Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is an aging-related, degenerative brain disease of adults. Most (~95%) of AD occurs sporadically and is associated with early-appearing deficits in brain regional glucose uptake, changes in cerebrospinal fluid AD-related proteins, regional brain atrophy and oxidative stress damage. We treated mild-moderate AD individuals with R(+)-pramipexole-dihydrochloride (R(+)PPX), a neuroprotective, lipophilic-cation, free-radical scavenger that accumulates into brain and mitochondria. 19 subjects took R(+)PPX twice a day in increasing daily doses up to 300 mg/day under a physician-sponsor IND (60,948, JPB), IRB-approved protocol and quarterly external safety committee monitoring. 15 persons finished and contributed baseline and post-treatment serum, lumbar spinal fluid, brain 18F-2DG PET scans and ADAS-Cog scores. ADAS-Cog scores did not change (n=1), improved (n=2), declined 1–3 points (n= 5) or declined 4–13 points (n=8) over 6 months of R(+)PPX treatment. Serum PPX levels were not related to changes in ADAS-Cog scores. Fasting AM serum PPX levels at 6 months varied considerably across subjects and correlated strongly with CSF [PPX] (r=0.97, p<0.0001). CSF [PPX] was not related to CSF [Aβ(42)], [Tau], or [P-Tau]. Regional 18F-2DG measures of brain glucose uptake demonstrated a 3–6% decline during R(+)PPX treatment. 56 mild-moderate adverse events occurred, 26 probably/definitely related to R(+)PPX use, with 4 withdrawals. R(+)PPX was generally well-tolerated and entered brain extracellular space linearly. Further studies of R(+)PPX in AD should include a detailed pharmacokinetic study of peak and trough serum [PPX] variations among subjects prior to planning any larger studies that would be needed to determine efficacy in altering disease progression.

Keywords: Alzheimer Disease, Investigational Treatment, Cognitive Disorder, PET Scan, Oxidative Stress, Biomarkers

INTRODUCTION

The aging of populations has produced a potential “grey tsunami” of demented persons that will soon overwhelm existing medical and socioeconomic systems that currently provide medical and respite care [1]. In the United States, approximately 5 million persons suffer from progressive dementia, at an annual cost of over 200 billion dollars [2]. The age-vulnerable population for dementia is predicted to increase 2–3 fold over the next 20–30 years, such that the costs of providing care for these persons will approach the level of the baseline budget for the Department of Defense. This is an unsustainable situation for the US and other comparable countries. Effective strategies to intervene in the progression of dementia for these persons is sorely needed.

The major cause of aging-related dementia is Alzheimer’s disease (AD), that in most demented persons results from a combination of neurodegeneration with loss of neuronal soma and synaptic functional impairment/loss combined variably with brain microvascular disease [3]. In AD there is progressive deposition of aggregated proteins such as Aβ(1–42) in extracellular spaces (“plaques”) and phosphorylated Tau in intraneuronal “tangles”. These easily visualized protein pathological markers have assumed historical primacy as etiologic factors for AD origin and progression, but these concepts have been and remain controversial [4].

It is likely that the majority of AD that occurs sporadically, not by autosomal inheritance, arises for heterogeneous reasons related to individual genetic risk factors and environment (ie, diet, toxins, etc) interacting with the neurobiology of aging and brain inflammation. If true, then it is unlikely that a single treatment will be helpful for all AD sufferers, in the same manner that cancer patients now commonly have specific therapies based on specific “driver” pathogenic gene mutations found in their tumors.

If AD is a heterogeneous and complex syndrome, and not a single disease, then therapies should target major pathogenic abnormalities that could vary across affected persons. In that context, abnormalities found to varying extents in AD persons and tissues include altered brain glucose metabolism [5], deficient mitochondrial respiration [6] and increased evidence of oxidative stress damage [7, 8]. Successful strategies for slowing AD clinical and pathological progression can address each of these problems separately, as a function of individual variations in their influence on that person’s brain disease.

