Abstract

Background

Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR), lymphocyte to monocyte ratio (LMR) and modified Glasgow prognostic score (mGPS) are useful prognostic markers based on host-related systemic inflammatory response. They have been shown as independent prognostic biomarkers in various cancers, including non-small cell lung cancer. However, there has been little evidence for a specific population of pulmonary adenocarcinoma without active epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed 159 patients who met the following criteria: histologically or cytologically diagnosed adenocarcinoma, confirmed wild-type EGFR, started first-line cytotoxic chemotherapy between July 2007 and March 2017 at our hospital, and c-stage IIIB or IV. We compared overall survival (OS) between dichotomized groups by the optimal cut-off points of NLR and LMR, and mGPS 0 - 1 vs. 2. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard analyses also detected prognostic factors for OS.

Results

As favorable prognostic factors for OS, multivariate analysis detected Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) 0 - 1 (hazard ratio (HR) 3.43, 95% confidence interval (CI): 2.12 - 5.53; P < 0.01), LMR ≥ 1.97 (HR 0.39, 95% CI: 0.21 - 0.72; P < 0.01) and mGPS 0 - 1 (HR 1.95, 95% CI: 1.20 - 3.16; P < 0.01). The OS of LMR ≥ 1.97 and mGPS 0 - 1 groups were significantly longer than those of LMR < 1.97 and mGPS 2 groups, respectively. We divided 159 patients into three groups, both LMR ≥ 1.97 and mGPS 0 - 1, either LMR ≥ 1.97 or mGPS 0 - 1 and both LMR < 1.97 and mGPS 2. The OS of both LMR < 1.97 and mGPS 2 was significantly shorter than the other two groups. After adjustment for age, sex, ECOG PS, sodium, alkaline phosphatase and NLR, multivariate analysis found both LMR < 1.97 and mGPS 2 as an independent poor prognostic combination in comparison with both LMR ≥ 1.97 and mGPS0-1 (HR 5.98, 95% CI: 2.64 - 13.5; P < 0.01).

Conclusions

LMR and mGPS are independent prognostic markers for pulmonary adenocarcinoma with wild-type EGFR. Combination of LMR and mGPS can stratify patients according to prognosis.

Keywords: Lymphocyte to monocyte ratio, Modified Glasgow prognostic score, Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, Non-small cell lung cancer, Adenocarcinoma, Wild-type epidermal growth factor receptor, Chemotherapy, Overall survival

Introduction

Adenocarcinoma has been the most common histology of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Globally, the incidence rates of this histological subtype in men have started to stabilize during the mid-1980s in some countries and regions, but those in women steadily continue to increase [1, 2]. In Japan, the incidence rates of adenocarcinoma have continuously increased regardless of sex [3]. In clinical practice, adenocarcinoma is categorized into two genetic subsets by driver mutations such as epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) rearrangement. Approximately 50% and 3% of Asian patients with adenocarcinoma have activated EGFR mutation and ALK rearrangement, respectively [4, 5]. Treatment strategy is remarkably different according to these genetic subsets. For patients with adenocarcinoma harboring a driver mutation, suitable tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) is prioritized in terms of efficacy and toxicity. On the other hand, for adenocarcinoma without any driver mutations, conventional cytotoxic chemotherapy or immune check-point inhibitor (ICI) is considered.

Host-related systemic inflammatory response (SIR) is one of the most important factors contributing to development and progression of tumors [6-8]. There have been remarkably increasing studies that demonstrated the prognostic value of various SIR-based scoring systems. These studies adopted markers of the inflammatory response such as C-reactive protein (CRP) level, neutrophil, lymphocyte and monocyte counts. Especially, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and lymphocyte to monocyte ratio (LMR) are easily calculated from venous circulating leukocyte count and differentiation. On the other hand, modified Glasgow prognostic score (mGPS) is categorized into three classes based on CRP and serum albumin concentration, and represents not only SIR status but also nutritional status. In various cancers, including advanced NSCLC, higher NLR [9-11], lower LMR [12, 13] and Glasgow prognostic score (GPS) class 2 [14-17] are associated with poorer prognosis. However, little has been known about these three prognostic tools for a specific genetic subset of adenocarcinoma with wild-type EGFR.

In this study, we evaluated the prognostic value of NLR, LMR, mGPS and combination of these three prognostic tools in patients with pulmonary adenocarcinoma with wild-type EGFR.

