Abstract

Background

This study addresses whether the association of adiponectin gene (ADIPOQ) variants with idiopathic recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL) is influenced by obesity.

Methods

Retrospective case–control study performed in outpatient obstetrics/gynecology clinics. Study subjects comprised 308 women with RPL, defined as ≥ 3 consecutive miscarriages of unknown etiology, and 310 control women. ADIPOQ genotyping was done by allele exclusion method on real-time PCR.

Results

Of the 14 ADIPOQ variants tested, the minor allele frequency (MAF) of rs4632532, rs17300539, rs266729, rs182052, rs16861209, and rs7649121 were significantly higher, while rs2241767, and rs1063539 MAF were lower in RPL cases, hence assigning RPL-susceptibility and protection to these variants, respectively. Higher frequencies of heterozygous rs17300539 and rs16861209, and homozygous rs4632532, rs266729, and rs182052 genotypes, and reduced frequencies of heterozygous rs1063539 and rs2241767, homozygous rs2241766 genotypes were seen in RPL cases. ADIPOQ rs4632532, and rs2241766 were associated with RPL in obese, while rs1063539 and rs16861209 were associated with RPL in non-obese women; rs182052 and rs7649121 associated with RPL independently of BMI changes. Based on LD pattern, two haplotype blocks were identified. Within Block 1 containing rs4632532, rs16861194, rs17300539, rs266729, rs182052, rs16861209, rs822396, and rs7649121, increased frequency of CAGGACAT and TAACGAAA, and reduced frequency of TAGCGCAA haplotypes were seen in RPL cases when compared to controls, thereby assigning RPL susceptibility and protection, respectively.

Conclusion

This is the first study to document contribution of ADIPOQ variants and haplotypes with RPL, and also to underscore the contribution of obesity to genetic association studies.

Keywords: Adiponectin, Haplotypes, Idiopathic recurrent miscarriage, Real-time PCR

Background

Recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL), defined as ≥ 2 idiopathic miscarriages with the same partner prior the 20th week of gestation [1], is a common pregnancy complication which affects ~ 1–2% of women worldwide [2]. Modifiable and non-modifiable factors that contribute to RPL pathogenesis were reported. The former includes environmental and lifestyle factors (smoking, obesity), poorly-controlled diabetes, hypothyroidism, and infections [3, 4], while the latter includes chromosomal anomalies, age at first pregnancy, and presence of specific genetic polymorphisms [2, 5]. Despite the identification of several risk factors of RPL, the etiology of idiopathic RPL remains not completely understood, with more than 50% of RPL cases still remain unexplained [1, 2].

Normal human pregnancy is linked with altered metabolism stemming from the accumulation of white adipose tissues [6], leading to progressive decrease in insulin sensitivity [6, 7]. White adipose tissues synthetize an array of hormones within the intra-uterine compartment, which serve both metabolic, anti-atherosclerotic, and anti-inflammatory roles. These include leptin, resistin, apelin, and adiponectin [8]. Adiponectin is a 30 kDa, 244 amino acid adipokine, which regulates insulin sensitivity, blood glucose levels, and lipid metabolism, and possesses anti-atherosclerosis and anti-inflammatory activities [9].

Adiponectin is produced mostly from adipocyte, but is also secreted by other tissues, including reproductive organs [9]. Adiponectin is detected in amniotic fluid after 15 weeks of pregnancy, and its maternal plasma concentrations remain virtually unchanged throughout pregnancy [10, 11]. Reduction in adiponectin levels results in reproductive disorders [12, 13], including failed embryo implantation, polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), endometriosis, gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) [14, 15], and RPL [16]. Adiponectin is encoded by ADIPOQ gene (adipocyte C1Q and collagen domain), located on chromosome 3q27 spanning 17 kB, and containing 3 exons and two introns [17], and is highly polymorphic. Previous studies demonstrated association of functional ADIPOQ gene variants with altered circulating adiponectin concentrations [18, 19], and with pregnancy complications, including GDM, metabolic syndrome, and preeclampsia (PE) [20–22]. Decreased adiponectin serum levels were also linked with severe obesity [23], endometriosis and PCOS [12].

Very few studies examined the association of ADIPOQ variants with idiopathic RPL. An earlier Indian study documented the association of ADIPOQ rs2241766 (exon 2) and rs15012299 (intron 2) with increased risk of RPL [16]. In addition, ADIPOQ rs2241766 and rs15012299 variants showed weak, but statistically significant, haplotype association with PE susceptibility in Finnish women [24]. Here we analyze the association of 14 common ADIPOQ variants in women with confirmed RPL diagnosis, and multiparous control women who were matched to RPL cases according to self-declared racial background. The contribution of these variants to RPL was examined according to obesity, and was examined at the allele, genotype, and haplotype levels.

Subjects and methods

Subjects

This retrospective case–control study was performed between January 2013 and June 2015. Study population included 308 women with confirmed RPL who were recruited consecutively from the outpatient OB/GYN clinics in Manama and Riffa (Bahrain). In addition, we recruited 310 multiparous women with two or more successful pregnancies as controls. The study protocol was approved by Arabian Gulf University Research and Ethics Committee (IRB approval: 35-PI-01/15), and was done according to Helsinki II Declaration. All patients provided informed written consent before blood sampling.

