Abstract

Mesophotic coral ecosystems, which occur at depths of ~40 to 150 m, have received recent scientific attention as potential refugia for organisms inhabiting deteriorating shallow reefs. These ecosystems merit research in their own right, as they harbor both depth-generalist species and a distinctive reef-fish fauna. Reef ecosystems just below the mesophotic are globally underexplored, and the scant recent literature that mentions them often suggests that mesophotic ecosystems transition directly into those of the deep sea. Through submersible-based surveys in the Caribbean Sea, we amassed the most extensive database to date on reef-fish diversity between ~40 and 309 m at any single tropical location. Our data reveal a unique reef-fish assemblage living between ~130 and 309 m that, while taxonomically distinct from shallower faunas, shares strong evolutionary affinities with them. Lacking an existing name for this reef-faunal zone immediately below the mesophotic but above the deep aphotic, we propose “rariphotic.” Together with the “altiphotic,” proposed here for the shallowest reef-faunal zone, and the mesophotic, the rariphotic is part of a depth continuum of discrete faunal zones of tropical reef fishes, and perhaps of reef ecosystems in general, all of which warrant further study in light of global declines of shallow reefs.

Introduction

Studies of deep tropical-reef ecosystems have surged during the past decade1–10. This is due in part to the global decline of shallow coral reefs having sparked interest in the potential for deep reefs to act as refugia for shallow-water organisms stressed by warming surface waters or deteriorating reefs. Variously called the “coral-reef twilight zone” or “deep reefs,” mesophotic coral ecosystems are light-dependent coral communities at tropical and some higher latitudes that generally are considered to extend from 30–40 m to as deep as 150 m2,3,7,9,11. Although the boundary between shallow and mesophotic ecosystems initially was established based on the lower limit for conventional scuba diving rather than substantial turnovers in species composition2,4,11–13, there is supporting biological evidence for both corals14 and reef fishes15. The lower limit of the mesophotic is defined as the maximum depth at which there is sufficient penetration of sunlight to support photosynthesis and, hence, the growth of zooxanthellate coral reefs1,2. Some coral biologists divide the mesophotic into upper and lower portions, with a faunal transition of species around 60 m1,9,16.

Fish biologists have adopted the term “mesophotic” for tropical reef fishes (demersal and cryptic species that live on or visit coral or rocky bottoms) at similar depths just below shallow areas, at ~40 to 150 m depending on the method of study and maximum depth investigated3,7,10,13. A faunal break among reef fishes occurs between ~60 and 90 m, thus also resulting in the recognition of upper and lower mesophotic zones for such fishes3,7,8,10,17,18. The species composition of reef fishes inhabiting the upper mesophotic is similar to that on shallow coral reefs, whereas species inhabiting the lower mesophotic constitute an assemblage that is taxonomically distinct from shallow-reef taxa3,7,8,11,17. Abundance and biomass of fish species in the upper and lower mesophotic typically vary significantly3.

Maximum depths of investigation between 70 and 150 m in most studies of tropical mesophotic fish communities have precluded recognition of the lower boundary of the mesophotic zone, the nature of the reef-fish fauna below that zone, and the location of any deeper faunal breaks8,18–21. Two studies that recorded fishes to depths of 300 m only distinguished shallow (<30 m) from “deep-reef” (>50 m) faunas22,23, and several recent publications depict the mesophotic transitioning directly into aphotic deep-sea ecosystems11,24–26. Tropical ecosystems below 150 m thus have received little targeted scientific attention, a deficiency attributable to depth limits imposed by the rebreather/mixed-gas technology commonly used to explore mesophotic reefs, to the scarcity and high costs of deep-diving ROVs and submersibles, and to the inability of trawls to sample deep rocky habitat.

Our intensive efforts over the past six years using a manned submersible to study the diversity of mesophotic and deeper tropical fish communities at Curaçao Island in the Caribbean Sea have resulted in the most extensive database to date on the diversity and depth distributions of reef fishes between ~40 and 309 m at a single location anywhere in the tropics. This data set provided the opportunity to analyze variation in faunal assemblages (species composition and abundance) at mesophotic and greater depths, the results of which we report here.

Results and Discussion

Our data set comprises 4,436 depth observations of 71 reef-fish species observed and unambiguously identified between 40 and 309 m off Curaçao (Fig. 1, Tables 1–3). As described herein, results of our cluster analyses of these data reveal strong faunal breaks along the depth gradient that clearly point to the existence of a faunal zone immediately below the mesophotic that extends down to at least 309 m and that is home to a unique reef-fish fauna (Fig. 2). Many component species of this fauna have been described as new species as part of our investigation27–30 or remain undescribed. As there is no appropriate term in existing coral-reef literature for a demersal zone that is immediately below the mesophotic but above the deep aphotic regions, we propose “rariphotic” (rarus = scarce), to reflect the scarcity of light at sub-mesophotic depths. Below we discuss the boundaries and taxonomic composition of this fish-faunal zone off Curaçao. Providing a name for this faunal zone, as biologists have for the mesophotic, draws attention to its existence, emphasizes that the mesophotic is not the only “deep-reef” faunal zone below shallow coral reefs, and provides terminology with which to discuss it. As there is also no equivalent term in general use for shallow coral reefs above the mesophotic that follows the same naming scheme, we propose “altiphotic” (altus = high) to complete this classification of coral-reef faunal zones: altiphotic, mesophotic, rariphotic.

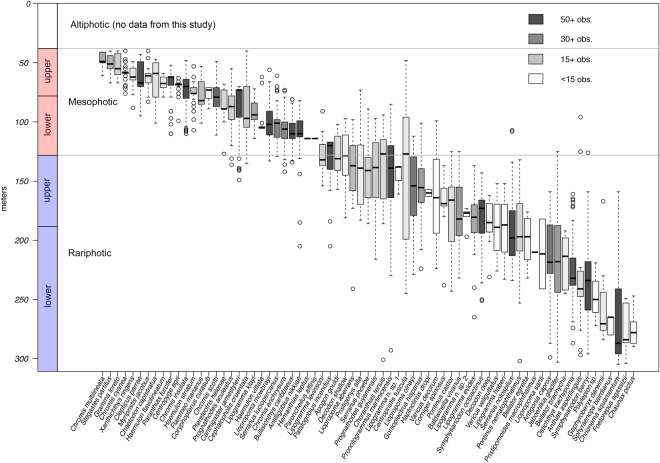

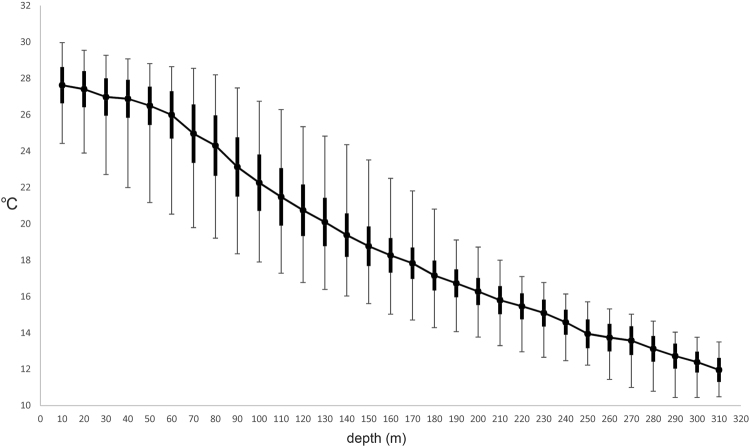

Figure 1.

Depth distributions of 71 mesophotic and rariphotic fishes derived from 4,436 depth observations between 40 and 309 m off Curaçao, southern Caribbean. Boxes indicate the 25th and 75th quantiles, whiskers are 1.5 the interquartile, and circles are outliers.

Table 1.

