Abstract

Genetically identical organisms grown in homogenous environments differ in quantitative phenotypes. Differences in one such trait, expression of a single biomarker gene, can identify isogenic cells or organisms that later manifest different fates. For example, in isogenic populations of young adult Caenorhabditis elegans, differences in Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) expressed from the hsp-16.2 promoter predict differences in life span. Thus, it is of interest to determine how interindividual differences in biomarker gene expression arise. Prior reports showed that the thermosensory neurons and insulin signaling systems controlled the magnitude of the heat shock response, including absolute expression of hsp-16.2. Here, we tested whether these regulatory signals might also influence variation in hsp-16.2 reporter expression. Genetic experiments showed that the action of AFD thermosensory neurons increases interindividual variation in biomarker expression. Further genetic experimentation showed the insulin signaling system acts to decrease interindividual variation in life-span biomarker expression; in other words, insulin signaling canalizes expression of the hsp-16.2-driven life-span biomarker. Our results show that specific signaling systems regulate not only expression level, but also the amount of interindividual expression variation for a life-span biomarker gene. They raise the possibility that manipulation of these systems might offer means to reduce heterogeneity in the aging process.

Keywords: Nongenetic, Aging, Heat shock

Differences in genes and environments are often used to explain the totality of the variation in any given phenotype. And yet, cell-to-cell and animal-to-animal variation in quantitative phenotypes occurs even when genotype and environment are held constant. Such intrinsic biological variation accounts for the differences in a number of complex quantitative traits, such as mouse body weight, for which the non-genetic, non-environmental component accounts for 70%–80% of the total variation (1). Life span is another quantitative phenotype for which there is a relative abundance of environment- and genotype-independent variation (2). Gene expression, of almost all reporter genes measured in populations of eukaryotic cells and animals, also has significant non-genetic, non-environmental components (3,4). Moreover, variation in expression of single genes correlates with differences in important biological outcomes. For example, murine stem cells, expressing high levels of SCA-1 differentiate into myeloid cells at twice the frequency of cells with low expression (5).

In Caenorhabditis elegans, differences in the amount of Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) expressed under control of the hsp-16.2 promoter after heat shock predict differences in life span, heat tolerance, and health span as measured by locomotion (6–8). Animals with high expression of this Phsp-16.2::gfp life-span biomarker show increased mRNA for multiple chaperones (hsp-17, hsp-70, hsp-16.1, hsp-16.2, hsp-16.41) and exist in a more robust physiological state (6). Recently, we found that several otherwise-isogenic hsp-16.2 promoter reporter strains, differing in reporter insertion site, copy number, 3′UTR, and fluorescent protein, showed identical normalized interindividual variation (identical coefficient of variation, CV) in life-span biomarker expression (4). Our previous investigation found results that were astounding in terms of deviating from the expectations put forth by the power law, which states that even the relative amount of interindividual variation should decrease with increasing expression level. We found that, among the diverse reporters of hsp-16.2 transcription, there was no difference in relative interindividual variation in reporter expression, despite differences in mean of an order of magnitude, replotted in Supplementary Figure S1 to show the reproducibility and trial to trial variation in CV; data also available as raw mean and CV values in Supplementary File F1.

In this study, we reasoned that if this non-genetic, non-environmental variation was not a simple consequence of biochemical noise, it might arise from the action of a program to generate phenotypic diversity. The ideas put forth by Waddington on canalization (9) suggested that there might be genes whose normal function was to canalize, or reduce variation in complex traits, and in fact, mutations that reduce the variation in other quantitative traits (canalizing genes) have been identified (see Discussion). Thus, if there were a biological program to increase variation in quantitative phenotypes (10), it might be possible to identify loss of function mutations that resulted in relatively fewer differences among individuals – mutations defining what one might call diversifying or anticanalizing genes.

Here we sought to identify genes that affected variation (measured by CV) in expression of the Phsp-16.2::gfp life-span biomarker in C elegans. We particularly wanted to identify genes whose normal function might be to increase or anticanalize interindividual variation in gene expression; that is, we sought mutants resulting in fewer differences between individuals in populations of isogenic animals. To do so, we took advantage of the fact that Phsp-16.2 promoter drives expression of a gene encoding a small heat shock protein, and that expression of the Phsp-16.2::gfp biomarker reporter is controlled by the same systems that control the organism’s heat shock response. We reasoned that genetic lesions in the same systems that affected the amount of expression might also affect interindividual variation in the expression of this Phsp-16.2::gfp life-span biomarker.

