Abstract

The gentamicin minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates were determined. Seventy-three percent of isolates demonstrated an MIC range of 8 to 16 μg/mL, and 27% demonstrated an MIC of 4 μg/mL or less. Significant associations between gentamicin MIC and resistance or reduced susceptibility to other antimicrobials were found.

Gonorrhea is the second most commonly reported notifiable disease in the United States, with over 395,000 reported cases in 2015.1 Left untreated, gonorrhea can cause adverse reproductive health outcomes in women, such as pelvic inflammatory disease and infertility.2 Prevention of gonorrhea sequelae depends on timely diagnosis and effective antimicrobial treatment.2 The bacterium that causes gonorrhea, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, has developed resistance to multiple classes of antimicrobials over the past 60 years3; formerly recommended therapies penicillin, tetracycline, and fluoroquinolones are no longer recommended for treatment.4 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention currently recommends dual therapy of ceftriaxone and azithromycin to treat gonorrhea. However, with cephalosporin allergy in some patients and concerning reports of cephalosporin-resistant gonorrhea,4,5 alternative noncephalosporin therapies are needed.

Gentamicin is an aminoglycoside antimicrobial that has been used in many developing countries to treat gonorrhea due to its low cost and high efficacy.6 In a recent US study, combination therapy of gentamicin and azithromycin was shown to micro-biologically cure 100% of uncomplicated urogenital gonorrhea cases.7 Although these findings indicate that gentamicin may be an efficacious treatment for uncomplicated gonorrhea, little is known about gentamicin susceptibility among strains in the United States.

METHODS

We used data collected through the Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project (GISP) to investigate N. gonorrhoeae gentamicin minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) distribution. Established in 1986, GISP allows the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to conduct sentinel surveillance of N. gonorrhoeae antimicrobial susceptibility to inform treatment recommendations. Monthly, 25 to 30 participating STD clinics collect urethral N. gonorrhoeae isolates from the first 25 men presenting with gonococcal urethritis. Associated clinical and demographic data, including age, gender, gender of sex partners, and treatment are abstracted from the medical records by the clinic staff. Isolates undergo susceptibility testing by agar dilution for azithromycin, cefixime, ceftriaxone, ciprofloxacin, penicillin, tetracycline, and gentamicin at regional laboratories. Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project began gentamicin susceptibility testing in 2015. Susceptibility results are generated as MICs. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute interpretive criteria for gentamicin have not been established. However, criteria based on previous MIC comparisons and clinical cure data have characterized MICs of 4 μg/mL or less as susceptible, 8 to 16 μg/mL as intermediate susceptible, and 32 μg/mL or higher as resistant.8–10 Bivariate analyses of gonococcal infection and isolate characteristics were conducted using χ2 statistics.

RESULTS

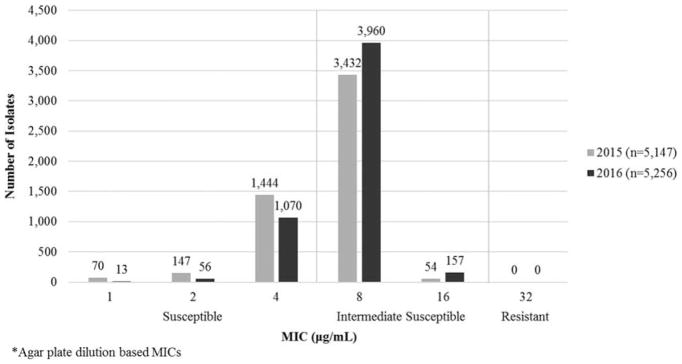

During 2015 and 2016, 10,403 urethral N. gonorrhoeae isolates were tested for gentamicin susceptibility. Gentamicin MICs ranged from 1 to 16 μg/mL. Of 10,403 isolates, 7603 (73%) demonstrated intermediate susceptibility (MIC range, 8–16 μg/mL), 2800 (27%) demonstrated full susceptibility (MIC, ≤4 μg/mL), and none demonstrated resistance (MIC, ≥32 μg/mL) (Fig. 1). The MIC50 and MIC90 were 8 μg/mL. The percentage of intermediate susceptible isolates increased from 68% in 2015 to 78% in 2016 (P < 0.0001).

