Abstract

Background & objectives:

The in vitro assays for susceptibility of Plasmodium falciparum to antimalarial drugs are important tools for monitoring drug resistance. During the present study, efforts were made to establish long-term continuous in vitro culture of Indian field isolates of P. falciparum and to determine their sensitivity to standard antimalarial drugs and antibiotics.

Methods:

Four (MZR-I, -II, -III and -IV) P. falciparum isolates were obtained from four patients who showed artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) from Mizoram, a north-eastern State of India, and characterized for their in vitro susceptibility to chloroquine diphosphate (CQ), quinine hydrochloride dehydrate, mefloquine, piperaquine, artemether, arteether, dihydro-artemisinin (DHA), lumefantrine and atovaquone and antibiotics, azithromycin and doxycycline. These patients showed ACT treatment failure. Two-fold serial dilutions of each drug were tested and the effect was evaluated using the malaria SYBR Green I fluorescence assay. K1 (chloroquine-resistant) and 3D7 (chloroquine-sensitive) reference strains were used as controls.

Results:

Growth profile of all field isolates was identical to that of reference parasites. The IC50 values of all the drugs were also similar against field isolates and reference parasite strains, except K1, exhibited high IC50 value (275±12.5 nM) of CQ for which it was resistant. All field isolates exhibited higher IC50 values of CQ, quinine hydrochloride dihydrate and DHA compared to reference strains. The resistance index of field isolates with respect to 3D7 ranged between 260.55 and 403.78 to CQ, 39.83 and 46.42 to quinine, and 2.98 and 4.16 to DHA, and with respect to K1 strain ranged between 6.51 and 10.08, 39.26 and 45.75, and 2.65 and 3.71. MZR-I isolate exhibited highest resistance index.

Interpretation & conclusions:

As the increase in IC50 and IC90 values of DHA against field isolates of P. falciparum was not significant, the tolerance to DHA-piperaquine (PPQ) combination might be because of PPQ only. Further study is required on more number of such isolates to generate data for a meaningful conclusion.

Keywords: Antibiotics, antimalarials, field isolates, in vitro culture, Mizoram, Plasmodium falciparum

Malaria remains one of the most widespread infectious diseases of the world. More than 85 per cent of malaria cases and 90 per cent of malaria deaths occur in Sub-Saharan Africa, mainly in young children below five years of age1. Incidences of chloroquine (CQ) resistance were first reported in the late 1950s from South-East Asia and South America2. In India, the first CQ-resistant Plasmodium falciparum case was documented in 1973 from the North-East Karbi - Anglong district of Assam3. In 1982, the National Antimalarial Drug Policy was introduced to improve malaria case management and sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP) combination was recommended as the treatment for CQ-resistant malaria4. In November 1984, mefloquine (MQ) was introduced as the first-line treatment for uncomplicated falciparum malaria in Thailand, but despite careful regulation of its use, substantial resistance was developed within five years and emerged in adjacent countries, such as Burma and Cambodia5. Western Cambodia and Thailand-Myanmar border were the regions of greatest concern because resistance to both MQ and SP emerged in this area6. To overcome the problem associated with resistant falciparum malaria, artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT), which included artesunate+MQ, artemether (ARTM)+lumefantrine (LUME) and artesunate+amodiaquine, was recommended as a first-line antimalarial treatment7,8,9,10. However, the artemisinin class of drugs have also shown signs of reduced efficacy11,12,13,14 providing a potential threat to ACT. In 1994, two randomized trials were carried out in Western Cambodia (Pailin) and North-western Thailand (Wang Pha) by Dondorp et al11, who gave two regimens of artesunate treatment i.e. 2 mg/kg/day for seven days and 4 mg/kg/day for three days, followed by 25 mg/kg of MQ given in two doses. The results revealed that median parasite clearance times were 84 and 48 h in Pailin and Wang Pha, respectively, and recrudescence occurred in 30 per cent patients receiving artesunate monotherapy and in five per cent patients receiving artesunate-MQ combination therapy in Pailin, as compared with 10 and 5 per cent, respectively in Wang Pha. However, no reduction in in vitro susceptibility was observed by Dondorp et al11. Another long-term study13 was carried out on 3202 patients in north-western border of Thailand. During this study, the patients received various artesunate-containing therapies between 2001 and 2010. The findings revealed that ‘genetically determined artemisinin resistance in P. falciparum emerged along the Thailand-Myanmar border at least eight years ago and has increased substantially and may reach in Western Cambodia in 2-6 yr13. In 2012, Amaratunga et al14 explored the involvement of malaria parasite genetics and host factors towards the development of artemisinin resistance in six districts of Pursat, Western Cambodia. They gave participants 4 mg/kg artesunate at 0, 24 and 48 h, 15 mg/kg mefloquine at 72 h and 10 mg/kg mefloquine at 96 h and assessed parasite density on thick blood films every six hours until undetectable. The parasite clearance half-life was calculated. The findings revealed artemisinin resistance in Pursat. Thus, the area in Western Cambodia, especially along the border with Thailand, is considered the world's hot spot for P. falciparum multidrug resistance15,16,17,18. A molecular marker (K13-propeller) has been developed as a tool to monitor the spread of artemisinin-resistant mutations19,20. Tun et al20 observed that in Homalin, Sagaing Region in Myanmar, 25 km from the Indian border, 21 (47%) of 45 parasite samples exhibited K13-propeller mutations. The present study was undertaken to explore in vitro chemosensitivity of four Indian field isolates of P. falciparum collected from Mizoram, a north-eastern State of India, against standard antimalarial drugs and antibiotics.