R(+) pramipexole (PPX) is the D2-family dopamine receptor-inactive enantiomer of S(−) PPX, a potent D2-family dopamine receptor agonist used to treat dopamine deficiency-derived motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease [9, 10]. R(+)PPX and S(−)PPX differ by at least 100-fold in in vitro affinity for D2-family dopamine receptors [11]. R(+)PPX accumulates into brain and mitochondria [12], scavenges a variety of oxidative and nitrative free radicals [12], and demonstrates neuroprotection in vitro and in vivo against mitochondrial and oxidative insults [13]. R(+)PPX taken p.o. at 300 mg/day does not suppress prolactin levels as do typical D2-family dopamine receptor agonists [14]. R(+)PPX has been tested clinically in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS, Lou Gherig’s disease in US; motor neuron disease in Europe) where it showed significant effects on a metric combining slowing of disease progression and prolonging of survival in a Phase II study [15] and in a clinically-defined subgroup of patients in a larger Phase III study [16]. R(+)PPX is relatively free of toxicity, with reversible lowering of WBC count observed in a small percentage of subjects [15–17].

The current study was a single-arm safety and tolerability study of 6 months of R(+)PPX in subjects with mild-moderate AD symptoms (n=20). Although this was designed to primarily be a safety and tolerability study, we also examined cognitive performance, FDG PET and a variety of serum and CSF biomarkers before and after the 6 months of PPX treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Screening and Enrollment

We enrolled a total of 20 subjects into the study. A total of 22 subjects were screened. Twenty qualified for the study and were enrolled while 2 did not meet entry criteria. One of the 20 enrolled subjects withdrew after completing the screening visit but before beginning any baseline measures due to concerns about study burden. Thus, a total of 19 individuals (mean [s.d] age of 70.2 [7.9] years, 42.1% [n=8] female, and mean MMSE of 21.5 [4.0]) were dosed with R(+)-PPX. Of the 19 subjects who enrolled and received study drug, 15 completed all visits as 4 subjects withdrew due to adverse events (AEs).

Inclusion:Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion:Exclusion criteria for this study were as follows:

| Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria at Entry | |

|---|---|

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|

|

Study Conduct

All aspects of the study were approved and monitored by the University of Kansas IRB. All subjects provided informed consent to participate and signed an IRB-approved consent form. The clinical study took place at the Alzheimer’s Center at the University of Kansas, where all enrollment and testing took place and Dr. J. Burns served as local PI and medical monitor. R(+)PPX is an experimental drug and was administered to AD subjects under the auspices of a physician-sponsor IND (60,948) held by Dr. J. Bennett, who had no involvement in subject recruitment or treatment. An independent external data and safety monitoring board (DSMB) composed of three investigational neurologists reviewed quarterly all safety data from blood draws and clinical reports.

Dosing with R(+) pramipexole

R(+) PPX.2HCl was prepared and purified under GMP conditions by Quality Chemical Laboratories (QCL, Wilmington, NC). Analyses revealed chemical purity >99.9% and enantiomeric purity ≥99.5%. Drug was packaged in 10-gram aliquots in sealed vials and delivered to Kansas University Medical Center Investigational Pharmacy where it was compounded in water at 10 mg/ml concentration and stored at 4 degrees. Independent analyses by QCL showed drug stability in water solution at 4 degrees of at least 2 months.

After providing informed consent, subjects were dosed with R(+)PPX solution at 50 mg (5 ml) bid for one month, 100 mg (10 ml) bid for one month and 150 mg (15 ml) bid for up to 4 months. Subjects were allowed to continue existing dementia medications providing they had been on a stable dose for at least 30 days.

