ABSTRACT

Members of the bacterial order Planctomycetales have often been observed in associations with Crustacea. The ability to degrade chitin, however, has never been reported for any of the cultured planctomycetes although utilization of N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) as a sole carbon and nitrogen source is well recognized for these bacteria. Here, we demonstrate the chitinolytic capability of a member of the family Gemmataceae, Fimbriiglobus ruber SP5T, which was isolated from a peat bog. As revealed by metatranscriptomic analysis of chitin-amended peat, the pool of 16S rRNA reads from F. ruber increased in response to chitin availability. Strain SP5T displayed only weak growth on amorphous chitin as a sole source of carbon but grew well with chitin as a source of nitrogen. The genome of F. ruber SP5T is 12.364 Mb in size and is the largest among all currently determined planctomycete genomes. It encodes several enzymes putatively involved in chitin degradation, including two chitinases affiliated with the glycoside hydrolase (GH) family GH18, GH20 family β-N-acetylglucosaminidase, and the complete set of enzymes required for utilization of GlcNAc. The gene encoding one of the predicted chitinases was expressed in Escherichia coli, and the endochitinase activity of the recombinant enzyme was confirmed. The genome also contains genes required for the assembly of type IV pili, which may be used to adhere to chitin and possibly other biopolymers. The ability to use chitin as a source of nitrogen is of special importance for planctomycetes that inhabit N-depleted ombrotrophic wetlands.

IMPORTANCE Planctomycetes represent an important part of the microbial community in Sphagnum-dominated peatlands, but their potential functions in these ecosystems remain poorly understood. This study reports the presence of chitinolytic potential in one of the recently described peat-inhabiting members of the family Gemmataceae, Fimbriiglobus ruber SP5T. This planctomycete uses chitin, a major constituent of fungal cell walls and exoskeletons of peat-inhabiting arthropods, as a source of nitrogen in N-depleted ombrotrophic Sphagnum-dominated peatlands. This study reports the chitin-degrading capability of representatives of the order Planctomycetales.

KEYWORDS: Planctomycetes, Gemmataceae, Fimbriiglobus ruber, genome annotation, chitinase, chitinolytic ability

INTRODUCTION

Members of the bacterial phylum Planctomycetes are widely distributed in various aquatic and terrestrial habitats (1, 2). Three distinct orders of planctomycetes are currently recognized, namely, the Planctomycetales, Phycisphaerales, and “Candidatus Brocadiales.” Of these, a comprehensive knowledge of the metabolic potential and functional roles in the environment is available only for chemo-lithoautotrophic anammox planctomycetes of the order “Candidatus Brocadiales” (3, 4). Few currently cultured representatives of the Phycisphaerales are chemo-organotrophs, which are capable of degrading various heteropolysaccharides (5). The order Planctomycetales also accommodates chemo-organotrophic planctomycetes and includes the largest number of cultured representatives, which belong to 17 genera with validly published names. Despite the fact that this is the first described order within the phylum Planctomycetes (6), we know very little about potential functions of its members in the environment. Some of these bacteria, including Blastopirellula and Rhodopirellula-like planctomycetes, are found mostly in marine environments and represent an important part of the complex microbial biofilm community of a wide range of macroalgae (7). These planctomycetes specialize in degradation of sulfated polysaccharides produced by algae, and their genomes contain an exceptionally high number of sulfatase genes (8). Members of the family Isosphaeraceae are especially abundant in boreal peatlands (9, 10). As revealed by recent comparative genomic analysis, these peat-inhabiting planctomycetes possess extremely high but partly hidden glycolytic potential (11) and are capable of degrading various heteropolysaccharides. The ability to degrade fibrous and microcrystalline cellulose, however, has so far been demonstrated only for a single, peat-inhabiting planctomycete from the family Gemmataceae, Telmatocola sphagniphila (12). Except for participation in degradation of plant-derived polymers, planctomycetes were identified as efficient degraders of exopolysaccharides produced by other soil bacteria (13).

The ability to degrade chitin, one of the most abundant polymers in nature, has never been reported for any of the cultured planctomycetes. Given that utilization of N-acetylglucosamine as a sole carbon and nitrogen source is well recognized for these bacteria, the absence of chitinolytic capabilities looks somewhat illogical. At the same time, cells of planctomycetes have often been observed in associations with Crustacea (14–16). One of the recently described planctomycetes, “Fuerstia marisgermanicae” NH11T, was isolated from a crab shell collected on the tidal mud flat of the German Wadden Sea (17). None of these planctomycetes was shown to degrade chitin. These cultured representatives, however, do not cover all planctomycete diversity in natural habitats. Recent molecular study of microbial degradation of chitin in an agricultural soil suggested involvement of Singulisphaera-like planctomycetes in this process (18). Additional evidence for the existence of chitinolytic planctomycetes was obtained in a metatranscriptome-based study of microbial populations driving biopolymer degradation in acidic peatlands (19). Although no changes in the relative abundance of planctomycetes within the whole bacterial community were observed in response to the amendment with chitin, some groups within uncultivated planctomycetes, in particular Gemmata-like bacteria, were clearly stimulated by the availability of this biopolymer.

Recently, we described one novel member of the family Gemmataceae from acidic peat bogs, namely, Fimbriiglobus ruber SP5T (20). This planctomycete was isolated from the peat bog Obukhovskoye, which served as a source of peat material used in the metatranscriptomic study of Ivanova et al. (19). Although strain SP5T was unable to degrade chitin from crab shells, weak growth was observed on amorphous chitin prepared as described elsewhere (21). Since unambiguous detection of chitin degradation capabilities in this peat-inhabiting planctomycete was complicated by its low growth rates and high cell aggregation in laboratory medium, this study was initiated in order to determine the presence of genomic determinants for chitin degradation in this bacterium.

RESULTS

Metatranscriptome-derived evidence for the presence of chitinolytic capabilities in F. ruber.