Material & Methods

This study was conducted in the division of Parasitology, CSIR-Central Drug Research Institute (CDRI), Lucknow, India.

Parasites

Field isolates: Cryopreserved vials of four field isolates (MZR-I, MZR-II, MZR-III and MZR-IV) of P. falciparum, obtained from Mizoram in 2008, were procured from ICMR-National Institute of Malaria Research (NIMR), New Delhi. The four isolates were collected from four patients who exhibited dihydro-artemisinin (DHA)-piperaquine (PPQ) combination treatment failure.

Reference strains: (i) 3D7 chloroquine (CQ) sensitive strain - This parasite strain is maintained in CSIR-CDRI. It is a clone derived from NF54 strain; the original isolate was obtained from a patient living near Schiphol Airport, Amsterdam21; (ii) K1 strain (MRA159) CQ-resistant strain - This strain was obtained from MR4, American Type Cell Culture (ATCC), Manassas, Virginia, USA.

In vitro cultivation of parasite: Four field isolates (erythrocytic stages) were revived and maintained in 5 ml culture medium (RPMI-1640; Sigma, USA, R4130-1L) at 3 per cent haematocrit suspension [human red blood cells (RBCs)]. The culture medium was prepared as described elsewhere22. AlbuMAX-II (GIBCO, New Zealand; 11021/045) 0.5 and 10 per cent foetal bovine serum (FBS, Sigma, F2442/HYCLONE, SH30396.03HI) were used as serum supplements. The cultures were maintained stationary at 37°C in a CO2 incubator (Thermo Electron Corporation, USA; water jacketed, model no. 3131) in the atmosphere of five per cent CO2 and air mixture. The per cent parasitaemia (%P) was monitored daily. The in vitro culture of both reference strains was also maintained in the laboratory.

Assessment of per cent parasitaemia (%P): The Giemsa-stained blood smears were examined under the light microscope (100×, oil immersion, Nikon, Japan). Approximately 10,000 RBCs per smear were scanned and %P was calculated as number of parasitized RBCs (PRBCs)/total number of RBCs × 100.

Assessment of growth profile of field isolates:%P of all the parasites was monitored daily to determine the comparative growth profile of field isolates (MZR-I, MZR-II, MZR-III and MZR-IV) and reference parasite strains (3D7 and K1). Three replicates were carried out for each parasite isolate.

