Abstract

Postintubation subglottic stenosis is one of the most common causes of stridor in newborns and babies after prolonged mechanical ventilation. Management of this pathology is complex and requires highly trained personnel because it is associated with a high rate of airway-related mortality. This article presents the rescue of a difficult airway in a pediatric patient with subglottic stenosis with a new device available on the market, the Ventrain, offering certain advantages over those available until now.

This article presents the rescue of a difficult airway in a pediatric patient with subglottic stenosis with the relatively new ventilation device, the Ventrain (Ventinova Medical B.V., Eindhoven, the Netherlands). When the patient desaturated, the device enabled immediate ventilation during airway assessment through a rigid bronchoscope and restoration of normal oxygen saturation. Then, after intubation, ventilation with the Ventrain was valuable again, when conventional mechanical pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) ventilation was very difficult due to elevated pressures. This case clearly indicates that the new ventilation device Ventrain offers advantages over devices available until now.

Parents’ written consent for publication of this case was obtained.

CASE STUDY

We report the case of a 7-month-old, 3700-g girl, with 48 hours of respiratory distress. She was born prematurely at 25 weeks gestation and required prolonged tracheal intubation as a neonate.

Physical examination was positive for wheezing, aphony, and tachypnea, without fever or significant catarrhal symptoms. Prominent wheezing was heard on both hemithoraces, and nebulization with salbutamol was administered. Arterial blood gas analyses showed pH 7.21, Pao2 59 mm Hg, and Paco2 57.5 mm Hg. Subsequently, clinical deterioration occurred with sudden desaturation that required high levels of oxygen and nebulized epinephrine. The patient was admitted to the PICU. Clinical symptoms recurred multiple times. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy revealed 2 subglottic cysts. After uneventful tracheal intubation, 2 posterior subglottic cysts were observed occluding 50% of the subglottic airway. After resection of both cysts with laryngeal microsurgery, steroids were topically administered. After an uneventful extubation, she was transferred to PICU.

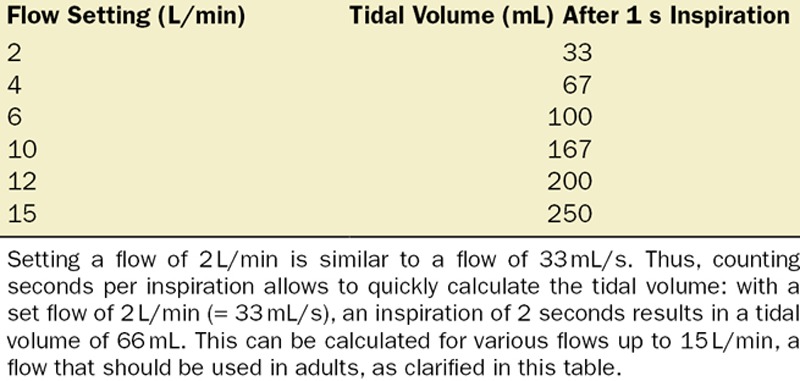

Twenty-four hours later, the patient gradually deteriorated with oxygen desaturation and acute respiratory failure despite noninvasive ventilation. Rigid bronchoscopy revealed significant glotto-subglottic edema. Effective ventilation was achieved through the working channel of the rigid bronchoscope using the manually operated ventilation device, the Ventrain. It provided inspiratory oxygen flow and also enhanced carbon dioxide (CO2) removal by suction (active expiration). Oxygen saturation was rapidly restored. Subsequently, the patient was intubated with an endotracheal tube size 2 with difficulty. To cover the possibility of an emergency surgical intervention on the airway, an ear, nose, and throat specialist was present. After endotracheal intubation, the PICU ventilator was connected in synchronized intermittent mechanical ventilation mode: initial settings rate 35/min, tidal volume 25 mL, inspiration:expiration ratio 1:2, and positive expiratory pressure 4 cm H2O. The high peak pressure of above 50 cm H2O limited adequate chest rise and resulted in progressive CO2 accumulation (above 120 mm Hg). Even after changing several parameters (ratio inspiration:expiration to 1:1), ventilation remained very difficult due to elevated airway pressures. Saturation measured by pulse oximetry decreased to Spo2 85%, requiring ventilation with the Ventrain once again. With a flow of 2 L/min to reach tidal volumes of 33 mL, adequate ventilation was achieved as evidenced by improved pulse oximetry and adequate chest rise. The Ventrain device was connected to a high-pressure oxygen source with a flow regulator using a Mapleson universal connector (Intersurgical, Wokingham, UK). Overall, the baby was manually ventilated with the Ventrain for 5 minutes. After sedation and antiedema measures with steroid therapy, patient’s breathing gradually improved. The baby was then reconnected to the mechanical PICU ventilator. Steroids were administered topically around the tube and intravenously 24 hours before extubation and continued for 48 hours afterward. The patient improved and fully recovered.