We defined RPL as ≥ 3 consecutive pregnancy losses of undetermined etiology, which occurred between the 7th–20th week of gestation, and with the same partner. RPL assessment was according to the guidelines of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (https://www.rcog.org.uk/guidelines). These required screening for LAC (lupus anticoagulant) and ACL (anticardiolipin) anti-phospholipid antibodies, and the inherited thrombophilias Factor V-Leiden (R506Q) and factor II/prothrombin G20210A. Karyotyping of both parents, and pelvic ultrasound scan by hysteroscopy or sonohysteroscopy for evaluation of uterine anatomy were also performed on all RPL cases. RPL cases were excluded if they were 40 years or older at first pregnancy, incompatibility in Rh blood groups, history of PE, which was defined as elevation in systolic/diastolic blood pressure (BP) exceeding 145/95 mmHg, or increase in systolic/diastolic BP exceeding 30/15 mmHg on at least two occasions, as well as biochemical pregnancy, and preclinical miscarriages. Cases were also excluded if they had systemic autoimmunity, thyroid dysfunction, diabetes, liver function abnormalities, anatomical disorders, and infections (toxoplasmosis, HIV, HCMV, Group B streptococci, Chlamydia trachomatis, hepatitis B and C viruses, rubella, and bacterial vaginosis).

Control women comprised hospital and university students and employees, and volunteers from the community, and were included if they had two or more successful pregnancies. Control women were included following check-up after uncomplicated pregnancy/delivery. Controls were excluded if they reported spontaneous and/or induced miscarriages, and family history of miscarriage, and were matched to RPL cases according to age (P = 0.94), and self-reported ethnic origin (all Bahraini Arabs). Peripheral blood samples (2–5 ml) were collected from RPL cases and control women in EDTA-containing tubes for DNA extraction.

ADIPOQ genotyping

ADIPOQ single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) with minor allele frequencies (MAF) that exceeded 5% in Caucasians (HapMap CEU), were selected using SNPbrowser software 4.0 (ABI-ThermoFisher, Foster City, CA). Genotyping was done by the allelic discrimination method using VIC-/FAM-labelled primers (Table 2). Assay-on-demand TaqMan assays were obtained from ABI-ThermoFisher. PCR was performed in 6 μl volume on StepOne Plus real-time PCR system, according to instructions of the manufacturer (ABI-ThermoFisher). A typical RT-PCR consisted of adding 2.2 µl DNA template, and 4.0 µl TaqMan genotype master mix (TaqMan 2X mix, 1.875 µl nuclease free water, and 0.125 µl 40X SNP primer mix) (Applied Biosystem). Pre-PCR (hold step) stage was performed for 30 s at 60 °C, and for 10 min at 95 °C. The cycles conditions will be repeated 35 times, and consisted of denaturation (92 °C for 15 s), annealing and extension (60 °C for 1 min), followed by post-PCR stage at 60 °C for 30 s. Replicate quality control samples (≈ 10% of cases and controls) were included for assessment of genotyping reproducibility; concordance consistently exceeded 99%.

Table 2.

ADIPOQ SNPs analyzed in RPL cases and control women

| SNP | Assay ID | Position | HWE P | Alleles | Casesa | Controlsa | χ2 | P | aORb (95% CI) | Power |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs4632532 | C_27867233_10 | 186551682 | 0.209 | T:C | 0.351 | 0.271 | 7.035 | 0.008 | 1.46 (1.10–1.93) | 90 |

| rs16861194 | C_33187775_10 | 186559425 | 0.325 | A:G | 0.098 | 0.079 | 0.979 | 0.322 | 1.25 (0.80–1.95) | 63 |

| rs17300539 | C_33187774_10 | 186559460 | 1.000 | G:A | 0.087 | 0.044 | 6.534 | 0.011 | 2.06 (1.17–3.63) | 100 |

| rs266729 | C_2412786_10 | 186559474 | 0.213 | C:G | 0.262 | 0.173 | 8.295 | 0.004 | 1.69 (1.18–2.42) | 83 |

| rs182052 | C_2412785_10 | 186560782 | 0.348 | G:A | 0.360 | 0.249 | 11.381 | 7.00 × 10 −4 | 1.70 (1.25–2.31) | 100 |

| rs16861209 | C_33187764_10 | 186563114 | 0.205 | C:A | 0.144 | 0.087 | 6.852 | 0.009 | 1.77 (1.15–2.72) | 89 |

| rs822396 | C_2910316_10 | 186566877 | 0.337 | A:G | 0.139 | 0.157 | 0.582 | 0.445 | 0.92 (0.64–1.33) | 42 |

| rs7649121 | C_42772949_10 | 186568785 | 0.303 | A:T | 0.182 | 0.134 | 4.063 | 0.044 | 1.44 (1.01–2.05) | |

| rs2241766 | C_26426077_10 | 186570892 | 0.578 | T:G | 0.156 | 0.193 | 2.166 | 0.141 | 0.80 (0.57–1.12) | 62 |

| rs1501299 | C_7497299_10 | 186571123 | 0.212 | C:A | 0.324 | 0.307 | 0.343 | 0.558 | 1.09 (0.83–1.43) | 54 |

| rs2241767 | C_26426076_10 | 186571196 | 1.000 | A:G | 0.139 | 0.188 | 4.161 | 0.041 | 0.70 (0.49–0.98) | 66 |

| rs3774261 | C_27479710_10 | 186571559 | 0.303 | G:A | 0.462 | 0.495 | 0.989 | 0.320 | 0.87 (0.67–1.14) | 61 |

| rs6773957 | C_1486294_10 | 186573705 | 0.285 | G:A | 0.506 | 0.475 | 0.951 | 0.330 | 1.13 (0.88–1.46) | 63 |

| rs1063539 | C_1486290_10 | 186575392 | 0.277 | G:C | 0.147 | 0.196 | 3.898 | 0.048 | 0.70 (0.50–0.99) | 68 |

