Abstract

Condensin plays crucial roles in chromosome organization and compaction, but the mechanistic basis for its functions remains obscure. We used single-molecule imaging to demonstrate that Saccharomyces cerevisiae condensin is a molecular motor capable of adenosine triphosphate hydrolysis–dependent translocation along double-stranded DNA. Condensin’s translocation activity is rapid and highly processive, with individual complexes traveling an average distance of ≥10 kilobases at a velocity of ~60 base pairs per second. Our results suggest that condensin may take steps comparable in length to its ~50-nanometer coiled-coil subunits, indicative of a translocation mechanism that is distinct from any reported for a DNA motor protein. The finding that condensin is a mechanochemical motor has important implications for understanding the mechanisms of chromosome organization and condensation.

Structural maintenance of chromosomes (SMC) complexes are the major organizers of chromosomes in all living organisms (1, 2). These protein complexes play essential roles in sister chromatid cohesion, chromosome condensation and segregation, DNA replication, DNA damage repair, and gene expression. A distinguishing feature of SMC complexes is their large ring-like configuration, the circumference of which is made up of two SMC coiled-coil subunits and a single kleisin subunit (Fig. 1A) (1–4). The ~50-nm-long antiparallel coiled-coil subunits are connected at one end by a stable dimerization interface, referred to as the hinge domain, and at the other end by globular adenosine triphosphatase (ATPase) domains belonging to the ATP-binding cassette family (5). The ATPase domains are bound by a protein of the kleisin family, along with additional accessory subunits, which vary for different types of SMC complexes (Fig. 1A). The relationship between SMC structures and their functions in chromosome organization is not completely understood (6), but many models envision that the coiled-coil domains allow the complexes to topologically embrace DNA (1–4). Given the general resemblance to myosin and kinesin, some early models postulated that SMC proteins might be mechano-chemical motors (7–10).

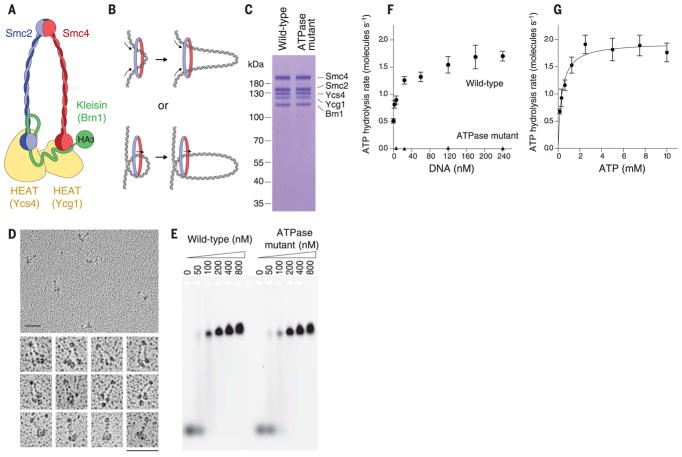

Fig. 1. Biochemistry of budding yeast condensin holocomplexes.

(A) Schematic of the S. cerevisiae condensin complex. The Brn1 kleisin subunit connects the ATPase head domains of the Smc2-Smc4 heterodimer and recruits the HEAT-repeat subunits Ycs4 and Ycg1. The cartoon highlights the position of the HA3 tag used for labeling. (B) Conceptual schematic of loop extrusion for models with either two (top) or one (bottom) DNA strand(s) passing through the center of the SMC ring. (C) Wild-type and ATPase-deficient Smc2(Q147L)-Smc4(Q302L) condensin complexes analyzed by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Coomassie staining (Q, glutamine; L, leucine). (D) Electron micrographs of wild-type condensin holocomplexes rotary-shadowed with platinum/carbon. Scale bars, 100 nm. (E) Electrophoretic mobility shift assays with a 6-carboxyfluorescein–labeled 45-bp dsDNA substrate (100 nM) and the indicated protein concentrations. (F) ATP hydrolysis by wild-type and ATPase mutant condensin complexes (0.5 μM) upon addition of increasing concentrations of a 6.4-kb linear DNA at saturated ATP concentrations (5 mM). The plot shows means ± SD from three (wild-type) or two (ATPase mutant) independent experiments. (G) Michaelis-Menten kinetics for the rate of ATP hydrolysis by wild-type condensin complexes (0.5 μM) at increasing ATP concentrations in the presence of 240 nM 6.4-kb linear DNA. The plot shows means ± SD from three independent experiments. The fit corresponds to a Km of 0.4 ± 0.07 mM for ATP and a kcat of 2.0 ± 0.1 s−1 per molecule of condensin (mean ± SE).

