Abstract

BACKGROUND

Health care access is an important determinant of health. We assessed the effect of health insurance status and type on blood pressure control among US women living with (WLWH) and without HIV.

METHODS

We used longitudinal cohort data from the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS). WIHS participants were included at their first study visit since 2001 with incident uncontrolled blood pressure (BP) (i.e., BP ≥140/90 and at which BP at the prior visit was controlled (i.e., <135/85). We assessed time to regained BP control using inverse Kaplan–Meier curves and Cox proportional hazard models. Confounding and selection bias were accounted for using inverse probability-of-exposure-and-censoring weights.

RESULTS

Most of the 1,130 WLWH and 422 HIV-uninfected WIHS participants who had an elevated systolic or diastolic measurement were insured via Medicaid, were African-American, and had a yearly income ≤$12,000. Among participants living with HIV, comparing the uninsured to those with Medicaid yielded an 18-month BP control risk difference of 0.16 (95% CI: 0.10, 0.23). This translates into a number-needed-to-treat (or insure) of 6; to reduce the caseload of WLWH with uncontrolled BP by one case, five individuals without insurance would need to be insured via Medicaid. Blood pressure control was similar among WLWH with private insurance and Medicaid. There were no differences observed by health insurance status on 18-month risk of BP control among the HIV-uninfected participants.

CONCLUSIONS

These results underscore the importance of health insurance for hypertension control—especially for people living with HIV.

Keywords: blood pressure, health insurance, HIV, hypertension, women.

Health care availability and quality are important determinants of health.1 About 15% of the United States (US) population lacked health insurance prior to the Affordable Care Act; Blacks and Hispanics, racial/ethnic groups that are disproportionately both poor and affected by HIV and hypertension, were more likely to be uninsured.2 The positive effect of health insurance on blood pressure control has been documented in the general population. For example, an analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey from 1999 to 2002 showed that among participants with hypertension, the uninsured were less likely than the insured to have had recent blood pressure monitoring, to be taking antihypertensive medications, and to have adequately controlled blood pressure.3 In the Women’s Health Initiative, women on Medicaid were given medication to treat hypertension at a rate of 81%—higher than treatment rates among women with private insurance (63–65%) or Medicare only (64%).4 In this same study, participants seeing a health care provider in the past year were four times as likely to be on medication to control hypertension as those who had not seen a provider. These positive effects of health insurance on blood pressure control are likely due to a combination of reduction in cost barriers to seeking healthcare, increased screening for hypertension, appropriate lifestyle counseling, and prescription coverage of antihypertensive drugs.

Some individuals living with HIV may also have coverage of antihypertensive medications through the AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP), a federal program that provides HIV-related prescription drugs to low-income individuals with limited or no prescription drug coverage. Individual states set the requirements for ADAP eligibility and drug formularies, and non-HIV medication coverage. For example, in 2015, New York and Illinois covered antihypertensive medications, but California did not.5 There has been limited research about the effects of ADAP on hypertension control. In one study among WIHS WLWH diagnosed with hypertension, women enrolled in ADAP showed a nonsignificant trend toward increased use of antihypertensive medications.6

While there have been studies on predictors of incident or prevalent hypertension among WLWH, to our knowledge there have been no prospective studies of health insurance type on blood pressure control among individuals living with HIV.

METHODS

Women’s Interagency HIV Study.

Recruitment, retention, and study characteristics of WIHS participants have been previously reported.7,8 In brief, WLWH and HIV-uninfected women were recruited to participate in WIHS during four waves, during calendar years 1994–1995, 2001–2002, 2011–2012, and 2013–2015. This report includes women recruited during the first three waves. This included participants from Brooklyn, Bronx, Chicago, Washington DC, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. Study visits are conducted approximately every six months and consist of a structured interview, clinical examination, and specimen collection. To assess time to controlled blood pressure, we included participant-time starting at incident high blood pressure. Participants were included in this report at the first study visit since 2001 at which their systolic blood pressure (BP) was ≥140 or diastolic BP was ≥90 (henceforth the index visit), following a visit in which BP was controlled (i.e., systolic < 135 and diastolic < 85).