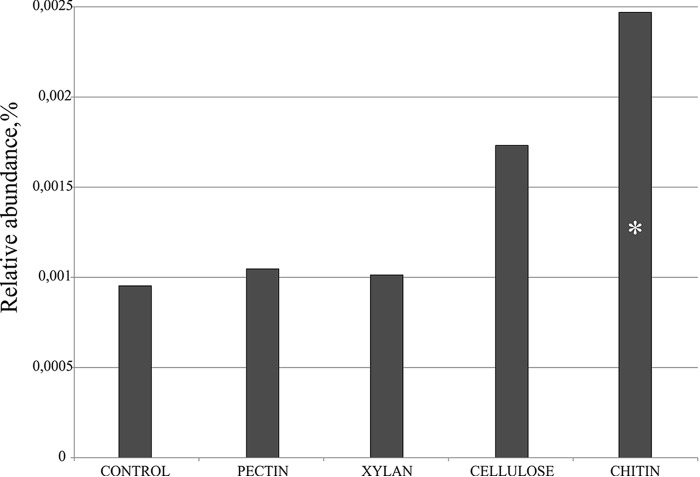

This study began with attempts to detect the substrate-induced response of F. ruber-like planctomycetes to amendment of Sphagnum-derived peat from the peat bog Obukhovskoye with chitin. For this purpose, we reanalyzed the small subunit (SSU) rRNA data set retrieved in our recent metatranscriptomic study (19), which assessed the substrate-induced response of peat-inhabiting microorganisms to amendments with various key biopolymers, including cellulose, xylan, pectin, and chitin. The 16S rRNA reads from F. ruber-like planctomycetes were sorted out using a species-level identity threshold of 97% from the sequence sets corresponding to four experimental incubations with different biopolymers and the control incubation without added substrate. As revealed by this analysis, the pool of 16S rRNA reads from F. ruber-like planctomycetes significantly increased 2.5-fold (P value of <0.01) in response to chitin availability (Fig. 1). Notably, no response was detected in incubations with pectin and xylan, while some statistically insignificant stimulation of F. ruber was also observed due to amendment of peat with cellulose. The chitinolytic potential of F. ruber, suggested by the results of metatranscriptome-based study, was further examined by the focused growth experiments with the type strain of this species, SP5T.

FIG 1.

The relative abundance values represent average values calculated by relating the number of reads assigned to the species Fimbriiglobus ruber (blast sequence identity threshold of 97%) to the total number of SSU rRNA reads retrieved from four experimental incubations of peat samples amended with different biopolymers and from the control incubation without added substrate in the study of Ivanova et al. (19). The relative abundance values represent averages of triplicate data sets (pectin, cellulose, and xylan) or duplicate data sets (chitin and control). A significant difference in Ribo-tag abundances between control and biopolymer-amended samples is indicated by an asterisk (P < 0.01).

Growth on chitin and chitinolytic activities.

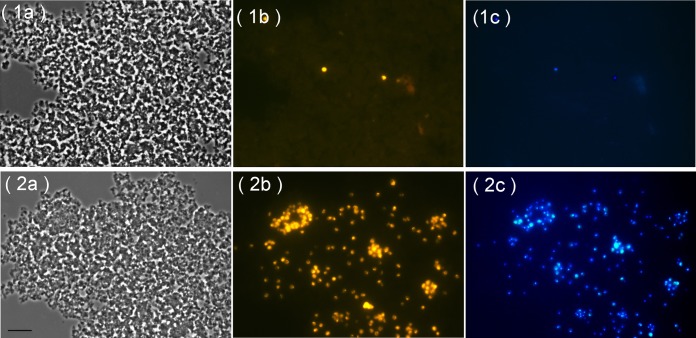

Two types of substrate utilization tests were performed with F. ruber SP5T. One of them corresponded to the routinely used assay in which chitin is provided as a sole source of carbon, while (NH4)2SO4 is supplied as a source of nitrogen. In the second type of growth experiments, chitin was added as the only source of nitrogen, while glucose served as the source of carbon. Microscopic examination of the respective cultures after 1 month of incubation revealed cells of strain SP5T being attached to microparticles of amorphous chitin (Fig. 2); free-floating cells were absent. Only a very few rarely scattered cells of strain SP5T were observed in cultures with amorphous chitin as a sole source of carbon (Fig. 2, frames 1a to 1c). In contrast, all microparticles of chitin were densely colonized by planctomycete cells in cultures containing chitin as a source of nitrogen (Fig. 2, frames 2a to 2c). Cell counting revealed the drastic difference by two orders of magnitude in cell abundances in these two types of incubations (Table 1), suggesting that the activity of chitin degradation is largely dependent on the presence of an easily available carbon source.

FIG 2.

Specific detection of planctomycete cells on microparticles of amorphous chitin used in growth experiments as a source of carbon (row 1) or nitrogen (row 2). Phase-contrast images (a frames), the respective epifluorescent micrographs of whole-cell hybridizations with Cy3-labeled probes PLA46-PLA886 (b frames), and DAPI staining (c frames) are shown. Bar, 10 μm.

TABLE 1.

Cell numbers of Fimbriiglobus ruber SP5T after 30 days of incubation with chitin as a source of carbon or nitrogen

| Incubation no. | Growth of F. ruber by condition (no. of cells/ml [×108])a |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chitin as a source of C |

Chitin as a source of N |

|||

| Chitin + NH4+ | Control (+NH4+)b | Chitin + glucose | Control (+glucose)b | |

| 1 | 2.2 ± 0.6 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 150 ± 1.6 | 22 ± 5 |

| 2 | 4.1 ± 2.3 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 248 ± 0.3 | 13 ± 7 |

| 3 | 2.1 ± 0.9 | 1.8 ± 0.4 | 180 ± 0.2 | 13 ± 5 |

The results of three independent incubations (1 to 3) are shown. Values are the average ± standard error.

Control experiments did not include chitin.

Chitinolytic activities of F. ruber SP5T with synthetic soluble substrates were detected in cell extracts. Activity was maximal with the β-N-acetylglucosaminidase substrate 4-methylumbelliferyl (MU)-N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminide (31.5 U/mg), while about 24-fold-lower activity was observed with 4-MU-diacetyl-β-d-chitobioside (1.3 U/mg), and about 40-fold-lower activity was recorded with the endochitinase substrate 4-MU-β-d-N,N′,N″-triacetylchitotriose (0.8 U/mg). Further insight into the metabolic potential of F. ruber SP5T was made via the genome analysis.

Genome characteristics.

The genome of F. ruber SP5T was sequenced using a combination of pyrosequencing and PacBio single-molecule real-time sequencing technique. Combined assembly of the sequencing reads obtained by two techniques yielded 20 contigs with N50 contig size of 1,426,550 bp. The size of the F. ruber SP5T genome, estimated as a total length of all contigs, is 12,363,577 bp, with a GC content of 64.2%. To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest genome of planctomycetes sequenced to date. Annotation of the genome sequence revealed 10,640 potential protein-coding genes, of which 4,693 (44%) can be functionally assigned; 2,636 genes are unique to F. ruber SP5T with no significant similarity to any known sequences.

Metabolism and cell biology.

KEGG-based annotation of the F. ruber SP5T genome sequence classified 2,086 proteins into 23 major functional categories. The genes encoding metabolic pathways common for chemo-organotrophic bacteria, such as glycolysis, the citrate cycle, the pentose-phosphate pathway, and oxidative phosphorylation, were present in the genome of F. ruber SP5T. This planctomycete has the genomic potential for synthesis of all amino acids. The number of ABC-transporters in F. ruber SP5T is 52, which is comparable to the calculated mean of 49 ABC-transporters in free-living prokaryotes (8). Also, two fructose-type sugar-specific subunits of the phosphotransferase system could be found in strain SP5T.

