Abstract

Ascorbate protects MauG from self-inactivation that occurs during the autoreduction of the reactive bis-FeIV state of its diheme cofactor. The mechanism of protection does not involve direct reaction with reactive oxygen species in solution. Instead it binds to MauG and mitigates oxidative damage that occurs via internal transfer of electrons from amino acid residues within the protein to the high-valent hemes. The presence of ascorbate does not inhibit the natural catalytic reaction of MauG which catalyzes oxidative posttranslational modifications of a substrate protein that binds to the surface of MauG, and is oxidized by the high-valent hemes via long range electron transfer. Ascorbate was also shown to prolong the activity of a P107V MauG variant that is more prone to inactivation. A previously unknown ascorbate peroxidase activity of MauG was characterized with a kcat of 0.24 s−1 and a Km of 2.2 μM for ascorbate. A putative binding site for ascorbate was inferred from inspection of the crystal structure of MauG and comparison with the structure of soybean ascorbate peroxidase with bound ascorbate. The ascorbate bound to MauG was shown to accelerate the rates of both electron transfers to the hemes and proton transfers to hemes which occur during the multistep autoreduction to the diferric state which is accompanied by oxidative damage. A structural basis for these effects is inferred from the putative ascorbate binding site. This could be a previously unrecognized mechanism by which ascorbate mitigates oxidative damage to heme-dependent enzymes and redox proteins in nature.

Keywords: antioxidant, cytochrome, electron transfer, enzyme kinetics, metalloenzyme, peroxidase, post-translational modification

INTRODUCTION

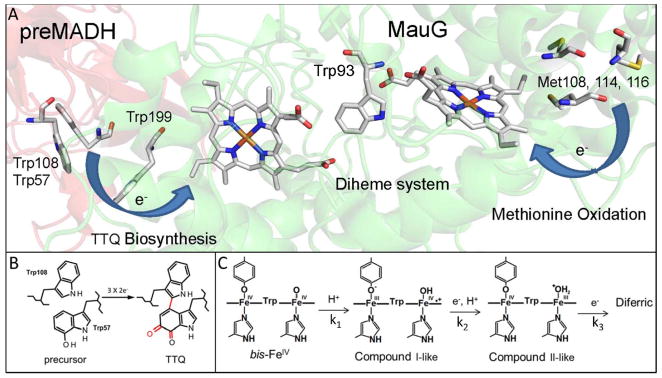

MauG is a diheme enzyme [1] that catalyzes the posttranslational modification a substrate protein [2], a precursor of methylamine dehydrogenase (preMADH) [3]. The residues which are modified are Trp108 and a mono-hydroxylated Trp57 (Figure 1A). These are converted to a protein-derived tryptophan tryptophylquinone (TTQ) cofactor [4]. The reactive intermediate state of MauG is a high-valent bis-FeIV redox state [5] in which the two hemes are each present as FeIV. In this state, a high-spin heme is FeVI=O and a low-spin heme it is FeIV with an oxygen ligand provided by a Tyr side-chain [6, 7]. This redox state is stabilized by a charge resonance transition which is achieved by rapid and reversible electron transfer (ET) through an intervening tryptophan residue (Trp93) [8]. The high-valent state is generated either by addition of H2O2 to the diferric hemes or addition of O2 to the diferrous hemes. The catalytic mechanism requires three two-electron oxidations of the substrate (Figure 1B). These oxidations require long-range hole-hopping mediated ET [9, 10] as preMADH binds to the surface of MauG at point which is distant from the hemes [7]. In the absence of preMADH, the bis-FeIV state undergoes autoreduction to the diferric state [11, 12] (Figure 1C). This results in inactivation of MauG as the source of electrons are specific methionine residues (Met108, 114 and 116) which incur oxidative damage [13, 14].

Figure 1.

Alternative routes for TTQ biosynthesis and oxidative damage in MauG. A. Relevant portion of the structure of the preMADH-MauG complex (PDB entry 3L4M). The hemes of MauG and amino acid residues referred to in the text are displayed in stick. The background of MauG is green and that of preMADH is pink. B. The posttranslational modification that are catalyzed by MauG to achieve TTQ biosynthesis. C. The intermediates in the autoreduction of the bis-FeIV state to the diferric state. The rate constants associated with each reaction step are indicated.

Oxidative stress occurs when the production of free radicals and reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the cell overwhelms the capacity of the cell to neutralize these agents. This causes oxidative damage to proteins, as well as other cell components. Oxidative stress is both a cause and a consequence of many disease states and aging [15–18]. ROS may be produced in healthy cells as a consequence of leakage of electrons from the respiratory chain which react non-specifically [19], and by side-reactions of other oxygen-utilizing enzymes. H2O2 is also a product of the reactions catalyzed by enzymes that are oxidases. ROS in solution can be detoxified by enzymes such as superoxide dismutase and catalase, and by antioxidants such as ascorbate [20]. However, oxidative damage to oxygen-utilizing enzymes may occur internally without involvement of free ROS in solution. Side-reactions involving oxygen can generate radical species on the enzyme which are propagated through the protein and result in oxidative damage to amino acid residues, which inactivates the host enzyme. This phenomenon is poorly understood. MauG provides an opportunity to study such a mechanism. The oxidative damage which inactivates MauG is not the result of reaction with external ROS or radical compounds, but a result of internal ET from amino acids within the protein to the high-valent hemes which generates reactive radical intermediates within the protein which leads to inactivation during the autoreduction of bis-FeIV state in the absence of preMADH [12–14].

