Abstract

Background

Training of birth attendants in neonatal resuscitation is likely to reduce birth asphyxia and neonatal mortality. We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the impact of neonatal resuscitation training (NRT) programme in reducing stillbirths, neonatal mortality, and perinatal mortality

Methods

We considered studies where any NRT was provided to healthcare personnel involved in delivery process and handling of newborns. We searched MEDLINE, CENTRAL, ERIC and other electronic databases. We also searched ongoing trials and bibliographies of the retrieved articles, and contacted experts for unpublished work. We undertook screening of studies and assessment of risk of bias in duplicates. We performed review according to Cochrane Handbook. We assessed the quality of evidence using the GRADE approach.

Results

We included 20 trials with 1 653 805 births in this meta-analysis. The meta-analysis of NRT versus control shows that NRT decreases the risk of all stillbirths by 21% (RR 0.79, 95% CI 0.44 to 1.41), 7-day neonatal mortality by 47% (RR 0.53, 95% CI 0.38 to 0.73), 28-day neonatal mortality by 50% (RR 0.50, 95% CI 0.37 to 0.68) and perinatal mortality by 37% (RR 0.63, 95% CI 0.42 to 0.94). The meta-analysis of pre-NRT versus post-NRT showed that post-NRT decreased the risk of all stillbirths by 12% (RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.83 to 0.94), fresh stillbirths by 26% (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.61 to 0.90), 1-day neonatal mortality by 42% (RR 0.58, 95% CI 0.42 to 0.82), 7-day neonatal mortality by 18% (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.73 to 0.93), 28-day neonatal mortality by 14% (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.13) and perinatal mortality by 18% (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.74 to 0.91).

Conclusions

Findings of this review show that implementation of NRT improves neonatal and perinatal mortality. Further good quality randomised controlled trials addressing the role of NRT for improving neonatal and perinatal outcomes may be warranted.

Trial registration number

PROSPERO 2016:CRD42016043668

Keywords: health services research, mortality, multidisciplinary team-care

What is already known?

A quarter of global neonatal deaths are due to birth asphyxia. The majority of these deaths occur in low-resource settings and are preventable.

Neonatal resuscitation training (NRT) of birth attendants using mannequins result in improved knowledge and skills needed for resuscitation.

Translation of NRT into improved neonatal outcomes and the effect estimates of improvements need to be re-evaluated and updated.

What this study adds?

This meta-analysis assessed the impact of NRT on stillbirths, 1-day neonatal mortality, 7-day neonatal mortality, 28-day neonatal mortality and perinatal mortality.

NRT resulted in significant reduction in stillbirths and early neonatal mortality. However, continuum of care is needed for mortality reduction from day 7 to 28.

Future studies also need to establish the best combination of settings, trainee characteristics and training frequency to sustain the existing effect on perinatal mortality reduction.

Introduction

Approximately a quarter of f million neonatal deaths worldwide are as a result of birth asphyxia.1 A large majority of these deaths occur in low-resource settings and are preventable. Approximately 5%–10% of newborns require some support to adapt to the extrauterine environment and to establish regular respiration.1 2 Simple resuscitative measures are often enough to resuscitate newborns that may even appear to be lifeless at birth. Studies have shown that essential newborn care has been effective in reducing stillbirths (SB).3

In developing countries, measures to improve resuscitative efforts through training of basic steps of neonatal resuscitation are expected to reduce birth asphyxia and neonatal mortality. Numerous studies have suggested that imparting neonatal resuscitation training (NRT) to healthcare providers involved in delivery process and handling of newborns has the potential to save newborn lives in low-income and middle-income settings4–10

Improvements in knowledge and skills of trainees following training programme in resource-limited settings have been reviewed. However, the impact on perinatal mortality outcomes has not been updated in last 5 years.9 The effect estimates of mortality reduction as a result of training of healthcare providers involved in delivery process and handling of newborns needs to be updated to inform hospital administrators and policy-makers the importance of investing in NRT to sustain and improve neonatal survival. A previous systematic review and meta-analysis11 assessed knowledge, skills, neonatal morbidity, neonatal mortality in first 7 days after birth and from day 8 to 28. However, it did not include outcomes of stlillbirth, 1-day neonatal mortality or perinatal mortality which has been included in our review.

The objective of this review is to assess the impact of NRT programme in reducing stillbirths, 1-day neonatal mortality, 7-day neonatal mortality, 28-day neonatal mortality and perinatal mortality.

Materials and methods

Inclusion criteria

Types of studies

We included relevant randomised, quasi-randomised controlled trials, interrupted time series studies and before–after studies regardless of language or publication status.

Types of participants (population) trained

We considered studies where NRT was provided to healthcare providers (including neonatologists, physicians, nurses, interns, midwives, traditional/community birth attendants, auxillary nurse midwives, village health workers, paramedics) involved in delivery process and handling of newborns in a community (home-based, rural and village clusters) or a hospital (including district hospitals, health centres, dispensaries, teaching/university hospitals, regional hospital, delivery/health centres, local hospitals and tertiary care hospital) setting.

Types of interventions and comparison

Studies in which any NRT was compared with a control group (that received no NRT) or compared with data before the study (pre-NRT vs post-NRT) were included. For this purpose, we considered any NRT programme of healthcare professionals, including the American Academy of Pediatrics’ (AAP) Neonatal Resuscitation Program (NRP), Helping Babies Breathe (HBB) or any other training programme that had NRP or HBB as a clearly mentioned component of training methodology.

Types of outcomes measures

We included following outcomes in the review:

Stillbirths: defined as number of deaths prior to complete expulsion or extraction of products of conception from its mother.

Fresh stillbirth: clinically defined as those deaths with no signs of life at any time after birth and without any signs of maceration.

1-day neonatal mortality: defined as number of deaths in first 24 hours of life

7-day neonatal mortality: defined as number of deaths in first 7 days of life

Perinatal mortality: defined as number of stillbirths and deaths in the first week of life.

28-day neonatal mortality: defined as number of deaths in the first 28 days of life.

Search strategy

We searched following electronic databases from inception to July 2016: MEDLINE (PubMed), The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, The Cochrane Library); Education Resources Information Centre (ERIC), Web of Science, Science Citation Index and Scientific Electronic Library Online. The search strategies for PubMed and CENTRAL can be found in supplementary files S1 and S2 respectively. We also searched for ongoing trials at www.clinicaltrials.gov and www.controlled-trials.com. We searched published abstracts of conferences and examined bibliographies of retrieved articles for additional studies. We contacted and requested experts and authors in this field to provide possible unpublished work.

Study selection and data extraction

Screening of studies

Two reviewers (MNK and AB) independently examined studies identified by literature search; discarded articles that did not fulfil the inclusion criteria and assessed full texts of all relevant articles for inclusion. A third reviewer (AP) resolved disagreement among the primary reviewers.

Data extraction and management

For all studies that fulfilled the inclusion criteria, two reviewers (KK, SB) extracted data (table 1 and 2). Third review author (AP) cross-checked the data and resolved discrepancies. For studies where required data was lacking or could not be calculated, we requested the corresponding author for details.

Table 1.