The survey for genes related to cell division revealed that the FtsZ-encoding gene was absent, while two copies of the gene coding for FtsK, the DNA translocase, were present in the genome of F. ruber SP5T. The cytoskeletal protein MreB, whose gene has a patchy presence among the planctomycetes and is absent in Gemmataceae planctomycetes (22), is present in F. ruber SP5T. Several, but not all, genes involved in peptidoglycan biosynthesis, including murA, murB, murE, and murF, were detected (23).

Recently, the gene encoding the key enzyme for synthesis of N-methylated phosphorus-free ornithine membrane lipids, N-methyltransferase (OlsG), was identified in the genome of Singulisphaera acidiphila DSM 18658T (Sinac_1600) (24) and later detected in genomes of other members of the family Isosphaeraceae (11). Our analysis revealed that distant homologs of Sinac_1600 are also present in the genomes of Gemmataceae planctomycetes, including F. ruber SP5T, Zavarzinella formosa A10T, and Gemmata sp. strain SH-PL17.

The examination of the F. ruber SP5T genome for the presence of giant genes (25) revealed 69 genes with a size of >5 kb, among which 10 genes exceed 10 kb and 1 gene exceeds 25 kb. The functions of these giant genes remain enigmatic. So far, the highest number (60) of giant genes with a size of >5 kb was recorded for another member of the family Gemmataceae, Zavarzinella formosa A10T (17).

Genetic background of chitinolytic capability.

Analysis of the F. ruber SP5T genome revealed several enzymes that could potentially be involved in chitin utilization. The extracellular hydrolysis of chitin could be performed by FRUB_0131 endochitinase. This glycoside hydrolase (GH) family 18 (GH18) enzyme carries an N-terminal Sec secretion signal, suggesting its extracellular operation. GenBank searches revealed similar proteins (37 to 46% amino acid sequence identity) in only three planctomycetes, including Planctomicrobium piriforme DSM 26348T, Planctomyces sp. strain SH-PL14 and Phycisphaerae bacterium ST-NAGAB-D1. Planctomicrobium piriforme was described as being incapable of growth on chitin (26), while the two other planctomycetes have not been characterized phenotypically.

For functional analysis of the predicted chitinase FRUB_0131, the corresponding gene coding for mature protein lacking an N-terminal signal peptide was expressed in E. coli. The recombinant enzyme was purified to homogeneity through Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) affinity chromatography. Chitinolytic activities of recombinant FRUB_0131 were evaluated with synthetic soluble substrates. The maximal activity (4.64 U/mg) was observed with the endochitinase substrate 4-MU-β-d-N,N′,N″-triacetylchitotriose, while lower values were detected with 4-MU-diacetyl-β-d-chitobioside (0.55 U/mg) and 4-MU-N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminide (0.16 U/mg). This substrate specificity pattern is consistent with the predicted endochitinase activity of FRUB_0131.

The search for other chitin-degrading enzymes from GH families 18, 19, and 20, carrying an N-terminal signal peptide, revealed only GH20 family protein FRUB_4986. This enzyme, annotated as β-hexosaminidase, could cleave N-acetyl-d-glucosamine (GlcNAc) from the nonreducing end of the soluble chitin oligomers (27), produced by FRUB_0131 endochitinase. A blastp search against the GenBank database revealed similar enzymes in some members of the Verrucomicrobia (up to 44% sequence identity) and only more distant homologs in the genomes of various planctomycetes. FRUB_4986 hydrolase could be responsible for the high level of acetylglucosaminidase activity described above. Concerted activity of endochitinase FRUB_0131 and putative β-N-acetylglucosaminidase FRUB_4986 could result in hydrolysis of chitin to oligomers and subsequent production of GlcNAc monomers.

One more gene, FRUB_5329, encodes a 758-amino-acid (aa) protein with a calculated molecular mass of 78.6 kDa. It comprises two copies of a carbohydrate-binding CBM2 domain and a single ChiA-like (cd06543) catalytic domain of GH18 family hydrolases at the C terminus. CBM2 typically binds cellulose but several of these modules have been shown to also bind chitin (28). Although SignalP, version 4.1, did not convincingly reveal an N-terminal secretion signal, the presence of carbohydrate-binding domains suggests that this enzyme could be also extracellular. The blastp search against GenBank revealed no proteins with the same domain architecture although hydrolases with similar catalytic domains (amino acid sequence identity up to 52%) were found among Actinobacteria. Notably, homologous enzymes are missing in other planctomycetes. Therefore, acquisition of this enzyme in F. ruber SP5T by lateral transfer seems to be plausible.

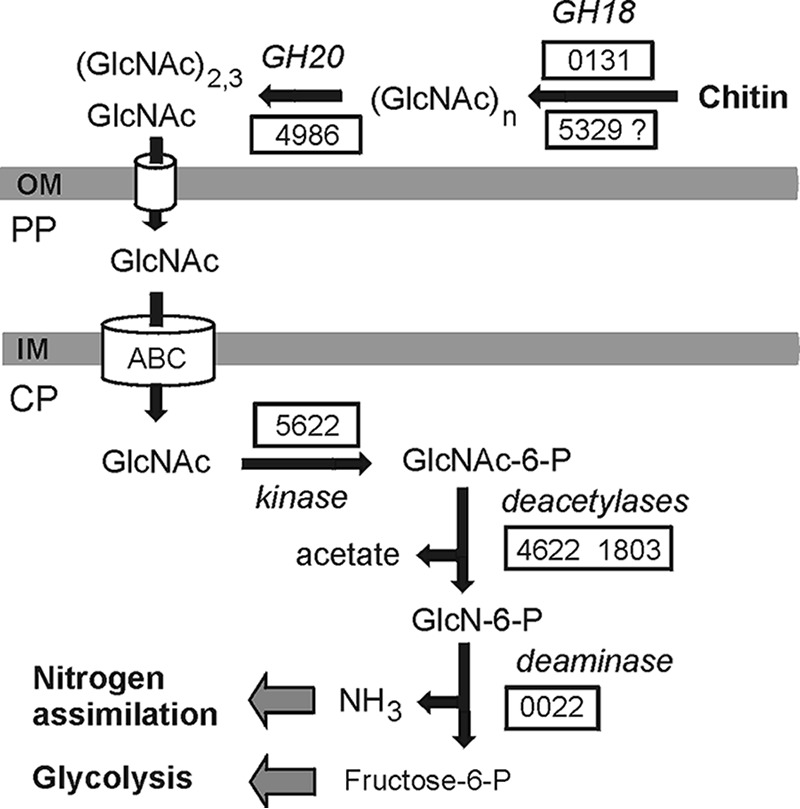

GlcNAc may be imported into the cytoplasm by ABC-type transporters (29). In the cytoplasm, GlcNAc may be phosphorylated to yield GlcNAc-6-P by N-acetylglucosamine kinase (FRUB_5622). Then, GlcNAc-6-P could be deacetylated by N-acetylglucosamine-6-phosphate deacetylase (FRUB_4622 and FRUB_1803) yielding glucosamine 6-phosphate. The latter is converted via the action of glucosamine-6-phosphate deaminase (FRUB_0022) into fructose-6-P that enters central glycolytic pathway (30) (Fig. 3). GenBank searches revealed enzymes similar to GlcNAc kinase, GlcNAc-6-P deacetylases, and GlcN-6-P deaminase in members of the order Planctomycetales.