SMC complexes are thought to regulate genome architecture by physically linking distal chromosomal loci, but how these bridging interactions might be established is unknown (1, 2, 11). An early model suggested that many three-dimensional (3D) features of eukaryotic chromosomes might be explained by DNA loop extrusion (Fig. 1B) (12, 13), and recent polymer dynamics simulations have shown that loop extrusion can recapitulate the formation of topologically associating domains, chromatin compaction, and sister chromatid segregation (14–18). This loop extrusion model assumes a central role for SMC complexes in actively creating the DNA loops (11, 12). Similarly, it has been proposed that prokaryotic SMC proteins may structure bacterial chromosomes through an active loop extrusion mechanism (19–21). However, the loop extrusion model remains hypothetical, in large part because the motor activity that is necessary for driving loop extrusion could not be identified (11). The absence of an identifiable motor activity in SMC complexes instead has lent support to alternative models in which DNA loops are not actively extruded but rather are captured and stabilized by stochastic pairwise SMC binding interactions to bridge distal loci (22).

To help distinguish between possible mechanisms of SMC protein–mediated chromosomal organization, we examined the DNA binding properties of condensin (23). We overexpressed the five subunits of the condensin complex in budding yeast and purified the complex to homogeneity (Fig. 1C and fig. S1). Electron microscopy images confirmed that the complexes were monodisperse (Fig. 1D). As previously described for electron micrographs of immunopurified Xenopus laevis or human condensin (24), we observed electron density that presumably corresponds to the two HEAT-repeat subunits in close vicinity to the Smc2-Smc4 ATPase head domains. We confirmed that the Saccharomyces cerevisiae condensin holocomplex binds double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) and hydrolyzes ATP in vitro (Fig. 1, E and F). Addition of dsDNA stimulated the condensin ATPase activity so that it increased about threefold, which is consistent with previous measurements with X. laevis condensin I complexes (25). We found a Michaelis constant (Km) and catalytic rate constant (kcat) of 0.4 ± 0.07 mM and 2.0 ± 0.1 s−1, respectively (means ± SE), for ATP hydrolysis in the presence of linear dsDNA (Fig. 1G). Furthermore, condensin promoted extensive ATP hydrolysis–dependent DNA compaction of single-tethered DNA curtains, which was reversible by increasing the salt concentration to 0.5 M NaCl (fig. S2, A to C). An ATPase-deficient version of condensin with mutations in the γ-phosphate switch loops (Q-loops) of Smc2 and Smc4 still bound DNA (Fig. 1E) but exhibited no ATP hydrolysis activity (Fig. 1F) or DNA compaction activity (fig. S2D).

We then used total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy to visualize binding of single fluorescently tagged condensin holocomplexes to double-tethered DNA substrates (26). We fluorescently labeled condensin with quantum dots (Qdots) conjugated to antibodies against triple copies of the hemagglutinin (HA3) tag fused to the Brn1 kleisin subunit (Fig. 1A). Electrophoretic mobility shift assays confirmed that condensin was quantitatively labeled (fig. S3A). Importantly, binding to the Qdots inhibited neither condensin’s ATP hydrolysis activity nor its ability to alter DNA topology (fig. S3, B and C). We prepared double-tethered curtains by attaching the DNA substrates (~48.5–kb λ-DNA) to a supported lipid bilayer through a biotin-streptavidin linkage; we then aligned one end of the DNA molecules at nanofabricated chromium (Cr) barriers and anchored the other end to Cr pedestals located 12 μm downstream (Fig. 2A) (26).

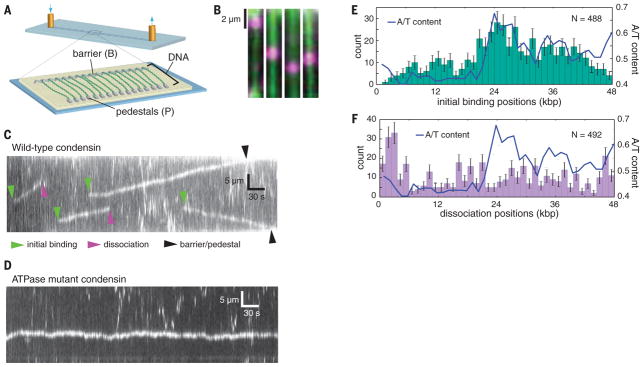

Fig. 2. DNA curtain assay for DNA binding activity of condensin.

(A) Schematic of the double-tethered DNA curtain assay (up and down arrows, inlet and outlet of buffer, respectively). (B) Still images showing Qdot-tagged condensin (magenta) bound to YoYo1-stained DNA (green). (C) Kymograph showing examples of Qdot-tagged condensin translocating on a single DNA molecule (unlabeled); the initial condensin binding sites, dissociation positions, and collisions with the barriers or pedestals are highlighted with color-coded arrowheads. (D) Kymograph showing Qdot-tagged ATPase-deficient mutant Smc2(Q147L)-Smc4(Q302L) condensin undergoing 1D diffusion on DNA (unlabeled). (E) Initial binding site and (F) dissociation site distributions of condensin superimposed on the A/T content of the λ-DNA substrate. All reactions contained 4 mM ATP. Error bars in (E) and (F) represent SD calculated by boot strap analysis. kbp, kilobase pairs.