This study was approved by the University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board; data collection procedures are supervised by the Institutional Review Boards at each participating WIHS institution.

Ascertainment of BP.

Blood pressure measurements are taken using a standardized protocol: BP is measured after sitting for at least 5 minutes and at least 30 minutes after the intake of nicotine or caffeine. A second BP reading is taken after 1 minute, after elevation of the arm over the head for 5 seconds between readings; the two readings are then averaged to generate the blood pressure that is used in these analyses. Blood pressure was considered controlled if the systolic BP was <135 and the diastolic BP was <85.

Ascertainment of health insurance status, and covariates.

Insurance type was the primary exposure of interest, and was allowed to vary with time. Participants self-reported their insurance coverage at each study visit. Using a classification hierarchy similar to the one described in the Kaiser Issue Brief,9 we categorized insurance into four mutually exclusive categories. Insurance categories were assigned in this order: Medicaid or Medi-Cal, private insurance (including student health insurance), Medicare and other public insurance (including Tricare/CHAMPUS, Veteran’s Administration, and city or county coverage), and no health insurance. The text fields for those who reported other types of insurance were manually categorized into these groups as appropriate. There were only 52 participants who were categorized into the Medicare/other public insurance category, so we omitted those visits from analyses. Participants living with HIV also reported participation in ADAP, which may have been available to participants in any insurance category depending on state of residence and income.

Birthdate, race/ethnicity (categorized in this study as Hispanic, African American (non-Hispanic), White (non-Hispanic), or other), recruitment wave, and educational attainment (in categories of less than, equal to, or more than high school education) were collected at entry into the WIHS cohort. Body mass index (BMI) is calculated from measurements at each visit; CD4+ T lymphocyte counts and HIV-1 RNA levels (viral load) were measured at each visit for participants living with HIV. Annual household income and drug use in the past 6 months are self-reported at each visit. Participants were asked if they had seen a healthcare provider, and how often they had seen a healthcare provider over the past 6 months at study visits through September 2008, at which point the question was dropped from the questionnaire.

Statistical methods.

We counted person-time from elevated BP to the earliest of: blood pressure control (i.e., <135/85), drop-out (i.e., 1 year of missed visits), or 4 years (i.e., administrative censoring). The complement of the Kaplan–Meier survival curve estimator10 was used to estimate the cumulative risk of BP control. Risk differences were estimated by the difference in Kaplan–Meier estimates between the groups. Variance of the risk difference was calculated by summing the Greenwood variance estimates from both groups. The number of persons who would require insurance to reduce the uncontrolled blood pressure caseload by one case, or number needed to treat (NNT), was calculated as the reciprocal of the estimated risk difference.

Observed data were weighted by the product of stabilized inverse probability-of-exposure-and-censoring weights to account for confounding and selection bias by measured characteristics.11,12 Given a well-defined exposure or treatment, conditional exchangeability (i.e., no unmeasured confounding), and positivity (i.e., individuals in each strata defined by the exposure and covariates), and correct model specification our results provide a consistent estimate of the difference between risk functions.13 Health insurance type was modeled using pooled multinomial regression; censoring was modeled using pooled logistic regression. Models were fit for participants living with and without HIV infection separately.

For participants living with HIV confounders included age (using restricted quadratic splines (RQS) with knots at 40, 45, 49, and 53 years14), race/ethnicity (categorized as Hispanic, Black (non-Hispanic) and White (non-Hispanic), and other), study site, CD4+ cell count (lagged 6 months, using RQS with knots at 234, 362, 515, 705 cells/μl), HIV viral load (lagged 6 months, log transformed, using RQS with knots at 1.90, 1.90, 2.89, 4.17 log(copies/ml)), BMI (lagged 6 months, using RQS with knots at 23.2, 26.3, 30.1, 35.7 kg/m2), and previous health insurance status (lagged 6 and 12 months). Not included as confounders in the final weight model were illicit drug use and the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) as these variables did not alter the variance or final effect estimate. The resultant weights had a mean (SD) of 1.00 (0.53) and range of 0.03–14.87.

