor in SNO-mediated vasodilation. Besides, free NO-mediated vasodilation is of short duration whereas SNO-mediated vasodilation is long lasting (Figure S14). This temporal difference suggests that SNO may activate sGC via direct means or at least via intermediate steps that do not involve the presence of free NO outside the cell. In addition, in contrast to free NO, which diffuses freely and rapidly across cell membranes [2], the membrane-impermeable GSNO is a poor NO donor[36] and thus intracellular NO concentrations are expected to be markedly lower following application of GSNO compared to NO (Figure S13). However, the sensitivity of arteries to these two compounds was similar (Figure 2B, 2C), suggesting that vasodilation by GSNO occurs either at lower intracellular concentrations of free NO, or by utilization of NO from a source other than the applied GSNO per se. Together with the negative results from the tests of several previously proposed mechanisms (Figure S1) by which the NO moiety from the extracellular GSNO enters the cell, and with the novel evidence of a role for nitrite, these results call for the consideration of novel hypotheses for the mechanism of SNO-mediated vasodilation, as discussed below.

Tachyphylactic response to repeated GSNO exposure

In vitro, we find evidence that the vasodilatory response to GSNO is decreased following repeated exposure of the vessel to GSNO (Figure 2B). One possible explanation would be that GSNO exposure has resulted in attenuation of one or more of the components of the sGC-mediated vasodilatory pathway. However, this possibility is not supported by the observation that vasodilatory responses to free NO itself remain unchanged (Figure 2C), indicating the attenuating effects of GSNO pretreatment are upstream of sGC activation, or that GSNO activates sGC by a mechanism that differs from that of free NO. It is also possible that pre-exposure to GSNO results in attenuation of one or more mechanisms that may be involved in the uptake or handling of GSNO in a way that facilitates its activation of sGC. Although the current experiments do not support commonly proposed mechanisms for GSNO-mediated activation of sGC (Figure 1 and S1), the possibility of undiscovered pathways, such as those discussed below, cannot be discounted.

Synergistic vasodilation by nitrite and SNOs

S-nitrosothiols [7; 49] and nitrite [5] have each been argued to be endocrine carriers of NO bioactivity [10]. Intriguingly, although much early emphasis was placed on the conversion of nitrite to NO in blood, evidence from others and us suggests that the vascular wall plays an important role in the bioactivation of nitrite to produce vasodilation [17; 19]. This compartment provides a potential site for cross talk between SNOs and nitrite. Our evidence that the circulating SNOs in blood cross talk with nitrite in the vascular smooth muscle cells to cause vasodilation suggests that SNOs and nitrite may work synergistically rather than independently as endocrine NO adducts. However, it is important to note that the present work does not rule out possible roles for blood in the bioactivity of nitrite or SNOs [5; 7].

Several viable hypotheses can be proposed to explain the novel interaction observed between SNOs and nitrite. For example, endocytotic activity is known to be particularly high in the plasma membrane of vascular smooth muscle cells[50], and thus it is possible that GSNO (and other SNOs) are taken into the vascular smooth muscle cell via endocytosis. A targeted delivery of GSNO to cytosolic sGC via endocytotic vesicles would be consistent with our evidence of no involvement of extracellular free NO in GSNO-mediated vasodilation, and with our observation of similar potencies of SNOs with varying degrees of membrane permeability. In addition, budding of endocytotic vesicles is facilitated by dynamin, a GTPase that is activated by S-nitrosation[51]. Depletion of active dynamin could explain the tachyphylactic response to repeated GSNO exposure, and the ability of nitrite to play a role in S-nitrosation of membrane-associated proteins via nitrated lipid intermediates[52; 53] would constitute a model consistent with the results of this study.

Another possibility involves a role for oxidative stress in response to exposure of cells to SNOs. Our observation of a diminished vasodilatory response following repeated exposure of arteries to GSNO is reminiscent of the more widely known tolerance effect that develops as a result of repeated exposure to organic nitrates such as nitroglycerin. Although the mechanism for such tolerance is still not fully understood, stimulation of oxidative stress that would serve to dampen vasodilation is proposed to play a role[54; 55]. Depletion of intracellular antioxidative reserves could explain the tachyphylactic response to repeated GSNO exposure, and the known ability of nitrite to attenuate reactive oxygen species production[56; 57; 58], would also be consistent with the current results.

A third possible hypothesis would propose that SNOs stimulate the release of NO or an NO equivalent from a preformed intracellular store in vascular smooth muscle cells (Figure S15). The existence of preformed intracellular NO stores has been appreciated for over three decades, beginning with the observation that endothelium-denuded vessels relax in response to light [59; 60], and that this phenomenon involves activation of sGC [61; 62]. Similar to our findings for SNO-mediated vasodilation, a tachyphylactic phenomenon is observed upon repeated exposure of the arteries to light [63; 64]. Nitrite itself is unlikely to be more than a precursor for the production of more bioactive NO adducts, as supraphysiological concentrations of nitrite are required in order to stimulate vasodilation in isolated sheep arteries [17]. However, by reacting with a number of metal-containing enzymes found in vascular smooth muscle cells [65], nitrite can serve as a source of NO adducts, such as SNOs and DNICs, that may serve as a depot form of stored NO bioactivity. SNOs have been implicated as the source of intracellular NO that mediates photorelaxation [66]. However, our in vitro results offer little support for this possibility since inhibition of cellular uptake of SNOs did not attenuate but instead facilitated the vasodilation (Figure 1D and Figure S4 C-F). DNICs, which have recently been proposed to serve as a major intracellular NO adduct [42], are capable of activating sGC [67]. However, as demonstrated by our attempts to measure DNICs in arteries (Figure S12D), more sensitive assay methods are needed to explore this possibility further. It is also not known how extracellular SNOs might interact with the cell to promote activation of an intracellular NO store.

