Abstract

Triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) is the most aggressive form of breast cancer with limited options of targeted therapy. Recent findings suggest that the clinical course of TNBC may be modified by the presence of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) and chemokine’s expression, such as CCL5. Diverse studies have shown that CCL5 suppresses anti-tumor immunity and it has been related to poor outcome in different types of cancer while in other studies, this gene has been related with a better outcome. We sought to determine the association of CCL5 with the recruitment of TILs and other immune cells. With this aim we evaluated a retrospective cohort of 72 TNBC patients as well as publicly available datasets. TILs were correlated with residual tumor size after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) and CCL5 expression. In univariate analysis, TILs and CCL5 were both associated to the distant recurrence free survival; however, in a multivariate analysis, TILs was the only significant marker (HR = 0.336; 95%IC: 0.150–0.753; P = 0.008). CIBERSORT analysis suggested that a high CCL5 expression was associated with recruitment of CD8 T cells, CD4 activated T cells, NK activated cells and macrophages M1. The CD8A gene (encoding for CD8) was associated with an improved outcome in several public breast cancer datasets.

Introduction

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is a heterogeneous group of breast tumors characterized by the lack of expression of estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor and HER2. TNBC is the most aggressive subtype of breast tumors because its biology and the limited options of targeted therapy1,2. Several efforts are being conducted to characterize its complexity and heterogeneity by combining structural and functional genomics approaches3–6.

Nowadays, there are several reports demonstrating the crucial role of immunity in TNBC biology, suggesting the potential involvement of immunotherapy to treat this malignancy where tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) are associated with better outcomes and response to chemotherapy7–12. TILs are constituting an important factor to predict in the outcome of TNBC in the neoadjuvant (pretreated or treated tumors) or in the adjuvant setting10,13–15. Evaluate TILs is a raw measurement of an immunological process where information of cellular subsets or cellular states is missing. Higher expression of cytotoxic molecules, T cell-related genes, Th1-related cytokines, and B cell markers were previously correlated with pathological complete response in breast cancer treated with anthracycline-based NAC8,11,13.

Despite the number of covariates that could influence biologically the activity of infiltrating lymphocytes, TILs evaluation per se has shown to predict the clinical outcome independently of other prognostic factors. Interestingly, a recent work has shown that some gene regulatory networks are shared among different immune cell subtypes while local sub networks define the phenotype; however, tumor-induced changes in local sub networks confers plasticity to immune cells producing a tumor-friendly environment, suggesting a need to improve the molecular characterizations of infiltrating immune cells16.

In a previous work to identify genes of prognostic value in TNBC, we identified CCL5, DDIT4 y POLR1C as independent prognostic factors where a high CCL5 expression was associated with a better prognosis (HR = 0.6, CI95%: 0.53–0.86)17. This good prognostic value was contrasting with many reports evaluating other cancer types. The scientific literature describe a dual role for CCL5 in cancer, attributing it a good outcome or a poor outcome role18,19.

The CCL5 (C-C motif chemokine ligand 5) gene belongs to the chemokine superfamily and encodes a protein that induces lymphocytes and monocytes migration. This gene has a higher expression in HER2-enriched and basal breast cancer subtypes than luminal tumors20,21. There are reports indicating that CCL5 attracts immunosuppressive cells promoting the immune tolerance or conversely, it is involved in the recruitment of immune effectors cells22.

We evaluated the association of CCL5 expression with clinicopathological features and the recruitment of TILs and subsets of immune cells in TNBC, and its influence in patients’ outcome.

Results

Clinicopathological features according to CCL5 expression and TILs

In 72 TNBC evaluated patients, the median age was 47.5 years (range: 24 to 78). There were not statistical differences in the clinopathological features, except in the residual tumor size with larger tumors in low TILs group (P = 0.017) and CCL5 (P = 0.053) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinicopathological characteristics of evaluated patients according to CCL5 expression and TILs count.

