Abstract

Cervicogenic dizziness is a sensation of disequilibrium caused by abnormal afferent activity from the neck. Its diagnosis and treatment are challenging. In a case of cervicogenic dizziness, we performed diagnostic upper cervical medial branch nerve blocks with near complete symptomatic relief for around 20 hours. Radiofrequency ablation of these nerves resulted in near complete relief for 7 months. Subsequent repeat ablations provided the same relief lasting for 6–10 months. This case suggests that upper cervical medial branch block can serve as a diagnostic test for cervicogenic dizziness, and radiofrequency ablation of these nerves might be an effective treatment.

Cervicogenic dizziness (CD) as defined by Furman and Cass1 is “a nonspecific sensation of altered orientation in space and disequilibrium originating from abnormal afferent activity from the neck.” People with CD usually complain of dizziness worsened by head movements accompanied by neck pain and headache.2 It was first introduced as “cervical vertigo” in 1955 by Ryan and Cope,3 who reported 3 cases of dizziness that they attributed to cervical spondylosis. They hypothesized that CD results from abnormal afferent input to the vestibular nucleus from damaged joint receptors in the upper cervical region.3 Later Gray4 reported that injection of local anesthetic into the posterior cervical muscles relieved dizziness thought to be caused by cervical muscle dysfunction, supporting a cervical origin of dizziness. Today, the diagnosis of CD remains controversial and one of exclusion because of lack of a confirmatory diagnostic test.5,6

Various treatments have been reported to improve CD to some degree. These include manual therapy,6 vestibular rehabilitation,6,7 acupuncture,8 greater occipital nerve block and trigger point injection,9 and surgery.10 This is the first report of successful treatment of CD with radiofrequency ablation (RFA) of upper cervical medial branch nerves.

CASE DESCRIPTION

The patient provided written permission for publication of the report and signed Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act authorization. A 44-year-old man, former professional tennis player, with medical history of hypertension, migraine, and sleep apnea presented to the pain clinic with primary complaint of dizziness with neck movement accompanied by mild neck pain and right occipital headache. He described his dizziness as light-headedness, like going down a roller-coaster accompanied by nausea and vomiting, with any movement involving head turning to the right. He stated if he rode in the elevator then got off, he would feel as if he was still going up or down. During swimming, he was unable to tell which direction was up or down. Because of the dizziness, he was unable to drive, play tennis, or ride an elevator. He also reported some pain in the right hand.

Cardiovascular, neurological, and vestibular workup were unremarkable. Cervical spine magnetic resonance imaging showed “osteophyte impingement of right C5–6 nerve root.” Vestibular rehabilitation, manual therapy, occupational therapy, and acupuncture were of minimal benefit. The dizziness was thought to be of migrainous origin. Migraine and cervical radicular pain were treated with various analgesics, cervical epidural steroid injections, and physical therapy without improvement of the dizziness. The patient then underwent right C5–6 foraminotomy, which improved his symptoms for 2 years after which they worsened again. Repeat cervical spine magnetic resonance imaging showed “moderate right neuroforaminal stenosis at C5–C6 related to uncinate spurring.” The patient was referred to the pain clinic for potential epidural steroid injection.