Characteristic of included studies

| Sr. No. | Author | Country | Study design | Study period | Funding |

| 1 | Bang et al20 | India | RCT | 36 months (1995–1998) |

|

| 2 | Ariawan et al* 8 | Indonesia | Pre–Post training | NR | NR |

| 3 | Carlo et al17** | Argentina, Democratic Republic of Congo, Guatemala, India, Pakistan and Zambia | Pre–Post training and RCT | 42 months (ENC: Mar 2005 and Feb 2007; NRP: Jul 2006–Aug 2008) |

|

| 4 | Carlo et al 18 | Argentina, Democratic Republic of Congo, Guatemala, India, Pakistan and Zambia | Pre–Post training and RCT | 42 months (ENC: Mar 2005 and Feb 2007; NRP: Jul 2006–Aug 2008) |

|

| 5 | Gill et al21 | Zambia | Prospective, cluster randomised and controlled effectiveness study | 30 months (Jun 2006–Nov 2008) |

|

| 6 | Zhu et al26 | China | Perspective study, pre–post training (traditional resuscitation vs NRPG) | 24 months (1993–1995) | NR |

| 7 | Deorari et al24 | India | Pre–post training ( | NR |

|

| 8 | Jeffery et al28 | Macedonia | Pre–Post training | 60 months (1997–2001) |

|

| 9 | Vakrilova et al30 | Bulgeria | Pre–Post training ( | 48 months (2000–2003) |

NR |

| 10 | O’Hare et al25 | Uganda | Pre–Post training (historic group vs NRP pilot) | 1 month (Dec 2001–Jan 2002) |

|

| 11 | Opiyo et al19 | Kenya | Pre–Post training | NR |

|

| 12 | Boo31 | Malaysia | Pre–Post training, prospective observational study | 100 months (Sep 1996–Dec 2004) |

|

| 13 | Sorensen et al29 | Tanzania | Prospective study, Pre–Post training | 14 weeks (Jul 2008–Nov 2008) |

|

| 14 | Hole et al32 | Malawi, Africa | Pre–Post training | 30 months (Jun 2007–Dec 2009) |

|

| 15 | Msemo et al22 | Tanzania | Pre–Post training | 30 months (2009–2013) |

|

| 16 | Goudar et al23 | India | Pre–Post training (pretraining vs post HBB) | 12 months (Oct 2009–Sep 2010) |

|

| 17 | Vossius et al77 | Tanzania | Pre–Post training (pretraining vs post HBB) | 24 months (Feb 2010–Jan 2012) |

|

| 18 | Ashish et al*** | Nepal | Pre–Post training (pretraining vs post HBB) | 15 months (Jul 2012–Sep 2013) |

|

| 19 | Bellad et al27 | Kenya, India (Belgaum, Nagpur) | Pre–Post training (pretraining vs post HBB) | 24 months (Nov 2011–Oct 2013) |

|

| 20 | Patel et al*** | India (Nagpur) | Pre–Post training (pre-training vs post HBB) | 24 months (Nov 2011–Oct 2013) |

|

*Data for this study has been taken from Lee et al8.

**Data for very low birth weight (<1500 g).

***Unpublished data obtained via personal communication with the author

AAP, American Academy of Pediatrics; ENC, essential newborn care; HBB, helping babies breathe; NICHD, National Institute of Child and Human Development; NR, not reported; NRPG, Neonatal Resuscitation Program Guidelines; RCT, randomised control trial.

Table 2.

Characteristic of included studies (training and outcomes)

| Sr. No. | Author | Training |

No. of births

A: control/pre B: intervention/post |

Outcomes |

Criteria for delivery outcomes

A: inclusion B: exclusion |

|||||

| Duration | Training setting | Type | Trainers | Trainees | Assessment | |||||

| 1 | Bang et al20 | NR | Community (86 villages) |

A package of home-based neonatal care, health education including

|

NR |

|

NR | A: 1159 B: 1005 |

1. SB 2. NMR: day 7 3. Perinatal mortality |

A: NR B: NR |

| 2 | Ariawan et al* 8 | NR | Community | NRT including

|

NR | Midwives | NR | A: 9816 B: 16 053 |

1. SB 2. NMR: day 28 |

A: NR B: NR |

| 3 | Carlo et al17** | 3 days | Rural communities (7 sites in 6 countries for ENC; 88 for NRP) |

ENC sensitisation followed by in-depth NRT including

|

|

Community birth attendants | NR | A: 359 B: 273 |

1. SB 2. FSB 3. NMR: day 7 4. PNMR |

A: BW <1500 g B: NR |

| 4 | Carlo et al18 | 3 days | Rural communities (7 sites in six countries for ENC; 88 for NRP) |

ENC sensitisation followed by in-depth NRT including

|

|

Community birth attendants | NR | A: 35 017 B: 29 715 |

1. SB 2. FSB 3. NMR: day 1 4. NMR: day 7 5. PNMR |

A: BW >1500 g B: NR |

| 5 | Gill et al21 | 2 weeks | Community (rural district setting) |

NRT modified from AAP/AHA including

|

NR | 60 Community birth attendants/TBAs | One to one skills assessment | A: 1536 B: 1961 |

1. SB 2. NMR: day 7 3. NMR: day 28 4. PNMR |

A: NR B: NR |

| 6 | Zhu et al26 | NR | Hospital (1 hospital) |

NRPG curriculum established from AAP and AHA including

|

NR | Hospital birth attendants | NR | A: 1722 B: 4751 |

1. NMR: day 1 2. NMR: day 7 |

A: NR B: NR |

| 7 | Deorari et al24 | NR | Hospital (14 teaching hospitals) |

AAP/AHA-modified NRT with

|

2 Faculty member trainer per facility | Hospital-based birth attendants | No skills assessment | A: 7070 B: 25 713 |

1. NMR: day 28 | A: NR B: NR |

| 8 | Jeffery et al28 | 9 weeks | Hospital (3 tertiary care, 13 district hospitals) |

A package of perinatal practices with NRT | Australian-trained Macedonian teachers (doctors and nurses) | Doctors and nurses | MCQ, SAQ and OSCE (practical test) | A: 69 840 B: 45 458 |

1. SB 2. NMR: day 7 3. PNMR |

A: NR B: NR |

| 9 | Vakrilova et al30 | NR | Hospital (delivery rooms of city hospitals) |

French–Bulgarian Program on NRT | NR |

|

NR | A: 67 948 B: 67 647 |

1. NMR: day 7 | A: NR B: NR |

| 10 | O’Hare et al25 | 10 days training (5 days classroom+5 days delivery suite) |

Hospital (1 teaching hospital) |

NRT including

|

NR | 5 members of nursing staff | NR | A: 1296 B: 1046 |

1. SB | A: NR B: NR |

| 11 | Opiyo et al19 | 1 day | Hospital (1 maternity hospital) |

NRT including

|

Instructor completed Kenya Resuscitation Council Advanced Life Support Generic Instructor Course | Nurse/midwives | MCQ and formal test scenario evaluating skills | A: 4084 B: 4302 |

1. SB 2. NMR: day 28 |

A: NR B: NR |

| 12 | Boo31 | NR | Hospital | AAP-NRT tailored to local needs including

|

|

14 575

|

Written and practical test | A: 541 721 B: 465 140 |

1. SB 2. NMR: day 28 3. PNMR |

A: NR B: NR |

| 13 | Sorensen et al29 | 2 days | Hospital (1 referral hospital) |

ALSO a widespread EmONC

|

NR | High-level and mid-level staff involved in delivery | NR | A: 577 B: 565 |

1. SB | A: BW >1000 g B: Missing data |

| 14 | Hole et al32 | 1 day | Hospital (1 university hospital and 1 referral hospital) |

AAP modified NRT to include

|

Paediatrics residents from Stanford University |

|

Survey covering knowledge, skills and attitude | A: 3449 B: 3515 |

1. NMR: day 28 | A: NR B: NR |

| 15 | Msemo et al22 | 1 day | Hospital (3 referral hospitals, 4 regional hospitals and 1 district hospital) |

HBB training including

|

40 Trainers | Hospital birth attendants | Practical test | A: 8124 B: 78 500 |

1. SB 2. FSB 3. NMR: day 1 |

A: BW >750 g for live birth BW >1000 g for FSB |

| 16 | Goudar et al23 | 1 day | Hospital (primary health centres and rural and urban hospitals) |

HBB–AAP-based NRT

|

|

599 Birth attendants | Written and verbal MCQ, BMV by demonstration—OSCE | A: 4187 B: 5411 |

1. SB 2. FSB 3. NMR: day 28 |

A: GA >28 wks B: NR |

| 17 | Vossius et al77 | 1 day | Hospital (1 tertiary hospital) |

HBB–AAP-based NRT including

|

40 Master trainers | Hospital-based birth attendants | Knowledge and technical skills | A: 4876 B: 4734 |

1. FSB 2. NMR: day 7 |

A: NR B: NR |

| 18 | Ashish et al*** | 2 days | Hospital (1 tertiary hospital) |

HBB–AAP-based NRT with QIC; train the trainer model, paired teaching

|

NR |

|

NR | A: 9588 B: 15 520 |

1. SB 2. FSB 3. NMR: day 1 4. PNMR |

A: GA >22 wks B: NR |

| 19 | Bellad et al27 | 3 days | Hospital (39 primary, 21 secondary and 11 tertiary facilities) |

HBB–AAP-based NRT including

|

|

Hospital-based birth attendants

|

MCQ, OSCE for skills assessment | A: 15 232 B: 15 985 |

1. FSB 2. NMR: day 1 3. NMR: day 7 4. NMR: day 28 5. PNMR |

A: BW >1500 g B: BW unknown,<1500, >5500 and MSB |

| 20 | Patel et al*** | 3 days | Hospital (2 primary, 4 secondary HTML validation and 7 tertiary facilities) |

HBB–AAP-based NRT including

|

|

eHospital-based birth attendants

|

MCQ, OSCE for skills assessment | A: 38 078 B: 40 870 |

1. SB 2. FSB 3. NMR: day 1 4. NMR: day 7 6. PNMR |

A: GA >20 wks B: NR |

*Data for this study has been taken from Lee et al8.