Collection and analyses of serum and CSF samples

Prior to starting R(+)PPX therapy, all subjects underwent collection of serum and seated lumbar CSF samples, both of which were coded and stored at −80 degrees. The subjects who were able to reach 300 mg/day (n=14) or 200 mg/day (n=1) took an evening dose of R(+)PPX between ~6–9PM, then underwent fasting and overnight drug withdrawal. In the following morning they had blood for serum and seated lumbar CSF samples taken. Their period of R(+)PPX withdrawal was not controlled and ranged from ~12–15 hours. Aliquots on dry ice were sent to Dr. J. Bennett for analyses of eicosanoids, cytokines, AD-related proteins and PPX levels. Eicosonoids were assayed by LC-MS/MS in the VCU Lipidomics Core laboratory (Dr. R. Chalfant, Director). Cytokines and AD-related proteins were assayed by ELISA. PPX levels were assayed by LC-MS/MS at AMRI Global, LLC.

Safety monitoring

All subjects had regular clinic visits and monthly or bimonthly blood draws taken for complete blood counts. These results were reported to the DSMB quarterly.

18F-2DG PET scans

Participants had FDG PET imaging obtained before beginning the intervention and after 6 months of R(+)PPX. PET images were obtained on a GE Discovery ST-16 PET/CT. All pre- and post-intervention FDG-PET scan images were analyzed in SPM8. The images were centered with the origin at the anterior commissure and then co-registered using normalized mutual information. Image voxels were standardized to the mean cerebellar region of interest (ROI) as cerebellar metabolism is relatively well preserved in AD. This was done to avoid artificial inflation of FDG uptake values, which is common when scaling to a global mean in the presence of a pathological condition.

RESULTS

Cognitive Scores

Table 1 shows the distribution of ADAS-Cog scores obtained at all visits. Subjects had variable baseline scores (range 9–37) and responses to R(+)PPX treatment: one had no change (01), two had reductions (improvements; ID 06, 12), five had decline (worsening) of 1–3 points (ID 03, 14, 15, 17, 21) and eight had decline of 4–13 points (ID 02, 07, 09, 13, 16, 19, 20, 22).

Table 1.

ADAS-Cog Scores Per Subject

| Study ID | Baseline Cog | V2 Cog | V3 Cog | V4 Cog | Change (V4-BL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| 01 | 20 | - | 12 | 20 | 0 |

|

| |||||

| 02 | 9 | - | 11 | 15 | 6 |

|

| |||||

| 03 | 14 | - | 17 | 15 | 1 |

|

| |||||

| 06 | 27 | 24 | 24 | 26 | −1 |

|

| |||||

| 07 | 17 | 12 | 18 | 21 | 4 |

|

| |||||

| 09 | 15 | 14 | 24 | 20 | 5 |

|

| |||||

| 12 | 24 | 29 | 22 | 20 | −4 |

|

| |||||

| 13 | 14 | 18 | 20 | 20 | 6 |

|

| |||||

| 14 | 28 | 32 | 33 | 31 | 3 |

|

| |||||

| 15 | 14 | 21 | 17 | 17 | 3 |

|

| |||||

| 16 | 37 | 46 | 39 | 44 | 7 |

|

| |||||

| 17 | 17 | 23 | 18 | 18 | 1 |

|

| |||||

| 19 | 17 | 19 | 20 | 24 | 7 |

|

| |||||

| 20 | 29 | 36 | 42 | - | 13 |

|

| |||||

| 21 | 31 | 29 | 26 | 33 | 2 |

|

| |||||

| 22 | 10 | 8 | 13 | 17 | 7 |

|

| |||||

| Mean(LOCF) | 20.2 | 22.1 | 22.3 | 23.9 | +3.8 |

| s.d | 8.2 | 10.5 | 9.0 | 7.9 | 4.0 |

Data for the 16 subjects with 2 or more complete visits. Lower scores indicate better performance for ADAS-Cog.

LOCF= Last observation carried forward for missing data.

Effects of R(+)PPX on CSF biomarkers for AD

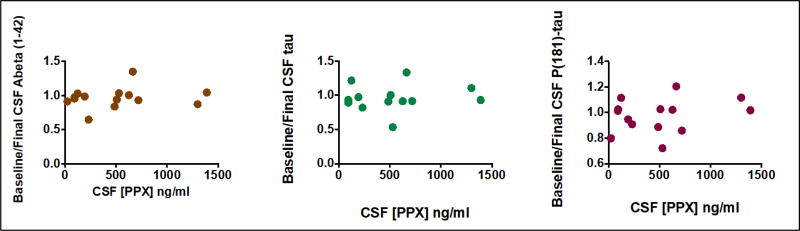

Figure 1 shows there was no apparent relationship among CSF [PPX] and baseline/final ratio of protein biomarkers associated with AD, such as [Aβ42], [Tau], or [phospho-Tau], all assayed with specific ELISA’s (Innotest®).