For HIV-uninfected participants confounders included age (using RQS with knots at 36, 42, 47, and 52 years14), race/ethnicity (categorized as Hispanic, Black (non-Hispanic) and White (non-Hispanic), and other), study site, BMI (lagged 6 months, using RQS with knots at 25.7, 29.1, 33.4, 39.6 kg/m2) and history of health insurance status (lagged 6 and 12 months). Not included as confounders in the final weight model were drug use and CES-D as these variables did not alter the variance or final effect estimate. The resultant weights had a mean (SD) of 1.00 (0.62) and ranged from 0.05 to 9.00.

Cox proportional hazards models were fit using PROC PHREG with a weight statement to incorporate the inverse probability of treatment and censoring weights. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics of the WIHS participants, 1,130 living with HIV and 415 HIV-uninfected, who had an elevated systolic or diastolic measurement are shown in Tables 1 and 2. A substantial proportion of all participants had Medicaid as their insurer (WLWH 68%, HIV-uninfected participants 57%); however, the proportion of uninsured participants was higher among HIV-uninfected women (n = 101, 24%) than WLWH (n = 127, 11%). The WIHS participants are low-income, and that is reflected in the high proportion (58% among WLWH and 53% among HIV-uninfected participants) who report yearly income below $12,000/year.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of HIV-infected participants at first observed blood pressure elevation

| No insurance (n = 127) | Medicaid (n = 772) | Private (n = 179) | Total (n = 1,130) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| On ADAP | 60 | 47.2 | 57 | 7.4 | 44 | 24.6 | 178 | 15.8 |

| No ART | 48 | 37.8 | 224 | 29.0 | 43 | 24.0 | 328 | 29.0 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| African-American | 78 | 61.4 | 529 | 68.5 | 94 | 52.5 | 726 | 64.2 |

| White | 8 | 6.3 | 64 | 8.3 | 52 | 29.1 | 134 | 11.9 |

| Hispanic | 38 | 29.9 | 159 | 20.6 | 23 | 12.8 | 236 | 20.9 |

| Other | 3 | 2.4 | 20 | 2.6 | 10 | 5.6 | 34 | 3.0 |

| ≥HS education | 67 | 52.8 | 440 | 57.0 | 160 | 89.4 | 706 | 62.5 |

| Income | ||||||||

| $0–$12,000 | 79 | 62.2 | 522 | 67.6 | 25 | 14.0 | 658 | 58.2 |

| $12,001–$30,000 | 35 | 27.6 | 198 | 25.6 | 41 | 22.9 | 291 | 25.8 |

| ≥$30,001 | 13 | 10.2 | 52 | 6.7 | 113 | 63.1 | 181 | 16.0 |

| Site | ||||||||

| Bronx | 5 | 3.9 | 192 | 24.9 | 13 | 7.3 | 214 | 18.9 |

| Brooklyn | 23 | 18.1 | 137 | 17.7 | 32 | 17.9 | 194 | 17.2 |

| Washington, DC | 20 | 15.7 | 88 | 11.4 | 49 | 27.4 | 170 | 15.0 |

| LA | 38 | 29.9 | 86 | 11.1 | 29 | 16.2 | 169 | 15.0 |

| San Francisco | 11 | 8.7 | 154 | 19.9 | 26 | 14.5 | 201 | 17.8 |

| Chicago | 30 | 23.6 | 115 | 14.9 | 30 | 16.8 | 182 | 16.1 |

| HDL ≤ 40 mg/dl | 46 | 36.2 | 221 | 28.6 | 169 | 94.4 | 310 | 27.4 |

| LDL ≥ 130 mg/dl | 24 | 18.9 | 134 | 17.4 | 50 | 27.9 | 208 | 18.4 |

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | |||||

| Age | 42 (37,47) | 46 (41, 51) | 45 (39, 52) | 46 (40, 51) | ||||

| CD4 cell count | 463 (294, 599) | 430 (251, 650) | 523 (336, 709) | 445 (274, 655) | ||||