Fishes belonging primarily to the altiphotic (0–39 m) and mesophotic (40–129 m) zones based on visual observations and specimens collected between 40 and 309 m off Curaçao.

| Family | Genus | species | N | % in Mesophotic | % in Rariphotic | Faunal Zone Assignment off Curaçao | Depth Range off Curaçao (m) | Global Depth Range (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chaetodontidae | Chaetodon | capistratus | 17 | 100% | 0% | A/M | <40–101 | 0–101 |

| Gobiidae | Ptereleotris | helenae | 23 | 100% | 0% | A/M | <40––127 | 3–160 |

| Grammatidae | Gramma | loreto | 27 | 100% | 0% | A/M | <40–67 | 2–100 |

| Haemulidae | Haemulon | flavolineatum | 12 | 100% | 0% | A/M | <40–79 | 0–79 |

| Haemulon | vittatum | 17 | 100% | 0% | A/M | <40–105 | 0–105 | |

| Holocentridae | Myripristis | jacobus | 13 | 100% | 0% | A/M | <40–83 | 1–210 |

| Labridae | Clepticus | parrae | 287 | 100% | 0% | A/M | <40–95 | 0–145 |

| Pomacentridae | Chromis | cyanea | 42 | 100% | 0% | A/M | <40–76 | 3–76 |

| Chromis | multilineata | 49 | 100% | 0% | A/M | <40–61 | 1–91 | |

| Stegastes | partitus | 42 | 100% | 0% | A/M | <40–67 | 0–111 | |

| Serranidae | Paranthias | furcifer | 247 | 100% | 0% | A/M | <40–110 | 0–128 |

| Cephalopholis | cruentata | 32 | 97% | 3% | A/M | <40–135 | 1–170 | |

| Apogonidae | Paroncheilus | affinis | 5 | 100% | 0% | M | 114 | 15–300 |

| Balistidae | Xanthichthys | ringens | 15 | 100% | 0% | M | 49–88 | 0–190 |

| Chaetodontidae | Prognathodes | aculeatus | 29 | 93% | 7% | M | 55–136 | 1–177 |

| Gobiidae | Antilligobius | nikkiae | 255 | 97% | 3% | M | 82–205 | 73–205 |

| Coryphopterus | curasub | 5 | 100% | 0% | M | 70–97 | 70–97 | |

| Grammatidae | Lipogramma | klayi | 49 | 100% | 0% | M | 72–114 | 40–150 |

| Haemulidae | Haemulon | striatum | 33 | 100% | 0% | M | 53–107 | 1–210 |

| Holocentridae | Flammeo | marianus | 37 | 100% | 0% | M | 53–101 | 15–128 |

| Pomacanthidae | Centropyge | argi | 39 | 100% | 0% | M | 63–99 | 5–170 |

| Pomacentridae | Chromis | insolata | 213 | 100% | 0% | M | 40–110 | 20–152 |

| Chromis | scotti | 85 | 100% | 0% | M | 49–111 | 5–172 | |

| Chromis | cf. enchrysura | 68 | 94% | 6% | M | 73–142 | 70–172 | |

| Serranidae | Bullisichthys | caribbaeus | 262 | 87% | 13% | M | 81–134 | 81–548 |

| Hemanthias | leptus | 2 | 100% | 0% | M | 114 | 35–640 | |

| Liopropoma | mowbrayi | 111 | 98% | 2% | M | 56–133 | 24–133 | |

| Serranus | luciopercanus | 69 | 100% | 0% | M | 61–129 | 60–300 | |

| Tetraodontidae | Canthigaster | jamestyleri | 116 | 94% | 6% | M | 70–149 | 25–152 |

A species was assigned to the mesophotic zone (M) if >75% of occurrences are in that zone, to altiphotic/mesophotic zones (A/M) if it commonly occurs at depths <40 m32–34. N = number of depth observations from combined visual and collection data. Global depth ranges are from data generated in this study and elsewhere32–34.

Table 3.

Fishes belonging primarily to the rariphotic zone (130 to at least 309 m) zone based on visual observations and specimens collected between 40 and 309 m off Curaçao.

| Family | Genus | species | N | % in Mesophotic | % in Rariphotic | Faunal Zone Assignment off Curaçao | Depth Range off Curaçao (m) | Global Depth Range (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gobiidae | Varicus | veliguttatus | 5 | 0% | 100% | R | 152–289 | 152–293 |

| Grammatidae | Lipogramma | evides | 48 | 0% | 100% | R | 137–265 | 133–365 |

| Lipogramma | haberi | 3 | 0% | 100% | R | 153–233 | 153–233 | |

| Lipogramma | n. sp. 1 | 3 | 0% | 100% | R | 138–161 | 138–161 | |

| Lipogramma | n. sp. 2 | 5 | 0% | 100% | R | 173–197 | 173–197 | |

| Holocentridae | Corniger | spinosus | 10 | 0% | 100% | R | 137–238 | 45–275 |

| Labridae | Decodon | puellaris | 7 | 0% | 100% | R | 162–231 | 18–275 |

| Polylepion | n. sp. | 3 | 0% | 83% | R | 68–274 | 68–457 | |

| Labrisomidae | Haptoclinus | dropi | 2 | 0% | 100% | R | 157–167 | 157–275 |

| Percophidae | Chrionema | squamentum | 181 | 0% | 100% | R | 159–305 | 115–305 |

| Scorpaenidae | Pontinus | castor | 19 | 10% | 90% | R | 125–243 | 32–549 |

| Pontinus | nematophthalmus | 23 | 0% | 100% | R | 132–302 | 82–410 | |

| Serranidae | Anthias | asperilinguis | 19 | 16% | 84% | R | 96–297 | 69–393 |

| Baldwinella | cf. vivanus | 57 | 3% | 97% | R | 125–232 | 125–232 | |

| Gonioplectrus | hispanus | 56 | 9% | 91% | R | 101–224 | 35–460 | |

| Jeboehlkia | gladifer | 55 | 2% | 98% | R | 125–303 | 100–395 | |

| Liopropoma | olneyi | 76 | 25% | 75% | R | 112–229 | 112–229 | |

| Liopropoma | santi | 5 | 0% | 100% | R | 182–241 | 182–275 | |

| Serranus | notospilus | 101 | 2% | 98% | R | 107–234 | 7–234 | |

| Serranus | phoebe | 25 | 24% | 76% | R | 89–186 | 15–402 | |

| Symphysanodontidae | Symphysanodon | berryi | 117 | 1% | 99% | R | 126–296 | 100–500 |

| Symphysanodon | octoactinus | 153 | 0% | 100% | R | 143–251 | 130–640 | |

| Triglidae | Bellator | egretta | 7 | 0% | 100% | R | 176–232 | 40–232 |

| Bellator | brachychir | 10 | 0% | 100% | R | 192–245 | 27–366 | |

| Callionymidae | Foetorepus | agassizii | 7 | 0% | 100% | R | 236–304 | 91–650 |

| Caproidae | Antigonia | capros | 78 | 0% | 100% | R | 159–299 | 50–900 |

| Chaunacidae | Chaunax | pictus | 6 | 0% | 100%* | R | 247–307 | 200–1183 |

| Epigonidae | Sphyraenops | bairdianus | 6 | 0% | 100%* | R | 265–280 | 200–1750 |

| Holocentridae | Ostichthys | trachypoma | 95 | 0% | 100% | R | 161–287 | 37–550 |

| Lutjanidae | Pristipomoides | macrophthalmus | 1 | 0% | 100% | R | 210–290 | 100–550 |

| Trachichthyidae | Gephyroberyx | darwinii | 12 | 0% | 100%* | R | 167–284 | 75–1250 |

All species listed here have >75% of occurrences in the rariphotic zone (R). N = number of depth observations from combined visual and collection data. Global depth ranges are from data generated in this study and elsewhere32–34. *Indicates species that also frequently inhabit the aphotic zone at depths >500 m32–34.

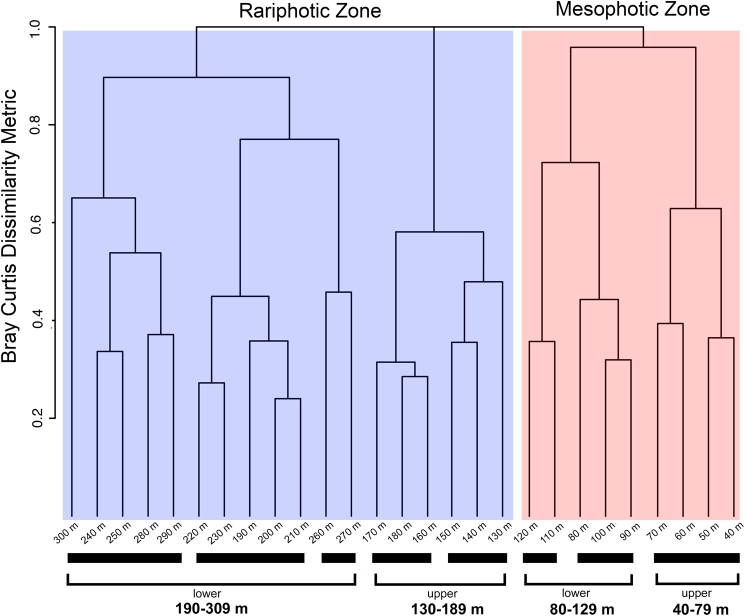

Figure 2.