These and other possible explanations for the synergistic effects of nitrite and SNOs warrant further studies that may lead to a deeper understanding of how endothelium- and sGC-mediated vasodilation is regulated.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table S1. Hemodynamic values before infusion of SNOs in L-NAME administrated sheep with or without prior nitrite infusion.

Supplementary Table S2. EC50 values of L-cysNO and D-cysNO with and without factors affecting vasodilation of ovine femoral arterial rings (n⩾5).

Supplementary Table S3. EC50 and Emax values of GSNO in the absence and presence of several compounds in sheep mesenteric arteries (n⩾5).

Supplementary Figure S1. Schematic of five previously proposed mechanisms for the cross-membrane vasodilatory signaling of SNOs: (1) SNOs decompose, either spontaneously or via catalysis by the cell surface protein disulfide isomerase (csPDI), into free NO outside the cell that then diffuses into the cell to activate sGC; (2) SNOs S-transnitrosylate thiol groups on the surface of the cell membrane to initiate cross-membrane signaling events that result in free intracellular NO; SNOs enter the cell membrane after conversion into (3) membrane-permeable thionitrous acid (HSNO) formed by S-transnitrosation of H2S, (4) L-cysNO which can be taken into the cell via the L-type amino acid transporter (LAT), or (5) L-cysNO-gly formed by hydrolyzation of GSNO via -glutamyl transpeptidase ( -GT) before being taken into the cell through the dipeptide transporters (PEPT2). Intracellular SNO (HSNO, L-cysNO, or L-cysNO-gly) releases NO to activate sGC and cause vasodilation.

Supplementary Figure S2. Tests for the role of the NO/cGMP pathway, the endothelium, and extracellularly released NO in L-cysNO- and D-cysNO-mediated vasodilation in isolated sheep femoral arteries (n=5). Arterial strips were denuded of endothelium (except in C and D), and were constricted with phenylephrine followed by cumulative exposure to L-cysNO (A, C, E) or D-cysNO (B, D, F) in the absence and presence of ODQ (A, B), endothelium (C, D), or CPTIO (E, F). A, B) ODQ right-shifts the dose response curves of both L- and D-cysNO. C, D) Endothelium-denudation does not affect L- or D-cysNO mediated vasorelaxation. E, F) CPTIO decreases the Emax of the dose response curves of both L- and D-cysNO. * p<0.05, paired t tests.

Supplementary Figure S3. Role of thiols located on the extracellular plasma membrane in L-cysNO- and D-cysNO-mediated vasodilation (n≥5 except C). Isolated sheep femoral arterial strips were incubated with the membrane-impermeable thiol modifier HMBA for 30 min to block the thiols on the surface of the plasma membrane. Following incubation, the arterial strips were extensively washed and then constricted with phenylephrine. Relaxation responses of arterial strips with and without HMBA pretreatment to L- (A) or D-cysNO (B) are compared, and show no effect of HMBA treatment. C) Blocking effects of HMBA on membrane surface thiols in isolated arterial segments as a function of time post-treatment (n=4). Sheep femoral arterial segments were incubated with HMBA (10μM) for 30 min and the quantity of the membrane surface thiols was measured by Ellman’s test[77] at specified time points before (control) and after (posTx) the incubation. Concentration was calculated by dividing the quantity by wet tissue weight. * for p<0.05 vs control. Extracellular thiols were decreased by more than 30% for at least 1h following HMBA treatment. Membrane surface thiol concentrations were significantly elevated 200 min after treatment, for reasons yet unknown. D) HMBA markedly accelerates the degradation of L-cysNO in PBS suggesting that HMBA is a SNO-depleting agent, which is why we chose to wash it out of the vessel bath prior to addition of the SNOs.

Supplementary Figure S4. Role of cellular uptake via the L-type amino acid transporter LAT in L- and D-cysNO-mediated vasodilation in isolated femoral arteries (n≥5). A,B) effects of LAT inhibitors BCH and Thr on the EC50 of L- and D-cysNO. EC50 of GSNO dose response curve in isolated femoral arteries is also shown for comparison. C, D, E, F) dose response curves of L- and D-cysNO in the absence and presence of BCH and Thr. LAT inhibitors BCH and Thr not only fail to cause a right-shift, as would be expected if the LAT played a role, but even left-shift the dose response curves of L- and D-cysNO indicating that uptake of SNO as an intact entity is not a prerequisite for its vasodilation, but may actually suppress vasodilatory responses to extracellular SNOs. *p<0.05, One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni test.