| HIV viral load | 570 (80, 19,000) | 174 (80, 9,450) | 80 (80, 1,900) | 132 (80, 7,318) | ||||

| BMI | 29.4 (24.5, 36.5) | 28.5 (24.2, 34.2) | 27.8 (23.9, 33.0) | 28.3 (24.2, 34.0) | ||||

| Systolic BP at BS | 142 (135, 148) | 142 (136, 149) | 141 (134, 147) | 142 (136, 149) | ||||

| Diastolic BP at BS | 90 (82, 92) | 90 (84, 93) | 90 (80, 92) | 90 (83, 92) | ||||

| Waist circumference (cm) | 97.0 (84.5, 108.4) | 96.1 (83.2, 107.2) | 94.8 (82.6, 103.4) | 96.0 (83.2, 106.4) | ||||

BP elevation (≥140/90), when the BP at the prior visit was controlled (i.e., systolic <135 and diastolic <85).

Abbreviations: ADAP, AIDS Drug Assistance Program; ART, antiretroviral therapy; BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; BS, baseline; HDL, high density lipoprotein; HS, high school; IQR, interquartile range; LA, Los Angeles; LDL, low density lipoprotein.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of HIV-uninfected participants at first observed blood pressure elevation

| No insurance (n = 101) | Medicaid (n = 236) | Private (n = 78) | Total (n = 415) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| African-American | 70 | 69.3 | 158 | 66.9 | 57 | 73.1 | 285 | 68.7 |

| White | 5 | 5.0 | 16 | 6.8 | 9 | 11.5 | 30 | 7.2 |

| Hispanic | 24 | 23.8 | 51 | 21.6 | 10 | 12.8 | 85 | 20.5 |

| Other | 2 | 2.0 | 11 | 4.7 | 2 | 2.6 | 15 | 3.6 |

| ≥HS education | 61 | 60.4 | 140 | 59.3 | 68 | 87.2 | 269 | 64.8 |

| Income | ||||||||

| $0–$12,000 | 62 | 61.4 | 147 | 62.3 | 10 | 12.8 | 219 | 52.8 |

| $12,001–$30,000 | 27 | 26.7 | 77 | 32.6 | 27 | 34.6 | 131 | 31.6 |

| ≥$30,001 | 12 | 11.9 | 12 | 5.1 | 41 | 52.6 | 65 | 15.7 |

| Site | ||||||||

| Bronx | 14 | 13.9 | 85 | 36.0 | 18 | 23.1 | 117 | 28.2 |

| Brooklyn | 16 | 15.8 | 28 | 11.9 | 19 | 24.4 | 63 | 15.2 |

| Washington, DC | 12 | 11.9 | 25 | 10.6 | 16 | 20.5 | 53 | 12.8 |

| LA | 28 | 27.7 | 25 | 10.6 | 5 | 6.4 | 58 | 14.0 |

| San Francisco | 18 | 17.8 | 44 | 18.6 | 8 | 10.3 | 70 | 16.9 |

| Chicago | 13 | 12.9 | 29 | 12.3 | 12 | 15.4 | 54 | 13.0 |

| HDL ≤ 40 mg/dl | 13 | 12.9 | 35 | 14.8 | 17 | 21.8 | 65 | 15.7 |

| LDL ≥ 130 mg/dl | 24 | 23.8 | 45 | 19.1 | 18 | 23.1 | 87 | 21.0 |

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | |||||

| Age | 45 (37, 50) | 44 (37, 51) | 45 (37, 49) | 44 (37, 50) | ||||

| BMI | 27.9 (23.5, 33.4) | 31.7 (27.5, 38.8) | 33.9 (28.3, 39.2) | 31 (26, 38) | ||||

| Systolic BP at BS | 143 (140, 150) | 142 (140, 150) | 141 (140, 147) | 142 (136, 149) | ||||

| Diastolic BP at BS | 90 (83, 95) | 89 (81, 93) | 88 (81, 91) | 90 (83, 92) | ||||

| Waist circumference (cm) | 95.0 (80.3, 106.6) | 101.5 (87.4, 112.1) | 104.5 (94, 113.9) | 100.5 (86.6, 111.5) | ||||

BP elevation (≥140/90), when the BP at the prior visit was controlled (i.e., systolic <135 and diastolic <85).