Methods

Patient selection and study design

This was a retrospective and single institutional study. We enrolled the patients who met all the following criteria: 1) patients who initiated cytotoxic chemotherapy between July 2007 and March 2017, 2) histologically or cytologically diagnosed adenocarcinoma, 3) the peptide nucleic acid-locked nucleic acid PCR clamp method performed by LSI Medience Cooperation (Tokyo, Japan) [18] confirmed wild-type EGFR mutation status, 4) immunohistochemically negative or unknown ALK rearrangement, 5) c-stage IIIB or IV according to the 7th TNM classification of lung cancer by the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) [19], and 6) available blood sample within 1 week of the first day of the first-line chemotherapy. In December 2016, Japanese medical insurance approved the first-line pembrolizumab for NSCLC with tumor proportion score of PD-L1 expression ≥ 50%. Our hospital began to adopt pembrolizumab in March 2017. Clinical data we obtained from the medical records included age, sex, pathological features, laboratory data, clinical course, and treatment and efficacy. The albumin concentration, CRP, absolute counts of neutrophil, lymphocyte and monocyte were collected using routine blood tests. Creatinine clearance (Ccr) was calculated based on Cockcroft-Gault equation with addition of 0.2 mg/dL on serum creatinine values measured by the enzymatic method [20]. The NLR and LMR were calculated by dividing the pretreatment venous absolute circulating neutrophil count by the lymphocyte count, and the venous absolute circulating lymphocyte count by the monocyte count, respectively. The mGPS was formed by combination of elevated CRP and hypoalbuminemia [21]. Briefly, patients with elevated CRP (> 1.0 mg/dL) and hypoalbuminemia (< 3.5 g/dL), patients with only elevated CRP (> 1.0 mg/dL), and patients with CRP < 1.0 mg/dL with or without hypoalbuminemia were categorized as mGPS of 2, 1 and 0, respectively.

The response rate (RR), disease control rate (DCR), progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were followed as those of our previous studies [22, 23]. The data cut-off was November 30, 2017. The Osaka Police Hospital Ethics Committee approved this study. Considering the characteristic of anonymous and retrospective data, the written informed consents were waived in this study.

Data analysis

The continuous, categorical and survival data were described as the mean ± standard deviation (SD), frequency, and median (95% confidential intervals (CIs)), respectively. Fisher’s exact test and Mann-Whitney U test were used in order to compare the relative frequencies and continuous variables, respectively. Spearman’s rank-order was used to test correlation between non-parametric data of NLR and LMR. The optimal cutoff values of NLR and LMR were determined using a Bio-statistical tool Cutoff Finder, a web-based R software (http://molpath.charite.de/cutoff/) [24]. We divided our patients into two groups according to NLR, LMR and mGPS. Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test were adopted to evaluate PFS and OS, and compare survival times of two or three groups, respectively. For the multiple comparisons, P-values were corrected using the Bonferroni method. Cox proportional hazard analyses investigated independent prognostic factors, and expressed the results as hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CI. The variables with P-value < 0.1 in the preceding univariate analysis proceeded into the following multivariate analysis. All P-values were two-sided and P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed with EZR (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan), which is a graphical user interface for R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) [25].

Results

We enrolled 159 patients into this study. As of the data cut-off, 120 patients were dead. Among them, 96, 13 and 11 patients died at our hospital, at home and at other medical institutions, respectively. Thirteen were lost to follow-up after transfer to other medical institutions. Two were missing. Twenty-four were still alive. Except for one patient, all patients discontinued the first-line chemotherapy, because of PD in 83, adverse effects in 27, deteriorated comorbidity or general condition in 22, completion of pre-defined courses in 18 and patients’ refusal in eight.

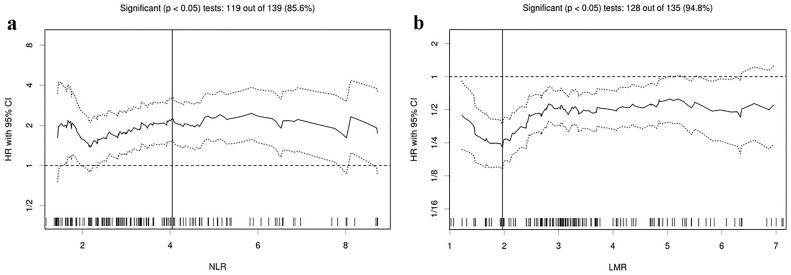

Table 1 shows backgrounds and laboratory data of 159 patients at the start of the first-line chemotherapy. By means of immunohistochemistry, 86 patients (54%) were tested for ALK rearrangement. As a result, none of them had positive ALK rearrangement. There was a significant inverse correlation between NLR and LMR (r = -0.71, P < 0.01). Table 2 presents treatment and efficacy. The Cutoff Finder found 4.05 and 1.97 as the optimum cut-off points for NLR and LMR when assessing OS (Fig. 1), and divided 159 patients into higher and lower groups. The OS of 159 patients was median 15.0 months (95% CI 11.4 - 18.2 months).