Ascorbate is a physiologically important antioxidant which mitigates oxidative stress and the resulting oxidative damage to proteins and other macromolecules in the cell. Ascorbate is known to react directly with ROS in solution. In this study, it is shown that ascorbate protects MauG from self-inactivation on exposure to H2O2 in the absence of the preMADH substrate. It is also shown that ascorbate protects a P107V MauG variant [21] which had previously been shown to be more prone to oxidative damage than the native enzyme [14]. The mechanism by which ascorbate protects MauG does not involve direct reaction with ROS in solution, as it is mitigating oxidative damage that occurs via internal ET within the protein. This process is described and a mechanism is proposed for the interaction of ascorbate with MauG that accounts for these observations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protein purification

Homologous expression of wild-type (WT) MauG [1] and P107V MauG [21] in P. denitrificans, and the methods for the isolation and purification of the proteins were as described previously. Expression of preMADH in Rhodobacter sphaeroides and its purification were as described previously [3, 22].

Spectroscopic and kinetic studies

Formation of bis-FeIV MauG was achieved by addition of stoichiometric H2O2 to the diferric protein [5]. Studies on the autoreduction of bis-FeIV MauG were performed in 10 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.5, at 20 °C. The reactions were monitored spectroscopically using a HP8452A diode array spectrophotometer run by the OLIS SpectralWorks/GlobalWorks software. In order to determine rate constants for the reaction steps and generate the kinetic plots, spectra were globally fit to the changes in absorbance at each wavelength with time. Data analysis was performed with the OLIS software as previously described [11, 23].

Steady-state kinetic studies of reactions of MauG catalyzed TTQ biosynthesis were performed as described previously [24] in 10 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.5, at 25 °C with 0.5 μM WT or P107V MauG. The reactions were initiated by the addition of 5 μM preMADH and 100 μM H2O2. Product formation was monitored by the increase in absorbance centered at 440 nm, which is characteristic of the fully oxidized TTQ in the mature MADH.

Steady-state kinetic studies of reactions of ascorbate peroxidase activity of MauG were performed in 10 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.5, at 25 °C with 0.1 μM WT MauG and varying concentrations of ascorbate. The reactions were initiated by the addition of 100 μM H2O2. The rate of consumption of the ascorbate substrate was monitored by either the decrease in absorbance at 290 nm (ε290 = 2.8 mM−1cm−1) [25, 26] or at 266 nm (ε266 = 13.4 mM−1cm−1). Data were fit by Eq 1, where ν is the initial rate of the reaction. Controls were performed with no MauG present to account for any direct reaction of H2O2 with ascorbate. Under these conditions the rate in the absence of MauG was 0.02 s−1 in the presence of 10 μM ascorbate. This background was subtracted in order to obtain exact rates of the MauG-dependent reaction.

| [1] |

RESULTS

Effects of ascorbate on the rates and kinetic mechanism of the autoreduction of the bis-FeIV state

Oxidation of the diferric state to the bis-FeIV state is accompanied by changes in the Soret region of the absorbance spectrum of MauG [5]. One observes a decrease in intensity and shift of the Soret peak from 406 nm to 408 nm. After reaction with the preMADH substrate the spectrum returns to that of the diferric state [27]. It was previously shown that in the absence of preMADH, a relatively slow autoreduction of bis-FeIV MauG occurs. This is a three-step process (Figure 1C) involving multiple electron and proton transfers [11, 12]. (i) A proton transfer (PT) from solvent generates a Compound I-like state. (ii) A second PT from solvent that is accompanied by a one-electron reduction generates a Compound II-like state. (iii) A second one-electron reduction with loss of water yields the diferric state. The spectral changes associated with each step and the kinetics of the overall reaction were characterized [12].

