SUMMARY

As gene expression measurement technology is shifting from microarrays to sequencing, the statistical tools available for their analysis must be adapted since RNA-seq data are measured as counts. It has been proposed to model RNA-seq counts as continuous variables using nonparametric regression to account for their inherent heteroscedasticity. In this vein, we propose tcgsaseq, a principled, model-free, and efficient method for detecting longitudinal changes in RNA-seq gene sets defined a priori. The method identifies those gene sets whose expression varies over time, based on an original variance component score test accounting for both covariates and heteroscedasticity without assuming any specific parametric distribution for the (transformed) counts. We demonstrate that despite the presence of a nonparametric component, our test statistic has a simple form and limiting distribution, and both may be computed quickly. A permutation version of the test is additionally proposed for very small sample sizes. Applied to both simulated data and two real datasets, tcgsaseq is shown to exhibit very good statistical properties, with an increase in stability and power when compared to state-of-the-art methods ROAST (rotation gene set testing), edgeR, and DESeq2, which can fail to control the type I error under certain realistic settings. We have made the method available for the community in the R package tcgsaseq.

Keywords: Gene Set Analysis, Longitudinal data, RNA-seq data, Variance component testing, Heteroscedasticity

1. Introduction

Gene expression is a dynamic biological process of living organisms, whose dysfunction and variation can be related to numerous diseases. During the past two decades, gene expression measurements have developed rapidly, thanks to wide dissemination of microarray technology. In recent years, gene expression measurement technology has been shifting from microarrays to sequencing (RNA-seq) technology. The higher resolution of RNA-seq technology provides a number of advantages over microarrays, among which are the ability to make de novo discoveries and an increased sensitivity to low-abundance variants (Marioni and others, 2008). Indeed, RNA-seq is not restricted to a predefined set of probes like microarrays but can instead measure the genome in its entirety.

A large body of statistical methods have been developed to analyze microarray data. But as technology for measuring gene expression is transitioning to RNA-seq, new methodological challenges arise. RNA-seq produces count data, while microarray analysis techniques generally assume continuity. Due to their underlying count nature, RNA-seq data are intrinsically heteroscedastic. Various approaches have been proposed to deal with these issues, mostly relying on modeling the underlying count nature of the data through the use of Poisson or negative binomial distributions (Marioni and others, 2008; Anders and Huber, 2010; Robinson and others, 2010). Recently, Law and others (2014). have instead proposed to use normal-based methods to analyze RNA-seq data by explicitly modeling the heteroscedasticity and accounting for it by weighting. All of these methods currently make potentially restrictive assumptions about the distribution of the data.

While most methods for gene expression data focus on univariate differential gene expression analysis, it has been shown that gene set analysis (GSA) can be a more powerful and interpretable alternative (Subramanian and others, 2005; Hejblum and others, 2015). GSA uses a priori defined gene sets annotated with biological functions and investigates their potential association with biological conditions of interest. There are many different approaches to GSA, and a GSA method is typically defined by the type of hypothesis tested as well as how information across genes is aggregated. Rahmatallah and others (2016) recently showed that self-contained GSA tests tend to be more powerful and more robust than competitive ones (Goeman and Bühlmann, 2007). Furthermore, some GSA tests rely on univariate gene-level statistics as a first step, aggregating them afterwards in a bottom-up enrichment approach. But when signal strength is weak, single-step, top-down GSA methods relying on direct multivariate modeling are better than those enrichment based ones at leveraging the additional power of GSA (Hejblum and others, 2015).

As costs keep decreasing for RNA-seq experiments, more complex study designs, such as time-course experiments, have become more common (Dorr and others, 2015; Baduel and others, 2016). However, very few GSA approaches can properly accommodate and test hypotheses more complex than simple differential expression, such as change over time. The ROAST method (Wu and others, 2010) is a linear-model-based gene set testing procedure. Law and others (2014) have proposed to use it in conjunction with their heteroscedasticity weighting method voom on RNA-seq data, and this combination of voom and ROAST has been identified in the recent review by Rahmatallah and others (2016) as one of the top-performing GSA methods for RNA-seq data. Additionally, DESeq2 (Love and others, 2014) and edgeR (Robinson and others, 2010; McCarthy and others, 2012), are currently the most prominent approaches used for gene-level differential analysis of RNA-seq data. They both rely on the assumption that gene counts from RNA-seq measurements follow a negative binomial distribution. edgeR can use the ROAST method to propose a built-in framework for self-contained gene set testing, while DESeq2 can only perform gene-wise tests. Nueda and others (2014) have also developed a gene-wise method for dealing with time-course course RNA-seq data, considering Poisson and negative binomial distributions through generalized linear models.

Another concern, particularly in the longitudinal setting, is adequately accounting for heterogeneity of effects (Cui and others, 2016). GSA approaches often overlook the potential longitudinal heterogeneity within a gene set while such heterogeneity is not infrequent (Ackermann and Strimmer, 2009) and can be of biological interest (Hu and others, 2013), especially if considered gene sets correspond to biological pathways or networks. Hejblum and others (2015) showed the potential statistical power gain when accounting for this heterogeneity in longitudinal microarray studies.

In this article, we propose tcgsaseq, a method to analyze RNA-seq data at the gene-set level, with a particular focus on longitudinal studies. We derive a variance component score test, similar to those that have been proposed in other testing situations (Wu and others, 2011; Huang and Lin, 2013), that facilitates testing both homogeneous and heterogeneous gene sets simultaneously. Variance component tests offer the speed and simplicity of standard score tests, but potentially gain statistical power by using many fewer degrees of freedom, and have been shown to have locally optimal power in some situations (Goeman and others, 2006). Inspired by the voom approach from Law and others (2014), we propose to estimate the mean-variance relationship in a more principled way using local linear regression, to account for the inherent heteroscedasticity of the data. Despite this nonparametric step, we demonstrate that the test statistic has a simple limiting distribution that is valid regardless of any model specification. We also propose a permutation version of the test to deal with small sample sizes. Our method is implemented in the R package tcgsaseq, available on the Comprehensive R Archive Network at % https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/tcgsaseq.

Our general approach to GSA in longitudinal RNA-seq studies has three primary advantages over existing approaches. First, unlike ROAST, our variance component approach remains valid under model misspecification and does not rely on ad hoc aggregation of information across genes. Second, unlike previous approaches to variance component testing in microarray data (Huang and Lin, 2013), our approach can accommodate the intrinsic mean-variance relationship in RNA-seq data, while remaining fast to compute. Third, our test remains powerful even when patients display heterogeneous trajectories over time.