Table 1. Backgrounds and Laboratory Data at the Start of First-Line Chemotherapy.

| All, N = 159 | LMR |

mGPS |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 1.97, N = 24 | ≥ 1.97, N = 135 | P | 0 - 1, N = 120 | 2, N = 39 | P | ||

| Background | |||||||

| Age (years)a | 67.2 ± 9.0 | 67.9 ± 9.6 | 67.0 ± 8.9 | 0.45b | 67.0 ± 9.2 | 67.8 ± 8.4 | 0.54b |

| Sex (N), male/female | 114/45 | 20/4 | 94/41 | 0.22c | 83/37 | 31/8 | 0.31c |

| Stage (N), IIIB/IV | 30/129 | 1/23 | 29/106 | 0.049c | 27/93 | 3/36 | 0.057c |

| ECOG PS (N), 0 - 1/2/3 | 124/27/8 | 10/8/6 | 114/19/2 | < 0.01c | 103/15/2 | 21/12/6 | < 0.01c |

| BMIa | 21.9 ± 3.1 | 20.2 ± 3.4 | 22.2 ± 3.0 | 0.01b | 22.4 ± 2.8 | 20.4 ± 3.5 | < 0.01b |

| Laboratory dataa | |||||||

| Neu (cells/µL) | 6,004 ± 3,924 | 10,359 ± 7,068 | 5,229 ± 2,362 | < 0.01b | 5,168 ± 2,398 | 8,575 ± 6,084 | < 0.01b |

| Lym (cells/µL) | 1,673 ± 741 | 1,235 ± 1,136 | 1,751 ± 621 | < 0.01b | 1,738 ± 654 | 1,473 ± 943 | < 0.01b |

| Mono (cells/µL) | 554 ± 371 | 1,026 ± 714 | 470 ± 166 | < 0.01b | 486 ± 183 | 764 ± 638 | 0.02b |

| NLR | 4.33 ± 4.48 | 10.22 ± 8.67 | 3.28 ± 1.85 | < 0.01b | 3.38 ± 2.15 | 7.25 ± 7.57 | < 0.01b |

| LMR | 3.58 ± 1.78 | 1.28 ± 0.48 | 3.99 ±1.60 | < 0.01b | 3.91 ± 1.69 | 2.57 ± 1.69 | < 0.01b |

| Hb (g/dL) | 12.8 ± 1.6 | 12.0 ± 1.7 | 12.9 ±1.5 | < 0.01b | 13.0 ± 1.5 | 12.1 ± 1.6 | < 0.01b |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 138.7 ± 3.6 | 136.4 ± 5.0 | 139.1 ± 3.1 | < 0.01b | 139.3 ± 3.1 | 137.1 ± 4.4 | < 0.01b |

| Ccr (mL/min) | 60.9 ± 16.9 | 59.5 ± 16.1 | 61.1 ± 17.1 | 0.65 | 61.8 ± 16.1 | 58.0 ± 19.3 | 0.13b |

| LDH (IU/L) | 301 ± 456 | 396 ± 717 | 284 ± 394 | 0.07 | 257 ± 273 | 435 ± 779 | 0.10b |

| ALP (IU/L) | 317 ± 256 | 449 ± 452 | 293 ± 196 | 0.02 | 292 ± 257 | 392 ± 239 | < 0.01b |

| Alb (g/dL) | 3.6 ± 0.5 | 3.0 ± 0.5 | 3.7 ± 0.5 | < 0.01b | 3.8 ± 0.4 | 2.9 ± 0.4 | < 0.01b |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 2.6 ± 4.0 | 6.1 ± 5.3 | 2.0 ± 3.4 | < 0.01b | 1.6 ± 3.3 | 5.8 ± 4.5 | < 0.01b |

aMean ± SD. bMann-Whitney test. cFisher’s exact test. Alb: albumin; ALP: alkaline phosphatase; BMI: body mass index; Ccr: creatinine clearance; CRP: C-reactive protein; ECOG PS: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; Hb: hemoglobin; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; LMR: lymphocyte to monocyte ratio; Lym: lymphocyte; Mono: monocyte; mGPS: modified Glasgow prognostic score; Neu: neutrophil; NLR: neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio; SD: standard deviation.

Table 2. Treatment and Efficacy.

| All, N = 159 | LMR |

mGPS |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 1.97, N = 24 | ≥ 1.97, N = 135 | P | 0 - 1, N = 120 | 2, N = 39 | P | ||

| First-line regimen | |||||||

| Single or combination (N) | |||||||

| Single/combination | 4/155 | 0/24 | 4/131 | 1.00a | 4/116 | 0/39 | 0.57a |

| Platinum-based (N) | |||||||

| CDDP/CBDCA | 52/103 | 8/16 | 44/87 | 1.00a | 43/73 | 9/30 | 0.12a |

| PEM-containing (N) | 77 | 13 | 64 | 0.66a | 59 | 18 | 0.85a |

| Bev-containing (N) | 32 | 4 | 28 | 0.79a | 23 | 9 | 0.65a |

| Concurrent TRT (N) | 8 | 0 | 8 | 0.61a | 6 | 2 | 1.00a |

| First-line response | |||||||

| RR (%) (95% CI) | 40.9 (33.2 - 48.9) | 8.3 (1.0 - 27.0) | 46.7 (38.0 - 55.4) | < 0.01a | 45.0 (35.9 - 54.3) | 28.2 (15.0 - 44.9) | 0.09a |