In C elegans, two systems control the magnitude of the response to heat shock, including the induction of hsp-16.2. The first, the neuronal system, depends on the action of thermosensory neurons (11–15). In terms of effect on thermosensation/thermotaxis, the main thermosensory neurons are the two AFD neurons (11). These cells sense heat (11) and depolarize in response to heat shock (12–15), causing connected neurons (probably the terminal AIY pair (12)) to release some secreted diffusible factor(s) (possibly serotonin (16)). Inside the AFD neurons, as temperature increases, cyclic GMP concentrations increase, presumably through the action of three guanylyl cyclases, GCY-8, GCY-18, and GCY-23 (15). When cyclic GMP concentrations reach some level, they activate the TAX-4 cyclic-nucleotide-gated channel, causing the AFD neurons to depolarize (12–15). Accordingly, both tax-4 and gcy-8 are required for the somatic-heat-shock-response-enhancing depolarization (12). Here we were able to utilize mutants in these genes to test the hypothesis that the thermosensory neuron depolarization in response to thermal stress might increase interindividual variation in life-span biomarker expression. We examined the tax-4(p678) loss of function mutation, which is expressed in ten pairs of sensory neurons (17), including the thermosensory AFD neuron pair. We also examined the gcy8(oy44) loss of function mutation, which is expressed exclusively in the AFDs (15,18), and prevents them from depolarizing in wild-type fashion (14). These two mutants phenocopy one another. In C elegans, the difference between the cellular response with and without depolarization of the AFD neurons operationally defines both the cell-non-autonomous heat shock response and the cell-autonomous remainder (12).

The insulin-like signaling system also affects the magnitude of the cell autonomous heat shock response (19,20), including induction of hsp-16.2 (19,21). In C elegans, insulin signaling requires ligand agonization and antagonization of the insulin-like receptor, the daf-2 gene product (22), which represses or activates, respectively, nuclear translocation of the major downstream transcription factor, the mammalian FOXO3 homolog, the daf-16 gene product (23). When insulin signaling is low (eg, low food or elevated temperatures (24,25)), the DAF-2 receptor decreases intracellular signaling, allowing the DAF-16 transcription factor to translocate to the nucleus (26), and induce expression of a battery of stress response genes, including genes encoding heat shock proteins (19–21,27). Here we used mutants to test the hypothesis that the insulin signaling system might affect interindividual variation in life-span biomarker expression. Specifically, we examined the daf-2(e1370) loss of function mutant, which causes constitutive somatic activation and nuclear translocation of DAF-16 (28). We also examined a mutation with the opposite effect, the daf-16(mu86) null mutant, which disables insulin-like signaling (29).

Experimental details are provided in the Materials and Methods section of Supporting Materials.

