Abstract

BACKGROUND

Intradialytic hypertension occurs in 5–20% of hemodialysis treatments. Observational data support an association between intradialytic hypertension and long-term mortality. However, the short-term consequences of recurrent intradialytic hypertension are unknown.

METHODS

Data were taken from a cohort of prevalent hemodialysis patients receiving treatment at a large United States dialysis organization on 1 January 2010. A retrospective cohort design with a 180-day baseline, 30-day exposure assessment, and 30-day follow-up period was used to estimate the associations between intradialytic hypertension frequency and 30-day outcomes. Intradialytic hypertension frequency was defined as the proportion of exposure period hemodialysis treatments with a predialysis to postdialysis systolic blood pressure rise >0 mm Hg. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression, adjusted for baseline clinical, laboratory, and dialysis treatment covariates, was used to estimate hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals.

RESULTS

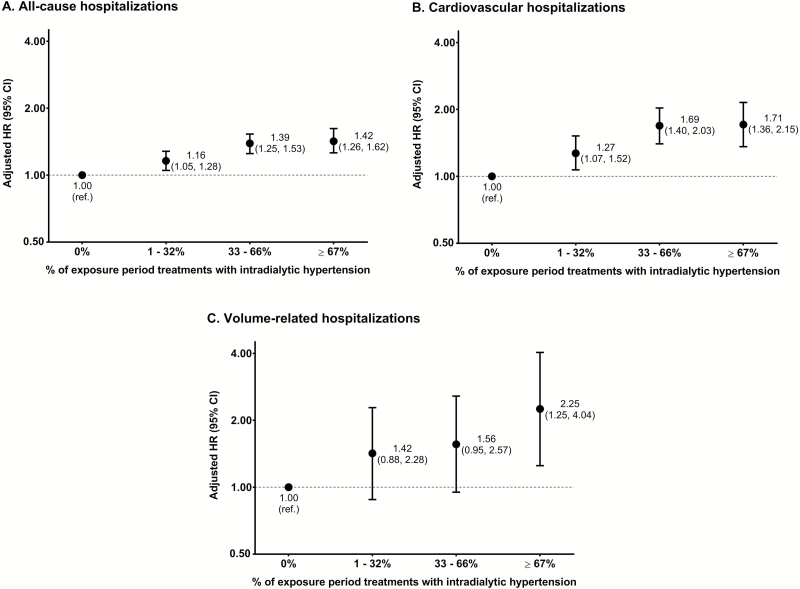

Of the 37,094 study patients, 5,242 (14.1%), 17,965 (48.4%), 10,821 (29.2%), 3,066 (8.3%) had intradialytic hypertension in 0%, 1–32%, 33–66%, and ≥67% of exposure period treatments, respectively. More frequent intradialytic hypertension was associated with incremental increases in 30-day mortality and hospitalizations. Patients with intradialytic hypertension in ≥67% (vs. 0%) of exposure period treatments had the highest risk of all-cause death, hazard ratio [95% confidence interval]: 2.57 [1.68, 3.94]; cardiovascular (CV) death, 3.68 [1.89, 7.15]; all-cause hospitalizations, 1.42 [1.26, 1.62]; CV hospitalizations, 1.71 [1.36, 2.15]; and volume-related hospitalizations, 2.25 [1.25, 4.04].

CONCLUSIONS

Among prevalent hemodialysis patients, more frequent intradialytic hypertension was incrementally associated with increased 30-day morbidity and mortality. Intradialytic hypertension may be an important short-term risk marker in the hemodialysis population.

Keywords: blood pressure, hemodialysis, hospitalization, hypertension, intradialytic hypertension, mortality

Cardiovascular (CV) disease is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States end-stage renal disease (ESRD) population. Annually, approximately 30% of hospitalizations and 50% of deaths are attributed to CV causes.1 The etiology of CV disease among individuals receiving maintenance hemodialysis differs from that of the general population. Dialysis-specific risk factors such as repeated, large intradialytic fluid, and blood pressure (BP) shifts likely play substantial pathologic roles in dialysis-associated CV risk. Typical systolic BP behavior during hemodialysis is characterized by 2 phases, a relatively rapid BP decline in the first quarter of the treatment followed by a more gradual BP decline in the latter 75% of treatment.2 Deviations from the typical BP course such as intradialytic hypotension (a precipitous BP drop during hemodialysis) and intradialytic hypertension (a paradoxical predialysis to postdialysis BP rise also known as postdialysis hypertension) have been associated with increased morbidity and mortality.3–7 Of the 2 BP abnormalities, intradialytic hypertension has received comparatively less attention.

The occurrence of intradialytic hypertension is relatively common, impacting 5–20% of hemodialysis treatments.2,8,9 Observational data suggest that intradialytic hypertension may represent a modifiable risk factor among individuals receiving maintenance hemodialysis. A predialysis to postdialysis systolic BP rise (vs. decline) has been associated with increased long-term morbidity and mortality.6,7,10,11 While the exact pathophysiology is unclear, mechanistic studies suggest that volume overload contributes to a substantial proportion of intradialytic hypertension episodes.12,13 It is plausible that patients who experience intradialytic hypertension more frequently may be at increased risk for short-term hypervolemic repercussions such as flash pulmonary edema, and consequent hospitalizations and mortality. Thus, frequent intradialytic hypertension could be an important risk marker for short-term adverse events. To our knowledge, no prior studies have examined the associations between intradialytic hypertension frequency and short-term CV morbidity and mortality.

We undertook this study to investigate the association between intradialytic hypertension frequency and 30-day: (i) all-cause and CV mortality and (ii) all-cause, CV, and fluid-related hospitalizations in a large, nationally representative cohort of prevalent hemodialysis patients treated at a large dialysis organization in the United States.