| Clinicopathological characteristics | CCL5 | P-value | TIL’s count | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <median n(%) | ≥median n(%) | Low TILs | High TILs | |||

| n (%) | n (%) | |||||

| TOTAL | 36 (50.0) | 36 (50.0) | 43 (59.7) | 29 (40.3) | ||

| Age | 0.281 | 0.322 | ||||

| Median (range) | 44.5 (24–78) | 48.5 (29–72) | 46.9 (24–72) | 49.8 (29–78) | ||

| Menopausal Status | 0.238 | 0.812 | ||||

| Pre | 20 (58.8) | 14 (41.2) | 21 (61.8) | 13 (38.2) | ||

| Post | 16 (42.1) | 22 (57.9) | 22 (57.9) | 16 (42.1) | ||

| Clinical stage | 0.674 | 0.679 | ||||

| IIA-IIB | 2 (33.3) | 4 (66.7) | 3 (50.0) | 3 (50.0) | ||

| IIIA-IIIC | 34 (51.5) | 32 (48.5) | 40 (60.6) | 26 (39.4) | ||

| Chemotherapy | NA | NA | ||||

| A | 11 (34.4) | 21 (65.6) | 17 (53.1) | 15 (46.9) | ||

| A + T | 25 (67.6) | 12 (32.4) | 25 (67.6) | 12 (32.4) | ||

| Others | 0 (0) | 3 (100) | 1 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) | ||

| Node Involvement | 0.322 | 0.211 | ||||

| Negative | 10 (41.7) | 14 (58.3) | 12 (50.0) | 12 (50.0) | ||

| Positive | 26 (55.3) | 21 (44.7) | 31 (66.0) | 16 (34.0) | ||

| Positive Nodes | 0.312 | 0.409 | ||||

| 0 | 10 (41.7) | 14 (58.3) | 12(50.0) | 12 (50.0) | ||

| 1–3 | 12 (48.0) | 13 (52.0) | 17 (68.0) | 8 (32.0) | ||

| >3 | 14 (63.6) | 8 (36.4) | 14 (63.6) | 8 (36.4) | ||

| Residual tumor size (mm) | 0.053 | 0.017 | ||||

| Median (range) | 50 (0–250) | 34.5 (0–125) | 50 (0–250) | 34.5 (0–80) | ||

*NA: not applicable.

