Abstract

Systematic reviews are an essential tool for researchers, prevention providers and policy makers who want to remain current with the evidence in the field. Systematic review must adhere to strict standards, as the results can provide a more objective appraisal of evidence for making scientific decisions than traditional narrative reviews. An integral component of a systematic review is the development and execution of a comprehensive systematic search to collect available and relevant information. A number of reporting guidelines have been developed to ensure quality publications of systematic reviews. These guidelines provide the essential elements to include in the review process and report in the final publication for complete transparency. We identified the common elements of reporting guidelines and examined the reporting quality of search methods in HIV behavioral intervention literature. Consistent with the findings from previous evaluations of reporting search methods of systematic reviews in other fields, our review shows a lack of full and transparent reporting within systematic reviews even though a plethora of guidelines exist. This review underscores the need for promoting the completeness of and adherence to transparent systematic search reporting within systematic reviews.

Keywords: Search Reporting, Reproducibility of Results, Systematic Search, Systematic Review, Literature Review, Meta-analysis

Introduction

A systematic review employs a methodical, transparent and reproducible process to identify relevant information on a topic of interest in order to answer a specific research question. This type of review follows a specific process to locate all the available literature, assess the studies, and make an unbiased selection of studies in order to aggregate the findings to make an equitable conclusion (Hammerstrom et al., 2010; Hemingway and Brereton 2001). A systematic review is a valuable tool in collecting the vital scientific evidence necessary for developing evidence-based guidelines, making programmatic decisions, and guiding future research. The systematic search is a critical element in the review process. If certain specifications are not met during the search process, the systematic review can miss critical information, leading to inaccurate or conflicting recommendations (Counsell 1997; Patrick et al., 2004). For a systematic review to capture relevant materials on a topic, the search must be thorough, objective, and well executed (Lefebvre et al., 2009). In addition, the systematic search process must be completely transparent to afford readers the capability to evaluate the quality of the methods and results of a review as well as replicate the search for future updates (Liberati et al., 2009).

There are numerous guidelines, reporting checklists, scales or standards, and appraisal instruments that provide instructions for conducting and reporting systematic reviews (EQUATOR Network 2011; Niederstadt and Droste 2010; Sampson et al., 2008a; Sampson et al., 2009; Vandenbroucke 2009). A lack of adherence to the reporting guidelines may actually diminish, and perhaps undermine, the findings of the systematic review (Vandenbroucke 2009). An early assessment of the quality of reporting in systematic reviews by Shea et al. in 2001 compared the Quality of Reporting of Meta-Analyses (QUOROM) statement to 24 checklists published between 1984 and 1997 (Moher et al., 1999; Shea et al., 2001). While the majority of the checklists included searching, insufficient direction was provided on reporting the search method (Shea et al. 2001). Shea et al. endorsed the QUOROM statement for adoption and emphasized the Cochrane Collaboration incorporation of the Cochrane handbook criteria in their review process as a crucial component to improving the reporting within systematic reviews (Higgins et al., 2006a; Moher et al. 1999; Shea et al. 2001).

Since the publication of the Shea article in 2001 on reporting quality of systematic reviews, there has been a proliferation of tools and guidelines to assist in both the review process and in promoting the transparent description of that process. There are nine additional publications providing guidance for the systematic review process published since the QUOROM statement. These 10 guidelines (Table 1) strive for the same goal – to create transparency in the reporting of the systematic review process for evaluation, replication and future updates (Booth 2006; Centre for Reviews and Dissemination 2001; Hailey 2003; Hammerstrom et al. 2010; Higgins et al., 2006b; Institute of Medicine (IOM) 2011; Moher et al. 1999; Moher et al., 2009; Shea et al., 2007; Stroup et al., 2000). Several newer guidelines also provided more direction on reporting search methods of systematic reviews.

Table 1.

Reporting Guidelines with Search Reporting Standards (chronological by date of edition cited in the text)

| Reporting Guidelines |

Description | Year | Publication |

|---|---|---|---|

| QUOROM Statement | QUOROM Statement: Quality of Reporting of Meta-analyses | 1999 | Moher et al. 1999 |

| MOOSE Checklist | MOOSE: Meta-analyses Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology | 2000 | Stroup et al. 2000 |

| CRD Guide | Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) guide for undertaking reviews in Health Care (First Edition 1996, Second Edition 2001, Third Edition 2009) | 2001 | CRD Report Number 4 (2nd Edition) 2001 |

| HTA Checklist | Checklist for Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Reports (2003 original, 2007 version 3.2 updated online) | 2003 | Hailey et al. 2003 |

| Cochrane Collaboration Handbook | Cochrane Collaboration Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Revision 4.2.6 (update 5.0.0 in 2008 introduced search sign-off for publication) | 2006 | Higgins et al. 2006 |

| STARLITE Standard | STARLITE standards for reporting literature searches | 2006 | Booth 2006 |

| AMSTAR tool | AMSTAR measurement tool of the methodological quality of systematic reviews | 2007 | Shea et al. 2007 |

| PRISMA Statement (QUOROM Update) | PRISMA Statement: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses | 2009 | Moher et al. 2009 |

| Campbell Collaboration Guide | Campbell Collaboration Systematic Review Guide | 2010 | Hammerstrom et al. 2010 |

| IOM Statement | Institute of Medicine (IOM) Standards for Systematic Reviews | 2011 | Institute of Medicine (IOM) 2011 |

Footnote: The editions cited are not necessarily either the first editions or the current editions. They are editions cited in the text to reflect an important recommended change in practice introduced in the edition.

Research Objective

We undertook an examination of the search reporting of systematic reviews from this era (2000–2010). First, we synthesized the common search reporting elements from the 10 reporting guidelines published since 1999. We then used the Human Immunodeficiency Syndrome (HIV), Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (AIDS) and Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STD) behavioral intervention literature to examine the quality and completeness of reporting these common search elements in HIV/AIDS/STD behavioral intervention systematic reviews (DeLuca et al., 2008).

The multi-disciplinary field of HIV/AIDS and STD prevention research incorporates various subject disciplines including behavioral, biomedical, psychological, sociological and epidemiological approaches within public health research. This varied subject matter produces literature that is indexed in an expansive cross sampling of journals and databases, which affords a greater field to examine reporting styles and quality. We examined the search reporting within each eligible systematic review to answer the following questions:

How many reviews reported the databases searched?

How many reviews reported the interface (i.e., host, platform) used to access and search each database?

How many reviews clearly reported the time period of the searches?

How many reviews clearly reported the last date the search was implemented?

How many reviews reported the complete search of at least one or all databases in order to reproduce the search?

How many reviews reported which languages were included?

How many reviews reported a supplemental search component?

How many reviews reported including an experienced searcher?