Supplementary Figure S5. Tests of the effectiveness of the membrane-impermable NO scavenger CPTIO (n=4). CPTIO abolishes free NO-mediated vasodilation, indicating that CPTIO offers an effective test of whether SNO-mediated vasodilation occurs by release of NO from the SNO outside the cell.

Supplementary Figure S6. Tests for the role of vascular NOSs in GSNO-mediated vasodilation in isolated sheep mesenteric arteries (n=5). The non-selective NOSs inhibitor L-NAME does not alter GSNO-mediated vasodilation.

Supplementary Figure S7. Effects of repeated GSNO pretreatment on contractile tension achieved prior to GSNO dose response experiments, demonstrating that GSNO pretreatment did not affect (p=0.85) the absolute contractile tension of the vessels before GSNO dose responses were determined. Average plateau tension of over 18 segments from 6 sheep is shown.

Supplementary Figure S8. The effects of GSH and blank control of GSNO (BGSNO) pretreatment on GSNO-mediated vasodilation (n=5). BGSNO is the blank control of GSNO, and was made from acidified glutathione and nitrate (instead of nitrite), which do not react with one another to produce GSNO. Experiments were performed in the same manner as in Fig 2A.

Supplementary Figure S9. In vitro test for the possibility that nitrite stimulates the release of NO from GSNO. Tests were performed in the absence (A) and presence (B) of arteries. Nitrite concentrations as high as 50 μM do not increase the rate of release of NO from GSNO in PBS (pH 7.4) in a purge vessel in line with a chemiluminescence NO analyzer. A representative trace of three similar experiments is shown.

Supplementary Figure S10. Effects of nitrite on NO and NO-independent vasodilation in isolated sheep arteries (n=5). A) In contrast to the potentiating effect of nitrite on GSNO-mediated vasodilation (Figure 2E) nitrite does not alter NO-mediated vasodilation. B) Nitrite does not alter vasodilation by the non-sGC-dependent pathway of ROCK2 inhibition by fasudil.

Supplementary Figure S11. Measurements seeking to detect free NO released from isolated arteries following stimulation by GSNO. A) Experimental protocol. Isolated sheep femoral arteries were exposed to GSNO for 45 min to achieve tachyphylaxis, and then exposed to HEPES buffer (group a) or nitrite (group b) to abrogate the tachyphylaxis. B, C ) Representative traces of NO signals measured by chemiluminescence in a purge vessel filled with PBS (pH=7.4). B) 50 μM GSNO was injected into 20 ml PBS containing 0.5 ml of tissue homogenate (4 μg/ml protein) from group a or b. The NO signals are not significantly different between vessel groups, suggesting that if GSNO stimulates the release of free NO,from a preformed store it is below the limit of detection by this method (~5 to 25 nM). C) NO sensitivity of the method in the absence and presence of tissue homogenates. Different concentrations of NO were injected into 20ml PBS in the absence and presence of 0.5ml of homogenate from arteries without treatment. The NO sensitivity was not altered by the tissue homogenates, indicating that homogenates do not significantly scavenge NO in the purge vessel, and in both cases the limit of sensitivity was between 5 and 25 nM NO. A representative trace of three similar experiments is shown. Similar results were obtained in experiments performed with isolated artery instead of its homogenate.

Supplement Figure S12. Characterization of changes in intracellular NO metabolite concentrations in isolated sheep femoral arteries following treatment with GSNO and/or nitrite. A) Experimental protocol. Isolated sheep femoral arteries were exposed to GSNO (to cause tachyphylaxis) or HEPES buffer (vehicle controls) for 45 min, then to nitrite (which abrogates tachyphylaxis) or HEPES for 60 min, followed by incubation with GSNO (5 or 45 min) or HEPES. Vessels were then assayed for changes in NO metabolites (NOx) and DNIC concentrations. B) NOx concentrations measured by tri-iodide based chemiluminescence showed no significant difference between different treatments. C) Signals of mononuclear DNIC standards measured by EPR demonstrate sensitivity to as low as 1 μM. D) Representative DNIC signals in homogenate (group O). The DNIC signals from the samples of all groups were under the lower limit of quantification (1 μM), indicating that if mononuclear DNICs play a role in GSNO-mediated signal transduction, the intracellular concentrations are below 1 μM (n≥4).

Supplementary Figure S13. Increase in intracellular NO induced by GSNO (A) and free NO (B). (n≥6) DAF-FM was loaded into the smooth muscle cells as a fluorescence probe for measurement of intracellular NO. Ratio of fluorescence at 30 min after stimulation to that before stimulation (F30/F0) is shown. A) Stimulation with GSNO did not cause any detectable increase in intracellular free NO (or its oxidation products) in isolated smooth muscle cells. B) A significant increase in F30/F0 (index for intracellular NO) was not measured at as high as 16.5 μM NO, indicating low sensitivity of the method. * p<0.05, One-way ANOVA.

Supplementary Figure S14. Representative wire myography dose response curves to GSNO and NO in isolated sheep femoral arterial strips. GSNO mediated long lasting vasodilation, whereas NO-mediated vasodilation disappeared within 4 min, indicating GSNO-mediated vasodilation is different from that of free NO.