Figure 1.

CSF [PPX] does not predict baseline/final ratios of CSF Aβ42, Tau or P(181)-Tau.

Effects of R(+)PPX on brain regional glucose uptake

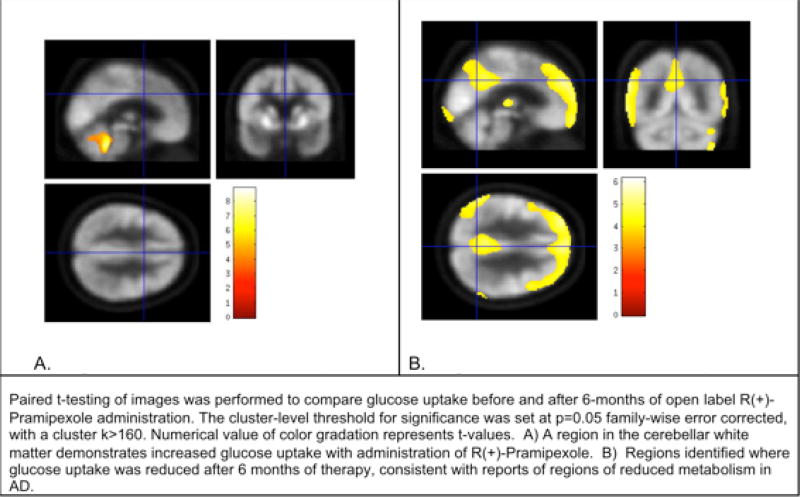

To assess changes in glucose uptake before and after the 6-months of R(+)-PPX open-label intervention, we conducted paired t-test comparison of the baseline and 6-month images (cluster-level threshold for significance p=0.05 family-wise error corrected, with a cluster k>160). One region in the cerebellar white matter demonstrated increased glucose uptake after the intervention. Broad regions were identified where glucose uptake decreased from pre- to post-intervention, suggesting a relative decrease in metabolism in these regions, consistent with regions of reduced metabolism in individuals with AD. Supplemental Table 2 shows the regional, cerebellum-normalized glucose uptake at baseline and after R(+)PPX treatment. Figure 2 shows visually the regional changes in glucose uptake.

Figure 2.

Representative images of brain regional FDG-PET signals that increased (left) and decreased (right) during 6 months of R(+) PPX treatment.

Unanticipated Potential Benefit

Two subjects had a history of Restless Leg Syndrome (RLS) symptoms: subject 19 had intermittent symptoms since approximately 1990 although never received a formal diagnosis and subject 22 was diagnosed in 2005. Both ceased experiencing these symptoms after initiating study drug dosing. Subject 22 had attempted Mirapex dosing in the past for RLS but was unable to tolerate its use due to side effects; these side effects were not experienced during this trial.

Drug Compliance and Pharmacokinetics

Drug compliance was monitored at study visits (every two months). Subjects (and their study partner) were asked to bring remaining study drug and any empty containers (if applicable) with them to study visits. Remaining study drug was measured and all returned containers were taken to our Investigational Pharmacy for disposal. Drug compliance percentage was calculated by comparing the actual volume of drug used with the expected volume of drug used based on dosing regimen and time between visits. Calculated compliance percentage was determined for the entire study. Calculated compliance over the final last 2 months of the study was also calculated as behaviors affecting compliance changed in some cases over the course of the study. The latter compliance calculation is most relevant to outcomes as this is the period where the dosing regimen was highest and the dose was sustained the longest.