Using double-tethered curtains, we were able to detect binding of condensin complexes to individual DNA molecules (Fig. 2B). Although we observed single Qdot-tagged condensin complexes, we do not yet know whether the observed complexes were single condensin molecules or condensin oligomers. Kymographs revealed that ~85% of all bound condensin complexes (n = 671) underwent linear motion along the DNA (Fig. 2C and movie S1). The up or down direction of movement was random, but once a complex started to translocate, it generally proceeded unidirectionally without a reversal of direction (reversals were observed occasionally, in 6% of the traces). Condensin has not been previously shown to act as a molecular motor, but the observed movement is fully consistent with expectations for ATP-dependent translocation of a motor protein along DNA. Unlike the wild-type condensin, the ATPase-deficient Q-loop mutant of condensin only exhibited motion consistent with random 1D diffusion (Fig. 2D). Wild-type condensin in the presence of the nonhydrolyzable ATP analog ATPγS also displayed only 1D diffusion (fig. S4A). Previous single-molecule experiments demonstrated rapid 1D diffusion of cohesin on DNA but found no evidence for ATP-dependent translocation, suggesting that there may be differences in how the two SMC complexes process DNA (27, 28).

Analysis of the initial binding positions for wild-type condensin revealed a preferential binding to A/T-rich regions (Pearson’s r = 0.66, P = 5 × 10−6; Fig. 2E), similar to that reported for Schizosaccharomyces pombe cohesin (27). In contrast, the condensin dissociation positions were not correlated with A/T content (Pearson’s r = −0.05, P = 0.77), nor were there any other preferred regions for dissociation within the DNA, with the exception of the Cr barriers and pedestals (Fig. 2F). These findings are consistent with a model where condensin loads at A/T-rich sequences and then translocates away.

We used particle tracking to quantitatively analyze the movement of condensin on DNA (Fig. 3, A and B; fig. S4B; and data S1). Wild-type condensin did not travel in a preferred direction; rather, 52% (255/491) of the complexes went one direction, and 48% (236/491) went the opposite direction. The condensin ATPase mutant did not exhibit any evidence of unidirectional translocation. Mean squared displacement (MSD) plots generated from condensin tracking data exhibited increasing slopes (Fig. 3C), which is only consistent with directed motion (29). In contrast, MSD plots were linear for the ATPase-deficient condensin mutant (Fig. 3D) and for wild-type condensin in the presence of ATPγS (fig. S4C). Linear MSD plots were characteristic of random diffusive motion (29), yielding diffusion coefficients of (1.7 ± 1.4) × 10−3 and (0.8 ± 1.0) × 10−3 μm2 s−1 (means ± SD) for ATPase-deficient condensin and wild-type condensin plus ATPγS, respectively.

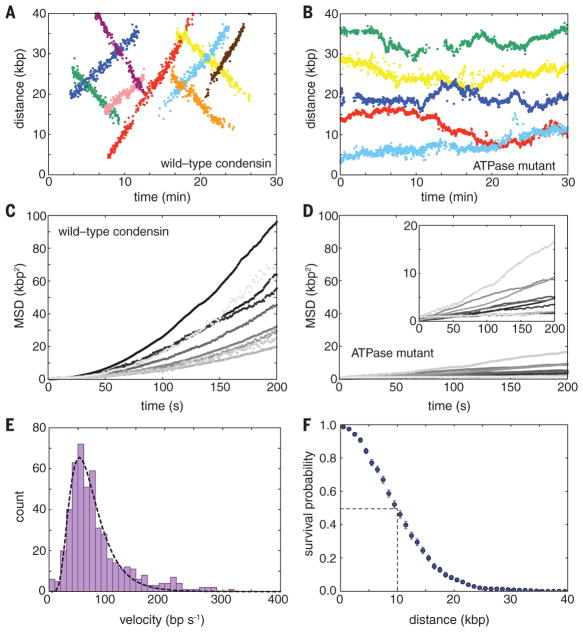

Fig. 3. Condensin is an ATP-dependent mechanochemical molecular motor.

(A) Examples of tracked translocation trajectories for Qdot-tagged wild-type condensin and (B) for the ATPase-deficient Smc2(Q147L)-Smc4(Q302L) condensin mutant. (C) Mean squared displacement (MSD) plots for wild-type condensin and (D) for the ATPase-deficient mutant, obtained from the tracked trajectories. The inset in (D) is a magnification of the main curves. (E) Velocity distributions for condensin translocation activity. The dashed line is a log-normal fit to the translocation rate data. (F) Processivity measurements of condensin motor activity. The dashed line highlights the translocation distance corresponding to dissociation of one half of the bound condensin complexes. Error bars represent SD calculated by boot strap analysis.