Italicface indicates statistical significance

aMAF frequency

baOR = adjusted OR; variables that were controlled for were BMI, menarche, systolic and diastolic blood pressure

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was done on SPSS v. 24 (IBM, Armonk, NY). Categorical variables were expressed as percent of total, while continuous data were presented as mean ± SD. Differences in means were analyzed using Student’s t test, and inter–group significance was assessed by Pearson χ2 or Fisher’s exact test. Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) calculation was done for control women using Haploview 4.2 (https://www.broad.mit.edu/mpg/haploview). SNPStats (https://bioinfo.iconcologia.net/snpstats) was used for genetic association analysis, under the assumption of additive genetic model. Power calculation for detection of association between ADIPOQ variants and RPL was done using CaTS Power Calculator (https://www.sph.umich.edu/csg/abecasis/cats). We used the following parameters: 308 RPL cases and 310 control women, relative risk for heterozygous and minor allele homozygous genotypes, and MAF for the 14 tested ADIPOQ SNPs RPL in cases and controls, and assuming a 2.5% population RPL prevalence in Bahrain (Bahrain Ministry of Health unpublished statistics). The overall power was calculated as 72.1%, which represented the average power of the included SNPs. Haploview 4.2 was used for determination of linkage disequilibrium (LD) and haplotype reconstruction, the latter done according to expectation maximization (EM) algorithm. Taking control women as the reference group, logistic regression analysis was used in determining odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) associated with the risk of RPL; P < 0.05 was taken as statistically significant.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics of RPL cases and control women

Table 1 summarizes the demographic and clinical profiles of RPL cases and control women. Age at entry into the study, fasting plasma glucose, gravida, and number of smokers were not significantly different between women with RPL and control subjects. Significant differences between the two study groups were seen in mean BMI (P = 0.004), menarche (P < 0.001), and in systolic/diastolic blood pressure readings (P < 0.001). While these did not constitute established RPL risk factors, we nevertheless included them as covariates which we controlled for in later analysis.

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristics of cases and controls

| Casesa | Controlsa | P b | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at inclusion in studyc | 31.6 ± 5.4 | 31.6 ± 4.9 | 0.94 |

| Body-mass index (kg/m2)c | 26.3 ± 5.4 | 25.2 ± 4.3 | 0.004 |

| Obesity [n (%)]d | 58 (19.6) | 37 (12.1) | 0.02 |

| Smokers [n (%)]d | 30 (10.1) | 32 (10.8) | 0.69 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg)c | 114.2 ± 11.9 | 120.2 ± 17.0 | < 0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg)c | 72.0 ± 8.4 | 75.8 ± 9.1 | < 0.001 |

| Glucose (mmol/L)c | 5.1 ± 0.9 | 5.2 ± 0.7 | 0.55 |

| Menarche (years)c | 12.2 ± 1.1 | 12.8 ± 1.0 | < 0.001 |

| Number of pregnanciesc | 4.2 ± 1.5 | 4.0 ± 1.1 | 0.11 |

| Number of childrenc | 0.8 ± 1.1 | 4.0 ± 1.1 | < 0.001 |

| Miscarriagesc | 3.6 ± 1.0 | 0.0 ± 0.1 | < 0.001 |

aA total of 308 RPL cases and 310 control women were included

bStudent’s t-test (continuous variables), Pearson’s χ2 test (categorical variables)

cMean ± SD

dPercent of total within each group/subgroup

Association between ADIPOQ SNP and the risk of RPL

Table 2 presents the association between ADIPOQ SNP and RPL in women with RPL and control women. Genotype distributions of all 14 tested ADIPOQ variants conformed to HWE among study subjects. Among ADIPOQ SNP tested, higher MAF of rs4632532 (P = 8.00 × 10−3), rs17300539 (P = 0.011), rs266729 (P = 4.00 × 10−3), rs182052 (P = 7.00 × 10−4), rs16861209 (P = 9.00 × 10−3), rs7649121 (P = 0.044), thereby assigning RPL susceptibility to these variants. On the other hand, MAF of rs2241767 (P = 0.041) and rs1063539 (P = 0.048), was lower in women with RPL than in control women, suggesting RPL-protection associated with these ADIPOQ variants. No significant differences in MAF of the remaining SNPs were seen between women with RPL and controls.

Table 3 lists the distribution of ADIPOQ genotypes between women with RPL and control women. Taking major allele homozygous genotype (1/1) as the reference group (OR = 1.00), after controlling for BMI, systolic/diastolic blood pressure, and menarche, significantly higher frequencies of heterozygous rs17300539 (0.17 vs. 0.08) and rs16861209 (0.32 vs. 0.15), and homozygous rs4632532 (0.13 vs. 0.08), rs266729 (0.11 vs. 0.05), and rs182052 (0.16 vs. 0.05) genotypes were seen in RPL cases vs. control women. In addition, reduced genotype frequencies of heterozygous rs1063539 (0.21 vs. 0.31) and rs2241767 (0.22 vs. 0.31), and homozygous rs2241766 (0.02 vs. 0.07) were seen in women with RPL compared to controls. The distribution of the remaining genotypes was not significantly different between women with RPL and control subjects.

Table 3.

