Abstract

The current study examined whether monetary incentives could increase engagement and achievement in a job-skills training program for unemployed, homeless, alcohol-dependent adults. Participants (n = 124) were randomized to a No Reinforcement group (n = 39), during which access to the training program was provided but no incentives were given; a Training Reinforcement group (n = 42), during which incentives were contingent on attendance and performance; or an Abstinence & Training Reinforcement group (n = 43), during which incentives were contingent on attendance and performance, but access was only granted if participants were abstinent from alcohol. Abstinence & Training Reinforcement and Training Reinforcement participants advanced further in training and attended more hours than No Reinforcement participants. Monetary incentives appear effective in promoting engagement and achievement in a job-skills training program among individuals who often do not take advantage of training programs.

Keywords: therapeutic workplace, homeless, alcohol abuse, job-skills training, poverty, monetary incentives

In a recent analysis of major social and behavioral risk factors, poverty (< 200% poverty line) was associated with the greatest number of Quality-Adjusted Life Years lost in the United States (Muennig, Fiscella, Tancredi, & Franks, 2010). This measure combines the absolute duration of life with disease burden that impacts the quality of those years, and was calculated from ages 18–85 after adjusting for education. In that study, poverty was a greater risk factor than smoking status. In the same analysis, education (< high school) was associated with the third greatest loss of Quality-Adjusted Life Years, more than obesity. This dramatic finding places poverty and lack of education as two of the most important and costly public health problems today, and is consistent with other analyses demonstrating that low socioeconomic status is associated with greater incidence of a range of health-related problems and consequences such as cardiovascular disease (Kaplan & Keil, 1993), depression (Everson, Maty, Lynch, & Kaplan, 2002), diabetes (Everson et al., 2002), arthritis (Cunningham & Kelsey, 1984), tuberculosis (Cantwell, McKenna, McCray, & Onorato, 1998), obesity (Everson et al., 2002), and mortality (Feinstein, 1993).

Poverty and lack of education are intertwined problems. The most proximal cause of poverty is unemployment or underemployment, a problem that is difficult to address if individuals lack sufficient education and job skills. Brief “quick entry” employment interventions that assist individuals with only their most pressing employment-related needs (e.g., résumé preparation) are common, but frequently have little or no beneficial effect (Magura, Staines, Blankertz, & Madison, 2004). More intensive interventions to address poverty that include an educational or training component are effective for those who participate regularly, but most low-income individuals do not participate regularly in such interventions and therefore receive no measurable benefit (Bos et al., 2002; Hamilton, 2002).

Monetary incentives have been shown to function as effective reinforcers to promote a wide variety of positive health-related behaviors when they are delivered contingent on verification of that behavior. For example, incentives have been shown to promote abstinence from alcohol and other drugs (Higgins, Silverman, & Heil, 2008; Silverman, Kaminski, Higgins, & Brady, 2011), medication adherence (Rounsaville, Rosen, & Carroll, 2008), weight loss (Volpp et al., 2008), and use of preventive dental care (Riccio et al., 2010). Preliminary evidence suggests incentives may also be effective in promoting attendance in a job-skills training program (Silverman, Chutuape, Bigelow, & Stitzer, 1996). Delivering a portion of all of an employee’s pay based on work output is also known to increase productivity, provided that the performance pay is delivered contingent on the desired behavior (Bucklin & Dickinson, 2001; Koffarnus, DeFulio, Sigurdsson, & Silverman, in press).

The delivery of monetary incentives contingent on desirable health behavior is rooted in firm basic science foundation on the effects of reinforcement (Catania, 2007). The benefits of attending a job-skills training program (e.g., increased chance of employment, reduction in poverty), as with the consequences of many positive health behaviors, are often quite delayed. Delayed outcomes exert relatively little control over behavior (Bickel & Marsch, 2001). Immediately available reinforcers, such as monetary incentives, can much more readily promote positive behavior than delayed health gains. This is especially true for people of low socioeconomic status and/or alcohol-dependent adults, as these populations undervalue delayed outcomes to a greater extent (Bobova, Finn, Rickert, & Lucas, 2009; Green, Myerson, Lichtman, Rosen, & Fry, 1996; Mitchell, Fields, D'Esposito, & Boettiger, 2005; Petry, 2001). Given the large impact of poverty on Quality-Adjusted Life Years and the staggering medical costs of the problematic health outcomes associated with poverty, monetary incentives to promote attendance and performance in programs that reduce the incidence of unemployment or underemployment could be justified.