Results

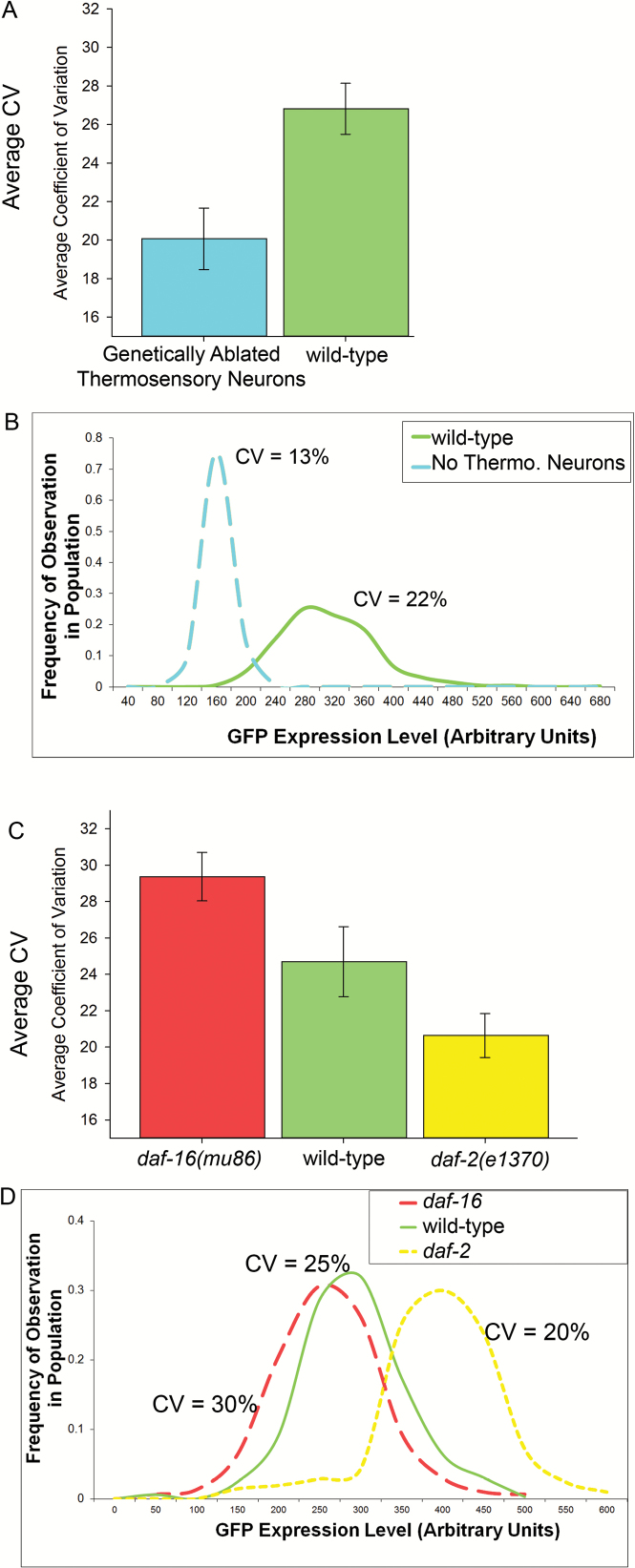

First, as previously reported (12), as assayed by reduced mean Phsp-16.2::gfp expression, we observed a depressed heat shock response when we genetically ablate thermosensory neuron function (Figure 1B, and raw data in (30)) via tax-4(p678) or gcy-8(oy44) mutations, which phenocopy one another. Figure 1A, Supplementary Figure S2, and raw data in (30) show that in comparison with wild-type animals, we also observed consistently less variation in life-span biomarker expression in populations of animals without functional thermosensory neurons. Our results thus suggest that depolarization of the AFD neuron pair increases variation in life-span biomarker gene expression.

Figure 1.

Interindividual variation in expression of Phsp-16.2::gfp in wild-type and mutant animals. (A) Wild-type animals are shown on the right, and the average amount of interindividual variation in Phsp-16.2::gfp expression for thermosensory neuron mutants is shown on the left. Genetic ablation of thermosensory neurons via tax-4 or gcy-8 results in an approximate 20% decrease in interindividual variation; Paired t-test p = .000285, Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test (nonparametric) p = .031. Results are from six independent experiments. (B) An example of a single experiment showing smoothed histograms show expression of Phsp-16.2::gfp in populations of wild-type (solid line) and gcy-8 animals (dashed line) animals. Data is from two populations of about 500 animals each (471 and 511 animals, respectively). Bootstrap analysis of the data for each genotype also found significant differences in CV, shown as 95% confidence intervals in Supplementary Figure S2. Raw data for each of the six experiments (four tax-4, two gcy-8) is available in (30). (C) The average wild-type worm-to-worm variation in Phsp-16.2::gfp expression is shown by the middle bar. The right bar shows the same measures of interindividual variation in gene expression in daf-2(e1370) mutants. The left bar shows data from daf-16(mu86) animals. These mutations resulted in approximately 20% decreases or increases in interindividual variation, respectively; One Way Repeated Measures Analysis of Variance followed by Holm-Sidak method, p < .007 for all comparisons, One Way Repeated Measures Analysis of Variance on Ranks followed by Student-Newman-Keuls Method (nonparametric) p = .028 for daf-2 vs daf-16. Data is for CV from each of three experiments with about 500 animals measured in each group in each experiment. (D) The distributions of three populations of animals from one of the experiments in C are shown. Bootstrap analysis of the data for each genotype found the same significant differences, shown as 95% confidence intervals in Supplementary Figure S2. Raw data for each of the three experiments is available in (30).