The recorded amount of drug remaining was influenced by a number of factors including: errors in dose measurement, drug lost due to accidents, and failure to return used containers. Additionally, in 2 subjects (ID 06 and 07) a pharmacy error led to dispensing of a diluted concentration of the drug for the first two months such that the subjects received about half the target dose.

This assessment of compliance suggests that most subjects were compliant with a mean compliance of 93.3% over the course of the study and 84.8% during the last two months (Table 2).

Table 2.

End of Intervention Serum and Cerebral Spinal Fluid (CSF) Drug Concentrations and Drug Compliance

|

Study ID |

Compliance % (entire study) |

Compliance % (last 2 months) |

Serum Concentration (ng/mL) |

CSF Concentration (ng/mL) |

Ratio Serum:CSF Concentration (Serum/CSF) |

Final dosage (mg/day) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | 90.7 | 90.3 | 1240 | - | - | 300 |

| 02 | 90.5 | 90.0 | 1380 | 1390 | 0.99 | 300 |

| 03 | 85.2 | 6.8 | 150 | 124 | 1.21 | 300 |

| 06 | 59.5 | 55.3 | 560 | 529 | 1.06 | 300 |

| 07 | 93.5 | 66.7 | 13 | 23 | 0.57 | 300 |

| 09 | 103.8 | 84.8 | 72 | 92 | 0.78 | 300 |

| 12 | 85.1 | 86.7 | 695 | 508 | 1.37 | 300 |

| 13 | 72.0 | 119.4 | 704 | 664 | 1.06 | 300 |

| 14 | 117.1 | ϕ | 424 | 486 | 0.87 | 200 |

| 15 | 95.6 | 90.9 | 160 | 192 | 0.83 | 300 |

| 16 | 100.0 | 99.0 | 441 | 719 | 0.61 | 300 |

| 17 | ϕ | ϕ | 1290 | 1300 | 0.99 | 300 |

| 19 | 114.0 | 98.68 | 254 | 231 | 1.10 | 300 |

| 21 | ϕ | 109.8 | 72 | 94 | 0.77 | 300 |

| 22 | 101.3 | 102.9 | 661 | 626 | 1.06 | 300 |

| Means | 92.9 | 84.7 | 541 | 498 | 0.95 |

Unable to estimate given one or more containers with drug remaining not returned

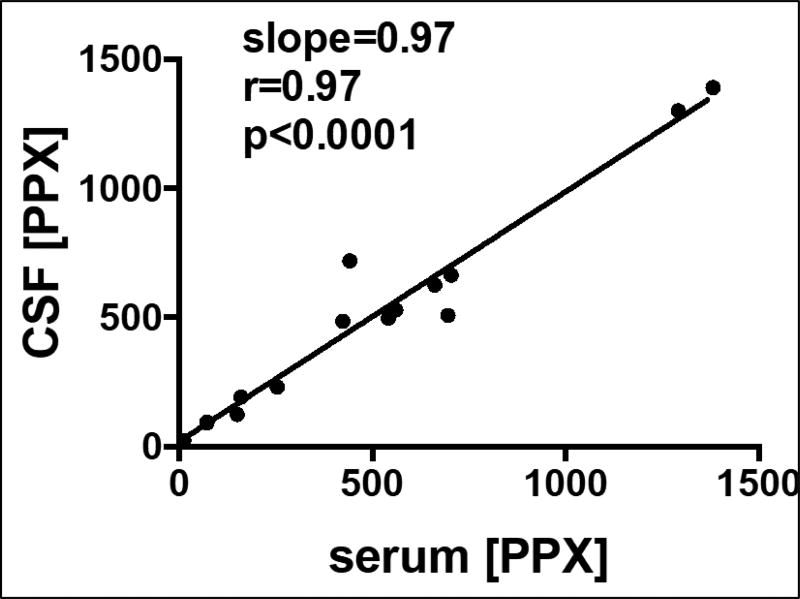

R(+)-Pramipexole concentration was assayed in serum and cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) samples by AMRI Global, LLC. CSF was collected after an overnight fast and was followed immediately by the blood draw for serum. Subjects were instructed to take their evening dose the night before; all CSF collections were estimated to be within 12–15 hours following last dose of study drug based on subjects/study partners reporting that evening doses were generally taken between 6 and 9 PM (generally with dinner or just prior to going to bed). Thus, the serum and CSF PPX levels represent drug remaining after ~2 half-lives, but individual drug clearances were not determined for each subject. Pre- and post-intervention lumbar punctures were successful 14 of the 15 subjects who completed the intervention. Baseline values of R(+)-Pramipxole in CSF and serum were below the quantitation limit (LLOQ 0.5ng/mL) with mean levels of 541 ng/ml in serum and 498 ng/ml in CSF at end of intervention (Table 2). 14/15 subjects reached the final target dose (300 mg/day); one subject tolerated on 200 mg/day (Table 2). Figure 3 shows that there was a strong linear relationship between serum and CSF [PPX], indicating that PPX crossed the blood-brain barrier in humans. Because no brain tissue was assayed for [PPX], it is unknown whether PPX accumulates into human brain as it does ~6-fold into mouse brain.

Figure 3.

Relationships among lumbar CSF levels of PPX and serum levels of PPX, both in ng/ml.

Adverse Events (AEs)

There were a total of 56 AEs reported in 18 subjects. All AEs were considered mild or moderate and none were serious or severe. Thirty-two (57%) of the AE’s were determined to be either “possibly” or “probably” related to the study medication. All study drug related AEs (Table 3) reported by the 15 subjects who completed all study visits either resolved while still on study medication or resolved by the End of Study visit, two weeks following last dose of study medication.