Representative Caribbean fishes inhabiting the rariphotic zone off Curaçao. Haptoclinus dropi (Labrisomidae); Pontinus castor (Scorpaenidae); Anthias asperilinguis (Serranidae); Lipogramma evides (Grammatidae); Serranus notospilus (Serranidae); Polylepion sp. (Labridae). Photograph of A. asperilinguis by Patrick Colin, other photographs by C. C. Baldwin and D. R. Robertson.

Defining the boundaries of the rariphotic faunal zone

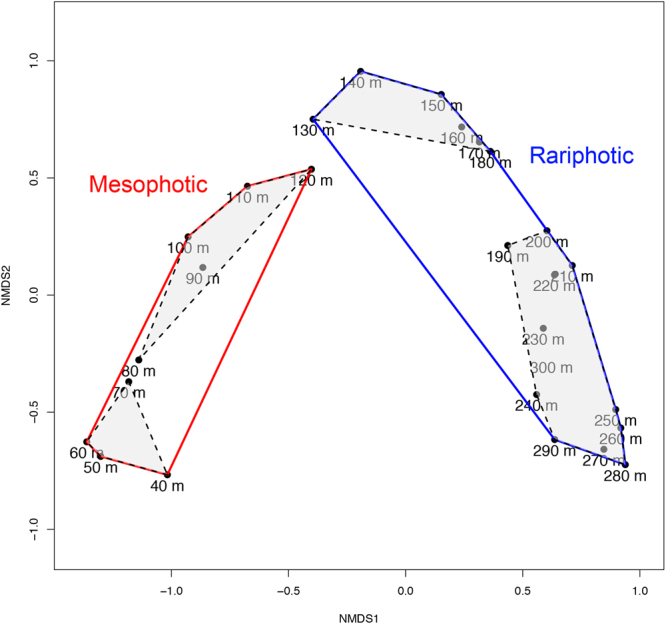

We first recognized the rariphotic fish assemblage from our anecdotal fish-observation and capture data, and a cluster analysis of our fish-depth observations shows that it is distinct from the mesophotic fish assemblage off Curaçao. A similarity profile (SIMPROF) analysis based on the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity metric revealed eight clusters, each significantly different (at p < 10−7) from the others (Figs 3 and 4): 40–79 m, 80–109 m, 110–129 m, 130–159 m, 160–189 m, 190–239, 260–279 m, and a cluster combining 240–259 m and 280–309 m depth bins. The shallowest three clusters can be combined into a ~40–129 m mesophotic zone, with a faunal break at ~80 m separating its upper (40–79) and lower (80–129) parts and providing further support for the ~80–85 m faunal break among mesophotic reef fishes previously identified by a rebreather study at Curaçao7. We group the remaining clusters into the rariphotic zone (~130–309 m), with a division between the two most dissimilar sections at ~190 m delineating upper (130–189) and lower (190–309) sections. Faunal breaks in reef-fish assemblages at ~120–130 m also have been identified off Hawaii and the Marshall Islands in the Pacific, as well as in the Gulf of Mexico8,10,31, and the ~190 m break between upper and lower rariphotic faunas at Curaçao is at the same depth as a faunal break recently identified in a study of Gulf of Mexico fishes based on depth maxima and minima10. The displacement of the 260–279 m depth group outside the 240–309 m cluster (Fig. 3) likely is an artefact attributable to low numbers in the 260–279 m bin of species that are common in adjacent shallower and deeper bins, and the sensitivity of the analysis to small differences, due to relatively small sample sizes (Fig. 1).

Figure 3.

Hierarchical clustering dendrogram from the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity analysis of 4,436 depth observations of fishes between 40 and 309 m off Curaçao. Thick solid black lines below clusters indicate groups that have significantly (p < 10−7) distinct faunal communities based on a SIMPROF analysis. Depth bins are 10-m intervals labeled by the minimum depth in each interval (e.g., “100 m” = 100–109 m).

Figure 4.

Nonmetric multidimensional scaling ordination (MDS) plot derived from the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity analysis. Red and blue polygons represent mesophotic and rariphotic zones, respectively. Shaded polygons represent upper and lower mesophotic and rariphotic sections. The two zones and four sections were derived from eight significantly different (p < 10−7) clusters in the SIMPROV analysis. Each a posteriori zone and section is significantly distinct (PERMANOVA, p < 0.01).

Although the data could be interpreted as supporting between three and eight distinct faunal zones, the four clusters (40–79 m upper mesophotic, 80–129 m lower mesophotic, 130–189 m upper rariphotic, and 190–309 m lower rariphotic) are significantly distinct (p < 0.01) and highly dissimilar (95–99%) from one another (Figs 3 and 4). The strongest breaks among all of the partitions occur between the mesophotic and rariphotic clusters, at 129–130 m, and between the upper and lower rariphotic clusters, at 189–190 m (Figs 3 and 4). Hence two zones, mesophotic and rariphotic—each with upper and lower sections—adequately explain the data and provide the simplest classification of faunal zones.

The key fish species responsible for divisions between the upper and lower mesophotic, lower mesophotic and upper rariphotic, and upper and lower rariphotic at Curaçao are listed in Table 4. Clepticus parrae (Labridae), Paranthias furcifer (Serranidae), Chromis cyanea, and C. multilineata (Pomacentridae), all of which are common altiphotic species, dominate the upper mesophotic relative to the lower mesophotic. Bullisichthys caribbaeus, Pronotogrammus martinicensis, Liopropoma mowbrayi (Serranidae), Antilligobius nikkiae (Gobiidae), and Chromis cf. enchrysura predominantly define the lower mesophotic relative to the upper mesophotic. Pronotogrammus martinicensis becomes more abundant in the upper rariphotic and, along with Palatogobius incendius (Gobiidae) and Symphysanodon octoactinus (Symphysanodontidae), drives the separation between the upper rariphotic relative to the lower mesophotic. Key lower-mesophotic species driving the separation from the upper rariphotic include some of the same species that separate the upper and lower mesophotic (B. carribaeus, A. nikkiae, L. mowbrayi, and C. cf. enchrysura) but also C. insolata, C. scotti, and Serranus luciopercanus (Serranidae). Relative to the lower rariphotic, recognition of the upper rariphotic is driven by some species that also distinguish the upper rariphotic and lower mesophotic (P. martinicensis, P. incendius, and S. octoactinus) but also by several additional species of Serranidae (Liopropoma aberrans, L. olneyi, Gonioplectrus hispanus, Serranus notospilus, and Baldwinella vivanus). Chrionema squamentum (Percophidae) and Symphysanodon berryi drive the separation of the lower and upper rariphotic.

Table 4.