ADIPOQ genotype frequencies

| SNP | 1/1a | 1/2a | 2/2a | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Controls | P b | Cases | Controls | OR (95% CI) | Cases | Controls | OR (95% CI) | |

| rs4632532 | 141 (0.46)c | 171 (0.55) | 0.042 | 126 (0.41) | 114 (0.37) | 1.33 (0.92–1.93) | 41 (0.13) | 25 (0.08) | 2.03 (1.11–3.70) |

| rs1063539 | 229 (0.74) | 199 (0.64) | 0.060 | 68 (0.21) | 95 (0.31) | 0.63 (0.41–0.96) | 11 (0.04) | 16 (0.05) | 0.57 (0.23–1.44) |

| rs17300539 | 256 (0.83) | 283 (0.91) | 0.027 | 51 (0.17) | 25 (0.08) | 2.22 (1.22–4.04) | 1 (0.003) | 1 (0.003) | 1.08 (0.07–17.41) |

| rs16861209 | 229 (0.74) | 259 (0.84) | 0.032 | 69 (0.32) | 48 (0.15) | 1.64 (1.01–2.68) | 10 (0.03) | 3 (0.01) | 3.87 (0.79–18.88) |

| rs266729 | 187 (0.61) | 208 (0.67) | 0.079 | 88 (0.29) | 86 (0.28) | 1.14 (0.74–1.77) | 33 (0.11) | 16 (0.05) | 2.37 (1.09–5.18) |

| rs822396 | 233 (0.76) | 223 (0.72) | 0.650 | 66 (0.21) | 78 (0.25) | 0.81 (0.53–1.25) | 9 (0.03) | 9 (0.03) | 0.96 (0.33–2.80) |

| rs1501299 | 144 (0.47) | 161 (0.52) | 0.511 | 127 (0.41) | 115 (0.37) | 1.23 (0.85–1.79) | 37 (0.12) | 34 (0.11) | 1.23 (0.69–2.17) |

| rs182052 | 132 (0.43) | 174 (0.56) | 0.001 | 128 (0.42) | 119 (0.38) | 1.43 (0.94–2.17) | 48 (0.16) | 17 (0.05) | 3.67 (1.73–7.76) |

| rs7649121 | 222 (0.72) | 244 (0.79) | 0.190 | 57 (0.19) | 49 (0.16) | 1.30 (0.80–2.10) | 29 (0.09) | 17 (0.05) | 1.76 (0.86–3.58) |

| rs2241766 | 219 (0.71) | 195 (0.63) | 0.043 | 82 (0.27) | 96 (0.31) | 0.77 (0.52–1.13) | 7 (0.02) | 22 (0.07) | 0.34 (0.13–0.90) |

| rs3774261 | 92 (0.30) | 93 (0.30) | 0.212 | 148 (0.48) | 127 (0.41) | 1.19 (0.76–1.86) | 68 (0.22) | 90 (0.29) | 0.78 (0.47–1.30) |

| rs16861194 | 257 (0.83) | 264 (0.85) | 0.687 | 46 (0.15) | 44 (0.14) | 1.09 (0.67–1.76) | 5 (0.02) | 2 (0.01) | 2.01 (0.36–11.08) |

| rs6773957 | 80 (0.26) | 88 (0.28) | 0.790 | 144 (0.47) | 144 (0.46) | 1.11 (0.73–1.69) | 84 (0.27) | 78 (0.25) | 1.18 (0.73–1.90) |

| rs2241767 | 223 (0.72) | 200 (0.65) | 0.054 | 67 (0.22) | 96 (0.31) | 0.62 (0.42–0.93) | 18 (0.06) | 14 (0.05) | 1.14 (0.51–2.56) |

Italicface indicates statistical significance

aGenotypes were coded as per “1” = major allele, “2” = minor allele

b2-way ANOVA

cNumber of subjects (frequency)

Association of ADIPOQ polymorphisms with RPL in obese and non-obese RPL subjects

In view of the effect of ADIPOQ SNPs on adiponectin secretion, and the impact of adiposity of pregnancy outcome, we examined the association of the tested ADIPOQ polymorphisms with RPL in obese and non-obese RPL cases and controls. Women with RPL and control women were sub grouped into non-obese and obese according to BMI cutoff of 30 kg/m2. Results from Table 4 demonstrate differential association of ADIPOQ SNPs with RPL according to obesity was seen, with rs16861209 (P = 0.034), rs182052 (P = 0.004), and rs7649121 (P = 0.040) being positively associated, while rs1063539 (P = 0.028) was negatively associated with RPL in obese subjects (Table 3). In contrast, rs182052 (P = 0.005), and rs7649121 (P = 0.046) were positively, while rs4632532 (P = 0.002), and rs2241766 (P = 0.021) were negatively associated with RPL in obese subjects.

Table 4.

Association of ADIPOQ variants with RPL in obese vs. non-obese cases and control women

| SNP | Non-obese | Obese | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controla | Casea | P | OR (95% CI) | Controla | Casea | P | OR (95% CI) | |

| rs4632532 | 28.05 | 33.33 | 0.093 | 1.28 (0.96–1.71) | 12.00 | 36.17 | 0.002 | 4.15 (1.60–10.76) |

| rs1063539 | 20.45 | 14.40 | 0.028 | 0.65 (0.44–0.95) | 23.08 | 15.85 | 0.296 | 0.63 (0.26–1.51) |

| rs17300539 | 03.72 | 06.91 | 0.053 | 1.92 (0.98–3.75) | 09.26 | 17.11 | 0.202 | 2.02 (0.68–6.06) |

| rs16861209 | 07.88 | 12.64 | 0.034 | 1.69 (1.03–2.76) | 13.46 | 23.68 | 0.152 | 1.99 (0.77–5.19) |

| rs266729 | 19.17 | 24.00 | 0.117 | 1.33 (0.93–1.91) | 16.67 | 30.26 | 0.125 | 2.17 (0.79–5.92) |