The remainder of the article is organized as follows: Section 2 describes our variance component score test, while its asymptotic properties are derived in Section 3, and an estimation strategy and practical recommendations are detailed in Section 4. In Section 5, we present numerical studies assessing the potential impact of ignoring the mean-variance relationship in RNA-seq data, and comparing our approach to state-of-the-art methods of GSA. In Section 6, we apply tcgsaseq to the analysis of real data. Final remarks and comments are discussed in Section 7.

2. Variance component score test for longitudinal GSA

2.1 Problem setup

Consider  a vector of sequence read counts for subject

a vector of sequence read counts for subject  , that have been mapped to each of

, that have been mapped to each of  genes measured at times

genes measured at times  . Meanwhile,

. Meanwhile,  is a vector of baseline covariates describing experiment design conditions, all measured on individual

is a vector of baseline covariates describing experiment design conditions, all measured on individual  . So the full data considered for analysis are

. So the full data considered for analysis are  independent realizations from random vectors

independent realizations from random vectors  . Typically, the counts

. Typically, the counts  are normalized in some way in a preprocessing step (Hansen and others, 2012). We take

are normalized in some way in a preprocessing step (Hansen and others, 2012). We take  to be a normalized version of

to be a normalized version of  . For example, one standard normalization procedure accounts for the library size

. For example, one standard normalization procedure accounts for the library size  by computing the log-counts per million as

by computing the log-counts per million as

| (2.1) |

Based on these data, our interest is in identifying gene sets that have longitudinally changing expression patterns. The rest of this section will develop the proposed test statistic and its limiting distribution.

2.2 The test statistic

We are interested in testing for longitudinal changes in a pre-specified gene set, which for the purposes of illustration we take to be the first  genes,

genes,  . To develop a variance component score test statistic, we start from the following working model, which is a linear mixed effect model (Laird and Ware, 1982; Fitzmaurice and others, 2012)

. To develop a variance component score test statistic, we start from the following working model, which is a linear mixed effect model (Laird and Ware, 1982; Fitzmaurice and others, 2012)

| (2.2) |

and which can be rewritten as

| (2.3) |

where  is a

is a  vector of gene-specific intercepts

vector of gene-specific intercepts  ,

,  is a

is a  vector of random intercepts

vector of random intercepts  ,

,  is a

is a  block diagonal matrix with each block consisting of

block diagonal matrix with each block consisting of  rows equal to the fixed effect baseline covariates

rows equal to the fixed effect baseline covariates  ,

,  is a

is a  vector of gene-specific fixed effects

vector of gene-specific fixed effects  ,

,  is a

is a  block-diagonal matrix encoding the effect of time with each block having

block-diagonal matrix encoding the effect of time with each block having  row

row  for some set of

for some set of  basis functions

basis functions  ,

,  is a

is a  vector of gene-specific fixed effects of time

vector of gene-specific fixed effects of time  ,

,  is a

is a  vector of gene-specific individual-level effects of time, and

vector of gene-specific individual-level effects of time, and  is a

is a  covariance matrix of measurement errors. Note that

covariance matrix of measurement errors. Note that  is indexed by

is indexed by  and may depend on the mean of

and may depend on the mean of  . We assume that

. We assume that  . It is important to note that, in practice, the above model is unlikely to hold. Fortunately, the testing procedure we propose is entirely robust to its misspecification.

. It is important to note that, in practice, the above model is unlikely to hold. Fortunately, the testing procedure we propose is entirely robust to its misspecification.

We are interested in testing the null hypothesis of no longitudinal change in the normalized gene expression for any genes in the gene set

| (2.4) |

or, that is,  . Under the model (2.3), the null hypothesis (2.4) corresponds to the following null:

. Under the model (2.3), the null hypothesis (2.4) corresponds to the following null:  , which tests for both homogeneous and heterogeneous dynamics within the gene sets. In section 3, we demonstrate that the corresponding variance component score test can be written as

, which tests for both homogeneous and heterogeneous dynamics within the gene sets. In section 3, we demonstrate that the corresponding variance component score test can be written as

| (2.5) |

where  ,

,  ,

,  is a working covariance matrix defined in (3.2), and

is a working covariance matrix defined in (3.2), and  is the symmetric half matrix such that

is the symmetric half matrix such that  . We also show in the supplementary material available at Biostatistics online that given the dimension of

. We also show in the supplementary material available at Biostatistics online that given the dimension of  (

( ) is small relative to the number of individuals (

) is small relative to the number of individuals ( ), the asymptotic distribution of the test statistic is a mixture of

), the asymptotic distribution of the test statistic is a mixture of  random variables,

random variables,  where the mixing coefficients

where the mixing coefficients  depend on the covariance of

depend on the covariance of  . This asymptotic distribution holds regardless of the distribution of

. This asymptotic distribution holds regardless of the distribution of  .

.

In the end, p-values may be computed by comparing the observed test statistic  to the distribution of

to the distribution of  where

where  is an estimate of

is an estimate of  . Details are developed further in Section 3 and the supplementary material available at Biostatistics online. When the entries of

. Details are developed further in Section 3 and the supplementary material available at Biostatistics online. When the entries of  are correlated—that is, there is correlation between genes in the gene set—then the degrees of freedom for the test based on

are correlated—that is, there is correlation between genes in the gene set—then the degrees of freedom for the test based on  may be much lower than the degrees of freedom for a similar Wald or score test, yielding more power to detect departures from the null hypothesis.

may be much lower than the degrees of freedom for a similar Wald or score test, yielding more power to detect departures from the null hypothesis.

In practice, the parameters  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  are unknown and must be estimated. In particular, accounting for the mean-variance relationship encoded in

are unknown and must be estimated. In particular, accounting for the mean-variance relationship encoded in  is vital in RNA-seq data. Hence we estimate the test statistic as

is vital in RNA-seq data. Hence we estimate the test statistic as

| (2.6) |

and we further demonstrate in section 3 that plugging in standard estimates of  ,

,  , and

, and  and a nonparametric estimator of

and a nonparametric estimator of  for the estimated test statistic still yields a similar asymptotic distribution:

for the estimated test statistic still yields a similar asymptotic distribution:

| (2.7) |

for mixing coefficients  given in the supplementary material available at Biostatistics online.

given in the supplementary material available at Biostatistics online.

