Abstract

Background

The aim of the study was to evaluate the radiation sensitizing ability of ERK1/2, PI3K-AKT and JNK inhibitors in highly radiation resistant and metastatic B16F10 cells which carry wild-type Ras and Braf.

Methods

Mouse melanoma cell line B16F10 was exposed to 1.0, 2.0 and 3.0 Gy of electron beam radiation. Phosphorylated ERK1/2, AKT and JNK levels were estimated by ELISA. Cells were exposed to 2.0 and 3.0 Gy of radiation with or without prior pharmacological inhibition of ERK1/2, AKT as well as JNK pathways. Cell death induced by radiation as well as upon inhibition of these pathways was measured by TUNEL assay using flow cytometry.

Results

Exposure of B16F10 cells to 1.0, 2.0 and 3.0 Gy of electron beam irradiation triggered an increase in all the three phosphorylated proteins compared to sham-treated and control groups. B16F10 cells pre-treated with either ERK1/2 or AKT inhibitors equally enhanced radiation-induced cell death at 2.0 as well as 3.0 Gy (P < 0.001), while inhibition of JNK pathway increased radiation-induced cell death to a lesser extent. Interestingly combined inhibition of ERK1/2 or AKT pathways did not show additional cell death compared to individual ERK1/2 or AKT inhibition. This indicates that ERK1/2 or AKT mediates radiation resistance through common downstream molecules in B16F10 cells.

Conclusions

Even without activating mutations in Ras or Braf genes, ERK1/2 and AKT play a critical role in B16F10 cell survival upon radiation exposure and possibly act through common downstream effector/s.

Keywords: Radiation, Pathway inhibitors, Cell signalling, Cell death

Introduction

Ionizing radiation is a potent DNA damaging agent that interacts with cellular DNA and induces lesions in the irradiated cells and prevents cell proliferation and induces cell death by apoptosis or necrosis depending on the radiation dose. Due to its cell killing effect, radiation therapy is widely used as a primary source of treatment for numerous types of cancers. Tumor control could be best achieved with radiation therapy if the tumor is well localized. With the advancement in radiation treatment modalities, by precise physical and biological targeting, cancer could be more effectively treated with radiation therapy with minimal normal tissue damaging [1]. However, the major setback to use radiation therapy for several types of cancer is the development of radiation resistance.

Studies have shown that exposure of tumor cells to therapeutic doses of radiation activates cell survival signaling pathways such as EGFR-RAS [2-5] and its downstream molecules such as ERK1/2, PI3K-AKT, JNK, etc. apart from several other signaling molecules [4, 6, 7]. Among these, ERK1/2 and AKT pathways are well known for their pro-survival and pro-proliferative activities, whereas JNK is a stress responsive pathway. Activation of these pathways further leads to the activation of multiple transcription factors, pro- and antiapoptotic proteins, cell cycle check point proteins, etc. [4, 6, 8]. Ionizing radiation has been shown to activate these signaling pathways in different intensities and in a cell type-dependent manner [6]. Activation of ERK1/2 triggers G2 checkpoint which is considered protective from radiation-induced cell death [8, 9], while activated AKT is known to promote DNA repair and inhibition of apoptosis induction [10]. Thus apart from direct cytotoxic effect, the exposure of cancer cells to therapeutic doses of radiation also enhances the survival and proliferation of a fraction of cells which ultimately leads to radiation resistance and therapeutic inefficacy.

Generally it is arguable that inhibition of these pro-survival and pro-proliferative pathways activated due to radiation exposure has the great potential to improve the radiation sensitization of cancer cells. Since activation of these pathways is also dependent on the mutational status of Ras or Braf [2, 11], inhibition of epidermal growth factor receptor or its individual downstream pathways such as ERK1/2 or AKT signaling has been evaluated for their radio-sensitizing potential and found effective in certain cases both in vitro as well as in vivo studies with Ras or Braf mutations [12-18]. Radiation sensitization studies with cancer cells bearing wild-type Ras and Braf are very limited [19]. In the present study, using a highly radiation resistant and metastatic B16F10 cells which carry wild-type Ras and Braf [20-24], it was shown that phosphorylated ERK1/2, AKT as well as JNK levels were significantly increased upon radiation exposure. Targeted inhibition of ERK1/2 and AKT pathways moderately but equally enhanced radiation-induced cell death while inhibition of JNK enhanced radiation-induced cell death to a lesser extent. However, combined inhibition of both ERK1/2 and AKT did not increase additional cell death, indicating that the radiation-induced cell death in B16F10 cells is possibly mediated by common downstream effector molecules of ERK1/2 and AKT.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and treatment conditions

Mouse melanoma cell line B16F10 was procured from National Centre for Cell Science, Pune, India as well as from Department of Radiation Biology and Toxicology, School of Life Sciences, Manipal, India. Cells were cultured in DMEM media supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 10% fetal bovine serum and 1 µg/mL of penicillin and streptomycin and maintained at 37 °C in a humidified incubator of 5% CO2. ERK1/2 activity was inhibited using U0126, PI3K-AKT kinase activity was inhibited using LY294002 and JNK activity was inhibited using SP600125 (all were from Calbiochem, USA). All the inhibitors were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide, aliquoted for single use and stored at -20 °C.