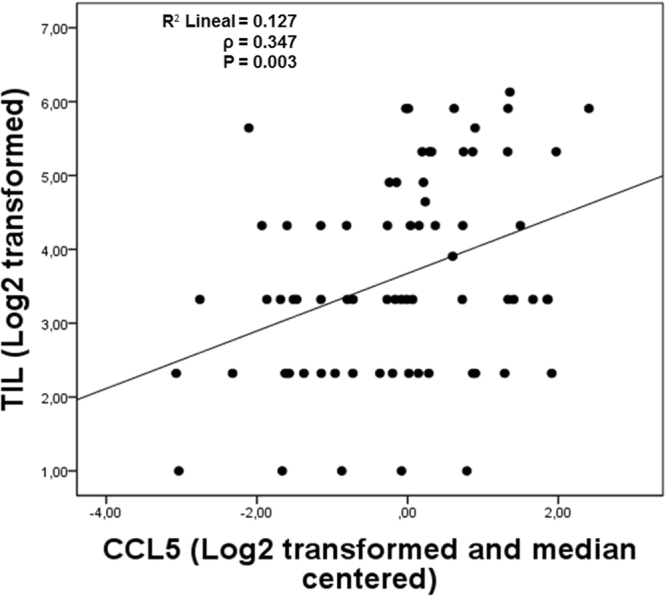

There is a direct correlation between CCL5 and TILs

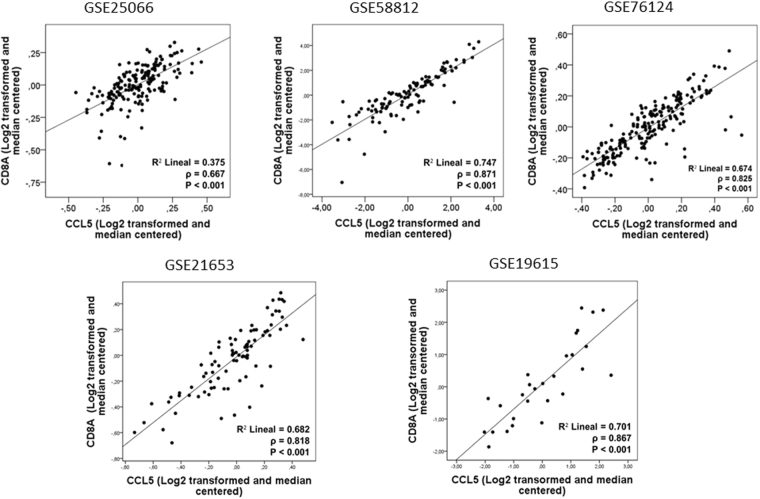

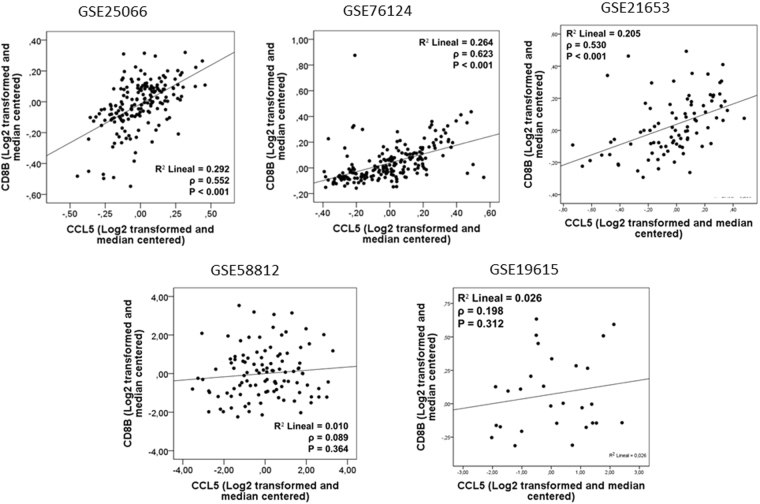

A significant correlation between TILs and CCL5 (ρ = 0.347, P = 0.003) was observed in our retrospective TNBC cohort (Fig. 1). In addition, in independent public datasets, a positive correlation between CCL5 and CD8A was observed (GSE25066: ρ = 0.667, P < 0.001; GSE58812: ρ = 0.871, P < 0.001; GSE76124: ρ = 0.825, P < 0.001; GSE21653: ρ = 0.818, P < 0.001; GSE19615: ρ = 0.867, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2), as well as a correlation between CCL5 and CD8B (GSE25066: ρ = 0.552, P < 0.001; GSE76124: ρ = 0.623, P < 0.001; GSE21653: ρ = 0.530, P < 0.001) (Fig. 3).

Figure 1.

A positive correlation between CCL5 and TILs count was observed in the Peruvian cohort (P = 0.003).

Figure 2.

Expression of CCL5 was directly correlated with the expression of CD8A in all datasets.

Figure 3.

CD8B expression was associated with CCL5 in 3 out 5 datasets of TNBC.

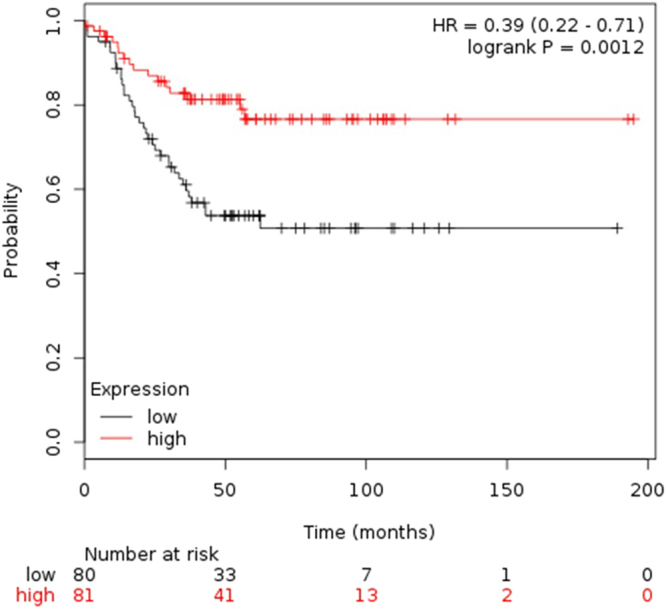

TILs and CCL5 are related with the outcome

In the univariate analysis of the retrospective cohort for distant metastases-free survival, TILs count (HR = 0.276; 95%IC: 0.128–0.593; P = 0.001) and CCL5 (HR = 0.401; 95%IC: 0.206–0.781; P = 0.007) were both associated with distant recurrence free survival (DRFS). In the multivariate analysis between CCL5 and TILs, TILs remains as an independent prognostic factor (HR = 0.336 per unit of change; 95%CI: 0.150–0.753; P = 0.008) while CCL5 expression had not significant prognostic value (HR = 0.573 per unit of change; 95%CI: 0.285–1.154; P = 0.119) (Table 2). Due to tumor heterogeneity could add bias in the evaluation of biomarkers we performed 1000 resampling with the bootstrap method to verify the robustness of the model23. After this analysis, results obtained were a HR = 0.37 (95%CI: 0.135–0.827) and HR = 0.56 (95%IC: 0.239–1.240) for TILS and CCL5, respectively.