The strength of our approach is that this simple limiting distribution holds even when the model (2.3) may be misspecified and despite the presence of the nonparametric estimator of  in (2.6). In this way, we may account very flexibly for the mean-variance relationship in

in (2.6). In this way, we may account very flexibly for the mean-variance relationship in  while maintaining a simple, powerful test statistic that does not require any particular model to hold.

while maintaining a simple, powerful test statistic that does not require any particular model to hold.

The convergence in (2.7) relies on the central limit theorem. There may of course be situations where the central limit theorem fails to kick in, either when the number of genes in the gene set  is quite large, or else when the number of individuals

is quite large, or else when the number of individuals  is small. We now discuss two modifications for these scenarios.

is small. We now discuss two modifications for these scenarios.

2.2.1 Testing for homogeneous gene sets.

When the number of genes  is large relative to

is large relative to  , the convergence of

, the convergence of  to a limiting normal distribution may be in doubt. In these cases, it might be better to begin from a working model that assumes that all genes share a common trajectory over time as a useful approximation. To wit, we may reduce the number of parameters in the model by taking

to a limiting normal distribution may be in doubt. In these cases, it might be better to begin from a working model that assumes that all genes share a common trajectory over time as a useful approximation. To wit, we may reduce the number of parameters in the model by taking  in model (2.3) to be a

in model (2.3) to be a  counterpart of

counterpart of  , and similarly

, and similarly  to be

to be  ,

,  to be

to be  , and

, and  to be

to be  counterparts, respectively, of the original quantities. The derivation of the test statistic follows precisely the same lines with updated dimensions.

counterparts, respectively, of the original quantities. The derivation of the test statistic follows precisely the same lines with updated dimensions.

2.2.2 Using permutation.

When  is very small (or alternatively when

is very small (or alternatively when  is relatively large but the homogeneous strategy described above seems unwise), relying on the limiting distribution (2.7) may not be accurate. In these cases, permutation may be used to estimate the empirical distribution of

is relatively large but the homogeneous strategy described above seems unwise), relying on the limiting distribution (2.7) may not be accurate. In these cases, permutation may be used to estimate the empirical distribution of  under the null (2.4). To perform the permutations, we simply shuffle the time labels within each individual to get permuted observations for the

under the null (2.4). To perform the permutations, we simply shuffle the time labels within each individual to get permuted observations for the  th individual

th individual  , where

, where  is a permutation of

is a permutation of  . Indeed, under the null, observations of a given gene

. Indeed, under the null, observations of a given gene  for a given individual

for a given individual  are exchangeable, regardless of sampling time. A large number

are exchangeable, regardless of sampling time. A large number  of permutation-based test statistics

of permutation-based test statistics  can thus be generated where each

can thus be generated where each  is computed using the

is computed using the  th set of permuted data. p-values may then be computed as

th set of permuted data. p-values may then be computed as

3. Properties of the test statistic

In this section, we derive the test statistic and demonstrate its asymptotic distribution assuming all parameters known. We then take up the distribution of the test statistic when estimating all relevant parameters.

3.1 Test statistic derivation

Under the working model (2.3),  Integrating over the random intercepts

Integrating over the random intercepts  , we can rewrite the model as

, we can rewrite the model as

| (3.1) |

where  denotes time-independent fixed effects,

denotes time-independent fixed effects,  denotes combined effects of time.

denotes combined effects of time.

The test for no longitudinal changes in expression corresponds to the model-based hypothesis  . We write

. We write  as

as  and we consider the working assumption that the

and we consider the working assumption that the  are independently distributed such that

are independently distributed such that  (under the null) and

(under the null) and

| (3.2) |

Under this working assumption,  is equivalent to

is equivalent to  . To obtain the variance component test statistic, rewrite the model as:

. To obtain the variance component test statistic, rewrite the model as:  for centered outcome

for centered outcome  . Then

. Then  and the log-likelihood for

and the log-likelihood for  can be written as

can be written as

| (3.3) |

Because the target of inference is  , we marginalize over the nuisance parameter

, we marginalize over the nuisance parameter  conditional on the observed data to obtain

conditional on the observed data to obtain  where the expectation is taken over the distribution of

where the expectation is taken over the distribution of  . We follow the argument in Commenges and Andersen (1995) and note that the score at the null value is 0:

. We follow the argument in Commenges and Andersen (1995) and note that the score at the null value is 0:  . So we instead consider the score with respect to

. So we instead consider the score with respect to  , which is equal to

, which is equal to

| (3.4) |

| (3.5) |

Thus, after normalizing by  , the variance component score test statistic can be written

, the variance component score test statistic can be written  , as described in (2.5). If the dimension of

, as described in (2.5). If the dimension of  is small relative to the sample size,

is small relative to the sample size,  is asymptotically normal by the central limit theorem, which means that the limiting distribution of

is asymptotically normal by the central limit theorem, which means that the limiting distribution of  is a mixture of

is a mixture of  s (see supplementary material available at Biostatistics online for more details).

s (see supplementary material available at Biostatistics online for more details).

3.2 Estimated test statistic limiting distribution

In practice, estimates need to be supplied for many of the quantities in the test statistic to be estimated in (2.6). Following the argument for the limiting distribution of  ,

,  has a limiting distribution of a mixture of

has a limiting distribution of a mixture of  s so long as

s so long as  has a limiting normal distribution. To establish this, we define

has a limiting normal distribution. To establish this, we define  to be a version of

to be a version of  where

where  is replaced with its limit,

is replaced with its limit,  . The quantities

. The quantities  and

and  are asymptotically equivalent, and the central limit theorem ensures that

are asymptotically equivalent, and the central limit theorem ensures that  has a limiting normal distribution. Therefore, the asymptotic distribution of

has a limiting normal distribution. Therefore, the asymptotic distribution of  is a mixture of

is a mixture of  s (see supplementary material available at Biostatistics online for details), and the corresponding testing procedure is valid under any data-generating function and robust to misspecification of the working model 2.3.

s (see supplementary material available at Biostatistics online for details), and the corresponding testing procedure is valid under any data-generating function and robust to misspecification of the working model 2.3.

4. Estimation

The test statistic (2.6) contains the estimated quantities  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  . In this section, we take up practical issues involved in the estimation of these quantities.

. In this section, we take up practical issues involved in the estimation of these quantities.