We next tested the effects of the insulin-like signaling system on variation in life-span biomarker expression. Again, as assayed by Phsp-16.2::gfp expression, and as expected from previous work (19), we found that disabling the insulin-like signaling via the daf-16(mu86) mutation resulted in a depressed heat shock response, while activating it via the daf-2(e1370) mutation resulted in an increased response (Figure 1D). Disabling the insulin-like signaling system with the daf-16(mu86) mutation resulted in relatively greater inter individual variation in gene expression, whereas activating the insulin-like signaling system via the daf-2(e1370) mutation decreased variation (Figure 1C and D, Supplementary Figure S2 and (30)). Thus, activation of the insulin-like signaling system reduces (canalizes) variation in expression of the life-span biomarker, and, in this biological context, daf-16 is a canalizing gene and daf-2 is a diversifying gene.

Discussion

This work shows that animal-to-animal variation in expression of a life-span biomarker reporter gene can be studied genetically. It also demonstrates that intrinsic operational variation in different heat shock control systems can generate phenotypic variation in the absence of environmental or genetic variation, which can have both consequences for the physiology of individuals and for the fitness of the population (discussed further below). Thus, this report adds to a small number of recent studies identifying genes that can increase (diversify) or reduce (canalize) the amount of variation (eg, CV) in quantitative phenotypes. Below, we discuss pleiotropic effects of the mutations we used to consider how these mutations might be affecting the amount of interindividual variation in life-span biomarker expression. We then consider the degree of interindividual variation in a population as trait that natural selection might select for or against.

In order to compare interindividual variation between two separate populations, we made repeated measures of population CV, pairing control groups with experimental groups in each experiment. In practice, most studies obtain a single instance of population CV from two groups and compare the CVs by bootstrap analyses of the raw population data. However, we had the luxury of performing repeated experiments to determine if we could see reproducible differences in the CV of gene expression for genetically distinct populations. Thus, in addition to bootstrap analyses of our data pooled from many experiments, we were able to use standard statistical tests traditionally used for analyses of percentage values or mean values from populations. Importantly, we reached the same the same statistical conclusions with three different methods of analyses for each dataset (parametric, nonparametric, boostraping).

Pleiotropic Effects of Mutations That Affect Expression of the Phsp-16.2::gfp Life-span Biomarker

Here, we demonstrated an effect on variation in expression of Phsp-16.2::gfp using mutants known to affect the overall heat shock response. In addition to their effects on the expression of this reporter, on heat shock response, and, on life span itself, these particular mutant alleles we used are pleiotropic. Mutations in the daf-2/daf-16 insulin signaling system, including the reference daf-2(e1370) allele, cause non-heat shock related phenotypes as varied as arrest during larval development, adult body shrinkage, gonadal malformation, reduced pharyngeal pumping, and reduced male mating efficiency (25). In addition to their effects on the heat shock response, lesions in gcy-8 and tax-4 have other consequences for the organism, including loss of oxygen sensing, loss of volatile chemical sensing, loss of “social feeding” (31), and loss of carbon dioxide perception (32). It is therefore possible that their effect on variation in life-span biomarker expression are indirect, and not related to their effects on heat shock or life span itself.

The Power Law in Gene Expression Noise and Microbial Cell-to-Cell Versus Animal-to-Animal Variation in Gene Expression

A rich set of theoretical and empirical literature suggests that as gene expression increases, the noise in gene expression falls (33,34). The variance in gene expression that falls with increased expression is called intrinsic noise (3,35), as it is a consequence of promoter bursting and fluctuations in mRNA number. These fluctuations, although important in single celled organisms such as Escherichia coli or budding yeast where much of this work has been performed, and gene expression may be low, are unlikely to be significant in multicellular organisms in cases where gene expression in individual cells is far higher or controlled cell-non-autonomously. Also, even in single celled organisms, not all genes follow the power law (34), and we have shown previously that hsp-16.2 reporters do not ((4) and Supplementary Figure S1). Here we show that multicellular organisms are subject to additional regulation of interindividual variation, and that the degree of variation can be controlled by specific genes.

Genes and Loci That Affect Variation in Quantitative Traits

In this study, we identified individual mutations that increased or decreased variation in the expression of a life-span biomarker in populations of isogenic individuals in homogeneous environments. Here, we discuss previous work that considers circumstances in which variation in quantitative phenotypes might be favored and disfavored (and thus controlled by genes and subject to selection). We also discuss work on genes that affect the amount of variation in quantitative traits.

The researchers who initially considered how differences in quantitative traits might affect fitness were studying variation due to different alleles present in outbred populations, and how the frequency of those alleles might change over time (36,37). But, as we have introduced, not all variation in these traits is due allelic differences. Later research addressed a related issue, variation in quantitative phenotypes within isogenic populations, and how variation might affect population fitness. In this later work (including the work here), variation in phenotype in isogenic populations arises from various mechanisms, and but those mechanisms depend on and are affected by the action of particular genes.