SIMPER analysis results showing the relative Bray-Curtis contributions of top ten species driving differences between adjacent depth zones.

| Species | Contribution to Bray-Curtis | Avg. abundance shallower zones (transformed) | Avg. abundance deeper zones (transformed) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upper mesophotic vs Lower mesophotic | |||

| Bullisichthys caribbaeus | 0.060 | 0.000 | 12.643 |

| Clepticus parrae | 0.054 | 13.028 | 1.616 |

| Antilligobius nikkiae | 0.054 | 0.000 | 11.701 |

| Paranthias furcifer | 0.039 | 9.918 | 1.911 |

| Pronotogrammus martinicensis | 0.036 | 0.000 | 8.049 |

| Liopropoma mowbrayi | 0.030 | 2.329 | 8.344 |

| Chromis cf. enchrysura | 0.027 | 0.750 | 6.210 |

| Chromis cyanea | 0.026 | 5.114 | 0.000 |

| Chromis multilineata | 0.025 | 4.672 | 0.000 |

| Canthigaster jamestyleri | 0.025 | 3.464 | 4.189 |

| Lower mesophotic vs Upper rariphotic | |||

| Bullisichthys caribbaeus | 0.052 | 12.643 | 1.850 |

| Antilligobius nikkiae | 0.047 | 11.701 | 1.980 |

| Palatogobius incendius | 0.038 | 5.124 | 5.804 |

| Liopropoma mowbrayi | 0.037 | 8.344 | 0.779 |

| Pronotogrammus martinicensis | 0.035 | 8.049 | 12.683 |

| Chromis insolata | 0.032 | 6.137 | 0.000 |

| Serranus luciopercanus | 0.026 | 5.884 | 0.655 |

| Symphysanodon octoactinus | 0.026 | 0.000 | 5.208 |

| Chromis scotti | 0.026 | 4.984 | 0.000 |

| Chromis cf enchrysura | 0.025 | 6.210 | 1.171 |

| Upper rariphotic vs. Lower rariphotic | |||

| Pronotogrammus martinicensis | 0.087 | 12.683 | 1.764 |

| Palatogobius incendius | 0.045 | 5.804 | 0.144 |

| Chrionema squamentum | 0.039 | 0.845 | 5.482 |

| Symphysanodon octoactinus | 0.039 | 5.208 | 2.266 |

| Liopropoma olneyi | 0.037 | 5.169 | 0.493 |

| Gonioplectrus hispanus | 0.034 | 4.594 | 0.349 |

| Symphysanodon berryi | 0.028 | 1.477 | 4.710 |

| Serranus notospilus | 0.026 | 3.588 | 2.495 |

| Liopropoma aberrans | 0.024 | 3.087 | 0.144 |

| Baldwinella vivanus | 0.023 | 3.403 | 1.433 |

Although we lack the data necessary to identify the depth of a faunal break between rariphotic reef fishes and deep-sea fishes at Curaçao, the lower limit of the rariphotic may lie below 309 m. The global depth ranges of many of the Curaçao rariphotic reef fishes extend to 300–500 m, whereas few occur much deeper (Table 3 and references therein). Further, 500 m represents the approximate upper limit of the depth ranges of species in many Caribbean deep-sea families. For example, in the northeastern Caribbean, representatives of the demersal deep-sea fish families Halosauridae, Nettastomatidae, Ateleopodidae, Polymixiidae, Berycidae, Zeniontidae, and Draconettidae were observed at minimum depths of approximately 500 m during recent extensive ROV surveys24.

Taxonomic composition of the rariphotic fish assemblage

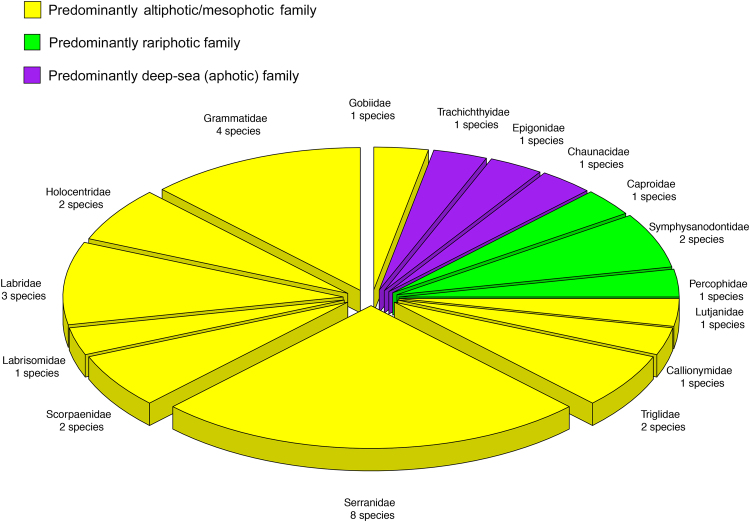

The mesophotic reef-fish fauna at Curaçao does not transition directly to one composed of deep-sea taxa. Forty-two of the 71 species of demersal Caribbean fishes in our data set have at least 25% of their depth distribution in the rariphotic—i.e., >130 m (Tables 1–3, Fig. 1). Eleven of those are mesophotic/rariphotic overlap species (Table 2), and 31 are primarily or exclusively rariphotic (Table 3). Those 31 species belong to 16 families, 10 of which (Callionymidae, Gobiidae, Grammatidae, Holocentridae, Labridae, Labrisomidae, Lutjanidae, Scorpaenidae, Serranidae, and Triglidae) primarily comprise species that inhabit altiphotic and mesophotic depths32–34 (Fig. 5). Three of the 16 families (Caproidae, Percophidae, and Symphysanodontidae) typically are found at rariphotic depths (~130 to as deep as 500 m or more32–34 – Fig. 5). Only three families (Chaunacidae, Epigonidae, and Trachichthyidae), each with a single species at Curaçao, primarily comprise species that are typical deep-sea inhabitants whose depth ranges extend far deeper than 500 m32–34 (Fig. 5). The Serranidae, with eight rariphotic species, the Grammatidae (4), and the Labridae (3) are the most common rariphotic families (Fig. 5).

Table 2.

Fishes that primarily overlap the mesophotic (40–129 m) and rariphotic (130 to at least 309 m) zones based on visual observations and specimens collected between 40 and 309 m off Curaçao.

| Family | Genus | species | N | % in Mesophotic | % in Rariphotic | Faunal Zone Assignment off Curaçao | Depth Range off Curaçao (m) | Global Depth Range (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apogonidae | Apogon | gouldi | 18 | 44% | 56% | R/M | 102–157 | 55–262 |

| Gobiidae | Palatogobius | incendius | 316 | 70% | 30% | R/M | 117–205 | 117–158 |

| Varicus | decorum | 3 | 33% | 66% | R/M | 99–220 | 99–251 | |

| Chaetodontidae | Prognathodes | guyanensis | 28 | 36% | 64% | R/M | 97–216 | 60–250 |

| Grammatidae | Lipogramma | levinsoni | 25 | 40% | 60% | R/M | 91–154 | 91–154 |

| Labridae | Decodon | n. sp. | 8 | 50% | 50% | R/M | 97–181 | 97–181 |

| Priacanthidae | Pristigenys | alta | 11 | 36% | 64% | R/M | 73–183 | 5–300 |

| Serranidae | Centropristis | fuscula | 13 | 62% | 38% | R/M | 48–245 | 20–308 |

| Choranthias | tenuis | 22 | 59% | 41% | R/M | 94–301 | 55–915 | |

| Liopropoma | aberrans | 38 | 42% | 58% | R/M | 98–241 | 89–241 | |

| Pronotogrammus | martinicensis | 559 | 38% | 62% | R/M | 85–293 | 55–300 |

Figure 5.

Families of rariphotic reef-fish species off Curaçao analyzed in this study and the predominant depth category to which each can be assigned. Altiphotic/mesophotic families are those for which depth ranges of members are predominantly shallower than 130 m32–34. Rariphotic families are those predominantly inhabiting depths > 130 to as deep as 500 m32–34. Deep-sea (aphotic) families are those typically inhabiting depths > 500 m24,32–34.

The 31 predominantly rariphotic species at Curaçao belong to 23 genera (Table 3), only three of which—Chaunax, Gephyroberyx, and Sphyraenops—are primarily aphotic, deep-sea taxa32–34. Lipogramma, with four rariphotic species, Bellator (2), Liopropoma (2), Pontinus (2), Serranus (2), and Symphyanodon (2) are the most common rariphotic genera (Table 3).