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of TILs count and CCL5 expression as categorical variables.

| HR | CI95% | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | |||

| TILs | |||

| Low | 1 | ||

| High | 0.276 | 0.128–0.593 | 0.001 |

| CCL5 | |||

| <median | 1 | ||

| ≥median | 0.401 | 0.206–0.781 | 0.007 |

| Multivariate analysis | |||

| TILs | |||

| Low | 1 | ||

| High | 0.336 | 0.150–0.753 | 0.008 |

| CCL5 | |||

| <median | 1 | ||

| ≥median | 0.573 | 0.285–1.154 | 0.119 |

An analysis of CCL5 expression in KM plotter (http://kmplot.com/)24 shown that a high CCL5 expression was associated with a better outcome in TNBC patients, either in the meta-analysis of all datasets (HR = 0.39, CI95%: 0.22–0.71; P = 0.0012) (Fig. 4) or analyzing each dataset separately (n = 3) (Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 4.

Meta-analysis of CCL5 in recurrence-free survival (RFS) in TNBC (using the median of expression as cutoff) in databases of KM plotter. A High expression of CCL5 was associated with good prognosis (P = 0.0012).

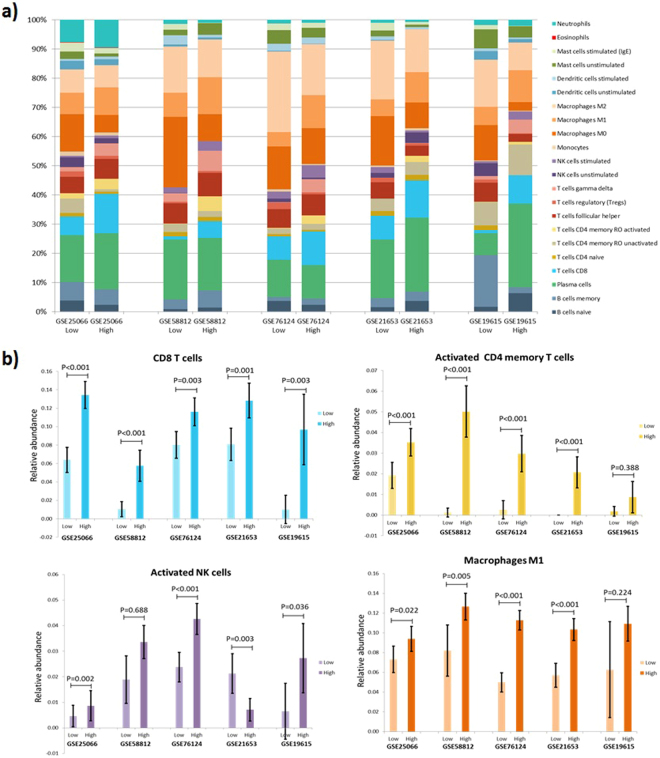

Immune cell composition according to CCL5 expression

CIBERSORT analysis (https://cibersort.stanford.edu/)25 in five public TNBC datasets suggested that a high CCL5 expression (comparing the upper tertile vs the lower tertile) is associated with recruitment of CD8 cells, activated CD4 memory T cells, activated NK cells and Macrophages M1 (Fig. 5). Regarding regulatory T cells (Treg) cells, an increase was observed in patients with low expression of CCL5, but this was statistically significant in only two datasets (GSE25066: 2% vs. 1%, P = 0.029; GSE76124: 2% vs. 1%, P < 0.001). Similar results were found when datasets were split into two (median as cutoff) or four groups (upper quartile vs. lower quartile) (Supplementary data S1). All relative fractions and P-values obtained from the CIBERSORT analysis are showed in Supplementary data S2.

Figure 5.

Relative fractions of 22 leukocyte subtypes (LM22 signature) evaluated by CIBERSORT in five TNBC datasets according to CCL5 expression (1st tertile vs 3rd tertile) (a). Differences between immune cell subtypes according to CCL5 expression. Analysis was limited to cases with CIBERSORT p-value < 0.05 (b).