METHODS

Study data, design, and population

We conducted an observational study in a point prevalent cohort of ESRD patients receiving in-center, thrice-weekly hemodialysis at a large, United States dialysis organization on 1 January 2010. The dialysis organization operates over 1,500 outpatient dialysis clinics throughout the nation. Its clinical database captures detailed demographic, clinical, laboratory, and dialysis treatment data. Laboratory data are measured on a biweekly or monthly basis. Hemodialysis treatment parameters, including predialysis and postdialysis BPs, are recorded on a treatment-to-treatment basis. The dialysis organization data were linked at the patient-level to the United States Renal Data System (USRDS), a national ESRD surveillance system. The USRDS data includes: the Medical Evidence Report Form (a patient history and registration form completed upon enrollment into the Medicare ESRD program), Medicare Enrollment database (a repository of Medicare beneficiary enrollment and entitlement data), ESRD Death Notification Form (the official form for reporting deaths), and Medicare standard analytic files (final action administrative claims data including Medicare Parts A, B and D).14

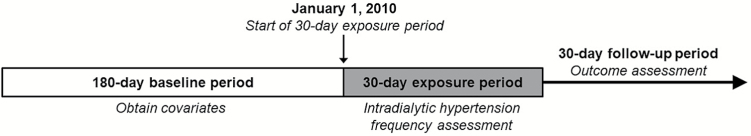

Figure 1 provides an overview of the study design. Briefly, we used a retrospective cohort design with a 180-day baseline period, 30-day exposure assessment period, and 30-day follow-up period to investigate the associations between intradialytic hypertension frequency and short-term clinical outcomes. Patients were included in this study if they: (i) were 18 years of age or older; (ii) had been on maintenance dialysis for at least 1 year; (iii) had at least 7 clinic-based hemodialysis treatments during the exposure period; and (iv) had Medicare Part A, B, and D coverage with Medicare as their primary payer during the baseline and exposure periods. Patients who received peritoneal or home hemodialysis during the baseline or exposure periods were excluded.

Figure 1.

Study design for primary analyses.

This study was approved by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Institutional Review Board (#15–2651). A waiver of consent was granted due to the study’s large cohort size, data anonymity, and retrospective nature.

Exposure assessment

A single dialysis treatment was considered complicated by intradialytic hypertension if there was a predialysis to postdialysis systolic BP rise (postdialysis systolic BP minus predialysis systolic BP >0 mm Hg).15 For each patient, the proportion of exposure period treatments affected by intradialytic hypertension was computed as: [(number of exposure period dialysis treatments with a change in systolic BP from predialysis to postdialysis >0 mm Hg)/(total number of dialysis treatments in the exposure period)] × 100%. Intradialytic hypertension frequency was parameterized as a multilevel categorical variable: 0%, 1–32%, 33–66%, and ≥67% of exposure period treatments with intradialytic hypertension.16–18

Outcome ascertainment

The primary outcomes of interest were: 30-day all-cause and CV mortality, and 30-day all-cause, CV and volume-related hospitalizations. Consistent with the USRDS definition, CV mortality was defined as a death due to: acute myocardial infarction, pericarditis including cardiac tamponade, atherosclerotic heart disease, cardiomyopathy, cardiac arrhythmia, cardiac arrest, valvular heart disease, pulmonary edema, congestive heart failure, pulmonary embolus, or stroke.14 CV hospitalizations were identified using the established USRDS claims-based definition.14 Volume-related hospitalizations were identified using a previously validated claims-based definition.19 Supplementary Table 1 displays detailed outcome definitions.

Baseline covariate determination

Demographic characteristics and comorbid conditions were identified using USRDS data (Supplementary Table 2). Laboratory and dialysis treatment covariates were identified using the dialysis organization’s clinical database. Laboratory variables and vascular access type were considered as the last baseline value. Predialysis systolic BP, interdialytic weight gain, and dialysis treatment time were considered as the mean of values in the last 30 days of the baseline period. Patients were considered to have a recent history of intradialytic hypotension if their nadir intradialytic systolic BP was <90 mm Hg in at least 30% of outpatient dialysis treatments during the last 30 days of the baseline period.3 Hospitalizations that occurred in the last 30 days of the baseline period were identified using Medicare Part A claims. Baseline utilization of antihypertensive medications was ascertained using USRDS Medicare Part D claims. Patients were considered to be taking a specific antihypertensive medication if the days supply of a prescription fill overlapped with the last day of the baseline period.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Baseline patient characteristics are described in the overall study population and across intradialytic hypertension frequency groups as count (percentage) for categorical variables and mean ± SD for continuous variables.

In primary analyses, we assessed the association between intradialytic hypertension frequency and 30-day all-cause and CV mortality, and 30-day all-cause, CV and volume-related hospitalizations (separately). Adjusted hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals were estimated with multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models. Study follow-up began immediately after the 30-day exposure assessment period. Patients surviving the exposure period were followed forward in historical time to the first occurrence of a study outcome or censoring event. Censoring events included: kidney transplantation, dialysis modality change to home hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis, loss of Medicare Part A/B coverage, no longer treated at one of the large dialysis organization’s facilities, or end of the 30-day follow-up period. In hospitalization analyses, death was treated as a censoring event. Missing covariate values were imputed using the Markov chain Monte Carlo method with 10 imputations (n = 656 for albumin, n = 374 for calcium, n = 388 for phosphorus, n = 2,243 for creatinine, n = 48 for hemoglobin, and n = 388 for equilibrated Kt/V (small solute clearance).20

In exploratory secondary analyses, we evaluated effect modification of intradialytic hypertension-outcome associations (all-cause mortality and hospitalizations) on the basis of sex (males vs. females), race (Black vs. non-Black), antihypertensive medication classification (use of ≥1 dialyzable BP medication vs. not), weekly erythropoietin simulating agent dose (≥75th vs. <75th percentile) using restriction subgroup analyses. Significance of interaction was assessed by the Wald test of nested models that did and did not include 2-way cross-product terms.

We conducted sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of our primary results. First, we expanded the study follow-up period to assess 60- and 90-day outcomes. Second, we considered alternative thresholds of predialysis to postdialysis systolic BP rise (≥5 mm Hg and ≥10 mm Hg) to identify exposure period treatments complicated by intradialytic hypertension.5,7,11 Finally, we found that 854 (2.3%) of individuals had hospitalizations that extended from the exposure period into the follow-up period. We thus repeated primary analyses excluding these individuals.

RESULTS

Study cohort characteristics

Figure 2 displays a flow diagram of study patient selection. Overall, 37,094 hemodialysis patients underwent 456,967 treatments during the exposure period (mean ± SD of 12.3 ± 1.4 treatments/patient). Patient baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. Study patients had an average age of 59.3 ± 14.9 years, 47.1% were female, 44.3% were Black and the most common cause of ESRD was diabetes (44.5%). The study cohort was comparable to the broader United States hemodialysis population in terms of age, sex and ESRD cause.1 Of the 37,094 study patients, 5,242 (14.1%) did not experience intradialytic hypertension (a predialysis to postdialysis systolic BP rise >0 mm Hg) during the exposure period. A total of 17,965 (48.4%), 10,821 (29.2%), and 3,066 (8.3%) patients exhibited intradialytic hypertension in 1–32%, 33–66%, and ≥67% of exposure period hemodialysis treatments, respectively. Individuals with more frequent intradialytic hypertension tended to be older and female, and were more likely to have diabetes, hypertension, heart failure, dialysis treatment times <240 minutes, miss more outpatient dialysis treatments, be prescribed at least 1 dialyzable antihypertensive medication, and utilize higher weekly doses of erythropoietin compared to individuals with less frequent intradialytic hypertension.