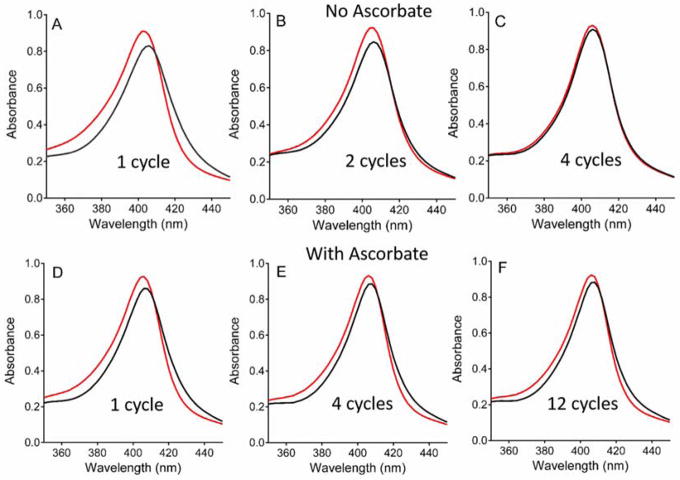

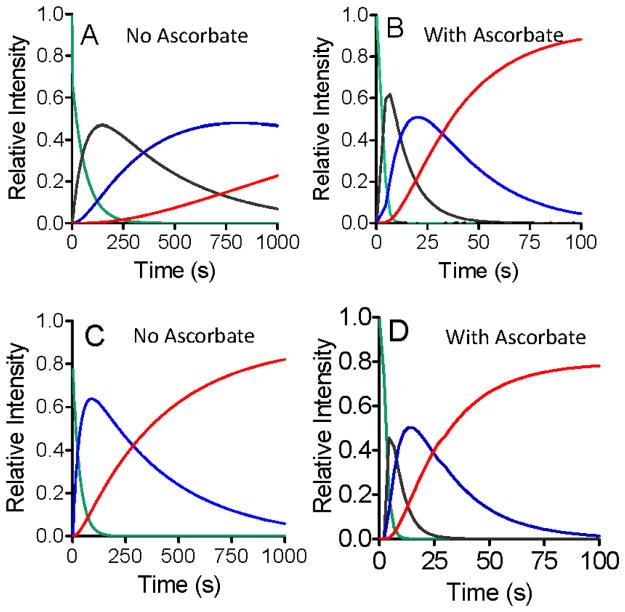

In the absence of preMADH, exposure of MauG to repeated cycles of formation of bis-FeIV and autoreduction leads to permanent changes in the Soret region of the absorbance spectrum of MauG. Complete reactivity of the hemes towards H2O2 is lost after as few as four redox cycles (Figure 2A–C). When this process was repeated in the presence of ascorbate, near normal reactivity is observed even after 12 cycles, with return to the spectrum of the diferric state (Figure 2D–F). Kinetic plots which depict the global fits of the overall changes in the entire spectra with time illustrate the rates of formation and decay of each intermediate state (Figure 3AB). Comparison of the kinetic plots in the absence and presence of ascorbate reveals that the reactions with and without ascorbate proceed through the same intermediate species, but with accelerated rates when ascorbate is present (Table 1). For the reaction of MauG in the absence of ascorbate, the data for the initial autoreduction are best fit by a three-exponential process with rate constants k1= (6.0±0.1) ×10−3 s−1, k2= (5.0±0.01) ×10−3 s−1 and k3= (1.5±0.2) ×10−4 s−1. For the initial reduction of MauG in the presence of ascorbate, the data are again best fit by a three-exponential process with rate constants of k1= 1.38±0.5 s−1, k2= (8.8±0. 3) ×10−2 s−1 and k3= (1.2±0.4) ×10−2 s−1.

Figure 2.

Changes in the Soret region of the absorption spectrum of WT MauG after redox cycling with H2O2 in the absence of preMADH. The spectra are of MauG before (red) and immediately after addition of stoichiometric H2O2 (black) in the absence of preMADH. Spectral changes in the absence of ascorbate were recorded after one (A), two (B) and four (C) cycles. Spectral changes in the presence of ascorbate were recorded after one (D), four (E) and twelve (F) cycles.

Table 1.

Effect of ascorbate on the rate constants for the autoreduction of the bis-FeIV states of WT MauG

| Rate constant | WT MauG | WT MauG + ascorbate | P107V MauG | P107V MauG + ascorbate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| k1 (s−1) | 0.006 ± 0.001 | 1.38 ± 0.05 | Not observed | 0.57 ± 0.04 |