Figure 1.

Susceptibility of N. gonorrhoeae isolates to gentamicin*—Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project, United States, 2015–2016.

Isolates obtained from clinics in the west census region demonstrated the highest prevalence of intermediate susceptibility (84%), followed by the south (74%), the northeast (68%), and the midwest (61%) (P < 0.0001) (Table 1). Isolates from patients identifying as gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (gender of sex partner data are collected in accordance with local clinic practice and can include chart notation from previous visits, patient self-report of sexual orientation, or both, or sex of sex partner [from past 3, 6, or 12 months]) demonstrated a higher prevalence of intermediate susceptibility (81%) than isolates from men who have sex only with women (68%) (P < 0.0001). Eighty percent of the isolates from patients known to be living with diagnosed HIV demonstrated intermediate susceptibility to gentamicin compared with 72% of isolates from patients not known to be living with diagnosed HIV (P < 0.0001).

TABLE 1.

Differences in N. gonorrhoeae Gentamicin Susceptibility Patterns by US Census Region, Sex of Sex Partner, and HIV Status—Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project, United States, 2015–2016*

| Susceptible, N (%) | Intermediate Susceptible, N (%) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 2800 (26.9%) | 7603 (73.1%) | 10,403 |

| Region† | |||

| West | 651 (16.4%) | 3311 (83.6%) | 3962 |

| Midwest | 1145 (40.0%) | 1751 (60.5%) | 2896 |

| South | 592 (26.0%) | 1686 (74.0%) | 2278 |

| Northeast | 412 (32.5%) | 855 (67.5%) | 1267 |

| Gender of sex partner† | |||

| MSW | 2023 (31.6%) | 4376 (68.4%) | 6399 |

| MSM‡ | 752 (19.2%) | 3166 (80.8%) | 3918 |

| Unknown | 25 (29.1%) | 61 (70.9%) | 86 |

| HIV status† | |||

| Not known to be living with diagnosed HIV | 2435 (28.1%) | 6236 (71.9%) | 8671 |

| Known to be living with diagnosed HIV | 195 (19.6%) | 801 (80.4%) | 996 |

| Unknown | 170 (23.1%) | 566 (76.9%) | 736 |

Clinical sites include: Albuquerque, NM; Atlanta, GA; Birmingham, AL; Boston, MA; Buffalo, NY; Chicago, IL; Cleveland, OH; Columbus, OH; Dallas, TX; Greensboro, NC; Honolulu, HI; Indianapolis, IN; Kansas City, MO; Los Angeles, CA; Las Vegas, NV; Minneapolis, MN; New Orleans, LA; New York, NY; Orange County, CA; Philadelphia, PA; Phoenix, AZ; Pontiac, MI; Portland, OR; San Diego, CA; Seattle, WA; San Francisco, CA; Tripler Army Medical Center, HI.

P < 0.0001.

Includes men who have sex with men and women.

MSM indicates men who have sex with men; MSW, men who have sex with women only.

Twenty-eight isolates demonstrated elevated MIC (MIC ≥0.125 μg/mL) to ceftriaxone; 25 (89%) of these isolates also demonstrated intermediate susceptibility to gentamicin (Table 2). Of the 323 isolates demonstrating elevated MIC (MIC ≥2.0 μg/mL) to azithromycin, 305 (94%) demonstrated intermediate susceptibility to gentamicin (P < 0.0001). Intermediate gentamicin susceptibility was associated with resistance to penicillin, tetracycline, ciprofloxacin, and cefixime, and azithromycin elevated MIC (P < 0.05). Eighty-six (<1%) sampled gonococcal urethritis infections were treated primarily with gentamicin; 72 (84%) corresponding isolates demonstrated intermediate susceptibility to gentamicin. Of the 86 sampled infections treated with gentamicin, 82 (95%) were treated in combination with azithromycin, 3 (3%) were treated in combination with doxycycline, and 1 (1%) was treated only with gentamicin.

