Summary

Epidemiological research supports an association between maternal exposure to air pollution during pregnancy and adverse children’s health outcomes. Advances in exposure assessment and statistics allow for estimation of both critical windows of vulnerability and exposure effect heterogeneity. Simultaneous estimation of windows of vulnerability and effect heterogeneity can be accomplished by fitting a distributed lag model (DLM) stratified by subgroup. However, this can provide an incomplete picture of how effects vary across subgroups because it does not allow for subgroups to have the same window but different within-window effects or to have different windows but the same within-window effect. Because the timing of some developmental processes are common across subpopulations of infants while for others the timing differs across subgroups, both scenarios are important to consider when evaluating health risks of prenatal exposures. We propose a new approach that partitions the DLM into a constrained functional predictor that estimates windows of vulnerability and a scalar effect representing the within-window effect directly. The proposed method allows for heterogeneity in only the window, only the within-window effect, or both. In a simulation study we show that a model assuming a shared component across groups results in lower bias and mean squared error for the estimated windows and effects when that component is in fact constant across groups. We apply the proposed method to estimate windows of vulnerability in the association between prenatal exposures to fine particulate matter and each of birth weight and asthma incidence, and estimate how these associations vary by sex and maternal obesity status in a Boston-area prospective pre-birth cohort study.

Keywords: Birth weight, Child asthma, Distributed lag models, Exposure effect heterogeneity, Fine particulate matter, Functional data analysis

1. Introduction

A growing body of research supports an association between maternal exposure to air pollution during pregnancy and a variety of birth and children’s health outcomes. Epidemiological studies have found that maternal exposure to ambient air pollution is associated with decreased birth weight as well as increased risk of preterm birth and respiratory disorders including asthma (Šrám and others, 2005; Kelly and Fussell, 2011; Shah and Balkhair, 2011; Stieb and others, 2012; Jedrychowski and others, 2013; Savitz and others, 2014; Chiu and others, 2014). The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) has identified both the estimation of windows of vulnerability and the identification of susceptible subpopulations as critical research directions in environmental health research (NIEHS, 2012). A critical methodological gap is the lack of available statistical methods to simultaneously identify windows of vulnerability and susceptible populations.

Windows of vulnerability are time periods during which exposure to a toxin has an increased association with current or future health status (Barr and others, 2000; West, 2002). Prenatal systems development is a multi-event process progressing sequentially from early gestation (Kajekar, 2007). The identification of windows of vulnerability, which in turn corresponds to sensitive stages of development, can inform our understanding of the underlying pathways through which an environmental exposure operates. Presumably, the window is defined by developmental specific events (i.e. gene expression changes, growth/cell density, vascularization etc.) that are transient and environmental exposure that is concurrent to these events.

The distributed lag model (DLM) framework has a long history in air pollution research and was originally developed for time-series analysis where an outcome observed on a given day is jointly regressed on exposures over a previous time period (Schwartz, 2000; Zanobetti and others, 2000). Several recent studies have applied DLMs to estimate windows vulnerability during which air pollution has an elevated association with preterm birth (Warren and others, 2012; Chang and others, 2015), decreased birth weight (Warren and others, 2013), childhood asthma (Hsu and others, 2015), and disrupted neurodevelopment (Chiu and others, 2016).

A critical consideration in the estimation of windows of vulnerability is that the prenatal developmental process is not homogeneous across all subgroups of individuals. For example, females display earlier fetal breathing than males (Becklake and Kauffmann, 1999). Because developmental timing varies, it is natural to hypothesize that the association between prenatal exposure and health outcomes in a given subgroup may not only vary in the effect size but in the timing of the window of vulnerability. Therefore, when interest focuses on windows of vulnerability, there are at least four potential patterns of effect heterogeneity: (i) both the effect size and the timing of the window vary by subgroup; (ii) only the effect size varies by subgroup; (iii) only the timing of the window varies by subgroup; or (iv) both the window and the effect size are the same for all subgroup. Existing methods only accommodate patterns (1) and (4), but not (2) and (3).

A DLM can estimate a common window and effect size (pattern 4) or, when stratified by group, estimate lagged effects assuming that both the effect size and the exposure window vary by subgroup (pattern 1), (e.g. Hsu and others, 2015; Chiu and others, 2016). The stratified DLM approach does not share information across groups relating to either the timing of the window or the effect size within the window. In the context of functional regression, Wei and others (2014) proposed a functional interaction model for gene-environment interactions with a time-varying environmental exposure. This approach shares information across groups (genotype) by assuming the same windows for each genotype but the effect is scaled by the number of major alleles (0, 1, or 2). Hence, this approach can estimate effects satisfying pattern 2 under the additional constraint that the effects are proportional to the number of major alleles. However, none of these approaches allow for the estimation across all four patterns of effect heterogeneity.

In this article, we propose a new method that provides greater flexibility in characterizing effect heterogeneity when identifying windows of vulnerability is of interest. The proposed Bayesian distributed lag interaction model (BDLIM) partitions the distributed lag function from a standard DLM into a time component that identifies windows of vulnerability and a scale component that quantifies the magnitude of the effect within the window. The approach allows both the window and the scale components to either vary or stay constant across subgroups. As such, the BDLIM framework can estimate a model with any of the four effect heterogeneity patterns. To our knowledge, models that assume the window of vulnerability is the same across subgroups but the effect within the window varies across groups, and vice versa, have not previously been considered in the literature. The proposed approach allows the user to directly answer the question of whether effect heterogeneity manifests itself via changes in the window of vulnerability, the magnitude of the effect, or both, which in turn more directly answers the question of whether an environmental exposure affects the developmental process of an infant similarly across subgroups.