We used the tracking data to determine the velocity and processivity of wild-type condensin. A plot of the velocity distributions for data collected in the presence of saturated concentrations of ATP (4 mM; Fig. 1G) was well described by a log-normal distribution, revealing a mean apparent translocation velocity of 63 ± 36 base pairs (bp) s−1 (16 ± 9 nm s−1; means ± SD; n = 491) (Fig. 3E). Upon initial binding, condensin paused for a brief period (τpause = 13.3 ± 1.5 s; mean ± SD) before beginning to move along the DNA, which suggests the existence of a rate-limiting step before condensin becomes active for translocation (Fig. 2C and fig. S5). Each translocating condensin complex remained bound to the DNA for an average total time of 4.7 ± 0.2 min and traveled an average of 10.3±0.4 kb (2.6 ± 0.1 μm; means ± SD) before dissociating (Fig. 3F and fig. S6A). These values provide merely a lower limit of the processivity of condensin, because a considerable fraction (42%) of the complexes traveled all the way to the ends of the 48.5-kb λ-DNA, where they collided with the Cr barriers or pedestals (for example, Fig. 2C). There was no correlation between translocation velocity and processivity at a given ATP concentration (Pearson’s r = 0.035, P = 0.43 at 4 mM ATP) (fig. S6B). However, velocity and processivity both varied with ATP concentrations. From Michaelis-Menten analysis, we found a maximum velocity of 62 ± 2 bp s−1 and a Km of 0.2 ± 0.04 mM ATP (means ± SD) (fig. S7, A and B). The initial pause time (τpause) also varied with ATP concentration, from 3.9 ± 0.8 min at 50 μM ATP to 13.3 ± 1.5 s at 4 mM ATP (means ± SD), suggesting that this delay reflects a transition from a translocation-inactive to a translocation-active state that is dependent on ATP binding, ATP hydrolysis, or both (fig. S7C).

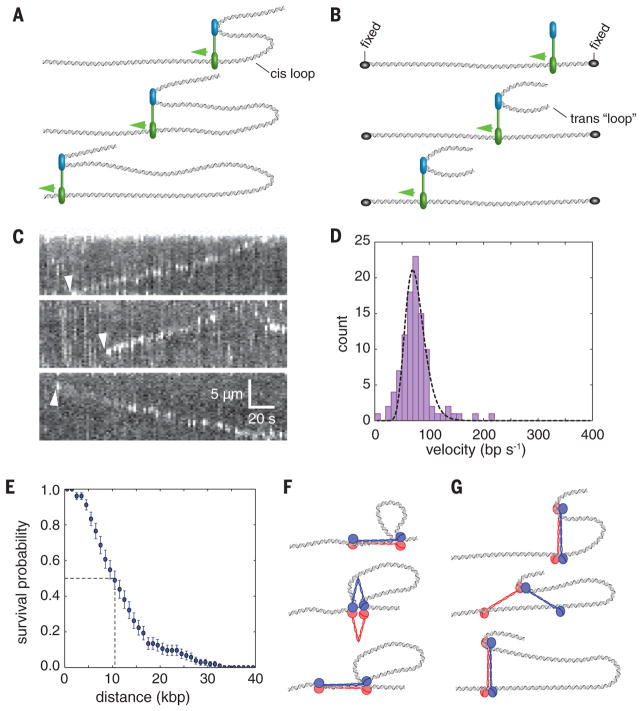

Our finding that condensin is an ATP hydrolysis–dependent molecular motor lends support to models invoking SMC protein–mediated loop extrusion as a means for 3D genome organization. An important prediction of the loop extrusion model is that condensin must simultaneously interact with two distal regions of the same chromosome, and at least one (or possibly both) of the interaction sites must translocate away from the other site, allowing for movement of the two contact points relative to one another (Fig. 4A) (12, 14–17). Such “cis” loop geometry is inaccessible in our double-tethered assays because the DNA is held in an extended configuration (Fig. 2A), which likely decouples loop extrusion from translocation. However, a cis loop configuration can be mimicked experimentally by providing a second DNA molecule in trans (Fig. 4B). To test the possible relationship between the observed linear translocation of condensin along the double-tethered DNA and the loop extrusion model, we asked whether condensin could move a second DNA substrate provided in trans relative to the tethered DNA. Indeed, fluorescently labeled (not extended)λ-DNA molecules added in trans to wild-type condensin moved at an apparent velocity of 76 ± 19 bp s−1 (19±5 nm s−1; n =102)(Fig. 4, C and D; movie S2; and data S2) while traveling an average distance of 11 ± 0.9 kb (2.7 ± 0.2 μm; means ± SD; n = 102) (Fig. 4E)—numbers that match well with the measured condensin motor properties reported above. These experiments strongly indicate that translocating condensin complexes were able to interact simultaneously with the tethered DNA and a second DNA. Also, condensin could translocate while bound to both DNA substrates, given that one piece of DNA was observed to move with respect to the other piece of DNA. Thus, we conclude that condensin is capable of moving two DNA substrates relative to one another, fulfilling a key expectation of the loop extrusion model.

Fig. 4. Coupling condensin motor activity to DNA loop extrusion.