METHODS

Search Methods

The search consisted of text words and index terms in three domains, (1) HIV, AIDS or STD, (2) prevention, intervention or evaluation terms, and (3) systematic reviews, literature reviews or meta-analysis. The Boolean operator “OR” was used to consolidate each domain. The “AND” operator was employed to cross-reference the three domains. We did not use the explode function on the index terms as it resulted in large number of irrelevant citations during our substantial testing process (DeLuca et al. 2008). The third domain of the systematic review search is heavily based on strategies developed by Brian Haynes and Anne McKibbon at McMaster University in Canada and strategies developed by Carol Lefebvre et al. at the UK Cochrane Centre (BMJ Evidence Based Centre 2012; Boynton et al., 1998; Haynes et al., 1994; The InterTASC Information Specialists' Sub-Group 2012; White et al., 2001). The goal of the search was to capture any article that had at least one element from each of the three domains. It was an overly inclusive search designed to capture any literature that could be incorrectly indexed or have a poorly written abstract. This method was employed to allow for exclusion at the screening level (Boynton et al. 1998; DeLuca et al. 2008).

The search for this review was first tested and created in MEDLINE (OVID) using MeSH and text words, employing truncation and proximity operators (OVID-MEDLINE [database online] 1988). The finalized MEDLINE search was adapted to the other databases using the same text words and tailoring indexing terms to the proprietary system available in PsycINFO, EMBASE, CINAHL and Sociological Abstracts (CSA ProQuest-Sociological Abstracts [database online] 2005; EBSCOhost-CINAHL [database online] 1981; OVID-EMBASE [database online] 1988; OVID-PsycINFO [database online] 1988). Search commands used on the OVID platform in MEDLINE were adapted to the other database platforms. A supplemental search was run in the Cochrane Library however, the platform available at the time permitted only a string search (The Cochrane Library 2010; The Cochrane Library 2011). The search of the Cochrane Library was considered a supplemental search since the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews is indexed in MEDLINE, EMBASE and CINAHL.

The comprehensive search was performed in May 2010 for the years 2000 – 2009. The search was re-run as an update in May 2011 in the same databases for the years 2009 – 2010 (CSA ProQuest-Sociological Abstracts [database online] 2005; EBSCOhost-CINAHL [database online] 1981; OVID-EMBASE [database online] 1988; OVID-MEDLINE [database online] 1988; OVID-PsycINFO [database online] 1988). The search was developed and implemented by two librarians with systematic search training and many years of experience in conducting systematic searches of HIV/STD literature. The complete searches as they appeared in each database are available in Appendix A.

Study Selection

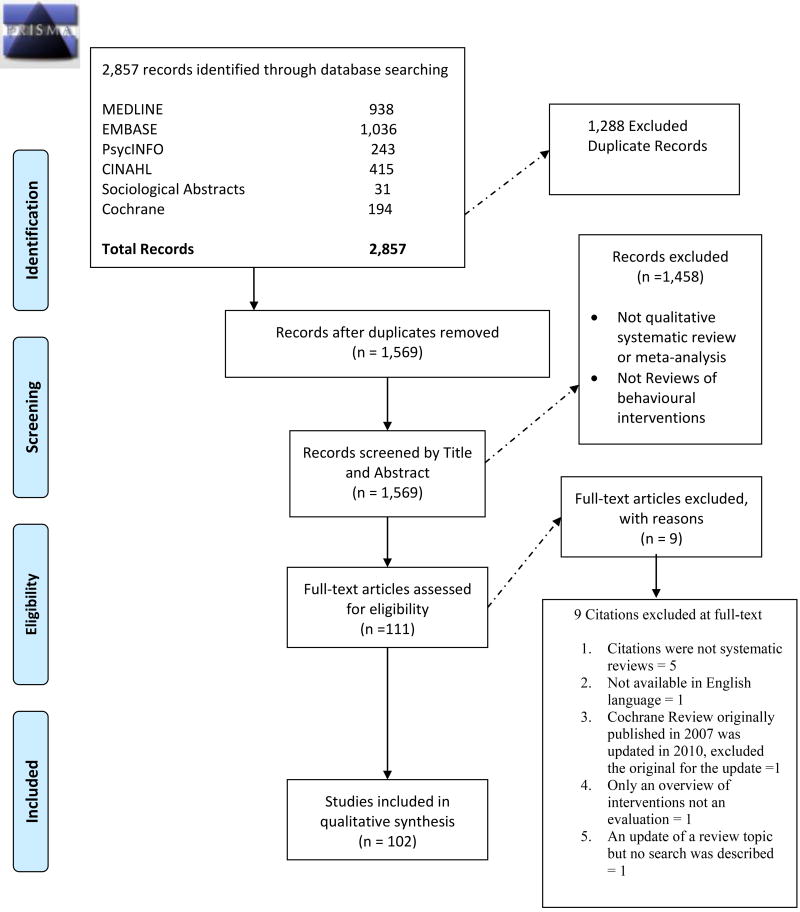

As shown on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram in Figure 1, a total of 2,857 citations were captured through the searches of the six databases. There were 1,288 duplicate records eliminated, resulting in 1,569 records to review.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram

From: Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 6(6): e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097

For more information, visit www.prisma-statement.org.

All 1,569 records were screened with the abstract, by two authors (MM, JD) using established eligibility criteria. Systematic reviews were included if they met all of the following criteria: (1) a qualitative systematic review or meta-analysis that employ a methodical process to identify a relevant literature ; (2) focused on behavioral interventions preventing the risk of contracting or spreading HIV, AIDS or STDs; and (3) available in English. Reviews were excluded if they were (1) narrative reviews that provided only an overview of specific topic with selected studies or (2) not focused on behavioral interventions to prevent contracting or spreading HIV, AIDS or STDs (e.g., drug research, mother-to-child transmission, medication adherence, STD treatment or health complications from infection, male circumcision).

After independent screening and reconciliation by the two coders, there were 111 citations eligible for full report screening based on the review criteria. There were 1,458 citations excluded from the review for not meeting the eligibility criteria. Two authors independently screened all 111 full reports using the standardized coding form, and each article was then reconciled for consensus. After reviewing the 111 citations with the full report there was an agreement to exclude nine more papers from this review as shown in Figure 1 (Auerbach et al., 2006; Bateganya et al., 2007; Chen 2007; DesJarlais and Semaan 2005; Fisher and Smith 2009; Herbst and Task Force on Community Preventive Services 2007; Hoffmann et al., 2006; Ross 2010; Takacs and Demetrovics 2009).