| k2 (s−1) | 0.005 ± 0.001 | 0.088 ± 0.003 | 0.007 ± 0.001 | 0.19 ± 0.04 |

| k3 (s−1) | 0.0015 ± 0.0002 | 0.012 ± 0.004 | 0.0035 ± 0.001 | 0.039 ± 0.004 |

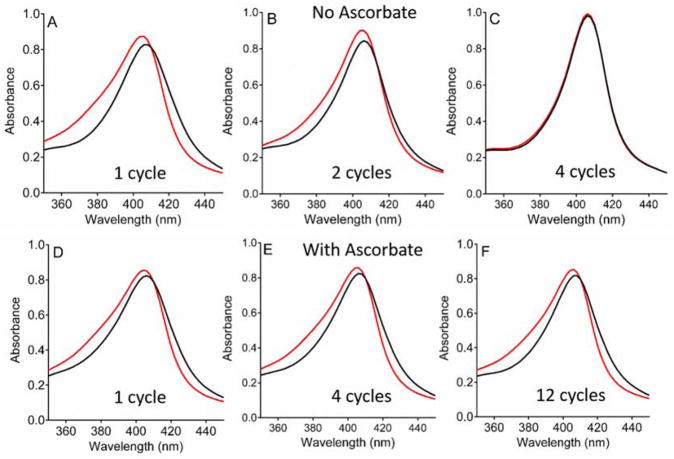

It was previously shown that a P107V MauG variant was more prone to oxidative damage than WT MauG [14, 28]. In contrast to WT MauG, inactivation of P107V MauG occurred when preMADH was present. In other words, MauG was inactivated during the steady-state reaction with preMADH and H2O2. Furthermore, P107V MauG exhibited more extensive oxidative damage after exposure to H2O2 in the absence of preMADH [14]. The spectral features of the Soret region of the spectrum of P107V MauG are slightly altered from that of WT MauG, but very similar changes are observed on the interconversion between the bis-FeIV and diferric states. As with WT MauG, in the absence of preMADH reactivity of the hemes of P107V MauG is completely lost after four redox cycles (Figure 4A–C). Yet even with the higher propensity of P107V MauG towards self-inactivation, in the presence of ascorbate near normal reactivity of the hemes is retained after 12 redox cycles (Figure 4D–F). It was previously reported for P107V MauG that the kinetic plot which depicts the global fits of the overall changes in the entire spectra with time is best fit by a two-exponential process [28]. This is observed again under the conditions used in this study (Figure 3C, Table 1) with rate constants of (7.0 ± 0.1) ×10−3 s−1 and (3.5± 0.01) ×10−3 s−1. For this variant, the bis-FeIV state is directly converted to the Compound II-like state with no kinetically detectable Compound I-like intermediate [28]. When this reaction was analyzed in the presence of ascorbate, the kinetic mechanism was altered to become that of the WT MauG (Figure 3D). The data were now best fit to three-exponential process with rate constants k1= 0.57±0.04 s−1, k2= 0.19±0.04 s−1 and k3= 0.039±0.004 s−1. Thus, in the presence of ascorbate the mechanism of autoreduction of the bis-FeIV state of P107V MauG was now very similar to that of WT MauG in terms of the intermediate states and reaction rates.

Figure 4.

Changes in the Soret region of the absorption spectrum of P107V MauG after redox cycling with H2O2 in the absence of preMADH. The spectra are of P107V MauG before (red) and immediately after addition of stoichiometric H2O2 (black) in the absence of preMADH. Spectral changes in the absence of ascorbate were recorded after one (A), two (B) and four (C) cycles. Spectral changes in the presence of ascorbate were recorded after one (D), four (E) and twelve (F) cycles.

Figure 3.

Kinetic plots that depict the global fits of the overall changes in the absorbance spectrum with time that are associated with the conversion of the bis-FeIV state to the diferric state. Experiments were performed with WT MauG in the absence (A) and presence (B) of ascorbate; and with P107V MauG in the absence (C) and presence (D) of ascorbate. These traces correspond to the disappearance of the starting spectrum of the bis-FeIV state (green), the formation and decay of the spectrum of the Compound I-like state when observable (black), the formation and decay of the spectrum of the Compound II-like state (blue) and the formation of the spectrum of the diferric state (red). Spectra were recorded every 2 s.

Effect of ascorbate on the enzymatic activity of WT MauG and P107V MauG

It was previously reported that redox cycling of MauG between the bis-FeIV and diferric state in the absence of preMADH led to loss of enzymatic TTQ biosynthesis activity [13]. As long as substrate was present, there was no inactivation of the enzyme during the steady-state assay. Reduction of the bis-FeIV state by ascorbate is an energetically very favorable reaction. This raises the question of whether the results described above are simply a consequence of ascorbate reacting directly with the ferryl heme and rapidly reducing it, thus preventing oxidative damage. However, if this were the case, then one would expect the ascorbate to compete with substrate and inhibit the TTQ biosynthesis activity. This is because the rate of ET from preMADH, which is bound at the protein surface, to the FeIV hemes is a relatively slow 0.8 s−1 [27]. To investigate this possibility, the catalytic steady-state reaction was compared in the absence and presence of excess ascorbate. In this experiment, the reaction was initiated by the addition of the H2O2 and preMADH and then allowed to go to completion. Then a subsequent reaction was initiated by another addition the substrates and allowed to go to completion. This was then repeated for a third reaction cycle. The presence of ascorbate had no significant effect on either the initial rate of the steady-state reaction (Table 2) or the extent to which the reaction went to completion. Thus, the ascorbate is not directly or rapidly reducing the bis-FeIV state, which would interfere with the reaction by competing with preMADH as the electron donor.

Table 2.

Effect of ascorbate on the steady-state kcat for multiple cycles of reaction of WT MauG and P107V MauG with its natural substrate

| kcat | WT MauG | WT MauG + ascorbate | P107V MauG | P107V MauG + ascorbate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st reaction (s−1) | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.08 ± 0.01 |

| 2nd reaction (s−1) | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.06 ± 0.01 |

| 3rd reaction (s−1) | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.03 ± 0.01 |

P107V MauG was previously shown to undergo loss of catalytic activity during the steady-state reaction. To determine whether ascorbate could protect this variant from this inactivation even in the presence of preMADH, the same experiment was performed with P107V MauG. In the absence of ascorbate, after the first steady-state reaction cycle subsequent additions of substrate do not yield further significant activity indicating that the enzyme had become completely inactivated. In the presence of ascorbate, activity was observed after the second and third addition of substrate. While the activity of P107V MauG was diminished, it was not abolished as was seen in the absence of ascorbate (Table 2). Thus, ascorbate did at least to some extent protect P107V MauG from inactivation during the steady-state reaction. The sum of these results indicate that ascorbate does not interfere with the reaction of MauG with substrate and H2O2, but it does inhibit the self-inactivation reaction which can alternatively occur after reaction with H2O2.