(A) Minimal mechanistic framework necessary for coupling ATP-dependent translocation to the extrusion of a cis DNA loop. In this generic model, a motor domain (green) must move away from another DNA binding domain (blue), and the latter domain can either remain stationary (as depicted) or act as a motor domain and move in the opposite direction (not depicted). (B) Detection of cis loop extrusion is not possible when the DNA is held in a fixed configuration, as in the double-tethered curtain configuration that allows for direct detection of condensin motor activity in the absence of condensation (top). The middle and bottom panels show a schematic of an assay to mimic cis DNA loop extrusion by providing a second λ-DNA substrate in trans. (C) Examples of kymographs showing translocation of a second λ-DNA substrate (stained with YoYo1) provided in trans in the presence of unlabeled condensin. The presence of the trans DNA substrate is revealed as regions of locally high YoYo1 signal intensity, as highlighted by arrowheads. The regions of higher signal intensity are not detected when the trans DNA is omitted from the reaction. (D) Velocity distribution histogram and (E) survival probability plot for condensin bound to the trans DNA substrate. The dashed line in (E) highlights the translocation distance corresponding to dissociation of one half of the bound condensin complexes. Error bars represent SD calculated by boot strap analysis. Cartoons of generalized models for condensin motor activity through (F) “scrunching” or (G) “walking” mechanisms, both of which can be based on ATP hydrolysis–dependent changes in the geometry of the SMC coiled-coil domains.

Heretofore, a common argument against SMC proteins acting as molecular motors was their low rates of ATP hydrolysis relative to other known nucleic acid motor proteins, which implied that they would not move fast enough to function as efficient motors on biologically relevant time scales. However, this discrepancy can be readily reconciled if condensin is able to take large steps, which is conceptually possible given its large size of >50 nm. The available data, in fact, suggest a large step size: Comparison of the single complex translocation rate (~60 bp s−1, or ~14.9 nm s−1) with the bulk rate of ATP hydrolysis (kcat = 2.0 s−1 in the presence of linear DNA) indicates that condensin may take steps on the order of ~30 bp per molecule of ATP hydrolyzed. Even larger steps can be inferred if each step is coupled to the hydrolysis of more than one molecule of ATP. These estimates assume that all of the proteins are ATPase-active (one would deduce a smaller step size if a fraction of the protein were inactive) and also assume perfect coupling between ATP hydrolysis and translocation (whereas a more inefficient coupling would necessitate even larger step sizes). The idea that condensin takes very large steps is consistent with the step sizes reported from magnetic tweezer experiments examining DNA compaction induced by X. laevis condensin [80 ± 40 nm; mean ± SD (30)] or S. cerevisiae condensin (31). Such large step sizes would seem to rule out models of movement for condensin that resemble those for common DNA motor proteins such as helicases, translocases, or polymerases, which are typically found to move in 1-bp increments (32–35). Higher-resolution measurements may prove informative for further defining the fundamental step size of translocating condensin.

To explain our results, we searched for possible models for condensin motor activity that (i) can explain the relationship between a slow ATP hydrolysis rate relative to the rate of translocation, (ii) can accommodate a very large step size, and (iii) are consistent with the physical dimensions of the SMC complex. Given these criteria, we can think of two theoretical possibilities, both of which use the SMC coiled-coil domains as the means of motility. Condensin might translocate along DNA through reiterative extension and retraction of the long Smc2-Smc4 coiled-coil domains, allowing for movement through a “scrunching” mechanism involving rod- to butterfly-like structural transitions (Fig. 4F); alternatively, condensin may use a myosin- or kinesin-like “walking” mechanism (Fig. 4G). The maximum single step size for each model is defined by the physical dimensions of the SMC coiled-coil domains, corresponding to ≲50 and ≲100 nm for the scrunching and walking mechanisms, respectively (Fig. 4, F and G). Both models are consistent with the range of condensin architectures observed by electron and atomic force microscopy (24, 36). Movements might be powered by ATPase-dependent transitions between different structural states similar to those reported for prokaryotic SMC complexes (21, 37, 38), although it remains to be determined how conformational changes could be translated into the directed movement depicted in our models. Further refinement of the translocation mechanism will depend on fully defining the structural transitions that take place during the ATP hydrolysis cycle and establishing a better understanding of whether (and if so, how) different domains in the condensin complex engage DNA.

Recent Hi-C studies have shown that condensin-dependent DNA juxtaposition occurs at an apparent rate of ~900 bp s−1 in Bacillus subtilis (19). This rate is ~15 times as fast as the rates that we observed for single S. cerevisiae condensin complexes. However, the apparent rate of in vivo DNA juxtaposition may reflect the cumulative action of multiple condensin complexes functioning in concert. Assuming that there are ~30 SMC complexes per replication origin, and that the mechanism of DNA juxtaposition allows for a linear relationship between the number of SMC complexes present and the rate of DNA juxtaposition, then each B. subtilis condensin might be expected to translocate along DNA at a rate of ~30 bp s−1. But these comparisons should be made with extreme caution, because at present it is unclear whether the biophysical properties of the molecular machinery of the prokaryotic system are similar to those of the eukaryotic counterpart, and a recent single-molecule analysis of the B. subtilis SMC complex on flow-stretched DNA did not find evidence for translocation on DNA (39).