Coding

A total of 102 systematic reviews were included in the review and coded with a standardized document developed after synthesizing the common reporting elements of 10 reporting checklists (Booth 2006; Centre for Reviews and Dissemination 2009; Hammerstrom et al. 2010; Health Technology Assessment 2007; Institute of Medicine (IOM) 2011; Lefebvre et al., 2008; Moher et al. 1999; Moher et al. 2009; Shea et al. 2007; Stroup et al. 2000). The coding document collected information on search specifics that answered questions about the databases searched, name of interface or host/platform, years covered, date of last search, complete search strategy as it appeared on the platform, language limits, supplemental search and inclusion of an individual with search experience. The reviewing pair independently abstracted the data from the 102 papers and reconciled any discrepancies. The results are presented to show the overall findings for the 102 reviews as well as the results of the nine reviews published by the Cochrane Collaboration which should meet the Cochrane Handbook search reporting standards at the time of publication (Higgins et al. 2006b; Lefebvre et al. 2008; Lefebvre et al. 2009)

RESULTS (See Tables 4–6)

Our synthesis of the 10 guidelines with search reporting instructions from the QUOROM in 1999 to the IOM standard for systematic reviews of 2011 (Table 2) yields eight common reporting elements: databases, name of host/platform, years covered by the search, date last search was run, complete search strategy, language limits, supplemental search and qualification of the searcher (Booth 2006; Centre for Reviews and Dissemination 2009; Hammerstrom et al. 2010; Health Technology Assessment 2007; Institute of Medicine (IOM) 2011; Lefebvre et al. 2008; Liberati et al. 2009; Moher et al. 1999; Moher et al. 2009; Shea et al. 2007; Stroup et al. 2000). Table 3 elaborates on each common element based on the descriptions provided in the 10 guidelines. As seen in Table 4, two thirds of 102 reviews were published in 2006 or later when the majority of reporting guidelines were being published or updated. The same pattern is seen for the nine Cochrane reviews. The 102 reviews were published in 51 journals. Forty-three journals (84%) published only one or two reviews that accounted for 50% of included reviews (51/102). Four journals (8%) published 9 or more reviews that accounted for 36% of included reviews. Nine reviews were published by the Cochrane Collaboration.

Table 2.

Search Reporting Guidelines Checklist

| Reporting Guidelines | Year | Critical Reporting Elements | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Databases | Name of Interface (Host/platform) |

Years covered by search |

Date last search was run |

Complete Search Strategy |

Language Limits |

Supplemental Search |

Qualification of searcher |

||

| QUOROM Statement: Quality of Reporting of Meta-analyses | 1999 | X | X | X | X | ||||

| MOOSE: Meta-analyses Of Obstervational Studies in Epidemiology | 2000 | X | Search Software (name, version) | X | Provide search strategy | X | X | X | |

| STARLITE Standards for Reporting Literature Searches | 2006 | X | platforms and vendors | X | Sample search strategy from 1 or more main databases | X | X | ||

| Checklist for Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Reports (Orig. 2003, 2007 Updated online) | 2007 | X | X | Available "On Request" | X | ||||

| AMSTAR Measurement Tool of the methodological quality of systematic reviews | 2007 | X | X | If feasible provide search strategy | X | X | |||

| Cochrane Collaboration Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (rev. 5.0.0)[update to search section] | 2008 | X | X | X | Full Search strategy of All Databases in Appendix | X | X | ||

| Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) undertaking reviews in Health Care | 2009 | X | X | X | X | Full search strategy with minimum of editing | journals | ||

| PRISMA Statement: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses | 2009 | X | X | X | X | Full Search Strategy of at least 1 Database | X | X | |

| Campbell Collaboration Systematic Review Guide | 2010 | X | X | X | Full search strategies for each database | X | grey literature sources | ||

| Institute of Medicine (IOM) Standards for Systematic Reviews | 2011 | X | Web Browser | X | X | Line-by-line description | X | X | |

Table 3.

Core standards common among the 10 checklists

| Search Topic | Item No. |

Description |

|---|---|---|

| Databases | ||

| 1 | Provide a list of all databases searched in the Methods section. | |

| Name of Interface (Host or Platform) | ||

| 2 | Provide the platform, host and/or vendor used to access the database searched. Cite each database and platform in the reference list. | |

| Years Covered by the Search | ||

| 3 | Clearly define the start and end date of each search implemented in each of the databases. | |

| Date the Last Search was Performed | ||

| 4 | Provide the last date the search was run in each database searched. | |

| Complete Search Strategy | ||

| 5 | At the time of publication, Provide the full search for each database exactly as it was run on the platform in an appendix or web extra. The strategy should be copied and pasted exactly as run. Search must be repeatable. | |

| Search Limits | ||

| 6 | List any search limits that were applied to the search including: language limits, publication type limits, human, publication status restrictions, or any other limits. | |

| Supplemental Search | ||

| Types of Supplemental Search | 7 | (1) check reference list of included studies; (2) Search specialized registries, websites, conference abstracts, Internet or grey literature for unpublished literature; (3) Contact individuals, experts, or organizations; (4) Hand search of journals (list all journals and time period). |

| Qualification of Searcher | ||

| 8 | Acknowledge in the methods section the inclusion or consultation of an individual with experience developing and implementing comprehensive systematic searches. | |

Table 4.

Journals Publishing Systematic Reviews

| Year of Publication - Cochrane Reviews (n=9) | n(%) | |

|

| ||

| 2000 – 2005 | 3 (33%) | |

| 2006 – 2010 | 6 (66%) | |

| Year of Publication - Non-Cochrane Reviews (n=93) | n(%) | |

|

| ||

| 2000 – 2005 | 36 (39%) | |

| 2006 – 2010 | 57 (61%) | |

| Year of Publication - All Reviews (n=102) | n(%) | |

|

| ||

| 2000 – 2005 | 39 (38%) | |

| 2006 – 2010 | 63 (61%) | |

| Number of Journals Publishing Reviews* (n=51) | n(%) | |

|

| ||

| One or Two Reviews | 43 (84%) | |

| Three to Five Reviews | 4 (8%) | |

| Six to Eight | 0 | |

| Nine or More Reviews | 4 (8%) | |

51 Journals published the 102 reviews

1. How many studies reported the databases searched?

All guidelines concur that reviews must provide the name of each of the databases searched in the systematic review process and that reviews should not omit databases or give vague or generalized statements for databases searched (Table 2) (Booth 2006; Centre for Reviews and Dissemination 2009; Hammerstrom et al. 2010; Health Technology Assessment 2007; Institute of Medicine (IOM) 2011; Lefebvre et al. 2008; Moher et al. 1999; Moher et al. 2009; Shea et al. 2007; Stroup et al. 2000). The majority, 96 (94% of the reviews) provided the databases searched (see Table 5). Only a few reviews did not provide the databases searched, but made references to searching databases without actually naming those databases. The methods sections for these reviews referenced the databases with nonspecific labels such as “computerized databases were searched” or listed databases “e.g.” or “for example”. Other reviews made vague statements about reporting all the available literature without providing specifics on the search. All nine Cochrane reviews provided the databases searched.

Table 5.