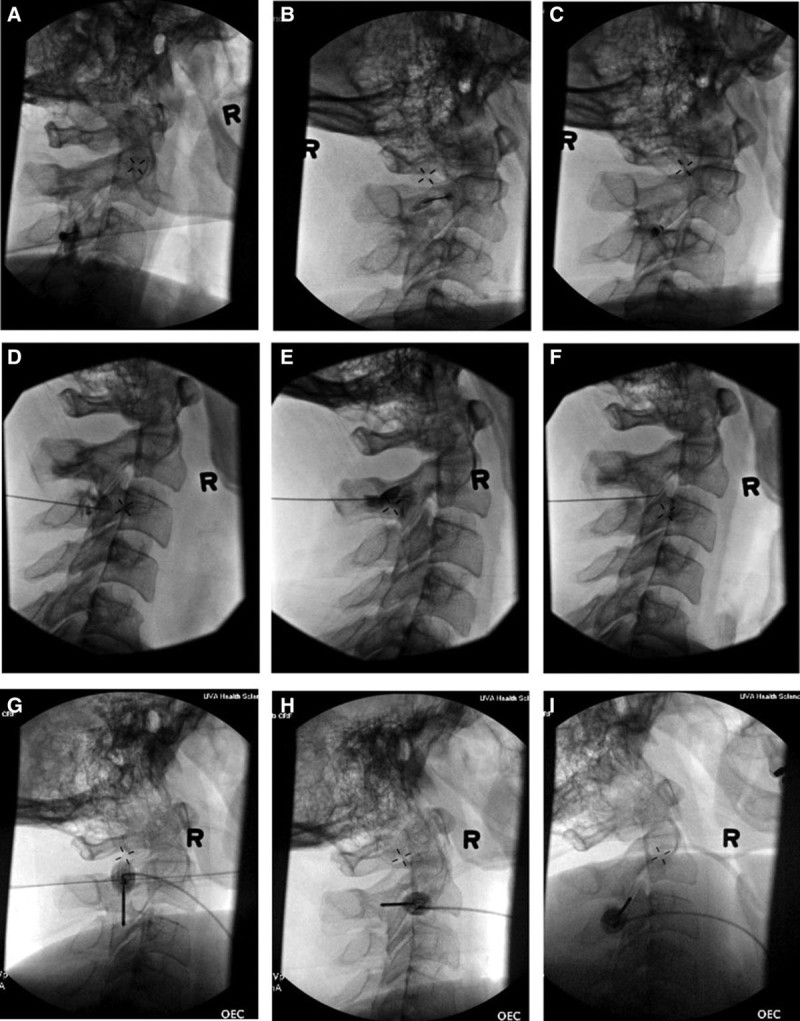

Considering the extensive normal workup, the close relationship between his dizziness and neck movement, the dizziness appeared to be originating from the neck. It reminded us of the rarely seen dizziness in patients after bilateral upper cervical medial branch nerve blocks, which suggests that these nerves are involved in the control of equilibrium. After discussion with the patient, we performed fluoroscopy-guided nerve blocks of the right upper cervical medial branch nerves at C2 and C3, and of the third occipital nerve via lateral approach (Figure, top row) using a 25-gauge, 2-inch needle and injecting 0.5 mL of 0.5% bupivacaine at each level. After the blocks, the patient experienced 18 hours of near complete relief of his dizziness, neck pain, and headache. He had very mild dizziness only when he turned his head to the extreme right. He was able to play tennis, drive, and ride in an elevator. After that, his symptoms returned to baseline. To confirm the results, the same procedure was repeated 3 weeks later. Again, he had almost complete relief of his symptoms for 22 hours.

Figure.

Medial branch nerve block at right C3 (A), C2 (B), and third occipital nerve (C) with a 25-gauge, 2-inch needle, lateral position. Medial branch nerve traditional radiofrequency ablation (RFA) at right C3 (D), C2 (E), and third occipital nerve (F) with a 22-gauge, 3.5-inch needle, prone position. Repeat medial branch nerve cooled RFA at right C3 (G), C2 (H), and third occipital nerve (I) with a 17-gauge, 2-inch needle, lateral position.

Based on the effectiveness of the nerve blocks, and after obtaining informed consent from the patient, 2 weeks later we performed fluoroscopy-guided posterior approach (Figure, middle row) traditional RFA of the C2, C3 medial branch nerves and third occipital nerve using a 22-gauge, 3.5-inch RFA needle with a 5-mm active tip. The dizziness was relieved immediately after the procedure but returned several hours later when the local anesthetic (2% lidocaine) wore off. After 5 days, the dizziness again resolved almost completely. The patient was able to work 4 days per week and perform activities like driving a car and playing tennis without symptoms. He experienced continued relief from the RFA for 7 months. When he then noted a slow return of dizziness, neck pain, and headache over the course of a month, we repeated RFA of the same nerves. So far, he has had a total of 4 RFAs with the same relief, lasting from 6 to 10 months. During the repeat RFAs, cooled (Figure, bottom row) instead of traditional RFA was used which results in larger lesions, thereby increasing the probability of successful denervation of the targeted regenerated nerves and long-lasting relief of symptoms.

DISCUSSION

CD is a controversial diagnosis. There is no consensus regarding its pathophysiology, diagnostic criteria, and optimal treatment.7 Currently, the most prevalent theory is that CD results from abnormal proprioceptive input from upper cervical facet joints and muscles to the vestibular system.5,6,11 Cervical facet joints are the most densely innervated of all the spinal joints,12 and 50% of all cervical proprioceptors were in the joint capsules of C1–C3.13 In addition, there are also mechanoreceptors in the deep segmental upper cervical muscles.14 Animal and human studies suggested that mechanoreceptor input from the uppermost cervical region (occiput to C3) has direct access to the vestibular and visual system, and also converges to the cerebellum, conveying information about the orientation of the head in relation to the rest of the body.2 Given this anatomical and physiological basis, it is understandable that pathology of the upper neck and occipital region can cause dizziness. This reported case supports this theory.