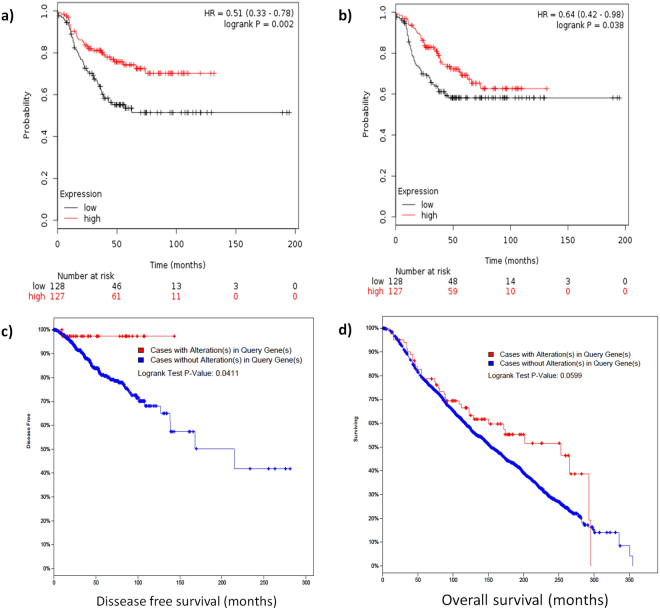

CD8A expression is related with the outcome

Because the main lineage biomarkers in CD8 T cells are CD8A and CD8B expression, these genes were used as indicators of CD8 cells infiltration. A high expression of either CD8A or CD8B was related with an improved outcome in KM-Plotter analysis (Figs 6A,B). Over expression of CD8A was related with a better survival in the TCGA and METABRIC datasets (Figs 6C and 3D).

Figure 6.

Meta-analysis in KM-Plotter showed that an high expression of CD8A (a) and CD8B (b) are related with a better relapse free survival in TNBC. CD8A overexpression is related with better disease free survival in the TCGA (c) and better overall survival in the METABRIC (d) datasets (all breast cancer subtypes).

Discussion

In this study we combine analysis of patients’ samples and evaluation in bioinformatics platforms to assess the effect of CCL5 in the infiltration of immune cells. Although we inferred the immune cell composition form genomic data, we used a robust and validated algorithm26.

Several studies have pointed the value of TILs in the outcome in breast cancer and other solid tumors. A previous study showed that a 20% cutoff in stromal TILs is able to discriminate low vs high infiltration and detect significant differences in the outcome in TNBC patients27. In a meta-analysis of 8 studies, Ibrahim et al. (2014), showed that triple negative breast tumors rich in TILs had an 30% reduction in risk of recurrence, 22% reduction in risk of distant recurrence and 34% in reduction in the risk of death28.

In our analysis, there was direct correlation between TILs and CCL5 expression in TNBC; therefore other reports describe that not only pro-immune markers (CCL5 [ρ = 0.677, P < 0.001], CD45RO, CD80, CXCL9, and CXCL13), but also immunosuppressive markers such as LAG3, IDO1, CTLA-4, TIGIT, BTLA, and FOXP3 had a positive correlation with increased TILs15,29.

In regard to CCL5, several reports describe that a high expression of this gene is associated to a poor outcome30,31. There are several mechanisms possibly linking CCL5 with aggressiveness and oncogenic features. Mesenchymal stem cells are induced by tumor cells to secret CCL5 to enhance motility and metastasis32. Interestingly, in a model of gastric cancer, tumor cells induced CD4+ T-cells to secrete CCL5, which in turn, induced apoptosis in CD8+ T cells, while neutralization of CCL5 with monoclonal antibodies induced tumor suppression33. After radiotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer, CCL5 is overexpressed and can induce macrophage infiltration, promoting tumor progression34. Regarding breast cancer, it has been described that CCL5-deficient mice are resistant to mammary tumor growth19. In stage II breast cancer, high expression of CCL5 (assessed by immunohistochemistry) has been associated with disease progression35.

On the other hand, in melanoma, intratumoral injection of IFN-β induces expression of CCL5 and CXCR3 ligands and administration of IFN-β with anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibodies suppressed the tumor growth and prolonged the survival in a murine model36.

In ER- breast cancer, tumor-infiltrating FOXP3+ lymphocytes and CCL5 expression were associated to a good outcome37–39. deLeeuw et al. (2012) showed that the role in the outcome of FOXP3+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes depends of the tumor site and microenvironment features40. In that way, these conditions could be the responsible of the different prognostic value seen in CCL5.

In our study, CCL5 lacks of prognostic ability when is adjusted to TILs (Table 2) suggesting that in TNBC, levels of TILs infiltration is the most important immunological variable. In a similar way, Denkert et al. (2015) reported that CCL5 is also related to an increased pCR in TNBC patients (OR, 1.30 per ≥ Δ Ct; 95%CI, 1.07 to 1.56; P = 0.007), but after adjusting to TILs count it was no significant41.