Thus, deep-sea taxa contribute little to the rariphotic reef-fish assemblage at Curaçao, which is dominated overwhelmingly by primarily altiphotic and mesophotic families. Furthermore, at least some rariphotic fishes not only are members of predominantly altiphotic taxa but are evolutionarily derived from shallow-reef ancestors. A recent study of ours indicates that several Caribbean rariphotic goby lineages represent recent (~10–14 mya) evolutionary transitions from shallow ancestors, with subsequent species radiations by rariphotic lineages in some genera35. Our inspection of relationships in other recently published phylogenies suggests that similar shallow-to-deep habitat transitions likely occurred in other Caribbean fish genera that include rariphotic species, including Lipogramma (Grammatidae), Haptoclinus (Labrisomidae), and both Decodon and Polylepion (Labridae). In each case, the rariphotic species are nested deep within clades of altiphotic or mesophotic species30,36–38 (supplemented with our unpublished sequence data for the rariphotic genus Haptoclinus). Other genera of rariphotic reef fishes, such as Pristipomoides (and closely related species in the Lutjanidae subfamily Etelinae), and Corniger and Ostichthys (Holocentridae subfamily Myripristinae), belong to clades primarily containing rariphotic and mesophotic taxa that, collectively, are sister groups to clades of altiphotic taxa37,39,40. Few studies have investigated historical depth transitions between shallow- and deep-reef taxa. Most research on the general structure of tropical reef-fish faunas at the regional level has focused on the phylogeography of shallow faunas and the relationship between faunal structure and the usage of reefs vs. other habitats41–44. However, research attention needs to be expanded to resolving phylogenetic relationships among reef-fish assemblages inhabiting different depth zones, as that is central to understanding the evolutionary origins and current composition of local and regional reef-fish faunas inhabiting shallow as well as deep reefs.

The rariphotic reef-fish fauna described here is not restricted to Curaçao. Similarly large data sets are needed to determine the depth breaks between mesophotic and rariphotic fish faunas at other Caribbean sites, and establish the lower limit of the rariphotic zone. However, preliminary observations and collections between ~40 and 300 m off Bonaire, Dominica, Honduras, and St. Eustatius indicate that much of the Curaçao rariphotic fauna is widespread throughout the Caribbean. Not surprisingly, we and others3,7,13,22,23 (and see species range-maps34) have observed the same for the Caribbean mesophotic fish fauna. Other ocean basins also appear to accommodate a rariphotic fish fauna; for example, in the Hawaiian Archipelago and Indo-west Pacific, some species of Chromis (Pomacentridae), Parapercis (Pinguipedidae), Bodianus (Labridae), Scorpaena (Scorpaenidae), and Anthias, Odontanthias, and Sacura (Serranidae) have the upper limits of their depth ranges between 130 and 180 m8,32.

Faunal depth boundaries

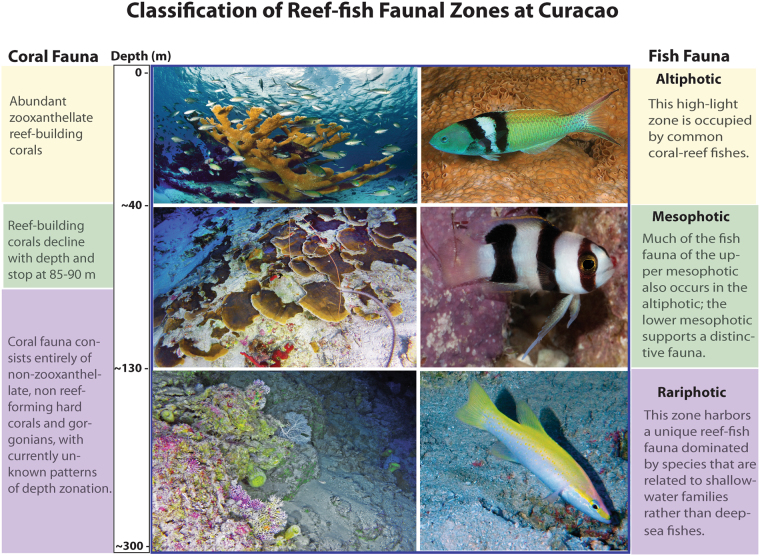

The boundary between mesophotic and rariphotic fish communities occurs at Curaçao at ~130 m, shallower than the 150-m depth typically considered as the lower boundary of the mesophotic zone2,3,7,9,11. However, the lower limits of zooxanthellate coral-reef development (which has traditionally been used to define the lower boundary of the mesophotic zone) range from ~55 to 133 m15,45,46 in the wider Caribbean area, and the lower limits of such reef corals in our study area at Curaçao are ~85–90 m16,47 (Fig. 6). The latter depth range is similar to the ~80–85 m faunal break between upper and lower mesophotic reef-fish assemblages at Curaçao revealed in our analysis and elsewhere7. At our study site on the leeward coast of Curaçao, in addition to a steep drop-off in bottom topography beginning at 7–15 m, a second vertical drop-off begins at ~80–90 m7,48,49, thus dramatically reducing light levels7, both of which may influence faunal boundaries of corals and fishes. Beyond that drop-off to ~309 m at Curaçao, the slope consists of a series of vertical to moderately sloped cliffs and ridges interrupted by rubble and sand beaches. Faunal assemblages of benthic invertebrates have not been characterized at Curaçao below the ~85–90 m limits of zooxanthellate coral growth, but we have observed non-zooxanthellate, non-reef-building hard corals and a diversity of gorgonians below that depth zone (Fig. 6). Other than the correlation between the depths of the lower limit of zooxanthellate coral growth and the faunal break between upper and lower mesophotic fish assemblages, there are no obvious associations between fish-faunal boundaries and benthos/bottom topography at Curaçao. In the northern Gulf of Mexico, typical mesophotic reef fishes extend their depth ranges well below the shallow (~50 m) lower limit of zooxanthellate coral growth18, another indication of a lack of a strong association between the depth zonations of reef fishes and reef-building corals, at least in the wider Caribbean. A general ~200-m faunal changeover in the Gulf of Mexico based on the depth ranges of fishes and other taxa there may be related to environmental differences (productivity and water-current systems) between the edge of the continental shelf and slope10. However, while that Gulf possesses a broad continental shelf, no equivalent exists at Curaçao, where the reef drops off rapidly from near the surface to at least 300 m.

Figure 6.

Classification of faunal zones above the aphotic based on analysis of fish assemblages at Curaçao. Representative coral and fish species are depicted for each zone. Altiphotic: (left) the zooxanthellate coral, Acropora palmata, and (right) Thalassoma bifasciatum (depth off Curaçao 0-35 m); Mesophotic: (left) a zooxanthellate plate coral, Agaricia sp., and (right) Lipogramma levinsoni (depth off Curaçao 91–154 m); Rariphotic: (left) the lace coral Stylaster sp. and gorgonian Nicella sp., and (right) Liopropoma olneyi (depth off Curaçao 112–229 m). Photos by Federico Cabello (upper left), Kevin Bryant (upper right), C. C. Baldwin, D. R. Robertson, and L. Tornabene.

Other physical water-mass features such as temperature, pressure, and dissolved oxygen also may play a role in the structuring of reef communities by depth24. We assessed potential correlations between temperature and fish-faunal structure from temperature data recorded during 319 sub dives to depths as great as 309 m in 2011–2014 (Fig. 7). Mean temperature declines gradually to ~50 m, where, during submersible dives, we often observed the upper limit of the thermocline as a shimmering layer of water. The rate of decline in mean temperature increases between ~50 and 130 m, a zone that exhibits the greatest variability in temperatures. That variability likely is due to both day-to-day fluctuations off Curaçao16 and seasonal upwelling49. Mean temperatures continue to decline gradually to 309 m, providing the 130–309 m zone with the coldest, most stable temperatures. The top of the thermocline at ~50–60 m coincides with only a minor fish-faunal break within the upper mesophotic (Fig. 3), while the zone of most rapid decline and greatest variability in temperatures is associated with the mesophotic (~40–130 m), and the coldest and most stable temperatures with the rariphotic (~130–309 m). However, any conclusions about those relationships remain tentative in light of temperature variability. Future research efforts need to scrutinize relationships between the zonation of reef fishes and temperature patterns on shallow-to-deep reef slopes at other Caribbean locations.

Figure 7.

Mean (with range and +/− one standard deviation) temperatures at 10-m intervals between the surface and 309 m recorded from 319 submersible dives off Curaçao.

Faunal depth boundaries also vary by location, as indicated by differences not only between local and global depth ranges of fish species (Tables 1–3) but also between depth ranges of zooxanthellate coral reefs in different parts of the Greater Caribbean2,15,16,18,46,50,51. If local depth ranges vary geographically, then using species’ local depth distributions, as done in this study, is likely to produce better estimates of faunal breaks than using species’ global depth ranges. Furthermore, studies at different locations with different environmental regimes that combine information on species’ local depth distributions with that on changes in environmental variables along depth gradients offer the opportunity to assess how such variables affect depth distributions of not only tropical reef fishes but also corals and other invertebrate reef taxa.