| DCR (%) (95% CI) | 69.8 (62.0 - 76.8) | 33.3 (15.6 - 55.3) | 76.3 (68.2 - 83.2) | < 0.01a | 76.7 (68.1 - 83.9) | 48.7 (32.4 - 65.2) | < 0.01a |

| PFS (months) (95% CI) | 5.4 (4.6 - 6.3) | 2.7 (1.0 - 3.7) | 5.7 (5.3 - 6.6) | < 0.01b | 5.7 (5.2 - 6.8) | 3.1 (1.6 - 5.3) | 0.01b |

| Second or further line (N) | 96 | 5 | 91 | < 0.01a | 84 | 12 | < 0.01a |

| ICI (N) | 20 | 1 | 19 | 0.31a | 18 | 2 | 0.16a |

aFisher’s exact test. bLog-rank test. Bev: bevacizumab; CBDCA: carboplatin; CDDP: cisplatin; CI: confidence interval; DCR: disease control rate; ICI: immuno-checkpoint inhibitor; LMR: lymphocyte to monocyte ratio; mGPS: modified Glasgow prognostic score; PEM: pemetrexed; PFS: progression-free survival; RR: response rate; TRT: thoracic radiotherapy.

Figure 1.

Hazard ratios and cutoff values of NLR and LMR for overall survival. (a) NLR and (b) LMR. The vertical line designates the optimal cutoff values with the most significant (log-rank test) split. The plots were determined using the R software-based biostatistical tool, Cutoff Finder. LMR: lymphocyte to monocyte ratio; NLR: neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio; HR: hazard ratio; OS: overall survival.

As favorable prognostic factors for OS, univariate Cox hazard analysis detected Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) 0 - 1 (HR 4.77, 95% CI: 3.07 - 7.40; P < 0.01), higher sodium concentration (/10 mEq/L) (HR 0.61, 95% CI: 0.42 - 0.90; P = 0.01), NLR < 4.05 (HR 2.17, 95% CI: 1.50 - 3.13; P < 0.01), LMR ≥ 1.97 (HR 0.22, 95% CI: 0.14 - 0.36; P < 0.01) and mGPS 0 - 1 (HR 2.60, 95% CI: 1.73 - 3.90; P < 0.01). The subsequent multivariate analysis detected ECOG PS 0 - 1 (HR 3.43, 95% CI: 2.12 - 5.53; P < 0.01), LMR ≥ 1.97 (HR 0.39, 95% CI: 0.21 - 0.72; P < 0.01) and mGPS 0 - 1 (HR 1.95, 95% CI: 1.20 - 3.16; P < 0.01) (Table 3).

Table 3. Univariate and Multivariate Cox Proportional Hazard Analysis of Factors Associated With Overall Survival.

| Univariate |

Multivariate |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | |

| Age (years), < 75 vs. ≥ 75 | 1.47 | 0.97 - 2.23 | 0.07 | 1.21 | 0.78 - 1.89 | 0.39 |

| Sex, female vs. male | 1.50 | 0.99 - 2.26 | 0.054 | 1.13 | 0.73 - 1.73 | 0.59 |

| Stage IIIB vs. IV | 1.10 | 0.68 - 1.76 | 0.70 | |||

| ECOG PS, 0 - 1 vs. 2 - 4 | 4.77 | 3.07 - 7.40 | < 0.01 | 3.43 | 2.12 - 5.53 | < 0.01 |

| BMI, ≥ 18.5 vs. < 18.5 | 0.98 | 0.92 - 1.04 | 0.45 | |||

| Smoking status, NS, Ex vs. CS | 1.14 | 0.80 - 1.64 | 0.47 | |||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 0.94 | 0.83 - 1.05 | 0.28 | |||

| Ccr (mL/min) (/10) | 0.92 | 0.82 - 1.03 | 0.15 | |||

| Sodium (mEq/L) (/10) | 0.61 | 0.42 - 0.90 | 0.01 | 1.28 | 0.78 - 2.10 | 0.33 |

| LDH (IU/L) (/100) | 1.03 | 0.99 - 1.06 | 0.15 | |||

| ALP (IU/L) (/100) | 1.06 | 0.99 - 1.13 | 0.08 | 1.00 | 0.92 - 1.09 | 0.99 |

| NLR, < 4.05 vs. ≥ 4.05 | 2.17 | 1.50 - 3.13 | < 0.01 | 1.09 | 0.67 - 1.78 | 0.72 |

| LMR, < 1.97 vs. ≥ 1.97 | 0.22 | 0.14 - 0.36 | < 0.01 | 0.39 | 0.21 - 0.72 | < 0.01 |

| mGPS, 0,1 vs. 2 | 2.60 | 1.73 - 3.90 | < 0.01 | 1.95 | 1.20 - 3.16 | < 0.01 |

ALP: alkaline phosphatase; BMI: body mass index; CI: confidence interval; Ccr: creatinine clearance; CS: current smoker; ECOG PS: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; Ex: ex-smoker; HR: hazard ratio; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; mGPS: modified Glasgow prognostic score; LMR: lymphocyte to monocyte ratio; NLR: neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio; NS: non-smoker.