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; BS, baseline; HDL, high density lipoprotein; HS, high school; IQR, interquartile range; LA, Los Angeles; LDL, low density lipoprotein.

Due to questionnaire changes, not all participants were asked about healthcare visits. Among the participants who were asked, 71% of women living without HIV infection (213/299) and 92% of women living with HIV infection (793/866) reported they had seen a healthcare provider in the past 6 months. The mean number of visits among those who had any healthcare visit was 4.3 among HIV-uninfected women and 5.1 among WLWH.

Among WLWH, uninsured participants were younger, had higher HIV viral load, were more likely to be Hispanic, and were more likely to be enrolled in ADAP. Given the small proportion of participants who were enrolled in ADAP in each insurance group (e.g., only 7.4% of Medicaid participants had ADAP), we were unable to stratify by ADAP participation. Privately insured participants had higher incomes and those who were uninsured or on Medicaid reported lower incomes. There were few other demographic differences between insurance groups among HIV-uninfected participants.

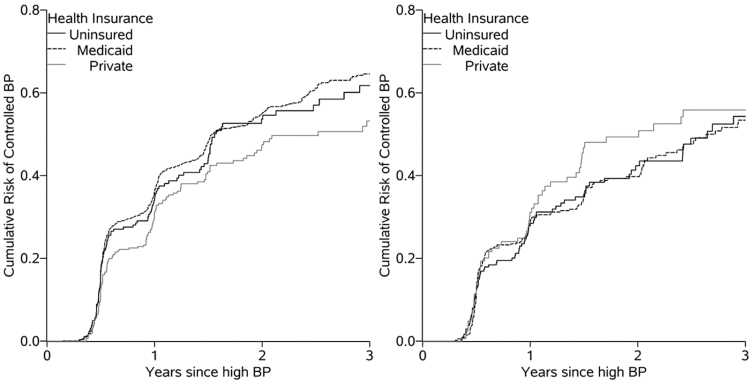

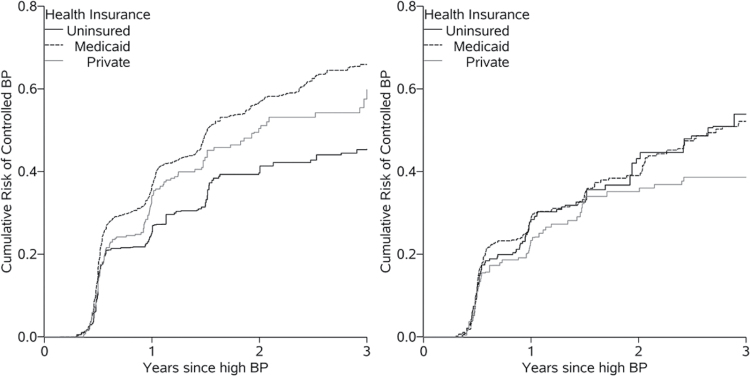

Crude and weighted curves of time to blood pressure control are presented in Figures 1 and 2. After accounting for age, CD4 cell count, race/ethnicity, BMI, HIV viral load, and study site, uninsured WLWH were the least likely to achieve a subsequent BP under 135/85 compared to both groups of insured WLWH. While all covariates contributed to adjusted estimates, weighting for age, a known predictor of both health insurance and blood pressure elevation, contributed the most to separating the uninsured group from the others. Among the HIV-uninfected participants after accounting for age, race/ethnicity, BMI, and study site, health insurance did not affect the proportion of participants who had a subsequent BP under 135/85.

Figure 1.