**Data for very low-birth weight (<1500 g).

***Unpublished data obtained via personal communication with the author

AAP, American Academy of Pediatrics; AHA, American Heart Association; ALSO, Advanced Life Support in Obstetrics; BMV, bag and mask ventilation; BW, birth weight; CC, chest compression; EmONC, Emergency Obstetrics & Neonatal Care; ENC, essential newborn care; ET, endotracheal tube; FBOS, frequent brief onsite simulation; FSB, fresh stillbirth; GA, gestational age, HBB, helping babies breathe; MCQ, multiple choice questions; NICHD, National Institute of Child and Human Development; NMR, neonatal mortality rate; NORAD, Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation; NR, not reported; NRPG, Neonatal Resuscitation Program Guidelines; NRT, neonatal resuscitation training; OSCE, objective structured clinical evaluation; PNMR, perinatal mortality rate; PPV, positive pressure ventilation; QI, quality improvement; QIC, quality improvement cycle; RCT, randomised control trial; SAQ, short answer questions; SB, all stillbirth; TBA, traditional birth attendants; ToT, training of trainer; wks, weeks.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two authors (SB, KK) independently assessed risk of bias for each study using criteria suggested by Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care (EPOC)12 and using criteria outlined in Chapter 8 of Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.13 Disagreements were resolved by discussion with the third reviewer (MNK).

Data analysis

Measures of treatment effect

We conducted meta-analysis and reported pooled statistics as risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CIs) for dichotomous data. We followed recommendations of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Sections 9.2 and 9.4 for measuring the effects.13

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity amongst studies by inspecting forest plots for the overlap of confidence intervals, analysed statistical heterogeneity through Χ2 test (P value >0.10) and quantified through I2 statistics(Chapter 9.5 of Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews).13 We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if in the Χ2 test for heterogeneity there was either I2>50%, or P value <0.10. We interpreted I2 values between 0% and 40% as possibly unimportant, 30% and 60% as possibly significant, 50% and 90% as possibly substantial and 75% and 100% as possibly considerable.

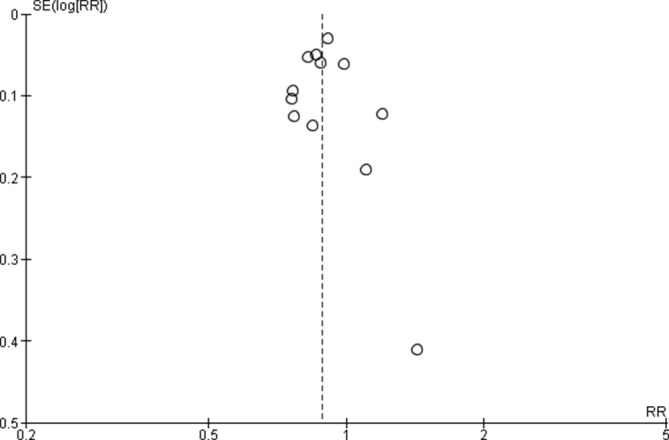

Assessment of reporting bias

We used funnel plots for assessment of publication bias if ten or more studies were included in a meta-analysis.

Data synthesis and analysis

We analysed the data using Review Manager V.5.3 software.14 We conducted meta-analyses for individual studies and reported pooled statistics as relative risk (RR) between experimental and control groups with 95% CI. We explored possible clinical and methodological reasons for heterogeneity, and in the presence of significant heterogeneity, we carried out sensitivity analysis and employed inverse-variance method with Random-effects model. We did not pool randomised and non-randomised (pre–post NRT) studies in the same meta-analysis.

Summary of findings table

We created ‘summary of findings’ (SoF) table using five GRADE considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the quality of a body of evidence. We used methods and recommendations described in Chapter 12 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions13 using GRADEpro software.15 GRADE working Group grades of evidence were used in the SoF.16

Results

Search results

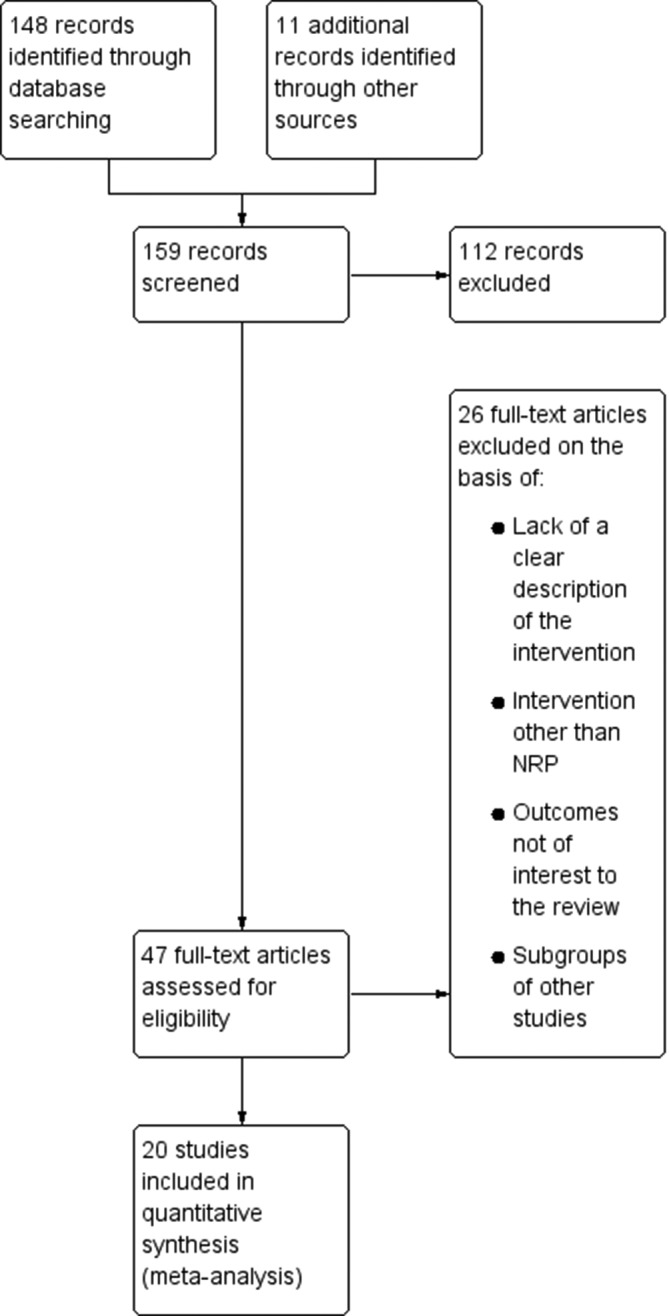

We identified 148 records through database searching and 11 records through other sources. After initial screening on the basis of title and abstract, we assessed 47 full-text articles for eligibility and finally included 20 articles in the meta-analysis. The screening details are presented in a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study selection process. NRP, Neonatal Resuscitation Program.

Included studies

Amongst included studies, two randomised trials addressed the efficacy of NRT in improving neonatal and perinatal outcomes, whereas 18 were pre–post studies. A full description of each study is included in table 1 and 2. All studies were from low-income and middle-income countries. Four studies were done in community setting, whereas 16 studies were carried in hospital setting.