Supplementary Figure S15. Working model of the postulated intracellular NOx store. NO metabolites SNO and NO2− circulate systemically. NO2− contributes to a store of NO bioactivity within the vascular smooth muscle cell (intracellular NOx store). Extracellular SNO causes sGC-dependent vasodilation by stimulating NO equivalent (less likely to be free NO per se) release from the intracellular NOx store. The means by which the SNO signal is transduced across the cell membrane remains unknown, as does the exact chemical nature of the NOx store itself.

Highlights.

SNO-mediated vasodilation is attenuated if the arteries were pre-exposed to SNO

SNO-mediated vasodilation is attenuated by inhibition of nitric oxide synthases

Sub-vasoactive amounts of nitrite potentiates SNO-mediated vasodilation

SNO-mediated vasodilation may involve a NO store that is depletable and replenishable

Acknowledgments

Sources of funding

These experiments were supported by NIH Grants R01HL95973 (ABB), PO1 HD-31226 (LDL), R03HD069746 (SMW), and NSF Grant MRI-DBI 0923559 (SMW).

The authors acknowledge the expert technical assistance of Shannon L. Bragg and Monica Romero.

Footnotes

Disclosure

Dr. Power is listed as a co-inventor on a NIH patent for the use of inhaled nitrite for cardiovascular conditions. The remaining authors report no conflicts.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Liu X, Miller MJ, Joshi MS, Sadowska-Krowicka H, Clark DA, Lancaster JR., Jr Diffusion-limited reaction of free nitric oxide with erythrocytes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(30):18709–18713. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.30.18709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas DD. Breathing new life into nitric oxide signaling: A brief overview of the interplay between oxygen and nitric oxide. Redox Biol. 2015;5:225–233. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stamler JS, Reynolds JD, Hess DT. Endocrine nitric oxide bioactivity and hypoxic vasodilation by inhaled nitric oxide. Circ Res. 2012;110(5):652–654. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.263996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fox-Robichaud A, Payne D, Hasan SU, Ostrovsky L, Fairhead T, Reinhardt P, Kubes P. Inhaled NO as a viable antiadhesive therapy for ischemia/reperfusion injury of distal microvascular beds. J Clin Invest. 1998;101(11):2497–2505. doi: 10.1172/JCI2736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cosby K, Partovi KS, Crawford JH, Patel RP, Reiter CD, Martyr S, Yang BK, Waclawiw MA, Zalos G, Xu X, Huang KT, Shields H, Kim-Shapiro DB, Schechter AN, Cannon RO, 3rd, Gladwin MT. Nitrite reduction to nitric oxide by deoxyhemoglobin vasodilates the human circulation. Nat Med. 2003;9(12):1498–1505. doi: 10.1038/nm954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rassaf T, Preik M, Kleinbongard P, Lauer T, Heiss C, Strauer BE, Feelisch M, Kelm M. Evidence for in vivo transport of bioactive nitric oxide in human plasma. J Clin Invest. 2002;109(9):1241–1248. doi: 10.1172/JCI14995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jia L, Bonaventura C, Bonaventura J, Stamler JS. S-nitrosohaemoglobin: A dynamic activity of blood involved in vascular control. Nature. 1996;380(6571):221–226. doi: 10.1038/380221a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang R, Hess DT, Qian Z, Hausladen A, Fonseca F, Chaube R, Reynolds JD, Stamler JS. Hemoglobin betaCys93 is essential for cardiovascular function and integrated response to hypoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(20):6425–6430. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1502285112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Totzeck M, Hendgen-Cotta UB, Luedike P, Berenbrink M, Klare JP, Steinhoff HJ, Semmler D, Shiva S, Williams D, Kipar A, Gladwin MT, Schrader J, Kelm M, Cossins AR, Rassaf T. Nitrite regulates hypoxic vasodilation via myoglobin-dependent nitric oxide generation. Circulation. 2012;126(3):325–334. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.087155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gladwin MT, Schechter AN. NO contest: nitrite versus S-nitroso-hemoglobin. Circ Res. 2004;94(7):851–855. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000126697.64381.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allen BW, Stamler JS, Piantadosi CA. Hemoglobin, nitric oxide and molecular mechanisms of hypoxic vasodilation. Trends Mol Med. 2009;15(10):452–460. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Isbell TS, Sun CW, Wu LC, Teng XJ, Vitturi DA, Branch BG, Kevil CG, Peng N, Wyss JM, Ambalavanan N, Schwiebert L, Ren JX, Pawlik KM, Renfrow MB, Patel RP, Townes TM. SNO-hemoglobin is not essential for red blood cell-dependent hypoxic vasodilation. Nat Med. 2008;14(7):773–777. doi: 10.1038/nm1771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gladwin MT, Shelhamer JH, Schechter AN, Pease-Fye ME, Waclawiw MA, Panza JA, Ognibene FP, Cannon RO. Role of circulating nitrite and S-nitrosohemoglobin in the regulation of regional blood flow in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(21):11482–11487. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.21.11482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Omar SA, Webb AJ, Lundberg JO, Weitzberg E. Therapeutic effects of inorganic nitrate and nitrite in cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. J Intern Med. 2016;279(4):315–336. doi: 10.1111/joim.12441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gladwin MT, Raat NJ, Shiva S, Dezfulian C, Hogg N, Kim-Shapiro DB, Patel RP. Nitrite as a vascular endocrine nitric oxide reservoir that contributes to hypoxic signaling, cytoprotection, and vasodilation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291(5):H2026–2035. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00407.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blood AB, Schroeder HJ, Terry MH, Merrill-Henry J, Bragg SL, Vrancken K, Liu TM, Herring JL, Sowers LC, Wilson SM, Power GG. Inhaled Nitrite Reverses Hemolysis-Induced Pulmonary Vasoconstriction in Newborn Lambs Without Blood Participation. Circulation. 2011;123(6):605–U136. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu T, Schroeder HJ, Barcelo L, Bragg SL, Terry MH, Wilson SM, Power GG, Blood AB. Role of blood and vascular smooth muscle in the vasoactivity of nitrite. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2014;307(7):H976–986. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00138.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Truong GT, Schroder HJ, Liu T, Zhang M, Kanda E, Bragg S, Power GG, Blood AB. Role of nitrite in regulation of fetal cephalic circulation in sheep. J Physiol. 2014;592(Pt 8):1785–1794. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.269340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li H, Cui H, Kundu TK, Alzawahra W, Zweier JL. Nitric oxide production from nitrite occurs primarily in tissues not in the blood: critical role of xanthine oxidase and aldehyde oxidase. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(26):17855–17863. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801785200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dalsgaard T, Simonsen U, Fago A. Nitrite-dependent vasodilation is facilitated by hypoxia and is independent of known NO-generating nitrite reductase activities. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292(6):H3072–3078. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01298.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu XP, Tong JJ, Zweier JR, Follmer D, Hemann C, Ismail RS, Zweier JL. Differences in oxygen-dependent nitric oxide metabolism by cytoglobin and myoglobin account for their differing functional roles. Febs Journal. 2013;280(15):3621–3631. doi: 10.1111/febs.12352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hogg N. Biological chemistry and clinical potential of S-nitrosothiols. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;28(10):1478–1486. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00248-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hogg N. The biochemistry and physiology of S-nitrosothiols. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2002;42:585–600. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.42.092501.104328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lies B, Groneberg D, Gambaryan S, Friebe A. Lack of effect of ODQ does not exclude cGMP signalling via NO-sensitive guanylyl cyclase. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;170(2):317–327. doi: 10.1111/bph.12275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dierks EA, Burstyn JN. Nitric oxide (NO), the only nitrogen monoxide redox form capable of activating soluble guanylyl cyclase. Biochem Pharmacol. 1996;51(12):1593–1600. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(96)00078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moro MA, Russel RJ, Cellek S, Lizasoain I, Su Y, Darley-Usmar VM, Radomski MW, Moncada S. cGMP mediates the vascular and platelet actions of nitric oxide: confirmation using an inhibitor of the soluble guanylyl cyclase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(4):1480–1485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Broniowska KA, Diers AR, Hogg N. S-nitrosoglutathione. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1830(5):3173–3181. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Y, Hogg N. The mechanism of transmembrane S-nitrosothiol transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(21):7891–7896. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401167101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramachandran N, Root P, Jiang XM, Hogg PJ, Mutus B. Mechanism of transfer of NO from extracellular S-nitrosothiols into the cytosol by cell-surface protein disulfide isomerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(17):9539–9544. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171180998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kowaluk EA, Fung HL. Spontaneous liberation of nitric oxide cannot account for in vitro vascular relaxation by S-nitrosothiols. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1990;255(3):1256–1264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davisson RL, Travis MD, Bates JN, Lewis SJ. Hemodynamic effects of L- and D-S-nitrosocysteine in the rat. Stereoselective S-nitrosothiol recognition sites. Circ Res. 1996;79(2):256–262. doi: 10.1161/01.res.79.2.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoque A, Bates JN, Lewis SJ. In vivo evidence that L-S-nitrosocysteine may exert its vasodilator effects by interaction with thiol residues in the vasculature. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;384(2–3):169–172. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00686-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Filipovic MR, Miljkovic J, Nauser T, Royzen M, Klos K, Shubina T, Koppenol WH, Lippard SJ, Ivanovic-Burmazovic I. Chemical characterization of the smallest S-nitrosothiol, HSNO; cellular cross-talk of H2S and S-nitrosothiols. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134(29):12016–12027. doi: 10.1021/ja3009693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Riego JA, Broniowska KA, Kettenhofen NJ, Hogg N. Activation and inhibition of soluble guanylyl cyclase by S-nitrosocysteine: involvement of amino acid transport system L. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47(3):269–274. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lipton AJ, Johnson MA, Macdonald T, Lieberman MW, Gozal D, Gaston B. S-nitrosothiols signal the ventilatory response to hypoxia. Nature. 2001;413(6852):171–174. doi: 10.1038/35093117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brahmajothi MV, Sun NZ, Auten RL. S-nitrosothiol transport via PEPT2 mediates biological effects of nitric oxide gas exposure in macrophages. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2013;48(2):230–239. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0305OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matsunaga K, Furchgott RF. Interactions of Light and Sodium-Nitrite in Producing Relaxation of Rabbit Aorta. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1989;248(2):687–695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mehta B, Begum G, Joshi NB, Joshi PG. Nitric oxide-mediated modulation of synaptic activity by astrocytic P2Y receptors. J Gen Physiol. 2008;132(3):339–349. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200810043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu T, Schroeder HJ, Zhang M, Wilson SM, Terry MH, Longo LD, Power GG, Blood AB. S-nitrosothiols dilate the mesenteric artery more potently than the femoral artery by a cGMP and L-type calcium channel-dependent mechanism. Nitric Oxide. 2016;58:20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2016.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu T, Schroeder HJ, Wilson SM, Terry MH, Longo LD, Power GG, Blood AB. Local and systemic vasodilatory effects of low molecular weight S-nitrosothiols. Free Radic Biol Med. 2015;91:215–223. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ignarro LJ, Lippton H, Edwards JC, Baricos WH, Hyman AL, Kadowitz PJ, Gruetter CA. Mechanism of vascular smooth muscle relaxation by organic nitrates, nitrites, nitroprusside and nitric oxide: evidence for the involvement of S-nitrosothiols as active intermediates. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1981;218(3):739–749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tsikas D, Sandmann J, Rossa S, Gutzki FM, Frolich JC. Investigations of S-transnitrosylation reactions between low- and high-molecular-weight S-nitroso compounds and their thiols by high-performance liquid chromatography and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Anal Biochem. 1999;270(2):231–241. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fernhoff NB, Derbyshire ER, Underbakke ES, Marletta MA. Heme-assisted S-nitrosation desensitizes ferric soluble guanylate cyclase to nitric oxide. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(51):43053–43062. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.393892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sayed N, Baskaran P, Ma X, van den Akker F, Beuve A. Desensitization of soluble guanylyl cyclase, the NO receptor, by S-nitrosylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(30):12312–12317. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703944104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kleinbongard P, Dejam A, Lauer T, Rassaf T, Schindler A, Picker O, Scheeren T, Godecke A, Schrader J, Schulz R, Heusch G, Schaub GA, Bryan NS, Feelisch M, Kelm M. Plasma nitrite reflects constitutive nitric oxide synthase activity in mammals. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;35(7):790–796. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00406-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lauer T, Preik M, Rassaf T, Strauer BE, Deussen A, Feelisch M, Kelm M. Plasma nitrite rather than nitrate reflects regional endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity but lacks intrinsic vasodilator action. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(22):12814–12819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221381098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pawloski JR, Hess DT, Stamler JS. Export by red blood cells of nitric oxide bioactivity. Nature. 2001;409(6820):622–626. doi: 10.1038/35054560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Furchgott RF, Ehrreich SJ, Greenblatt E. The photoactivated relaxation of smooth muscle of rabbit aorta. J Gen Physiol. 1961;44:499–519. doi: 10.1085/jgp.44.3.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Furchgott RF, Sleator W, Mccaman MW, Elchlepp J. Relaxation of Arterial Strips by Light, and the Influence of Drugs on This Photodynamic Effect. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1955;113(1):22–23. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kubaszewski E, Peters A, McClain S, Bohr D, Malinski T. Light-activated release of nitric oxide from vascular smooth muscle of normotensive and hypertensive rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;200(1):213–218. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lovren F, Triggle CR. Involvement of nitrosothiols, nitric oxide and voltage-gated K+ channels in photorelaxation of vascular smooth muscle. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;347(2–3):215–221. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00095-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Venturini CM, Palmer RMJ, Moncada S. Vascular Smooth-Muscle Contains a Depletable Store of a Vasodilator Which Is Light-Activated and Restored by Donors of Nitric-Oxide. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;266(3):1497–1500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Muller B, Kleschyov AL, Alencar JL, Vanin A, Stoclet JC. Nitric oxide transport and storage in the cardiovascular system. Nitric Oxide: Novel Actions, Deleterious Effects and Clinical Potential. 2002;962:131–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kubaszewski E, Peters A, Mcclain S, Bohr D, Malinski T. Light-Activated Release of Nitric-Oxide from Vascular Smooth-Muscle of Normotensive and Hypertensive Rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;200(1):213–218. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Furchgott RF, Jothianandan D. Endothelium-Dependent and Endothelium-Independent Vasodilation Involving Cyclic-Gmp - Relaxation Induced by Nitric-Oxide, Carbon-Monoxide and Light. Blood Vessels. 1991;28(1–3):52–61. doi: 10.1159/000158843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim-Shapiro DB, Gladwin MT. Mechanisms of nitrite bioactivation. Nitric Oxide. 2014;38:58–68. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Samouilov A, Kuppusamy P, Zweier JL. Evaluation of the magnitude and rate of nitric oxide production from nitrite in biological systems. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1998;357(1):1–7. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.0785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rodriguez J, Maloney RE, Rassaf T, Bryan NS, Feelisch M. Chemical nature of nitric oxide storage forms in rat vascular tissue. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(1):336–341. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0234600100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hickok JR, Sahni S, Shen H, Arvind A, Antoniou C, Fung LWM, Thomas DD. Dinitrosyliron complexes are the most abundant nitric oxide-derived cellular adduct: biological parameters of assembly and disappearance. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51(8):1558–1566. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mokh VP, Poltorakov AP, Serezhenkov VA, Vanin AF. On the nature of a compound formed from dinitrosyl-iron complexes with cysteine and responsible for a long-lasting vasorelaxation. Nitric Oxide. 2010;22(4):266–274. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rahmanto YS, Kalinowski DS, Lane DJR, Lok HC, Richardson V, Richardson DR. Nitrogen Monoxide (NO) Storage and Transport by Dinitrosyl-Dithiol-Iron Complexes: Long-lived NO That Is Trafficked by Interacting Proteins. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(10):6960–6968. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R111.329847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Anand P, Stamler JS. Enzymatic mechanisms regulating protein S-nitrosylation: implications in health and disease. J Mol Med (Berl) 2012;90(3):233–244. doi: 10.1007/s00109-012-0878-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vanin AF. Dinitrosyl iron complexes with thiol-containing ligands as a “working form” of endogenous nitric oxide. Nitric Oxide. 2016;54:15–29. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2016.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu T, Schroeder HJ, Barcelo L, Bragg SL, Terry MH, Wilson SM, Power GG, Blood AB. Role of blood and vascular smooth muscle in the vasoactivity of nitrite. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2014 doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00138.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Avontuur JAM, Buijk SLCE, Bruining HA. Distribution and metabolism of N-G-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester in patients with septic shock. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;54(8):627–631. doi: 10.1007/s002280050525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schrammel A, Behrends S, Schmidt K, Koesling D, Mayer B. Characterization of 1H-[1,2,4]oxadiazolo[4,3-a]quinoxalin-1-one as a heme-site inhibitor of nitric oxide-sensitive guanylyl cyclase. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;50(1):1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hogg N, Singh RJ, Joseph J, Neese F, Kalyanaraman B. Reactions of nitric oxide with nitronyl nitroxides and oxygen: prediction of nitrite and nitrate formation by kinetic simulation. Free Radic Res. 1995;22(1):47–56. doi: 10.3109/10715769509147527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li S, Whorton AR. Functional characterization of two S-nitroso-L-cysteine transporters, which mediate movement of NO equivalents into vascular cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292(4):C1263–1271. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00382.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Stein A, Bailey SM. Redox Biology of Hydrogen Sulfide: Implications for Physiology, Pathophysiology, and Pharmacology. Redox Biol. 2013;1(1):32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hogg N, Singh RJ, Konorev E, Joseph J, Kalyanaraman B. S-nitrosoglutathione as a substrate for gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase. Biochem J. 1997;323:477–481. doi: 10.1042/bj3230477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vitecek J, Lojek A, Valacchi G, Kubala L. Arginine-based inhibitors of nitric oxide synthase: therapeutic potential and challenges. Mediators Inflamm. 2012;2012:318087. doi: 10.1155/2012/318087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table S1. Hemodynamic values before infusion of SNOs in L-NAME administrated sheep with or without prior nitrite infusion.