The current study extends previous work on monetary incentives for pro-health behaviors and performance pay for workplace productivity by examining the use of monetary incentives to promote engagement and performance in a job-skills training program for homeless, unemployed, alcohol-dependent adults. The current study used the therapeutic workplace model that provides access to job-skills training contingent on desirable behaviors such as drug abstinence (Silverman, 2004; Silverman, DeFulio, and Sigurdsson, 2012). Based on the interests and skills of participants in the early therapeutic workplace research (Silverman, Chutuape, Svikis, Bigelow, & Stitzer, 1995), the therapeutic workplace was designed to teach participants skills that would be useful in office jobs, including typing and computer use. Importantly, our early research showed that participants found the therapeutic workplace typing and keypad training to be “interesting,” “enjoyable,” “challenging,” and “helpful” (Silverman et al., 1996).

This report describes a secondary analysis of data collected during a randomized controlled clinical trial that evaluated the effectiveness of the therapeutic workplace in promoting abstinence from alcohol in homeless alcohol dependent adults (Koffarnus et al., 2011). All participants were invited to attend and receive training to learn basic computer skills, and in this study we examined the effects of the different payment contingencies on engagement and acquisition of job skills in the job skills training program. The unique design of this study allowed us to experimentally control payment contingencies and manipulate whether participants received payment or experienced the more typical situation of unpaid job-skills training, isolating the payment contingencies for analysis. We expected that the groups receiving incentives for attending and performing well on the training programs would attend more hours and would progress further on the training programs than the group that did not receive the monetary incentives.

Method

The primary outcome variable of this randomized clinical trial to promote alcohol abstinence was alcohol use. That outcome and detailed methodology meeting the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) criteria for complete clinical trial description have been reported elsewhere, and portions of it have been reproduced here for reference (Koffarnus et al., 2011).

Setting and Participant Selection

This study was conducted at the Center for Learning and Health, a treatment-research unit at the Johns Hopkins Bayview campus (Baltimore, MD, USA) and was approved by the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board. Participants were enrolled from December 2001 to October 2005. Study inclusion criteria required that participants were homeless, were unemployed, were at least 18 years of age, and met DSM-IV criteria for alcohol dependence. Participant characteristics by study group are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics by study group.

| Abstinence & Training Reinforcement (n = 43) |

Training Reinforcement (n = 42) |

No Reinforcement (n = 39) |

p value (Fisher’s Exact Test) |

p value (F test) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 42.0 (8.5) | 45.2 (8.0) | 43.0 (7.6) | 0.19 | |

|

| |||||

| Gender, % Male | 79.1 | 81.0 | 82.1 | 0.96 | |

|

| |||||

| Race, % | 0.06 | ||||

|

| |||||

| White | 62.8 | 42.9 | 43.6 | ||

|

| |||||

| Black | 37.2 | 50.0 | 56.4 | ||

|

| |||||

| Other | 0 | 7.1 | 0 | ||

|

| |||||

| Married, % | 0 | 0 | 2.6 | 0.31 | |

|

| |||||

| High School Diploma or GED, % | 65.1 | 59.5 | 61.5 | 0.87 | |

|

| |||||

| Usually unemployed past 3 years prior to intake, % | 93.0 | 97.6 | 92.3 | 0.85 | |

|

| |||||

| DSM IV Diagnosis, % | |||||

|

| |||||

| Alcohol dependence | 100 | 100 | 100 | - | |

|

| |||||

| Cocaine dependence | 34.9 | 33.3 | 35.9 | 0.97 | |

|

| |||||

| Opioid dependence | 20.9 | 11.9 | 28.2 | 0.19 | |

|

| |||||

| WRAT3 | |||||

|

| |||||

| Grade level reading, mean (SD) | 8.7 (4.0) | 8.7 (3.9) | 8.4 (4.2) | 0.92 | |

|

| |||||

| Grade levels spelling, mean (SD) | 6.8 (3.8) | 6.8 (3.7) | 7.3 (4.0) | 0.80 | |

Note. Adapted from Koffarnus et al., 2011.