Radiation treatment

Cells (5 × 104) were seeded in 12.5 cm2 culture flask and incubated for 24 h to allow for cell attachment and recovery. Media was aspirated and replaced with media containing the desired concentration of drug. After 24 h of incubation, cells in the flask were treated with 1.0, 2.0 and 3.0 Gy electron beam radiation (Microtron Centre, Mangalore University, India). After irradiation, cells were further incubated with drugs for either 4 or 24 h depending on the experimental requirement. To mimic the radiation treatment procedure, a batch of cultured cells were carried to radiation room in a similar way to radiation treatment groups but were not exposed to radiation. These sham-irradiated cells were used for comparing the actual effects of treatment along with control B16F10 cells.

Estimation of phosphorylated ERK1/2, AKT and JNK

Cells (1 × 105) were seeded in 12.5 cm2 culture flasks and allowed for cell attachment and recovery. After 24 h of incubation, media was aspirated and replaced with media containing 20 µM concentrations of U0126, LY294002 or without drugs. After 24 h, cells were irradiated as explained earlier. After 4 h of irradiation, cultures were washed with cold PBS, and cells were harvested by scraping with a rubber policeman. Collected cells were centrifuged at 4 °C for 5 min and the cell pellets were treated with ice-cold cell extraction buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitor for 30 min, on ice, with vortexing at 10 min intervals. Cell extractions were micro-centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatants were collected and stored at -80 °C until analysis. Phosphorylated ERK1/2 (p-ERK1/2; Cat No. KHO0091), phosphorylated AKT (p-AKT; Cat No. KHO0541), and phosphorylated JNK (p-JNK; Cat No.KHO0131) - all from Invitrogen - were measured according to manufacturer’s protocols.

Evaluation of cell death

Cells (1 × 105) were seeded in 12.5 cm2 culture flasks and allowed for cell attachment and recovery. After 24 h of incubation, media was aspirated and replaced with media containing 20 µM concentrations of U0126, LY294002 or SP600125. After 24 h, cells were irradiated as explained earlier. After 24 h of irradiation, amount of cell death in different groups was measured using TUNEL assay (EMD Millipore, Cat. No.4500-0121). Briefly, cells were detached from the flasks and washed twice with PBS and fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde in PBS on ice for 1 h, suspended in ice-cold ethanol (70%) and stored overnight at -20 °C. Cells were then washed twice in wash buffer and suspended in DNA labeling mix containing TdT enzyme and Brd-UTP. Samples were incubated in a humidified atmosphere for 1 h at 37 °C in the dark, washed in rinsing buffer, suspended in anti-BrdU staining mix containing anti-BrdU-TRITC and incubated for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. At the end of incubation, final volume was adjusted to 200 µL with rinsing buffer and quantified using the flow cytometry system (Guava EasyCyte, EMD Millipore) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. The data were analyzed using the EasyCyte software module (EMD Millipore).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± SE from three independent experiments. Statistical analyses were performed by one-way ANOVA. P < 0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Exposure of B16F10 cells to radiation increased p-ERK1/2, p-AKT and p-JNK levels