FIG 3.

Suggested scheme of chitin degradation in F. ruber SP5T. Enzymes are given with gene numbers corresponding to those from the genome of F. ruber SP5T when possible. Abbreviations: OM, outer membrane; PP, periplasm; CP, cytoplasm; GH18, GH18 family chitinase; GH20, GH20 family β-N-acetylglucosaminidase; ABC, ABC-type sugar transporter.

While analyzing the genome, we did not find enzymes responsible for intracellular metabolism of GlcNAc dimers in chitinolytic bacteria such as Chitinispirillum alkaliphilum (21), e.g., N,N′-diacetylchitobiose phosphorylase that can hydrolyze chitobiose and generate GlcNAc and GlcNAc-1-P and acetylglucosamine-1-P-mutase making GlcNAc-6-P from GlcNAc-1-P. The lack of these components of the chitinolytic pathway seems to limit the ability of F. ruber SP5T to grow on chitin since only N-acetylglucosamine could be metabolized. Taking into account the lack of a N2 fixation pathway in the genome of F. ruber SP5T, one could suggest that chitin may primarily serve as a source of ammonium generated by deamination of glucosamine-6-phosphate.

Degradation of other polysaccharides.

In the original description, F. ruber was reported to be capable of growth on several polysaccharides, such as xylan, laminarin, lichenan, starch, and xanthan, while cellulose and pectin were not utilized (20). These metabolic capabilities of strain SP5T were reevaluated by measuring the hydrolysis of the respective polysaccharides by lysed cell extracts. Carboxymethyl cellulose, xanthan, laminarin, lichenan, and xylan were efficiently hydrolyzed, while activities toward starch and microcrystalline cellulose were not observed (Fig. 4A).

FIG 4.

Hydrolytic activities of F. ruber SP5T crude cell extract. (A) Hydrolysis of different polysaccharides evaluated by measuring the amounts of total reduced sugars released after treatment. The following substrates were tested: lane 1, microcrystalline cellulose; lane 2, starch; lane 3, carboxymethyl cellulose; lane 4, lichenan; lane 5, laminarin; lane 6, xanthan; lane 7, birchwood xylan; lane 8, beechwood xylan. (B) Hydrolysis of aryl glycosides. The following substrates were tested: lane 1, pNPGal; lane 2, pNPXyl; lane 3, pNPMan; lane 4, pNPGlu. Data represent the means of three separate experiments. The activities of the cell extract with carboxymethyl cellulose (A) and pNPGlu (B) were defined as 100%.

Hydrolytic activities in the cell extracts were also assayed using p-nitrophenyl (pNP) glycosides. The highest activity was observed with p-nitrophenyl-β-d-glucopyranoside (β-glucosidase substrate), followed by nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (β-galactosidase substrate), p-nitrophenyl-β-d-xylopyranoside (β-xylosidase substrate), and pNP-β-d-mannopyranoside (β-mannosidase substrate), as shown in Fig. 4B.

Analysis of the F. ruber SP5T genome revealed 11 genes encoding glycoside hydrolases predicted to have N-terminal signal peptides and thus possibly involved in extracellular hydrolysis of polysaccharides. Despite the reported inability of F. ruber to utilize cellulose, its genome encodes two signal peptide-containing GH5 family glycosyl hydrolases, annotated as endo-1,4-β-glucanases (FRUB_3928 and FRUB_8601). These enzymes could be responsible for extracellular hydrolysis of cellulose, while intracellular hydrolysis of produced cellobiose could be performed by GH94 family cellobiose phosphorylase (FRUB_8916). In contrast, no apparent endo-1,4-β-xylanases were identified although hydrolytic activity toward xylan was observed, and strain SP5T was able to grow on this substrate. It is possible that GH5 enzymes could be responsible for hydrolysis of xylan since a number of activities were reported for this family, including endoglucanase, endomannanase, β-glucosidase, β-mannosidase, and xylanase (31). The ability to utilize xylose is consistent with the presence of the isomerase pathway of xylose metabolism, including xylose isomerase (FRUB_2606) and xylulose kinase (FRUB_3023).

Several other signal peptide-containing glycosyl hydrolases could be responsible for extracellular hydrolysis of polysaccharides. The GH99 family enzyme FRUB_7797 could exhibit endo-α-mannosidase and/or endo-α-1,2-mannanase activity, while β-galactosidase, β-glucuronidase, β-mannosidase, and exo-β-glucosaminidase activities were described for GH2 hydrolases (FRUB_5004 and FRUB_5438). Alpha-N-arabinofuranosidase FRUB_9125 could catalyze the hydrolysis of nonreducing terminal alpha-l-arabinofuranosidic linkages in arabinoxylans and arabinogalactans. Specificity of several other extracellular glycosyl hydrolases could not be reliably predicted (FRUB_0231, FRUB_0245, FRUB_2479, FRUB_3476, and FRUB_8423).

Despite the reported ability of F. ruber to utilize starch, genome analysis revealed no candidate enzymes for extracellular hydrolysis of this polysaccharide. Consistently, no hydrolytic activity toward starch was detected in cell extracts (Fig. 4A). Although the GH15 family glucoamylase (FRUB_8812) and two GH77 family amylomaltases (FRUB_5679 and FRUB_6807) are encoded, they lack a signal peptide and most likely are involved in intracellular pathways of the synthesis and degradation of storage polysaccharides.

Type IV pili.

In agreement with the morphology of F. ruber SP5T cells, which are covered by numerous fimbriae, a complete set of genes for type IV pilus-based twitching motility is present in the genome, including pilins (Flp), assembly ATPase (PilB/TadA), inner membrane core proteins (PilC/TadB and TadC), prepilin peptidase (PilD/TadV), outer membrane secretin (PilQ/RcpA), retraction ATPase (PilT), inner membrane proteins (PilM, PilN, and PilO), and regulatory proteins. These pili may be used by F. ruber to adhere and move around chitin and possibly other polysaccharide substrates similar to the way some cellulolytic bacteria adhere to cellulose (32, 33) and Vibrio parahaemolyticus adheres to chitin (34). However, no close homologs of GlcNAc binding protein A (GbpA), which has been reported to mediate bacterial attachment to both chitin and mammalian intestinal mucin in Vibrio sp. (35), were found.

Secondary metabolite-related genes.