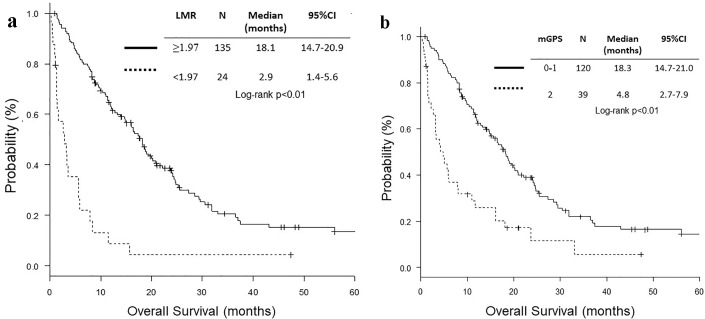

Both high LMR group (LMR ≥ 1.97) and mGPS 0 - 1 group included more patients with ECOG PS 0 - 1, higher BMI, lower neutrophil count, higher lymphocyte count, lower monocyte count, lower NLR, higher LMR, higher sodium concentration, lower ALP, higher albumin and lower CRP level (Table 1). The RR and DCR were higher in high LMR and mGPS 0 - 1 groups than in low LMR and mGPS 2 groups, respectively. High LMR and mGPS 0 - 1 groups were more likely to receive second or further chemotherapy. PFS and OS of high LMR and mGPS 0 - 1 groups were significantly longer than those of low LMR and mGPS 2 groups, respectively (Table 2 and Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves of overall survival according to LMR and mGPS. (a) LMR. (b) mGPS. LMR: lymphocyte to monocyte ratio; mGPS: modified Glasgow prognostic score.

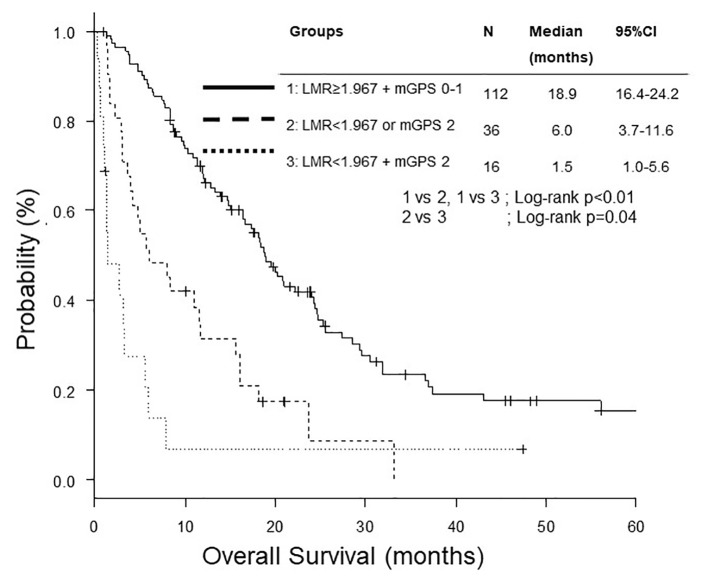

We divided 159 patients into three groups, both LMR ≥ 1.97 and mGPS 0 - 1, either LMR < 1.97 or mGPS 2, and both LMR < 1.97 and mGPS 2. The OS of both LMR < 1.97 and mGPS 2 was significantly shorter than the other two groups (Fig. 3). After adjustment for age, sex, ECOG PS, sodium, ALP and NLR, multivariate analysis found both LMR < 1.97 and mGPS 2 as a poorer prognostic combination than both LMR ≥ 1.97 and mGPS 0 - 1 (Table 4).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curves of overall survival according to combination of LMR and mGPS. LMR: lymphocyte to monocyte ratio; mGPS: modified Glasgow prognostic score.

Table 4. Cox Proportional Hazard Analysis of Overall Survival According to Combination of LMR and mGPS.

| HR | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LMR ≥ 1.97 + mGPS 0 - 1 | 1 | ||

| LMR < 1.97 or mGPS 2 | 1.65 | 0.96 - 2.83 | 0.07 |

| LMR < 1.97 + mGPS 2 | 5.98 | 2.64 - 13.5 | < 0.01 |

Adjusted for age, sex, ECOG PS, sodium, ALP and NLR. CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; mGPS: modified Glasgow prognostic score; LMR: lymphocyte to monocyte ratio.