Table 3.

AEs Related to Study Drug or Affecting Dosing

| Possibly or Probably Related to Study Drug |

AEs related to Dose-Adjustments (n) |

AEs related to Discontinuation (n) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep disturbance | 8 | 6 | 2 |

| Increased confusion | 4 | 4 | 1 |

| Hallucinations | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Increased libido* | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Nausea | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Agitation/Irritability* | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Dizziness* | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Somnolence | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Confabulations | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Urticaria* | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Ankle swelling* | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Falls* | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Weight loss | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Decreased appetite | 1 | 0 | 0 |

Twenty-seven AEs led to dose adjustments (temporary or permanent) in 10 subjects (see Table 3). Six of the 10 subjects were returned to normal dosing. Four of those 6 achieved the target dose (300mg/day), while 1 was maintained at the intermediate dose (200mg/day) after AEs returned, and 1 withdrew due to AEs.

Of the 27 AEs that led to dose adjustments, all but one were considered possibly/probably related to the study drug. Nineteen of the 26 AEs that were possibly/probably related to study drug were identified in either the consent form or investigator’s brochure. Four subjects withdrew permanently from the study due to 10 AEs; four of these AEs were not listed in the consent form: urticaria, increased libido, irritability, and ankle swelling. The Investigator’s Brochure, however, has one report of urticaria related to (R)-PPX. Irritability, as a cause for discontinuation, occurred in 2 subjects.

We have also noted that the following symptoms occurred concurrently in 3 subjects when dosing was increased: increased confusion, agitation, sleep disturbances, and hallucinations.

Safety Labs

Safety labs and adverse event reports were sent to an independent Data Safety and Monitoring Board (DSMB) at regular intervals. The DSMB determined the study was safe to continue in each of their reports, but did recommend checking white blood cell counts (WBC) at monthly intervals based on an article published in Nature Medicine in November, 2011. This study cited 5 of 97 subjects in a clinical trial of R(+) Pramipexole in subjects with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis had a lowering of their white blood cell counts, specifically neutrophils. Based on that relevant new information about the study medication, we amended our protocol in February 2012 to check white blood cell counts on a monthly rather than bi-monthly basis and to add an exclusion criterion of a minimum acceptable level of absolute neutrophils. Following the DSMB report in January 2013 the 3 additional WBC checks were removed as DSMB review of safety data up to that point did not show a trend of neutropenia. Continuing submissions to the DSMB included WBC and absolute neutrophil count data on all subjects at bi-monthly visits so they could continue to monitor those specific values.