Assessment of chemosensitivity of field isolates: Fifty and 90 per cent inhibitory concentration (IC50 and IC90) values of standard antimalarials and antibiotics were determined using malaria SYBR Green I fluorescence assay23 and compared with those obtained against 3D7 and K1 parasites.

Drugs used: Chloroquine diphosphate (CQ), quinine hydrochloride dihydrate (QUIN), mefloquine hydrochloride (MQ), PPQ, ARTM, arteether (ARTE), DHA, LUME and atovaquone (ATQ) and antibiotics, azithromycin (AZI) and doxycycline (DOXY) were used for the assessment of chemosensitivity. CQ (C6628), QUIN (Q1125), MQ (M2319) and ATQ (A7986) were purchased from Sigma while PPQ, ARTM, ARTE, DHA and LUME were obtained (as gift) from IPCA Laboratories Ltd., Mumbai. The antibiotics were purchased from Biogene, USA.

Preparation of drugs: Stock solutions (10 mM) of all the drugs was prepared in dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) except CQ and PPQ which were prepared in sterile water. The subsequent dilutions were prepared in CRPMI (RPMI-1640 with 10% FBS and 9.2 μM hypoxanthine).

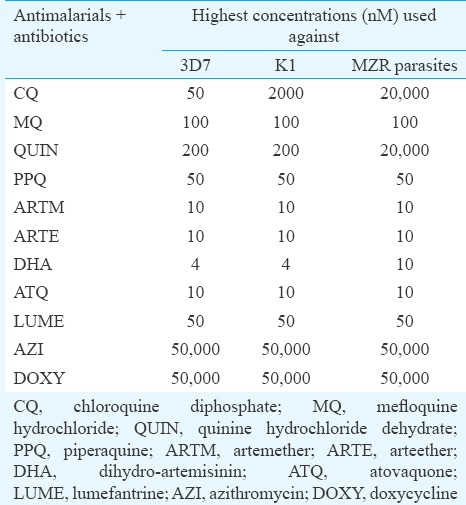

Evaluation of IC50 and IC90 values: CRPMI (50 μl) was dispensed in each well of 96-well flat bottom plate, followed by the addition of 50 μl test sample constituting 4× highest concentration in duplicate wells in row ‘B’ and 2-fold serial dilutions were made up to row ‘H'. To obtain best-fit curve, highest concentrations of the same drug varied amongst parasite strains as depicted in (Table I). The 50 μl volume from wells of row H was discarded. Subsequently, 50 μl of 2.0 per cent PRBCs suspension containing 1.0 per cent parasitaemia (with >90% ring stages) was added to each well, except four wells in row ‘A’ (A9-A12) which received two per cent non-parasitized cell suspension. The plates were incubated at 37°C in CO2 incubator for 72 h. After which, 100 μl of lysis buffer containing 2× concentration of SYBR Green I was added to each well and incubated for one hour at 37°C. The plates were examined at 485±20 nm of excitation and 530±20 nm of emission for relative fluorescence units per well using the fluorescence plate reader (FLX 800 BIOTEK). The IC50 and IC90 values (in nM) were determined using non-linear regression analysis of dose-response curves using pre-programmed excel spreadsheet. The resistance factor of MZR-I, -II, -III and -IV parasites in respect to 3D7 and K1 strains was calculated as IC50 values obtained against MZR parasites/IC50 values obtained against 3D7 or K1 parasites.

Table I.

Highest concentration of test samples used for assessment of chemosensitivity against Plasmodium falciparum

Statistical analysis: The data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA followed by multiple comparisons using Newman Keuls test (STATISTICA 7.0, StatSoft, USA) to establish significance between IC50 and IC90 values obtained against reference strains and MZR isolates.