The finding that S. cerevisiae condensin is a mechanochemical motor capable of translocating along DNA has important implications for understanding fundamental mechanisms of chromosome organization across all domains of life. We propose that the ATP hydrolysis–dependent motor activity of condensin may be intimately linked to its role in promoting chromosome condensation, suggesting that condensin, and perhaps other SMC proteins, may provide the driving forces necessary to support 3D chromosome organization and compaction through a loop extrusion mechanism. Our findings raise the questions of whether other types of SMC complexes also exhibit intrinsic motor activity and what molecular or regulatory features distinguish SMC motor proteins from those SMC complexes that seemingly lack motor activity.

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1. Purification of budding yeast condensin holocomplexes. (A) Size exclusion chromatograms of wild-type and ATPase-deficient Smc2(Q147L)–Smc4(Q302L) condensin complexes. (B) Analysis of peak fractions (grey bar) of the wild-type condensin purification by SDS PAGE and Coomassie staining.

Fig. S2. Condensin can reversibly compact single-tethered DNA curtains. (A) Schematic of the single-tethered DNA curtain assay used to test for DNA compaction by unlabeled condensin. (B) Still images showing the YoYo1-stained DNA before addition of wild-type condensin, after a 20-minute incubation with 10 nM condensin and 4 mM ATP, and still images after chasing the reactions with 500 mM NaCl. Note that the integrated signal intensity of the extended and compacted DNA molecules should not be compared to one another due the change in the location of the DNA with respect to the penetration depth of the evanescent field. (C) Still images showing the YoYo1-stained DNA before addition of wild-type condensin, after a 20-minute incubation with 10 nM condensin and 4 mM ATP S. (D) Still images showing the YoYo1-stained DNA before addition of ATPase deficient condensin, after a 20-minute incubation (in the absence of buffer flow) with 10 nM ATPase-deficient condensin mutant and 4 mM ATP.

Fig. S3. Condensin labeling with quantum dots. (A) Native composite agarose-acrylamide gel electrophoresis of wild-type condensin complexes upon addition of Qdots coupled to antibodies directed against the HA3 epitope tag at the C terminus of the Brn1 kleisin condensin subunit. (B) Effect of increasing ratios of anti-HA Qdot on the ATPase hydrolysis rate by wild-type condensin complexes (0.1 μM) in the presence of 6.4-kb linear DNA (240 nM) at saturated ATP concentrations (5 mM). (C) Nick ligation assay of a 6.4-kb circular DNA (1 nM) with wild-type condensin complexes alone and in the presence of an equimolar amount of anti-HA Qdot.

Fig. S4. Condensin exhibits no motor activity in reactions with ATPγS. (A) Kymograph showing condensin bound to DNA in the presence of 4 mM ATPγS. (B) Examples of particle tracking data, and (C) MSD plots for data collected with wild-type condensin in reactions with 4 mM ATPγS.

Fig. S5. Condensin pauses prior to initiating translocation. (A) Kymograph highlighting the initial pause (τpause) prior to the initiation of translocation (also see Fig. 2C). (B) Histogram showing the distribution of initial pause times prior to initiating translocation for reactions containing 4 mM ATP.

Fig. S6. Condensin’s DNA-binding properties. (A) Distribution of binding lifetimes for translocating condensin complexes. (B) Scatter plot showing that there is no apparent correlation between condensin translocation velocity and processivity. All data shown in this figure reflect results from experiments conducted in the presence of 4 mM ATP.

Fig. S7. ATP concentration dependence of condensin translocation characteristics. (A) Condensin translocation velocity versus ATP concentration for data collected at room temperature (~25°C). The data are fit to the Michaelis-Menton equation to extract the kinetic parameters Km and vmax. (B) Condensin processivity at different ATP concentrations, as indicated. (C) Initial condensin pause times (τpause) prior to initiating translocation at different ATP concentrations. For each graph, error bars represent standard deviations calculated by boot strap analysis.

Data S1. Particle tracking data for condensin translocation. This PDF file presents all of the raw data pertaining to Fig. 3E for condensin translocation on double-tethered DNA curtains. Each of the data panels (491 total) contains a raw kymograph displaying the movement on condensin on the DNA, a corresponding graph of the particle tracking data for the kymograph, and a linear fit to the tracking data. The slope of the linear fit, reflecting the average velocity for the condensin shown in the kymograph, is also shown.

This PDF file presents all of the raw data pertaining to Fig. 4D for condensin translocation on double-tethered DNA curtains while bound to a second DNA in trans. Each of the data panels (102 total) contains a raw kymograph displaying the movement on condensin on the DNA, a corresponding graph of the particle tracking data for the kymograph, and a linear fit to the tracking data. The slope of the linear fit, reflecting the average velocity for the condensin shown in the kymograph, is also shown.

This video shows a typical example of a ~48-kb double-tethered DNA molecule (unlabeled) bound by quantum dot-tagged condensin. The red arrowhead demarks the initial location of the fluorescent condensin complex on the DNA, and time is indicated in the upper left corner.