Figure 2.

Flow chart of cohort selection.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics across intradialytic hypertension frequency categories

| Characteristic | Overall, N = 37,094 | % Of exposure period treatments with intradialytic hypertensiona | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0%, n = 5,242 | 1–32%, n = 17,965 | 33–66%, n = 10,821 | ≥67%, n = 3,066 | ||

| Age (years) | 59.3 ± 14.9 | 56.5 ± 14.1 | 58.6 ± 14.9 | 60.9 ± 15.0 | 62.6 ± 14.8 |

| Female | 17,477 (47.1%) | 2,358 (45.0%) | 8,318 (46.3%) | 5,285 (48.8%) | 1,516 (49.4%) |

| Race | |||||

| White | 18,479 (49.8%) | 2,651 (50.6%) | 8,679 (48.3%) | 5,404 (49.9%) | 1,745 (56.9%) |

| Black | 16,419 (44.3%) | 2,217 (42.3%) | 8,244 (45.9%) | 4,849 (44.8%) | 1,109 (36.2%) |

| Other | 2,196 (5.9%) | 374 (7.1%) | 1,042 (5.8%) | 568 (5.2%) | 212 (6.9%) |

| Cause of ESRD | |||||

| Diabetes | 16,490 (44.5%) | 2,308 (44.0%) | 7,851 (43.7%) | 4,798 (44.3%) | 1,533 (50.0%) |

| Hypertension | 10,969 (29.6%) | 1,462 (27.9%) | 5,348 (29.8%) | 3,307 (30.6%) | 852 (27.8%) |

| Glomerular disease | 4,467 (12.0%) | 693 (13.2%) | 2,243 (12.5%) | 1,235 (11.4%) | 296 (9.7%) |

| Other | 5,168 (13.9%) | 779 (14.9%) | 2,523 (14.0%) | 1,481 (13.7%) | 385 (12.6%) |

| Diabetes | 21,778 (58.7%) | 3,033 (57.9%) | 10,374 (57.7%) | 6,428 (59.4%) | 1,943 (63.4%) |

| Hypertension | 25,812 (69.6%) | 3,415 (65.1%) | 12,192 (67.9%) | 7,871 (72.7%) | 2,334 (76.1%) |

| Heart failure | 9,806 (26.4%) | 1,089 (20.8%) | 4,353 (24.2%) | 3,304 (30.5%) | 1,060 (34.6%) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 3,293 (8.9%) | 343 (6.5%) | 1,413 (7.9%) | 1,173 (10.8%) | 364 (11.9%) |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 8,557 (23.1%) | 1,054 (20.1%) | 3,923 (21.8%) | 2,722 (25.2%) | 858 (28.0%) |

| Liver disease | 1,465 (3.9%) | 193 (3.7%) | 655 (3.6%) | 488 (4.5%) | 129 (4.2%) |

| Malignancy | 1,798 (4.8%) | 204 (3.9%) | 810 (4.5%) | 618 (5.7%) | 166 (5.4%) |

| Dialysis vintage (years) | 5.6 ± 4.7 | 6.2 ± 5.0 | 5.8 ± 4.8 | 5.4 ± 4.5 | 5.1 ± 4.2 |

| Vascular access | |||||

| Fistula | 22,226 (59.9%) | 3,327 (63.5%) | 10,806 (60.2%) | 6,276 (58.0%) | 1,817 (59.3%) |

| Graft | 9,790 (26.4%) | 1,358 (25.9%) | 4,809 (26.8%) | 2,837 (26.2%) | 786 (25.6%) |

| Catheter | 5,078 (13.7%) | 557 (10.6%) | 2,350 (13.1%) | 1,708 (15.8%) | 463 (15.1%) |

| Predialysis SBP | |||||

| ≤130 mm Hg | 5,283 (14.2%) | 303 (5.8%) | 2,091 (11.6%) | 2,122 (19.6%) | 767 (25.0%) |

| 131–150 mm Hg | 11,650 (31.4%) | 1,291 (24.6%) | 5,553 (30.9%) | 3,686 (34.1%) | 1,120 (36.5%) |

| 151–170 mm Hg | 12,815 (34.5%) | 2,046 (39.0%) | 6,453 (35.9%) | 3,432 (31.7%) | 884 (28.8%) |

| ≥171 mm Hg | 7,346 (19.8%) | 1,602 (30.6%) | 3,868 (21.5%) | 1,581 (14.6%) | 295 (9.6%) |

| Interdialytic weight gain (kg) | 2.7 ± 1.2 | 3.0 ± 1.2 | 2.8 ± 1.2 | 2.6 ± 1.2 | 2.4 ± 1.2 |

| Delivered treatment time <240 minutes | 29,837 (80.4%) | 4,143 (79.0%) | 14,356 (79.9%) | 8,772 (81.1%) | 2,566 (83.7%) |

| ≥3 Missed dialysis treatments | 13,648 (36.8%) | 1,814 (34.6%) | 6,304 (35.1%) | 4,344 (40.1%) | 1,186 (38.7%) |

| Intradialytic hypotensionb | 5,937 (16.0%) | 1,126 (21.5%) | 3,027 (16.8%) | 1,459 (13.5%) | 325 (10.6%) |

| Weekly ESA dose | |||||

| ≤5,390 units | 9,462 (25.5%) | 1,554 (29.6%) | 4,809 (26.8%) | 2,481 (22.9%) | 618 (20.2%) |

| 5,391–12,577 units | 9,096 (24.5%) | 1,336 (25.5%) | 4,545 (25.3%) | 2,552 (23.6%) | 663 (21.6%) |

| 12,578–24,640 units | 9,411 (25.4%) | 1,268 (24.2%) | 4,470 (24.9%) | 2,848 (26.3%) | 825 (26.9%) |

| ≥24,641 units | 9,125 (24.6%) | 1,084 (20.7%) | 4,141 (23.1%) | 2,940 (27.2%) | 960 (31.3%) |

| Albuminc | |||||

| ≤3.0 g/dl | 1,050 (2.8%) | 71 (1.4%) | 410 (2.3%) | 423 (3.9%) | 146 (4.8%) |

| 3.1–3.5 g/dl | 4,648 (12.5%) | 487 (9.3%) | 2,014 (11.2%) | 1,633 (15.1%) | 514 (16.8%) |

| 3.6–4.0 g/dl | 17,705 (47.7%) | 2,468 (47.1%) | 8,635 (48.1%) | 5,121 (47.3%) | 1,481 (48.3%) |