4.1. Estimating model parameters

In this section, we will discuss estimation of  , assuming that we have a consistent estimator of

, assuming that we have a consistent estimator of  in hand (we leave discussion of estimating

in hand (we leave discussion of estimating  to the following section). A natural way to estimate

to the following section). A natural way to estimate  , taking into account the heteroscedasticity in

, taking into account the heteroscedasticity in  , is to fit a weighted mixed effects model corresponding to

, is to fit a weighted mixed effects model corresponding to

| (4.1) |

where the random intercepts  have been integrated out and

have been integrated out and  is taken to be

is taken to be  . The weights are taken to be

. The weights are taken to be  . This model corresponds to the model (3.1).

. This model corresponds to the model (3.1).

In practice, fitting the full mixed effects model for each of many gene sets may be computationally demanding. In these cases, the simpler fixed effects model

| (4.2) |

may be fit to estimate  and

and  .

.  may not be estimated directly from (4.2). In this case, it may be specified using a working estimate or taken to be the identity matrix.

may not be estimated directly from (4.2). In this case, it may be specified using a working estimate or taken to be the identity matrix.

4.2. Estimating the mean-variance relationship

One key feature of our approach is to estimate  in such a way as to account for the heteroscedasticity in

in such a way as to account for the heteroscedasticity in  . It is important to note that accurate estimation of

. It is important to note that accurate estimation of  will likely increase power but will not affect the validity or type I error of the testing procedure.

will likely increase power but will not affect the validity or type I error of the testing procedure.

To approximate the mean-variance relationship in  , we use information from all

, we use information from all  genes. We assume that the diagonal elements of

genes. We assume that the diagonal elements of  , which we will denote

, which we will denote  , may be modelled as a function of their means

, may be modelled as a function of their means  . Specifically,

. Specifically,  for some unknown function

for some unknown function  and errors which follow the moment conditions

and errors which follow the moment conditions  .

.

We follow Law and others (2014) in using local linear regression in estimating  . We will first write out the form of the estimator if all parameters were known:

. We will first write out the form of the estimator if all parameters were known:  , where

, where  for some kernel function

for some kernel function  and bandwidth

and bandwidth  .

.

The means  and variances

and variances  could in principle be estimated using some parametric model like (4.1) for all

could in principle be estimated using some parametric model like (4.1) for all  genes. Let

genes. Let  denote the estimated mean and variance for

denote the estimated mean and variance for  . Then the mean-variance relationship may be estimated as

. Then the mean-variance relationship may be estimated as

| (4.3) |

As with any smoothing procedure, choice of the bandwidth  is paramount in producing a reliable estimator. Standard cross-validation techniques may be used to select

is paramount in producing a reliable estimator. Standard cross-validation techniques may be used to select  in practice. Then the diagonal entries of

in practice. Then the diagonal entries of  can be estimated as

can be estimated as  .

.

Practical considerations. Under the model (4.1), we could take  and

and  . However, because

. However, because  , fitting (4.1) for such a large number of genes is not practical. Instead, the simpler model (4.2) could be used. Then

, fitting (4.1) for such a large number of genes is not practical. Instead, the simpler model (4.2) could be used. Then  could be taken to be

could be taken to be  and

and  to be

to be  to be

to be  . A similar approach was used to model heteroscedasticity in the context of linear regression in Carroll (1982).

. A similar approach was used to model heteroscedasticity in the context of linear regression in Carroll (1982).

On the other hand, fitting a local linear regression on all of  and

and  – a total of

– a total of  observations – may be computationally difficult. In order to reduce the number of points used in the nonparametric fit (4.3), one could follow Law and others (2014) and model the mean-variance relationship at the gene level

observations – may be computationally difficult. In order to reduce the number of points used in the nonparametric fit (4.3), one could follow Law and others (2014) and model the mean-variance relationship at the gene level

| (4.4) |

The gene-level mean may be estimated as  and the gene-level variance as

and the gene-level variance as  .

.

5. Numerical study

In this numerical study section, we illustrate both the importance of accounting for RNA-seq data’s heteroscedasticity and the superiority of tcgsaseq in terms of statistical power and robustness. We have performed simulations under two different settings. The first one demonstrates the good behavior of the asymptotic test under various scenarios in synthetic data. The second one focuses on a very realistic situation where sample size is small and gene counts are generated from a distribution of real observed RNA-seq data. Throughout, for the purposes of testing, we take  and

and  to be the identity for simplicity. In practice, more precise estimation of

to be the identity for simplicity. In practice, more precise estimation of  and

and  would serve to increase power. Finally, throughout we use Davies’s approximation method (Davies, 1980) to compute p-values for the mixture of

would serve to increase power. Finally, throughout we use Davies’s approximation method (Davies, 1980) to compute p-values for the mixture of  s, implemented in the CompQuadForm R package (Duchesne and Lafaye De Micheaux, 2010).

s, implemented in the CompQuadForm R package (Duchesne and Lafaye De Micheaux, 2010).

5.1. Synthetic data

In this subsection, we use synthetic data to illustrate the behavior of our estimator when the distribution of the data is known. We first look at the importance of accounting for the mean-variance relationship in  in tcgsaseq, and then we compare tcgsaseq to other competing methods, including ROAST, edgeR-ROAST, and DESeq2. In order to adapt DESeq2 to self-contained gene set testing, we use the minimum P-value test to adequately combine univariate p-values for testing a whole gene set while taking into account gene correlation (Lin and others, 2011) and we refer to it as DESeq2-min test. We demonstrate that the tcgsaseq testing procedure is robust to even heavy misspecification of the mean model and the mean-variance relationship, while ROAST, edgeR-ROAST and DESeq2-min test may suffer from extreme lack of power compared to tcgsaseq or inflate type I errors under misspecification.

in tcgsaseq, and then we compare tcgsaseq to other competing methods, including ROAST, edgeR-ROAST, and DESeq2. In order to adapt DESeq2 to self-contained gene set testing, we use the minimum P-value test to adequately combine univariate p-values for testing a whole gene set while taking into account gene correlation (Lin and others, 2011) and we refer to it as DESeq2-min test. We demonstrate that the tcgsaseq testing procedure is robust to even heavy misspecification of the mean model and the mean-variance relationship, while ROAST, edgeR-ROAST and DESeq2-min test may suffer from extreme lack of power compared to tcgsaseq or inflate type I errors under misspecification.