Ascorbate peroxidase activity of MauG

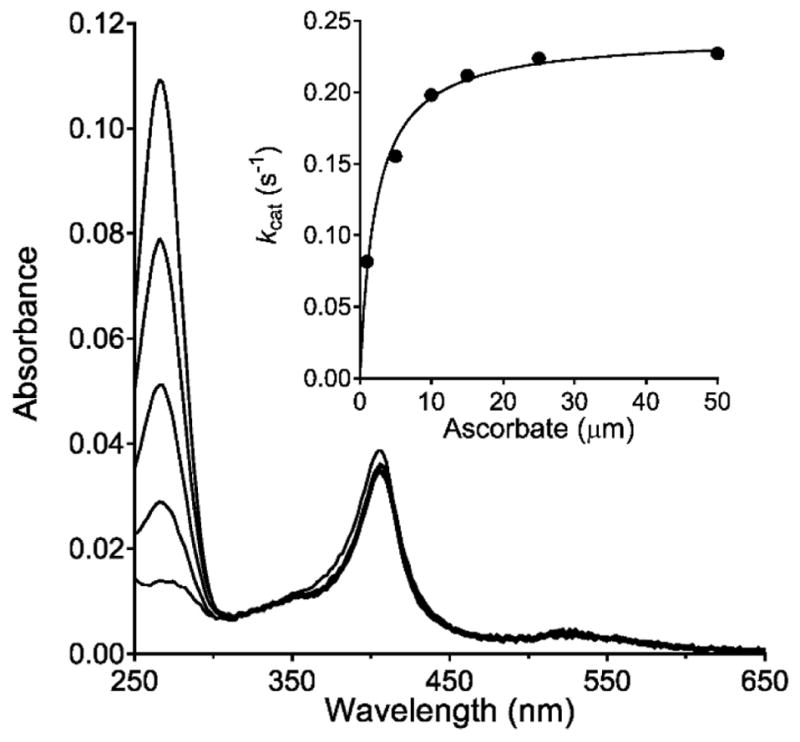

In order to get further insight into the mechanism of its interaction with ascorbate, MauG was assayed for ascorbate peroxidase activity. In the presence of excess H2O2, ascorbate peroxidase activity was observed. Analysis of the dependence of the initial rate of reaction on ascorbate concentration yielded values of kcat = 0.24 ± 0.01 s−1 and Km = 2.2 ± 0.3 μM (Figure 5). The observed saturation behavior for this reaction is consistent with the initial reversible formation of a MauG-ascorbate complex. P107V MauG was also assayed for ascorbate peroxidase activity. It also exhibited a Km of 2.2 μM, and a larger value of kcat of 1.12 ± 0.09 s−1.

Figure 5.

Steady-state analysis of the ascorbate oxidase activity of MauG. The loss of absorbance of ascorbate (centered at 266 nm) in the presence of MauG and H2O2 was used to monitor ascorbate peroxidase activity. The reaction mixture contained 0.1 μM of MauG and 10 μm ascorbate and the reaction was initiated by addition of 100 μm H2O2. Spectra were recorded at 100 s intervals. The peak centered near 400 nm is from the hemes of MauG. The dependence of the initial rate of reaction on ascorbate concentration with varied concentrations of ascorbate is shown in the inset. The curve is the fit of the data by Eq 1.

Effect of hydroxyurea on the rates and kinetic mechanism of the autoreduction of the bis-FeIV state

It was previously reported that the radical scavenger, hydroxyurea [29], afforded partial protection against inactivation of MauG during redox-cycling between bis-FeIV and diferric state in the absence of preMADH [13]. It has also been previously shown that addition of 100 μM hydroxylurea prevented TTQ biosynthesis, however, this was because it reacted with the radical intermediate that was generated on preMADH after reaction with bis-FeIV MauG [5]. As such, the effects of 100 μM hydroxyurea on the kinetics of the autoreduction of bis-FeIV MauG were determined. The effects of hydroxyurea on k2 and k3 were similar to the effects of ascorbate. Those rates increased to 0.13 ± 0.02 s−1 and 0.011 ± 0.02 s−1, respectively. However, whereas ascorbate increased k1 from 0.006 ± 0.01 s−1 to 1.38 ± 0.05 s−1, hydroxyurea increased it only to 0.012 ± 0.02 s−1. Thus, hydroxyurea does not significantly affect the initial proton transfer to the bis-FeIV hemes as did ascorbate. This may be why hydroxyurea only afforded partial protection against inactivation. Furthermore, these results demonstrate that ascorbate is not functioning solely as a radical scavenger.

DISCUSSION

The results indicate that ascorbate binds to MauG and reduces the high-valent hemes in the absence of substrate, but does not interfere with catalysis. This may be explained by the kinetics of the different reactions. The rate of the initial ET from preMADH to the high-valent hemes is 0.8 s−1 [27]. The rate of the initial ET from ascorbate is 0.088 s−1 (k2 in Table 1). The rate of the initial ET the hemes during the autoreduction in the absence of either preMADH or ascorbate is 0.005 s−1 (k2 in Table 1). Thus, the reaction with preMADH is faster than the reaction with ascorbate, which in turn is faster than the reaction with internal Met residues during autoreduction.