Transparent Reporting of the Essential Search Elements

| Q. | Search Reporting Questions | Cochrane Reviews (n=9)a |

Non-Cochrane Reviews (n=93)b |

All Reviews (n=102) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n(%) | n(%) | n(%) | ||

| 1 | How many studies reported the databases searched? | 9 (100%) | 87 (94%) | 96 (94%) |

| 2 | How many reviews reported the interface (i.e. host, platform) used to access and search each database? | 0c | 8 (9%) | 8 (8%) |

| 3 | How many reviews clearly reported the time period of the searches? | 8 (89%) | 27 (29%) | 35 (34%) |

| 4 | How many reviews clearly reported the last date the search was implemented? | 7 (78%) | 11 (12%) | 18 (18%) |

| 5 | How many reviews reported the complete search of at least one or all databases in order to reproduce the search? | 6 (67%) | 7 (8%) | 13 (13%) |

| 6 | How many reviews provided the language limits? | 6 (67%) | 39 (42%) | 45 (44%) |

| 7 | How many reviews reported a supplemental search component? | 9 (100%) | 78 (84%) | 87 (85%) |

| 8 | How many reviews reported including an experienced searcher? | 1 (11%)d | 4 (4%) | 5 (5%) |

9 Cochrane Reviews are a subset of the 102 All Reviews

93 Non-Cochrane Reviews are a subset of the 102 All Reviews

"Name of the host" was a requirement of The Cochrane Handbook version 4.2.6 (2006). It was not a requirement in the 2008 version of The Cochrane Handbook 5.0.0 (2008)

Including an experienced searcher is not a requirement in The Cochrane Handbook

2. How many reviews reported the interface (i.e., host, platform) used to access and search each database?

Half of the 10 guidelines require naming the interface (e.g. OVID, PubMed, ProQuest, EBSCOhost, etc.) used to search a database. It is an important element in understanding how the search was actually conducted; to allow for both an evaluation and future updates (Booth 2006; Centre for Reviews and Dissemination 2009; Institute of Medicine (IOM) 2011; Moher et al. 2009; Stroup et al. 2000). Similar to selecting a search engine (e.g., Google, Yahoo, Bing) to explore the Internet, each search interface offers unique features that provide a different search experience, capabilities and results. For example, a search of the National Library of Medicine’s database MEDLINE is possible in PubMed or OVID. These two interfaces offer different ways to search text words which may garner different results (Katcher 2006; The Librarians' Searching Group 2013). As seen in Table 5, only 8 (8%) listed the interface, platform or provider for all the databases utilized (Coffin 2000; Lyles et al., 2007; Manhart and Holmes 2005; Paul-Ebhohimhen et al., 2008; Rees et al., 2004; Russak et al., 2005; Shepherd et al., 2010; Vijayakumar et al., 2006). None of the Cochrane reviews were among the reports with database interface reported. This reporting element was required in the 2006 Cochrane Handbook version 4.2.6 but was no longer required after the 2008 update in version 5.0.0 or subsequent editions since all Cochrane reviews are now required to provide the complete search as it appeared on the platform (Higgins et al. 2006b; Lefebvre et al. 2008).

3. How many reviews clearly reported the time period of the searches?

All 10 guidelines require a clear statement of the time period covered for the search as this is essential when looking to replace or update a systematic review (Table 2). Only 35 of all reviews (34%) clearly stated a start and end date for the search performed in online databases (Table 5). The percentage of the 9 Cochrane reviews (i.e., 89%) is higher than the 29% of non-Cochrane reviews that provided this information, but not even all the Cochrane reviews reported the time period covered. Some examples of not meeting the time period criteria include studies that stated “available by”, “published between” or available before” certain dates. These statements do not clearly define the period searched in the databases.

4. How many reviews clearly reported the last date the search was implemented?

The Cochrane Handbook (version 5.0.0) clearly states that the search methods should “note the dates of the last search for each database and the period searched” (Lefebvre et al. 2008). As seen in Table 2, reporting the last date the search was run became a requirement of the Cochrane Handbook in 2008, and has been included in all guidelines that followed (Centre for Reviews and Dissemination 2009; Institute of Medicine (IOM) 2011; Lefebvre et al. 2008; Moher et al., 2011). Only 18 reviews (18%) reported this information. Cochrane reviews did better reporting this element (78%) than non-Cochrane reviews (12%), but not all Cochrane reviews reported this component (Table 5).

5. How many reviews reported the complete search of at least one or all databases in order to reproduce the search in the paper at the time of publication?

Nine of the 10 guidelines provided instruction on reporting complete search strategies. Only 13 reviews (13%) provided the complete search as it appeared on the platform for at least one or more databases (Table 5). More Cochrane reviews (67%) than non-Cochrane reviews 8% provided this information. The majority of the reviews (87%) made no mention of the actual search, referenced terms in a “for example framework”, or referenced the subject areas without divulging the actual search terms included. Some of the reviews only referred to incorporating text words with ambiguous statement such as “uniterm combinations”, or “search terms” without clearly explaining if the terms were searched as text words, index terms or both.

A further examination of full search reporting (Table 6) shows that seven reviews including four Cochrane reviews and three non-Cochrane reviews provided the full search implemented in every database for the review (Bateganya et al., 2010; Foss et al., 2007; Paul-Ebhohimhen et al. 2008; Rees et al. 2004; Sorsdahl et al., 2009; Underhill et al., 2007a; Underhill et al., 2008). There were six reviews that presented the complete search for one database which includes two Cochrane reviews (Elwy et al., 2002; Meader et al., 2010; Shahmanesh et al., 2008; Shepherd et al. 2010; Underhill et al., 2007b; Vidanapathirana et al., 2005).

Table 6.

Provide a complete and reproducible search

| Description of the Search | Cochrane Reviews (n=9)a |

Non-Cochrane Reviews (n=93)b |

All Reviews (n=102) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000– 2005 (n=3) |

2006– 2010 (n=6) |

n(%) | 2000– 2005 (n=36) |

2006– 2010 (n=57) |

n(%) | 2000– 2005 (n=39) |

2006– 2010 (n=63) |

n(%) | |

| Cochrane Standard: Full search for all the databases searched as it appeared on each platform | 0 | 4 | 4 (44%) | 1 | 2 | 3 (3%) | 1 | 6 | 7 (7%) |

| Full Search for one database as it appeared on the platformc | 1 | 1 | 2 (22%) | 1 | 3 | 4 (4%) | 2 | 4 | 6 (6%) |

| Mentioned using Index Terms and text words, but did not provide themd | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 7 | 11 (12%) | 4 | 7 | 11 (11%) |

| Provided some text words, "uniterm combinations" or search termsd | 2 | 1 | 3 (33%) | 13 | 23 | 36 (39%) | 15 | 24 | 39 (38%) |

| Provided no index or text wordsd | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 22 | 39 (41%) | 17 | 22 | 39 (38%) |

9 Cochrane Reviews are a subset of the 102 reviews

93 Non-Cochrane Reviews are a subset of the 102 reviews

Provided a reproducible search

Did not provide a reproducible search

The well reported reviews were published in journals that had instructions to follow a systematic review reporting standard. The 13 reviews that did provide the full search of one or all databases were in publications that required the following: the Cochrane Handbook, EPPI-Centre final report guidance, Health Technology Assessment (HTA) checklist, or the PRISMA guideline.

6. How many reviews reported which languages were included?

Eight of the 10 guidelines require reporting the inclusion or exclusion of studies based on language at either the search level (QUOROM, STARLITE, HTA, Cochrane, and Campbell) or at the screening phase (AMSTAR, PRISMA, and MOOSE) (Table 2). A little less than half of the reviews, 45 (44%), referenced language limitations within the paper and the remaining 57 reviews (56%) did not provide any description of the language restrictions (Table 5). Two third of the 9 Cochrane reviews provided this required information, compared to 42% non-Cochrane reviews.