Carlo et al17 18 assessed baseline perinatal outcomes, then imparted Essential Newborn Care (ENC) training to all which also included basic steps of NRT. They then randomised all clusters that had received ENC training into two groups. One group received an in-depth NRT while the other group did not (control group). For this study we evaluated the pre-ENC outcome of all clusters and compared them to outcomes of those clusters that received ENC +post ENC in-depth NRT. We therefore did not include this study in the NRT versus control analysis because the control group had also received NRT as a part of ENC training.

The study from Kenya had a complex design of randomisation of health workers to two groups—early training (phase I) or late training (phase II) and did not include a control group without training.19 Therefore, we analysed this study as before–after study where the rate of stillbirths prior to any training were compared with the rate of stillbirths after all phases of training.

Participants of the NRT programme differed across studies and included village health workers, community birth attendants,17 18 20 community birth attendants/traditional birth attendants,21 hospital-based birth attendants,19 22–26 or hospital-based birth attendants including high-level and mid-level staff/specialists.27–34

Different types of training employed by studies included AAP, HBB or NRP curricula23 24 27 31 32 34 35 AAP/American Heart Association (AHA),21 24 26 basic neonatal resuscitation and ENC,17–19 25 home-based neonatal care, basic training with mouth to mask or tube and mask resuscitation,35 Advanced Life Support in Obstetrics (ALSO),29 Bulgarian program on NRT.30 The duration of NRT also differed acrossstudies.

We also included two unpublished trials after permission from authors (tables 1 and 2).

Excluded studies

Studies that included interventions that did not qualify as NRT were excluded from the review. These included trainings in safe birthing techniques,36 Emergency Obstetric and Neonatal Care (EmONC),37 38 ENC,39–41promotion of antenatal care and maternal health education,42and newborn care intervention package.43

Other interventions that did not qualify as NRT44–50 or included interventions like neonatal intensive care unit/special neonatal care unit training51 52 were also excluded.

Studies in which desired outcomes (fetal and neonatal outcome) were not assessed,53–58 or only trainees/training outcomes were assessed,59–73 were also excluded from the analysis.

Some studies that were subgroups of larger studies like Ersdal et al.74 75 (subgroup of Msemo et al22), Matendo et al76(subgroup of Carlo et al18), Matendo et al76 and Vossius et al77 (subgroup of Msemo et al22) were also not included. However, Vossius et al77 was included in the analysis for outcomes where data from22 Msemo et al22 were not available.

Risk of bias in included studies has been depicted in table 3.

Table 3.

Risk of bias assessment across studies

| Bang et al20 |

Carlo et al17 |

Carlo et al18 |

Gill et al21 |

Zhu et al26 |

Deorari et al24 |

Jeffery et al28 |

O’Hare et al25 |

Opiyo et al19 |

Boo31 | Sorensen et al29 |

Hole et al32 |

Msemo et al22 |

Goudar et al23 |

Vossius et al77 |

Ashish et al (Unpublished data) | Bellard et al |

Patel et al (Unpublished data) | |

| Adequate sequence generation? | High risk | Low risk | ||||||||||||||||

| Allocation concealment? | High risk | Low risk | ||||||||||||||||

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Free of other bias? | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Uncleat risk | Low risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Unclear risk | High risk | Low risk | High risk | Unclear risk |

| Baseline outcomes similar? | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | unclear risk | Uncleat risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | ||

| Free of contamination? | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | ||

| Baseline characteristics similar? | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Unclear risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk |

Effects of interventions

Neonatal and perinatal outcomes were reported in majority of included studies. The overall analysis showed a trend towards reduction in neonatal deaths, early neonatal deaths, perinatal deaths and stillbirths with NRT; most of which are statistically significant.

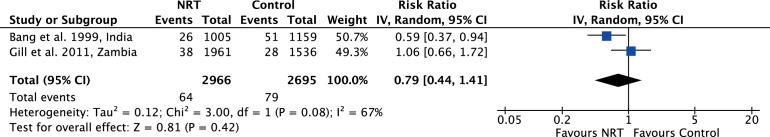

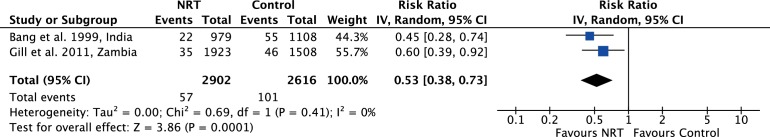

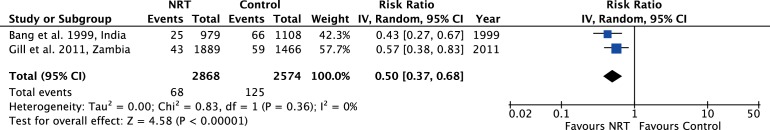

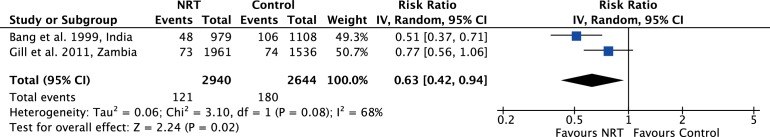

NRT verses control

The meta-analysis for NRT verses control shows that NRT decreases the risk of all stillbirths by 21% (RR 0.79, 95% CI 0.44 to 1.41; participants=5661; studies=2; I2=67%) (figure 2), 7-day neonatal deaths by 47% (RR 0.53, 95% CI 0.38 to 0.73; participants=5518; studies=2; I2=0%) (figure 3), 28-day neonatal deaths by 50% (RR 0.50, 95% CI 0.37 to 0.68; participants=5442; studies=2; I2=0%) (figure 4), and perinatal deaths by 37% (RR 0.63, 95% CI 0.42 to 0.94; participants=5584; studies=2; I2=68%)(figure 5). The effect was significant for ay 7-day neonatal mortality, 28-day neonatal mortality and perinatal mortality. Significant heterogeneity was observed in analysis of total stillbirths and perinatal mortality.

Figure 2.

Forest plot comparing all SB between the NRT and the control groups. NRT, neonatal resuscitation training; SB, stillbirths.

Figure 3.

Forest plot comparing 7-day neonatal mortality between the NRT and the control groups. NRT, neonatal resuscitation training.

Figure 4.

Forest plot comparing 28-day neonatal mortality between the NRT and the control groups. NRT, neonatal resuscitation training.

Figure 5.

Forest plot comparing perinatal mortality between the NRT and the control groups. NRT, neonatal resuscitation training.

The grade of quality of evidence for the meta-analysis of the trials was moderate to high (table 4).

Table 4.

Summary of findings for NRT versus control groups

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects (95% CI) – risk with no NRP |

Anticipated absolute effects (95% CI) – risk with NRP |

Relative effect (95% CI) |

No of participants (studies) |

Quality of the evidence (GRADE) |

| All stillbirth | 29 per 1000 | 23 per 1000 (13 to 41) |

RR 0.79 (0.44 to 1.41) |

5661 (2 RCTs) |

⨁◯◯◯ Very low*† |

| Fresh stillbirth | Outcome not reported | Outcome not reported | Outcome not reported | Outcome not reported | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low‡ |

| 1-day neonatal mortality | Outcome not reported | Outcome not reported | Outcome not reported | Outcome not reported | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low‡ |

| 7-day neonatal mortality | 39 per 1000 | 20 per 1000 (15 to 28) |

RR 0.53 (0.38 to 0.73) |

5518 (2 RCTs) |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ High |

| 28-day neonatal mortality | 49 per 1000 | 24 per 1000 (18 to 33) |

RR 0.50 (0.37 to 0.68) |

5442 (2 RCTs) |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ High |

| Perinatal mortality | 68 per 1000 | 43 per 1000 (29 to 64) |

RR 0.63 (0.42 to 0.94) |

5584 (2 RCTs) |

⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate§ |

*I2 is 67% and the two trials were inconsistent in the direction of effect. Quality of evidence downgraded by two for inconsistency and imprecision (figure 2).

†The 95% CI of the pooled estimate includes null effect. Quality of evidence downgraded by one for imprecision (figure 2).

‡No evidence to support or refute.

§Though I2 is 68%, the 95% CI of the pooled estimate does not include the null effect. Quality of evidence downgraded by one for inconsistency (figure 5).

NRT, neonatal resuscitation training; RCTs, randomised controlled trial; RR, risk ratio.