We identified several patterns of infiltrations associated to high CCL5 expression characterized by a higher infiltration of CD8 T-cells, CD4 memory activated T-cells, NK activated T-cells and Macrophages M1 (analyzed in CIBERSORT). Because the higher infiltration of CD8 T-cells we next evaluated the association of CD8A with the outcome in KM-plotter (for TNBC) and in two genomic projects, TCGA and METABRIC (for all subtypes), where this gene was associated to a better outcome (Fig. 3). The mechanistic antitumor role of CD8 T-cells, CD4 memory activated T cells should be studied in detail.

Traits of infiltrating immune sets were previously correlated with the clinical outcome. Interestingly, the prognostic value of immune cells is maintained among different cancer types26. In the particular case of breast cancer, a prior study described that tumor infiltration with B cells memory, monocytes and dendritic cell resting were associated to resistance to NAC and macrophages M1 and B cells naïve were related to the pathological complete response in ER positive tumors while in ER negative tumors, macrophages M2 and mast cell resting were related to resistance to NAC and T-cells follicular helper were associated with higher probability of pathological complete response42.

In conclusion, although CCL5 expression is associated to a better outcome in breast cancer, particularly in TNBC, TILs assessment remains the stronger and more significant prognostic immunological marker although characterization of cellular states of TILs should provide a more precise prognostic biomarker.

Material and Methods

Patients

We evaluated a retrospective cohort of Peruvian patients who had residual tumors after NAC whose tumors were evaluable for TILs and CCL5. In total, 72 patients were included in the analysis (one patient was excluded because its TILs count was zero). The clinicopathological parameters evaluated were: age at diagnosis, menopausal status, clinical stage, node involvement, residual tumor size, TILs count, distant recurrence status and time to distant recurrence.

Breast Cancer Datasets

Five independent datasets were obtained from GEO (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), to evaluate the immune cells composition according to the expression of CCL5.

GSE25066

We selected 178 TNBC cases (determined by immunohistochemistry). Samples were collected before NAC. Gene expression profiling was measured with U133A Affymetrix microarray platform (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

GSE58812

We evaluated all the 107 TNBC of this dataset. Gene expression was profiled with Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

GSE76124

This dataset was composed of 198 TNBC cases. Gene expression was profiled with Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

GSE21653

We included 87 TNBC cases. Gene expression was profiled with Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

GSE19615

We evaluated 28 TNBC cases. Gene expression was profiled with Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

TILs assessment

Post-NAC tumors were submitted for pathologic evaluation. After they were stained with H&E staining, determination of percentage of stromal lymphocytic infiltration (%TIL) was done according to method described by Dieci et al.43 A cutoff value of 20% was selected to discriminate high vs low TILs27.

Gene expression analysis

Tumor-rich regions of formalin-fixed paraffin embedded tumor blocks were serially cuttted in 3–6 μm sections. RNA was extracted and purified using the RNeasy FFPE Kits (Qiagen). Gene expression analysis was performed by NanoString (Seattle, WA). Samples were assayed on a Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Santa Clara,CA) to determine the concentration of RNA. Raw data was subtracted from background with spike-controls and then was normalized by dividing the geometric mean of seven housekeeper-control genes: ACTB, B2M, G6PD, GAPDH, GUSB, POLR1B, RPLPO and TUBB.

Evaluation of CCL5 and TILs correlation

Housekeeper-normalized gene expression values of CCL5, CD8A and CD8B were log2 transformed and median centered, while TILs count was log2 transformed. Spearman’s rank correlation analysis was used to assess the relationship between these markers.

Survival Analysis

In the Peruvian cohort, cox Proportional-Hazards Regression was used to evaluate the impact of TILs and CCL5 in the outcome. Both were evaluated as categorical variables (TILs < 20% and TILs ≥ 20%; CCL5 < median and CCL5 ≥ median). To validate the result of the cox model, the HR and 95% confidence intervals were estimated with 1,000 bootstrap resampling. The analysis was done using the package boot in R language.

Additionally, the effect of CCL5 on recurrence free survival was assessed using the online tool KM plotter (http://kmplot.com/analysis/)24 in all TNBC patients (median as cutoff).

Analysis of immune cells composition from gene expression data

The datasets were independently analyzed. The probe’s IDs were changed to its respective genes symbols and then genes expressions levels were collapsed to the maximum value. Each data set was split according to CCL5 expression using tertiles where samples with central values (group 2) were excluded.

We used the online analytical platform CIBERSORT (https://cibersort.stanford.edu/)25 in order to estimate the relative proportions of 22 immune cell types. Analyses were done with 100 permutations, enabled quantile normalization and default statistical parameters. The results were filtered by a maximum p-value of 0.05. Comparisons of relative fractions were done with the Mann–Whitney U test.