Experimental Design and Description of Study Groups

Eligible participants were randomly assigned to one of three experimental groups after stratifying on a number of key alcohol- and drug-use variables: the No Reinforcement (n=39), Training Reinforcement (n=42), or Abstinence & Training Reinforcement (n=43) group. Note that in our previous report on this study (Koffarnus et al., 2011), groups were referred to as “Unpaid” instead of “No Reinforcement,” “Paid” instead of “Training Reinforcement,” and “Contingent Paid” instead of “Abstinence & Training Reinforcement.” Participants assigned to the No Reinforcement group were invited to receive training independent of their breath sample results, and they did not earn monetary vouchers for their participation in the workplace. This condition is similar to typical training programs for low-income and unemployed adults (Bos et al., 2002; Hamilton, 2002). Participants in the Training Reinforcement group could earn an hourly wage in vouchers for attending the workplace and additional productivity pay for performance on the training programs. These participants were allowed to work and earn vouchers independent of whether their breath samples were positive for alcohol. Participants in the Abstinence & Training Reinforcement group received training and payment similar to participants in the Training Reinforcement Training group, but access to the workplace and the opportunity to earn voucher pay was contingent upon the alcohol content of their breath samples. An Abstinence & Training Reinforcement participant who provided an alcohol-positive (BAL ≥ 0.004 g/dl) breath sample was not permitted access to the workplace on that day and received a temporary decrease in pay on subsequent days (see below).

Therapeutic Workplace and Training Programs

All participants were invited to receive training in a specialized program called the Therapeutic Workplace for 4 hours every weekday throughout a 26-week intervention period, and were required to provide breath samples under observation that were tested for alcohol (see Koffarnus et al., 2011 for a description of breath sample collection and obtained results). The therapeutic workplace training program is delivered via a web-based application, which allows staff to administer and electronically monitor treatment and training for each trainee. Aspects of the treatment most relevant to the keyboarding training are described below in detail. Other details of the web-based therapeutic workplace treatment are described in detail elsewhere (Silverman et al., 2005; Silverman et al., 2007).

In the workplace, participants were taught keyboarding skills using two computer-based training programs (see Dillon, Wong, Sylvest, Crone-Todd, & Silverman, 2004 for a detailed description of the training programs). One training program, “Typing”, taught participants to become proficient at using a standard QWERTY keyboard. Trainees were presented with a series of characters, and were required to key an identical string of characters. Characters that matched the criterion characters were considered correct, with mismatched characters or omissions considered incorrect. After 1 min of keying (a “timing”), the number of incorrect and correct characters were displayed on the participant’s screen along with any earnings for those characters. Participants could then initiate another 1-min timing. The program was arranged in a series of steps, with each step focusing on a small number of new characters that hadn’t previously been trained. These steps were intermixed with additional steps that focused on proficiency, and required trainees to key previously-learned characters at increased rates. A second program, “Keypad”, was similar to the Typing program but was designed to train rapid entering of characters on a numeric keypad. Trainees worked on the training programs for 2 hours in the morning (10:00 a.m. to 12:00 p.m.) and for 2 hours in the afternoon (1:00 p.m. to 3:00 p.m.).

Monetary Incentives

Participants in the Abstinence & Training Reinforcement and Training Reinforcement groups could earn an hourly wage as well as pay for performance on the training programs. All earnings were paid in monetary vouchers that were automatically added to each participant’s voucher account and displayed on the participant’s computer screen. Voucher earnings were exchangeable for goods and services in the community that were purchased for participants by staff (e.g., gift cards, rent, utility payments).

Base pay

Hourly base pay began at an initial low rate of $1.00/hour and increased by $.10 to a maximum of $5.00/hour for each day a participant arrived on time (i.e., 10 a.m.) and completed a work shift (≥3.5 out of 4 hours in attendance). The base pay rate was reset to $1.00/hour if the participant failed to complete a work shift, or arrived late to the workplace (Training Reinforcement and Abstinence & Training Reinforcement groups). Base pay was also reset for Abstinence & Training Reinforcement participants if a breath sample was positive or missed. Once the base pay hourly rate was reset, it increased again by $.10 per hour for each day the participant met the attendance and abstinence requirements. After 9 consecutive days of meeting each of the requirements, base pay was restored to the value in place before the reset. Productivity pay was not affected by a reset. To allow for some flexibility, participants started training with credits of 5 “late-not-reset days” and 5 “personal days.” In addition, participants earned 1 “late-not-reset day” for every 10 completed work shifts and 1 “personal day” for every 5 completed work shifts. Participants could use “late-not-reset” or “personal” days to prevent a reset for being late or failing to work a complete work shift, respectively.

Productivity pay

Training Reinforcement and Abstinence & Training Reinforcement participants were able to earn additional voucher pay for performance on the training programs. First, participants could earn and lose voucher money for correct and incorrect characters, respectively. Second, participants could earn bonuses for each step they passed. On most steps, participants earned 3 cents for every 10 correct characters and lost 1 cent for every incorrect character. The bonuses began at $1.00 and increased in value as trainees progressed through the program.