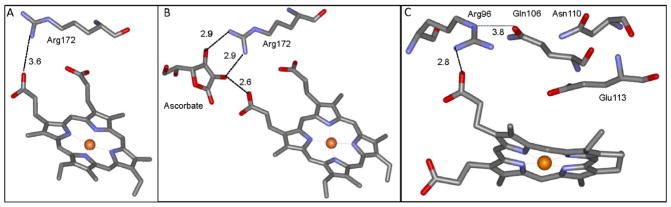

The results of these studies raise the question of where ascorbate is binding since it does not appear to be reacting directly with the ferryl heme in the solvent accessible heme pocket. Insight into this process was gained from comparison of the structure of MauG with that of the well-characterized soybean ascorbate peroxidase (APX) with and without bound ascorbate [30, 31]. The overall structures of the MauG and APX are quite different, and MauG contains two hemes while APX has just one. However, there is some similarity in the region where ascorbate binds to APX with a similar site surrounding the oxygen-binding heme of MauG (Figure 6). In the APX structure with bound ascorbate, it is hydrogen-bonded to a propionate substituent of the heme porphyrin ring and an arginine side-chain in a relatively hydrophilic space (Figure 6B) [30]. In MauG an arginine is present in a similar position in proximity to the propionate of the heme (Figure 6C). The Arg side-chain and heme propionate in MauG, as in APX, reside in a relatively hydrophilic region which is accessible to solvent. This solvent-accessible region is distinct from the solvent-accessible distal pocket of the heme. Thus, ascorbate would have access to this putative binding site in MauG without blocking access to the heme. If ascorbate does bind to this site, then it can donate electrons to the ferryl heme by long-range ET via the propionate to the π-cation radical of the porphyrin of the Compound I-like intermediate (k2) and then to the FeIV of the Compound II-like intermediate (k3). The latter step could involve ET reactions from a bound ascorbate radical formed by the first ET, or another ascorbate which binds after release of the ascorbate radical. ET from the nearby ascorbate would be more efficient that ET from more distant methionine residues which are the source of electrons during the autoreduction. The ET mechanism is also consistent with previous indications that the heme propionate may not simply be an anchor for electrostatic attachment to the protein, but may also play a role in delivering electrons to the heme iron [32].

Figure 6.

Crystal structures of relevant portions of APX and MauG. A. The structure of soybean APX (PDB entry 1OAG). B. The structure of soybean APX in complex with ascorbate (PDB entry 1OAF). C. The structure of MauG (PDB entry 3L4M). Distances in angstroms are indicated next to the dashed lines. The portions of the structures are display as stick with carbon grey, nitrogen blue, oxygen red, and the heme iron as an orange sphere.

Ascorbate also increases the rate of the PT (k1) which precedes the initial ET and converts the bis-FeIV state to a Compound I-like state. This raises the question of how ascorbate would be affecting a PT reaction, especially if it is not directly reacting with the hemes. It was shown that protons are delivered to the heme-bound oxygen from bulk solvent via a network of ordered waters in the distal pocket of the heme [11]. Two PT pathways are operative, one which involves proton tunneling and one which does not. The proposed binding site for ascorbate discussed above (Figure 6C) provides an explanation for how the interaction of ascorbate with MauG could affect the network of waters and amino acid side-chains in such a way to make the PT more favorable. Arg96 is not only within hydrogen bonding distance of the heme propionate but the NE nitrogen is also in close proximity to the OE1 oxygen of Gln106. Arg96 will likely shift position to some extent on binding of ascorbate, which would be coordinated by it and the propionate. This could then affect the position and electrostatic properties of Gln106. This is significant because Gln106 is the entry point for a proton from bulk solvent into the pathway for delivery to the heme oxygen that was designated the pathway involving proton tunneling [11]. The perturbation of Gln106 could make the entry of the proton into the pathway more efficient, thus enhancing the rate of the PT reaction. The importance of Arg96 in this process is supported by the finding in APX that mutation of the corresponding Arg172 to Asn resulted in loss of nearly all activity towards ascorbate and inability to detect the Compound I reaction intermediate [33]. Furthermore, while the autoreduction of bis-FeIV P107V MauG is biphasic reaction with no Compound I-like intermediate detected, in the presence of ascorbate the reduction is triphasic with a kinetically detectable Compound I-like intermediate (Table 1, Figure 3). For these reasons described above, interaction of ascorbate with Arg96 may compensate for the subtle perturbations in the positions of waters and amino acid side-chains that are caused by the P107V mutation [21, 28] so that in the presence of ascorbate, the process is the same as for WT MauG. The observed APX activity of MauG was unexpected. MauG exhibited steady-state values of kcat=0.24 s−1, Km =2.2 μM and kcat/Km = 1.1 × 105 M−1s−1. For the recombinant soybean APX, reported values are kcat=272 s−1, Km =389 μM and kcat/Km = 6.9 × 105 M−1s−1 [25]. Thus, MauG exhibited a much smaller kcat but also a much lower Km which yields a similar kcat/Km value. Interestingly, the P107V MauG which is more prone to oxidative damage exhibits a kcat/Km = 5.1 × 105 M−1s−1. In light of these comparisons, the APX activity of MauG may be considered significant in terms of catalytic efficiency, and surprising specificity for ascorbate as suggested by the relatively low Km value.