Results

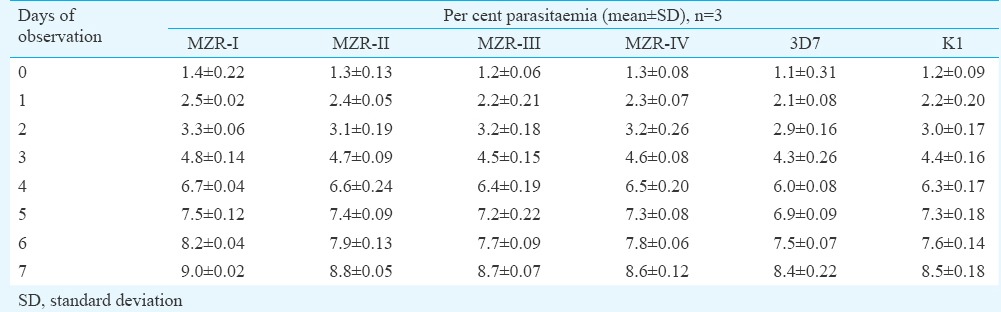

The continuous in vitro cultures of all the field isolates were successfully maintained in laboratory. Growth profile is depicted in Table II. It was evident that the initial %P of all the parasite lines ranged between 1.1 and 1.4 which rose to 8.4 and 9.0 per cent after seven days of cultivation exhibiting identical growth profile of field isolates as well as reference parasite (3D7 and K1) strains.

Table II.

Per cent parasitaemia of MZR-I, MZR-II, MZR-III and MZR-IV field isolates, and 3D7 and K1 strains of Plasmodium falciparum as observed on eight consecutive days