Outcome Measures

Participants were all invited to attend the therapeutic workplace for a 26-week period, but due to the differential occurrence of holidays and other closings during individual participants’ enrollment in the trial, this 26-week period contained different numbers of work days for individual participants. The number of days the therapeutic workplace was open for any participant ranged from 108 to 131 days. Since many of the outcome variables would be biased by total available training time, all analyses for all participants were restricted to the first 108 days of possible attendance.

As a measure of obtained skills, steps achieved on the Typing and Keypad programs were a primary outcome measure, as was the total steps achieved across both keying programs. Total cumulative hours attended was a measure of engagement, and steps completed per hour was a measure of rate of skill attainment. Amount of time “on-task” was measured by calculating the number of 1-min timings per hour that were initiated while in the workplace. Keying speed was measured in two ways: characters typed per timing initiated as a measure of speed while on-task, and characters typed per minute in the workplace as a measure of overall productivity in the workplace. Keying accuracy was also examined by calculating the percentage correct [correct characters keyed / (correct + incorrect characters keyed)] on the Typing and Keypad programs individually, as well as an overall combined accuracy.

Data Analysis

Categorical participant characteristics were compared with Fisher’s exact tests, while continuous variables were compared with one-way ANOVAs. Levene’s median test was used to determine whether group variances were sufficiently similar to conduct one-way ANOVAs for each outcome measure. For the outcomes that passed Levene’s median test, one-way ANOVAs were conducted to look for a group effect, and significant results were followed with Tukey’s post hoc tests on all group pairings. For the measures that did not pass Levene’s median test and the ordinal steps achieved measures, nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis ANOVAs were conducted, and significant results were followed with Dunn’s post hoc tests on all group pairings. Levene’s median tests, Fisher’s exact tests, and one-way ANOVAs were carried out in SPSS 17.02 (IBM Corporation, Somers, NY, USA), and Kruskal-Wallis ANOVAs were conducted in Prism 5.03 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). For all inferential statistical tests, α was set to 0.05. For each outcome measure we also calculated the probabilistic index [P̂ (X > Y)], or the probability that a randomly selected individual from an experimental (Abstinence & Training Reinforcement or Training Reinforcement) group showed greater performance than a random individual from the control (No Reinforcement) group as a measure of effect size (Acion, Peterson, Temple, & Arndt, 2006). This measure ranges from 0 (experimental group universally lower performance than control) to 1 (experimental group universally greater performance), with 0.5 indicating no difference between the groups.