Time to control of blood pressure, after an elevated BP by health insurance status among women living with (left panel) and without (right panel) HIV.

Figure 2.

Weighted time to control of blood pressure, after an elevated BP by health insurance status among women living with (left panel, accounting for age, CD4 cell count, race/ethnicity, BMI, HIV viral load, and study site) and without (right panel, accounting for age, race/ethnicity, BMI, and study site) HIV.

In Table 3, we report the weighted cumulative risk of blood pressure control by 18 months after blood pressure elevation. As study visits are not clinical encounters for WIHS study participants, we chose 18 months as a reasonable amount of time for a participant to seek medical care in response to elevated blood pressure. The differences among the HIV-uninfected participants were minimal. However, among WLWH, comparing the uninsured to those with Medicaid yielded a risk difference of 0.16 (95% CI: 0.10, 0.23). This risk difference translates into a number needed to treat (i.e., insure) of 6. This means that to reduce the overall caseload of patients with uncontrolled blood pressure by one case, six uninsured participants would need to be insured via Medicaid.

Table 3.

Weighted cumulative risk of blood pressure control 18 months after elevation by health insurance status

| Risk | 95% CI | Risk difference | 95% CI | NNT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-infected participants | |||||

| Uninsured | 0.33 | 0.27, 0.39 | 0.16 | 0.10, 0.23 | 6 |

| Medicaid | 0.49 | 0.46, 0.52 | 0 | ||

| Private Insurance | 0.43 | 0.37, 0.49 | 0.06 | 0.00, 0.12 | 17 |

| HIV-uninfected participants | |||||

| Uninsured | 0.33 | 0.25, 0.39 | 0.02 | −0.06, 0.11 | 44 |

| Medicaid | 0.35 | 0.30, 0.39 | 0 | ||

| Private Insurance | 0.33 | 0.25, 0.41 | 0.02 | −0.08, 0.11 | 60 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; NNT, number needed to treat (i.e., insure).

We conducted two sensitivity analyses modifying the required high blood pressure measurement at entry: systolic BP ≥150 or diastolic BP ≥90, and two visits of systolic BP ≥140 or diastolic BP ≥90. Both of these sensitivity analyses did not substantially change the results (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

We examined in a predominantly low-income group the relationship between health insurance and control of hypertension among women living with HIV and a women with risk factors for HIV infection. We found that among WLWH, being uninsured was associated with less control of hypertension compared with women who were on Medicaid or were privately insured.

Among HIV-uninfected women, insurance did not convey the same benefits. This may be due to fewer health care visits among the HIV-uninfected women. Compared to WLWH, 21% fewer HIV-uninfected women saw a healthcare provider in the 6 months prior to their baseline visit. Even among those who visited a healthcare provider, HIV-uninfected women had a lower frequency of health care visits than the WLWH. Additionally, the number of HIV-uninfected individuals in each health insurance category was small, limiting the inference that can be drawn with precision.

Lower blood pressure control among uninsured WLWH in our study is consistent with results from the general population: uninsured individuals are least likely to have controlled blood pressure.3 Prior work in the WIHS cohort has shown that hypertension prevalence is similar between participants living with and without HIV.15 The authors identified increasing age, African-American race, BMI >30 kg/m as associated with increasing prevalence of hypertension, and pregnancy as protective. In an international, longitudinal HIV cohort, male sex, higher BMI, older age, higher BP at baseline, high total cholesterol and clinical lipodystrophy, and not antiretroviral drug class, have been associated with incident hypertension.16 However, our work suggests further research is needed to compare the amount of time individuals spend with uncontrolled hypertension—future studies may find that the increased contact with healthcare providers insured individuals living with HIV have leads to improved blood pressure control.

Guidelines about treatment of hypertension are in flux. This is due in part to the SPRINT trial, which showed a benefit among those at high cardiovascular risk to targeting blood pressure reduction strategies to <120/80 rather than the previously recommended target of <140/90.17 There is continuing discussion about best practices for individuals who are not at high cardiovascular risk. However, regardless of the health and longevity benefits to blood pressure control seen in randomized trials, access to health care and prescription medications remains a barrier to better blood pressure control on a population level.