TABLE 2.

Associations Between Susceptibility of N. gonorrhoeae Isolates to Gentamicin and Resistance to Penicillin, Tetracycline, or Ciprofloxacin, or Elevated MICs to Ceftriaxone, Cefixime, or Azithromycin*—GISP, United States, 2015–2016

| Susceptible to Gentamicin | Intermediate Susceptible to Gentamicin | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 2800 (26.9%) | 7603 (73.1%) | |

| Penicillin† | Susceptible | 2433 (28.1%) | 6227 (71.9%) |

| Resistant | 367 (21.1%) | 1376 (78.9%) | |

| Tetracycline† | Susceptible | 2313 (29.0%) | 5655 (71.0%) |

| Resistant | 487 (20.0%) | 1948 (80.0%) | |

| Ciprofloxacin† | Susceptible | 2259 (28.8%) | 5586 (71.2%) |

| Resistant | 541 (21.1%) | 2017 (78.9%) | |

| Ceftriaxone | Susceptible | 2797 (27.0%) | 7578 (73.0%) |

| Elevated MIC | 3 (10.7%) | 25 (89.3%) | |

| Cefixime‡ | Susceptible | 2796 (27.0%) | 7565 (73.0%) |

| Elevated MIC | 4 (9.5%) | 38 (90.5%) | |

| Azithromycin† | Susceptible | 2782 (27.6%) | 7298 (72.4%) |

| Elevated MIC | 18 (5.6%) | 305 (94.4%) |

Penicillin resistance = MIC ≥2.0 μg/mL, tetracycline resistance = MIC ≥2.0 μg/mL, ciprofloxacin resistance = MIC ≥1.0 μg/mL, ceftriaxone elevated MIC = MIC ≥0.125 μg/mL, cefixime elevated MIC = MIC ≥0.25 μg/mL, azithromycin elevated MIC = MIC ≥2.0 μg/mL.

P < 0.0001.

P = 0.0109.

DISCUSSION

This report provides findings from the largest surveillance sample of N. gonorrhoeae isolates tested for gentamicin susceptibility to date. Without the existence of gentamicin Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute clinical breakpoint criteria, the clinical interpretation of our findings is limited. These findings may serve as a measure of the MIC distribution when such interpretative criteria become established for gentamicin.

Previous international studies have assessed gonococcal gentamicin susceptibility by agar dilution. A 2009 survey of gentamicin susceptibility on 1366 gonococcal isolates from 17 European Union countries found that 16% of isolates demonstrated an MIC of 4 mg/L (equivalent to μg/mL), and 79% of isolates demonstrated an MIC of 8 mg/L.9 A 2007 survey of 100 isolates from Malawi showed a stable agar dilution MIC range of 1 to 4 μg/mL in the context of 14 years of routine use of dual treatment with gentamicin and doxycycline for urethritis.8,10 Our findings indicate the continued susceptibility of N. gonorrhoeae to gentamicin, but diverge from previous reports in demonstrating a wider and higher MIC range, with 71% of the isolates demonstrating an MIC of 8 μg/mL and 2% of the isolates demonstrating an MIC of 16 μg/mL. The increase in the proportion of intermediate susceptible isolates between 2015 and 2016 points to the possibility that susceptibility to gentamicin might be decreasing; continued surveillance of gentamicin susceptibility is needed.