7. How many reviews reported a supplemental search component?

Nine of the 10 guidelines describe supplemental searching as any combination of methods including: checking reference lists, searching specialized registries/databases/websites, hand searching journals and contacting authors (Table 2). The majority of the reviews, 87 (85%) reported at least one specific method of supplemental search. All the Cochrane reviews and 84% non-Cochrane reviews reported on the supplemental search component.

8. How many reviews included an experienced searcher?

Two of the 10 guidelines recommend reporting the qualifications of the searcher (Table 2). A skilled searcher possesses an understanding of journal indexing, database architecture, and knowledge of the various specialized registries available to locate ongoing research (Zhang et al., 2006). Only 5 (5%) reviews mentioned consulting or including an experienced searcher in the development and implementation of the search (Berg 2009; Herbst et al., 2007a; Hogben et al., 2007; Shepherd et al. 2010; Vidanapathirana et al. 2005) (Table 5). Although it is not a requirement of the Cochrane Handbook only one of the 9 Cochrane reviews (11%) reported this information (Vidanapathirana et al. 2005). Only four non-Cochrane reviews (4%) provided this information.

Discussion

We identified eight common reporting elements across the guidelines with search reporting instructions and found that some search elements are more likely to be reported than the others. The majority of the reviews are fully reporting on two elements: the databases searched as well as the supplemental search. Less complete reporting was noted on the remaining six elements: describing the interface used to search each database, the years included in the electronic search, a complete search strategy for at least one or more of the databases, the language limitations applied, and consulting or including an experienced searcher. Taken as a whole, our findings point out that there is considerable room for improvement in the reporting of search methods in HIV behavioral interventions.

One component that is required by a majority of the guidelines, but a low percentage of reviews provided the information is reporting search strategy (question 5). This finding is consistent with previous assessments of systematic review search protocols in other subject domains and health topics (Fehrmann and Thomas 2011; Golder et al., 2008; Sampson and McGowan 2006; Yoshii et al., 2009). The lack of complete reporting of the search strategy threatens the quality of research synthesis by not allowing for an adequate peer review or examination of the methods used to gather the evidence and limits replicating searches for future update. One related question is “what constitutes sharing the full search”. Ten reporting guidelines have a varying degree of expectations when it comes to sharing the search. The earlier reporting checklists made requests to provide search strategy without specifically outlining how the search should be presented with qualifiers such as “sample”, “if feasible” or “upon request” (Booth 2006; Health Technology Assessment 2007; Shea et al. 2007; Stroup et al. 2000). The more recent guidelines like the Cochrane Handbook, Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD), and Campbell Collaboration all require the complete search as it appeared on the platform with a minimum of editing, preferably with the number of articles identified (Centre for Reviews and Dissemination 2009; Hammerstrom et al. 2010; Lefebvre et al. 2008). PRISMA guidance requires to “present full electronic search strategy for at least one database, including any limits used, such that it could be repeated” and the 2008 edition of the Cochrane Handbook (Version 5.0.0) requests the full search for each database as the search appeared on the platform to be included in the appendix of the review (Lefebvre et al. 2008).

There is no doubt that improving the completeness of reporting search strategies requires journals and authors to make the information available to the readers. Chalmers and Haynes (1994) proposed publishing a more detailed report electronically to supplement an abbreviated synopsis of the search in the printed edition of a review (Chalmers and Haynes 1994). The PRISMA checklist companion piece publication by Liberati et al. expands upon the requirement for the full search of one database and “strongly encourages” journals to make all the searches available through a “Web extra,” appendix, or electronic link to an archive, to make search strategies accessible to readers” when the space is limited (Liberati et al. 2009). The HTA Reports suggests making the full search available on request. Eight of the 89 reviews that did not provide the full search strategy but made statements that the full search strategy were available from the author upon request (Burton et al., 2010; Darbes et al., 2008; Herbst et al., 2005; Herbst et al., 2007b; McCoy et al., 2010; Padian et al., 2010; Trelle et al., 2007; Wright and Walker 2006). After requesting the full search strategy from all eight authors, seven responded with the full search. Although we had a high return when requesting searches from the authors there is always a chance that the data will not be available since it was not published. Making statements that a thorough search was conducted without actually providing enough details of the search at the time of publication should be avoided. The goal should be to provide complete transparency at the time of publication, not upon request. Our findings suggest that the well reported reviews were published in journals that had a more explicit request to follow a systematic review reporting standard. We strongly recommend journals provide the space for all search information to accompany the report, as a web extra, or an appendix rather than having the readers contact the authors for search strategies.

Another component that is recommended by half of the guidelines but has a low percentage of reporting is interface (i.e., host, platform) used to search each of the databases (question 2). Search capabilities vary greatly by interface, and influence the way a database is searched. For instance, the databases MEDLINE and PubMed are often stated interchangeably; however, MEDLINE is a major database available within PubMed interface, but PubMed is also a database beyond MEDLINE (Jankowski 2008; National Library of Medicine 2011). MEDLINE can be searched through various interfaces garnering different results. In addition, some interfaces allow searching multiple databases at one time. Aggregators usually require a common search language in order to search more than one database which could impact the search results. Ultimately, a search cannot be truly replicated without knowledge of the interface employed to search the database. We recommend more reporting on this important element. We also recommend the inclusion of the language limitation in the report of the searches performed since it is required by the majority of the guidelines.

Another important element to report but few reviews reported the information is the qualification of the searcher (question 8). In 2003, the MLA policy statement on the role of the expert searchers in health science libraries emphasized including librarians in the research process (Medical Library Association 2011). The MLA has been promoting the education of librarians as expert searchers with the 2008 publication of the MLA’s Essential Guide to Becoming an Expert Searcher (Jankowski 2008; Medical Library Association 2011). Searcher credentials are not a requirement of the PRISMA checklist, although the MOOSE checklist does request the qualifications of the searchers to be reported in the review (Moher et al. 2009; Stroup et al. 2000). An expert searcher is an individual that possesses the knowledge as well as the skill to implement the techniques and strategies necessary to locating information. It is a skill that comes with experience and practice. It is not easily quantifiable, but it is an individual with experience developing and implementing complex searches (Jankowski 2008; Sampson et al., 2008b). Recent publications from the Institute of Medicine and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality have stated the necessity to include a librarian or expert searcher in the formulation of a systematic search strategy. The AHRQ’s report on finding evidence for comparing medical interventions emphasizes the inclusion of information professionals in systematic reviews often translates into better reporting of the search strategy within the review (Institute of Medicine (IOM) 2011; Relevo and Balshem 2011). The systematic search strategy is a complicated practice that requires the knowledge and experience to develop, test, and implement complex searches (European Centre for Disease Control and Prevention 2011). A systematic review team can be substantially benefitted from a skilled and experienced searcher who understands journal indexing, database architecture, and knowledge of the various specialized registries available to locate ongoing research (McGowan and Sampson 2005; Zhang et al. 2006). Additionally, an experienced searcher will be well versed in the documentation and description of the search at the time of publication and should be considered for acknowledgement or as an author if they meet the journal standards for publication. Given all the benefits, we recommend including an individual with systematic search skills and experience or at least consulting this type of individual before conducting the search and making this information available in the methods (Sampson et al. 2008b).