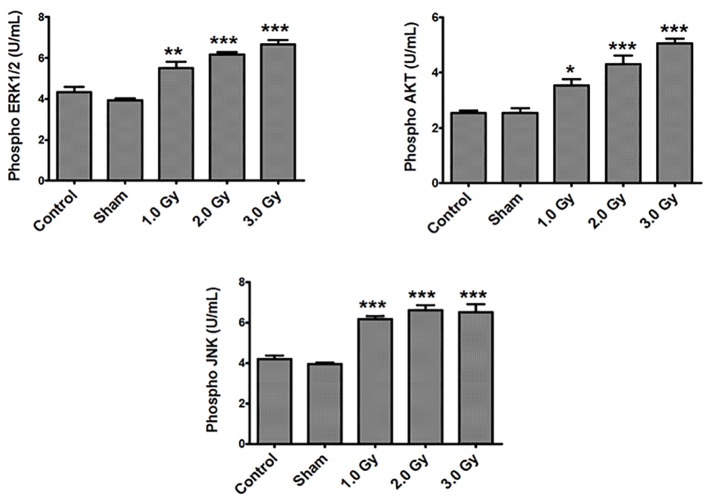

Control B16F10 tumor cells, sham-irradiated cells and cells exposed to 1.0, 2.0 and 3.0 Gy of radiation were used to measure p-ERK1/2, p-AKT as well as p-JNK levels. No significant differences in any of the measured phosphorylated proteins were observed between control and sham-treated groups. However, exposure of B16F10 cells to 1.0, 2.0 and 3.0 Gy of electron beam irradiation triggered an increase in all the three phosphorylated proteins compared to sham-treated and control groups (Fig. 1). Phosphorylated ERK1/2 and p-AKT were increased in a dose-dependent manner upon exposure to 1.0, 2.0 and 3.0 Gy of radiation at 4 h of post-irradiation (P < 0.01 to 0.0001). Increase in p-JNK levels were also significant upon exposure to 1.0, 2.0 and 3.0 Gy of radiation compared to control and sham-irradiated groups, although the increase was dose-independent.

Figure 1.

Exposure of B16F10 cells to radiation increased phosphorylated ERK1/2, AKT and JNK levels. There were no significant differences in any of the measured phosphorylated proteins between control and sham-treated groups. Phosphorylated ERK1/2 levels - control or sham versus 1.0 (P < 0.001); control or sham versus 2.0 and 3.0 Gy (P < 0.0001). Phosphorylated AKT levels - control versus 1.0 Gy (P < 0.01); sham versus 1.0 Gy (P < 0.001); control or sham versus 2.0 and 3.0 Gy (P < 0.0001). Phosphorylated JNK levels - control or sham versus 1.0, 2.0 and 3.0 Gy (P < 0.0001).

Inhibition of ERK1/2 and AKT equally enhanced radio-sensitivity of B16F10 cells exposed to 2.0 and 3.0 Gy electron beam radiation