Results

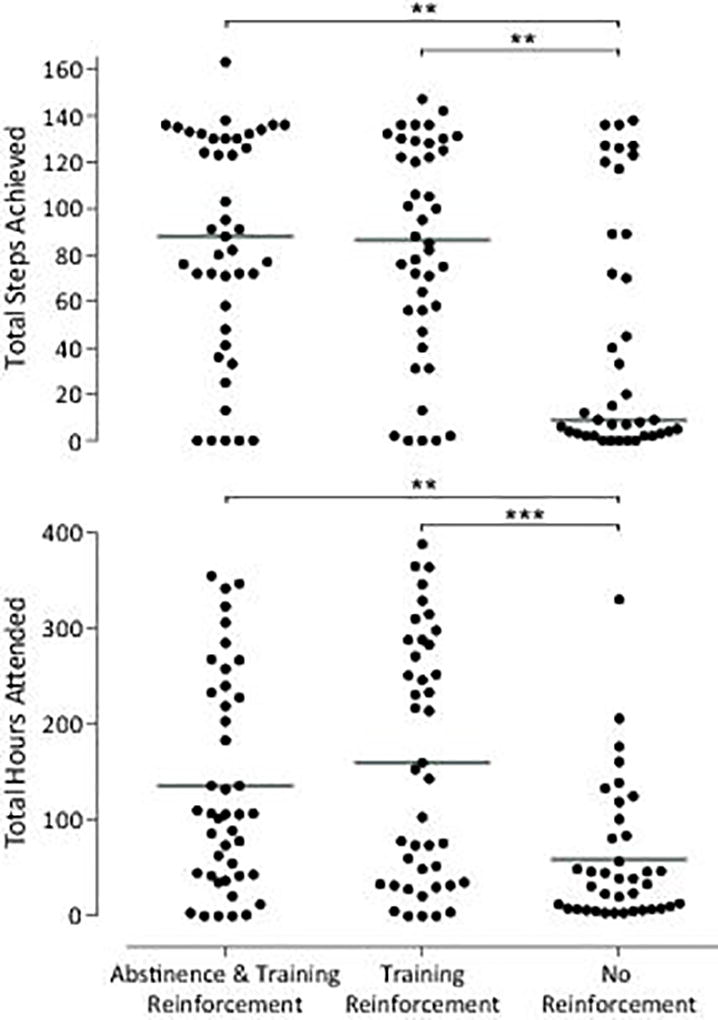

Overall productivity, as measured by steps completed on the training programs, was significantly higher in the Abstinence & Training Reinforcement and Training Reinforcement groups than in the No Reinforcement group (Table 2). This was true for the Typing and Keypad programs individually, as well as for the overall total steps completed (Figure 1, top panel). The Abstinence & Training Reinforcement and Training Reinforcement groups did not differ from one another on any of these measures. The Abstinence & Training Reinforcement and Training Reinforcement groups also attended the workplace for a significantly longer total duration than the No Reinforcement group (Table 2, Figure 1, bottom panel). While the Abstinence & Training Reinforcement group attended somewhat less than the Training Reinforcement group, this difference was not significant. The rate of step completion while in the workplace did not differ as a function of group.

Table 2.

Group means or medians for each outcome measure and the results of ANOVAs and post hoc tests comparing study groups.

| Group means or medians a | ANOVA results a | P̂ (X > No Voucher) b | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||

| Abstinence & Training Reinforcement |

Training Reinforcement |

No Reinforcement |

F or H |

df |

p value |

Abstinence & Training Reinforcement |

Training Reinforcement |

||

| Overall steps achieved c | 91 ** | 88 ** | 10.5 | 13.4 | 2 | .001 | .71 | .70 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Typing steps achieved c | 49 ** | 48 * | 9 | 12.2 | 2 | .002 | .70 | .69 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Keypad steps achieved c | 42 *** | 42 *** | 3 | 17.9 | 2 | < .001 | .74 | .73 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Total hours attended d | 106 ** | 148 ** | 36 | 14.6 | 2 | < .001 | .71 | .73 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Steps completed per hour in workplace d | 0.64 | 0.52 | 0.61 | 0.4 | 2 | n.s. | .52 | .51 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Timings initiated per hour in workplace d | 36 *** | 33 | 29 | 13.1 | 2 | .001 | .74 | .64 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Characters typed per timing initiated | 63 | 63 | 63 | 0.0 | 2,115 | n.s. | .53 | .52 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Characters typed per min. in workplace | 38 ** | 34 | 27 | 6.8 | 2,115 | .002 | .73 | .64 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Overall accuracy (% correct) d | 97.8 * | 97.3 | 96.0 | 9.2 | 2 | .01 | .67 | .67 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Typing accuracy (% correct) d | 97.1 * | 97.2 | 95.4 | 7.7 | 2 | .02 | .65 | .66 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Keypad accuracy (% correct) d | 98.2 | 97.9 | 97.2 | 3.7 | 2 | n.s. | .61 | .61 | |

Note. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences from the No Reinforcement group with post hoc tests (* p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001).

The Abstinence & Training Reinforcement and Training Reinforcement groups were not different from one another on any of these outcome measures. n.s. = not statistically significant.

Means and one-way ANOVAs (F values) are reported for ratio scale outcome measures that passed Levene’s Median Test, while medians and Kruskal-Wallis ANOVAs (H values) are reported for ordinal measures or those that did not pass Levene’s Median Test.

The probability that a random member of the Abstinence & Training Reinforcement or Training Reinforcement group performed better than a random member of the No Reinforcement group.

Ordinal outcome measure.

Did not pass Levene’s Median Test.

Figure 1.

Total steps achieved (top panel) and total hours attended (bottom panel) for each of the three groups. Individual points represent individual participants, and horizontal bars indicate the median values for the group. Asterisks indicate significant differences between groups with Dunn’s post hoc tests (** p < .01, *** p < .001).