There are some limitations to this report. First, participants may not have correctly self-reported their health insurance leading to potential exposure misclassification. However, studies have shown18–20 that those who self-reported no insurance are likely uninsured, supporting our conclusions about the WLWH who were uninsured. Second, as in all observational studies, we rely on the assumption of no unmeasured confounding. Given the difficulty of randomizing an exposure like health insurance, this analysis provides important information about the likely effects of health insurance on blood pressure using modern analytic methods. Third, the observation of an elevated BP at a WIHS visit is not necessarily associated with clinical follow up. Assuming that clinical follow up does result in lifestyle changes or prescription of anti-hypertension medication, the results from this analysis would underestimate the effect of insurance on hypertension control. Fourth, participants in the WIHS, a long-term cohort study, may differ from the population living with HIV in the United States, limiting generalizability. In comparison with clinic-based cohorts, however, the WIHS has the substantial advantage of including participants who are not linked to care.

There are a number of strengths to this study. WIHS data enables a longitudinal study design with a large study population. The retention for this cohort is high, and consequently there is minimal missing data. The data are managed by a central data processing center that checks for internal consistency and data quality. In addition, we used an analytic strategy that appropriately controls for time-varying confounding.

In conclusion, these results highlight the importance of health insurance for hypertension control.

Future directions

There have been a number of changes in the health care system resulting from the Affordable Care Act that have increased the number of insured individuals in the United States, including expansion of eligibility criteria for Medicaid. However, not all states have expanded Medicaid coverage, leaving a gap in health care access for the working poor.21 In addition, the future of the Affordable Care Act is uncertain. For the population living with HIV, our results suggest that the current coverage gap represents a missed opportunity for improving blood pressure control.

DISCLOSURE

All authors reported no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health [U01 AI103390 and K24 HD059358]. Data in this manuscript were collected by the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). WIHS (Principal Investigators): UAB-MS WIHS (Michael Saag, Mirjam-Colette Kempf, and Deborah Konkle-Parker), U01-AI-103401; Atlanta WIHS (Ighovwerha Ofotokun and Gina Wingood), U01-AI-103408; Bronx WIHS (Kathryn Anastos), U01-AI-035004; Brooklyn WIHS (Howard Minkoff and Deborah Gustafson), U01-AI-031834; Chicago WIHS (Mardge Cohen and Audrey French), U01-AI-034993; Metropolitan Washington WIHS (Mary Young and Seble Kassaye), U01-AI-034994; Miami WIHS (Margaret Fischl and Lisa Metsch), U01-AI-103397; UNC WIHS (Adaora Adimora), U01-AI-103390; Connie Wofsy Women’s HIV Study, Northern California (Ruth Greenblatt, Bradley Aouizerat, and Phyllis Tien), U01-AI-034989; WIHS Data Management and Analysis Center (Stephen Gange and Elizabeth Golub), U01-AI-042590; Southern California WIHS (Joel Milam), U01-HD-032632 (WIHS I–WIHS IV). The WIHS is funded primarily by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), with additional co-funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), and the National Institute on Mental Health (NIMH). Targeted supplemental funding for specific projects is also provided by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR), the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), the National Institute on Deafness and other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), and the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health. WIHS data collection is also supported by UL1-TR000004 (UCSF CTSA) and UL1-TR000454 (Atlanta CTSA).

REFERENCES

- 1. Marmot M, Friel S, Bell R, Houweling TA, Taylor S; Commission on Social Determinants of Health . Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Lancet 2008; 372:1661–1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kaiser Family Foundation. Medicaid/CHIP Eligibility. 2009. <http://facts.kff.org/chart.aspx?cb=56&sctn=151&ch=988>.