| rs822396 | 16.09 | 14.89 | 0.647 | 0.91 (0.62–1.35) | 13.79 | 08.75 | 0.348 | 0.60 (0.20–1.76) |

| rs1501299 | 29.01 | 31.86 | 0.371 | 1.14 (.085–1.54) | 32.14 | 35.56 | 0.671 | 1.16 (0.57–2.36) |

| rs182052 | 26.90 | 37.50 | 0.004 | 1.63 (1.17–2.27) | 10.71 | 31.43 | 0.005 | 3.82 (1.42–10.24) |

| rs7649121 | 13.78 | 19.19 | 0.040 | 1.49 (1.02–2.18) | 10.71 | 26.09 | 0.046 | 2.60 (0.99–6.80) |

| rs2241766 | 20.62 | 16.09 | 0.093 | 0.74 (0.52–1.05) | 30.00 | 14.44 | 0.021 | 0.39 (0.18–0.88) |

| rs3774261 | 32.08 | 45.45 | 0.386 | 0.88 (0.65–1.18) | 46.00 | 48.68 | 0.764 | 1.11 (0.54–2.28) |

| rs16861194 | 08.63 | 09.05 | 0.823 | 1.05 (0.66–1.68) | 00.00 | 07.45 | – | N/A |

| rs6773957 | 49.53 | 51.50 | 0.571 | 1.08 (0.82–1.42) | 41.38 | 46.94 | 0.498 | 1.25 (0.65–2.42) |

| rs2241767 | 19.82 | 15.79 | 0.125 | 0.76 (0.53–1.08) | 24.14 | 19.39 | 0.484 | 0.76 (0.35–1.65) |

Italicface indicates statistical significance

aPercent minor allele carriers

Identification of ADIPOQ haplotypes associated with RPL

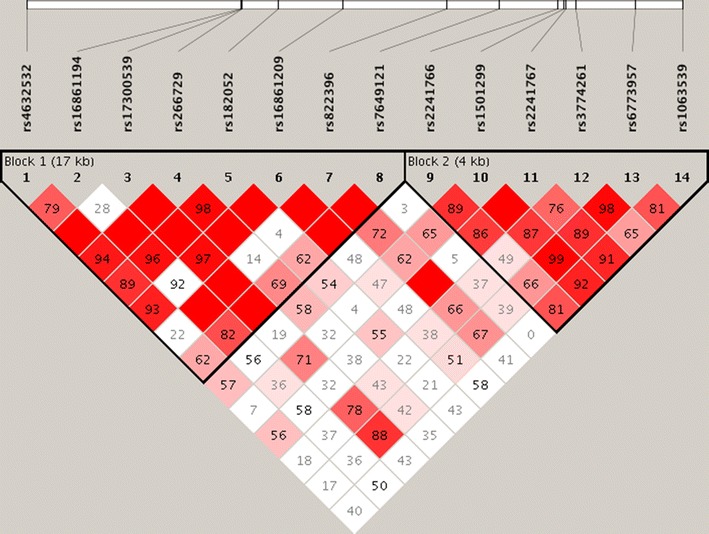

The interaction between tested ADIPOQ variants, and their mode of inheritance in women with RPL and control women was next evaluated. The interaction between pair of SNP visualized by Haploview (Fig. 1). Haploview analysis showed marked LD among the tested ADIPOQ variants (Fig. 1), and defined two haploblocks. Haploblock 1 spanned 17 kb, and contained rs4632532, rs16861194, rs17300539, rs266729, rs182052, rs16861209, rs822396, and rs7649121, while Haploblock 2 spanned 4 kb, and contained rs2241766, rs1501299, rs2241767, rs3774261, rs6773957, and rs1063539.

Fig. 1.

Haploview plot of ADIPOQ SNP analyzed. The relative positions of ADIPOQ SNPs (Build 37.3) are displayed, along with the basic gene structure, above the Haploview diagram. The relative LD between pairs of ADIPOQ SNPs is color-indicated. This was based on D’, i.e. normalized linkage disequilibrium measure or D divided by the theoretical maximum for the observed allele frequencies, multiplied by 100. Values close to zero indicate no LD, while values approaching 100 indicate full LD. The red colored square represents varying degrees of LD < 1 and LOD (logarithm of odds) > 2 scores; darker shades indicating stronger LD

“Common haplotype” was defined as the haplotype with frequencies > 2% of the total haplotypes. Within Haploblock 1, 94.8% of 8-locus haplotype diversity was captured by 9 of the possible 256 haplotypes. Higher frequencies of CAGGACAT (P = 5.1 × 10−3) and TAACGAAA (P = 0.012), and reduced frequency of TAGCGCAA (P = 7.6 × 10−5) haplotypes were seen in RPL cases, suggesting RPL-susceptible and RPL-protective aspect of these haplotypes, respectively. The frequencies of remaining haplotypes in Haploblock 1, and all haplotypes in Haploblock 2 were comparable between women with RPL and control women (Table 5).

Table 5.