New classification of tropical reef-faunal zones

A graphical representation of reef-faunal zones based on the present study at Curaçao is shown in Fig. 6. Existing classifications for benthic faunal zones along continental shores, shelves, and slopes (i.e., littoral [intertidal], sublittoral [intertidal to 200 m], archibenthal [60–1,000 m], bathyal [200–1,000 m], abyssal [4,000–6,000 m], hadal [>6,000 m]52,53) do not delineate tropical altiphotic, mesophotic, and rariphotic faunal zones and cannot be adapted to fully describe major depth-related changes in the Curaçao reef-fish assemblage between the surface and 309 m. Open-ocean ecosystems have yet another, different classification (i.e., epipelagic/euphotic [0–200 m], mesopelagic/disphotic [200–1,000 m], bathypelagic [1,000–4,000 m], and abyssopelagic [>4,000 m]54) that is not appropriate for benthic communities. Our classification, derived from analyzing fish-faunal assemblages between 40 and 309 m, accommodates a broad rariphotic zone below the mesophotic that is populated largely by deep-living representatives of shallow-water higher taxa at Curaçao and elsewhere in the Caribbean Sea. The extent to which this classification can accommodate depth changes in assemblages of zooxanthellate and other types of corals, as well as other reef taxa at Curaçao and elsewhere, remains to be investigated. Formally classifying mesophotic and rariphotic assemblages improves the ability of scientists and the public to communicate about tropical ocean biodiversity and directs attention to one of the poorly studied marine environments, in this case a highly diverse one. Recent investigations of just a few Caribbean mesophotic and rariphotic reef ecosystems have revealed so many new species27–30,55–62 that the true amount of biodiversity in both of those zones is likely far from adequately known. Dedicated global biodiversity exploration of such ecosystems should be a major research priority. Because altiphotic, mesophotic, and rariphotic zones form a tropical depth continuum, further study of their biological and ecological interactions is needed in light of changing global ocean conditions. As mesophotic depths may serve as refugia for altiphotic inhabitants, so may rariphotic depths for mesophotic life.

Methods

Site description

Observations and collections of deep-reef fishes were conducted off the coast of Curaçao near 12.083197N, 68.899058W. The study site was chosen based on accessibility to deep-reef ecosystems very close to shore, obviating the need (and associated costs) of a research support vessel for submersible operations. The general reef characteristics of Curaçao and Bonaire are very similar and have been summarized elsewhere49. That summary agrees well with our observations from sub dives at both Islands. Coral-cover estimates for shallow reefs (<20 m) on the leeward side of Curaçao range between 16–40%63. Overall, gradually sloping shallow-reef areas drop more steeply at ~7–15 m, followed by additional vertical drop-offs beginning at 70–90 m depending on location7,16,48,64–66. Most of the deep-reef area to ~300 m at Curaçao is characterized by steep to moderately sloped cliffs interrupted by rubble and sand beaches. Cliffs were largely formed by erosion of terraces formed during periods of low sea-level during Pleistocene67. Curaçao experiences less than 500 mm of annual precipitation (http://www.meteo.cw/climate.php), and, in general, water visibility is high year-round. There were no observable differences in visibility along the deep-reef slope during our study period.

Fish observations

Observations and collections of deep-reef fishes were a major objective of ~80 dives between 2011 and 2016 made by the manned submersible Curasub (http://www.substation-curacao.com/) off the coast of Curaçao. Each dive typically lasted ~4 hours and many reached a depth near 310 m (the maximum to which Curasub is rated). Fish-sighting records and collections commenced at 40 m on each dive. Dives generally involved roving surveys, with the submersible facing the reef and moving slowly (<2 knots) laterally while simultaneously descending very slowly down the slope to a variable maximum depth. Periodic pauses were made throughout each dive for collecting specimens. Most species depth records were obtained by a pair of us seated in the front of the submersible linking our sightings of identifiable fishes to readouts from an internal digital depth gauge. These observations were supplemented with representative specimens captured using an anesthetic ejection system coupled to a suction hose that empties into a collecting chamber55. A total of 202 specimens was collected, with a special emphasis on species that are difficult to identify visually (e.g. cryptobenthic species), unfamiliar species likely to be new, and species for which tissue samples were needed for ongoing studies involving genetic analyses. Identifications of captured specimens were made using both morphology and DNA barcoding67. Fishes that could not be identified confidently visually from the sub or from investigation of captured specimens (e.g., those with problematic taxonomy) were excluded from the analysis presented here. We estimated relative sampling effort by examining the time spent at each 10-m depth band on 53 dives in 2011–2013 (Supplemental Fig. 1), and differences in sampling efforts at each depth are accounted for below under “Fish-Assemblage structure.” Guidelines for the Use of Fishes in Research co-established by the American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists (http://www.asih.org/sites/default/files/documents/publications/asf-guidelines-use-of-fishes-in-research-2013.pdf) were followed for all field-collecting activities, and fish specimens collected as part of this study were done so under Smithsonian Animal Care and Use Committee (ACUC) approval to C. C. Baldwin (ACUC #2011–07 and #2014–13).

Fish-Assemblage structure

The depth structure of fish assemblages was examined using the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity metric7,24,68,69. The 4,436 observations on 71 species were separated into 10-m bins from 40 to 309 m. The number of observations per species ranged from 1 to 559 (mean = 62.4). Sampling effort (dive time) across each 10-m depth interval was relatively uniform across most depths, but somewhat shorter at the deepest intervals. We therefore standardized species observations in each depth interval by applying a multiplier equal to the average dive time in the most heavily sampled depth interval divided by the average dive time in each respective interval. In some cases, few observations of certain species may be due to sampling bias, as small, solitary, cryptobenthic species are often overlooked in visual surveys. To avoid overemphasizing the importance of rare species in our analysis, while also controlling for extremely abundant species that sometimes occur in large schools, we applied a square-root transformation to our raw abundance data. The clustering analysis based on the Bray-Curtis metrics used the complete-linkage clustering algorithm, which seeks to maximize distance between clusters by calculating the proximity between clusters based on the two most distant objects in each cluster. Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) ordination and a hierarchical cluster dendrogram were used to visualize community structure. The number of significantly distinct depth clusters was determined using Analysis of Similarity Profiles (SIMPROF) with a conservative value of alpha = 10−7 (see24,70–72). To confirm the statistical significance of depth zones that were delineated a posteriori (e.g. the upper- and lower- mesophotic and rariphotic zones, which combined clusters from the SIMPROF analysis), we used PERMANOVA73. A similarity percentage analysis (SIMPER)7,24,69,74 was used to determine which species contributed most to differences between adjacent depth zones (upper mesophotic-lower mesophotic, lower mesophotic-upper rariphotic, upper rariphotic-lower rariphotic) (Table 4).

Temperature

The Curasub is equipped with a Sensus Ultra dive data logger that records temperature at 10-second intervals during a sub dive to 0.01C with an accuracy of +/− 0.8 C. We analyzed temperature data from 319 dives made during three years (2011–2014) to as deep as 309 m.