Discussion

This study focused on a histologically and genetically specific subset of NSCLC, adenocarcinoma with wild-type EGFR. This was the first study that demonstrated both LMR and mGPS as useful prognostic markers for the specific subset of NSCLC. We also showed that combination of LMR and mGPS selected patients with poor prognosis.

Our multivariate Cox hazard analysis and comparisons of OS according to LMR and mGPS showed these two markers as independent prognostic factors for OS of those selected population. In this study, NLR was not an independent prognostic factor for OS of adenocarcinoma with wild-type EGFR. This result was contrary to that of our previous study, in which it was not LMR, but NLR that had been selected as an independent factor for OS of NSCLC harboring positive EGFR mutation [26]. Our two studies were different in the patient cohorts, genetic backgrounds and chemotherapeutic regimens. LMR has been demonstrated as a prognostic factor for OS and PFS of advanced stage patients with non-specific NSCLC [13, 27] and NSCLC with positive EGFR mutation [28] (Table 5 [13, 26-28]). On the other hand, six studies showed GPS as a prognostic factor for advanced stage of non-specific NSCLC [15, 16, 29-32]. In contrast, Zhu et al failed to detect mGPS as a significant prognostic factor for OS and PFS, and developed a new SIR-based prognostic score consisting of CRP, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and cancer antigen125 [33] (Table 6) [16, 29-34]. In our previous study, we did not collect pretreatment data of serum albumin concentration, and not analyze mGPS in patients with positive EGFR mutation [26]. To our knowledge, there was no study that had shown mGPS as a prognostic factor in these selected patients harboring driver mutation. The optimal biomarkers may vary according to tumor subtypes.

Table 5. Review of Previous Studies of LMR as a Prognostic Factor for Advanced NSCLC [13, 26-28].

| Author (year) | Country | N | Patient treatment | Cut-off | Multivariate analyses |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OS |

PFS |

|||||||

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |||||

| Lin et al (2014) [13] | China | 370 | Stage IIIB or IV, platinum-based doublet | 4.56 | 0.530 (0.409 - 0.687) | < 0.001 | 0.660 (0.512 - 0.851) | 0.001 |

| Chen et al (2015) [28] | Taiwan | 253 | EGFR mt (+) first-line EGFR-TKIs | 3.29 | 2.36 (1.66 - 3.35) | < 0.001 | 1.71 (1.14 - 2.56) | 0.009 |

| Chang et al (2017) [27] | Taiwan | 490 | Stage IV | 3.1 | 1.844 (1.212 - 1.837) | < 0.001 | NA | NA |

| Our (2017) [26] | Japan | 152 | EGFR mt (+), EGFR-TKIs | 5.09 | 0.88 (0.76 - 1.01) | 0.07 | 1.00 (0.90 - 1.12) | 0.99 |

| Our | Japan | 159 | Stage IIIB or IV, Ad, platinum-based | 1.97 | 0.39 (0.21 - 0.72) | < 0.01 | NA | NA |

Ad: adenocarcinoma; CI: confidence interval; EGFR: epidermal growth factor receptor; HR: hazard ratio; LMR: lymphocyte to monocyte ratio; mt: mutation; NA: not assessed; NSCLC: non-small cell lung cancer; PFS: progression-free survival; OS: overall survival; TKI: tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Table 6. Review of Previous Studies of GPS as a Prognostic Factor for Advanced NSCLC [16, 29-34].

| Author (year) | Country | N | Patient treatment | Variables | OS |

PFS |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |||||

| Forrest et al (2004) [29] | UK | 109 | Inoperable, platinum-based chemotherapy | GPS | 1.88 (1.25 - 2.84) | 0.002 | NA | NA |

| Meek et al (2010) [31] | UK | 56 | Inoperable | mGPS | ND | < 0.001 | NA | NA |

| Leung et al (2012) [16] | UK | 261 | Inoperable | mGPS 0, 1, 2 | 1.67 (1.28 - 2.19) | < 0.0001 | NA | NA |

| Simmons et al (2015) [32] | UK | 390 | Stage IV NSCLC (N = 288) or ES-SCLC | mGPS 0, 1, 2 | 1.67 (1.40 - 2.00) | < 0.001 | NA | NA |

| Jiang et al (2015) [34] | China | 138 | Stage IIIB or IV CDDP-based chemotherapy | 0 vs. 1 0 vs. 2 |