Haplotype frequencies across 14 ADIPOQ SNPs analyzeda

| Haplotypeb | Frequency | Case:control frequency | χ2 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Block 1 | T A G C G C A A | 0.433 | 0.369; 0.499 | 15.64 | 7.6 × 10−5 |

| C A G G A C A T | 0.120 | 0.149; 0.089 | 7.86 | 5.1 × 10−3 | |

| T A G C G C G A | 0.086 | 0.082; 0.091 | 0.19 | 0.661 | |

| C G G C A C A A | 0.068 | 0.076; 0.059 | 1.01 | 0.314 | |

| T A A C G A A A | 0.067 | 0.087; 0.046 | 6.27 | 0.012 | |

| C A G G A C G A | 0.048 | 0.053; 0.043 | 0.52 | 0.471 | |

| T A G C G A A A | 0.046 | 0.054; 0.038 | 1.23 | 0.268 | |

| C A G G A C A A | 0.042 | 0.051; 0.032 | 2.14 | 0.144 | |

| T A G C G C A T | 0.038 | 0.037; 0.040 | 0.04 | 0.837 | |

| Block 2 | T C A G A G | 0.445 | 0.475; 0.414 | 3.71 | 0.054 |

| T A A A G G | 0.291 | 0.295; 0.287 | 0.06 | 0.801 | |

| G C G A G C | 0.125 | 0.119; 0.132 | 0.36 | 0.546 | |

| T C A A G G | 0.029 | 0.023; 0.035 | 1.40 | 0.236 | |

| G C A G A G | 0.021 | 0.015; 0.026 | 1.43 | 0.231 | |

Italicface indicates statistical significance

aADIPOQ Block 1: rs4632532- rs16861194- rs17300539- rs266729- rs182052- rs16861209- rs822396- rs7649121, Block 2: rs2241766- rs1501299- rs2241767- rs3774261- rs6773957- rs1063539 haplotypes

bUnderlined indicates minor allele

Discussion

Overview of the association of ADIPOQ SNPs with RPL

ADIPOQ is a highly polymorphic gene (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/9370), and 2376 variants were identified, some of which modulate circulating adiponectin concentrations [18, 23, 25]. We investigated the association between RPL and variants in the intergenic, 5′-near gene, promoter, introns, exons, and 3′-UTR regions of ADIPOQ gene. Among the 14 tested variants, significant association with RPL risk was seen with intergenic (rs4632532), intronic (rs7649121, rs2241767), and exonic (rs2241766, rs1501299) ADIPOQ variants. This is the first report that identified these ADIPOQ variants as RPL at-risk loci, further supporting a role for adiponectin in the pathogenesis of RPL.

Significance of the findings

The association between (exonic) rs1501299 (+ 276G > T) and RPL seen here was in apparent disagreement with a study on North Indian women, which reported marginal association of the + 276G > T variant (P = 0.0360) with reduced risk of RPL [16]. This discrepancy is likely attributed to differences in ethnic background of study participants, study selection criteria and genotyping conditions. The rs1501299 (+ 276G > T) variant was associated with altered adiponectin serum levels [26], and with hypertensive disorder complicating pregnancy (HDCP) in Chinese subjects [27].

In addition to rs1501299, rs266729 was associated with GDM in Polish [22] and Bulgarian [20], but not Brazilian women [21]; its minor (G) allele conferring protection against GDM [20]. Functionally, rs266729 was linked with altered adiponectin levels in Caucasians [17, 28], which was attributed to the capacity of its minor (G) allele to destroy Sp1 transcription factor DNA binding in the ADIPOQ promoter region [29].

ADIPOQ rs7649121 was linked with reduced risk of coronary heart disease in Chinese [30]. In addition, r rs17300539 was reportedly associated with reduced adiponectin levels in white women [31], and in T2DM patients [32]. Our study is the first to demonstrate positive association between rs7649121 and rs17300539 and RPL. On the other hand, rs2241767 was negatively associated with RPL in our cohort. This variant was associated with T2DM in Tunisian Arabs [33], and with insulin resistance in Mexican Americans [34].

ADIPOQ rs2241766 variant is present in exon 2, and its functional attributes are not understood, although it does not alteration of target amino acid sequence. It was reported that the carriage of rs2241766 is associated with altered mRNA splicing and/or stability [26]. While a number of studies documented association of (exonic) rs2241766 variant with pregnancy complications [21, 35], including PCOS in Brazilian [21], but not Chinese [36] women, it was not associated with RPL in our cohort. This was in agreement with the earlier study on non-obese North Indian women [16], which documented lack of association of rs2241766 with RPL.

Obesity as risk factor of RPL: adiponectin connection

Obesity is a major contributor to infertility, and is associated with reduced success of assisted reproductive technologies [4, 37]. Given the association of reduced adiponectin to obesity and insulin resistance, a role for adiponectin in promoting successful pregnancy was suggested [14, 15]. There is a solid link between adiposity, obesity, insulin resistance and RPL [38]. Obesity was consistently associated with conditions linked with poor pregnancy outcome, including idiopathic RPL [3, 38].

Adiponectin was proposed to constitute an at-risk modulator of RPL. An earlier systematic review involving 24,738 women, concluded that obesity increases the risk of sporadic miscarriage [37], and was attributed to reduced adiponectin secretion [39, 40]. By controlling steroidogenesis and expression of genes involved in ovulation [13, 41], and induction of metabolic changes linked with adipose tissues dysfunction, particularly in genetically predisposed women [42], a central role of adiponectin in pregnancy outcome was established. In our hands, RPL-susceptible and—protective ADIPO SNP and haplotypes were identified, when unselected RPL cases were compared to control women, and also when RPL cases were stratified according to obesity.

Furthermore, we demonstrated that rs16861209, rs182052, and rs7649121 amplify RPL risk in non-obese women. This was in contrast to rs1063539 which was negatively associated with RPL, and presumably having a protective effect on pregnancy. On the other side, in obese subjects, rs4632532, rs182052, and rs7649121 were linked with increased RPL susceptibility, while rs2241766 was generally protective of RPL. This underscores the need for controlling for modifiable covariates in genetic association studies.