| >4.0 g/dl | 13,691 (36.9%) | 2,216 (42.3%) | 6,906 (38.4%) | 3,644 (33.7%) | 925 (30.2%) |

| Calciumc | |||||

| ≤8.6 mg/dl | 9,397 (25.3%) | 1,119 (21.3%) | 4,333 (24.1%) | 2,952 (27.3%) | 993 (32.4%) |

| 8.7–9.0 mg/dl | 9,292 (25.0%) | 1,249 (23.8%) | 4,496 (25.0%) | 2,760 (25.5%) | 787 (25.7%) |

| 9.1–9.4 mg/dl | 10,276 (27.7%) | 1,526 (29.1%) | 5,038 (28.0%) | 2,910 (26.9%) | 802 (26.2%) |

| ≥9.5 mg/dl | 8,129 (21.9%) | 1,348 (25.7%) | 4,098 (22.8%) | 2,199 (20.3%) | 484 (15.8%) |

| Phosphorusc | |||||

| ≤4.0 mg/dl | 7,881 (21.2%) | 831 (15.9%) | 3,555 (19.8%) | 2,620 (24.2%) | 875 (28.5%) |

| 4.1–5.0 mg/dl | 10,920 (29.4%) | 1,484 (28.3%) | 5,261 (29.3%) | 3,191 (29.5%) | 984 (32.1%) |

| 5.1–6.0 mg/dl | 8,716 (23.5%) | 1,297 (24.7%) | 4,316 (24.0%) | 2,453 (22.7%) | 650 (21.2%) |

| >6.0 mg/dl | 9,577 (25.8%) | 1,630 (31.1%) | 4,833 (26.9%) | 2,557 (23.6%) | 557 (18.2%) |

| Creatinine (mg/dl)c | 9.0 ± 3.0 | 9.6 ± 2.9 | 9.2 ± 3.0 | 8.6 ± 3.0 | 8.0 ± 2.8 |

| Hemoglobinc | |||||

| <9.5 g/dl | 1,403 (3.8%) | 138 (2.6%) | 589 (3.3%) | 496 (4.6%) | 180 (5.9%) |

| 9.6–11.9 g/dl | 20,793 (56.1%) | 2,851 (54.4%) | 10,019 (55.8%) | 6,134 (56.7%) | 1,789 (58.3%) |

| ≥12.0 g/dl | 14,898 (40.2%) | 2,253 (43.0%) | 7,357 (41.0%) | 4,191 (38.7%) | 1,097 (35.8%) |

| Equilibrated Kt/Vc | 2.07 ± 0.39 | 2.05 ± 0.38 | 2.06 ± 0.39 | 2.08 ± 0.40 | 2.13 ± 0.41 |

| Recent hospitalizationd | 3,981 (10.7%) | 383 (7.3%) | 1,699 (9.5%) | 1,453 (13.4%) | 446 (14.5%) |

| ≥1 Dialyzable antihypertensive medicatione | 16,208 (43.7%) | 2,155 (41.1%) | 7,706 (42.9%) | 4,885 (45.1%) | 1,462 (47.7%) |

| ACE inhibitor/ARB | 13,650 (36.8%) | 1,767 (33.7%) | 6,338 (35.3%) | 4,160 (38.4%) | 1,385 (45.2%) |

| Beta blocker | 17,015 (45.9%) | 2,104 (40.1%) | 7,838 (43.6%) | 5,320 (49.2%) | 1,753 (57.2%) |

| Calcium channel blocker | 14,165 (38.2%) | 1,586 (30.3%) | 6,482 (36.1%) | 4,558 (42.1%) | 1,539 (50.2%) |

| Central alpha agonist | 5,915 (15.9%) | 568 (10.8%) | 2,573 (14.3%) | 2,007 (18.5%) | 767 (25.0%) |

| Diuretic | 3,960 (10.7%) | 493 (9.4%) | 1,832 (10.2%) | 1,248 (11.5%) | 387 (12.6%) |

| Vasodilator | 5,295 (14.3%) | 705 (13.4%) | 2,494 (13.9%) | 1,560 (14.4%) | 536 (17.5%) |

| Long-acting nitrate | 2,974 (8.0%) | 278 (5.3%) | 1,233 (6.9%) | 1,060 (9.8%) | 403 (13.1%) |

Values are given as number (percentage) for categorical variables and as mean ± SD for continuous variables. Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

aIn primary analyses, a single episode of intradialytic hypertension was defined as a predialysis to postdialysis systolic BP rise >0 mm Hg.

bIntradialytic hypotension, low blood pressure during dialysis, was defined using the Flythe et al. definition.3 Patients were considered as having baseline intradialytic hypotension if they had an intradialytic nadir systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg in at least 30% of outpatient dialysis treatments in the last 30 days of the baseline period.

cValues were imputed using Markov chain Monte Carlo method using 10 imputations when missing (n = 656 for albumin, n = 374 for calcium, n = 388 for phosphorus, n = 2,243 for creatinine, n = 48 for hemoglobin, and n = 388 for equilibrated Kt/V).

dHospitalized in the last 30 days of the baseline period.

eDialyzable antihypertensive medications include: acebutolol, atenolol, captopril, enalapril, lisinopril, methyldopa, metoprolol, minoxidil, nadolol, perindopril, sotalol, trandolapril.23–25

Primary analyses

During the 30-day follow-up period, there were 476 all-cause (15.7/100 person-years) and 215 CV (7.1/100 person-years) deaths. Figure 3 depicts the association between intradialytic hypertension frequency and 30-day all-cause and CV mortality. More frequent intradialytic hypertension was associated with incremental increases in 30-day all-cause and CV mortality. Patients who experienced intradialytic hypertension in ≥67% (vs. 0%) of exposure period treatments had the highest hazard for death (adjusted hazard ratio [95% confidence interval]: 2.57 [1.68, 3.94] for all-cause mortality and 3.68 [1.89, 7.15] for CV mortality). Subgroup analyses evaluating the association between intradialytic hypertension frequency and all-cause mortality across strata of sex, race, dialyzable antihypertensive medication use, and erythropoiesis stimulating agent (ESA) dose produced consistent results (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Association between intradialytic hypertension frequency and 30-day mortality. A single episode of intradialytic hypertension was defined as a predialysis to postdialysis systolic BP rise >0 mm Hg. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate the associations between intradialytic hypertension frequency and all-cause mortality (a) and cardiovascular mortality (b). Models were adjusted for the baseline covariates listed in Table 1. All y-axes scales are natural log transformed. Abbreviations: BP, blood pressure; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; ref, referent.

Table 2.