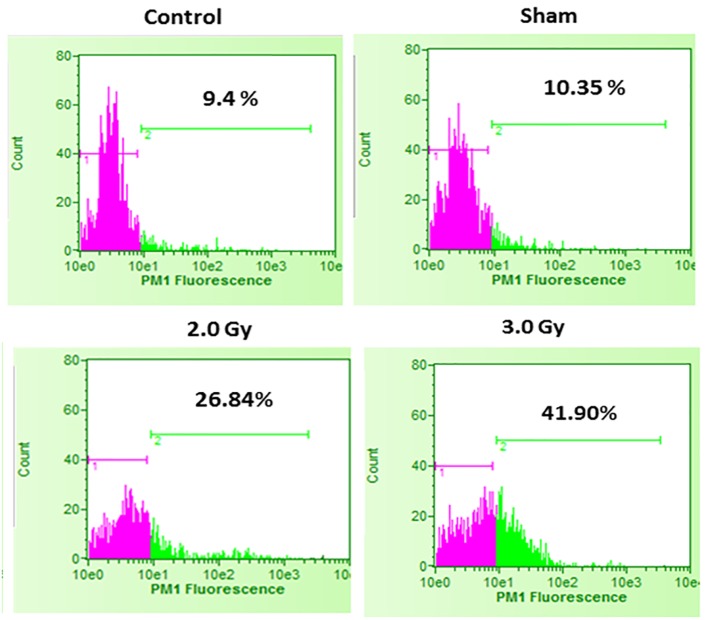

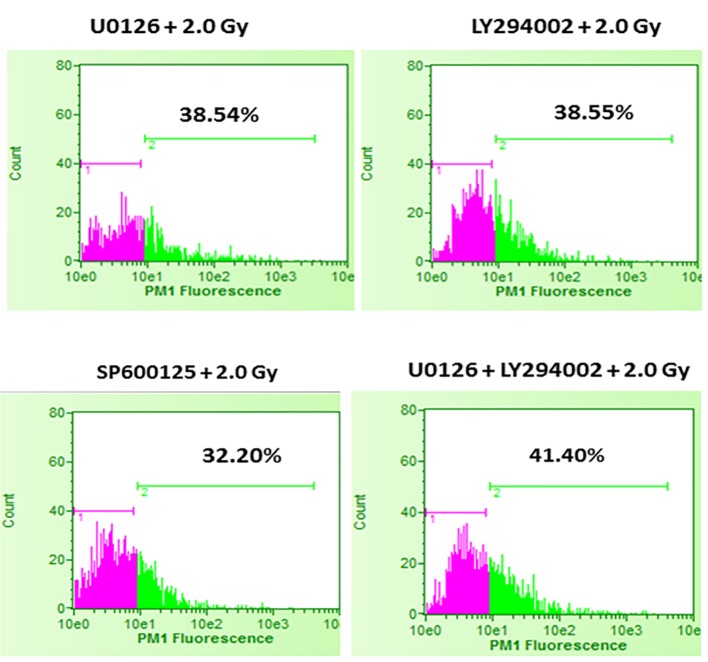

In the first set of experiments, B16F10 cells were treated with 20 µM concentrations of U0126, LY294002 and SP600125, 24 h before exposing cells to 2.0 Gy of radiation. Treatment with 20 µM concentration of either U0126, LY294002 or SP600125 alone did not show significant increase in cell death at 48 h after drug treatment compared to control and sham group (data not shown). Treatment of B16F10 cells with 2.0 Gy of radiation produced significant amount of cell death compared to control groups (P < 0.0001, Fig. 2). B16F10 cells pre-treated with 20 µM U0126 showed further increase in cell death compared to 2.0 Gy radiation alone group (P < 0.001, Figs. 2 and 3). Interestingly, B16F10 cells pre-treated with 20 µM LY294002 also yielded similar results comparable to treatment with U0126 (Figs. 2 and 3). The enhancement in cell death induced by both U0126 and LY294002 was about 43% higher compared to 2.0 Gy radiation alone (Fig. 4). However, cells pre-treated with 20 µM SP600125 enhanced radiation-induced cell death to a limited extent, although the values are statistically significant (P < 0.01) compared to 2.0 Gy radiation alone group (Figs. 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

Cell death in control B16F10 cells, sham-irradiated cells, 2.0 Gy irradiated cells and 3.0 Gy irradiated cells. Compared to control and sham-irradiated cells, 2.0 Gy and 3.0 Gy of irradiation significantly increased cell death (P < 0.0001). Further, compared to 2.0 Gy irradiation, irradiation with 3.0 Gy significantly increased cell death (P < 0.001). Pink color indicates viable cell fraction and green color indicates dead cell fraction.

Figure 3.

Effect of inhibition of ERK1/2, AKT and JNK pathways prior to 2.0 Gy radiation exposures of B16F10 cells. B16F10 cells were treated with 20 µM concentrations of U0126, LY294002 and SP600125, 24 h before exposing cells to 2.0 Gy of radiation. Pink color indicates viable cell fraction and green color indicates dead cell fraction. Cell death in U0126 + 2.0 Gy group versus 2.0 Gy alone: P < 0.0001; cell death in LY294002 + 2.0 Gy group versus 2.0 Gy alone: P < 0.0001; cell death in SP600125 + 2.0 Gy group versus 2.0 Gy alone: P < 0.01; cell death in U0126 + LY29400 + 2.0 Gy versus 2.0 Gy alone: P < 0.001.

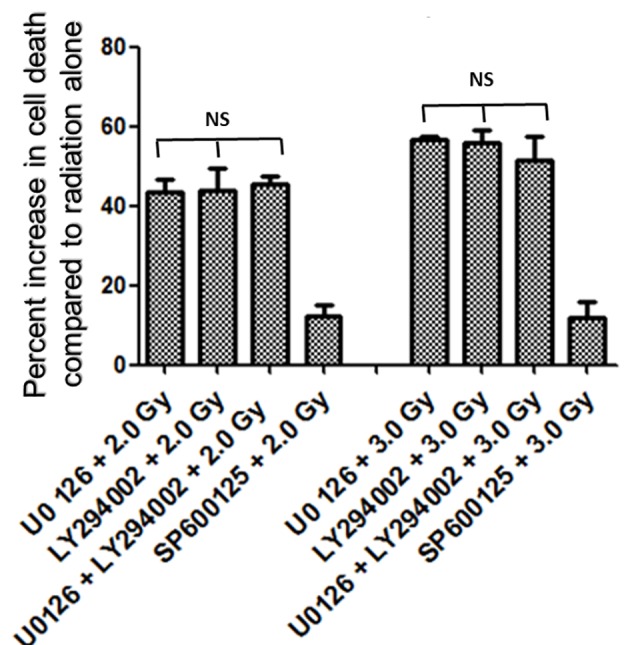

Figure 4.