Genome mining of gene clusters that encode biosynthetic pathways for secondary metabolites in F. ruber SP5T revealed 10 clusters (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Five clusters encode polyketide synthases (PKS) of type I and others. The closest gene homologs to PKS clusters from F. ruber SP5T belong to the planctomycetes Singulisphaera acidiphila DSM 18658T, Isosphaera pallida ATCC 43644T, Gemmata obscuriglobus UQM 2246T, and the proteobacterium Pelobacter propionicus DSM 2379. The other five clusters encode terpene-like compounds. Their closest homologs also belong to several planctomycetes such as S. acidiphila DSM 18658T and G. obscuriglobus UQM 2246T and an uncharacterized member of the phylum Bacteroidetes (Fig. S1).

DISCUSSION

While the ability to utilize N-acetylglucosamine as a carbon and nitrogen source is widely distributed in members of the order Planctomycetales, the ability to degrade chitin, a natural source of this substrate, is described only for F. ruber SP5T. These observations are consistent with the distribution of homologs of F. ruber SP5T genes relevant to chitin metabolism in various bacterial taxa. Close homologs of enzymes required for utilization of GlcNAc (GlcNAc kinase, GlcNAc-6-P deacetylase, and GlcN-6-P deaminase) in F. ruber SP5T are encoded in the genomes of many planctomycetes, as could be expected. In contrast, enzymes similar to GH18 family chitinases (FRUB_0131 and FRUB_5329) and GH20 family β-N-acetylglucosaminidase (FRUB_4986) are either absent in other planctomycetes or present in only a few species (see Fig. S2A to C in the supplemental material) and seem to be laterally acquired in F. ruber SP5T. Interestingly, these three genes are located in different genome regions and, most likely, were obtained in independent transfer events. Each of these transfers is expected to enhance the chitinolytic capabilities of the recipient, facilitating extracellular hydrolysis of chitin with production of N-acetylglucosamine that enters the already existing metabolic pathway.

The ability to use chitin as a source of nitrogen is of special importance for planctomycetes that inhabit Sphagnum peat bogs. These ecosystems receive all nutrient inputs solely from the atmosphere and are, therefore, nutrient poor by nature (36, 37). Peat water usually contains very low concentrations of NH4+ and NO3− (3 to 100 μM) (38–40). As a consequence, many bacteria that thrive in peat bogs are capable of N2 fixation (41). Given the lack of dinitrogen fixation capabilities in members of the order Planctomycetales, they should either stay in a close association with N2-fixing bacteria or rely on degradation of N-containing biopolymers. Apparently, F. ruber uses the second strategy and obtains required nitrogen from chitin, a major constituent of fungal cell walls and exoskeletons of peat-inhabiting arthropods. It may well be that many planctomycetes from Sphagnum peat bogs or other nitrogen-poor habitats possess similar metabolic capabilities. This possibility, however, cannot be verified at present since only a few genomes from peat-inhabiting planctomycetes are currently available. One suitable target for further growth experiments and enzymatic analyses is Planctomicrobium piriforme, which was isolated from a littoral wetland of a boreal lake (26). The original description of this planctomycete reports its inability to degrade chitin. This characteristic, however, was assessed in a routine test by providing chitin as a source of carbon and needs to be reevaluated using several alternative experimental settings.

As revealed in our study, the conventional growth tests for the presence of chitinolytic capabilities in bacteria may not be fully suitable for planctomycetes. In the case of F. ruber SP5T, growth on chitin as a sole source of carbon was nearly nondetectable due to the relatively low endochitinase activity. However, growth with this biopolymer was clearly enhanced in the presence of an easily utilizable carbon substrate. It is tempting to speculate that, in habitats depleted of nitrogen but rich in organic carbon, such as peat bogs, chitin is used by planctomycetes primarily as a source of nitrogen. As becomes apparent from the recent studies, planctomycetes are more involved in the processes of biopolymer degradation in various habitats than previously thought. They also seem to possess an unusual mechanism of high-molecular-weight polysaccharide uptake, being capable of taking up and accumulating macromolecules in the periplasmic space (42, 43). This mechanism gives a clear ecological advantage to slow-growing planctomycetes by securing substantial quantities of substrate in the cell (43). Whether this adaptation feature is common for peat-inhabiting planctomycetes remains to be verified.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Analysis of metatranscriptome-derived data.

The SSU rRNA data set retrieved in the study of Ivanova et al. (19) was used to analyze the abundance of F. ruber-like planctomycetes in Sphagnum-derived peat and the substrate-induced response of these bacteria to amendments with different biopolymers. The 16S rRNA gene sequence of F. ruber SP5T was used as a query for blastn search via blast+ (44) among the SSU rRNA reads with an identity threshold of 97%. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett's multiple-comparison test (i.e., comparison of the results obtained for biopolymer-amended samples with those of the control samples) was performed using GraphPad Prism, version 6.00, for Windows (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Tests were considered significant if they had a P value of <0.05.

Growth experiments and whole-cell hybridization.

F. ruber SP5T (also LMG 29572T or VKM B-3045T) was grown under static conditions at 25°C in 160-ml serum bottles containing 10 ml of liquid medium M1 containing the following (per liter of distilled water): 0.1 g of KH2PO4, 0.1 g of MgSO4 × 7H2O, 0.02 g of CaCl2 × 2H2O, 1 ml of trace element solution “44,” and 1 ml of Staley's vitamin solution (45), pH 4.8 to 5.5. Amorphous chitin was prepared as described elsewhere (21) and added to the medium at a concentration of 0.1% (wt/vol). In one set of experimental flasks, chitin was provided as a sole source of carbon, while (NH4)2SO4 (0.01%, wt/vol) was supplied as a source of nitrogen. In the second set of incubation flasks, chitin was added as the only source of nitrogen, while glucose (0.5 g liter−1) served as the source of carbon. Control incubations without chitin (Table 1) were run in parallel under the same conditions. All incubations were performed in triplicate. After 30 days of incubation, the culture suspensions were fixed with 4% (wt/vol) freshly prepared paraformaldehyde solution as described by Dedysh et al. (47). A combination of two Planctomycetes-specific Cy3-labeled oligonucleotide probes, PLA46 (5′-GACTTGCATGCCTAATCC-3′) and PLA886 (5′-GCCTTGCGACCATACTCCC-3′) (46), was applied for specific detection of cells on microparticles of chitin. The oligonucleotide probes were purchased from Syntol (Moscow, Russia). Hybridization was done on gelatin-coated (0.1%, wt/vol) and dried Teflon-laminated slides (MAGV, Germany) with eight wells for independent positioning of the samples. The fixed samples were applied to these wells, hybridized to the corresponding fluorescent probes, and stained with the universal DNA stain 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; 1 μM) as described earlier (47). The cell counts were carried out with a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) equipped with Zeiss filters 20 and 02 for Cy3-labeled probes and DAPI staining, respectively. Cell counting was performed on 100 randomly chosen fields of view (FOV) for each test sample. The number of target cells per milliliter of culture suspension was determined from the area of the sample spot, the FOV area, and the volume of the fixed aliquot used for hybridization.