The finding that there is a specific site for ascorbate binding in MauG and that it exhibits APX activity has broad implications. MauG and APX have very different overall structures and physiological roles, and they are isolated from diverse sources. MauG is an inducible enzyme that that is localized in the periplasm of gram negative bacteria and is a component of the methylamine utilization (mau) gene cluster in the host bacteria [34]. Its primary, and likely only function is in TTQ biosynthesis to activate MADH [2]. This report demonstrates that MauG is protected from self-inactivation by ascorbate peroxidase activity, and exhibits a high affinity for ascorbate. The presence of a functional ascorbate binding site, in both MauG and APX, which allows indirect interaction with the heme pocket, suggests that this may be a widespread and unrecognized structural feature of heme-containing peroxidases, and perhaps other heme enzymes that generate a ferryl species during their reaction mechanisms. The presence of an Arg residue in proximity to a heme propionate is not unusual and could potentially serve as an ascorbate binding site in other proteins, if the site is accessible to solvent. It is noteworthy that another heme-dependent enzyme, cytochrome c peroxidase, does not exhibit APX activity but it does have an Arg positioned near the heme propionate. Protein engineering which allowed ascorbate access to this site resulted in the acquisition of APX activity [35]. It has also been shown that hemoglobin exhibits peroxidase activity towards ascorbate [36].

The structural feature shown in Figure 6 likely evolved to stabilize the negatively charged heme propionate and has been retained in many heme proteins. In APX’s this feature was adapted to allow the protein to function as a peroxidase. The results obtained with MauG demonstrate that this structural feature may also be exploited as a defense mechanism against radical damage within a protein. The proposed mechanism by which ascorbate protects MauG against oxidative damage is distinct from previously described mechanisms by which ascorbate protects proteins during oxidative stress. These findings may represent a previously unrecognized mechanism by which ascorbate mitigates oxidative damage to heme-dependent enzymes and redox proteins in nature.

Summary.

A novel mechanism is proposed by which ascorbate interacts with the diheme enzyme MauG and protects it from oxidative damage that occurs as a deleterious side-reaction of the high-valent hemes. This mechanism does not involve direct reaction in solution with reactive oxygen species and may be a previously unrecognized mechanism by which ascorbate mitigates oxidative damage to heme-dependent enzymes and redox proteins in nature.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Yu Tang for providing technical assistance, and Dr. Heather Williamson for helpful discussions and suggestions.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number R37GM41574 (VLD).

ABBREVIATIONS

- APX

ascorbate peroxidase

- ET

electron transfer

- preMADH

a precursor protein of methylamine dehydrogenase

- PT

proton transfer

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- WT

wild-type

Footnotes

Declarations of interest

The authors do not have any conflicting financial interests to declare.