Increase in amount of cell death (%) with inhibitors of ERK1/2, AKT and JNK pathways. Inhibition of either ERK1/2 or AKT pathways enhanced radiation-induced cell death almost equally (about 43% at 2.0 Gy and about 55% at 3.0 Gy), while inhibition of JNK enhanced relatively low amount of cell death (about 12%) at 2.0 Gy as well as at 3.0 Gy. Combined inhibition of U0126 + LY294002 prior to radiation treatment enhanced radiation induced cell death at 2.0 Gy by 45% and at 3.0 Gy by 51%. Overall no significant difference in percent increase in cell death was observed between U0126, LY294002 or their combination both with 2.0 Gy and 3.0 Gy treatments.

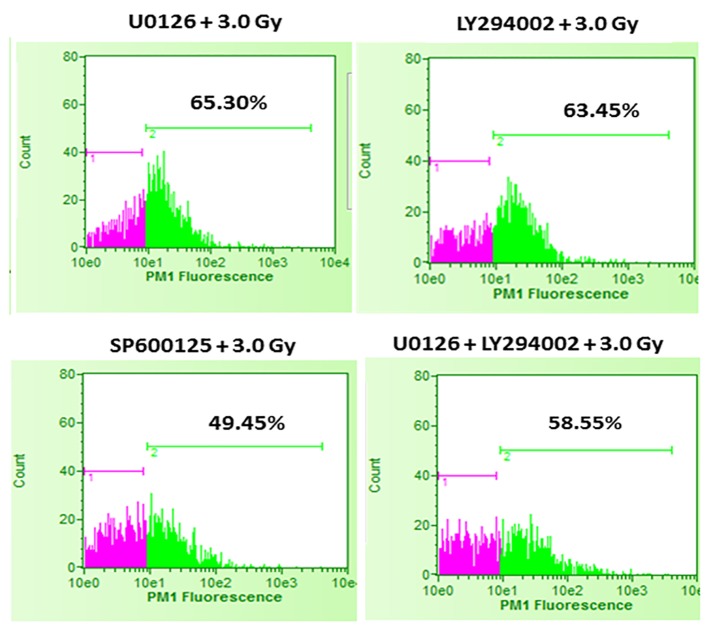

It was interesting to find that whether the equal increase in cell death in the presence of either U0126 or LY294002 is an arbitrary finding or has more significance. For this, in the next set of experiments, B16F10 cells were treated with either 20 µM U0126 or 20 µM LY294002, 24 h before exposing cells to 3.0 Gy of radiation. With 3.0 Gy, radiation alone treatment produced significant amount of cell death compared to control as well 2.0 Gy of radiation exposure (Fig. 2). Surprisingly, B16F10 cells pre-treated with either 20 µM U0126 or LY294002 prior to 3.0 Gy of radiation exposure showed almost equal increase in cell death (about 55%, Fig. 4) compared to 3.0 Gy group (Figs. 2 and 5). B16F10 cells pre-treated with 20 µM SP600125 prior to 3.0 Gy of radiation exposure also increased cell death compared to 3.0 Gy group (P < 0.01, Figs. 2 and 5). However, the total increase in cell death is low compared to enhancement in radiation-induced cell death induced by U0126 and LY294002. Above two sets of experiments indicate that inhibition of either ERK1/2 or AKT activation prior to 2.0 or 3.0 Gy of radiation moderately but equally sensitized B16F10 cells to radiation-induced cell death while inhibition of JNK enhanced radiation-induced cell death at relatively low level.

Figure 5.

Effect of inhibition of ERK1/2, AKT and JNK pathways prior to 3.0 Gy radiation exposures of B16F10 cells. B16F10 cells were treated with 20 µM concentrations of U0126, LY294002 and SP600125, 24 h before exposing cells to 3.0 Gy of radiation. Pink color indicates viable cell fraction and green color indicates dead cell fraction. Cell death in U0126 + 3.0 Gy group versus 3.0 Gy alone: P < 0.0001; cell death in LY294002 + 3.0 Gy group versus 3.0 Gy alone: P < 0.0001; cell death in SP600125 + 3.0 Gy group versus 3.0 Gy alone: P < 0.01; cell death in U0126 + LY29400 + 3.0 Gy versus 3.0 Gy alone: P < 0.0001.