Genes That Decrease Phenotypic Variation

Classically, in stable environments, uniformity in the value of phenotypic traits results in maximum fitness. Restated, in stable environments, an allele, and an organismic genotype, that causes the optimal value of a trait emerges and becomes fixed (38,39). But, given inevitable differences in genotype of organisms within populations, and variation in the environment (at least, over time) how could populations manifest the optimum value of phenotypic traits? In the mid-20th century, Waddington suggested that organisms might have evolved mechanisms by which phenotypic traits manifest uniformly despite differences in environment, genotype, and individual circumstances of embryonic development (9). He called such reduction in interindividual variation “canalization.”

Canalization depends on the action of genes. A well-known example of such a canalizing gene is scute, a basic helix-loop-helix protein, one of the four genes that comprise the achaete-scute complex. scute canalizes bristle number in flies (40). Animals homozygous for a particular mutation, sc, have greater variation in bristle number than wild-type animals (eg, in lines unselected for bristle number, the bristle number of sc flies (sc/Y) falls into four bins, whereas the bristle number of wild-type flies (sc+/Y) falls into three bins). Perhaps best known, is HSP90, which, in Drosophila melanogaster, Arabadopsis thaliana, and Danio rerio normally reduces phenotypic variation that would otherwise exist; partial inhibition of function can increase variation in some traits but not others (41–43). Similarly, in the context of variation in expression of the Phsp-16.2::gfp reporter genes used here, the wild-type daf-16 product (the C elegans FOXO3 homolog) is a canalizing gene: its reduces differences in gene expression among individuals.

Genes That Increase Phenotypic Variation

During the middle 20th century, biologists also began to consider evolutionary circumstances under which variation in phenotypic traits might be favored. In 1953, Levene showed that for species that occupy multiple ecological niches, different phenotypes might be most fit in different niches, resulting in an equilibrium in which multiple phenotypes (and the multiple genotypes assumed to produce them) optimized the fitness of the population (44). Later investigations of reproductive fitness in birds led to the idea that increased variation in a particular quantitative trait, number of eggs laid per reproductive cycle (clutch size), might increase population fitness. The increased fitness arising from multiple clutches was due to the finite risk of catastrophic predation; having five clutches averages two eggs each, with greater variance in clutch size, might be better for an individual’s reproductive fitness than laying one clutch of ten eggs (45). In an accompanying commentary, Slatkin termed concept of increasing reproductive fitness by avoiding catastrophic risk, either by altering the otherwise optimal value of a quantitative trait or by increasing variation in it, “hedging one’s evolutionary bets” (46).

It has been suggested that bet hedging by increased variation applies to many quantitative phenotypes (47) and there is some empirical evidence that it does (10). This idea is also supported by recent theoretical work (48). In this study, Rice found forces pulling phenotypes toward both reduced and increased variation in fitness, with increased efficiency of selection favoring increased variation (48), and, as a consequence, more rapid evolution of the population (48). In C elegans, there is some evidence to support the idea that at least some aspects of variation may be selected for, because, despite the highly canalized development of C elegans (49,50), we know there is a distribution of fitness values, in terms of progeny per worm (51–53) and somatic life span (7,8,54) and stress resistance (6–8). Recently, George Martin has used the term “epigenetic gambling” to describe a particular class of mechanisms that might operate within isogenic populations to exert a diversifying effect on phenotypes including life span, again with the idea that this diversity exerts a similar positive effect on the fitness of the population as a whole (55).

There are examples of genes that act to increase interindividual differences in quantitative traits in isogenic populations. Our prior investigations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae found that a deletion of kss1 resulted in fewer differences among cells in signal sent through the pheromone response system, demonstrating that one function of the wild-type KSS1 gene is to increase variation in pathway output at low pheromone concentration (3). Similarly, studies of variation in phenotype in Arabidopsis thaliana established alleles of the elf-3 gene that increased variation in flowering time (56).