Data availability

Raw fish-depth data analyzed during this study are included in Supplementary Table 1, and raw temperature data in Supplementary Table 2. Data used to produce temperature graph in Fig. 7 are tabulated in Supplementary Table 3.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

Research was supported by the Smithsonian Institution’s Consortium for Understanding and Sustaining a Biodiverse Planet, Competitive Grants for the Promotion of Science, NMNH Research Programs, the Herbert R. and Evelyn Axelrod Endowment Fund for systematic ichthyology, and the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute; National Geographic Society’s Committee for Research and Exploration (Grant #9102-12); and the Prince Albert II of Monaco Foundation (Grant #1801). Photograph of Anthias asperilinguis in Fig. 2 was taken during sub dives funded by the U.S. National Cancer Institute marine collections contract to Coral Reef Research Foundation. Some raw temperature data are courtesy of Substation Curaçao. Ocean Heritage Foundation/Curacao Sea Aquarium/Substation Curacao (OHF/SCA/SC) contribution number 35.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to planning the project; acquiring, analyzing, and interpreting the data; and writing the manuscript. C.C.B. and D.R.R. acquired funding to conduct the study.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-23067-1.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bongaerts P, Ridgway T, Sampayo EM, Hoegh-Guldberg O. Assessing the ‘deep reef refugia’ hypothesis: focus on Caribbean reefs. Coral Reefs. 2010;14:309–327. doi: 10.1007/s00338-009-0581-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hinderstein LM, et al. Mesophotic coral ecosystems: characterization, ecology, and management. Coral Reefs. 2010;29:247–251. doi: 10.1007/s00338-010-0614-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bejarano I, Appeldoorn RS, Nemeth M. Fishes associated with mesophotic coral ecosystems in La Parguera, Puerto Rico. Coral Reefs. 2014;33:313–328. doi: 10.1007/s00338-014-1125-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kahng SE, Copus JM, Wagner D. Recent advances in the ecology of mesophotic coral ecosystems (MCEs) Environmental Sustainability. 2014;7:72–81. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holstein DM, Smith TB, Gyory J, Paris CB. Fertile fathoms: deep reproductive refugia for threatened shallow corals. Scientific Reports. 2015;5:12407. doi: 10.1038/srep12407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker, E. K., Puglise, K. A., Harris, P. T. (Eds), Mesophotic coral ecosystems — A lifeboat for coral reefs? The United Nations Environment Programme and GRID-Arendal, Nairobi and Arendal (2016).

- 7.Pinheiro HT, et al. Upper and lower mesophotic coral reef fish communities evaluated by underwater visual censuses in two Caribbean locations. Coral Reefs. 2016;35:139–151. doi: 10.1007/s00338-015-1381-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pyle, R. L. et al. A comprehensive investigation of mesophotic coral ecosystems in the Hawaiian Archipelago. PeerJ, 10.7717/peerj.2475 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Loya Y, Eyal G, Treibitz T, Lesser MP, Appeldoorn R. Theme section on mesophotic coral ecosystems: advances in knowledge and future perspectives. Coral Reefs. 2016;35:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00338-016-1410-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Semmler, R. F., Hoot, W. C. & Reaka, M. L. Are mesophotic coral ecosystems distinct communities and can they serve as refugia for shallow reefs? Coral Reefs, 10.1007/s00338-016-1530-0 (2016).

- 11.Kahng, S., Copus, J. M. & Wagner, D. Mesophotic coral ecosystems. In: Rossi, S. (Ed.) Marine Animal Forests, 10.1007/978-3-319-17001-5_4-1 (2017).

- 12.Liddell WD, Ohlhorst SL. Hard substrata community patterns, 1–120 m, North Jamaica. Palaios. 1988;3:413–423. doi: 10.2307/3514787. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcia-Sais JR. Reef habitats and associated sessile-benthic and fish assemblages across a euphotic–mesophotic depth gradient in Isla Desecheo, Puerto Rico. Coral Reefs. 2010;29:277–288. doi: 10.1007/s00338-009-0582-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laverick, J. H., Andradi-Brown, D. A. & Rogers, A. D. Using light-dependent scleractinia to define the upper boundary of mesophotic coral ecosystems on the reefs of Utila, Honduras. PLoS ONE12, 10.1371/journal.pone.0183075 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Muñoz, R. C. et al. Conventional and technical diving surveys reveal elevated biomass and differing fish community composition from shallow and upper mesophotic zones of a remote United States coral reef. PLoS ONE12, https://doi.org/10.1371/ journal.pone.0188598 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Bongaerts P, et al. Deep down on a Caribbean reef: lower mesophotic depths harbor a specialized coral-endosymbiont community. Scientific Reports. 2015;5:1–9. doi: 10.1038/srep07652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosa MR, et al. Mesophotic reef fish assemblages of the remote St. Peter and St. Paul’s Archipelago, Mid-Atlantic Ridge, Brazil. Coral Reefs. 2016;35:113–123. doi: 10.1007/s00338-015-1368-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dennis GD, Bright TJ. Reef fish assemblages on hard banks in the northwestern Gulf of Mexico. Bulletin of Marine Science. 1988;43:280–307. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bryan DR, Kilfoyle K, Gilmore RG, Jr., Spieler RE. Characterization of the mesophotic reef fish community in south Florida, USA. Journal of Applied Ichthyology. 2013;29:108–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0426.2012.02055.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feitoza BM, Roa RS, Rocha LA. Ecology and zoogeography of deep-reef fishes in northeastern Brazil. Bulletin of Marine Science. 2005;76:724–742. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fukunaga A, Kosaki RK, Wagner D, Kane C. Structure of mesophotic reef fish assemblages in the northwestern Hawaiian Islands. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0157861. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Colin PL. Observations and collections of deep-reef fishes off the coasts of Jamaica and British Honduras (Belize) Marine Biology. 1974;24:29–38. doi: 10.1007/BF00402844. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Colin PL. Observations of deep-reef fishes in the Tongue of the Ocean, Bahamas. Bulletin of marine Science. 1976;26:603–605. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quattrini, A. M., Demopoulos, A. W. J., Singer, R., Roa-Varon, A. & Chaytor, D. Demersal fish assemblages on seamounts and other rugged features in the northeastern Caribbean. Deep Sea Research Part I, 10.1016/j.dsr.2017.03.009 (2017).

- 25.Weiss KR. Naturalist Richard Pyle explores the mysterious, dimly lit realm of deep coral reefs. Science. 2017;355:900–904. doi: 10.1126/science.355.6328.900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gress, E. et al. Lionfish (Pterois sp.) invade the upper bathyal zone in the western Atlantic. PeerJ, 10.7287/peerj.preprints.2987v1 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Baldwin CC, Robertson DR. A new Haptoclinus blenny (Teleostei, Labrisomidae) from deep reefs off Curaçao, southern Caribbean, with comments on relationships of the genus. ZooKeys. 2013;306:71–81. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.306.5198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baldwin CC, Johnson GD. Connectivity across the Caribbean Sea: DNA barcoding and morphology unite an enigmatic fish larva from the Florida Straits with a new species of sea bass from deep reefs off Curaçao. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(5):e97661. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baldwin CC, Robertson DR. A new Liopropoma sea bass (Serranidae: Epinephelinae: Liopropomini) from deep reefs off Curaçao, southern Caribbean, with comments on depth distributions of western Atlantic liopropomins. Zookeys. 2014;409:71–92. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.409.7249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baldwin CC, Robertson DR, Nonaka A, Tornabene L. Two new deep-reef basslets (Teleostei: Grammatidae: Lipogramma), with comments on the eco-evolutionary relationships of the genus. Zookeys. 2016;638:45–82. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.638.10455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thresher RE, Colin PL. Trophic structure, diversity and abundance of fishes of the deep reef (30-300 m) at Enewetak, Marshall Islands. Bulletin of Marine Science. 1986;38:253–272. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Froese, R., Pauly, D. (Eds). FishBase. World Wide Web electronic publication, www.fishbase.org, version (02/2017).

- 33.IUCN Red List. World Wide Web electronic publication, www.iucnredlist.org/search (2016-3).

- 34.Robertson, D. R. & Van Tassell, J. Shorefishes of the Greater Caribbean: online information system. Version 1.0 Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Balboa, Panamá, http://biogeodb.stri.si.edu/caribbean/en/pages (2015).

- 35.Tornabene, L., Van Tassell, J. L., Robertson, D. R. & Baldwin, C. C. Repeated invasions into the twilight zone: evolutionary origins of a novel assemblage of fishes from deep Caribbean reefs. Molecular Ecology25, 3662–3682. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Betancur-R., R. et al. The tree of life and a new classification of bony fishes. PLOS Currents Tree of Life Edition1, 10.1371/currents.tol.53ba26640df0ccaee75bb165c8c26288 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Betancur-R, R. et al. Phylogenetic classification of bony fishes. BMC Evolutionary Biology17, 10.1186/s12862-017-0958-3 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Lin H, Hastings PA. Evolution of a Neotropical marine fish lineage (Subfamily Chaenopsinae, Suborder Blennioidei) based on phylogenetic analysis of combined molecular and morphological data. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2011;60:236–248. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2011.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gold JR, Voelker G, Renshaw MA. Phylogenetic relationships of tropical western Atlantic snappers in the subfamily Lutjaninae (Lutjanidae: Perciformes) inferred from mitochondrial DNA sequences. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 2011;102:915–929. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2011.01621.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dornberg A, et al. Molecular phylogenetics of squirrelfishes and soldierfishes (Teleostei: Beryciformes: Holocentridae): Reconciling more than 100 years of taxonomic confusion. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2012;65:727–738. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2012.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bellwood DR. Reef fish biogeography: habitat associations, fossils and phylogenies. Proceedings of the 8th International Coral Reef Symposium. 1997;1:379–385. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bellwood, D. R., Wainwright, P. C. The history and biogeography of fishes on coral reefs. In: Sale, P. F. (Ed.), Coral Reef Fishes. Dynamics and Diversity in a Complex Ecosystem. Academic Press, pp. 5–32 (2002).