Combined inhibition of ERK1/2 and AKT did not increase cell death compared to individual inhibition

From the above experiments, it is clear that inhibition of either ERK1/2 or AKT activity equally increases radiation-induced cell death. There is a possibility that combined inhibition of ERK1/2 and AKT activity could further enhance the radiation-induced cell death. To study this, B16F10 cells were treated with a combination of 20 µM each of U0126 and LY294002, 24 h before exposing cells to 2.0 Gy and 3.0 Gy radiation doses. Exposure of B16F10 cells treated with 20 µM U0126 and LY294002 to 2.0 Gy radiation resulted in significantly higher cell death compared to 2.0 Gy radiation alone treatment (Fig. 3). However, the amount of cell death is not significantly higher compared to the cell death induced by individual ERK1/2 or AKT inhibition (Fig. 4). Further, the similar trend was observed even at 3.0 Gy where, combined effect of ERK1/2 and AKT inhibition was not better than individual inhibition of either ERK1/2 or AKT (Figs. 4 and 5). This suggests that ERK1/2 and AKT possibly protect survival against radiation-induced cell death through common downstream molecule/s in B16F10 cells.

Discussion

Exposure of tumor cells to clinically relevant low doses of ionizing radiation causes DNA damage and the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). The generated ROS plays an important role in the biological effects induced by ionizing radiation. It is believed that ROS generation subsequently leads to rapid activation of EGFR-Ras pathway and its downstream molecules such as ERK1/2, AKT, etc. [4, 25-30]. Activated ERK1/2 and AKT pathways are well known to cause radiation resistance in Ras/Braf mutated tumor cells [2, 12-14, 16, 18]. The present study utilized a highly metastatic and radio-resistant [21, 23] B16F10 cells that carry wild-type Ras or Braf [20, 22, 24]. Exposure of B16F10 cells to 1.0 to 3.0 Gy of radiation significantly increased p-ERK1/2, p-AKT as well as p-JNK levels. Although B16F10 cells are without mutations in Braf, Kras or Nras, it is highly possible that mutations in Pdgfra (well known to activate ERK1/2) as well as Atm (well known to activate PI3K-AKT) are responsible for the constitutive expression of ERK1/2 and AKT in B16F10 cells [24], upon radiation exposure. Further, ERK1/2 is known to get activated by autocrine factors without mutations in Ras [31].

Activated ERK1/2 modulates the functions of several transcription factors, protein kinases, protein phosphatases, cytoskeletal proteins, signaling molecules, apoptosis-related proteins, as well as other types of proteins [32], while activated AKT modulates the function of numerous substrates involved in the regulation of cell survival, cell cycle progression and cellular growth [33, 34], whereas JNK acts as pro-apoptotic as well as anti-apoptotic depending on the conditions [35]. Interestingly, in B16F10 cells, it was observed that both ERK1/2 and AKT inhibition equally enhanced radiation-induced cell death, while inhibition of JNK did show radiation sensitization to a lesser amount. Further, the study showed that dual inhibition of ERK1/2 and AKT pathways failed to further increase cell death compared to inhibition of ERK1/2 or AKT pathways individually. Thus, it is assumed that ERK1/2 and AKT possibly provide protection against radiation-induced cell death through common downstream molecule/s.