There are also examples of loci (Quantitative Trait Loci) defined by DNA sequence differences that affect the amount of interindividual variation in, for example, gene expression in mice (57) and plant height in maize (58). Interestingly, some of these variation-increasing loci operate only in some environments. For example, some well-defined Quantitative Trait Loci in particular maize strains increase variation in all tested environments including normal cultivation, while others increase variation only in plants grown with reduced water or reduced nitrogen (58,59). Because in maize uniformity of plant height is considered a desirable trait and is under human selection, in this case, we might say that loci that decrease phenotypic uniformity decrease fitness.

Here, we found that, in isogenic populations, the wild-type tax-4 and gcy-8 gene products increased variation in expression of a life-span biomarker. We could call such genes “diversifying” or “anticanalizing,” and, given their possible function in increasing population fitness, we might call them bet hedging genes. However, we note that, ideally to call a gene that increased phenotypic variation in a quantitative trait a bet hedging gene, one would demonstrate that the wild-type allele increased the population’s reproductive fitness in environments that varied over time, and that loss of function in it reduced variation and reduced fitness. Since neither this work, nor the studies of genes and alleles referenced here, examined this issue, we conclude (as others have also noted (10)), evidence that genes that increase variation are “bet hedgers” evolved over the course of selection to increase reproductive fitness remains elusive.

Conclusion

This work establishes, for the first time, that operation of insulin and neuronal signaling systems can affect variation in gene expression. It demonstrates that single genes can act to increase variation in metazoan gene expression, thus, these diversifying/anticanalizing processes can be studied genetically. Identification and understanding of additional diversifying/anticanalizing genes and signaling systems might allow researchers (and one day physicians) to canalize populations of cells, tissues or even animals into more robust, healthier physiological states. Moreover, it suggests that some contribution to the increased phenotypic heterogeneity during aging previously attributed to unspecified stochastic events (55), for example, increased cell-to-cell variation in gene expression observed in old mouse cardiomyocytes (60), might be due to the action of diversifying/anticanalizing genes affecting the operation of particular signaling systems.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data are available at The Journals of Gerontology, Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences online.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging and the National Institute of General Medicine at the National Institutes of Health by grants 4R00AG045341 to A.M. and R01GM97479 to R.B.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

A.M., P.M.T., R.B., and T.E.J. designed experiments. P.M.T. crossed mutations into reporter strains. A.M. performed gene expression measurements. A.M. and M.M.C. analyzed the data. A.M., R.B., and M.M.C. wrote the final draft. A.M. and R.B. wrote initial and final drafts of the paper and guarantee the integrity of the results. We thank George Martin, Daniel Promislow, Bryan Sands, and Angela Mendenhall for thoughtful discussion of and comments on the manuscript. We also wish to thank anonymous reviewers whose comments improved the robustness of the analyses of the gene expression data.