We also see a moderate association between the number of guidelines that recommend a specific reporting elements and the percentage of the reviews providing the information on the element (e.g. naming databases searched, indicating supplemental searches were conducted). As noticed in the result, the 13 reviews that did provide the full search of one or all databases were in publications that required following the Cochrane handbook, EPPI-Centre final report guidance, HTA checklist or the PRISMA guideline. It is encouraging as the findings suggest that reporting guidelines do affect the quality of reporting. However, previous publications showed that few guidelines are enforced by a journal or its reviewers to critically assess the reporting within systematic reviews (Vandenbroucke 2009). Recently the Institute of Medicine (IOM) published Finding What Works in Health Care: Standards for Systematic Reviews as an in-depth analysis of the systematic review process, and as guidance for the reporting of systematic review findings. IOM concluded that no systematic review standards are consistently followed or implemented (Institute of Medicine (IOM) 2011). When we examined the publisher “instruction to authors” for the eight reviews that were published in 2010 but did not provide the full search of at least one database, we found only three publishers required following the PRISMA checklist and the other five did not require adherence to a systematic review reporting tool. This finding highlights the necessity for publishers to not only require a reporting guideline but also to use the tool as a checklist to verify completeness in the acceptance process. The Cochrane Handbook version 5.1.0 (Chapter 6.6.1 Documenting the search process) recommends a sign-off practice that could greatly improve search reporting (Lefebvre et al., 2011). We recommend journals and publishers should consider the sign-off practice by the Cochrane Collaboration for improving search reporting. Additionally, the Cochrane Collaboration published “Methodological standards for the reporting of the new Cochrane Intervention Reviews (1.1)” (Chandler et al., 2012a). This document exemplifies best practices for reporting reviews and is a helpful guide, in combination with the Cochrane publication, “Methodological standards for the conduct of new Cochrane Intervention Reviews (2.2)” (Chandler et al., 2012b), for those who are conducting systematic reviews.

Conclusion

Our review of HIV behavioral intervention literature and previous reviews of the reporting quality of systematic review in other disciplines illustrates the necessity to improve search reporting in systematic reviews (Fehrmann and Thomas 2011; Golder et al. 2008; Sampson et al. 2008b; Simera et al., 2010; Yoshii et al. 2009). The reporting elements we examined and issues we discussed here are fundamental to search reporting within all systematic reviews regardless of the area of study as the reporting elements are convergent from 10 commonly known reporting guidelines. We encourage other fields to promote the completeness of search reporting and to conduct similar evaluations to assess and monitor the progress of search method reporting.

We recommend authors adopt complete and transparent reporting of their search methods as laid out in the 10 guidelines included in this review. We also encourage journal editors to verify the complete reporting of the search method as part of the peer review process (McGowan et al., 2010) and acceptance to publication and provide a web extra or online appendix for the search methods of all systematic reviews. The improvement of reporting quality depends on the authors, reviewers and journal editors. Through adopting and enforcing reporting guidelines, we can ensure transparency and future replication of the reviews will further facilitate the research synthesis and evidence-based recommendation.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- Auerbach JD, Hayes RJ, Kandathil SM. Overview of effective and promising interventions to prevent HIV infection. World Health Organization Technical Report Series. 2006;938:43–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateganya MH, Abdulwadud OA, Kiene SM. Home-based HIV voluntary counseling and testing in developing countries. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007;(4):CD006493. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006493.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateganya MH, Abdulwadud OA, Kiene SM. Home-based HIV voluntary counseling and testing (vct) for improving uptake of testing. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010;(7):CD006493. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006493.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg R. The effectiveness of behavioural and psychosocial HIV/STI prevention interventions for MSM in Europe: a systematic review. Euro Surveillance. 2009;14(48):pii: 19430. doi: 10.2807/ese.14.48.19430-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BMJ Evidence Based Centre. Clinical evidence: study design search filters. 2012 Available at: http://clinicalevidence.bmj.com/x/set/static/ebm/learn/665076.html.

- Booth A. "Brimful of STARLITE": toward standards for reporting literature searches. Journal of the Medical Library Association. 2006;94(4):421–429. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boynton J, Glanville J, McDaid D, Lefebvre C. Identifying systematic reviews in MEDLINE: developing an objective approach to search strategy design. Journal of Information Science. 1998;24(3):137–157. [Google Scholar]

- Burton J, Darbes LA, Operario D. Couples-focused behavioral interventions for prevention of HIV: systematic review of the state of evidence. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14(1):1–10. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9471-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Undertaking Systematic Reviews of Research on Effectiveness: CRD's guidance for those carrying out or commissioning reviews. (2) 2001 Report Number 4. [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Systematic Reviews: CRD's Guidance for Undertaking Reviews in Health Care. 2009 Available at: http://www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/pdf/Systematic_Reviews.pdf.

- Chalmers I, Haynes B. Reporting, updating, and correcting systematic reviews of the effects of health care. British Medical Journal. 1994;309(6958):862–865. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6958.862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler J, Churchill R, Higgins J, Lasserson T, Tovey D. Methodogical standards for the reporting of new Cochrane Intervention Reviews Version 1.1 (17 December 2012) 2012a Available at: http://www.editorial-unit.cochrane.org/sites/editorial-unit.cochrane.org/files/uploads/MECIR%20Reporting%20standards%201.1_17122012_1.pdf.

- Chandler J, Churchill R, Higgins J, Lasserson T, Tovey D. Methodological standards for the conduct of new Cochrane Intervention Reviews Version 2.2 (17 December 2012) 2012b Available at: http://www.editorial-unit.cochrane.org/sites/editorial-unit.cochrane.org/files/uploads/MECIR_conduct_standards%202.2%2017122012.pdf.

- Chen P. Measures needed to strengthen strategic HIV/AIDS prevention programmes in China. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health. 2007;19(1):3–7. doi: 10.1177/10105395070190010201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffin P. Syringe availability as HIV prevention: a review of modalities. Journal of Urban Health. 2000;77(3):306–330. doi: 10.1007/BF02386743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Counsell C. Formulating questions and locating primary studies for inclusion in systematic reviews. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1997;127(5):380–387. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-5-199709010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CSA ProQuest-Sociological Abstracts [database online] Ann Arbor, MI: PROQUEST; 2005. [Accessed May 2010; Updated May 2011]. [Google Scholar]

- Darbes L, Crepaz N, Lyles C, Kennedy G, Rutherford G. The efficacy of behavioral interventions in reducing HIV risk behaviors and incident sexually transmitted diseases in heterosexual African Americans. AIDS. 2008;22(10):1177–1194. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282ff624e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLuca JB, Mullins MM, Lyles CM, Crepaz N, Kay L, Thadiparthi S. Developing a comprehensive search strategy for evidence-based systematic review. Evidence Based Library and Information Practice. 2008;3(1):3–32. [Google Scholar]

- DesJarlais DC, Semaan S. Interventions to reduce the sexual risk behaviour of injecting drug users. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2005;16(Supplement 1):S58–S66. [Google Scholar]

- EBSCOhost-CINAHL [database online] Ipswich, MA: EBSCO Publishers; 1981. [Accessed May 2010; Updated May 2011]]. [Google Scholar]

- Elwy AR, Hart GJ, Hawkes S, Petticrew M. Effectiveness of interventions to prevent sexually transmitted infections and human immunodeficiency virus in heterosexual men: a systematic review. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2002;162(16):1818–1830. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.16.1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EQUATOR Network. 2011 Available at: http://www.equator-network.org/

- European Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. Evidence-based methodologies for public health - How to assess the best available evidence when time is limited and there is a lack of sound evidence. 2011 Available at: http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/1109_TER_evidence_based_methods_for_public_health.pdf.