For genome analysis, F. ruber SP5T was grown in shaking liquid cultures at 25°C in medium M31 containing the following (per liter of distilled water): 1.0 g of N-acetylglucosamine, 0.5 g of glucose, 0.1 g of peptone, 0.1 g of yeast extract, 0.1 g of KH2PO4, and 20 ml Hunter's basal salts, pH 5.5 to 5.8. After 3 weeks of incubation, the biomass was collected and used for DNA extraction using SDS-cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) (48).

Genome sequencing, annotation, and analysis.

Sequencing of a shotgun genome library on a Roche GS FLX genome sequencer using the titanium protocol (Roche, Switzerland) resulted in the generation of ∼185 Mb of sequences with an average read length of 554 bp. A 10-kb genomic DNA library was prepared and sequenced on a PacBio RSII sequencer. Sequences totaling 698 Mb were obtained with an average read length of 3,655 bp. GS FLX reads were assembled using GS De Novo Assembler, version 3.0, and then a hybrid assembly of raw PacBio subreads and GS FLX large contigs was done using Canu (49). To test Canu results for misassemblies, we also generated a hybrid assembly using DBG2OLC (50). The two assemblies were compared and merged.

Gene search and annotation were performed using the RAST server (51), followed by manual correction. Signal peptides were predicted using Signal P, version 4.1, for Gram-negative bacteria (DTU Bioinformatics, Lyngby, Denmark [http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/]).

The analysis of F. ruber SP5T genome sequence using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) was performed by applying the GhostKOALA tool (52). Screening for secondary metabolite-related genes was performed using the online web server antiSMASH3.0.5 (Antibiotics and Secondary Metabolites Analysis SHell) (53–55).

Hydrolytic activity assays.

Chitinolytic activities of F. ruber SP5T cell extracts were measured in a fluorimetric assay with 4-methylumbelliferyl (4-MU) derivatives using a chitinase assay kit (CS1030; Sigma). Cells were collected by centrifugation and lysed by sonication. The following substrates were used: 4-MU-β-D-N,N′,N″-triacetylchitotriose, 4-MU-diacetyl-β-d-chitobioside, and 4-MU-N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminide. Assays were performed at 25°C in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0).

The enzymatic hydrolysis liberates 4-MU. The fluorescence of liberated 4-MU is measured using a fluorimeter with excitation at 360 nm and emission at 450 nm. One unit of activity was defined as the amount of protein (total cell extract) required to release 1 nmol of 4-MU from the appropriate substrate per minute under described conditions.

The hydrolytic activities of strain SP5T lysed cell extracts with amorphous chitin (prepared as described by Sorokin et al. [21]), starch (S2004; Sigma), microcrystalline cellulose (310697; Aldrich), carboxymethyl cellulose (21900; Fluka), lichenan (L6133; Sigma), laminarin (L9634; Sigma), xanthan (G1253; Sigma), birchwood xylan (X0502; Sigma), and beechwood xylan (38500; Serva) were evaluated by measuring the amounts of total reduced sugars released after treatment by the DNS method (56). Cells were collected by centrifugation and lysed by sonication. Assays were performed at 25°C in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0). Substrates were used at the following concentrations (wt/vol): amorphous chitin, 1%; carboxymethyl cellulose, 1%; microcrystalline cellulose, 1%; starch, 1%; birchwood xylan, 1%; beechwood xylan, 1%; lichenan, 1%; laminarin, and 1%; xanthan, 0.5%.

The hydrolytic activities of strain SP5T lysed cell extracts were also determined using p-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (pNPGal), p-nitrophenyl-β-d-xylopyranoside (pNPXyl), pNP-β-d-mannopyranoside (pNPMan), and p-nitrophenyl-β-d-glucopyranoside (pNPGlu). The reactions were performed with 2.3 mM each substrate in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) at 25°C. The activity was measured by release of p-nitrophenyl at 420 nm.

Expression of recombinant endochitinase FRUB_0131 and verification of its functional activity.

The gene FRUB_0131 was amplified from F. ruber genomic DNA by PCR using primers FIM0131F (5′-CGGGATCCGCGGCCGAGCCGCCCG-3′) and FIM0131R (5′-GCCTGCAGTTACCGCTTTTGCCGGCTC-3′). The resulting PCR products were digested with BamHI and PstI and inserted into pQE80 (Qiagen) at BamHI and PstI sites, yielding the plasmid pQE80-FRUB_0131. This plasmid was transformed into Escherichia coli strain DLT1270. The recombinant strain was grown at 37°C in LB medium supplemented with ampicillin and induced to express recombinant enzyme by adding isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to a final concentration of 1.0 mM at an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of approximately 0.5 and incubated further at 37°C for 3 h.

Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 3,500 × g for 15 min at 4°C and resuspended in 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.5), 0.3 M NaCl, and 5 mM imidazole. The cell extracts after sonication were centrifuged (15,000 × g, 4°C, 30 min), and the recombinant proteins from the supernatant were purified by metal affinity chromatography using a Ni-NTA spin kit (Qiagen). Upon elution from the column, the proteins were dialyzed on a Slide-A-Lyzer Mini dialysis unit (Thermo Scientific) against 12.5 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) at 4°C for 3 h (molecular mass cutoff, 3.5 kDa).

Hydrolytic activities of recombinant enzyme FRUB_0131 were analyzed using 4-MU-β-d-N,N′,N″-triacetylchitotriose, 4-MU-diacetyl-β-d-chitobioside, and 4-MU-N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminide. Assays were performed at 25°C in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.6) as described above for strain SP5T lysed cell extracts. The protein sample obtained from E. coli strain DLT1270 following the same protocol was used as a negative control in all assays.

Accession number(s).