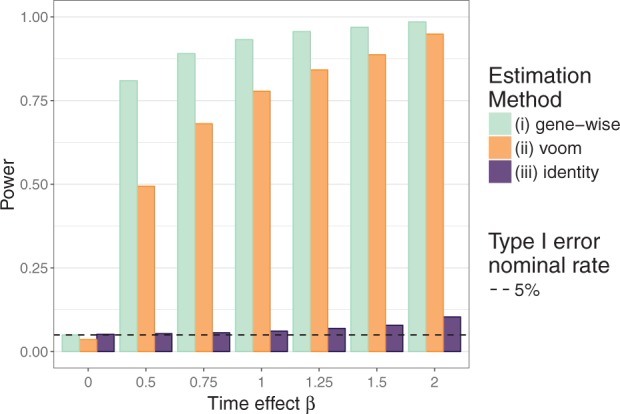

5.1.1. Mean-variance relationship

To illustrate the importance of estimating the mean-variance relationship, we generated data under the model  where

where

| (5.1) |

with  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  . We set

. We set  and

and  was allowed to be set to 6 different values within a range from

was allowed to be set to 6 different values within a range from  to

to  :

:  . We considered three methods of accounting for the mean-variance relationship: (i) gene-level estimates using equation (4.4); (ii) voom-type estimation Law and others (2014); (iii) specifying

. We considered three methods of accounting for the mean-variance relationship: (i) gene-level estimates using equation (4.4); (ii) voom-type estimation Law and others (2014); (iii) specifying  to be the identity. Throughout this section, we test at the

to be the identity. Throughout this section, we test at the  level. The model (4.2) was used to generate the test statistic and adjust for covariates, and the gene-level equation (4.4) was used to estimate the mean-variance relationship. Note that the mean model (4.2) is misspecified.

level. The model (4.2) was used to generate the test statistic and adjust for covariates, and the gene-level equation (4.4) was used to estimate the mean-variance relationship. Note that the mean model (4.2) is misspecified.

When applying our variance component test, type I error was at the nominal level using either strategy (i) or (iii), but was deflated to 0.035 when using strategy (ii). On the other hand, ROAST, which similarly relies on estimating the mean-variance relationship, inflated type I error to 0.56 when using (ii), and had adequate type I errors using the other weighting strategies. Such results indicate that ROAST may drastically inflate type I error rates in some cases, and that using (ii), the voom-type estimator, to account for heteroscedasticity led to worse performance in general.

Figure 1 demonstrates the effect of accounting for heteroscedasticity under the alternative hypothesis. The more accurate modeling of the mean-variance relationship with method (i) yields large power gains over method (ii). Conversely, by drastically mis-modelling the mean-variance relationship, the naive method (iii) yields almost no power for detecting longitudinal changes.

Fig. 1.

Power evaluation in synthetic data according to how heteroscedasticity is accounted for, based on 1000 simulations.

5.2. Comparison to competing methods

In this subsection, we compare tcgsaseq to ROAST, edgeR-ROAST, and DESeq2-min test using a highly misspecified model and using a negative binomial model. For the misspecified model, we again generate data under model (5.1) with one modification to ensure that the data are positive integers  . We set

. We set  and

and  , and

, and  took values between

took values between  2 and 2. Because DESeq2 is computationally intractable at higher sample sizes with large

2 and 2. Because DESeq2 is computationally intractable at higher sample sizes with large  , we set the total number of genes

, we set the total number of genes  to be 100. We used model (4.4) to compute the mean-variance relationship for both tcgsaseq and ROAST. Gene-based estimates were used for dispersions in DESeq2, and likelihood ratio tests were used to produce test statistics for both edgeR and DESeq2.

to be 100. We used model (4.4) to compute the mean-variance relationship for both tcgsaseq and ROAST. Gene-based estimates were used for dispersions in DESeq2, and likelihood ratio tests were used to produce test statistics for both edgeR and DESeq2.

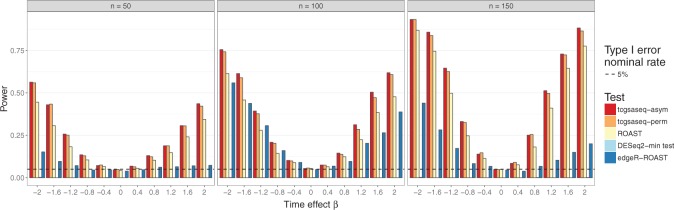

The results are depicted in Figure 2. We see that tcgsaseq has the highest power at all sample sizes and at all values of  . Though the model is highly misspecified for all methods, the negative-binomial-based methods edgeR-ROAST and DESeq2-min test suffer greatly in terms of power, in particular DESeq2-min test. In Figure 2, we show ROAST using the mean-variance relationship estimated from model (4.4), but it’s important to note that if the voom-type strategy were used, the type I error for ROAST rises to more than 0.1 at all sample sizes. Asymmetrical power curves around the null are expected for both edgeR and DESeq2 as they both assume the data have a negative binomial distribution (which is asymmetric with a heavier right tail).

. Though the model is highly misspecified for all methods, the negative-binomial-based methods edgeR-ROAST and DESeq2-min test suffer greatly in terms of power, in particular DESeq2-min test. In Figure 2, we show ROAST using the mean-variance relationship estimated from model (4.4), but it’s important to note that if the voom-type strategy were used, the type I error for ROAST rises to more than 0.1 at all sample sizes. Asymmetrical power curves around the null are expected for both edgeR and DESeq2 as they both assume the data have a negative binomial distribution (which is asymmetric with a heavier right tail).

Fig. 2.

Power evaluation in synthetic data comparing tcgsaseq, ROAST, edgeR-ROAST, and DESeq2-min test, based on 1000 simulations.

Secondly, we generated data under the negative binomial model, a distributional assumption that edgeR and DESeq2 make. The mean of the negative binomial was specified as  where

where  exponential(1/10),

exponential(1/10),  ,

,  , and the negative binomial dispersion parameter was set to 1. We again let

, and the negative binomial dispersion parameter was set to 1. We again let  vary between

vary between  2 and 2 and considered sample sizes of

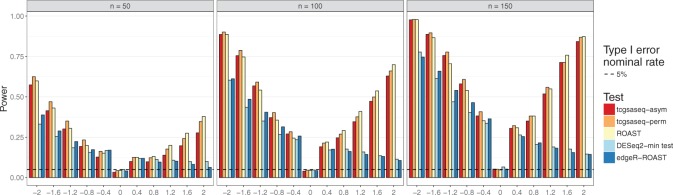

2 and 2 and considered sample sizes of  . In this setting, the default procedure to estimate dispersions was used for DESeq2. The results depicted in Figure 3 show that tcgsaseq and ROAST outperform edgeR-ROAST and DESeq2-min test despite the fact that the distributional assumptions of edgeR and DESeq2 are true. The performance of tcgsaseq and ROAST is in general comparable. Furthermore, it is important to highlight that DESeq2-min test does not control the type I error, and the type I error gets worse as sample size increases.