- 3. Duru OK, Vargas RB, Kermah D, Pan D, Norris KC. Health insurance status and hypertension monitoring and control in the United States. Am J Hypertens 2007; 20:348–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Oparil S. Women and hypertension: what did we learn from the Women’s Health Initiative? Cardiol Rev 2006; 14:267–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. National Alliance of State and Territorial AIDS Directors. 2015 ADAP Formulary Database: User’s Guide. 2016. <https://www.nastad.org/sites/default/files/2015-ADAP-Formulary-Database-Users-Guide-FINAL-December.pdf>.

- 6. Yi T, Cocohoba J, Cohen M, Anastos K, DeHovitz JA, Kono N, Hanna DB, Hessol NA. The impact of the AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP) on use of highly active antiretroviral and antihypertensive therapy among HIV-infected women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2011; 56:253–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Barkan SE, Melnick SL, Preston-Martin S, Weber K, Kalish LA, Miotti P, Young M, Greenblatt R, Sacks H, Feldman J. The Women’s Interagency HIV Study. WIHS Collaborative Study Group. Epidemiology 1998; 9:117–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hessol NA, Weber KM, Holman S, Robison E, Goparaju L, Alden CB, Kono N, Watts DH, Ameli N. Retention and attendance of women enrolled in a large prospective study of HIV-1 in the United States. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2009; 18:1627–1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kates J, Garfield R, Young K, Quinn K, Frazier E, Skarbinski J. Assessing the Impact of the Affordable Care Act on Health Insurance Coverage of People with HIV. 2014. <http://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/12/8535-assessing-the-impact-of-the-affordable-care-act-on-health-insurance-coverage.pdf>.

- 10. Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc 1958; 53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Robins JM, Hernán MA, Brumback B. Marginal structural models and causal inference in epidemiology. Epidemiology 2000; 11:550–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cole SR, Hernán MA. Constructing inverse probability weights for marginal structural models. Am J Epidemiol 2008; 168:656–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Robins JM, Hernan MA. Estimation of the causal effects of time-varying exposures. In Fitzmaurice G, Davidian M, Verbeke G, Molenberghs G (eds), Longitudinal Data Analysis. CRC Press: New York, 2009, pp. 553–599. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Howe CJ, Cole SR, Westreich DJ, Greenland S, Napravnik S, Eron JJ Jr. Splines for trend analysis and continuous confounder control. Epidemiology 2011; 22:874–875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Khalsa A, Karim R, Mack WJ, Minkoff H, Cohen M, Young M, Anastos K, Tien PC, Seaberg E, Levine AM. Correlates of prevalent hypertension in a large cohort of HIV-infected women: Women’s Interagency HIV Study. AIDS 2007; 21:2539–2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Thiébaut R, El-Sadr WM, Friis-Møller N, Rickenbach M, Reiss P, Monforte AD, Morfeldt L, Fontas E, Kirk O, De Wit S, Calvo G, Law MG, Dabis F, Sabin CA, Lundgren JD; Data Collection of Adverse events of anti-HIV Drugs Study Group . Predictors of hypertension and changes of blood pressure in HIV-infected patients. Antivir Ther 2005; 10:811–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Group SR, Wright JT Jr, Williamson JD, Whelton PK, Snyder JK, Sink KM, Rocco MV, Reboussin DM, Rahman M, Oparil S, Lewis CE, Kimmel PL, Johnson KC, Goff DC Jr, Fine LJ, Cutler JA, Cushman WC, Cheung AK, Ambrosius WT; SPRINT Research Group . A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:2103–2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Call KT, Davidson G, Davern M, Nyman R. Medicaid undercount and bias to estimates of uninsurance: new estimates and existing evidence. Health Serv Res 2008; 43:901–914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kincheloe J, Brown ER, Frates J, Call KT, Yen W, Watkins J. Can we trust population surveys to count Medicaid enrollees and the uninsured? Health Aff (Millwood) 2006; 25:1163–1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Davern M, Quinn BC, Kenney GM, Blewett LA. The American Community Survey and health insurance coverage estimates: possibilities and challenges for health policy researchers. Health Serv Res 2009; 44:593–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Walters E. Insurance changes raise concerns for HIV patients. New York Times 7 December 2013. [Google Scholar]