Eight of the 20 subjects enrolled in the study had WBC counts at one or more visits outside of the normal reference range (all below the reference range); however, none of the these were determined to be clinically significant by the site PI and the subjects experienced no clinically significant signs or symptoms. Three of the 20 subjects had absolute neutrophil counts at a single timepoint that fell outside of the normal reference range (2 above and 1 below the reference range). None were determined to be clinically significant or associated with any clinically significant signs or symptoms. None of the subjects with WBC counts or absolute neutrophil counts outside of the normal reference range were subjects who withdrew from the study due to AEs.

There were 4 instances of clinically significant abnormal safety laboratory results in two subjects who remained asymptomatic. This included two possible urinary tract infections, a low platelet count, and mild anemia. After referral of the lab results to the subjects’ primary care physician, no interventions occurred.

Discussion

In the present study we treated 19 subjects who had mild-moderate AD with the novel mitochondrially-based neuroprotective drug R(+)PPX in a dose-ascension, open-label protocol. In this early Phase study, R(+)PPX was generally well tolerated up to daily doses of 300 mg/day (150 mg bid; 14/15 subjects). Four subjects left the study due to adverse events that may reflect residual D2 dopamine-receptor activity of R(+)PPX. No clinically significant hematological adverse events occurred. R(+)PPX appeared to cross the blood-brain barrier, with a demonstrated linear relationship among serum and CSF levels of [PPX].

The rationale for use of R(+)PPX in this study relates to its tolerability at high daily doses and lack of suppression of prolactin [14]; concentration into brain and mitochondria, combined with its ability to scavenge multiple oxidative and nitrative free radical species [12] ; its neuroprotective properties [12, 13]; and evidence for mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress damage in AD brain [6, 8].

In this small, single-arm, open-label study, there was no apparent effect of PPX on CSF levels of AD-related proteins, brain regional glucose uptake or cognition (ADAS-Cog), although the study was not powered or designed to demonstrate efficacy. The current study was also of limited duration (6 months maximum), and longer periods of drug treatment may be needed to find changes in AD biomarkers compared to a pre-treatment population.

We noted major variations in fasting AM serum PPX levels that may reflect differences in PPX clearance rates across individuals. Because our protocol did not formally assess pharmacokinetics of PPX in the AD subjects, we cannot provide an explanation for the variability of serum PPX levels observed. We did find that R(+)PPX appeared to enter the CSF space well, with CSF [PPX] approximating serum [PPX]. In mice R(+)PPX is concentrated into whole brain ~6-fold from plasma [12]. Because we did not assay any brain tissues from the subjects we cannot speculate as to whether R(+)PPX is concentrated into human brain like it is in mice.