Association between intradialytic hypertension frequency and 30-day all-cause mortality and hospitalizations within subgroupsa,b

| Subgroup | n | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | P c | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Of exposure period treatments with intradialytic hypertension | ||||||

| 0% | 1–32% | 33–66% | ≥67% | |||

| All-cause mortality | ||||||

| Sex | 0.25 | |||||

| Males | 19,617 | 1.00 (ref.) | 1.48 (0.85, 2.58) | 2.79 (1.59, 4.89) | 3.75 (2.02, 6.97) | |

| Females | 17,477 | 1.00 (ref.) | 1.00 (0.60, 1.65) | 1.23 (0.73, 2.07) | 1.79 (0.99, 3.23) | |

| Race | 0.31 | |||||

| Black | 16,419 | 1.00 (ref.) | 0.83 (0.47, 1.45) | 1.23 (0.69, 2.19) | 1.81 (0.92, 3.55) | |

| Non-Black | 20,675 | 1.00 (ref.) | 1.56 (0.94, 2.59) | 2.48 (1.48, 4.14) | 3.19 (1.82, 5.59) | |

| BP medication used | 0.74 | |||||

| <1 Dialyzable drug | 10,454 | 1.00 (ref.) | 0.83 (0.47, 1.45) | 1.21 (0.68, 2.15) | 1.82 (0.93, 3.56) | |

| ≥1 Dialyzable drug | 16,208 | 1.00 (ref.) | 1.54 (0.93, 2.56) | 2.43 (1.45, 4.05) | 3.16 (1.80, 5.54) | |

| Weekly ESA dosee | 0.97 | |||||

| <24,641 units | 27,969 | 1.00 (ref.) | 1.07 (0.51, 2.23) | 1.62 (0.77, 3.39) | 1.94 (0.84, 4.51) | |

| ≥24,641 units | 9,125 | 1.00 (ref.) | 1.98 (0.98, 3.99) | 2.86 (1.40, 5.84) | 3.49 (1.60, 7.62) | |

| All-cause hospitalizations | ||||||

| Sex | 0.02 | |||||

| Males | 19,617 | 1.00 (ref.) | 1.24 (1.08, 1.42) | 1.56 (1.35, 1.80) | 1.68 (1.41, 2.01) | |

| Females | 17,477 | 1.00 (ref.) | 1.07 (0.94, 1.22) | 1.22 (1.06, 1.40) | 1.20 (1.01, 1.44) | |

| Race | 0.64 | |||||

| Black | 16,419 | 1.00 (ref.) | 1.19 (1.03, 1.38) | 1.46 (1.25, 1.71) | 1.50 (1.23, 1.84) | |

| Non-Black | 20,675 | 1.00 (ref.) | 1.13 (1.00, 1.28) | 1.32 (1.16, 1.51) | 1.36 (1.16, 1.60) | |

| BP medication used | 0.51 | |||||

| <1 dialyzable drug | 10,454 | 1.00 (ref.) | 1.20 (1.00, 1.45) | 1.36 (1.12, 1.65) | 1.29 (1.01, 1.65) | |

| ≥1 dialyzable drug | 16,208 | 1.00 (ref.) | 1.20 (1.03, 1.39) | 1.46 (1.25, 1.71) | 1.47 (1.21, 1.78) | |

| Weekly ESA dosee | 0.97 | |||||

| <24,641 units | 27,969 | 1.00 (ref.) | 1.16 (1.03, 1.30) | 1.38 (1.22, 1.56) | 1.43 (1.22, 1.67) | |

| ≥24,641 units | 9,125 | 1.00 (ref.) | 1.17 (0.98, 1.38) | 1.41 (1.18, 1.68) | 1.42 (1.14, 1.75) | |

Abbreviations: BP, blood pressure; CI, confidence interval; ESA, erythropoiesis stimulating agent; HR, hazard ratio.

aA single episode of intradialytic hypertension was defined as a predialysis to postdialysis systolic BP rise >0 mm Hg.

bMultivariable Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate the associations between intradialytic hypertension frequency and all-cause mortality and hospitalizations within each subgroup. Models were adjusted for the baseline covariates listed in Table 1. Effect modifiers of interest were excluded from the applicable adjustments.

cValues represent P for interaction. The significance of interaction terms was determined using the Wald test.

dSubgroup analysis restricted to a total 26,662 patients taking a at least 1 antihypertensive medication. Dialyzable antihypertensive medications include: acebutolol, atenolol, captopril, enalapril, lisinopril, methyldopa, metoprolol, minoxidil, nadolol, perindopril, sotalol, trandolapril.23–25

eThe ESA dose categories were dichotomized at 75th percentile, 24,641 units/week.

During the 30-day follow-up period, there were 5,091 all-cause (181.0/100 person-years), 1,639 CV (55.5/100 person-years), and 232 volume-related (7.7/100 person-years) hospitalizations. Figure 4 illustrates the association between intradialytic hypertension frequency and 30-day all-cause, CV, and volume-related hospitalizations. Similar to mortality, patients with more frequent (vs. less frequent) intradialytic hypertension had a higher hazard of initial all-cause, CV, and volume-related hospitalizations. Subgroup analyses evaluating the association between intradialytic hypertension frequency and all-cause hospitalizations across strata of sex, race, dialyzable antihypertensive medication use, and ESA dose produced consistent results (Table 2).

Figure 4.

Association between intradialytic hypertension frequency and 30-day hospitalizations. A single episode of intradialytic hypertension was defined as a predialysis to postdialysis systolic BP rise >0 mm Hg. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate the associations between intradialytic hypertension frequency and all-cause hospitalizations (a), cardiovascular hospitalizations (b) and volume-related hospitalizations (c). Models were adjusted for the baseline covariates listed in Table 1. All y-axes scales are natural log transformed. Abbreviations: BP, blood pressure; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; ref, referent.

Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analyses considering 60- and 90-day outcomes yielded results analogous to primary analyses (Table 3). Experiencing a predialysis to postdialysis systolic BP rise >0 mm Hg more (vs. less) frequently was associated with greater 60- and 90-day mortality and hospitalizations. Employing alternative systolic BP thresholds (predialysis to postdialysis systolic BP rise ≥5 mm Hg and ≥10 mm Hg) to define episodes of intradialytic hypertension resulted in findings similar to primary analyses (Table 4). More frequent intradialytic hypertension, regardless of systolic BP threshold used, was associated with increased 30-day all-cause and CV mortality and 30-day all-cause, CV, and volume-related hospitalizations. Sensitivity analyses excluding individuals who had a hospitalization that extended from the exposure period into the follow-up period also yielded results similar to primary analyses (Supplementary Table 3).

Table 3.