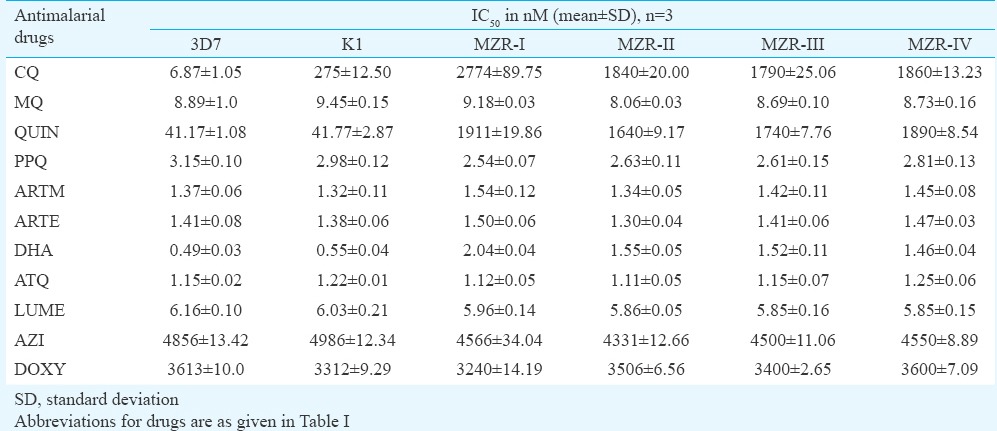

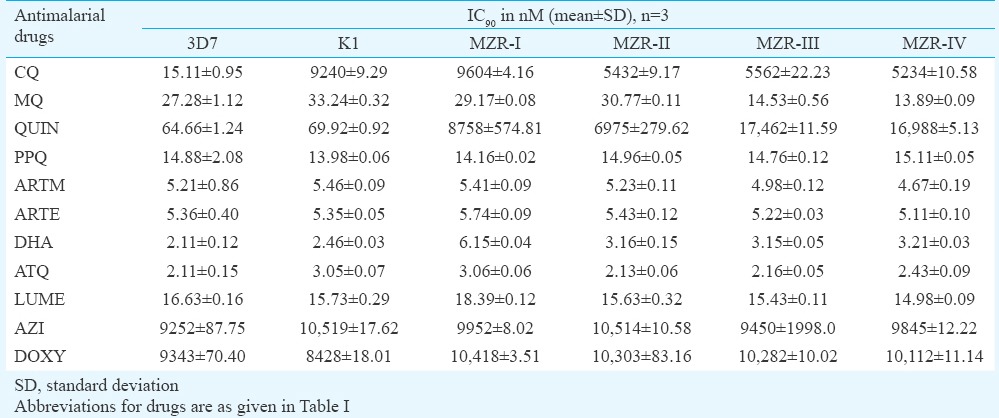

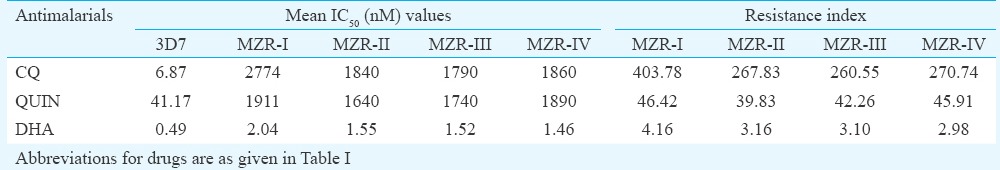

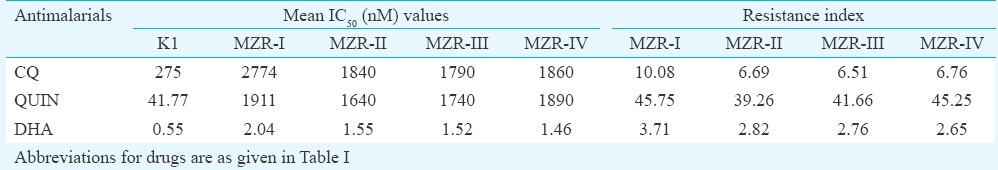

Subsequent efforts were made to determine the sensitivity of all four field isolates to nine standard antimalarials and two antibiotics. The IC50 and IC90 values (in nM) of all the antimalarials and antibiotics obtained against MZR field isolates and 3D7 and K1 parasites are depicted in Tables III and IV, respectively. The IC50 and IC90 values of all the standard antimalarials and antibiotics against MZR field isolates and reference parasite strains were almost identical, except K1 strain which exhibited high IC50 and IC90 values of CQ, for which it was resistant and all the field isolates exhibited higher IC50 and IC90 values of CQ, quinine and DHA. The IC50 and IC90 values of CQ and quinine against field isolates were significantly higher (P<0.001) when compared with 3D7 and K1 strains. The resistance index values of four field isolates to CQ, QUIN and DHA with respect to 3D7 and K1 strains are shown in Tables V and VI. It was observed that resistant index of all four field isolates, with respect to 3D7 strain, ranged between 260.55 and 403.78 to CQ, 39.83 and 46.42 to quinine and 2.98 and 4.16 to DHA, whereas the respective values to K1 strain ranged between 6.51 and 10.08, 39.26 and 45.75 and 2.65 and 3.71. MZR-I isolate exhibited highest resistance index with respect to 3D7 as well as K1 strain. The high in vitro IC50 and IC90 values of DHA (which is a metabolite of artemisinins24) correlated well with ACT treatment failure.

Table III.

IC50 values of standard antimalarials and antibiotics against laboratory maintained 3D7, K1 strains and field isolates of Plasmodium falciparum

Table IV.

IC90 values of standard antimalarials and antibiotics against laboratory maintained 3D7, K1 strains and field isolates of Plasmodium falciparum

Table V.

Resistance index of MZR field isolates in respect to 3D7 (chloroquine sensitive) strain of Plasmodium falciparum

Table VI.

Resistance index of field isolates in respect to chloroquine-resistant (K1) strain of Plasmodium falciparum

Discussion

A large number of studies have been carried out to observe in vitro susceptibility of both P. falciparum and P. vivax isolates to monitor drug resistance25,26,27,28 from different parts of the world, especially where CQ resistance is prevalent29. Wongsrichanalai et al30 have observed the prevalence of high resistance to MQ in Thai-Myanmar border region. There are many consecutive reports claiming spread of Artemisinin ART resistance in Western Cambodia11,12,14 and a recent report has provided evidence for the presence of artemisinin-resistant falciparum malaria across much of Upper Myanmar, close to the Indian border20. Artemisinins are the backbone of malaria therapy as these form the basis of ACTs where artesunate replaces quinine in the treatment of severe malaria31,32. As these isolates showed tolerance to DHA-PPQ combination therapy, we planned to explore the in vitro susceptibility of these against existing antimalarials and commonly used antibiotics and observed significantly higher IC50 (nM) and IC90 (nM) values of CQ and quinine compared to reference strains. The increase in IC50 and IC90 values of DHA was not significant.