Medial branch nerves are small sensory nerves innervating cervical facet joints. In this case, blocking the upper cervical medial branch nerves with local anesthetic consistently provided near complete relief of the dizziness as well as the neck pain and occipital headache for about 20 hours on 2 separate occasions. The nerve blocks likely disrupted the signal transmission of the abnormal proprioceptive input from the upper cervical facet joints to the vestibular system, and/or other structures controlling balance and orientation. This served a diagnostic purpose indicating the upper cervical facet joints as the origin of the patient’s dizziness and a prognostic purpose suggesting the subsequent RFA of these nerves would very likely provide relief. As expected, the ablation provided long-lasting (7 months) relief appropriate for the kind of procedure, because, after ablation, peripheral nerves will undergo Wallerian degeneration and then regrow over time. When the nerves grow back, symptoms return, needing a repeat ablation. So far, the patient has had 4 ablations with the same relief of his symptoms, lasting from 6 to 10 months.

Altered proprioceptive input from cervical musculature, cervical discs, and occiput may play a role in CD in some patients.6,9,10 Trigger point injection and occipital nerve blocks have been reported to help with CD in some cases,6,9 likely in cases where the dizziness is at least partly caused by muscle, occipital scalp, and/or occipital nerve pathologies. Theoretically, manual therapy and vestibular rehabilitation should help all types of CD provided the altered proprioception mechanism is the main one. Recent studies reported good results from surgical treatment like laser disc decompression.5,10 Unfortunately, there is a lack of literature regarding pharmacological treatment of CD.

The exact incidence of CD is unknown. It has been reported as 20%–58%,6 and as high as 80%–90%8 after whiplash injury. The diagnosis of CD is challenging due to the lack of diagnostic tests and criteria. Vestibular, cardiovascular, and neurological causes should be ruled out before the diagnosis of CD is made. Once CD is diagnosed or suspected, in addition to manual therapy and vestibular rehabilitation, a referral to a pain clinic might be considered to look into its cervical causes. Trigger point injection, occipital nerve block, and upper cervical medial branch nerve block may be helpful in differentiating between cervical musculature, occipital scalp and nerves, and upper cervical facet joints as possible causes of dizziness. If upper cervical medial branch nerve block improves symptoms by at least 75%, RFA might be effective in providing longer-lasting relief. More experimental and clinical studies are warranted to better understand the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment of CD.

DISCLOSURES

Name: Xiaoying Zhu, MD, PhD.

Contribution: This author identified the case in this report and did the majority of the writing of this article.

Name: Michael J. Grover, MD.

Contribution: This author helped with the initial drafting of the manuscript.

This manuscript was handled by: Hans-Joachim Priebe, MD, FRCA, FCAI.

Footnotes

Funding: None.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Furman JM, Cass SP. Balance Disorders: A Case-Study Approach. 1996:Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis Company; 341. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kristjansson E, Treleaven J. Sensorimotor function and dizziness in neck pain: implications for assessment and management. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2009;39:364–377.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ryan GM, Cope S. Cervical vertigo. Lancet. 1955;269:1355–1358.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gray LP. Extra labyrinthine vertigo due to cervical muscle lesions. J Laryngol Otol. 1956;70:352–361.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li Y, Peng B. Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of cervical vertigo. Pain Physician. 2015;18:E583–E595.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wrisley DM, Sparto PJ, Whitney SL, Furman JM. Cervicogenic dizziness: a review of diagnosis and treatment. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2000;30:755–766.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heidenreich KD, Beaudoin K, White JA. Cervicogenic dizziness as a cause of vertigo while swimming: an unusual case report. Am J Otolaryngol. 2008;29:429–431.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heikkilä H, Johansson M, Wenngren BI. Effects of acupuncture, cervical manipulation and NSAID therapy on dizziness and impaired head repositioning of suspected cervical origin: a pilot study. Man Ther. 2000;5:151–157.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baron EP, Cherian N, Tepper SJ. Role of greater occipital nerve blocks and trigger point injections for patients with dizziness and headache. Neurologist. 2011;17:312–317.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ren L, Guo B, Zhang J. Mid-term efficacy of percutaneous laser disc decompression for treatment of cervical vertigo. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2014;24suppl 1S153–S158.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hain TC. Cervicogenic causes of vertigo. Curr Opin Neurol. 2015;28:69–73.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wyke B. Cervical articular contribution to posture and gait: their relation to senile disequilibrium. Age Ageing. 1979;8:251–258.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hülse M. [Differential diagnosis of vertigo in functional cervical vertebrae joint syndromes and vertebrobasilar insufficiency]. HNO. 1982;30:440–446.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sterling M, Jull G, Vicenzino B, Kenardy J, Darnell R. Development of motor system dysfunction following whiplash injury. Pain. 2003;103:65–73.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]