Post-NRT verses pre-NRT

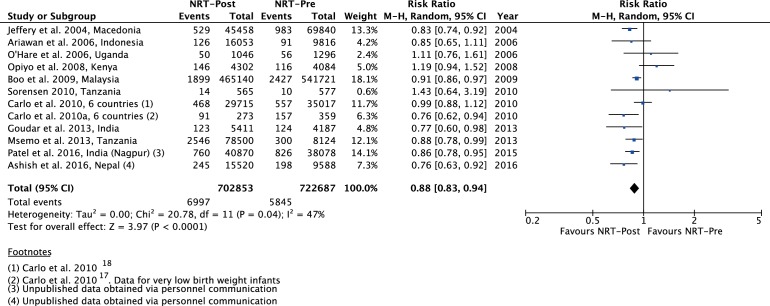

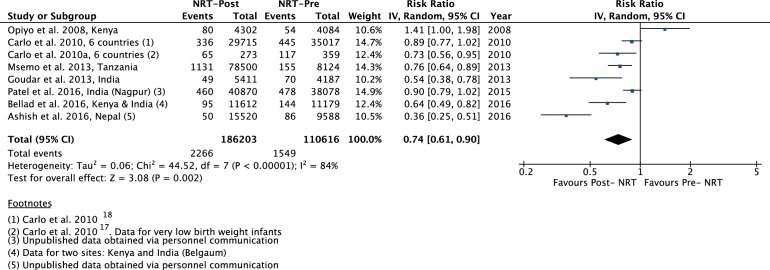

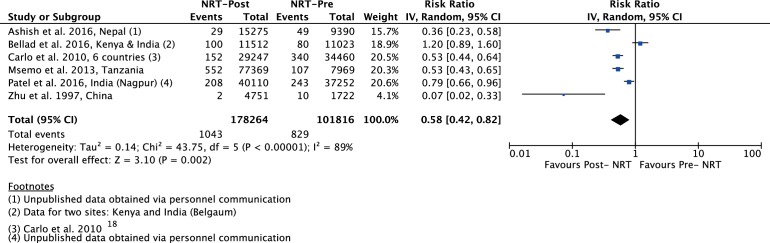

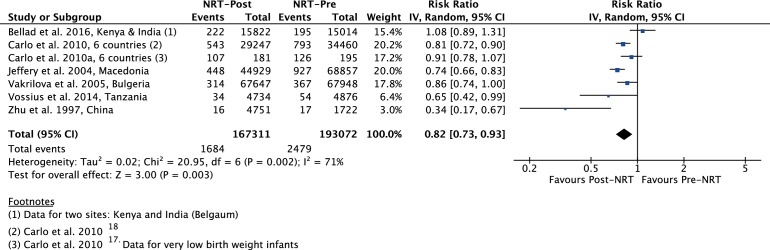

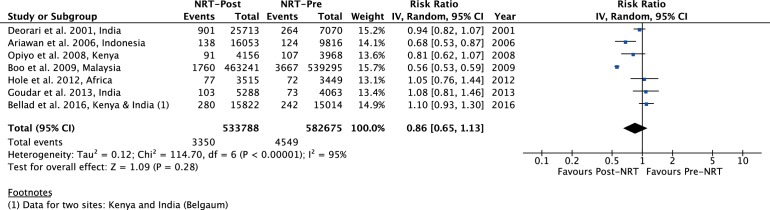

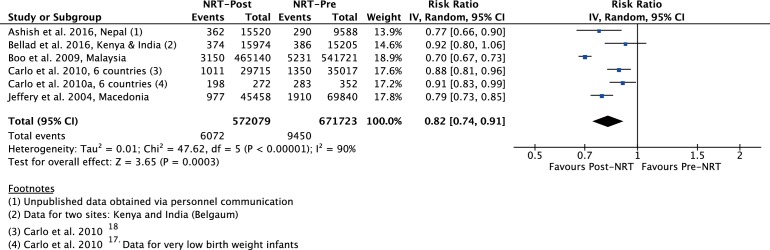

The meta-analysis of post-NRT verses pre-NRT shows that post-NRT decreases the risk of all stillbirths by 12% (RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.83 to 0.94; participants=1 425 540; studies=12; I2=47%, figure 6), fresh stillbirths by 26% (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.61 to 0.90; participants=296 819; studies=8; I2=84%, figure 7), 1-day neonatal mortality by 42% (RR 0.58, 95% CI 0.42 to 0.82; participants=280 080; studies=6; I2=89%, figure 8), 7-day neonatal mortality by 18% (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.73 to 0.93; participants=360 383; studies=7; I2=71%, figure 9), 28-day neonatal mortality by 14% (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.13; participants=1 116 463; studies=7; I2=95%, figure 10) and perinatal mortality by 18% (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.74 to 0.91; participants=1 243 802; studies=6; I2=90%, figure 11). The changes were significant in all the outcomes; except 28-day neonatal mortality. Heterogeneity was significant in all outcomes except all stillbirths. We created a funnel plot for all stillbirths, which showed asymmetry, thereby indicating a publication bias (figure 12).

Figure 6.

Forest plot comparing all SB between the post-NRT and the pre-NRT groups. NRT, neonatal resuscitation training; SB, stillbirths.

Figure 7.

Forest plot comparing fresh SB between the post-NRT and the pre-NRT groups. NRT, neonatal resuscitation training; SB, stillbirths.

Figure 8.

Forest plot comparing 1-day neonatal mortality between the post-NRT and the pre-NRT groups. NRT, neonatal resuscitation training.

Figure 9.

Forest plot comparing 7-day neonatal mortality between the post-NRT and the pre-NRT groups. NRT, neonatal resuscitation training.

Figure 10.

Forest plot comparing 28-day neonatal mortality between the post-NRT and the pre-NRT groups. NRT, neonatal resuscitation training.

Figure 11.

Forest plot comparing perinatal m between the post-NRT and the pre-NRT groups. NRT, neonatal resuscitation training.

Figure 12.

Funnel plot of comparison: Post-NRT verses pPre-NRT for all SB. NRT, neonatal resuscitation training; RR, risk ratio; SB, stillbirths.

The quality of evidence for NRT verses control was very low for SB and 1-day neonatal mortality, high for 7-day and 28-day neonatal mortality and moderate for perinatal mortality (table 4). The quality of evidence for post-NRT verses pre-NRT was very low for all our outcomes (table 5).

Table 5.

Summary of findings for Post-NRT versus Pre-NRT groups

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects (95% CI) Risk with pre-NRP |

Anticipated absolute effects (95% CI) Risk with post-NRP |

Relative effect (95% CI) |

No of participants (studies) |

Quality of the evidence (GRADE) |

| All stillbirths | 8 per 1000 | 7 per 1000 (7 to 8) | RR 0.88 (0.83 to 0.94) | 1 425 540 (12 observational studies) | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low*†‡ |

| Fresh stillbirths | 15 per 1000 | 11 per 1000 (9 to 13) | RR 0.74 (0.61 to 0.90) | 296 819 (8 observational studies) | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low*†§ |

| 1-day neonatal mortality | 8 per 1000 | 5 per 1000 (4 to 7) | RR 0.58 (0.42 to 0.82) | 280 080 (6 observational studies) | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low *¶ |

| 7-day neonatal mortality | 13 per 1000 | 11 per 1000 (9 to 12) | RR 0.82 (0.73 to 0.93) | 360 383 (7 observational studies) | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low *† ** |

| 28-day neonatal mortality | 8 per 1000 | 7 per 1000 (5 to 9) | RR 0.86 (0.65 to 1.13) | 1 116 463 (7 observational studies) | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low * †† |

| Perinatal mortality | 14 per 1000 | 12 per 1000 (10 to 13) | RR 0.82 (0.74 to 0.91) | 1 243 802 (6 observational studies) | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low * §§ ¶¶ |

*Pre–post studies. Quality of evidence downgraded by one for risk of bias (table 1 and 2).

Studies differ in the settings, type of NRP, duration and type trainees. Quality of evidence downgraded by one for indirectness (table 1 and 2).

Publication bias detected in the funnel plot. Quality of evidence downgraded by one for publication bias (figure 12).