DISCUSSION

Laryngeal stenosis is one of the most frequent causes of airway obstruction in children and one of the most common indications of tracheotomy in children under 1 year of age. Although it can have a congenital etiology, 90% of these cases are acquired.1 Acquired stridor is observed in newborns and small infants who have received prolonged mechanical ventilation via tracheal intubation and has an incidence of 0.9%–3% after extubation.2 In the current case, 2 subglottic cysts caused respiratory distress in a 7-month-old baby. Both cysts were removed in 1 surgery. Despite steroid treatment, the described complication occurred. After evaluation of this case, it was concluded that bilateral and contralateral subglottic multiple cysts should not be removed in the same surgery because this might increase the risk of postsurgical upper airway obstruction. However, in this case, the patient was rescued by immediate reoxygenation using the Ventrain, which allowed oxygenation and elimination of CO2 and adequate chest rise and fall through a lumen <2 mm.

Management of severe subglottic stenosis in children is complex and often requires smaller endotracheal tubes than usually used in pediatric ventilation. At our hospital, a committee has been set up to deal with pediatric airways, consisting of a multidisciplinary team including anesthesiologists, surgeons, pulmonologists, radiologists, pediatricians, and ear, nose, and throat specialists, who are responsible for dealing with this kind of pathology. These experts added jet ventilation devices and the Ventrain to our local protocols, ensuring their availability in an emergency airway scenario.

Ventrain has been designed to ventilate through a small lumen tube in patients with difficult airways, when ventilation with a mask or tracheal tube is not possible.3 In in vivo studies, the Ventrain was shown to rapidly reoxygenate desaturated pigs and sheep with obstructed airways,4–7 which are all animal models for adult patients. While studies on infant animal models are lacking,8 1 report describes the rescue of 2 failed pediatric airways.9 Therefore, the Ventrain belongs to a group of rescue ventilation devices for patients in “cannot intubate, cannot ventilate” situations and in those in whom all other devices mentioned in the Difficult Airway Society algorithm11 have failed: situations in which ventilation through only a small-gauge tube is demanded or preferred.

Several other ventilation devices for ventilation through a small-gauge tube/catheter are available on the market to address “cannot intubate, cannot ventilate” situations. In a successful rescue maneuver, these devices provide temporary oxygenation while a more definitive airway plan is devised. However, the use of these ventilation devices is controversial, especially regarding pediatric patients, because many cases of subcutaneous emphysema and barotrauma with pneumothorax and pneumoperitoneum have been reported. These relate to the compromised passive expiration due to a small-gauge tube/catheter in a totally obstructed airway.12

Through a small-gauge tube, patient oxygenation can be established with the classic jet ventilation devices (eg, Manujet; VBM Medizintechnik GmbH, Sulz am Neckar, Germany),10 which are based on high pressure, or with the Enk Oxygen Flow Modulator (OFM; Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN), which is based on the principle of flow supply. An expiratory phase is not allowed during jet ventilation in cases of airway obstruction, increasing the risk of barotrauma. The OFM allows a passive expiratory phase, but with an inspiration-to-expiration ratio of only 1:4. An absent or compromised expiratory phase not only carries the risk of barotrauma, it also limits minute volume.13

The Ventrain, like OFM, is based on flow supply, but additionally, it provides an active expiration by suctioning, achieving inspiration-to-expiration ratios of 1:1 even in cases of small lumen ventilation in an obstructed airway.3–7 This reduces the risk of barotrauma and truly increases the minute ventilation.

The Ventrain only requires oxygen from a high-pressure gas supply with a pressure-compensated flow regulator. The flow can range from 2 L/min for pediatric patients to 15 L/min for adults. The pressure at the distal catheter tip will be no more than what is required to provide the necessary inspiratory flow.3 The Ventrain is easy to use as explained in the Figure. Inspiration is achieved by closing the safety hole with the index finger and the exhaust hole with the thumb. A tidal volume can be administered suiting the patient’s weight by referring to the Table.

Table.

Use of Ventrain Connected to a High-Pressure Gas Oxygen Source With a Pressure-Compensated Flowmeter Enables Calculation of Tidal Volumes

Figure.

Use of Ventrain explained. A, Inspiration is induced by closing both holes with the index finger and thumb. B, Expiration is induced by closing the hole with the index finger and opening the thumb hole. C, Opening both holes results in an equilibration (nonactive) phase.

Expiration is achieved by opening the exhaust hole with the thumb, resulting in suctioning. This allows the elimination of CO2 with an inspiration-to-expiration ratio of around 1:1 and avoids complications from hypercapnia or inability to exhale, pneumothorax, mass pneumoperitoneum, or emphysema.3–7 The passive expiration phase or equilibration phase, by opening both holes, allows the lung pressure to balance with atmospheric pressure.3

The Ventrain offers different Luer-type connection capabilities (eg, [pediatric] cricothyrotomy cannulas, jet ventilation cannulas, intubation catheters). Usually, at this case’s hospital, an airway exchange catheter (COOK Medical) is used in the first attempt to manage an airway stenosis. In this case, only a tube of size 2 could be inserted.