. In this setting, the default procedure to estimate dispersions was used for DESeq2. The results depicted in Figure 3 show that tcgsaseq and ROAST outperform edgeR-ROAST and DESeq2-min test despite the fact that the distributional assumptions of edgeR and DESeq2 are true. The performance of tcgsaseq and ROAST is in general comparable. Furthermore, it is important to highlight that DESeq2-min test does not control the type I error, and the type I error gets worse as sample size increases.

Fig. 3.

Power evaluation in negative binomial data comparing tcgsaseq, ROAST, edgeR-ROAST, and DESeq2-min test, based on 1000 simulations.

5.3. Realistic small samples simulations

In this subsection, we simulated another dataset to illustrate the good behavior of the tcgsaseq permutation test in the realistic setting of a small sample size. We generated data for 6 individuals each measured at 3 time points according to the scenario described in Law and others (2014), using the script provided in their supplementary material:  and

and  where

where  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  follows an empirical baseline distribution derived from real RNA-seq counts data, provided in supplementary material of Law and others (2014). This simulation scheme allows us to generate data that realistically resemble real RNA-seq count data. We set

follows an empirical baseline distribution derived from real RNA-seq counts data, provided in supplementary material of Law and others (2014). This simulation scheme allows us to generate data that realistically resemble real RNA-seq count data. We set  with

with  , and gene sets were constructed such that

, and gene sets were constructed such that  and for every gene pair

and for every gene pair  in the set

in the set  .

.  was allowed to be set to 8 different values within a range from

was allowed to be set to 8 different values within a range from  to

to  :

:  .

.

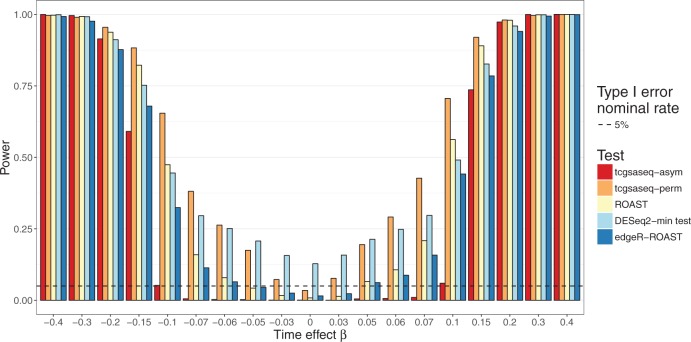

As shown in Figure 4, under this setting, edgeR-ROAST, ROAST, and the proposed permutation test all control the type I error at nominal rate. However, DESeq2-min test fails to control the type I error, while it is highly deflated for the asymptotic version of tcgsaseq (0.001) which is not surprising given that with such a small sample size it is unlikely the central limit theorem would have come into effect yet. Nonetheless, we observe a steady and consistent increase of power for our method using the permutation test over the compared state-of-the-art approaches. The deviation from the negative binomial distribution hypothesis (which both edgeR and DESeq2 rely upon), as well as the univariate gene-wise step first needed, explain those poor performances compared to tcgsaseq. Similar results are obtained when adding a random effect of time simulating heterogeneous gene sets (see supplementary material available at Biostatistics online). In addition, as gene sets were constructed with correlated genes, these results also indicates that tcgsaseq is robust to and can take advantage of inter-gene correlation.

Fig. 4.

Power evaluation in realistically simulated data with a small sample size, based on 500 simulations.

6. Application to two real datasets

In this section, we present analyses of two real datasets. In both analyses,  and

and  were again taken as the identity while

were again taken as the identity while  was estimated at the gene level using equation (4.4) for tcgsaseq. The ROAST method was applied in combination with precision weights estimated through the voom approach. Given the sample sizes available in both studies, we used the tcgsaseq permutation test. In both cases, only transformed data were available and not original counts data, preventing us from applying either edgeR-ROAST or DESeq2-min test.

was estimated at the gene level using equation (4.4) for tcgsaseq. The ROAST method was applied in combination with precision weights estimated through the voom approach. Given the sample sizes available in both studies, we used the tcgsaseq permutation test. In both cases, only transformed data were available and not original counts data, preventing us from applying either edgeR-ROAST or DESeq2-min test.

6.1. Longitudinal RNA-seq measurements in successful kidney transplant patients

We analyzed a RNA-seq dataset from Dorr and others (2015), in which gene expression was measured in the peripheral blood mononuclear cells of 32 kidney transplant patients. Gene expression was measured at 4 time points: before transplantation, 1 week after transplantation, 3 months after transplantation and 6 months after transplantation. The patients had no graft rejection at the time of each sample.

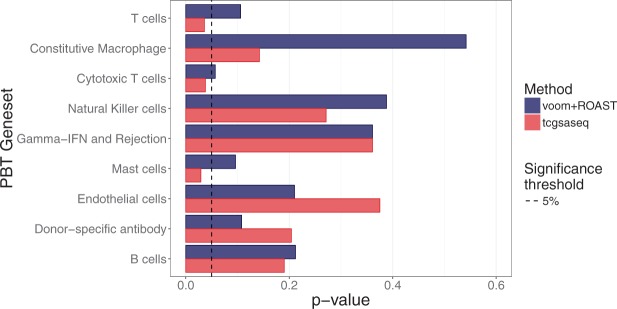

We investigated custom gene sets targeted specifically towards kidney transplant. Those kidney-oriented gene sets were derived by the Alberta Transplant Applied Genomics Center from specific pathogenesis-based transcripts (Halloran and others, 2010), and their definition is available at http://atagc.med.ualberta.ca/Research/GeneLists. We tested for a linear change in gene expression over time while adjusting for patient’s age and gender.