References

- 1.Wang Y, Graichen ME, Liu A, Pearson AR, Wilmot CW, Davidson VL. MauG, a novel diheme protein required for tryptophan tryptophylquinone biogenesis. Biochemistry. 2003;42:7318–7325. doi: 10.1021/bi034243q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davidson VL, Wilmot CM. Posttranslational biosynthesis of the protein-derived cofactor tryptophan tryptophylquinone. Annu Rev Biochem. 2013;82:531–550. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-051110-133601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pearson AR, de la Mora-Rey T, Graichen ME, Wang Y, Jones LH, Marimanikkupam S, Aggar SA, Grimsrud PA, Davidson VL, Wilmot CW. Further insights into quinone cofactor biogenesis: Probing the role of MauG in methylamine dehydrogenase TTQ formation. Biochemistry. 2004;43:5494–5502. doi: 10.1021/bi049863l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davidson VL. Pyrroloquinoline quinone (PQQ) from methanol dehydrogenase and tryptophan tryptophylquinone (TTQ) from methylamine dehydrogenase. Adv Protein Chem. 2001;58:95–140. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(01)58003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li X, Fu R, Lee S, Krebs C, Davidson VL, Liu A. A catalytic di-heme bis-Fe(IV) intermediate, alternative to an Fe(IV)=O porphyrin radical. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:8597–8600. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801643105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jensen LM, Meharenna YT, Davidson VL, Poulos TL, Hedman B, Wilmot CM, Sarangi R. Geometric and electronic structures of the His-Fe(IV)=O and His-Fe(IV)-Tyr hemes of MauG. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2012;17:1241–1255. doi: 10.1007/s00775-012-0939-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jensen LM, Sanishvili R, Davidson VL, Wilmot CM. In crystallo posttranslational modification within a MauG/pre-methylamine dehydrogenase complex. Science. 2010;327:1392–1394. doi: 10.1126/science.1182492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geng J, Davis I, Liu A. Probing bis-Fe(IV) MauG: experimental evidence for the long-range charge-resonance model. Angewandte Chemie. 2015;54:3692–3696. doi: 10.1002/anie.201410247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abu Tarboush N, Jensen LMR, Yukl ET, Geng J, Liu A, Wilmot CM, Davidson VL. Mutagenesis of tryptophan199 suggets that hopping is required for MauG-dependent tryptophan tryptophylquinone biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:16956–16961. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109423108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi M, Shin S, Davidson VL. Characterization of electron tunneling and hole hopping reactions between different forms of MauG and methylamine dehydrogenase within a natural protein complex. Biochemistry. 2012;51:6942–6949. doi: 10.1021/bi300817d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ma Z, Williamson HR, Davidson VL. Roles of multiple-proton transfer pathways and proton-coupled electron transfer in the reactivity of the bis-FeIV state of MauG. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:10896–10901. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1510986112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma Z, Williamson HR, Davidson VL. Mechanism of protein oxidative damage that is coupled to long-range electron transfer to high-valent hemes. Biochem J. 2016 doi: 10.1042/BCJ20160047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shin S, Lee S, Davidson VL. Suicide inactivation of MauG during reaction with O2 or H2O2 in the absence of its natural protein substrate. Biochemistry. 2009;48:10106–10112. doi: 10.1021/bi901284e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yukl ET, Williamson HR, Higgins L, Davidson VL, Wilmot CM. Oxidative damage in MauG: implications for the control of high-valent iron species and radical propagation pathways. Biochemistry. 2013;52:9447–9455. doi: 10.1021/bi401441h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Siti HN, Kamisah Y, Kamsiah J. The role of oxidative stress, antioxidants and vascular inflammation in cardiovascular disease (a review) Vascul Pharmacol. 2015;71:40–56. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang X, Wang W, Li L, Perry G, Lee H-g, Zhu X. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1842:1240–1247. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Francesca Bonomini LFR, Rezzani Rita. Metabolic Syndrome, Aging and Involvement of Oxidative Stress. Aging Dis. 2015;6:109–120. doi: 10.14336/AD.2014.0305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gorrini C, Harris IS, Mak TW. Modulation of oxidative stress as an anticancer strategy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12:931–947. doi: 10.1038/nrd4002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cadenas E, Davies KJA. Mitochondrial free radical generation, oxidative stress, and aging1. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;29:222–230. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00317-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pisoschi AM, Pop A. The role of antioxidants in the chemistry of oxidative stress: A review. Eur J Med Chem. 2015;97:55–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feng M, Jensen LM, Yukl ET, Wei X, Liu A, Wilmot CM, Davidson VL. Proline 107 Is a major determinant in maintaining the structure of the distal pocket and reactivity of the high-spin heme of MauG. Biochemistry. 2012;51:1598–1606. doi: 10.1021/bi201882e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Graichen ME, Jones LH, Sharma BV, van Spanning RJ, Hosler JP, Davidson VL. Heterologous expression of correctly assembled methylamine dehydrogenase in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:4216–4222. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.14.4216-4222.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bishop GR, Brooks HB, Davidson VL. Evidence for a tryptophan tryptophylquinone aminosemiquinone intermediate in the physiologic reaction between methylamine dehydrogenase and amicyanin. Biochemistry. 1996;35:8948–8954. doi: 10.1021/bi960404x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li X, Jones LH, Pearson AR, Wilmot CM, Davidson VL. Mechanistic possibilities in MauG-dependent tryptophan tryptophylquinone biosynthesis. Biochemistry. 2006;45:13276–13283. doi: 10.1021/bi061497d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lad L, Mewies M, Raven EL. Substrate binding and catalytic mechanism in ascorbate peroxidase: evidence for two ascorbate binding sites. Biochemistry. 2002;41:13774–13781. doi: 10.1021/bi0261591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mittler R, Zilinskas BA. Purification and characterization of pea cytosolic ascorbate peroxidase. Plant Physiol. 1991;97:962–968. doi: 10.1104/pp.97.3.962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee S, Shin S, Li X, Davidson V. Kinetic mechanism for the initial steps in MauG-dependent tryptophan tryptophylquinone biosynthesis. Biochemistry. 2009;48:2442–2447. doi: 10.1021/bi802166c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma Z, Williamson HR, Davidson VL. Suicide mutation affecting proton transfers to hgh-valent hemes causes inactivation of MauG during catalysis. Biochemistry. 2016;55:5738–5745. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karlsson M, Sahlin M, Sjoberg BM. Escherichia coli ribonucleotide reductase. Radical susceptibility to hydroxyurea is dependent on the regulatory state of the enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:12622–12626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sharp KH, Mewies M, Moody PC, Raven EL. Crystal structure of the ascorbate peroxidase-ascorbate complex. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:303–307. doi: 10.1038/nsb913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sharp KH, Moody PC, Brown KA, Raven EL. Crystal structure of the ascorbate peroxidase-salicylhydroxamic acid complex. Biochemistry. 2004;43:8644–8651. doi: 10.1021/bi049343q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guallar V, Olsen B. The role of the heme propionates in heme biochemistry. J Inorg Biochem. 2006;100:755–760. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2006.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barrows TP, Poulos TL. Role of electrostatics and salt bridges in stabilizing the compound I radical in ascorbate peroxidase. Biochemistry. 2005;44:14062–14068. doi: 10.1021/bi0507128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chistoserdov AY, Boyd J, Mathews FS, Lidstrom ME. The genetic organization of the mau gene cluster of the facultative autotroph Paracoccus denitrificans. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;184:1181–1189. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)80007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meharenna YT, Oertel P, Bhaskar B, Poulos TL. Engineering ascorbate peroxidase activity into cytochrome c peroxidase. Biochemistry. 2008;47:10324–10332. doi: 10.1021/bi8007565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cooper CE, Silaghi-Dumitrescu R, Rukengwa M, Alayash AI, Buehler PW. Peroxidase activity of hemoglobin towards ascorbate and urate: a synergistic protective strategy against toxicity of Hemoglobin-Based Oxygen Carriers (HBOC) Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1784:1415–1420. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2008.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]