- Fehrmann P, Thomas J. Comprehensive computer searches and reporting in systematic reviews. Research Synthesis Methods. 2011;2(1):15–32. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JD, Smith L. Secondary prevention of HIV infection: the current state of prevention for positives. Current Opinion in HIV and AIDS. 2009;4(4):279–287. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32832c7ce5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foss AM, Hossain M, Vickerman PT, Watts CH. A systematic review of published evidence on intervention impact on condom use in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2007;83(7):510–516. doi: 10.1136/sti.2007.027144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golder S, Loke Y, McIntosh HM. Poor reporting and inadequate searches were apparent in systematic reviews of adverse effects. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2008;61(5):440–448. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hailey D. Toward transparency in health technology assessment: a checklist for HTA reports. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care. 2003;19(1):1–7. doi: 10.1017/s0266462303000011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammerstrom K, Wade A, Jorgensen A-MK. Searching for studies: a guide for information retrieval for Campbell Systematic Reviews. Campbell Systematic Reviews 2010: Supplement 1. 2010 doi: 10.4073/csrs.2010.1. Available at: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes RB, Wilczynski N, McKibbon KA, Walker CJ, Sinclair JC. Developing optimal search strategies for detecting clinically sound studies in MEDLINE. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 1994;1(6):447–458. doi: 10.1136/jamia.1994.95153434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Technology Assessment. A Checklist for HTA Reports (updated 2007) 2007 Available at: http://www.inahta.org/HTA/Checklist/

- Hemingway P, Brereton N. What is a systematic review? 2001 Available at: http://www.medicine.ox.ac.uk/bandolier/painres/download/whatis/syst-review.pdf.

- Herbst JH, Beeker C, Mathew A, McNally T, Passin WF, Kay LS, Crepaz N, Lyles CM, Briss P, Chattopadhyay S, Johnson RL. The effectiveness of individual-, group-, and community-level HIV behavioral risk-reduction interventions for adult men who have sex with men. A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007a;32(Supplement 4):38–67. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbst JH, Kay LS, Passin WF, Lyles CM, Crepaz N, Marin BV HIV/AIDS Prevention Research Synthesis (PRS) Team. A systematic review and meta-analysis of behavioral interventions to reduce HIV risk behaviors of Hispanics in the United States and Puerto Rico. AIDS and Behavior. 2007b;11(1):25–47. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9151-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbst JH, Sherba RT, Crepaz N, DeLuca JB, Zohrabyan L, Stall RD, Lyles CM HIV/AIDS Prevention Research Synthesis Team. A meta-analytic review of HIV behavioral interventions for reducing sexual risk behavior of men who have sex with men. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2005;39(2):228–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbst JH Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Recommendations for use of behavioral interventions to reduce the risk of sexual transmission of HIV among men who have sex with men. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;32(Supplement 4):S36–S37. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 4.2.6 [updated September 2006] 2006a Available at: http://www.cochrane.org/training/cochrane-handbook.

- Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Locating and selecting studies. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 4.2.6 (updated September 2006); Section 5. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2006. 2006b Available at: http://www.cochrane.org/training/cochrane-handbook.

- Hoffmann O, Boler T, Dick B. Achieving the global goals on HIV among young people most at risk in developing countries: young sex workers, injecting drug users and men who have sex with men. World Health Organization Technical Report Series. 2006;938:287–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogben M, McNally T, McPheeters M, Hutchinson AB. The effectiveness of HIV partner counseling and referral services in increasing identification of HIV-positive individuals a systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;33(2 Supplement 1):S89–S100. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (IOM) Finding What Works in Health Care: Standards for Systematic Reviews. The National Academies Press; Washington, D.C.: 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jankowski TA. Essential Guide to Becoming an Expert Searcher: Proven Techniques, Strategies, and Tips to Finding Information. Neal -Schuman Publishers, Inc; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Katcher B. MEDLINE: A Guide to Effective Searching in PubMed and Other Interfaces. 2. Ashbury Press; San Francisco, CA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre C, Manheimer E, Glanville J Chapter 6: Searching for studies. Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.0.0 (updated February 2008) The Cochrane Collaboration, 2008. 2008 Available at: http://www.cochrane.org/training/cochrane-handbook.

- Lefebvre C, Manheimer E, Glanville J Chapter 6: Searching for studies. Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.0.2 (updated September 2009) The Cochrane Collaboration, 2009. 2009 Available at: http://www.cochrane.org/training/cochrane-handbook.

- Lefebvre C, Manheimer E, Glanville J Chapter 6: Searching for studies. Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011) The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. 2011 Available at: http://www.cochrane.org/training/cochrane-handbook.

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2009;62(10):e1–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyles CM, Kay LS, Crepaz N, Herbst JH, Passin WF, Kim AS, Rama SM, Thadiparthi S, DeLuca JB, Mullins MM HIV/AIDS Prevention Research Synthesis Team. Best-evidence interventions: findings from a systematic review of HIV behavioral interventions for US populations at high risk, 2000–2004. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97(1):133–143. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.076182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manhart LE, Holmes KK. Randomized controlled trials of individual-level, population-level, and multilevel interventions for preventing sexually transmitted infections: what has worked? Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2005;191(Supplement 1):S7–S24. doi: 10.1086/425275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy SI, Kangwende RA, Padian NS. Behavior change interventions to prevent HIV infection among women living in low and middle income countries: a systematic review. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14(3):469–482. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9644-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan J, Sampson M, Lefebvre C. An evidence based checklist for the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS EBC) Evidence Based Library and Information Practice. 2010;5(1):149–153. [Google Scholar]

- Meader N, Li R, Des J, Pilling S. Psychosocial interventions for reducing injection and sexual risk behaviour for preventing HIV in drug users. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010;(1):CD007192. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007192.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medical Library Association. Medical Library Association Policy Statement: Role of Expert Searching in Health Science Libraries. 2011 Available at: http://www.mlanet.org/resources/expert_search/policy_expert_search.html. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Moher D, Altman DG, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J. PRISMA statement. Epidemiology. 2011;22(1):128. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181fe7825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Cook DJ, Eastwood S, Olkin I, Rennie D, Stroup DF. Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: the QUOROM statement. Quality of Reporting of Meta-analyses. Lancet. 1999;354(9193):1896–1900. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)04149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2009;151(4):264–269. W64. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Library of Medicine. Fact sheet: what's the difference between MEDLINE and PubMed? 2011 Available at: http://www.nlm.nih.gov/pubs/factsheets/dif_med_pub.html.