This report is subject to limitations. Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project only collects male urethral N. gonorrhoeae isolates. Although some studies suggest that gonococcal antimicrobial susceptibility surveillance based on urethral isolates adequately reflects, at the population level, the susceptibilities of circulating N. gonorrhoeae strains, other studies suggest that disparities in susceptibility exist by anatomic site of infection and sex.11,12 It may thus be prudent for future gentamicin susceptibility studies to include rectal, pharyngeal, and cervical isolates. Moreover, GISP participants do not comprise a nationally representative sample of all persons with gonorrhea; only men presenting at participating STD clinics with diagnosed urethral gonorrhea are included. Despite lacking national representation, GISP does enable monitoring of antimicrobial susceptibility trends across US geographic areas.2

Because gonorrhea is not routinely treated with gentamicin in the United States, this study could not assess the correlation between gentamicin treatment patterns and MIC. Furthermore, GISP does not collect clinical outcome information; this report thus could not assess the relationship between gentamicin MIC and treatment outcome. Further studies are needed to assess the relationship between treatment practices and outcome and gentamicin MIC.

The high incidence of gonorrhea coupled with increasing antimicrobial resistance warrants the consideration of alternative therapies. In combination with other therapies, gentamicin can be a low-cost and efficacious alternative therapy; continued surveillance of gentamicin susceptibility and further investigation of gentamicin as therapy for gonorrhea is warranted.

Acknowledgments

Data in this manuscript were collected through CDC’s Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project (GISP). The authors thank the participating clinical sites that collected specimens and the laboratories that conducted antimicrobial susceptibility testing for GISP: King K. Holmes and Olusegun O. Soge (University of Washington); Carlos del Rio, Baderinwa Offutt, and Tamayo Barnes (Emory University); Jonathan Zenilman, Kar Mun Neoh, Stefan Riedel (Johns Hopkins University); Grace Kubin, Tamara Baldwin, and Carol Rodriguez (Texas); Edward W. Hook, III and Paula Dixon (University of Alabama at Birmingham); and Kevin Pettus and Samera Sharpe (CDC).

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Conflicts of interest and source of funding: none declared.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2015. Atlanta, GA: Department of Health and Human Services; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirkcaldy RD, Harvey A, Papp JR, et al. Neisseria gonorrhoeae antimicrobial susceptibility surveillance—The Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project, 27 sites, United States, 2014. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2016;65:1–19. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6507a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Workowski KA, Berman SM, Douglas JM. Emerging antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae: Urgent need to strengthen prevention strategies. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:606–613. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-8-200804150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barry PM, Klausner JD. The use of cephalosporins for gonorrhea: The impending problem of resistance. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2009;10:555–577. doi: 10.1517/14656560902731993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelkar PS, Li JT. Cephalosporin allergy. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:804–809. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra993637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ross JD, Lewis DA. Cephalosporin resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae: Time to consider gentamicin? Sex Transm Infect. 2012;88:6–8. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2011-050362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kirkcaldy RD, Weinstock HS, Moore PC, et al. The efficacy and safety of gentamicin plus azithromycin and gemifloxacin plus azithromycin as treatment of uncomplicated gonorrhea. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:1083–1091. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown LB, Krysiak R, Kamanga G, et al. Neisseria gonorrhoeae antimicrobial susceptibility in Lilongwe, Malawi, 2007. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37:169–172. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181bf575c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chisholm SA, Quaye N, Cole MJ, et al. An evaluation of gentamicin susceptibility of Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates in Europe. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:592–595. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lule G, Behets FM, Hoffman IF, et al. STD/HIV control in Malawi and the search for affordable and effective urethritis therapy: A first field evaluation. Genitourin Med. 1994;70:384–388. doi: 10.1136/sti.70.6.384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kidd S, Zaidi A, Asbel L, et al. Comparison of antimicrobial susceptibilities of pharyngeal, rectal, and urethral Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates among men who have sex with men. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:2588–2595. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04476-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hottes TS, Lester RT, Hoang LM, et al. Cephalosporin and azithromycin susceptibility in Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates by site of infection, British Columbia, 2006 to 2011. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40:46–51. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31827bd64c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]