Figure 5 shows the p-values for those 9 gene sets for both tcgsaseq and ROAST. At a 5% threshold, our approach tcgsaseq identifies three significant gene sets while the combination of voom and ROAST identifies none. Among those significant gene sets, two relate to T-cell gene expression, corroborating the original results from Dorr and others (2015). The gene set annotated as “T-cells” notably includes the gene CD3D, previously highlighted in Dorr and others (2015). On the other hand, gene sets related to transplant rejection such as “Donor-specific antibody” or “Gamma-IFN and Rejection” have much higher p-values here, which is what one would expect as these data include only successful transplant patients. Besides, tcgsaseq also detects a significant change in expression for the gene set related to Mast cells, which have recently been highlighted as playing an ambiguous role in kidney transplant (Papadimitriou and others, 2013). Mast cells have been linked both to peripheral tolerance (de Vries and others, 2009), as well as to late graft loss (Jevnikar and Mannon, 2008). These results both reinforce and broaden the original findings from Dorr and others (2015).

Fig. 5.

p-values from testing the 9 kidney oriented gene sets investigated.

6.2. Time-course RNA-seq comparative study of Arabidopsis arenosa physiology

In a recent experiment, Baduel and others (2016) measured time-course gene expression of the plant Arabidopsis arenosa through RNA-seq. They sampled 48 plants across 13 weeks at four different time points. Baduel and others (2016) were especially interested in the difference between two populations of Arabidopsis arenosa, respectively denoted KA and TBG, that have adopted different flowering strategies. In addition, half of the plants were exposed to cold and short day photoperiods (vernalization) between week 4 and week 10 in order to study the corresponding effect on flowering in both populations. Different plant siblings were sampled at each time point in order to avoid the important stress effect of leaf removal on the plants.

Dealing with this complex experiment design, we used tcgsaseq to address two separate biological questions: (i) which gene sets have a different activation between the two populations, adjusted for the plant age and the cold exposure, (ii) which gene sets have a different activation due to cold exposure, adjusted for population differences and plant age. Using two different modeling strategies, we found that one data-driven gene set constructed by Baduel and others (2016) from the top 1% differentially expressed genes between the two populations was significant at a 5% threshold for (i) and for (ii). On the contrary two other data-driven gene sets, again constructed by Baduel and others (2016) and identified as the respective population-specific responses to cold exposure, were both significant at this 5% threshold for (ii) but not for (i). In addition, two gene sets from Gene Ontology associated with salt and cold response pathways, respectively, were also investigated and found significant at the 5% level for (ii) but not for (i). In comparison, ROAST gave similar results for (i), but lacked power for (ii) identifying only 1 out of 4 significant gene sets. This analysis corroborates the results obtained by Baduel and others (2016), and it further illustrates the good behavior of tcgsaseq in complex time-course RNA-seq studies.

7. Discussion

The proposed method detailed in this article constitutes an innovative and flexible approach for performing GSA of longitudinal RNA-seq gene expression measurements. The approach relies on a principled variance component score test that accounts for the intrinsic heteroscedasticity of RNA-seq data, and for which we derive a simple limiting distribution without requiring any particular model to hold. As illustrated in the previous sections, the good performance of the method when applied to various datasets constitutes a major strength of the method.

Our numerical study shows the importance of accurately accounting for heteroscedasticity when analyzing RNA-seq data. We also demonstrate the robustness of our testing procedure to model misspecification. When comparing our proposed approach to ROAST, edgeR, and DESeq2, state-of-the-art methods, we illustrate the competing methods’ sensitivity to model misspecification, failure to control Type I error, and reduced statistical power compared to tcgsaseq.

Of particular biological interest in longitudinal studies, the proposed approach can test for both homogeneous and heterogeneous gene sets simultaneously. This is especially relevant for gene sets constructed from biological pathways encompassing both regulators and targets, where different expression dynamics are expected across genes. In addition, the proposed solution for accounting for heteroscedasticity can also deal with non-count data and could in principle be applied widely.

As demonstrated by the simulation studies, the proposed approach is also robust to inter-gene correlation within tested gene sets. While in our simulations we do not estimate inter-gene correlations, one could account for them more formally by following Wang and others (2009) and estimating a working correlation matrix with the residuals from an initial gene-wise modelling of  . The resulting estimates could be incorporated into the structure of

. The resulting estimates could be incorporated into the structure of  to increase power.

to increase power.

This work features 4 important novelties: (i) we propose a statistically sound nonparametric estimation of the inherent mean-variance relationship in RNA-seq data; (ii) we present an original variance component score test statistic for which we derive an asymptotic distribution, and we show that it possesses the conventional root- convergence rate despite the presence of a nonparametric estimator and is robust to model misspecification; (iii) we conduct a numerical study comparing the proposed method and illustrating its good statistical performances under various settings; (iv) we provide an implementation of the proposed method as an R package available to the community.

convergence rate despite the presence of a nonparametric estimator and is robust to model misspecification; (iii) we conduct a numerical study comparing the proposed method and illustrating its good statistical performances under various settings; (iv) we provide an implementation of the proposed method as an R package available to the community.

These innovations contrast with previous works from either Law and others (2014) or Hejblum and others (2015). While the nonparametric estimation of heteroscedasticity from Law and others (2014) is more of a heuristic procedure, our statistically rigorous approach does not include unmotivated transformations or extrapolation outside the range of the estimating function. Furthermore, we show that our test statistic has the conventional root- rate despite the presence of the nonparametric estimator. As for Hejblum and others (2015), they focus exclusively on microarray data and therefore completely ignore the heteroscedasticity issue. In addition, while the modeling proposed in this article is similar to theirs, our test statistic is completely different. While they rely on a likelihood ratio test, we propose an original variance component score test that remains valid even if the model was misspecified and is very fast to compute.

rate despite the presence of the nonparametric estimator. As for Hejblum and others (2015), they focus exclusively on microarray data and therefore completely ignore the heteroscedasticity issue. In addition, while the modeling proposed in this article is similar to theirs, our test statistic is completely different. While they rely on a likelihood ratio test, we propose an original variance component score test that remains valid even if the model was misspecified and is very fast to compute.

Finally, in this article, we focus primarily on longitudinal measurements of RNA-seq. However, our approach directly applies to virtually all RNA-seq study designs, including traditional case-control and more complex studies. Our approach allows researchers to incorporate the natural heteroscedasticity in the data into a powerful test statistic that makes no modeling assumptions. Of note, the inclusion of time-varying covariates would require further assumptions concerning the model to be made to ensure the limiting distribution of the test statistic. Evaluating tcgsaseq’s performance in a broader array of studies is an area for future research.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors express their deepest gratitude to Professor Tianxi Cai, Harvard University, for her help and support in this work. They also thank Pierre Baduel for his help in analyzing the plant physiology data.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Software

Software is available on the Comprehensive R Archive Network as an R package tcgsaseq.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at http://biostatistics.oxfordjournals.org.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) [U54 HG007963 to B.P.H.].