Supplementary Table S2. EC50 values of L-cysNO and D-cysNO with and without factors affecting vasodilation of ovine femoral arterial rings (n⩾5).

Supplementary Table S3. EC50 and Emax values of GSNO in the absence and presence of several compounds in sheep mesenteric arteries (n⩾5).

Supplementary Figure S1. Schematic of five previously proposed mechanisms for the cross-membrane vasodilatory signaling of SNOs: (1) SNOs decompose, either spontaneously or via catalysis by the cell surface protein disulfide isomerase (csPDI), into free NO outside the cell that then diffuses into the cell to activate sGC; (2) SNOs S-transnitrosylate thiol groups on the surface of the cell membrane to initiate cross-membrane signaling events that result in free intracellular NO; SNOs enter the cell membrane after conversion into (3) membrane-permeable thionitrous acid (HSNO) formed by S-transnitrosation of H2S, (4) L-cysNO which can be taken into the cell via the L-type amino acid transporter (LAT), or (5) L-cysNO-gly formed by hydrolyzation of GSNO via -glutamyl transpeptidase ( -GT) before being taken into the cell through the dipeptide transporters (PEPT2). Intracellular SNO (HSNO, L-cysNO, or L-cysNO-gly) releases NO to activate sGC and cause vasodilation.

Supplementary Figure S2. Tests for the role of the NO/cGMP pathway, the endothelium, and extracellularly released NO in L-cysNO- and D-cysNO-mediated vasodilation in isolated sheep femoral arteries (n=5). Arterial strips were denuded of endothelium (except in C and D), and were constricted with phenylephrine followed by cumulative exposure to L-cysNO (A, C, E) or D-cysNO (B, D, F) in the absence and presence of ODQ (A, B), endothelium (C, D), or CPTIO (E, F). A, B) ODQ right-shifts the dose response curves of both L- and D-cysNO. C, D) Endothelium-denudation does not affect L- or D-cysNO mediated vasorelaxation. E, F) CPTIO decreases the Emax of the dose response curves of both L- and D-cysNO. * p<0.05, paired t tests.