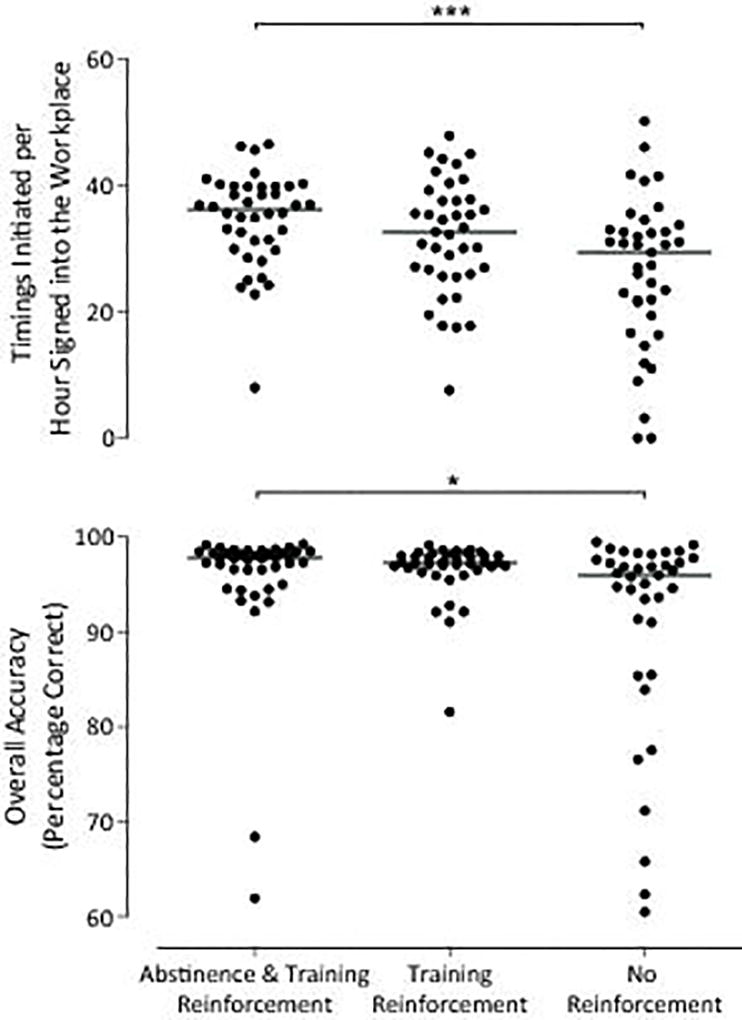

Certain aspects of training performance were greatest in the Abstinence & Training Reinforcement group (Table 2). The number of 1-min timings initiated per hour in the workplace was significantly greater in the Abstinence & Training Reinforcement group compared to the No Reinforcement group, with the Training Reinforcement group initiating an intermediate number of timings (Figure 2, top panel). Typing speed while on task was not affected by group assignment, as shown by the similar number of characters typed per 1-min timing initiated in the three groups. Likely as a result of the greater number of initiated timings, overall characters per minute in the workplace was significantly greater in the Abstinence & Training Reinforcement group compared to the No Reinforcement group, with the Training Reinforcement group keying at an intermediate rate. Accuracy was also affected by the payment contingencies. The Abstinence & Training Reinforcement group tended to have somewhat higher rates of accuracy than the No Reinforcement group, and this trend was significant for overall accuracy (Figure 2, bottom panel) and Typing accuracy. The Training Reinforcement group had intermediate accuracy rates that were not statistically different from either of the other groups.

Figure 2.

Timings initiated per hour signed into the workplace (top panel) and overall accuracy (bottom panel) for each of the three groups. Individual points represent individual participants, and horizontal bars indicate the mean values for the group. Asterisks indicate significant differences between groups with Dunn’s post hoc tests (* p < .05, *** p < .001).

Discussion

Overall, the results confirm the benefit of payment contingencies in increasing achievement in a job-skills training program, engagement in a job-skills training program, and performance quality while on task in a job-skills training program. This is most clearly evidenced by the overall achievement of the two groups receiving paid training in the current study, as the Abstinence & Training Reinforcement and Training Reinforcement groups completed a median 91 and 88 steps, respectively, while the No Reinforcement group completed just 10.5 (Table 2, Figure 1, top panel). In addition, rate of timing initiation, keying speed, and accuracy were higher in the Abstinence & Training Reinforcement group relative to the No Reinforcement group. The Training Reinforcement group had intermediate values for each of these measures, which may have been due to the greater alcohol use in this group compared to the Abstinence & Training Reinforcement group (Koffarnus et al., 2011). These results confirm and expand upon a growing literature demonstrating the effectiveness of monetary incentives to reinforce a wide range of desirable behavior (see Higgins et al., 2008 for a review). Much of the work in this area has focused on reinforcing abstinence in substance users. Although abstinence from alcohol was a focus of the current trial (see Koffarnus et al., 2011), the current study demonstrates that monetary incentives are effective at increasing other desirable behaviors such as job-skills training performance either in conjunction with (Abstinence & Training Reinforcement group) or independent of (Training Reinforcement group) abstinence contingencies.