In conclusion, our findings showed that these field isolates of P. falciparum developed resistant to CQ and quinine but not to DHA as increase in IC50 and IC90 values of DHA were not significant. These findings indicated that the tolerance to DHA-PPQ combination might be because of PPQ only. Further study is required to establish a genetic correlation with high IC50 and IC90 values of CQ and QUIN.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), New Delhi, for the financial support in the form of Senior Research Fellowship to the first author (PA) and thank Shri Mukesh Srivastava for statistical analysis. (CDRI communication number: 9256).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- 1.White NJ, Pukrittayakamee S, Hien TT, Faiz MA, Mokuolu OA, Dondorp AM, et al. Malaria. Lancet. 2014;383:723–35. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60024-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peters W. In: Chemotherapy and drug resistance in malaria. Vol. 2. London: Academic Press; 1987. Resistance in human malaria IV: 4-aminoquinolines and multiple resistance; pp. 659–786. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sehgal PN, Sharma MID, Sharma SL, Gogoi S. Resistance to chloroquine in falciparum malaria in Assam State, India. J Commun Dis. 1973;5:175–80. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anvikar AR, Arora U, Sonal GS, Mishra N, Shahi B, Savargaonkar D, et al. Antimalarial drug policy in India: Past, present & future. Indian J Med Res. 2014;139:205–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fontanet AL, Johnston DB, Walker AM, Rooney W, Thimasarn K, Sturchler D, et al. High prevalence of mefloquine-resistant falciparum malaria in Eastern Thailand. Bull World Health Organ. 1993;71:377–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nosten F, van Vugt M, Price R, Luxemburger C, Thway KL, Brockman A, et al. Effects of artesunate-mefloquine combination on incidence of Plasmodium falciparum malaria and mefloquine resistance in Western Thailand: A prospective study. Lancet. 2000;356:297–302. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02505-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nzila-Mounda A, Mberu EK, Sibley CH, Plowe CV, Winstanley PA, Watkins WM, et al. Kenyan Plasmodium falciparum field isolates: correlation between pyrimethamine and chlorcycloguanil activity in vitro and point mutations in the dihydrofolate reductase domain. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:164–9. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.1.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kublin JG, Dzinjalamala FK, Kamwendo DD, Malkin EM, Cortese JF, Martino LM, et al. Molecular markers for failure of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine and chlorproguanil-dapsone treatment of Plasmodium falciparum malaria. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:380–8. doi: 10.1086/338566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. Guidelines for the treatment of malaria. Geneva: WHO; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fall B, Diawara S, Sow K, Baret E, Diatta B, Fall KB, et al. Ex vivo susceptibility of Plasmodium falciparum isolates from Dakar, Senegal, to seven standard anti-malarial drugs. Malar J. 2011;10:310. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dondorp AM, Nosten F, Yi P, Das D, Phyo AP, Tarning J, et al. Reduced in-vivo susceptibility of Plasmodium falciparum to artesunate in Western Cambodia. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:455–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dondorp AM, Yeung S, White L, Nguon C, Day NP, Socheat D, et al. Artemisinin resistance: Current status and scenarios for containment. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8:272–80. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Phyo AP, Nkhoma S, Stepniewska K, Ashley EA, Nair S, McGready R, et al. Emergence of artemisinin-resistant malaria on the western border of Thailand: A longitudinal study. Lancet. 2012;379:1960–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60484-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amaratunga C, Sreng S, Suon S, Phelps ES, Stepniewska K, Lim P, et al. Artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum in Pursat province, Western Cambodia: A parasite clearance rate study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:851–8. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70181-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dondorp AM, Ringwald P. Artemisinin resistance is a clear and present danger. Trends Parasitol. 