Although I2 is 84%, the effect estimates of all included studies do not differ in the direction of effect. Quality of effect downgraded by one for inconsistency (figure 7).

Although I2 is 89%, the effect estimates of all the included studies (except Bellard et al.) do not differ in the direction of effect. Quality of effect downgraded by one for inconsistency (figure 8).

Although I2 is 71%, the effect estimates of all the included studies (except Bellard et al.) do not differ in the direction of effect. Quality of effect downgraded by one for inconsistency (figure 9).

I2 is 95% and the effect estimates cross the life of no effect. Quality of evidence downgraded by two for inconsistency and imprecision (figure 10).

‡‡The effect estimate crosses the line of no effect. Quality of evidence downgraded by one for imprecision (figure 10).

Although I2 is 90%, the effect estimates of all the included studies do not differ in the direction of effect. Quality of effect downgraded by one for inconsistency (figure 11).

Studies differ in setting, type of NRP and trainees. Quality of evidence downgraded by one for indirectness (table 1 and 2).

NRP, Neonatal Resuscitation Program; NRT, neonatal resuscitation trainings; RR, risk ratio; SB, stillbirths.

Discussion

This meta-analysis assessed the impact of any NRT programme either by itself or as a part of newborn care package on rates of stillbirths, perinatal mortality, all-cause neonatal mortality on day-1, up till day-7 and till 28th day after birth. We did not evaluate intrapartum-related neonatal deaths or asphyxia/cause-specific neonatal mortality. Mortality in neonates <7 days of life is a proxy measure for intrapartum-related deaths.43 78 Meta-analysis of before–after studies showed a significant reduction in all stillbirths by 12% (12 studies) and of FSB by 26% (8 studies). The reduction in fresh stillbirths can be attributed to NRT that helps in resuscitating neonates that appear lifeless at birth.17 18 Of 12 studies, seven studies reported a significant and one study reported a non-significant reduction in fresh stillbirths. However, a non-significant increase in risk of stillbirths was reported in three African studies which blunted the impact of NRT on reduction of stillbirths.

There was reduction in 1-day mortality of 42% (6 studies) and that of 7-day mortality was 18%. All studies included in the analysis (figures 8 and 9) showed a reduction with an exception of one study.27 Failure to observe reduction in mortality in Bellad et al could be due to two reasons. First, NRT was provided in diverse health systems within a short period of time. Second, mortality was not assessed in facilities where training was imparted but was measured in the population.

The meta-analysis showed a non-significant reduction of 14% in 28-day mortality. Of the seven included studies only two studies reported a significant reduction in mortality. Resuscitation at delivery helps to reduce neonatal mortality in the first hour of birth when the neonate is at the highest risk of intrapartum-related deaths3 and the impact diminishes subsequently. For reduction of 28-day neonatal mortality, post-resuscitation specialised care for survivors is required and only NRT is unlikely to have the desired impact on 28-day neonatal mortality.79 80

Trials that randomise facilities to NRT versus controls (where NRT is not a standard practice) would be ideal to assess the reduction in neonatal mortality. Trials are also likely to result in higher impact as compared with before–after studies as other changes at health facilities or in communities during the time period of before–after studies can confound the results. Because NRT is a standard practice and randomising individuals or clusters to no resuscitation training is unethical, there were only two trials available for the meta-analysis.20 21 They showed a reduction of 7-day neonatal mortality and 28-day mortality by 47% (figure 3) and 50% (figure 4), respectively. The perinatal mortality reduced by 37% (figure 5) with no significant reduction in SB rates.

Previously, an expert panel published a systematic review for community-based studies and conducted a meta-analysis that evaluated whether NRT reduced all-cause neonatal mortality in th first 7 days of life. They reported a 38% reduction in mortality which is larger than the 18% (7 studies) reduction observed in the current meta-analysis. Our meta-analysis included community-based studies that resulted in a smaller effect size. Community-based studies (trials or before–after) report a smaller reduction effect on any day neonatal mortality.8 17 18 47 The reduction in effect size of neonatal mortality in these studies can arise due to several reasons. All births in the intervention community may not be attended by birth attendants trained in neonatal resuscitation, especially if it is a home delivery.81 82 Second, women may decide to deliver at facilities or homes outside communities where NRT has been imparted. Finally, assessing mortality outcomes in the community can be challenging. Another meta-analysis11 was published in Cochrane which evaluated outcomes such as knowledge, skills, neonatal morbidity, neonatal mortality in first 7 days after birth and from day 8 to 28. This analysis did not include stillbirths, 1-day neonatal mortality or perinatal mortality that was included in the current meta-analysis.

The current meta-analysis consists largely of before–after studies with lack of concurrent control group that limits isolation of effect of resuscitation training alone from other changes at health facilities or in communities during the time period. Other limitation is lack of consistency of settings, duration of training, varying study designs and lack of consistent outcomes which contributed to substantial heterogeneity. Lack of subgroup analysis of type of health facilities may be perceived as a limitation. An improvement in mortality would be maximised in low-resource settings with poor quality of care. However, it is presumed that there is regular training of health workers in basic resuscitation skills in higher levels of care that would translate to higher quality of care. Our recent study83 84 that evaluated the knowledge and skills of trainees trained in HBB included 384 tertiary-level facilities in India. Only 3% of physicians and 5% of nurses were able to pass the pre-training bag and mask resuscitation skill assessment.84 Therefore, in the absence of reporting of pre-training skills of health workers in low-resource or high-resource settings or any indicator of quality of care, it would be erroneous to conduct a subgroup analysis based merely on resource settings and mostly will not change the results or the main message of this meta-analysis. We emphasise that despite the heterogeneity in settings, type of training, type of trainees, type of trainers and the duration of training, this study showed an improvement in mortality at and soon after birth.

To conclude, NRT resulted in reduction in stillbirths and improved survival of newborns. The impact on survival of newborns can be further improved by providing a continuum of care beyond 7 days which is not addressed by NRT alone.

The meta-analysis performed showed beneficial effect of NRT in improving neonatal and perinatal outcomes. The models of training were not consistent across studies, with variations in training, trainee and setting. Generalisation of results of the pooled analysis to many currently available programme may not be appropriate. There was evidence of heterogeneity across studies in our meta-analyses; however, overall there is consistency in the direction of effect.

This review identified several important limitations of the current evidence from included studies. Due to inadequate information about the methodology followed and variety of resuscitation programmes in included studies, the quality of the evidence was downgraded for risk of bias and indirectness resulting in inability to adequately assess the effects of this intervention.

Conclusions

Implications for practice

This review shows that the implementation of NRT improves neonatal and perinatal outcomes.

Implications for research

Further good quality, multicentric randomised controlled trials addressing the role of NRT for improving neonatal and perinatal outcomes may be warranted. Impact of NRT on improving neonatal and perinatal outcomes as well as the best combination of settings and type of trainee should be established in future trials. More studies need to be done to assess the frequency with which NRT needs to be conducted to sustain the existing effect on perinatal mortality reduction.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Richard Kirubhakaran (Research Scientist, Cochrane South Asia, Prof B V Moses Centre for Evidence-Informed Healthcare & Health Policy, Christian Medical College, Vellore) for his inputs on meta-analysis and Lauren Arlington, Partner Healthcare, for her help in getting the full text of the articles required for this review.

Footnotes

Contributors: AP: conception of the work, design of the work, manuscript drafting with final approval of the version to be published. MNK: developed and run the search strategy, screened and selected studies, and did meta-analysis, GRADE assessment and manuscript drafting. KK and SB: involved in preparation of characteristic of studies table, data acquisition and manuscript drafting. AB: screening and selection of studies, data acquisition and manuscript drafting.

Funding: This work was supported by Lata Medical Research Foundation, Nagpur, India (Grant no: LMRF/GRP02/072016).