Studies have shown that individually both ERK1/2 and AKT pathways activate multiple substrates leading to a wide range of effects on the cell [32, 36]. Additionally, ERK1/2 and AKT are known to cross talk with multiple substrates including several kinases, transcription factors, etc. which increase the complexity of the signaling network. For example, previous studies have shown that eukaryotic translation initiation factor (eIF4E) and cyclic AMP responsive element B (CREB) are known to be activated by radiation [37-40]. Further both molecules are known to be activated by ERK1/2 and AKT [41-44]. Several such molecules are expected to be cross talking in the network. It is required to evaluate them thoroughly in future studies. Overall the current study showed that even without activating mutations in Ras or Braf genes, ERK1/2 and AKT play a critical role in B16F10 cell survival upon radiation exposure and possibly act through common downstream effector/s.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by Board of Research in Nuclear Sciences (BRNS), India (BRNS/2013/34/8) to DU. BSK received financial assistance as Senior Research Fellowship (08/652/2017) from Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), India.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- 1.Friedman DA, Tait L, Vaughan AT. Influence of nuclear structure on the formation of radiation-induced lethal lesions. Int J Radiat Biol. 2016;92(5):229–240. doi: 10.3109/09553002.2016.1144941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Samid D, Miller AC, Rimoldi D, Gafner J, Clark EP. Increased radiation resistance in transformed and nontransformed cells with elevated ras proto-oncogene expression. Radiat Res. 1991;126(2):244–250. doi: 10.2307/3577825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldkorn T, Balaban N, Shannon M, Matsukuma K. EGF receptor phosphorylation is affected by ionizing radiation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1358(3):289–299. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4889(97)00063-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valerie K, Yacoub A, Hagan MP, Curiel DT, Fisher PB, Grant S, Dent P. Radiation-induced cell signaling: inside-out and outside-in. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6(3):789–801. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kidd AR 3rd, Snider JL, Martin TD, Graboski SF, Der CJ, Cox AD. Ras-related small GTPases RalA and RalB regulate cellular survival after ionizing radiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;78(1):205–212. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dent P, Yacoub A, Fisher PB, Hagan MP, Grant S. MAPK pathways in radiation responses. Oncogene. 2003;22(37):5885–5896. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yan Y, Hein AL, Greer PM, Wang Z, Kolb RH, Batra SK, Cowan KH. A novel function of HER2/Neu in the activation of G2/M checkpoint in response to gamma-irradiation. Oncogene. 2015;34(17):2215–2226. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abbott DW, Holt JT. Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 2 activation is essential for progression through the G2/M checkpoint arrest in cells exposed to ionizing radiation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(5):2732–2742. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.5.2732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yan Y, Black CP, Cowan KH. Irradiation-induced G2/M checkpoint response requires ERK1/2 activation. Oncogene. 2007;26(32):4689–4698. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hein AL, Ouellette MM, Yan Y. Radiation-induced signaling pathways that promote cancer cell survival (review) Int J Oncol. 2014;45(5):1813–1819. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2014.2614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Affolter A, Schmidtmann I, Mann WJ, Brieger J. Cancer-associated fibroblasts do not respond to combined irradiation and kinase inhibitor treatment. Oncol Rep. 2013;29(2):785–790. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.2180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carter S, Auer KL, Reardon DB, Birrer M, Fisher PB, Valerie K, Schmidt-Ullrich R. et al. Inhibition of the mitogen activated protein (MAP) kinase cascade potentiates cell killing by low dose ionizing radiation in A431 human squamous carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 1998;16(21):2787–2796. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chung EJ, Brown AP, Asano H, Mandler M, Burgan WE, Carter D, Camphausen K. et al. In vitro and in vivo radiosensitization with AZD6244 (ARRY-142886), an inhibitor of mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 kinase. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(9):3050–3057. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim IA, Bae SS, Fernandes A, Wu J, Muschel RJ, McKenna WG, Birnbaum MJ. et al. Selective inhibition of Ras, phosphoinositide 3 kinase, and Akt isoforms increases the radiosensitivity of human carcinoma cell lines. Cancer Res. 2005;65(17):7902–7910. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krasilnikov M, Adler V, Fuchs SY, Dong Z, Haimovitz-Friedman A, Herlyn M, Ronai Z. Contribution of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase to radiation resistance in human melanoma cells. Mol Carcinog. 1999;24(1):64–69. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2744(199901)24:1<64::AID-MC9>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marampon F, Gravina GL, Di Rocco A, Bonfili P, Di Staso M, Fardella C, Polidoro L. et al. MEK/ERK inhibitor U0126 increases the radiosensitivity of rhabdomyosarcoma cells in vitro and in vivo by downregulating growth and DNA repair signals. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10(1):159–168. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Affolter A, Fruth K, Brochhausen C, Schmidtmann I, Mann WJ, Brieger J. Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase extracellular signal-related kinase in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas after irradiation as part of a rescue mechanism. Head Neck. 2011;33(10):1448–1457. doi: 10.1002/hed.21623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xie Q, Zhou Y, Lan G, Yang L, Zheng W, Liang Y, Chen T. Sensitization of cancer cells to radiation by selenadiazole derivatives by regulation of ROS-mediated DNA damage and ERK and AKT pathways. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;449(1):88–93. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.04.