References

- 1. Gärtner K. A third component causing random variability beside environment and genotype. A reason for the limited success of a 30 year long effort to standardize laboratory animals? Lab Anim. 1990;24:71–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kirkwood TB, Finch CE. Ageing: the old worm turns more slowly. Nature. 2002;419:794–795. doi:10.1038/419794a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Colman-Lerner A, Gordon A, Serra E, et al. Regulated cell-to-cell variation in a cell-fate decision system. Nature. 2005;437:699–706. doi:10.1038/nature03998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mendenhall AR, Tedesco PM, Sands B, Johnson TE, Brent R. Single cell quantification of reporter gene expression in live adult Caenorhabditis elegans reveals reproducible cell-specific expression patterns and underlying biological variation. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0124289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chang HH, Hemberg M, Barahona M, Ingber DE, Huang S. Transcriptome-wide noise controls lineage choice in mammalian progenitor cells. Nature. 2008;453:544–547. doi:10.1038/nature06965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cypser JR, Wu D, Park SK, et al. Predicting longevity in C. elegans: fertility, mobility and gene expression. Mech Ageing Dev. 2013;134:291–297. doi:10.1016/j.mad.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rea SL, Wu D, Cypser JR, Vaupel JW, Johnson TE. A stress-sensitive reporter predicts longevity in isogenic populations of Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Genet. 2005;37:894–898. doi:10.1038/ng1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mendenhall AR, Tedesco PM, Taylor LD, Lowe A, Cypser JR, Johnson TE. Expression of a single-copy hsp-16.2 reporter predicts life span. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67:726–733. doi:10.1093/gerona/glr225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Waddington CH. Canalization of development and the inheritance of acquired characters. Nature. 1942;150(3811):563–565. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Simons AM. Modes of response to environmental change and the elusive empirical evidence for bet hedging. Proc Biol Sci. 2011;278:1601–1609. doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.0176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mori I, Ohshima Y. Neural regulation of thermotaxis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1995;376:344–348. doi:10.1038/376344a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Prahlad V, Cornelius T, Morimoto RI. Regulation of the cellular heat shock response in Caenorhabditis elegans by thermosensory neurons. Science. 2008;320:811–814. doi:10.1126/science.1156093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mori I, Ohshima Y. Molecular neurogenetics of chemotaxis and thermotaxis in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Bioessays. 1997;19:1055–1064. doi:10.1002/bies.950191204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wasserman SM, Beverly M, Bell HW, Sengupta P. Regulation of response properties and operating range of the AFD thermosensory neurons by cGMP signaling. Curr Biol. 2011;21:353–362. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2011.01.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Inada H, Ito H, Satterlee J, Sengupta P, Matsumoto K, Mori I. Identification of guanylyl cyclases that function in thermosensory neurons of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2006;172:2239–2252. doi:10.1534/genetics.105.050013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tatum MC, Ooi FK, Chikka MR, et al. Neuronal serotonin release triggers the heat shock response in C. elegans in the absence of temperature increase. Curr Biol. 2014;25:163–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Komatsu H, Mori I, Rhee JS, Akaike N, Ohshima Y. Mutations in a cyclic nucleotide-gated channel lead to abnormal thermosensation and chemosensation in C. elegans. Neuron. 1996;17:707–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yu S, Avery L, Baude E, Garbers DL. Guanylyl cyclase expression in specific sensory neurons: a new family of chemosensory receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:3384–3387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Murphy CT, McCarroll SA, Bargmann CI, et al. Genes that act downstream of DAF-16 to influence the lifespan of Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2003;424(6946):277–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Morley JF, Morimoto RI. Regulation of longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans by heat shock factor and molecular chaperones. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:657–664. doi:10.1091/mbc.E03-07-0532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Walker GA, Lithgow GJ. Lifespan extension in C. elegans by a molecular chaperone dependent upon insulin-like signals. Aging Cell. 2003;2:131–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kimura KD, Tissenbaum HA, Liu Y, Ruvkun G. daf-2, an insulin receptor-like gene that regulates longevity and diapause in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 1997;277:942–946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ogg S, Paradis S, Gottlieb S, et al. The Fork head transcription factor DAF-16 transduces insulin-like metabolic and longevity signals in C. elegans. Nature. 1997;389:994–999. doi:10.1038/40194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Golden JW, Riddle DL. The Caenorhabditis elegans dauer larva: developmental effects of pheromone, food, and temperature. Dev Biol. 1984;102:368–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gems D, Sutton AJ, Sundermeyer ML, et al. Two pleiotropic classes of daf-2 mutation affect larval arrest, adult behavior, reproduction and longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1998;150:129–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Henderson ST, Johnson TE. daf-16 integrates developmental and environmental inputs to mediate aging in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1975–1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hsu AL, Murphy CT, Kenyon C. Regulation of aging and age-related disease by DAF-16 and heat-shock factor. Science. 2003;300:1142–1145. doi:10.1126/science.1083701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Johnson TE, de Castro E, Hegi de Castro S, Cypser J, Henderson S, Tedesco P. Relationship between increased longevity and stress resistance as assessed through gerontogene mutations in Caenorhabditis elegans. Exp Gerontol. 