Competing interests: The authors AP and AB were investigators in two of the studies (Bellad et al and Patel et al) included in the meta-analysis. There were no other competing interest.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.David M, Mark D. Obstetrics & Gynaecology: an evidence-based text for MRCOG. 3rd edition London, United Kingdom: Taylor Francis Ltd, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Australian resuscitation council, New Zealand resuscitation council. The resuscitation of the newborn infant in special circumstances. ARC and NZRC guideline 2010. Emerg Med Australas 2011;23:445–7. doi:10.1111/j.1742-6723.2011.01442_15.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wall SN, Lee AC, Niermeyer S, et al. Neonatal resuscitation in low-resource settings: what, who, and how to overcome challenges to scale up? Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2009;107(Suppl 1):S47–S64. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.07.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palme-Kilander C. Methods of resuscitation in low-apgar-score newborn infants-a national survey. Acta Paediatr 1992;81:739–44. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.1992.tb12094.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kattwinkel J, Niermeyer S, Nadkarni V, et al. Resuscitation of the newly born infant: an advisory statement from the pediatric working group of the international liaison committee on resuscitation. Resuscitation 1999;40:71–88. doi:10.1016/S0300-9572(99)00012-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation. The international liaison committee on resuscitation (ILCOR) consensus on science with treatment recommendations for pediatric and neonatal patients: neonatal resuscitation. Pediatrics 2006;117:e978–88. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-0350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sousa S, Mielke JG. Does resuscitation training reduce neonatal deaths in low-resource communities? A systematic review of the literature. Asia Pac J Public Health 2015;27:690–704. doi:10.1177/1010539515603447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee AC, Cousens S, Wall SN, et al. Neonatal resuscitation and immediate newborn assessment and stimulation for the prevention of neonatal deaths: a systematic review, meta-analysis and Delphi estimation of mortality effect. BMC Public Health 2011;11:S12 doi:10.1186/1471-2458-11-S3-S12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reisman J, Arlington L, Jensen L, et al. Newborn resuscitation training in resource-limited settings: a systematic literature review. Pediatrics 2016;138:e20154490 doi:10.1542/peds.2015-4490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American heart association, american academy of pediatrics. 2005 American heart association (AHA) guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and emergency cardiovascular care (ECC) of pediatric and neonatal patients: neonatal resuscitation guidelines. Pediatrics 2006;117:e1029–38. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-0349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dempsey E, Pammi M, Ryan AC, et al. Standardised formal resuscitation training programmes for reducing mortality and morbidity in newborn infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015:CD009106 (accessed 9 Oct 2016). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009106.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care. Suggested risk of bias criteria for EPOC reviews. http://epoc.cochrane.org/sites/epoc.cochrane.org/files/public/uploads/Resources-for-authors2017/suggested_risk_of_bias_criteria_for_epoc_reviews.pdf (accessed 27 Sep 2017).

- 13.Cochrane Training. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. http://training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed 8 Oct 2016).

- 14.The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 5.3. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15.GRADEpro | GDT. GRADE’s software for summary of findingstables, health technology assessmentand guidelines. https://gradepro.org/ (accessed 27 Sep 2017).

- 16.GRADE. GRADE handbook (SA version). http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/app/handbook/handbook.html (accessed 8 Oct 2016).