The annotated genome sequence of F. ruber SP5T has been deposited in the DDBJ/ENA/GenBank database under accession number NIDE00000000.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (project number 16-14-10210).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02645-17.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fuerst JA. 1995. The Planctomycetes: emerging models for microbial ecology, evolution and cell biology. Microbiology 141:1493–1506. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-7-1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ward NL. 2010. Phylum XXV. Planctomycetes Garrity and Holt 2001, 137 emend. Ward, p 879–925. In Krieg NR, Staley JT, Brown DR, Hedlund BP, Paster BJ, Ward NL, Ludwig W, Whitman WB (ed), Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology, vol 4 Springer, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strous M, Fuerst JA, Kramer EH, Logemann S, Muyzer G, van de Pas-Schoonen KT, Webb R, Kuenen JG, Jetten MS. 1999. Missing lithotroph identified as new planctomycete. Nature 400:446–449. doi: 10.1038/22749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jetten MSM, Niftrik LV, Strous M, Kartal B, Keltjens JT, Op den Camp HJM. 2009. Biochemistry and molecular biology of anammox bacteria. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 44:65–84. doi: 10.1080/10409230902722783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fukunaga Y, Kurahashi M, Sakiyama Y, Ohuchi M, Yokota A, Harayama S. 2009. Phycisphaera mikurensis gen. nov., sp. nov., isolated from a marine alga, and proposal of Phycisphaeraceae fam. nov., Phycisphaerales ord. nov. and Phycisphaerae classis nov. in the phylum Planctomycetes. J Gen Appl Microbiol 55:267–275. doi: 10.2323/jgam.55.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schlesner H, Stackebrandt E. 1986. Assignment of the genera Planctomyces and Pirella to a new family Planctomycetaceae fam. nov. and description of the order Planctomycetales ord. nov. Syst Appl Microbiol 8:174–176. doi: 10.1016/S0723-2020(86)80072-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lage OM, Bondoso J. 2014. Planctomycetes and macroalgae, a striking association. Front Microbiol 5:1–9. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glöckner FO, Kube M, Bauer M, Teeling H, Lombardot T, Ludwig W, Gade D, Beck A, Borzym K, Heitmann K, Rabus R, Schlesner H, Amann R, Reinhardt R. 2003. Complete genome sequence of the marine planctomycete Pirellula sp. strain 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:8298–8303. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1431443100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Serkebaeva YM, Kim Y, Liesack W, Dedysh SN. 2013. Pyrosequencing-based assessment of the bacteria diversity in surface and subsurface peat layers of a northern wetland, with focus on poorly studied phyla and candidate divisions. PLoS One 8:e63994. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moore EK, Villanueva L, Hopmans EC, Rijpstra WIC, Mets A, Dedysh SN, Sinninghe Damsté JS. 2015. Abundant trimethylornithine lipids and specific gene sequences are indicative of planctomycete importance at the oxic/anoxic interface in Sphagnum-dominated northern wetlands. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:6333–6344. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00324-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ivanova AA, Naumoff DG, Miroshnikov KK, Liesack W, Dedysh SN. 2017. Comparative genomics of four Isosphaeraceae planctomycetes: a common pool of plasmids and glycoside hydrolase genes shared by Paludisphaera borealis PX4T, Isosphaera pallida IS1BT, Singulisphaera acidiphila DSM 18658T, and strain SH-PL62. Front Microbiol 8:412. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kulichevskaya IS, Serkebaeva YM, Kim Y, Rijpstra WIC, Sinninghe Damsté JS, Liesack W, Dedysh SN. 2012. Telmatocola sphagniphila gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel dendriform planctomycete from northern wetlands. Front Microbiol 3:146. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang X, Sharp CE, Jones GM, Grasby SE, Brady AL, Dunfield PF. 2015. Stable-isotope-probing identifies uncultured planctomycetes as primary degraders of a complex heteropolysaccharide in soil. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:4607–4615. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00055-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Staley JT. 1973. Budding bacteria of the Pasteuria – Blastobacter group. Can J Microbiol 19:609–614. doi: 10.1139/m73-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fuerst JA, Sambhi SK, Paynter JL, Hawkins JA, Atherton JG. 1991. Isolation of a bacterium resembling Pirellula species from primary tissue culture of the giant tiger prawn (Penaeus monodon). Appl Environ Microbiol 57:3127–3134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fuerst JA, Gwilliam HG, Lindsay M, Lichanska A, Belcher C, Vickers JE, Hugenholtz P. 1997. Isolation and molecular identification of planctomycete bacteria from postlarvae of the giant tiger prawn, Penaeus monodon. Appl Environ Microbiol 63:254–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kohn T, Heuer A, Jogler M, Vollmers J, Boedeker C. 2016. Fuerstia marisgermanicae gen. nov., sp. nov., an unusual member of the phylum Planctomycetes from the German Wadden Sea. Front Microbiol 7:2079. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.02079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wieczorek A, Hetz S, Kolb S. 2014. Microbial responses to chitin and chitosan in oxic and anoxic agricultural soil slurries. Biogeosciences 11:3339–3352. doi: 10.5194/bg-11-3339-2014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ivanova AA, Wegner CE, Kim Y, Liesack W, Dedysh SN. 2016. Identification of microbial populations driving biopolymer degradation in acidic peatlands by metatranscriptomic analysis. Mol Ecol 25:4818–4835. doi: 10.1111/mec.13806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kulichevskaya IS, Ivanova AA, Baulina OI, Rijpstra WIC, Sinninghe Damsté JS, Dedysh SN. 2017. Fimbriiglobus ruber gen. nov., sp. nov., a Gemmata-like planctomycete from Sphagnum peat bog and the proposal of Gemmataceae fam. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 67:218–224. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.001598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sorokin DY, Gumerov VM, Rakitin AL, Beletsky AV, Sinninghe Damsté JS, Muyzer G, Mardanov AV, Ravin NV. 2014. Genome analysis of Chitinivibrio alkaliphilus gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel extremely haloalkaliphilic anaerobic chitinolytic bacterium from the candidate phylum Termite Group 3. Environ Microbiol 16:1549–1565. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rivas-Marín E, Canosa I, Devos DP. 2016. Evolutionary cell biology of division mode in the bacterial Planctomycetes-Verrucomicrobia-Chlamydiae superphylum. Front Microbiol 7:1964. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jeske O, Schüler M, Schumann P, Schneider A, Boedeker C, Jogler M, Bollschweiler D, Rohde M, Mayer C, Engelhardt H, Spring S, Jogler C. 2015. Planctomycetes do possess a peptidoglycan cell wall. Nat Commun 6:7116. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Escobedo-Hinojosa WI, Vences-Guzmán MÁ, Schubotz F, Sandoval-Calderón M, Summons RE, López-Lara IM, Geiger O, Sohlenkamp C. 2015. OlsG (Sinac_1600) is an ornithine lipid N-methyltransferase from the planctomycete Singulisphaera acidiphila. J Biol Chem 290:15102–15111. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.639575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reva O, Tümmler B. 2008. Think big—giant genes in bacteria. Environ Microbiol 10:768–777. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kulichevskaya IS, Ivanova AA, Detkova EN, Rijpstra WI, Sinninghe Damsté JS, Dedysh SN. 2015. Planctomicrobium piriforme gen. nov., sp. nov., a stalked planctomycete from a littoral wetland of a boreal lake. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 65:1659–1665. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.000154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scigelova M, Crout DH. 1999. Microbial beta-N-acetylhexosaminidases and their biotechnological applications. Enzyme Microb Technol 25:3–14. doi: 10.1016/S0141-0229(98)00171-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hashimoto H. 2006. Recent structural studies of carbohydrate-binding modules. Cell Mol Life Sci 63:2954–2967. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6195-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li X, Roseman S. 2004. The chitinolytic cascade in vibrios is regulated by chitin oligosaccharides and a two-component chitin catabolic sensor/kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:627–631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307645100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beier S, Bertilsson S. 2013. Bacterial chitin degradation—mechanisms and ecophysiological strategies. Front Microbiol 4:149. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aspeborg H, Coutinho PM, Wang Y, Brumer H, Henrissat B. 2012. Evolution, substrate specificity and subfamily classification of glycoside hydrolase family 5 (GH5). BMC Evol Biol 12:186. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-12-186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jun HS, Qi M, Gong J, Egbosimba EE, Forsberg CW. 2007. Outer membrane proteins of Fibrobacter succinogenes with potential roles in adhesion to cellulose and in cellulose digestion. J Bacteriol 189:6806–6815. doi: 10.1128/JB.00560-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kadnikov VV, Mardanov AV, Podosokorskaya OA, Gavrilov SN, Kublanov IV, Beletsky AV, Bonch-Osmolovskaya EA, Ravin NV. 2013. Genomic analysis of Melioribacter roseus, facultatively anaerobic organotrophic bacterium representing a novel deep lineage within Bacteriodetes/Chlorobi group. PLoS One 8:e53047. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frischkorn KR, Stojanovski A, Paranjpye R. 2013. Vibrio parahaemolyticus type IV pili mediate interactions with diatom-derived chitin and point to an unexplored mechanism of environmental persistence. Environ Microbiol 15:1416–1427. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kirn TJ, Jude BA, Taylor RK. 2005. A colonization factor links Vibrio cholerae environmental survival and human infection. Nature 438:863–866. doi: 10.1038/nature04249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clymo RS. 1984. The limits to peat bog growth. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 303:605–654. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1984.0002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Limpens J, Heijmans MMPD, Berendse F. 2006. The nitrogen cycle in boreal peatlands, p 195–230. In Wieder RK, Vitt DH (ed), Boreal peatland ecosystems. Springer, Berlin, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lamers LPM, Bobbink R, Roelofs JGM. 2000. Natural nitrogen filter fails in polluted raised bogs. Glob Chang Biol 6:583–586. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2486.2000.00342.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kravchenko IK. 2002. Methane oxidation in boreal peat soils treated with various nitrogen compounds. Plant Soil 242:157–162. doi: 10.1023/A:1019614613381. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moore T, Blodau C, Turunen J, Roulet N, Richard PJH. 2005. Patterns of nitrogen and sulfur accumulation and retention in ombrotrophic bogs, eastern Canada. Glob Chang Biol 11:356–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2004.00882.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dedysh SN. 2011. Cultivating uncultured bacteria from northern wetlands: knowledge gained and remaining gaps. Front Microbiol 2:184. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boedeker C, Schüler M, Reintjes G, Jeske O, van Teeseling MC, Jogler M, Rast P, Borchert D, Devos DP, Kucklick M, Schaffer M, Kolter R, van Niftrik L, Engelmann S, Amann R, Rohde M, Engelhardt H, Jogler C. 2017. Determining the bacterial cell biology of Planctomycetes. Nat Commun 8:14853. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reintjes G, Arnosti C, Fuchs BM, Amann R. 2017. An alternative polysaccharide uptake mechanism of marine bacteria. ISME J 11:1640–1650. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2017.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, Ma N, Papadopoulos J, Bealer K, Madden TL. 2009. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 10:421. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Staley JT, Fuerst JA, Giovannoni S, Schlesner H. 1992. The order Planctomycetales and the genera Planctomyces, Pirellula, Gemmata, and Isosphaera, p 3710–3731. In Balows A, Tr̈uper HG, Dworkin M, Harder W, Schleifer K-H (ed), The prokaryotes: a handbook on the biology of bacteria: ecophysiology, isolation, identification, applications. Springer, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Neef A, Amann R, Schlesner H, Schleifer KH. 1998. Monitoring a widespread bacterial group: in situ detection of planctomycetes with 16S rRNA-targeted probes. Microbiology 144:3257–3266. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-12-3257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dedysh SN, Derakshani M, Liesack W. 2001. Detection and enumeration of methanotrophs in acidic Sphagnum peat by 16S rRNA fluorescence in situ hybridization, including the use of newly developed oligonucleotide probes for Methylocella palustris. Appl Environ Microbiol 67:4850–4857. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.10.4850-4857.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Milligan B. 1998. Total DNA isolation, p 29–64. In Hoelzel A. (ed), Molecular genetic analysis of populations: a practical approach. IRL Press, Oxford, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Koren S, Walenz BP, Berlin K, Miller JR, Bergman NH, Phillippy AM. 2017. Canu: scalable and accurate long-read assembly via adaptive k-mer weighting and repeat separation. Genome Res 27:722–736. doi: 10.1101/gr.215087.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ye C, Hill CM, Wu S, Ruan J, Ma Z. 2016. DBG2OLC: efficient assembly of large genomes using long erroneous reads of the third generation sequencing technologies. Sci Rep 6:31900. doi: 10.1038/srep31900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brettin T, Davis JJ, Disz T, Edwards RA, Gerdes S, Olsen GJ, Olson R, Overbeek R, Parrello B, Pusch GD, Shukla M, Thomason JA, Stevens R, Vonstein V, Wattam AR, Xia F. 2015. RASTtk: a modular and extensible implementation of the RAST algorithm for building custom annotation pipelines and annotating batches of genomes. Sci Rep 5:8365. doi: 10.1038/srep08365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kanehisa M, Sato Y, Morishima K. 2016. BlastKOALA and GhostKOALA: KEGG tools for functional characterization of genome and metagenome sequences. J Mol Biol 428:726–731. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Medema MH, Blin K, Cimermancic P, De Jager V, Zakrzewski P, Fischbach MA, Weber T, Takano E, Breitling R. 2011. AntiSMASH: rapid identification, annotation and analysis of secondary metabolite biosynthesis gene clusters in bacterial and fungal genome sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 39:W339–W346. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Blin K, Medema MH, Kazempour D, Fischbach MA, Breitling R, Takano E, Weber T. 2013. antiSMASH 2.0—a versatile platform for genome mining of secondary metabolite producers. Nucleic Acids Res 41:W204–W212. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weber T, Blin K, Duddela S, Krug D, Kim HU, Bruccoleri R, Lee SY, Fischbach MA, Müller R, Wohlleben W, Breitling R, Takano E, Medema MH. 2015. antiSMASH 3.0—a comprehensive resource for the genome mining of biosynthetic gene clusters. Nucleic Acids Res 43:W237–W243. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Miller GL. 1959. Use of dinitrosalicylic acid reagent for determination of reducing sugar. Anal Chem 31:426–428. doi: 10.1021/ac60147a030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.