2001;36:1609–1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lin K, Dorman JB, Rodan A, Kenyon C. daf-16: An HNF-3/forkhead family member that can function to double the life-span of Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 1997;278:1319–1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mendenhall AR, Crane MC, Tedesco PM, Johnson TE, Brent R. Data from: C. elegans genes affecting interindividual variation in lifespan biomarker gene expression. Dryad Digital Repository. 2016. doi:10.5061/dryad.m55h6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gray JM, Karow DS, Lu H, et al. Oxygen sensation and social feeding mediated by a C. elegans guanylate cyclase homologue. Nature. 2004;430:317–322. doi:10.1038/nature02714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bretscher AJ, Kodama-Namba E, Busch KE, et al. Temperature, oxygen, and salt-sensing neurons in C. elegans are carbon dioxide sensors that control avoidance behavior. Neuron. 2011;69:1099–1113. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2011.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bar-Even A, Paulsson J, Maheshri N, et al. Noise in protein expression scales with natural protein abundance. Nat Genet. 2006;38:636–643. doi:10.1038/ng1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Newman JR, Ghaemmaghami S, Ihmels J, et al. Single-cell proteomic analysis of S. cerevisiae reveals the architecture of biological noise. Nature. 2006;441:840–846. doi:10.1038/nature04785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Elowitz MB, Levine AJ, Siggia ED, Swain PS. Stochastic gene expression in a single cell. Science. 2002;297:1183–1186. doi:10.1126/science.1070919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Stern C. The Hardy-Weinberg Law. Science. 1943;97:137–138. doi:10.1126/science.97.2510.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hardy GH. Mendelian proportions in a mixed population. Science. 1908;28:49–50. doi:10.1126/science.28.706.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fisher RA. On the dominance ratio. Proc Royal Soc Edinburgh. 1922;42:321–341. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wright S. Evolution in Mendelian Populations. Genetics. 1931;16:97–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rendel JM, Sheldon BL, Finlay DE. Canalisation of development of scutellar bristles in Drosophila by control of the scute locus. Genetics. 1965;52:1137–1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rutherford SL, Lindquist S. Hsp90 as a capacitor for morphological evolution. Nature. 1998;396:336–342. doi:10.1038/24550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Queitsch C, Sangster TA, Lindquist S. Hsp90 as a capacitor of phenotypic variation. Nature. 2002;417:618–624. doi:10.1038/nature749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yeyati PL, Bancewicz RM, Maule J, van Heyningen V. Hsp90 selectively modulates phenotype in vertebrate development. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e43. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0030043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Levene H. Genetic equilibrium when more than one ecological niche is available. Am Naturalist. 1953;87(836):331–333. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gillespie JH. Nautural selection for within-generation variance in offspring number. Genetics. 1974;76:601–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Slatkin M. Hedging one’s evolutionary bets. Nature. 1974;250(5469):704–705. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Philippi T, Seger J. Hedging one’s evolutionary bets, revisited. Trends Ecol Evol. 1989;4:41–44. doi:10.1016/0169-5347(89)90138-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rice SH. A stochastic version of the Price equation reveals the interplay of deterministic and stochastic processes in evolution. BMC Evol Biol. 2008;8:262. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-8-262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sulston JE, Horvitz HR. Post-embryonic cell lineages of the nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1977;56:110–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sulston JE, Schierenberg E, White JG, Thomson JN. The embryonic cell lineage of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1983;100:64–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Casanueva MO, Burga A, Lehner B. Fitness trade-offs and environmentally induced mutation buffering in isogenic C. elegans. Science. 2012;335:82–85. doi:10.1126/science.1213491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Mendenhall AR, Wu D, Park SK, et al. Genetic dissection of late-life fertility in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66:842–854. doi:10.1093/gerona/glr089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wu D, Tedesco PM, Phillips PC, Johnson TE. Fertility/longevity trade-offs under limiting-male conditions in mating populations of Caenorhabditis elegans. Exp Gerontol. 2012;47:759–763. doi:10.1016/j.exger.2012.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wu D, Rea SL, Yashin AI, Johnson TE. Visualizing hidden heterogeneity in isogenic populations of C. elegans. Exp Gerontol. 2006;41:261–270. doi:10.1016/j.exger.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Martin GM. Epigenetic gambling and epigenetic drift as an antagonistic pleiotropic mechanism of aging. Aging Cell. 2009;8:761–764. doi:10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Jimenez-Gomez JM, Corwin JA, Maloof JN, Kliebenstein DJ. Genomic analysis of QTLs and genes altering natural variation in stochastic noise. PLoS Genet. 2011;7(9):e1002295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Fraser HB, Schadt EE. The quantitative genetics of phenotypic robustness. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8635. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0008635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Makumburage GB, Stapleton AE. Phenotype uniformity in combined-stress environments has a different genetic architecture than in single-stress treatments. Front Plant Sci. 2011;2:12. doi:10.3389/fpls.2011.00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Landers DA, Stapleton AE. Genetic interactions matter more in less-optimal environments: a Focused Review of “Phenotype uniformity in combined-stress environments has a different genetic architecture than in single-stress treatments” (Makumburage and Stapleton, 2011). Front Plant Sci. 2014;5:384. doi:10.3389/fpls.2014.00384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Bahar R, Hartmann CH, Rodriguez KA, et al. Increased cell-to-cell variation in gene expression in ageing mouse heart. Nature. 2006;441:1011–1014. doi:10.1038/nature04844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.