This video shows an example of condensin (unlabeled) translocation along a double-tethered DNA molecule while pulling a second λ-DNA substrate provided in trans. The DNA is stained with YoYo1, and the location of the trans DNA substrate is revealed as the region of locally high YoYo1 signal intensity. The red arrowhead demarks the initial location of the trans DNA, and time is indicated in the upper left corner.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Marinova for assistance with the construction of condensin expression constructs; D. D’Amours (University of Montreal) for plasmids and yeast strains; members of the Haering, Greene, and Dekker laboratories for comments on the manuscript; and the EMBL Electron Microscopy Facility and Proteomics Core Facility for support. E.C.G. was funded by a MIRA (Maximizing Investigators’ Research Award) grant from the National Institutes of Health (R35GM118026). C.H.H. was supported by EMBL and the European Research Council (ERC) Consolidator Grant CondStruct (ERC-2015-CoG 681365). C.D. was supported by the ERC Advanced Grant SynDiv (ERC-ADG-2014 669598) and the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO/OCW) (as part of the Frontiers of Nanoscience program). T.T. was supported by fellowships from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science and the Uehara Memorial Foundation. S.B. was supported by an EIPOD (EMBL Interdisciplinary Postdocs) fellowship under Marie Curie Actions (COFUND). J.M.E. was supported by a European Molecular Biology Organization short-term fellowship. Data described in this manuscript are archived in the Greene laboratory at Columbia University and will be provided on request.

Author contributions: T.T. designed and conducted single-molecule experiments and data analysis. S.B. purified condensin complexes and conducted bulk biochemical measurements and electron microscopy analysis. J.M.E. designed and implemented single-molecule experiments. All authors discussed the experimental findings and cowrote the manuscript.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Hirano T. Cell. 2016;164:847–857. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uhlmann F. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2016;17:399–412. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang CE, Milutinovich M, Koshland D. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2005;360:537–542. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nasmyth K, Haering CH. Annu Rev Genet. 2009;43:525–558. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102108-134233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haering CH, Gruber S. Cell. 2016;164:326–326.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hauk G, Berger JM. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2016;36:85–96. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2016.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guacci V, et al. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1993;58:677–685. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1993.058.01.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirano T, Mitchison TJ, Swedlow JR. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1995;7:329–336. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(95)80087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peterson CL. Cell. 1994;79:389–392. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90247-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Niki H, et al. EMBO J. 1992;11:5101–5109. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05617.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dekker J, Mirny L. Cell. 2016;164:1110–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nasmyth K. Annu Rev Genet. 2001;35:673–745. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.35.102401.091334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Riggs AD. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1990;326:285–297. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1990.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alipour E, Marko JF. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:11202–11212. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goloborodko A, Imakaev MV, Marko JF, Mirny L. eLife. 2016;5:e14864. doi: 10.7554/eLife.14864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goloborodko A, Marko JF, Mirny LA. Biophys J. 2016;110:2162–2168. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.02.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fudenberg G, et al. Cell Rep. 2016;15:2038–2049. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.04.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naumova N, et al. Science. 2013;342:948–953. doi: 10.1126/science.1236083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang X, Brandão HB, Le TB, Laub MT, Rudner DZ. Science. 2017;355:524–527. doi: 10.1126/science.aai8982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Badrinarayanan A, Reyes-Lamothe R, Uphoff S, Leake MC, Sherratt DJ. Science. 2012;338:528–531. doi: 10.1126/science.1227126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Minnen A, et al. Cell Rep. 2016;14:2003–2016. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.01.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng TM, et al. eLife. 2015;4:e05565. doi: 10.7554/eLife.05565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Piazza I, et al. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2014;21:560–568. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson DE, Losada A, Erickson HP, Hirano T. J Cell Biol. 2002;156:419–424. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200111002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kimura K, Hirano T. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:11972–11977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.220326097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greene EC, Wind S, Fazio T, Gorman J, Visnapuu ML. Methods Enzymol. 2010;472:293–315. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(10)72006-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stigler J, Çamdere GO, Koshland DE, Greene EC. Cell Rep. 2016;15:988–998. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davidson IF, et al. EMBO J. 2016;35:2671–2685. doi: 10.15252/embj.201695402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qian H, Sheetz MP, Elson EL. Biophys J. 1991;60:910–921. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82125-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strick TR, Kawaguchi T, Hirano T. Curr Biol. 2004;14:874–880. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eeftens JM, Bisht S, Kerssemakers J, Haering CH, Dekker C. BioRxiv 149138 [Preprint] 2017 Jun 15; https://doi.org/10.1101/149138.