Association between intradialytic hypertension frequency and 60- and 90-day mortality and hospitalizationsa,b

| Adjusted HR (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Of exposure period treatments with intradialytic hypertension | ||||

| Outcome | 0%, n = 5,242 | 1–32%, n = 17,965 | 33–66%, n = 10,821 | ≥67%, n = 3,066 |

| All-cause mortality | ||||

| 60-Day follow-up | 1.00 (ref.) | 1.23 (0.96, 1.57) | 1.55 (1.20, 2.01) | 1.93 (1.45, 2.59) |

| 90-Day follow-up | 1.00 (ref.) | 1.20 (0.98, 1.46) | 1.50 (1.22, 1.84) | 1.73 (1.36, 2.20) |

| Cardiovascular mortality | ||||

| 60-Day follow-up | 1.00 (ref.) | 1.48 (0.99, 2.21) | 1.89 (1.25, 2.85) | 2.78 (1.76, 4.40) |

| 90-Day follow-up | 1.00 (ref.) | 1.58 (1.13, 2.19) | 1.95 (1.39, 2.74) | 2.65 (1.81, 3.88) |

| All-cause hospitalizations | ||||

| 60-Day follow-up | 1.00 (ref.) | 1.15 (1.07, 1.24) | 1.36 (1.26, 1.47) | 1.38 (1.25, 1.52) |

| 90-Day follow-up | 1.00 (ref.) | 1.15 (1.08, 1.22) | 1.33 (1.25, 1.43) | 1.38 (1.27, 1.51) |

| Cardiovascular hospitalizations | ||||

| 60-Day follow-up | 1.00 (ref.) | 1.20 (1.06, 1.36) | 1.55 (1.36, 1.77) | 1.53 (1.29, 1.80) |

| 90-Day follow-up | 1.00 (ref.) | 1.17 (1.05, 1.30) | 1.49 (1.33, 1.67) | 1.59 (1.38, 1.83 |

| Volume-related hospitalizations | ||||

| 60-Day follow-up | 1.00 (ref.) | 1.16 (0.83, 1.61) | 1.40 (0.99, 1.98) | 1.43 (0.92, 2.21) |

| 90-Day follow-up | 1.00 (ref.) | 0.97 (0.75, 1.25) | 1.20 (0.91, 1.57) | 1.30 (0.92, 1.85) |

Abbreviations: BP, blood pressure; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

aA single episode of intradialytic hypertension was defined as a predialysis to postdialysis systolic BP rise >0 mm Hg.

bMultivariable Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate the associations between intradialytic hypertension frequency and each clinical outcome. Models were adjusted for the baseline covariates listed in Table 1.

Table 4.

Association between intradialytic hypertension frequency defined using alternative blood pressure thresholds and 30-day outcomesa

| Adjusted HR (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Predialysis to postdialysis systolic BP rise | |||

| Outcome | % Of exposure period treatments affected | ≥5 mm Hgb | ≥10 mm Hgc |

| All-cause mortality | 0% | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref.) |

| 1–32% | 1.05 (0.77, 1.42) | 1.07 (0.83, 1.38) | |

| 33–66% | 1.76 (1.28, 2.41) | 1.78 (1.34, 2.37) | |

| ≥67% | 2.02 (1.35, 3.03) | 2.14 (1.36, 3.36) | |

| Cardiovascular mortality | 0% | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| 1–32% | 1.21 (0.77, 1.90) | 1.10 (0.76, 1.60) | |

| 33–66% | 1.83 (1.13, 2.95) | 2.15 (1.42, 3.27) | |

| ≥67% | 2.40 (1.31, 4.39) | 1.91 (0.93, 3.93) | |

| All-cause hospitalizations | 0% | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| 1–32% | 1.15 (1.06, 1.24) | 1.15 (1.07, 1.23) | |

| 33–66% | 1.34 (1.22, 1.47) | 1.33 (1.22, 1.45) | |

| ≥67% | 1.38 (1.21, 1.58) | 1.41 (1.20, 1.66) | |

| Cardiovascular hospitalizations | 0% | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| 1–32% | 1.18 (1.01, 1.36) | 1.12 (0.99, 1.27) | |

| 33–66% | 1.56 (1.32, 1.83) | 1.44 (1.24, 1.68) | |

| ≥67% | 1.59 (1.26, 2.00) | 1.59 (1.21, 2.09) | |

| Volume-related hospitalizations | 0% | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| 1–32% | 1.00 (0.68, 1.46) | 1.26 (0.90, 1.77) | |

| 33–66% | 1.33 (0.87, 2.03) | 1.45 (0.95, 2.21) | |

| ≥67% | 2.20 (1.28, 3.79) | 2.74 (1.47, 5.10) | |

Abbreviations: BP, blood pressure; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

aMultivariable Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate the associations between intradialytic hypertension frequency and each clinical outcome. Models were adjusted for the baseline covariates listed in Table 1.

bOf the 37,094 study patients, 7,292 (19.7%), 19,319 (52.1%), 8,614 (23.2%), and 1,869 (5.0%) exhibited a predialysis to postdialysis systolic BP rise ≥5 mm Hg in 0%, 1–32%, 33–66%, and ≥67% of exposure period treatments, respectively.

cOf the 37,094 study patients, 10,477 (28.2%), 19,743 (53.2%), 5,929 (16.0%), and 945 (2.5%) exhibited a predialysis to postdialysis systolic BP rise ≥10 mm Hg in 0%, 1–32%, 33–66%, and ≥67% of exposure period treatments, respectively.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study demonstrating an association between intradialytic hypertension and an increased risk of 30-day mortality and hospitalizations. We demonstrated that more frequent intradialytic hypertension was associated with incremental increases in 30-day mortality (all-cause and CV) and hospitalizations (all-cause, CV, and volume-related). Our findings were robust across different: lengths of study follow-up, definitions of intradialytic hypertension, and clinically relevant subgroups.

Prior observational studies have shown an association between intradialytic hypertension and long-term mortality. In a cohort of incident United States hemodialysis patients, Inrig et al. found that every 10 mm Hg increase in predialysis to postdialysis systolic BP was associated with a 6% increase in the 2-year all-cause mortality rate.6 In a prospective study of 115 Taiwanese hemodialysis patients, Yang et al. reported that an average change in systolic BP from predialysis to postdialysis >5 mm Hg (vs. ≤5 mm Hg) was associated with higher 4-year all-cause mortality.7 In a retrospective analysis of 3,196 Italian hemodialysis patients without heart failure, Losito et al. noted that an average predialysis to postdialysis systolic BP change >10 mm Hg (vs. a BP change between −20 mm Hg and 10 mm Hg) was associated increased CV mortality over a mean follow-up time of 26.8 months.11 In the largest observational study to date (N = 113,255), Park et al. demonstrated that a predialysis to postdialysis systolic BP rise was incrementally associated with greater all-cause and CV mortality over a median follow-up time of 2.2 years.10 Less data exist regarding intradialytic hypertension and short-term outcomes. In a post-hoc analysis of the Crit-Line Intradialytic Monitoring Benefit Study, Inrig et al. found that patients with an average increase in predialysis to postdialysis systolic BP ≥10 mm Hg (vs. <10 mm Hg) had roughly 2 times the odds of a composite outcome of nonvascular access-related hospitalization or death at 6 months.5 Our findings of an incremental association between intradialytic hypertension frequency and the occurrence of 30-day hospitalizations and mortality support and expand the evidence-base.