Our findings in this small, open-label study in mild-moderate AD suggests that R(+)PPX is safe and well-tolerated. Larger controlled trials designed to study efficacy would be needed to test whether PPX impacts clinical AD progression, and more detailed pharmacokinetic studies would be desirable before such efficacy studies are undertaken.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was primarily supported by a grant to J. Bennett from the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation (ADDF). Additional support was provided by the MCV Foundation for the VCU Parkinson’s Center (J. Bennett) and several grants from the NIH to KUMC (J. Burns, PI). J. Bennett is the inventor for uses of R(+)PPX in neurodegenerative diseases and has personal financial interests in the commercial development of R(+)PPX. He played no role in subject selection, recruitment or treatment and remains blinded to identity of individual subjects. We thank Dr. Eric Vidoni for assistance in obtaining and analyzing 18F-2DG brain PET scans, and Drs. M. Mouradian, G. F. Wooten and U. Kang who served on the DSMB. JBennett participated in design of the study, holds the IND for R(+) pramipexole, performed all the ELISA’s on serum and CSF and wrote the manuscript. JBurns, PW and RB carried out the clinical study (subject recruitment, treatment, serum/CSF sampling, PET scans). All authors have reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Wortmann M. Dementia: a global health priority - highlights from an ADI and World Health Organization report. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2012;4:40. doi: 10.1186/alzrt143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hurd MD, Martorell P, Delavande A, Mullen KJ, Langa KM. Monetary costs of dementia in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1326–1334. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1204629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thal DR, Grinberg LT, Attems J. Vascular dementia: different forms of vessel disorders contribute to the development of dementia in the elderly brain. Exp Gerontol. 2012;47:816–824. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2012.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armstrong RA. The pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease: a reevaluation of the "amyloid cascade hypothesis". Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;2011:630865. doi: 10.4061/2011/630865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaffer JL, Petrella JR, Sheldon FC, Choudhury KR, Calhoun VD, Coleman RE, Doraiswamy PM. Predicting cognitive decline in subjects at risk for Alzheimer disease by using combined cerebrospinal fluid, MR imaging, and PET biomarkers. Radiology. 2013;266:583–591. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12120010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Young-Collier KJ, McArdle M, Bennett JP. The dying of the light: mitochondrial failure in Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;28:771–781. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-111487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonda DJ, Wang X, Lee HG, Smith MA, Perry G, Zhu X. Neuronal failure in Alzheimer's disease: a view through the oxidative stress looking-glass. Neurosci Bull. 2014;30:243–252. doi: 10.1007/s12264-013-1424-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang X, Wang W, Li L, Perry G, Lee HG, Zhu X. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1842:1240–1247. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Piercey MF. Pharmacology of pramipexole, a dopamine D3-preferring agonist useful in treating Parkinson's disease. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1998;21:141–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bennett JP, Jr, Piercey MF. Pramipexole--a new dopamine agonist for the treatment of Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Sci. 1999;163:25–31. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(98)00307-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wong SK. A 384-well cell-based phospho-ERK assay for dopamine D2 and D3 receptors. Anal Biochem. 2004;333:265–272. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Danzeisen R, Schwalenstoecker B, Gillardon F, Buerger E, Krzykalla V, Klinder K, Schild L, Hengerer B, Ludolph AC, Dorner-Ciossek C, Kussmaul L. Targeted antioxidative and neuroprotective properties of the dopamine agonist pramipexole and its nondopaminergic enantiomer SND919CL2x [(+)2-amino-4,5,6,7-tetrahydro-6-Lpropylamino-benzathiazole dihydrochloride] J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;316:189–199. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.092312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abramova NA, Cassarino DS, Khan SM, Painter TW, Bennett JP., Jr Inhibition by R(+) or S(−) pramipexole of caspase activation and cell death induced by methylpyridinium ion or beta amyloid peptide in SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma. J Neurosci Res. 2002;67:494–500. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang H, Larriviere KS, Keller KE, Ware KA, Burns TM, Conaway MA, Lacomis D, Pattee GL, Phillips LH, 2nd, Solenski NJ, Zivkovic SA, Bennett JP., Jr R+ pramipexole as a mitochondrially focused neuroprotectant: initial early phase studies in ALS. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2008;9:50–58. doi: 10.1080/17482960701791234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cudkowicz M, Bozik ME, Ingersoll EW, Miller R, Mitsumoto H, Shefner J, Moore DH, Schoenfeld D, Mather JL, Archibald D, Sullivan M, Amburgey C, Moritz J, Gribkoff VK. The effects of dexpramipexole (KNS-760704) in individuals with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat Med. 2011;17:1652–1656. doi: 10.1038/nm.2579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bozik ME, Mitsumoto H, Brooks BR, Rudnicki SA, Moore DH, Zhang B, Ludolph A, Cudkowicz ME, van den Berg LH, Mather J, Petzinger T, Jr, Archibald D. A post hoc analysis of subgroup outcomes and creatinine in the phase III clinical trial (EMPOWER) of dexpramipexole in ALS. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2014;15:406–413. doi: 10.3109/21678421.2014.943672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bozik ME, Mather JL, Kramer WG, Gribkoff VK, Ingersoll EW. Safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of KNS-760704 (dexpramipexole) in healthy adult subjects. J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;51:1177–1185. doi: 10.1177/0091270010379412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.