- Niederstadt C, Droste S. Reporting and presenting information retrieval processes: the need for optimizing common practice in health technology assessment. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care. 2010;26(4):450–457. doi: 10.1017/S0266462310001066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OVID-EMBASE [database online] New York, NY: Wolters, Kluwer; 1988. [Accessed May 2010; Updated May 2011]. [Google Scholar]

- OVID-MEDLINE [database online] New York, NY: Wolters Kluwer; 1988. [Accessed May 2010; Updated May 2011]. [Google Scholar]

- OVID-PsycINFO [database online] New York, NY: Wolters Kluwer; 1988. [Accessed May 2010; Updated May 2011]. [Google Scholar]

- Padian NS, McCoy SI, Balkus JE, Wasserheit JN. Weighing the gold in the gold standard: challenges in HIV prevention research. AIDS. 2010;24(5):621–635. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328337798a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick TB, Demiris G, Folk LC, Moxley DE, Mitchell JA, Tao D. Evidence-based retrieval in evidence-based medicine. Journal of the Medical Library Association. 2004;92(2):196–199. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul-Ebhohimhen VA, Poobalan A, van Teijlingen ER. A systematic review of school-based sexual health interventions to prevent STI/HIV in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees R, Kavanagh J, Burchett H, Shepherd J, Brunton G, Harden A, Thomas J, Oliver S, Oakley A. HIV health promotion and men who have sex with men (MSM): a systematic review of research relevant to the development and implementation of effective and appropriate interventions. Eppi Centre; London: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Relevo R, Balshem H. Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. Rockville, MD: 2011. Finding Evidence for Comparing Medical Interventions; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ross DA. Behavioural interventions to reduce HIV risk: what works? AIDS. 2010;24(Supplement 4):S4–S14. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000390703.35642.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russak SM, Ortiz DJ, Galvan FH, Bing EG. Protecting our militaries: a systematic literature review of military human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome prevention programs worldwide. Military Medicine. 2005;170(10):886–897. doi: 10.7205/milmed.170.10.886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson M, McGowan J. Errors in search strategies were identified by type and frequency. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2006;59(10):1057–1063. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson M, McGowan J, Cogo E, Grimshaw J, Moher D, Lefebvre C. An evidence-based practice guideline for the peer review of electronic search strategies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2009;62(9):944–952. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson M, McGowan J, Lefebvre C, Moher D, Grimshaw J. PRESS: Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies. Ottawa: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2008a. Available at: http://www.cadth.ca/media/pdf/477_PRESS-Peer-Review-Electronic-Search-Strategies_tr_e.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson M, McGowan J, Tetzlaff J, Cogo E, Moher D. No consensus exists on search reporting methods for systematic reviews. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2008b;61(8):748–754. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahmanesh M, Patel V, Mabey D, Cowan F. Effectiveness of interventions for the prevention of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections in female sex workers in resource poor setting: a systematic review. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 2008;13(5):659–679. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea B, Dube C, Moher D. Assessing the quality of reports of systematic reviews: the QUOROM statement compared to other tools. In: Egger M, Smith GD, Altman DG, editors. Systematic Reviews in Health Care: Meta-Analysis in Context. BMJ Books; London: 2001. pp. 122–139. [Google Scholar]

- Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, Boers M, Andersson N, Hamel C, Porter AC, Tugwell P, Moher D, Bouter LM. Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2007;7:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-7-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd J, Kavanagh J, Picot J, Cooper K, Harden A, Barnett-Page E, Jones J, Clegg A, Hartwell D, Frampton GK, Price A. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of behavioural interventions for the prevention of sexually transmitted infections in young people aged 13–19: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technology Assessment. 2010;14(7):iii–iv. doi: 10.3310/hta14070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simera I, Moher D, Hoey J, Schulz KF, Altman DG. A catalogue of reporting guidelines for health research. European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2010;40(1):35–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2009.02234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorsdahl K, Ipser JC, Stein DJ. Interventions for educating traditional healers about STD and HIV medicine. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009;(4):CD007190. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007190.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takacs IG, Demetrovics Z. The efficacy of needle exchange programs in the prevention of HIV and hepatitis infection among injecting drug users. [Hungarian] Psychiatria Hungarica. 2009;24(4):264–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Cochrane Library. Issue 5. Chichester: Wiley; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- The Cochrane Library. Issue 5. Chichester: Wiley; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- The InterTASC Information Specialists' Sub-Group. Search filter resource. 2012 Available at: http://www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/intertasc/

- The Librarians' Searching Group. Things to keep in mind when search MEDLINE. 2013 Available at: http://www.nyam.org/fellows-members/ebhc/eb_medline2.html.

- Trelle S, Shang A, Nartey L, Cassell JA, Low N. Improved effectiveness of partner notification for patients with sexually transmitted infections: systematic review. British Medical Journal. 2007;334(7589):354. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39079.460741.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underhill K, Montgomery P, Operario D. Abstinence-plus programs for HIV infection prevention in high-income countries. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2008;(1):CD007006. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underhill K, Operario D, Montgomery P. Abstinence-only programs for HIV infection prevention in high-income countries. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007a;(4):CD005421. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005421.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underhill K, Operario D, Montgomery P. Systematic review of abstinence-plus HIV prevention programs in high-income countries. PLoS Med. 2007b;4(9):e275. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenbroucke JP. STREGA, STROBE, STARD, SQUIRE, MOOSE, PRISMA, GNOSIS, TREND, ORION, COREQ, QUOROM, REMARK… and CONSORT: for whom does the guideline toll? Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2009;62(6):594–596. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidanapathirana J, Abramson MJ, Forbes A, Fairley C. Mass media interventions for promoting HIV testing. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2005;(3):CD004775. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004775.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayakumar G, Mabude Z, Smit J, Beksinska M, Lurie M. A review of female-condom effectiveness: patterns of use and impact on protected sex acts and STI incidence. International Journal of STD and AIDS. 2006;17(10):652–659. doi: 10.1258/095646206780071036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White VJ, Glanville JM, Lefebvre C, Sheldon TA. A statistical approach to designing search filters to find systematic reviews: objectivity enhances accuracy. Journal of Information Science. 2001;27(6):357–370. [Google Scholar]

- Wright NM, Walker J. Homelessness and drug use -- a narrative systematic review of interventions to promote sexual health. AIDS Care. 2006;18(5):467–478. doi: 10.1080/09540120500220474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshii A, Plaut DA, McGraw KA, Anderson MJ, Wellik KE. Analysis of the reporting of search strategies in Cochrane systematic reviews. Journal of the Medical Library Association. 2009;97(1):21–29. doi: 10.3163/1536-5050.97.1.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Sampson M, McGowan J. Reporting of the role of the expert searcher in Cochrane reviews. Evidence Based Library and Information Practice. 2006;1(4):3–16. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.