Evaluation of CD8 effect on the outcome

We assessed the impact of CD8A and CD8B expression on the outcome. For this analysis we used two online platforms; KM plotter (http://kmplot.com/analysis/)24 (TNBC cases) and cBioPortal (http://www.cbioportal.org/)44,45 (TCGA provisional and METABRIC datasets).

Ethical considerations

This study involves a reanalysis of gene expression and clinical data obtained in previous studies.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by a research grant of AUNA.

Author Contributions

Study design: J.M.A., H.L.G. and J.A.P. Nanostring gene expression analysis: J.M.B. TILs count: R.S. In silico data collection and data preprocessing: J.M.A., A.C.G., L.B., and Z.D.M. Tumor samples collection: J.A.P., F.D. and H.L.G. Patient data collection: F.D. and H.L.G. Statistical Analysis: J.M.A., C.F. and L.B. Data interpretation: J.M.A., C.F., J.M.B., R.S. and J.A.P., Writing of Manuscript: All authors. Preparation of tables and figures: J.M.A. A.C.G. and Z.M. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-23099-7.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Fisher B, et al. Effect of preoperative chemotherapy on the outcome of women with operable breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 1998;16:2672–2685. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.8.2672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith IC, et al. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Breast Cancer: Significantly Enhanced Response With Docetaxel. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002;20:1456–1466. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.6.1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lehmann BD, et al. Identification of human triple-negative breast cancer subtypes and preclinical models for selection of targeted therapies. J. Clin. Invest. 2011;121:2750–2767. doi: 10.1172/JCI45014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balko JM, et al. Profiling of residual breast cancers after neoadjuvant chemotherapy identifies DUSP4 deficiency as a mechanism of drug resistance. Nat. Med. 2012;18:1052–1059. doi: 10.1038/nm.2795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balko JM, et al. Molecular Profiling of the Residual Disease of Triple-Negative Breast Cancers after Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Identifies Actionable Therapeutic Targets. Cancer Discov. 2014;4:232–245. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawazu M, et al. Integrative analysis of genomic alterations in triple-negative breast cancer in association with homologous recombination deficiency. PLOS Genet. 2017;13:e1006853. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stagg J, Allard B. Immunotherapeutic approaches in triple-negative breast cancer: latest research and clinical prospects. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2013;5:169–81. doi: 10.1177/1758834012475152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loi S, et al. RAS/MAPK Activation Is Associated with Reduced Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Therapeutic Cooperation Between MEK and PD-1/PD-L1 Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016;22:1499–1509. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loi S, et al. Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes are prognostic in triple negative breast cancer and predictive for trastuzumab benefit in early breast cancer: results from the FinHER trial. Ann. Oncol. 2014;25:1544–1550. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adams S, et al. Prognostic value of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in triple-negative breast cancers from two phase III randomized adjuvant breast cancer trials: ECOG 2197 and ECOG 1199. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014;32:2959–66. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.55.0491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.West NR, et al. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes predict response to anthracycline-based chemotherapy in estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13:R126. doi: 10.1186/bcr3072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamaguchi R, et al. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are important pathologic predictors for neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with breast cancer. Hum. Pathol. 2012;43:1688–1694. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2011.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Denkert C, et al. Tumor-Associated Lymphocytes As an Independent Predictor of Response to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Breast Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010;28:105–113. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.7370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Issa-Nummer Y, et al. Prospective validation of immunological infiltrate for prediction of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-negative breast cancer–a substudy of the neoadjuvant GeparQuinto trial. PLoS One. 2013;8:e79775. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dieci MV, et al. Prognostic value of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes on residual disease after primary chemotherapy for triple-negative breast cancer: a retrospective multicenter study. Ann. Oncol. 2014;25:611–618. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han P, Gopalakrishnan C, Yu H, Wang E. Genes (Basel). 2017. Gene Regulatory Network Rewiring in the Immune Cells Associated with Cancer; p. 308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pinto, J. A. et al. A prognostic signature based on three-genes expression in triple-negative breast tumours with residual disease. npj Genomic Med. 1 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Zhang Y, et al. Role of CCL5 in invasion, proliferation and proportion of CD44+/CD24− phenotype of MCF-7 cells and correlation of CCL5 and CCR5 expression with breast cancer progression. Oncol. Rep. 2009;21:1113–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Y, et al. A novel role of hematopoietic CCL5 in promoting triple-negative mammary tumor progression by regulating generation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cell Res. 2013;23:394–408. doi: 10.1038/cr.2012.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Velasco-Velázquez M, et al. CCR5 antagonist blocks metastasis of basal breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2012;72:3839–50. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fertig EJ, Lee E, Pandey NB, Popel AS. Analysis of gene expression of secreted factors associated with breast cancer metastases in breast cancer subtypes. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:12133. doi: 10.1038/srep12133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu J, et al. Local production of the chemokines CCL5 and CXCL10 attracts CD8 + T lymphocytes into esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2015;6:24978–24989. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li J, et al. Identification of high-quality cancer prognostic markers and metastasis network modules. Nat. Commun. 2010;1:34. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Györffy B, et al. An online survival analysis tool to rapidly assess the effect of 22,277 genes on breast cancer prognosis using microarray data of 1,809 patients. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2010;123:725–731. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0674-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Newman AM, et al. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat. Methods. 2015;12:453–457. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gentles AJ, et al. The prognostic landscape of genes and infiltrating immune cells across human cancers. Nat. Med. 2015;21:938–945. doi: 10.1038/nm.3909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loi, S. et al. Abstract S1-03: Pooled individual patient data analysis of stromal tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in primary triple negative breast cancer treated with anthracycline-based chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 76 (2016).