In the studies highlighted above, intradialytic hypertension was specified as a mean-based exposure, whereby the predialysis to postdialysis systolic BP changes from individual hemodialysis treatments were averaged at the patient-level over varying exposure assessment period lengths (ranging from 1 week to 3 months).5–7,10 However, arithmetic means are sensitive to extreme values, and outliers may overinfluence results. Such an effect is more likely when fewer BP measurements (i.e., shorter exposure assessment periods) are used to characterize mean-based intradialytic hypertension. In addition, mean-based exposure definitions may obscure outcome associations in settings where both positive (BP rise) and negative (BP fall) values may occur. Alternatively, we defined intradialytic hypertension using a frequency-based approach. This strategy may better capture the physiologic burden of repeated intradialytic hypertension episodes. Unlike mean-based intradialytic hypertension definitions, utilization of a frequency-based definition also facilitates study of an abnormal intradialytic BP phenotype that can be easily identified in routine clinical practice.

Numerous pathophysiologic mechanisms including volume overload, endothelial dysfunction, sympathetic nervous system overactivity, and renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system activation may play roles in the pathogenesis of intradialytic hypertension. Intradialytic hypertension is often attributed to volume overload. In a cross-sectional study, Nongnuch et al. reported that patients who experienced a predialysis to postdialysis systolic BP rise (vs. not) had higher predialysis and postdialysis extracellular water to total body water ratios and lower ultrafiltration volumes.12 Additionally, intensification of ultrafiltration has been shown to improve BP, ejection fraction, and cardiac output among individuals with intradialytic hypertension.15 Our data provide further support for a link between volume status and intradialytic hypertension. We found that patients who experienced more frequent intradialytic hypertension had an incrementally higher hazard of 30-day volume-related hospitalizations.

Beyond volume overload, endothelial dysfunction may also contribute to the development of intradialytic hypertension. Among hemodialysis patients prone to intradialytic hypertension, serum endothelin-1 (a vasoconstrictor) concentrations tend to rise during dialysis, and compensatory serum nitric oxide (a vasodilator) levels remain low, resulting in increased peripheral vascular resistance.17 Historically, ESA use was a notable contributor to intradialytic hypertension via its dose-dependent influence on endothelin-1 production.21 In the modern era of restricted ESA dosing, the role of ESAs in the development of intradialytic hypertension is likely diminished. Additionally, another modifiable factor that may be involved in the development of intradialytic hypertension is the utilization of antihypertensive medications that are extensively cleared by hemodialysis. Our findings potentially support this idea. We observed that dialyzable BP medication use was more common among patients experiencing more frequent intradialytic hypertension. However, dialyzable antihypertensive medication use (vs. non-dialyzable antihypertensive medication use) did not significantly modify the association between intradialytic hypertension frequency and 30-day all-cause mortality and hospitalizations.

Our results indicate that intradialytic hypertension may be a risk marker for impending adverse events secondary to volume overload and suggest that prompt volume assessment among hemodialysis patients who experience frequent episodes of intradialytic hypertension is warranted. In fact, challenging prescribed target (estimated “dry”) weight via increased ultrafiltration has been shown to improve intradialytic hypertension.22 Other interventions that promote postdialysis euvolemia, such as extending dialysis treatment times and the provision of extra dialysis treatments, may also be helpful. For patients who remain prone to recurrent intradialytic hypertension despite volume challenge, antihypertensive medication regimens should be re-evaluated. The practice of withholding antihypertensive medications prior to dialysis treatments may promote a predialysis to postdialysis BP rise. Additionally, it may be prudent to avoid dialyzable antihypertensive medications. For example, carvedilol is not extensively removed by dialysis23–25 and has been shown to modestly improve vascular endothelial function and reduce the occurrence of intradialytic hypertension.26

Our study has many strengths. We utilized data from a large, contemporary cohort with detailed clinical and administrative claims data and, we chose a study design with discrete baseline, exposure and follow-up periods to minimize immortal person time and selection biases. Additionally, we identified intradialytic hypertension using a clinically applicable, frequency-based definition. However, our results should be considered in the context of study limitations. First, our study was observational, and it is possible that residual confounding may exist. To minimize the influence of confounding from difficult-to-measure factors such as ambient health status, we controlled for variables including albumin, phosphorus, and creatinine. Nonetheless, it is possible that our results could have been confounded by unmeasured differences across intradialytic hypertension frequency groups. Second, predialysis and postdialysis BP measurements were taken during routine clinical care and were not standardized. Finally, our study included adult, center-based hemodialysis patients with dialytic vintage of 1 year or longer. Results should not be extrapolated to excluded populations such as incident dialysis patients.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that the occurrence of more frequent intradialytic hypertension was associated with incremental increases in 30-day mortality and hospitalizations among prevalent hemodialysis patients. Our data indicate that intradialytic hypertension may be an important short-term risk marker in the hemodialysis population.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary data are available at American Journal of Hypertension online.

DISCLOSURE

M.M.A. and J.E.F. have received have received investigator initiated research funding from the Renal Research Institute, a subsidiary of Fresenius Medical Care, North America. J.E.F. has received speaking honoraria from Dialysis Clinic Incorporated, Renal Ventures, American Renal Associates, American Society of Nephrology, Baxter, National Kidney Foundation, and multiple universities. L.W. has no relevant conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

M.M.A. is supported by grant F32 DK109561 and J.E.F. by grant K23 DK109401, both awarded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health. Some of the data reported here have been supplied by DaVita Clinical Research. DaVita Clinical Research had no role in the design or implementation of this study or the in the decision to publish. Additionally, some of the data reported here have been provided by the United States Renal Data System. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as official policy or interpretation of the United States government.