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gupta AK, Bakanauskas VJ, Cerniglia GJ, Cheng Y, Bernhard EJ, Muschel RJ, McKenna WG. The Ras radiation resistance pathway. Cancer Res. 2001;61(10):4278–4282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Melnikova VO, Bolshakov SV, Walker C, Ananthaswamy HN. Genomic alterations in spontaneous and carcinogen-induced murine melanoma cell lines. Oncogene. 2004;23(13):2347–2356. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaliski A, Maggiorella L, Cengel KA, Mathe D, Rouffiac V, Opolon P, Lassau N. et al. Angiogenesis and tumor growth inhibition by a matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor targeting radiation-induced invasion. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4(11):1717–1728. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marone R, Erhart D, Mertz AC, Bohnacker T, Schnell C, Cmiljanovic V, Stauffer F. et al. Targeting melanoma with dual phosphoinositide 3-kinase/mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors. Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7(4):601–613. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang Q, Li F, Liu X, Li W, Shi W, Liu FF, O’Sullivan B. et al. Caspase 3-mediated stimulation of tumor cell repopulation during cancer radiotherapy. Nat Med. 2011;17(7):860–866. doi: 10.1038/nm.2385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Castle JC, Kreiter S, Diekmann J, Lower M, van de Roemer N, de Graaf J, Selmi A. et al. Exploiting the mutanome for tumor vaccination. Cancer Res. 2012;72(5):1081–1091. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amundson SA, Bittner M, Fornace AJ Jr. Functional genomics as a window on radiation stress signaling. Oncogene. 2003;22(37):5828–5833. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liang K, Ang KK, Milas L, Hunter N, Fan Z. The epidermal growth factor receptor mediates radioresistance. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;57(1):246–254. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(03)00511-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barzilai A, Yamamoto K. DNA damage responses to oxidative stress. DNA Repair (Amst) 2004;3(8-9):1109–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hammond EM, Giaccia AJ. The role of ATM and ATR in the cellular response to hypoxia and re-oxygenation. DNA Repair (Amst) 2004;3(8-9):1117–1122. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Astsaturov I, Cohen RB, Harari P. Targeting epidermal growth factor receptor signaling in the treatment of head and neck cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2006;6(9):1179–1193. doi: 10.1586/14737140.6.9.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Drigotas M, Affolter A, Mann WJ, Brieger J. Reactive oxygen species activation of MAPK pathway results in VEGF upregulation as an undesired irradiation response. J Oral Pathol Med. 2013;42(8):612–619. doi: 10.1111/jop.12056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Satyamoorthy K, Li G, Gerrero MR, Brose MS, Volpe P, Weber BL, Van Belle P. et al. Constitutive mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in melanoma is mediated by both BRAF mutations and autocrine growth factor stimulation. Cancer Res. 2003;63(4):756–759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoon S, Seger R. The extracellular signal-regulated kinase: multiple substrates regulate diverse cellular functions. Growth Factors. 2006;24(1):21–44. doi: 10.1080/02699050500284218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fresno Vara JA, Casado E, de Castro J, Cejas P, Belda-Iniesta C, Gonzalez-Baron M. PI3K/Akt signalling pathway and cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2004;30(2):193–204. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2003.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nitulescu GM, Margina D, Juzenas P, Peng Q, Olaru OT, Saloustros E, Fenga C. et al. Akt inhibitors in cancer treatment: The long journey from drug discovery to clinical use (Review) Int J Oncol. 2016;48(3):869–885. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2015.3306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu J, Lin A. Role of JNK activation in apoptosis: a double-edged sword. Cell Res. 2005;15(1):36–42. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carracedo A, Pandolfi PP. The PTEN-PI3K pathway: of feedbacks and cross-talks. Oncogene. 2008;27(41):5527–5541. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Amorino GP, Hamilton VM, Valerie K, Dent P, Lammering G, Schmidt-Ullrich RK. Epidermal growth factor receptor dependence of radiation-induced transcription factor activation in human breast carcinoma cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13(7):2233–2244. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-12-0572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cataldi A, Di Giacomo V, Rapino M, Zara S, Rana RA. Ionizing radiation induces apoptotic signal through protein kinase Cdelta (delta) and survival signal through Akt and cyclic-nucleotide response element-binding protein (CREB) in Jurkat T cells. Biol Bull. 2009;217(2):202–212. doi: 10.1086/BBLv217n2p202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hayman TJ, Williams ES, Jamal M, Shankavaram UT, Camphausen K, Tofilon PJ. Translation initiation factor eIF4E is a target for tumor cell radiosensitization. Cancer Res. 2012;72(9):2362–2372. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suarez CD, Deng X, Hu CD. Targeting CREB inhibits radiation-induced neuroendocrine differentiation and increases radiation-induced cell death in prostate cancer cells. Am J Cancer Res. 2014;4(6):850–861. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Du K, Montminy M. CREB is a regulatory target for the protein kinase Akt/PKB. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(49):32377–32379. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hay N, Sonenberg N. Upstream and downstream of mTOR. Genes Dev. 2004;18(16):1926–1945. doi: 10.1101/gad.1212704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Costes S, Broca C, Bertrand G, Lajoix AD, Bataille D, Bockaert J, Dalle S. ERK1/2 control phosphorylation and protein level of cAMP-responsive element-binding protein: a key role in glucose-mediated pancreatic beta-cell survival. Diabetes. 2006;55(8):2220–2230. doi: 10.2337/db05-1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shveygert M, Kaiser C, Bradrick SS, Gromeier M. Regulation of eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (eIF4E) phosphorylation by mitogen-activated protein kinase occurs through modulation of Mnk1-eIF4G interaction. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30(21):5160–5167. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00448-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]