- 28.Ibrahim EM, Al-Foheidi ME, Al-Mansour MM, Kazkaz GA. The prognostic value of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in triple-negative breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2014;148:467–476. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-3185-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee HJ, et al. Prognostic and predictive value of NanoString-based immune-related gene signatures in a neoadjuvant setting of triple-negative breast cancer: relationship to tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2015;151:619–627. doi: 10.1007/s10549-015-3438-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.D’Esposito V, et al. Adipose microenvironment promotes triple negative breast cancer cell invasiveness and dissemination by producing CCL5. Oncotarget. 2016;7:24495–24509. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Velasco-Velázquez M, Pestell RG. The CCL5/CCR5 axis promotes metastasis in basal breast cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2013;2:e23660. doi: 10.4161/onci.23660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karnoub AE, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells within tumour stroma promote breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2007;449:557–563. doi: 10.1038/nature06188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sugasawa H, et al. Gastric cancer cells exploit CD4+ cell-derived CCL5 for their growth and prevention of CD8+ cell-involved tumor elimination. Int. J. Cancer. 2008;122:2535–2541. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang X, et al. IL-6 Mediates Macrophage Infiltration after Irradiation via Up-regulation of CCL2/CCL5 in Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Radiat. Res. 2017;187:50–59. doi: 10.1667/RR14503.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yaal-Hahoshen N, et al. The Chemokine CCL5 as a Potential Prognostic Factor Predicting Disease Progression in Stage II Breast Cancer Patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006;12:4474–4480. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Uehara J, et al. Intratumoral injection of IFN-β induces chemokine production in melanoma and augments the therapeutic efficacy of anti-PD-L1 mAb. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017;490:521–527. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.06.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chew V, et al. Chemokine-driven lymphocyte infiltration: an early intratumoural event determining long-term survival in resectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut. 2012;61:427–438. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.West NR, et al. Tumour-infiltrating FOXP3+ lymphocytes are associated with cytotoxic immune responses and good clinical outcome in oestrogen receptor-negative breast cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 2013;108:155–162. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang X, et al. Cancer-FOXP3 directly activated CCL5 to recruit FOXP3+ Treg cells in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Oncogene. 2017;36:3048–3058. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.deLeeuw RJ, Kost SE, Kakal JA, Nelson BH. The Prognostic Value of FoxP3+ Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes in Cancer: A Critical Review of the Literature. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012;18:3022–3029. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Denkert C, et al. Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes and Response to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy With or Without Carboplatin in Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2–Positive and Triple-Negative Primary Breast Cancers. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015;33:983–991. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ali HR, Chlon L, Pharoah PDP, Markowetz F, Caldas C. Patterns of Immune Infiltration in Breast Cancer and Their Clinical Implications: A Gene-Expression-Based Retrospective Study. PLoS Med. 2016;13:e1002194. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dieci MV, et al. Update on tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in breast cancer, including recommendations to assess TILs in residual disease after neoadjuvant therapy and in carcinoma in situ: A report of the International Immuno-Oncology Biomarker Working Group on Breast Cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2017.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gao J, et al. Integrative Analysis of Complex Cancer Genomics and Clinical Profiles Using the cBioPortal. Sci. Signal. 2013;6:pl1–pl1. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cerami, E. et al. The cBio Cancer Genomics Portal: An Open Platform for Exploring Multidimensional Cancer Genomics Data. Cancer Discov. 2 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.