REFERENCES

- 1. Saran R, Robinson B, Abbott KC, Agodoa LY, Albertus P, Ayanian J, Balkrishnan R, Bragg-Gresham J, Cao J, Chen JL, Cope E, Dharmarajan S, Dietrich X, Eckard A, Eggers PW, Gaber C, Gillen D, Gipson D, Gu H, Hailpern SM, Hall YN, Han Y, He K, Hebert H, Helmuth M, Herman W, Heung M, Hutton D, Jacobsen SJ, Ji N, Jin Y, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kapke A, Katz R, Kovesdy CP, Kurtz V, Lavalee D, Li Y, Lu Y, McCullough K, Molnar MZ, Montez-Rath M, Morgenstern H, Mu Q, Mukhopadhyay P, Nallamothu B, Nguyen DV, Norris KC, O’Hare AM, Obi Y, Pearson J, Pisoni R, Plattner B, Port FK, Potukuchi P, Rao P, Ratkowiak K, Ravel V, Ray D, Rhee CM, Schaubel DE, Selewski DT, Shaw S, Shi J, Shieu M, Sim JJ, Song P, Soohoo M, Steffick D, Streja E, Tamura MK, Tentori F, Tilea A, Tong L, Turf M, Wang D, Wang M, Woodside K, Wyncott A, Xin X, Zang W, Zepel L, Zhang S, Zho H, Hirth RA, Shahinian V. US Renal Data System 2016 Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis 2017; 69:A7–A8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dinesh K, Kunaparaju S, Cape K, Flythe JE, Feldman HI, Brunelli SM. A model of systolic blood pressure during the course of dialysis and clinical factors associated with various blood pressure behaviors. Am J Kidney Dis 2011; 58:794–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Flythe JE, Xue H, Lynch KE, Curhan GC, Brunelli SM. Association of mortality risk with various definitions of intradialytic hypotension. J Am Soc Nephrol 2015; 26:724–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chou JA, Streja E, Nguyen DV, Rhee CM, Obi Y, Inrig JK, Amin A, Kovesdy CP, Sim JJ, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Intradialytic hypotension, blood pressure changes and mortality risk in incident hemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2017; e-pub ahead of print. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=28444336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Inrig JK, Oddone EZ, Hasselblad V, Gillespie B, Patel UD, Reddan D, Toto R, Himmelfarb J, Winchester JF, Stivelman J, Lindsay RM, Szczech LA. Association of intradialytic blood pressure changes with hospitalization and mortality rates in prevalent ESRD patients. Kidney Int 2007; 71:454–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Inrig JK, Patel UD, Toto RD, Szczech LA. Association of blood pressure increases during hemodialysis with 2-year mortality in incident hemodialysis patients: a secondary analysis of the Dialysis Morbidity and Mortality Wave 2 Study. Am J Kidney Dis 2009; 54:881–890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yang CY, Yang WC, Lin YP. Postdialysis blood pressure rise predicts long-term outcomes in chronic hemodialysis patients: a four-year prospective observational cohort study. BMC Nephrol 2012; 13:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Van Buren PN, Kim C, Toto RD, Inrig JK. The prevalence of persistent intradialytic hypertension in a hemodialysis population with extended follow-up. Int J Artif Organs 2012; 35:1031–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Assimon MM, Flythe JE. Intradialytic blood pressure abnormalities: the highs, the lows and all that lies between. Am J Nephrol 2015; 42:337–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Park J, Rhee CM, Sim JJ, Kim YL, Ricks J, Streja E, Vashistha T, Tolouian R, Kovesdy CP, Kalantar-Zadeh K. A comparative effectiveness research study of the change in blood pressure during hemodialysis treatment and survival. Kidney Int 2013; 84:795–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Losito A, Del Vecchio L, Del Rosso G, Locatelli F. Postdialysis hypertension: associated factors, patient profiles, and cardiovascular mortality. Am J Hypertens 2016; 29:684–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nongnuch A, Campbell N, Stern E, El-Kateb S, Fuentes L, Davenport A. Increased postdialysis systolic blood pressure is associated with extracellular overhydration in hemodialysis outpatients. Kidney Int 2015; 87:452–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Van Buren PN, Zhou Y, Neyra JA, Xiao G, Vongpatanasin W, Inrig J, Toto R. Extracellular volume overload and increased vasoconstriction in patients with recurrent intradialytic hypertension. Kidney Blood Press Res 2016; 41:802–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. United States Renal Data System. ESRD Analytic Methods, 2016. <https://www.usrds.org/2016/view/v2_00_appx.aspx>. Accessed 07 July 2017.

- 15. Cirit M, Akçiçek F, Terzioğlu E, Soydaş C, Ok E, Ozbaşli CF, Başçi A, Mees EJ. ‘Paradoxical’ rise in blood pressure during ultrafiltration in dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1995; 10:1417–1420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Raj DS, Vincent B, Simpson K, Sato E, Jones KL, Welbourne TC, Levi M, Shah V, Blandon P, Zager P, Robbins RA. Hemodynamic changes during hemodialysis: role of nitric oxide and endothelin. Kidney Int 2002; 61:697–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chou KJ, Lee PT, Chen CL, Chiou CW, Hsu CY, Chung HM, Liu CP, Fang HC. Physiological changes during hemodialysis in patients with intradialysis hypertension. Kidney Int 2006; 69:1833–1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Inrig JK, Van Buren P, Kim C, Vongpatanasin W, Povsic TJ, Toto RD. Intradialytic hypertension and its association with endothelial cell dysfunction. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2011; 6:2016–2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Assimon MM, Nguyen T, Katsanos SL, Brunelli SM, Flythe JE. Identification of volume overload hospitalizations among hemodialysis patients using administrative claims: a validation study. BMC Nephrol 2016; 17:173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schafer JL. Multiple imputation: a primer. Stat Methods Med Res 1999; 8:3–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kang DH, Yoon KI, Han DS. Acute effects of recombinant human erythropoietin on plasma levels of proendothelin-1 and endothelin-1 in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1998; 13:2877–2883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Agarwal R, Light RP. Intradialytic hypertension is a marker of volume excess. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2010; 25:3355–3361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Aronoff GR, Aronoff GR; American College of Physicians . Drug Prescribing in Renal Failure: Dosing Guidelines for Adults and Children, 5th edn. American College of Physicians; Royal Society of Medicine: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bailie GR, Mason NA.. Bailie and Mason’s 2016 Dialysis of Drugs. Renal Pharmacy Consultants, LLC: Saline, Michigan; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tieu A, Leither M, Urquhart BL, Weir MA. Clearance of cardiovascular medications during hemodialysis. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2016; 25:257–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Inrig JK, Van Buren P, Kim C, Vongpatanasin W, Povsic TJ, Toto R. Probing the mechanisms of intradialytic hypertension: a pilot study targeting endothelial cell dysfunction. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2012; 7:1300–1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.