- 17.Carlo WA, Goudar SS, Jehan I, et al. High mortality rates for very low birth weight infants in developing countries despite training. Pediatrics 2010;126:e1072–e1080. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-1183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carlo WA, Goudar SS, Jehan I, et al. Newborn-care training and perinatal mortality in developing countries. N Engl J Med 2010;362:614–23. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa0806033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Opiyo N, Were F, Govedi F, et al. Effect of newborn resuscitation training on health worker practices in Pumwani Hospital, Kenya. PLoS One 2008;3:e1599 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bang AT, Bang RA, Baitule SB, et al. Effect of home-based neonatal care and management of sepsis on neonatal mortality: field trial in rural India. Lancet 1999;354:1955–61. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(99)03046-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gill CJ, Phiri-Mazala G, Guerina NG, et al. Effect of training traditional birth attendants on neonatal mortality (lufwanyama neonatal survival project): randomised controlled study. BMJ 2011;342:d346 doi:10.1136/bmj.d346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Msemo G, Massawe A, Mmbando D, et al. Newborn mortality and fresh stillbirth rates in tanzania after helping babies breathe training. Pediatrics 2013;131:e353–e360. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-1795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goudar SS, Somannavar MS, Clark R, et al. Stillbirth and newborn mortality in India after helping babies breathe training. Pediatrics 2013;131:e344–e352. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-2112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deorari AK, Paul VK, Singh M, et al. Impact of education and training on neonatal resuscitation practices in 14 teaching hospitals in India. Ann Trop Paediatr 2001;21:29–33. doi:10.1080/02724930123814 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Hare BA, Nakakeeto M, Southall DP. A pilot study to determine if nurses trained in basic neonatal resuscitation would impact the outcome of neonates delivered in Kampala, Uganda. J Trop Pediatr 2006;52:376–9. doi:10.1093/tropej/fml027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu XY, Fang HQ, Zeng SP, et al. The impact of the neonatal resuscitation program guidelines (NRPG) on the neonatal mortality in a hospital in Zhuhai, China. Singapore Med J 1997;38:485–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bellad RM, Bang A, Carlo WA, et al. A pre-post study of a multi-country scale up of resuscitation training of facility birth attendants: does Helping Babies Breathe training save lives? BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016;16:222 doi:10.1186/s12884-016-0997-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jeffery HE, Kocova M, Tozija F, et al. The impact of evidence-based education on a perinatal capacity-building initiative in macedonia. Med Educ 2004;38:435–47. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2923.2004.01785.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sorensen BL, Rasch V, Massawe S, et al. Impact of ALSO training on the management of prolonged labor and neonatal care at kagera regional hospital, tanzania. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2010;111:8–12. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.04.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vakrilova L, Elleau C, Slŭncheva B. [French-Bulgarian program "Resuscitation of the newborn in a delivery room"--results and perspectives]. Akush Ginekol 2005;44:35–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boo NY. Neonatal resuscitation programme in Malaysia: an eight-year experience. Singapore Med J 2009;50:152–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hole MK, Olmsted K, Kiromera A, et al. A neonatal resuscitation curriculum in Malawi, Africa: did it change in-hospital mortality? Int J Pediatr 2012;2012:1–8. doi:10.1155/2012/408689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kc A, Wrammert J, Clark RB, et al. Reducing perinatal mortality in nepal using helping babies breathe. Pediatrics 2016;137:e20150117 doi:10.1542/peds.2015-0117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patel A, Bang A, Kurhe K, et al. Impact of implementation of ‘helping babies breathe (HBB)’ training program on all cause and asphyxia specific mortality in selected health facilities. Unpubl Data 2013;16:364. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bang AT, Bang RA, Tale O, et al. Reduction in pneumonia mortality and total childhood mortality by means of community-based intervention trial in Gadchiroli, India. Lancet 1990;336:201–6. doi:10.1016/0140-6736(90)91733-Q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O’Rourke K, Howard-Grabman L, Seoane G. Impact of community organization of women on perinatal outcomes in rural Bolivia. Rev Panam Salud Publica 1998;3:9–14. doi:10.1590/S1020-49891998000100002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pasha O, Goldenberg RL, McClure EM, et al. Communities, birth attendants and health facilities: a continuum of emergency maternal and newborn care (the Global Network’s EmONC trial). BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2010;10:82 doi:10.1186/1471-2393-10-82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pasha O, McClure EM, Wright LL, et al. A combined community- and facility-based approach to improve pregnancy outcomes in low-resource settings: a global network cluster randomized trial. BMC Med 2013;11:215 doi:10.1186/1741-7015-11-215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kirkwood BR, Manu A, ten Asbroek AH, et al. Effect of the newhints home-visits intervention on neonatal mortality rate and care practices in ghana: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2013;381:2184–92. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60095-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kumar V, Kumar A, Das V, et al. Community-driven impact of a newborn-focused behavioral intervention on maternal health in Shivgarh, India. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2012;117:48–55. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2011.10.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kumar V, Mohanty S, Kumar A, et al. Effect of community-based behaviour change management on neonatal mortality in Shivgarh, Uttar Pradesh, India: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2008;372:1151–62. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61483-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bhutta ZA, Soofi S, Cousens S, et al. Improvement of perinatal and newborn care in rural Pakistan through community-based strategies: a cluster-randomised effectiveness trial. Lancet 2011;377:403–12. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62274-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baqui AH, El-Arifeen S, Darmstadt GL, et al. Effect of community-based newborn-care intervention package implemented through two service-delivery strategies in Sylhet district, Bangladesh: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2008;371:1936–44. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60835-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tripathy P, Nair N, Barnett S, et al. Effect of a participatory intervention with women’s groups on birth outcomes and maternal depression in jharkhand and orissa, india: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2010;375:1182–92. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62042-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Manandhar DS, Osrin D, Shrestha BP, et al. Effect of a participatory intervention with women’s groups on birth outcomes in Nepal: cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2004;364:970–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17021-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Azad K, Barnett S, Banerjee B, et al. Effect of scaling up women’s groups on birth outcomes in three rural districts in bangladesh: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2010;375:1193–202. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60142-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pratinidhi A, Shah U, Shrotri A, et al. Risk-approach strategy in neonatal care. Bull World Health Organ 1986;64:291–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Daga SR, Fernandes CJ, Soares M, et al. Clinical profile of severe birth asphyxia. Indian Pediatr 1991;28:485–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chomba E, McClure EM, Wright LL, et al. Effect of WHO newborn care training on neonatal mortality by education. Ambul Pediatr 2008;8:300–4. doi:10.1016/j.ambp.2008.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Berglund A, Lefevre-Cholay H, Bacci A, et al. Successful implementation of evidence-based routines in Ukrainian maternities. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2010;89:230–7. doi:10.3109/00016340903479894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mufti P, Setna F, Nazir K. Early neonatal mortality: effects of interventions on survival of low birth babies weighing 1000-2000g. J Pak Med Assoc 2006;56:174–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sen A, Mahalanabis D, Singh AK, et al. Impact of a district level sick newborn care unit on neonatal mortality rate: 2-year follow-up. J Perinatol 2009;29:150–5. doi:10.1038/jp.2008.177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Patel D, Piotrowski ZH, Nelson MR, et al. Effect of a statewide neonatal resuscitation training program on Apgar scores among high-risk neonates in Illinois. Pediatrics 2001;107:648–55. doi:10.1542/peds.107.4.648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Patel D, Piotrowski ZH. Positive changes among very low birth weight infant apgar scores that are associated with the neonatal resuscitation program in Illinois. J Perinatol 2002;22:386–90. doi:10.1038/sj.jp.7210751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Draycott T, Sibanda T, Owen L, et al. Does training in obstetric emergencies improve neonatal outcome? BJOG 2006;113:177–82. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.00800.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Duran R, Görker I, Küçükuğurluoğlu Y, et al. Effect of neonatal resuscitation courses on long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes of newborn infants with perinatal asphyxia. Pediatr Int 2012;54:56–9. doi:10.1111/j.1442-200X.2011.03463.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Duran R, Aladağ N, Vatansever U, et al. Proficiency and knowledge gained and retained by pediatric residents after neonatal resuscitation course. Pediatr Int 2008;50:644–7. doi:10.1111/j.1442-200X.2008.02637.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xu T, Wang H, Gong L, et al. The impact of an intervention package promoting effective neonatal resuscitation training in rural China. Resuscitation 2014;85:253–9. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.10.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bookman L, Engmann C, Srofenyoh E, et al. Educational impact of a hospital-based neonatal resuscitation program in Ghana. Resuscitation 2010;81:1180–2. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.04.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hoban R, Bucher S, Neuman I, et al. ’Helping babies breathe' training in sub-saharan africa: educational impact and learner impressions. J Trop Pediatr 2013;59:180–6. doi:10.1093/tropej/fms077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Singhal N, Lockyer J, Fidler H, et al. Helping babies breathe: global neonatal resuscitation program development and formative educational evaluation. Resuscitation 2012;83:90–6. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2011.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Enweronu-Laryea C, Engmann C, Osafo A, et al. Evaluating the effectiveness of a strategy for teaching neonatal resuscitation in west africa. Resuscitation 2009;80:1308–11. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ryan CA, Ahmed S, Abdullah H, et al. Dissemination and evaluation of AAP/AHA neonatal resuscitation programme in ireland. Ir Med J 1998;91:51–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Halamek LP, Kaegi DM, Gaba DM, et al. Time for a new paradigm in pediatric medical education: teaching neonatal resuscitation in a simulated delivery room environment. Pediatrics 2000;106:e45 doi:10.1542/peds.106.4.e45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thomas EJ, Williams AL, Reichman EF, et al. Team training in the neonatal resuscitation program for interns: teamwork and quality of resuscitations. Pediatrics 2010;125:539–46. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-1635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Thomas EJ, Taggart B, Crandell S, et al. Teaching teamwork during the neonatal resuscitation program: a randomized trial. J Perinatol 2007;27:409–14. doi:10.1038/sj.jp.7211771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Couper ID, Thurley JD, Hugo JF. The neonatal resuscitation training project in rural south africa. Rural Remote Health 2005;5:459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nadel FM, Lavelle JM, Fein JA, et al. Assessing pediatric senior residents' training in resuscitation: fund of knowledge, technical skills, and perception of confidence. Pediatr Emerg Care 2000;16:73–6. doi:10.1097/00006565-200004000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nadel FM, Lavelle JM, Fein JA, et al. Teaching resuscitation to pediatric residents: the effects of an intervention. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2000;154:1049–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kurosawa H, Ikeyama T, Achuff P, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of in situ pediatric advanced life support recertification ("pediatric advanced life support reconstructed") compared with standard pediatric advanced life support recertification for ICU frontline providers*. Crit Care Med 2014;42:610–8. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000000024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ergenekon E, Koç E, Atalay Y, et al. Neonatal resuscitation course experience in turkey. Resuscitation 2000;45:225–7. doi:10.1016/S0300-9572(00)00179-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Quan L, Shugerman RP, Kunkel NC, et al. Evaluation of resuscitation skills in new residents before and after pediatric advanced life support course. Pediatrics 2001;108:e110 doi:10.1542/peds.108.6.e110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Curran V, Fleet L, White S, et al. A randomized controlled study of manikin simulator fidelity on neonatal resuscitation program learning outcomes. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2015;20:205–18. doi:10.1007/s10459-014-9522-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ersdal HL, Vossius C, Bayo E, et al. A one-day "helping babies breathe" course improves simulated performance but not clinical management of neonates. Resuscitation 2013;84:1422–7. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ersdal HL, Singhal N. Resuscitation in resource-limited settings. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 2013;18:373–8. doi:10.1016/j.siny.2013.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Matendo R, Engmann C, Ditekemena J, et al. Reduced perinatal mortality following enhanced training of birth attendants in the democratic republic of congo: a time-dependent effect. BMC Med 2011;9:93 doi:10.1186/1741-7015-9-93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vossius C, Lotto E, Lyanga S, et al. Cost-effectiveness of the "helping babies breathe" program in a missionary hospital in rural Tanzania. PLoS One 2014;9:e102080 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0102080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Edmond KM, Quigley MA, Zandoh C, et al. Aetiology of stillbirths and neonatal deaths in rural Ghana: implications for health programming in developing countries. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2008;22:430–7. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3016.2008.00961.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Darmstadt GL, Bhutta ZA, Cousens S, et al. Evidence-based, cost-effective interventions: how many newborn babies can we save? Lancet 2005;365:977–88. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71088-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bhutta ZA, Darmstadt GL, Hasan BS, et al. Community-based interventions for improving perinatal and neonatal health outcomes in developing countries: a review of the evidence. Pediatrics 2005;115:519–617. doi:10.1542/peds.2004-1441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kumbani L, Bjune G, Chirwa E, et al. Why some women fail to give birth at health facilities: a qualitative study of women’s perceptions of perinatal care from rural southern malawi. Reprod Health 2013;10:9 doi:10.1186/1742-4755-10-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yakoob MY, Menezes EV, Soomro T, et al. Reducing stillbirths: behavioural and nutritional interventions before and during pregnancy. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2009;9:S3 doi:10.1186/1471-2393-9-S1-S3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bang A, Bellad R, Gisore P, et al. Implementation and evaluation of the helping babies breathe curriculum in three resource limited settings: does helping babies breathe save lives? a study protocol. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014;14:116 doi:10.1186/1471-2393-14-116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bang A, Patel A, Bellad R, et al. Helping Babies Breathe (HBB) training: What happens to knowledge and skills over time? BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016;16:364 doi:10.1186/s12884-016-1141-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]