2013;29:359–60. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krishna S, Kremsner PG. Antidogmatic approaches to artemisinin resistance: Reappraisal as treatment failure with artemisinin combination therapy. Trends Parasitol. 2013;29:313–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Enserink M. Malaria's drug miracle in danger. Science. 2010;328:844–6. doi: 10.1126/science.328.5980.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parker DM, Carrara VI, Pukrittayakamee S, McGready R, Nosten FH. Malaria ecology along the Thailand-Myanmar border. Malar J. 2015;14:388. doi: 10.1186/s12936-015-0921-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ariey F, Witkowski B, Amaratunga C, Beghain J, Langlois AC, Khim N, et al. A molecular marker of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Nature. 2014;505:50–5. doi: 10.1038/nature12876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tun KM, Imwong M, Lwin KM, Win AA, Hlaing TM, Hlaing T, et al. Spread of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum in Myanmar: A cross-sectional survey of the K13 molecular marker. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:415–21. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)70032-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Delemarre BJ, van der Kaay HJ. Tropical malaria contracted the natural way in the Netherlands. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1979;123:1981–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Srivastava K, Singh S, Singh P, Puri SK. In vitro cultivation of Plasmodium falciparum: Studies with modified medium supplemented with ALBUMAX II and various animal sera. Exp Parasitol. 2007;116:171–4. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh S, Srivastava RK, Srivastava M, Puri SK, Srivastava K. In-vitro culture of Plasmodium falciparum: Utility of Modified (RPNI) Medium for drug-sensitivity studies using SYBR Green I assay. Exp Parasitol. 2011;127:318–21. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Woo SH, Parker MH, Ploypradith P, Northrop J, Posner G. Direct conversion of pyranose anomeric OH→F→R in the artemisinin family of antimalarial trioxane. Tetrahedron Letters. 1998;39:1533–6. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yavo W, Bla KB, Djaman AJ, Assi SB, Basco LK, Mazabraud A, et al. In vitro susceptibility of Plasmodium falciparum to monodesethylamodiaquine, quinine, mefloquine and halofantrine in Abidjan (Côte d'Ivoire) Afr Health Sci. 2010;10:111–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zatra R, Lekana-douki JB, Lekoulou F, Bisvigou U, Ngoungou EB, Ndouo FS, et al. In vitro antimalarial susceptibility and molecular markers of drug resistance in Franceville, Gabon. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12:307. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-12-307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tinto H, Bonkian LN, Nana LA, Yerbanga I, Lingani M, Kazienga A, et al. Ex vivo anti-malarial drugs sensitivity profile of Plasmodium falciparum field isolates from Burkina Faso five years after the national policy change. Malar J. 2014;13:207. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-13-207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tahita MC, Tinto H, Yarga S, Kazienga A, Traore Coulibaly M, Valea I, et al. Ex vivo anti-malarial drug susceptibility of Plasmodium falciparum isolates from pregnant women in an area of highly seasonal transmission in Burkina Faso. Malar J. 2015;14:251. doi: 10.1186/s12936-015-0769-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.The epidemiology of drug resistance of malaria parasites: Memorandum from a WHO meeting. Bull World Health Organ. 1987;65:797–816. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wongsrichanalai C, Lin K, Pang LW, Faiz MA, Noedl H, Wimonwattrawatee T, et al. In vitro susceptibility of Plasmodium falciparum isolates from Myanmar to antimalarial drugs. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001;65:450–5. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2001.65.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Checkley AM, Whitty CJ. Artesunate, artemether or quinine in severe Plasmodium falciparum malaria? Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2007;5:199–204. doi: 10.1586/14787210.5.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones KL, Donegan S, Lalloo DG. Artesunate versus quinine for treating severe malaria. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;4:CD005967. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005967.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]