Additional uses of the Ventrain include upper airway surgery, 1-lung ventilation, and emergency situation ventilation. Furthermore, while none of the other devices mentioned enable capnography monitoring, the Ventrain has a side connector that enables monitoring of Etco2.4

Globally, the Ventrain may be available with different specifications (eg, capnometry functionality is not Food and Drug Administration approved).

In the current case, the Ventrain was used to immediately reoxygenate a desaturated baby with a tracheal stenosis through a rigid bronchoscope. Then, when postintubation mechanical ventilation was extremely difficult due to high pressures, again the Ventrain provided adequate ventilation allowing patient stabilization and recovery. This case therefore underlines Ventrain’s added value in managing challenging ventilation situations.

CONCLUSIONS

We consider that the Ventrain offers features that should be taken into account when dealing with the pediatric airway as it is capable of supplying oxygen during inspiration and achieves correct release of CO2 during expiration, significantly reducing the risk of barotrauma and circulatory shock. Ventrain is very simple and easy to use. However, this manually operated device has no alarming function and is not “fool proof.” Therefore, the user should be aware of what he/she is doing and use the device according to manufacturer’s instructions.14

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank José W. A. van der Hoorn for providing the Figure and for her input during the submission process. She is an employee of Ventinova Medical B.V.

DISCLOSURES

Name: Francisco J. Escribá Alepuz, MD, PhD.

Contribution: This author helped care for the patient and write the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

Name: Javier Alonso García, MD.

Contribution: This author helped care for the patient and write the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest: Javier Alonso García is the trainer in airway management scenario at la Fe hospital Valencia.

Name: J. Vicente Cuchillo Sastriques, MD.

Contribution: This author helped care for the patient

Conflicts of Interest: J. Vicente Cuchillo Sastriques is a member of the airway team in the case report.

Name: Emilio Alcalá, MD.

Contribution: This author helped care for the patient.

Conflicts of Interest: Emilio Alcalá is a member of the airway team in the case report.

Name: Pilar Argente Navarro, MD.

Contribution: This author helped write the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest: Pilar Argente Navarro is the head of anesthesia and critical care department la Fe hospital Valencia.

This manuscript was handled by: Raymond C. Roy, MD.

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: See Disclosures at the end of the article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rodríguez H, Cuestas G, Botto H, Cocciaglia A, Nieto M, Zanetta A. Post-intubation subglottic stenosis in children. Diagnosis, treatment and prevention of moderate and severe stenosis. Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp. 2013;64:339–344.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Monnier P. Acquired post-intubation and tracheostomy-related stenoses. Pediatric Airway Surgery. 2011:Basel, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing AG; 183–198.. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamaekers AE, Borg PA, Enk D. Ventrain: an ejector ventilator for emergency use. Br J Anaesth. 2012;108:1017–1021.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berry M, Tzeng Y, Marsland C. Percutaneous transtracheal ventilation in an obstructed airway model in post-apnoeic sheep. Br J Anaesth. 2014;113:1039–1045.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamaekers AE, van der Beek T, Theunissen M, Enk D. Rescue ventilation through a small-bore transtracheal cannula in severe hypoxic pigs using expiratory ventilation assistance. Anesth Analg. 2015;120:890–894.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paxian M, Preussler NP, Reinz T, Schlueter A, Gottschall R. Transtracheal ventilation with a novel ejector-based device (Ventrain) in open, partly obstructed, or totally closed upper airways in pigs. Br J Anaesth. 2015;115:308–316.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Wolf MW, Gottschall R, Preussler NP, Paxian M, Enk D. Emergency ventilation with the Ventrain(®) through an airway exchange catheter in a porcine model of complete upper airway obstruction. Can J Anesth. 2017;64:37–44.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jagannathan N, Sohn L, Fiadjoe JE. Paediatric difficult airway management: what every anaesthetist should know! Br J Anaesth. 2016;117suppl 1i3–i5.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Willemsen MG, Noppens R, Mulder AL, Enk D. Ventilation with the Ventrain through a small lumen catheter in the failed paediatric airway: two case reports. Br J Anaesth. 2014;112:946–947.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ross-Anderson DJ, Ferguson C, Patel A. Transtracheal jet ventilation in 50 patients with severe airway compromise and stridor. Br J Anaesth. 2011;106:140–144.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frerk C, Mitchell VS, McNarry AF, et al. ; Difficult Airway Society Intubation Guidelines Working Group. Difficult Airway Society 2015 guidelines for management of unanticipated difficult intubation in adults. Br J Anaesth. 2015;115:827–848.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duggan LV, Ballantyne Scott B, Law JA, Morris IR, Murphy MF, Griesdale DE. Transtracheal jet ventilation in the ‘can’t intubate can’t oxygenate’ emergency: a systematic review. Br J Anaesth. 2016;117suppl 1i28–i38.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamaekers AE, Borg PA, Enk D. A bench study of ventilation via two self-assembled jet devices and the Oxygen Flow Modulator in simulated upper airway obstruction. Anaesthesia. 2009;64:1353–1358.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noppens RR. Ventilation through a ‘straw’: the final answer in a totally closed upper airway? Br J Anaesth. 2015;115:168–170.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]