Study strengths and shortcomings

The strength of our study is that it is sufficiently powered, and that RPL cases and control women were matched according to ethnicity, which reduces the problems of ethnic differences inherent in genetic association studies. Another strength is controlling for potential covariates. Our study has also some shortcomings. We could not measure serum adiponectin levels in cases and control women, which did not allow for addressing the functionality of this association, thus could not ascertain genotype–phenotype correlations. Another limitation lies in its retrospective nature, which prompts speculation on cause-effect relationship.

Conclusion

We demonstrated association of ADIPOQ rs4632532, and rs2241766 with RPL in obese women, and rs1063539 and rs16861209 in non-obese women, and both rs182052 and rs7649121 independent of BMI changes. Future studies on additional ADIPOQ variants, and populations of related and distant ethnic origin are needed to support, or rule out association of ADIPOQ variants with altered adiponectin secretion and risk of RPL.

Authors’ contributions

MD, WB: Sample processing, drafting of manuscript, RRF: Patient screening and referral, MM: Genotyping assays, WYA: Project leader, finalizing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Dr. Mona Arekat for her helpful suggestions. The expert technical assistance of Ms. Zainab H. Malalla is greatly acknowledged.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by Arabian Gulf University Research and Ethics Committee (IRB approval: 35-PI-01/15, granted on 17 October 2014), and was done according to Helsinki II Declaration. All patients provided informed written consent before blood sampling.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- ADIPOQ

adiponectin gene

- BP

blood pressure

- CI

confidence intervals

- GDM

gestational diabetes mellitus

- HWE

Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium

- LD

linkage disequilibrium

- MAF

minor allele frequency

- OR

odds ratios

- PCOS

polycystic ovarian syndrome

- PE

preeclampsia

- RPL

recurrent pregnancy loss

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphisms

Footnotes

Maryam Dendana and Wael Bahia contributed equally to the work

Contributor Information

Maryam Dendana, Phone: +216-26 784 042, Email: maryamdendana@yahoo.fr.

Wael Bahia, Email: bahiawael@gmail.com.

Ramzi R. Finan, Email: ramzifinan@hotmail.com

Mariam Al-Mutawa, Email: almutawa.mariam@gmail.com.