Supplementary Figure S3. Role of thiols located on the extracellular plasma membrane in L-cysNO- and D-cysNO-mediated vasodilation (n≥5 except C). Isolated sheep femoral arterial strips were incubated with the membrane-impermeable thiol modifier HMBA for 30 min to block the thiols on the surface of the plasma membrane. Following incubation, the arterial strips were extensively washed and then constricted with phenylephrine. Relaxation responses of arterial strips with and without HMBA pretreatment to L- (A) or D-cysNO (B) are compared, and show no effect of HMBA treatment. C) Blocking effects of HMBA on membrane surface thiols in isolated arterial segments as a function of time post-treatment (n=4). Sheep femoral arterial segments were incubated with HMBA (10μM) for 30 min and the quantity of the membrane surface thiols was measured by Ellman’s test[77] at specified time points before (control) and after (posTx) the incubation. Concentration was calculated by dividing the quantity by wet tissue weight. * for p<0.05 vs control. Extracellular thiols were decreased by more than 30% for at least 1h following HMBA treatment. Membrane surface thiol concentrations were significantly elevated 200 min after treatment, for reasons yet unknown. D) HMBA markedly accelerates the degradation of L-cysNO in PBS suggesting that HMBA is a SNO-depleting agent, which is why we chose to wash it out of the vessel bath prior to addition of the SNOs.

Supplementary Figure S4. Role of cellular uptake via the L-type amino acid transporter LAT in L- and D-cysNO-mediated vasodilation in isolated femoral arteries (n≥5). A,B) effects of LAT inhibitors BCH and Thr on the EC50 of L- and D-cysNO. EC50 of GSNO dose response curve in isolated femoral arteries is also shown for comparison. C, D, E, F) dose response curves of L- and D-cysNO in the absence and presence of BCH and Thr. LAT inhibitors BCH and Thr not only fail to cause a right-shift, as would be expected if the LAT played a role, but even left-shift the dose response curves of L- and D-cysNO indicating that uptake of SNO as an intact entity is not a prerequisite for its vasodilation, but may actually suppress vasodilatory responses to extracellular SNOs. *p<0.05, One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni test.

Supplementary Figure S5. Tests of the effectiveness of the membrane-impermable NO scavenger CPTIO (n=4). CPTIO abolishes free NO-mediated vasodilation, indicating that CPTIO offers an effective test of whether SNO-mediated vasodilation occurs by release of NO from the SNO outside the cell.

Supplementary Figure S6. Tests for the role of vascular NOSs in GSNO-mediated vasodilation in isolated sheep mesenteric arteries (n=5). The non-selective NOSs inhibitor L-NAME does not alter GSNO-mediated vasodilation.

Supplementary Figure S7. Effects of repeated GSNO pretreatment on contractile tension achieved prior to GSNO dose response experiments, demonstrating that GSNO pretreatment did not affect (p=0.85) the absolute contractile tension of the vessels before GSNO dose responses were determined. Average plateau tension of over 18 segments from 6 sheep is shown.

Supplementary Figure S8. The effects of GSH and blank control of GSNO (BGSNO) pretreatment on GSNO-mediated vasodilation (n=5). BGSNO is the blank control of GSNO, and was made from acidified glutathione and nitrate (instead of nitrite), which do not react with one another to produce GSNO. Experiments were performed in the same manner as in Fig 2A.

Supplementary Figure S9. In vitro test for the possibility that nitrite stimulates the release of NO from GSNO. Tests were performed in the absence (A) and presence (B) of arteries. Nitrite concentrations as high as 50 μM do not increase the rate of release of NO from GSNO in PBS (pH 7.4) in a purge vessel in line with a chemiluminescence NO analyzer. A representative trace of three similar experiments is shown.

Supplementary Figure S10. Effects of nitrite on NO and NO-independent vasodilation in isolated sheep arteries (n=5). A) In contrast to the potentiating effect of nitrite on GSNO-mediated vasodilation (Figure 2E) nitrite does not alter NO-mediated vasodilation. B) Nitrite does not alter vasodilation by the non-sGC-dependent pathway of ROCK2 inhibition by fasudil.

Supplementary Figure S11. Measurements seeking to detect free NO released from isolated arteries following stimulation by GSNO. A) Experimental protocol. Isolated sheep femoral arteries were exposed to GSNO for 45 min to achieve tachyphylaxis, and then exposed to HEPES buffer (group a) or nitrite (group b) to abrogate the tachyphylaxis. B, C ) Representative traces of NO signals measured by chemiluminescence in a purge vessel filled with PBS (pH=7.4). B) 50 μM GSNO was injected into 20 ml PBS containing 0.5 ml of tissue homogenate (4 μg/ml protein) from group a or b. The NO signals are not significantly different between vessel groups, suggesting that if GSNO stimulates the release of free NO,from a preformed store it is below the limit of detection by this method (~5 to 25 nM). C) NO sensitivity of the method in the absence and presence of tissue homogenates. Different concentrations of NO were injected into 20ml PBS in the absence and presence of 0.5ml of homogenate from arteries without treatment. The NO sensitivity was not altered by the tissue homogenates, indicating that homogenates do not significantly scavenge NO in the purge vessel, and in both cases the limit of sensitivity was between 5 and 25 nM NO. A representative trace of three similar experiments is shown. Similar results were obtained in experiments performed with isolated artery instead of its homogenate.