- 32.Pyle AM. Annu Rev Biophys. 2008;37:317–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singleton MR, Dillingham MS, Wigley DB. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:23–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.052305.115300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang W. Annu Rev Biophys. 2010;39:367–385. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.093008.131415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seidel R, Bloom JG, Dekker C, Szczelkun MD. EMBO J. 2008;27:1388–1398. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eeftens JM, et al. Cell Rep. 2016;14:1813–1818. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.01.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Soh YM, et al. Mol Cell. 2015;57:290–303. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bürmann F, et al. Mol Cell. 2017;65:861–872.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim H, Loparo JJ. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10200. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Purification of budding yeast condensin holocomplexes. (A) Size exclusion chromatograms of wild-type and ATPase-deficient Smc2(Q147L)–Smc4(Q302L) condensin complexes. (B) Analysis of peak fractions (grey bar) of the wild-type condensin purification by SDS PAGE and Coomassie staining.

Fig. S2. Condensin can reversibly compact single-tethered DNA curtains. (A) Schematic of the single-tethered DNA curtain assay used to test for DNA compaction by unlabeled condensin. (B) Still images showing the YoYo1-stained DNA before addition of wild-type condensin, after a 20-minute incubation with 10 nM condensin and 4 mM ATP, and still images after chasing the reactions with 500 mM NaCl. Note that the integrated signal intensity of the extended and compacted DNA molecules should not be compared to one another due the change in the location of the DNA with respect to the penetration depth of the evanescent field. (C) Still images showing the YoYo1-stained DNA before addition of wild-type condensin, after a 20-minute incubation with 10 nM condensin and 4 mM ATP S. (D) Still images showing the YoYo1-stained DNA before addition of ATPase deficient condensin, after a 20-minute incubation (in the absence of buffer flow) with 10 nM ATPase-deficient condensin mutant and 4 mM ATP.

Fig. S3. Condensin labeling with quantum dots. (A) Native composite agarose-acrylamide gel electrophoresis of wild-type condensin complexes upon addition of Qdots coupled to antibodies directed against the HA3 epitope tag at the C terminus of the Brn1 kleisin condensin subunit. (B) Effect of increasing ratios of anti-HA Qdot on the ATPase hydrolysis rate by wild-type condensin complexes (0.1 μM) in the presence of 6.4-kb linear DNA (240 nM) at saturated ATP concentrations (5 mM). (C) Nick ligation assay of a 6.4-kb circular DNA (1 nM) with wild-type condensin complexes alone and in the presence of an equimolar amount of anti-HA Qdot.

Fig. S4. Condensin exhibits no motor activity in reactions with ATPγS. (A) Kymograph showing condensin bound to DNA in the presence of 4 mM ATPγS. (B) Examples of particle tracking data, and (C) MSD plots for data collected with wild-type condensin in reactions with 4 mM ATPγS.

Fig. S5. Condensin pauses prior to initiating translocation. (A) Kymograph highlighting the initial pause (τpause) prior to the initiation of translocation (also see Fig. 2C). (B) Histogram showing the distribution of initial pause times prior to initiating translocation for reactions containing 4 mM ATP.

Fig. S6. Condensin’s DNA-binding properties. (A) Distribution of binding lifetimes for translocating condensin complexes. (B) Scatter plot showing that there is no apparent correlation between condensin translocation velocity and processivity. All data shown in this figure reflect results from experiments conducted in the presence of 4 mM ATP.

Fig. S7. ATP concentration dependence of condensin translocation characteristics. (A) Condensin translocation velocity versus ATP concentration for data collected at room temperature (~25°C). The data are fit to the Michaelis-Menton equation to extract the kinetic parameters Km and vmax. (B) Condensin processivity at different ATP concentrations, as indicated. (C) Initial condensin pause times (τpause) prior to initiating translocation at different ATP concentrations. For each graph, error bars represent standard deviations calculated by boot strap analysis.

Data S1. Particle tracking data for condensin translocation. This PDF file presents all of the raw data pertaining to Fig. 3E for condensin translocation on double-tethered DNA curtains. Each of the data panels (491 total) contains a raw kymograph displaying the movement on condensin on the DNA, a corresponding graph of the particle tracking data for the kymograph, and a linear fit to the tracking data. The slope of the linear fit, reflecting the average velocity for the condensin shown in the kymograph, is also shown.

This PDF file presents all of the raw data pertaining to Fig. 4D for condensin translocation on double-tethered DNA curtains while bound to a second DNA in trans. Each of the data panels (102 total) contains a raw kymograph displaying the movement on condensin on the DNA, a corresponding graph of the particle tracking data for the kymograph, and a linear fit to the tracking data. The slope of the linear fit, reflecting the average velocity for the condensin shown in the kymograph, is also shown.

This video shows a typical example of a ~48-kb double-tethered DNA molecule (unlabeled) bound by quantum dot-tagged condensin. The red arrowhead demarks the initial location of the fluorescent condensin complex on the DNA, and time is indicated in the upper left corner.

This video shows an example of condensin (unlabeled) translocation along a double-tethered DNA molecule while pulling a second λ-DNA substrate provided in trans. The DNA is stained with YoYo1, and the location of the trans DNA substrate is revealed as the region of locally high YoYo1 signal intensity. The red arrowhead demarks the initial location of the trans DNA, and time is indicated in the upper left corner.