Wassim Y. Almawi, Email: wassim.almawi@outlook.com

References

- 1.Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine Definitions of infertility and recurrent pregnancy loss: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2013;99:63. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tang AW, Quenby S. Recent thoughts on management and prevention of recurrent early pregnancy loss. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2010;22:446–451. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e32833e124e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lashen H, Fear K, Sturdee DW. Obesity is associated with increased risk of first trimester and recurrent miscarriage: matched case-control study. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:1644–1646. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sugiura-Ogasawara M. Recurrent pregnancy loss and obesity. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;29:489–497. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hyde KJ, Schust DJ. Genetic considerations in recurrent pregnancy loss. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2015;5(3):a023119. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a023119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mathew H, Castracane VD, Mantzoros C. Adipose tissue and reproductive health. Metabolism. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2017.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ingram KH, Hunter GR, James JF, Gower BA. Central fat accretion and insulin sensitivity: differential relationships in parous and nulliparous women. Int J Obes (Lond) 2017;41:1214–1217. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2017.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bao W, Baecker A, Song Y, Kiely M, Liu S, Zhang C. Adipokine levels during the first or early second trimester of pregnancy and subsequent risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Metabolism. 2015;64:756–764. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2015.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blüher M, Mantzoros CS. From leptin to other adipokines in health and disease: facts and expectations at the beginning of the 21st century. Metabolism. 2015;64:131–145. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2014.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baviera G, Corrado F, Dugo C, Cannata ML, Russo S, Rosario D. Midtrimester amniotic fluid adiponectin in normal pregnancy. Clin Chem. 2007;53:1723–1724. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.088542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mazaki-Tovi S, Romero R, Vaisbuch E, et al. Adiponectin in amniotic fluid in normal pregnancy, spontaneous labor at term, and preterm labor: a novel association with intra-amniotic infection/inflammation. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010;23:120–130. doi: 10.3109/14767050903026481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Angelidis G, Dafopoulos K, Messini CI, et al. The emerging roles of adiponectin in female reproductive system associated disorders and pregnancy. Reprod Sci. 2013;20:872–881. doi: 10.1177/1933719112468954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palin M-C, Bourdignon VV, Murphy BD. Adiponectin and the control of female reproductive functions. Vitam Horm. 2012;90:239–287. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-398313-8.00010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cortelazzi D, Corbetta S, Ronzoni S, et al. Maternal and foetal resistin and adiponectin concentrations in normal and complicated pregnancies. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2007;66:447–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.02761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawwass JF, Summer R, Kallen CB. Direct effects of leptin and adiponectin on peripheral reproductive tissues: a critical review. Mol Hum Reprod. 2015;21:617–632. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gav025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verma PK, Prakash S, Parveen F, Faridi RM, Agrawal S. Genetic association of adipokine and UCP2 polymorphism with recurrent miscarriage among non-obese women. Reprod Bio Med Online. 2012;25:527–535. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2012.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heid IM, Wagner SA, Gohlke H, et al. Genetic architecture of the APM1 gene and its influence on adiponectin plasma levels and parameters of the metabolic syndrome in 1727 healthy Caucasians. Diabetes. 2006;55:375–384. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.02.06.db05-0747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chung HK, Chae JS, Hyun YJ, et al. Influence of adiponectin gene polymorphisms on adiponectin level and insulin resistance index in response to dietary intervention in overweight-obese patients with impaired fasting glucose or newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:552–558. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Menzaghi C, Ercolino T, Salvemini L, et al. Multigenic control of serum adiponectin levels: evidence for a role of the APM1 gene and a locus on 14q13. Physiol Genom. 2004;19:170–174. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00122.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beltcheva O, Boyadzhieva M, Angelova O, Mitev V, Kaneva R, Atanasova I. The rs266729 single-nucleotide polymorphism in the adiponectin gene shows association with gestational diabetes. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;289:743–748. doi: 10.1007/s00404-013-3029-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Machado JS, Cavalli RC, Sandrim VC, et al. Study of polymorphisms of the adiponectin gene in women with gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2012;2(3):241. doi: 10.1016/j.preghy.2012.04.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pawlik A, Teler J, Maciejewska A, Sawczuk M, Safranow K, Dziedziejko V. Adiponectin and leptin gene polymorphisms in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2017;34:511–516. doi: 10.1007/s10815-016-0866-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park JW, Park J, Jee SH. ADIPOQ gene variants associated with susceptibility to obesity and low serum adiponectin levels in healthy Koreans. Epidemiol Health. 2011;33:e201100325. doi: 10.4178/epih/e2011003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saarela T, Hiltunen M, Helisalmi S, Heinonen S, Laakso M. Adiponectin gene haplotype is associated with preeclampsia. Genet Test. 2006;10:35–39. doi: 10.1089/gte.2006.10.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peters KE, Beilby J, Cadby G, Warrington NM, Bruce DG, Davis WA, Davis TM, Wiltshire S, Knuiman M, McQuillan BM, Palmer LJ, Thompson PL, Hung J. A comprehensive investigation of variants in genes encoding adiponectin(ADIPOQ) and its receptors (ADIPOR1/R2), and their association with serum adiponectin, type 2 diabetes, insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome. BMC Med Genet. 2013;14:15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-14-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ranjzad F, Mahmoudi T, Irani Shemirani A, Mahban A, Nikzamir A, Vahedi M, Ashrafi M, Gourabi H. A common variant in the adiponectin gene and polycystic ovary syndrome risk. Mol Biol Rep. 2012;39:2313–2319. doi: 10.1007/s11033-011-0981-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Y, Liu RX, Liu H. Association of adiponectin gene polymorphisms with hypertensive disorder complicating pregnancy and disorders of lipid metabolism. Genet Mol Res. 2015;14:15213–15223. doi: 10.4238/2015.November.25.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vasseur F, Helbecque N, Lobbens S, et al. Hypoadiponectinaemia and high risk of type 2 diabetes are associated with adiponectin-encoding (ACDC) gene promoter variants in morbid obesity: evidence for a role of ACDC in diabesity. Diabetologia. 2005;48:892–899. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1729-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang D, Ma J, Brismar K, Efendic S, Gu HF. A single nucleotide polymorphism alters the sequence of SP1 binding site in the adiponectin promoter region and is associated with diabetic nephropathy among type 1 diabetic patients in the genetics of kidneys in diabetes study. J Diab Compl. 2009;23:265–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liang C, Yawei X, Qinwan W, Jingying Z, Aihong M, Yanqing C. Association of ADIPOQ single-nucleotide polymorphisms and smoking interaction with the risk of coronary heart disease in Chinese Han population. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2017;39:748–753. doi: 10.1080/10641963.2017.1324479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen SS, Gammon MD, North KE, et al. ADIPOQ, ADIPOR1, and ADIPOR2 polymorphisms in relation to serum adiponectin levels and BMI in black and white women. Obesity. 2011;19:2053–2062. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siitonen N, Pulkkinen L, Lindström J, et al. Association of ADIPOQ gene variants with body weight, type 2 diabetes and serum adiponectin concentrations: the finnish diabetes prevention study. BMC Med Genet. 2011;12:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-12-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mtiraoui N, Ezzidi I, Turki A, Chaieb A, Mahjoub T, Almawi WY. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms and haplotypes in the adiponectin gene contribute to the genetic risk for type 2 diabetes in Tunisian Arabs. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012;97:290–297. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2012.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Richardson DK, Schneider J, Fourcaudot MJ, et al. Association between variants in the genes for adiponectin and its receptors with insulin resistance syndrome (IRS)-related phenotypes in Mexican Americans. Diabetologia. 2006;49:2317–2328. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0384-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ye Y, Pu D, Liu J, Li F, Cui Y, Wu J. Adiponectin gene polymorphisms may not be associated with idiopathic premature ovarian failure. Gene. 2013;518:262–266. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang W, Wei D, Sun X, Li J, Yu X. Family-based analysis of adiponectin gene polymorphisms in Chinese Han polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2014;101:1419–1423. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boots C, Stephenson MD. Does obesity increase the risk of miscarriage in spontaneous conception: a systematic review. Semin Reprod Med. 2011;29:507–513. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1293204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khandouzi M, Deka M. The role of adiponectin in human pregnancy. Int J Res Engin Technol. 2014;2:93–100. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cikos S, Burkus J, Bukovska A, Fabian D, Rehak P, Koppel J. Expression of adiponectin receptors and effects of adiponectin isoforms in mouse pre-implantation embryos. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:2247–2255. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim ST, Marquard K, Stephens S, Louden E, Allsworth J, Moley KH. Adiponectin and adiponectin receptors in the mouse preimplantation embryo and uterus. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:82–95. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Richards JS, Liu Z, Kawai T, et al. Adiponectin and its receptors modulate granulosa cell and cumulus cell functions, fertility and early embryo development in the mouse and human. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:471–479. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.04.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hivert MF, Scholtens DM, Allard C, et al. Genetic determinants of adiponectin regulation revealed by pregnancy. Obesity. 2017;25:935–944. doi: 10.1002/oby.21805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.