- 43.Barnes L, et al. The use of clear-water non-estuarine mangroves by reef fishes on the Great Barrier Reef. Marine Biology. 2012;159:211–220. doi: 10.1007/s00227-011-1801-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hemingson CR, Bellwood DR. Biogeographic patterns in major marine realms: function not taxonomy unites fish assemblages in reef, seagrass and mangrove systems. Ecography. 2017;40:1–8. doi: 10.1111/ecog.02974. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reed JK. Deepest distribution of Atlantic hermatypic corals discovered in the Bahamas. Proceedings of the 5th international coral reef symposium. 1985;6:249–254. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reed, J. et al. Cuba’s Twilight Zone Reefs: Remotely Operated Vehicle Surveys of Deep/Mesophotic Coral Reefs And Associated Fish Communities of Cuba, Joint Cuba-U.S. Expedition, R/V F.G. Walton Smith, May 14- June 13, 2017. NOAA CIOERT Report to NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 510 pp. Harbor Branch Oceanographic Technical Report Number 183 NOAA CoRIS website: http://www.coris.noaa.gov/geoportal/catalog/ (2017).

- 47.Hoeksema BW, Bongaerts P, Baldwin CC. High coral cover at lower mesophotic depths: a dense Agaricia community at the leeward side of Curacao, Dutch Caribbean. Marine Biodiversity. 2016;47:67–70. doi: 10.1007/s12526-015-0431-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bak RPM. Ecological aspects of the distribution of reef corals in the Netherlands Antilles. Bijdragen tot de Dierkunde. 1975;45:181–190. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Frade, P. R., Bongaerts, P., Baldwin, C. C., Bak, R. P. M. & Vermeij, M. J. A. The mesophotic coral ecosystems of Bonaire and Curaçao. In: Loya, Y., Puglise, K. & Bridge, T. Coral Reefs of the World Series: Mesophotic Coral Ecosystems. In Press. Springer.

- 50.Smith TB, et al. Benthic structure and cryptic mortality in a Caribbean mesophotic coral reef bank system, the Hind Bank Marine Conservation District, U.S. Virgin Islands. Coral Reefs. 2010;29:289–308. doi: 10.1007/s00338-009-0575-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kahng SE, et al. Community ecology of mesophotic coral reef ecosystems. Coral Reefs. 2010;29:255–75. doi: 10.1007/s00338-010-0593-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hedgpeth JW. Chapter 2: Classification of Marine Environments. Treatise on Marine Ecology and Paleoecology, Geological Society of America Memoirs. 1957;67:17–28. doi: 10.1130/MEM67V1-p17. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carney RS. Zonation of deep biota on continental margins. Oceanography and Marine Biology: An Annual Review. 2005;43:211–278. doi: 10.1201/9781420037449.ch6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kingsford, M. J. Marine Ecosystem. Encyclopaedia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. September 26, 2016, https://www.britannica.com/science/marine-ecosystem. Access date April 6, (2017).

- 55.Baldwin CC, Robertson DR. A new, mesophotic Coryphopterus goby (Teleostei, Gobiidae) from the southern Caribbean, with comments on relationships and depth distributions within the genus. Zookeys. 2015;513:123–142. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.513.9998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Baldwin CC, Pitassy DE, Robertson DR. A new deep-reef scorpionfish (Teleostei: Scorpaenidae: Scorpaenodes) from the southern Caribbean with comments on depth distributions and relationships of western Atlantic members of the genus. Zookeys. 2016;606:141–158. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.606.8590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bucher KE, Ballantine DL, Lozada-Troche C, Norris JN. Wrangelia goroniae, a new species of Rhodophyta (Ceramiales, Wrangeliaceae) from the tropical western Atlantic. Botanica Marina. 2014;57:265–280. doi: 10.1515/bot-2014-0012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Harasewych MG. Attenuiconus marileeae, a new species of cone (Gastropoda: Conidae: Puncticulinae) from Curaçao. The Nautilus. 2014;128:55–58. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Harasewych MG, Temkin I. The Miocene genus Mantellina (Bivalvia: Limidae) discovered living on the deep reefs off Curacao, with the description of a new species. Journal of Molluscan Studies. 2015;81:442–454. doi: 10.1093/mollus/eyv021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lemaitre, R., Felder, D. L. & Poupin, J. Discovery of a new micro-pagurid fauna (Crustacea: Decapoda: Paguridae) in the Lesser Antilles, Caribbean Sea. Zoosystema39, 151–195.

- 61.Tornabene, L. et al. Molecular phylogeny, analysis of discrete character evolution, and submersible collections facilitate a new classification for a diverse group of gobies (Teleostei: Gobiidae: Gobiosomatini: Nes subgroup), with descriptions of nine new species. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 10.1111/zoj.12394 (2016).

- 62.Tornabene L, Robertson DR, Baldwin CC. Varicus lacerta, a new species of goby (Teleostei, Gobiidae, Gobiosomatini, Nes subgroup) from a mesophotic reef in the southern Caribbean. Zookeys. 2016;596:143–156. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.596.8217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.WAITT Institute. The State of Curaçao’s Coral Reefs: Marine Scientific Assessment, http://waittinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Marine-Scientific-Assessment_May-2017-Part1.pdf.

- 64.Van Duyl FC. Atlas of the living reefs of Curaçao and Bonaire (Netherlands Antilles) Publ Found Sci Res Surinam Neth Antilles. 1985;117:1–38. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Trembanis, A. C., Forrest, A. L., Keller, B. M. & Patterson, M. R. Mesophotic Coral Ecosystems: A Geoacoustically Derived Proxy for Habitat and Relative Diversity for the Leeward Shelf of Bonaire, Dutch Caribbean. Frontiers in Marine Science4 (2017).

- 66.De Buisonje, P. H. Neogene and Quaternary geology of Aruba, Curaçao and Bonaire. Utrecht (1974).

- 67.Weigt, L. A., Driskel, A. C., Baldwin, C. C. & Ormos, A. DNA barcoding fishes. In: Kress, W. J., Erickson, D. L. (Eds) DNA Barcodes: Methods and Protocols, Methods in Molecular Biology858, 109–126 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 68.Bray JR, Curtis JT. An ordination of the upland forest communities of southern Wisconsin. Ecological Monnographs. 1957;27:325–349. doi: 10.2307/1942268. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ross SW, Rhode M, Viada ST, Mather R. Fish species associated with shipwreck and natural hard-bottom habitats from the middle to outer continental shelf of the Middle Atlantic Bight near Norfolk Canyon. Fishery Bulletin. 2016;114:45–57. doi: 10.7755/FB.114.1.4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Clarke KR, Somerfield PJ, R. Gorley N. Testing of null hypotheses in exploratory community analyses: similarity profiles and biota-environment linkage. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. 2008;366:56–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2008.07.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Majewski AR, et al. Marine fish community structure and habitat associations on the Canadian Beaufort shelf and slope. Deep-Sea Research I. 2017;121:159–182. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr.2017.01.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Quattrini AM, et al. A phylogenetic approach to octocoral community structure in the deep Gulf of Mexico. Deep-Sea Research II. 2014;99:92–102. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2013.05.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Anderson MJ. A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Austral Ecology. 2001;26:32–46. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Clarke KR. Non-parametric multivariate analyses of changes in community structure. Australian Journal of Ecology. 1993;18:117–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9993.1993.tb00438.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Raw fish-depth data analyzed during this study are included in Supplementary Table 1, and raw temperature data in Supplementary Table 2. Data used to produce temperature graph in Fig. 7 are tabulated in Supplementary Table 3.