0.8 (0.4 - 0.9) 0.5 (0.2 - 0.9) |

0.02 | 0.8 (0.5 - 0.9) 0.6 (0.2 - 0.8) |

0.03 |

| Zhu et al (2016) [33] | China | 105 | Inoperable stage IIIB or IV, first-line chemotherapy | mGPS 0, 1, 2 | 1.19 (0.81 - 1.75) | 0.374 | 1.10 (0.79 - 1.53) | 0.579 |

| Lv et al (2017) [30] | China | 266 | Recurrence after resection, systemic chemotherapy | mGPS 0 - 1 vs. 2 | 1.47 (1.15 - 1.88) | 0.002 | NA | NA |

| Our | Japan | 159 | Stage IIIB or IV, Ad, platinum-based | mGPS 0 - 1 vs. 2 | 1.95 (1.20 - 3.16) | < 0.01 | NA | NA |

Ad: adenocarcinoma; CDDP: cisplatin; CI: confidence interval; ES-SCLC: extensive stage small cell lung cancer; GPS: Glasgow prognostic score; HR: hazard ratio; mGPS, modified Glasgow prognostic score; NA: not assessed; ND: not described; NSCLC: non-small cell lung cancer; OS: overall survival; PFS: progression-free survival.

Combination of LMR and mGPS was useful to select patients with poorer prognosis. Combination of some prognostic tools potentially stratifies patients according to their predictable prognosis. Our multivariate analysis and comparisons of survival curves demonstrated that patients with LMR < 1.97 + mGPS 2 had the worst prognosis. We oncologists should reconsider systemic chemotherapy for these selected population.

There were some limitations in this study. First, our study was so small that some other biomarkers, especially NLR, might be overlooked as significant prognostic factors. Second, our single-centered and retrospective study might include case bias.

Conclusion

LMR and mGPS are independent prognostic markers for pulmonary adenocarcinoma with wild-type EGFR. Combination of LMR and mGPS can stratify patients according to prognosis.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Yoshimi Noda, Yuki Nakatani, Kanako Nishimatsu, Shouko Ikuta, Saori Ikebe and Hideyasu Okada at the Department of Respiratory Medicine, Osaka Police Hospital for their detailed medical records, diagnosis, treatment and care of their patients.