References

- Ackermann, M. and Strimmer, K. (2009). A general modular framework for gene set enrichment analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 10, 47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anders, S. and Huber, W. (2010). Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biology 11, R106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baduel, P., Arnold, B., Weisman, C. M., Hunter, B. and Bomblies, K.. (2016). Habitat-associated life history and stress-tolerance variation in Arabidopsis arenosa. Plant Physiology 171, 437–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, R. J. (1982). Adapting for heteroscedasticity in linear models. The Annals of Statistics 10, 1224–1233. [Google Scholar]

- Commenges, D. and Andersen, P. K. (1995). Score test of homogeneity for survival data. Lifetime Data Analysis 1, 145–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui, S., Ji, T. Li, J., Cheng, J. and Qiu, J. (2016). What if we ignore the random effects when analyzing RNA-seq data in a multifactor experiment. Statistical Applications in Genetics and Molecular Biology 15(2), 87–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies, R. B. (1980). Algorithm AS 155: the distribution of a linear combination of chi-2 random variables. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series C (Applied Statistics) 29, 323–333. [Google Scholar]

- de Vries, V. C., Pino-Lagos, K., Elgueta, R. and Noelle, R. J. (2009). The enigmatic role of mast cells in dominant tolerance. Current Opinion in Organ Transplantation 14, 332–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorr, C., Wu, B., Guan, W., Muthusamy, A., Sanghavi, K., Schladt, D. P., Maltzman, J. S., Scherer, S. E., Brott, M. J., Matas, A. J., Jacobson, P. A., Oetting, W. S.. and others (2015). Differentially expressed gene transcripts using RNA sequencing from the blood of immunosuppressed kidney allograft recipients. PLoS ONE 10, 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchesne, P. and Lafaye De Micheaux, P. (2010). Computing the distribution of quadratic forms: further comparisons between the Liu-Tang-Zhang approximation and exact methods. Computational Statistics and Data Analysis 54, 858–862. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzmaurice, G. M., Laird, N. M. and Ware, J. H. (2012). Applied longitudinal analysis, vol. 998 John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Goeman, J. J. and Büuhlmann, P. (2007). Analyzing gene expression data in terms of gene sets: methodological issues. Bioinformatics 23, 980–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goeman, J. J., van de Geer, S. A. and van Houwelingen, H. C. (2006). Testing against a high dimensional alternative. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Statistical Methodology) 68, 477–493. [Google Scholar]

- Halloran, P. F., De Freitas, D. G., Einecke, G., Famulski, K. S., Hidalgo, L. G., Mengel, M., Reeve, J., Sellares, J., and Sis, B. (2010). The molecular phenotype of kidney transplants: personal viewpoint. American Journal of Transplantation 10, 2215–2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, K. D., Irizarry, R. A. and Wu, Z. (2012). Removing technical variability in RNA-seq data using conditional quantile normalization. Biostatistics 13, 204–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hejblum, B. P., Skinner, J. and Thiébaut, R. (2015). Time-course gene set analysis for longitudinal gene expression data. PLOS Computational Biology 11, e1004310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y., Gao, L., Shi, K. and Chiu, D. K. Y. (2013). Detection of deregulated modules using deregulatory linked path. PloS One 8, e70412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y. T. and Lin, X. (2013). Gene set analysis using variance component tests. BMC Bioinformatics 14, 210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jevnikar, A. M. and Mannon, R. B. (2008). Late kidney allograft loss: what we know about it, and what we can do about it. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 3, 56–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird, N. M. and Ware, J. H. (1982). Random-effects models for longitudinal data. Biometrics 38, 963–974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law, C. W., Chen, Y., Shi, W. and Smyth, G. K. (2014). voom: precision weights unlock linear model analysis tools for RNA-seq read counts. Genome Biology 15, R29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, X., Cai, T., Wu, M. C., Zhou, Q., Liu, G., Christiani, D. C. and Lin, X. (2011). Kernel machine SNP-set analysis for censored survival outcomes in genome-wide association studies. Genetic Epidemiology 35, 620–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love, M. I, Huber, W. and Anders, S.(2014). Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biology 15, 550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marioni, J. C., Mason, C. E., Mane, S. M., Stephens, M. and Gilad, Y. (2008). RNA-seq: an assessment of technical reproducibility and comparison with gene expression arrays. Genome Research 18, 1509–1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, D. J., Chen, Y. and Smyth, G. K. (2012). Differential expression analysis of multifactor RNA-Seq experiments with respect to biological variation. Nucleic Acids Research 40, 4288–4297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nueda, M. J.é, Tarazona, S. and Conesa, A. (2014). Next maSigPro: updating maSigPro bioconductor package for RNA-seq time series. Bioinformatics 30, 2598–2602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadimitriou, J. C., Drachenberg, C. B., Ramos, E., Ugarte, R. and Haririan, A. (2013). Mast cell quantitation in renal transplant biopsy specimens as a potential marker for the cumulative burden of tissue injury. Transplantation Proceedings 45, 1469–1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahmatallah, Y., Emmert-Streib, F. and Glazko, G. (2016). Gene set analysis approaches for RNA-seq data: performance evaluation and application guideline. Briefings in Bioinformatics, 17, 393–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, M. D., McCarthy, D. J. and Smyth, G. K. (2010). edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26, 139–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian, A., Tamayo, P., Mootha, V. K., Mukherjee, S., Ebert, B. L., Gillette, M. A., Paulovich, A., Pomeroy, S. L., Golub, T. R., Lander, E. S. and Mesirov, J. P. (2005). Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102, 15545–15550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L., Chen, X., Wolfinger, R. D., Franklin, J. L., Coffey, R. J. and Zhang, B. (2009). A unified mixed effects model for gene set analysis of time course microarray experiments. Statistical Applications in Genetics and Molecular Biology 8, 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, D., Lim, E., Wu, D., Lim, E., Vaillant, F., Asselin-Labat, M.-L., Visvader, J. E. and Smyth, G. K. (2010). ROAST: rotation gene set tests for complex microarray experiments. Bioinformatics 26, 2176–2182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, M. C., Lee, S., Cai, T., Li, Y., Boehnke, M. and Lin, X. (2011). Rare-variant association testing for sequencing data with the sequence kernel association test. American Journal of Human Genetics 89, 82–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.