Governments have increasingly supported the use of monetary incentives as a way to promote healthy behavior patterns among citizens (Riccio et al., 2010). Given the seriousness of poverty as a public health problem, arranging an incentive program to promote attendance and performance in job-skills training programs may be an effective way of addressing poverty. Incentives delivered contingent on attendance and performance in job-skills or educational programs would not only work to alleviate poverty by delivering monetary vouchers to people who could benefit from them, but would have the additional benefit of promoting attendance, performance, and skill acquisition in the training program. Therefore, such an intervention has the potential to address both short-term poverty through incentives delivered in the context of the intervention, and long-term poverty by addressing one of the major underlying causes of poverty, lack of sufficient education, or job skills to gain and maintain employment.

The current study is limited by the relatively narrow focus of the job skills training (i.e., to typing and keypad training) and by the fact that we did not show whether the training produced changes in the employability or employment of participants. It will be important to determine if incentives can be used to promote engagement and progress in a more comprehensive education and training program and if that training improves the employment of participants. It also remains to be seen whether incentives and training can produce meaningful changes in the lives of low-income unemployed adults by promoting employment and reducing poverty.

Monetary incentives may not be necessary for all individuals in poverty who could benefit from job-skills training. In the current experiment, a subset of individuals in the No Reinforcement group attended the workplace regularly and made substantial progress on the training programs even though they received no monetary incentives for doing so (see Figure 1, top panel). These individuals may be sufficiently motivated by other factors alone (e.g., skill acquisition). However, participants in the No Reinforcement group who chose to attend regularly were few in number, and this experiment makes clear the need for an additional motivational factor to promote engagement and performance in the majority of this sample of homeless, unemployed, alcohol-dependent adults. For individuals in poverty, monetary incentives effectively serve this purpose.

Intensive “capital investment” programs to promote employment in low-income populations have attempted to provide basic and job skills training to establish skills that individuals will need to succeed in the workplace (Bos et al., 2002; Hamilton, 2002). These programs have been relatively ineffective, in part because eligible individuals fail to attend the programs sufficiently and to acquire needed skills (Bos et al., 2002; Hamilton, 2002). This study shows that monetary incentives for both attendance and for performance on training programs can be highly effective in engaging low-income, unemployed individuals in training and increasing their skill acquisition. The use of incentives in adult education programs could be a critical component in an intervention to reduce poverty and improve health in low-income, unemployed populations.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants R01 AA12154 and T32 DA007209. The authors thank Mick Needham and Jacqueline Hampton for the efforts in implementing this experiment. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Mikhail N. Koffarnus, Center for Learning and Health, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

Conrad J. Wong, Center for Learning and Health, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

Michael Fingerhood, Center for Learning and Health, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Dace S. Svikis, Department of Clinical Psychology, Virginia Commonwealth University

George E. Bigelow, Behavioral Pharmacology Research Unit, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

Kenneth Silverman, Center for Learning and Health, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

References

- Acion L, Peterson JJ, Temple S, Arndt S. Probabilistic index: An intuitive non-parametric approach to measuring the size of treatment effects. Statistics in Medicine. 2006;25:591–602. doi: 10.1002/sim.2256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Marsch LA. Toward a behavioral economic understanding of drug dependence: Delay discounting processes. Addiction. 2001;96:73–86. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobova L, Finn PR, Rickert ME, Lucas J. Disinhibitory psychopathology and delay discounting in alcohol dependence: Personality and cognitive correlates. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2009;17:51–61. doi: 10.1037/a0014503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos JM, Scrivener S, Snipes J, Hamilton G, Schwartz C, Walter J. Improving basic skills: The effects of adult education in welfare-to-work programs. U.S. Department of Education, Office of the Under Secretary, Planning and Evaluation Service; Washington, DC: 2002. Retrieved from the Manpower Demonstration Research Corporation website: http://www.mdrc.org/publications/179/full.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Bucklin BR, Dickinson AM. Individual monetary incentives: A review of different types of arrangements between performance and pay. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management. 2001;21:45–137. doi: 10.1300/J075v21n03_03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cantwell MF, McKenna MT, McCray E, Onorato IM. Tuberculosis and race/ethnicity in the united states. impact of socioeconomic status. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1998;157:1016–1020. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.4.9704036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catania AC. Learning. interim 4. Cornwall-on-Hudson, NY: Sloan Publishing; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham LS, Kelsey JL. Epidemiology of musculoskeletal impairments and associated disability. American Journal of Public Health. 1984;74:574–579. doi: 10.2105/ajph.74.6.574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon EM, Wong CJ, Sylvest CE, Crone-Todd DE, Silverman K. Computer-based typing and keypad skills training outcomes of unemployed injection drug users in a therapeutic workplace. Substance use & Misuse. 2004;39:2325–2353. doi: 10.1081/ja-200034620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everson SA, Maty SC, Lynch JW, Kaplan GA. Epidemiologic evidence for the relation between socioeconomic status and depression, obesity, and diabetes. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2002;53:891–895. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00303-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein JS. The relationship between socioeconomic status and health: A review of the literature. The Milbank Quarterly. 1993;71:279–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green L, Myerson J, Lichtman D, Rosen S, Fry A. Temporal discounting in choice between delayed rewards: The role of age and income. Psychology and Aging. 1996;11:79–84. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.11.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton G. Moving people from welfare to work: Lessons from the national evaluation of welfare-to-work strategies. 2002 Retrieved from the Manpower Demonstration Research Corporation website: http://www.mdrc.org/publications/64/full.pdf.