Grant Support

None.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Cheng TY, Cramb SM, Baade PD, Youlden DR, Nwogu C, Reid ME. The international epidemiology of lung cancer: latest trends, disparities, and tumor characteristics. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11(10):1653–1671. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lortet-Tieulent J, Soerjomataram I, Ferlay J, Rutherford M, Weiderpass E, Bray F. International trends in lung cancer incidence by histological subtype: adenocarcinoma stabilizing in men but still increasing in women. Lung Cancer. 2014;84(1):13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Toyoda Y, Nakayama T, Ioka A, Tsukuma H. Trends in lung cancer incidence by histological type in Osaka, Japan. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2008;38(8):534–539. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyn072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu L, Liu J, Shao D, Deng Q, Tang H, Liu Z, Chen X. et al. Comprehensive genomic profiling of lung cancer using a validated panel to explore therapeutic targets in East Asian patients. Cancer Sci. 2017;108(12):2487–2494. doi: 10.1111/cas.13410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shi Y, Au JS, Thongprasert S, Srinivasan S, Tsai CM, Khoa MT, Heeroma K. et al. A prospective, molecular epidemiology study of EGFR mutations in Asian patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer of adenocarcinoma histology (PIONEER) J Thorac Oncol. 2014;9(2):154–162. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;420(6917):860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature01322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mantovani A, Romero P, Palucka AK, Marincola FM. Tumour immunity: effector response to tumour and role of the microenvironment. Lancet. 2008;371(9614):771–783. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60241-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Proctor MJ, Morrison DS, Talwar D, Balmer SM, Fletcher CD, O’Reilly DS, Foulis AK. et al. A comparison of inflammation-based prognostic scores in patients with cancer. A Glasgow Inflammation Outcome Study. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(17):2633–2641. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gu XB, Tian T, Tian XJ, Zhang XJ. Prognostic significance of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2015;5:12493. doi: 10.1038/srep12493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peng B, Wang YH, Liu YM, Ma LX. Prognostic significance of the neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(3):3098–3106. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yin Y, Wang J, Wang X, Gu L, Pei H, Kuai S, Zhang Y. et al. Prognostic value of the neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in lung cancer: A meta-analysis. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2015;70(7):524–530. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2015(07)10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu P, Shen H, Wang G, Zhang P, Liu Q, Du J. Prognostic significance of systemic inflammation-based lymphocyte- monocyte ratio in patients with lung cancer: based on a large cohort study. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e108062. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin GN, Peng JW, Xiao JJ, Liu DY, Xia ZJ. Prognostic impact of circulating monocytes and lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio on previously untreated metastatic non-small cell lung cancer patients receiving platinum-based doublet. Med Oncol. 2014;31(7):70. doi: 10.1007/s12032-014-0070-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fan H, Shao ZY, Xiao YY, Xie ZH, Chen W, Xie H, Qin GY. et al. Comparison of the Glasgow Prognostic Score (GPS) and the modified Glasgow Prognostic Score (mGPS) in evaluating the prognosis of patients with operable and inoperable non-small cell lung cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2016;142(6):1285–1297. doi: 10.1007/s00432-015-2113-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang AG, Lu HY. The Glasgow prognostic score as a prognostic factor in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer treated with cisplatin-based first-line chemotherapy. J Chemother. 2015;27(1):35–39. doi: 10.1179/1973947814Y.0000000188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leung EY, Scott HR, McMillan DC. Clinical utility of the pretreatment glasgow prognostic score in patients with advanced inoperable non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7(4):655–662. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318244ffe1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Umihanic S, Umihanic S, Jamakosmanovic S, Brkic S, Osmic M, Dedic S, Ramic N. Glasgow prognostic score in patients receiving chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer in stages IIIb and IV. Med Arch. 2014;68(2):83–85. doi: 10.5455/medarh.2014.68.83-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagai Y, Miyazawa H, Huqun, Tanaka T, Udagawa K, Kato M, Fukuyama S. et al. Genetic heterogeneity of the epidermal growth factor receptor in non-small cell lung cancer cell lines revealed by a rapid and sensitive detection system, the peptide nucleic acid-locked nucleic acid PCR clamp. Cancer Res. 2005;65(16):7276–7282. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rami-Porta R, Crowley JJ, Goldstraw P. The revised TNM staging system for lung cancer. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;15(1):4–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ando Y, Minami H, Saka H, Ando M, Sakai S, Shimokata K. Adjustment of creatinine clearance improves accuracy of Calvert’s formula for carboplatin dosing. Br J Cancer. 1997;76(8):1067–1071. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Proctor MJ, Talwar D, Balmar SM, O’Reilly DS, Foulis AK, Horgan PG, Morrison DS. et al. The relationship between the presence and site of cancer, an inflammation-based prognostic score and biochemical parameters. Initial results of the Glasgow Inflammation Outcome Study. Br J Cancer. 2010;103(6):870–876. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Minami S, Ogata Y, Ihara S, Yamamoto S, Komuta K. Retrospective analysis of outcomes and prognostic factors of chemotherapy for small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer (Auckl) 2016;7:35–44. doi: 10.2147/LCTT.S100184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Minami S, Ogata Y, Ihara S, Yamamoto S, Komuta K. Outcomes and prognostic factors of chemotherapy for patients with locally advanced or metastatic pulmonary squamous cell carcinoma. Lung Cancer (Auckl) 2016;7:99–110. doi: 10.2147/LCTT.S107560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Budczies J, Klauschen F, Sinn BV, Gyorffy B, Schmitt WD, Darb-Esfahani S, Denkert C. Cutoff Finder: a comprehensive and straightforward Web application enabling rapid biomarker cutoff optimization. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e51862. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48(3):452–458. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Minami S, Ogata Y, Ihara S, Yamamoto S, Komuta K. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts overall survival of advanced non-small cell lung cancer harboring mutant epidermal growth factor receptor. World J Oncol. 2017;8(6):180–187. doi: 10.14740/wjon1069w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang YP, Chen YM, Lai CH, Lin CY, Fang WF, Huang CH, Li SH. et al. The impact of de novo liver metastasis on clinical outcome in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. PLoS One. 2017;12(6):e0178676. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0178676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen YM, Lai CH, Chang HC, Chao TY, Tseng CC, Fang WF, Wang CC. et al. Baseline and trend of lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio as prognostic factors in epidermal growth factor receptor mutant non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with first-line epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0136252. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Forrest LM, McMillan DC, McArdle CS, Angerson WJ, Dunlop DJ. Comparison of an inflammation-based prognostic score (GPS) with performance status (ECOG) in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy for inoperable non-small-cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2004;90(9):1704–1706. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lv Y, Pan Y, Dong C, Liu P, Zhang C, Xing D. Modified glasgow prognostic score at recurrence predicts poor survival in resected Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) patients. Med Sci Monit. 2017;23:3780–3788. doi: 10.12659/MSM.903710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meek CL, Wallace AM, Forrest LM, McMillan DC. The relationship between the insulin-like growth factor-1 axis, weight loss, an inflammation-based score and survival in patients with inoperable non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Nutr. 2010;29(2):206–209. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2009.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simmons CP, Koinis F, Fallon MT, Fearon KC, Bowden J, Solheim TS, Gronberg BH. et al. Prognosis in advanced lung cancer—A prospective study examining key clinicopathological factors. Lung Cancer. 2015;88(3):304–309. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu L, Li X, Shen Y, Cao Y, Fang X, Chen J, Yuan Y. A new prognostic score based on the systemic inflammatory response in patients with inoperable non-small-cell lung cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2016;9:4879–4886. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S107279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jiang AG, Chen HL, Lu HY. The relationship between Glasgow Prognostic Score and serum tumor markers in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:386. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1403-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]