- Higgins ST, Silverman K, Heil SH. Contingency management in substance abuse treatment. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan GA, Keil JE. Socioeconomic factors and cardiovascular disease: A review of the literature. Circulation. 1993;88:1973–1998. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.4.1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koffarnus MN, DeFulio A, Sigurdsson SO, Silverman K. Performance pay improves engagement, progress, and satisfaction in computer-based job skills training of low-income adults. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. doi: 10.1002/jaba.51. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koffarnus MN, Wong CJ, Diemer K, Needham M, Hampton J, Fingerhood M, Silverman K. A randomized clinical trial of a therapeutic workplace for chronically unemployed, homeless, alcohol-dependent adults. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2011;46:561–569. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agr057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magura S, Staines GL, Blankertz L, Madison EM. The effectiveness of vocational services for substance users in treatment. Substance use & Misuse. 2004;39:2165–2213. doi: 10.1081/ja-200034589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JM, Fields HL, D’Esposito M, Boettiger CA. Impulsive responding in alcoholics. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29:2158–2169. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000191755.63639.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muennig P, Fiscella K, Tancredi D, Franks P. The relative health burden of selected social and behavioral risk factors in the united states: Implications for policy. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:1758–1764. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.165019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM. Delay discounting of money and alcohol in actively using alcoholics, currently abstinent alcoholics, and controls. Psychopharmacology. 2001;154:243–250. doi: 10.1007/s002130000638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riccio J, Dechausay N, Greenberg D, Miller C, Rucks Z, Verma N. Toward reduced poverty across generations: Early findings from New York City’s conditional cash transfer program. 2010 Retrieved from the Manpower Demonstration Research Corporation website: http://www.mdrc.org/publications/64/full.pdf.

- Rounsaville BJ, Rosen M, Carroll KC. Medication compliance. In: Higgins ST, Silverman K, Heil SH, editors. Contingency management in substance abuse treatment. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 140–158. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman K. Exploring the limits and utility of operant conditioning in the treatment of drug addiction. The Behavior Analyst. 2004;27:209–230. doi: 10.1007/BF03393181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman K, Chutuape MD, Bigelow GE, Stitzer ML. Voucher-based reinforcement of attendance by unemployed methadone patients in a job skills training program. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1996;41:197–207. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(96)01252-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman K, Chutuape MD, Svikis DS, Bigelow GE, Stitzer ML. Incongruity between occupational interests and academic skills in drug abusing women. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1995;40:115–123. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman K, DeFulio A, Sigurdsson SO. Maintenance of reinforcement to address the chronic nature of drug addiction. Preventive Medicine. 2012;55:S46–S53. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman K, Kaminski BJ, Higgins ST, Brady JV. Behavior analysis and treatment of drug addiction. In: Fisher WW, Piazza HS, editors. Handbook of applied behavior analysis. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2011. pp. 451–471. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman K, Wong CJ, Grabinski MJ, Hampton J, Sylvest CE, Dillon EM, Wentland RD. A web-based therapeutic workplace for the treatment of drug addiction and chronic unemployment. Behavior Modification. 2005;29:417–463. doi: 10.1177/0145445504272600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman K, Wong CJ, Needham M, Diemer KN, Knealing T, Crone-Todd D, Kolodner K. A randomized trial of employment-based reinforcement of cocaine abstinence in injection drug users. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2007;40:387–410. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2007.40-387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpp KG, John LK, Troxel AB, Norton L, Fassbender J, Loewenstein G. Financial incentive-based approaches for weight loss. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2008;300:2631–2637. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]