In the BDLIM framework, the time-varying weight function is treated as a functional predictor that is scaled by the scalar effect size. This partitioning requires that identifiability constraints be placed on the parameters of the weight function. Under certain assumptions about effect heterogeneity the model can be reparameterized to relax the identifiability constraints on the parameter space and reduces to a mixed effects model. In other cases, including the general linear model setting for discrete responses, we use a slice sampler to efficiently estimate the model from the constrained space. We make software available for BDLIM in the R package regimes (REGression In Multivariate Exposure Settings).

We use BDLIM to estimate the association between fine particulate matter (PM ) measured weekly over pregnancy and two outcomes—birth weight for gestational age (BWGA)

) measured weekly over pregnancy and two outcomes—birth weight for gestational age (BWGA)  -score and asthma incidence–in a prospective Boston-area pregnancy cohort. Following Lakshmanan and others (2015), we evaluate whether the association between PM

-score and asthma incidence–in a prospective Boston-area pregnancy cohort. Following Lakshmanan and others (2015), we evaluate whether the association between PM and BWGA

and BWGA  -score varies by both sex and maternal obesity status. Following Hsu and others (2015), we evaluate how effects on asthma incidence vary by sex.

-score varies by both sex and maternal obesity status. Following Hsu and others (2015), we evaluate how effects on asthma incidence vary by sex.

2. The ACCESS data

We analyze data from the Asthma Coalition on Community, Environment, and Social Stress (ACCESS) project (Wright and others, 2008). ACCESS is a prospective, longitudinal study designed to investigate the effects of stress and other environmental factors, including air pollution, on asthma risk in an urban US setting. The ACCESS cohort includes data on 997 mother–child pairs that were recruited between August 2002 and January 2007. The women were at least 18 years of age, spoke English or Spanish, and received prenatal care at one of two Boston, MA area hospitals or affiliated community health centers. To date, the ACCESS cohort has been used to study the relationship of air pollution exposures, maternal stress, and other risk factors with outcomes including asthma, wheeze, and birth weight (Chiu and others, 2012; Hsu and others, 2015; Lakshmanan and others, 2015). Like previous ACCESS studies, we limit the analysis to full-term ( 37 weeks), live births with complete exposure, outcome, and covariate data.

37 weeks), live births with complete exposure, outcome, and covariate data.

For each child we consider BWGA  -scores and maternal-reported and clinician-diagnosed asthma as outcomes. The data contain maternal and child covariate information including: maternal age at enrollment; race/ethnicity (black, hispanic, and white); maternal education (two categories less than high school and high school diploma or more); self-reported smoking during pregnancy; indicator of maternal pre-pregnancy obesity; infant sex; maternal atopy (ever self-reported doctor-diagnosed asthma, eczema, or hay fever); season of birth; a previously described maternal stress index (Chiu and others, 2012); and a previously described neighborhood disadvantage index (Chiu and others, 2012). Maternal exposures of PM

-scores and maternal-reported and clinician-diagnosed asthma as outcomes. The data contain maternal and child covariate information including: maternal age at enrollment; race/ethnicity (black, hispanic, and white); maternal education (two categories less than high school and high school diploma or more); self-reported smoking during pregnancy; indicator of maternal pre-pregnancy obesity; infant sex; maternal atopy (ever self-reported doctor-diagnosed asthma, eczema, or hay fever); season of birth; a previously described maternal stress index (Chiu and others, 2012); and a previously described neighborhood disadvantage index (Chiu and others, 2012). Maternal exposures of PM were estimated with a hybrid land use regression model that incorporates satellite-derived aerosol optical depth measures (Kloog and others, 2011). Each mother was assigned an average PM

were estimated with a hybrid land use regression model that incorporates satellite-derived aerosol optical depth measures (Kloog and others, 2011). Each mother was assigned an average PM exposure value for each week of pregnancy based on the predicted value at her address of residence. We limit our analysis to exposure during the first 37 weeks of pregnancy.

exposure value for each week of pregnancy based on the predicted value at her address of residence. We limit our analysis to exposure during the first 37 weeks of pregnancy.

3. Bayesian distributed lag interaction models

3.1. Approach

Interest focuses on estimation of the association between time-varying exposure  ,

,  , and scalar outcome

, and scalar outcome  while controlling for a vector of baseline covariates

while controlling for a vector of baseline covariates  . We denote individuals by

. We denote individuals by  .

.

We parameterize the time-varying effect of exposure as  , where

, where  is a continuous weight function that captures temporal variation in the association between

is a continuous weight function that captures temporal variation in the association between  and

and  and

and  is the scalar effect size. The weight function

is the scalar effect size. The weight function  identifies windows of vulnerability in which the exposure effect is elevated relative to other time periods. To allow for heterogeneity among subgroups (e.g. infant sex) indexed by

identifies windows of vulnerability in which the exposure effect is elevated relative to other time periods. To allow for heterogeneity among subgroups (e.g. infant sex) indexed by  , we allow either or both of these quantities to vary across levels of

, we allow either or both of these quantities to vary across levels of  , denoted

, denoted  and

and  . Similar to a stratified DLM, this parameterization allows for group-level modification of both the window and effect size. In addition, this parameterization accommodates scenarios not yet considered whereby only the location of the window or only the magnitude of the effect, but not both, vary by group.

. Similar to a stratified DLM, this parameterization allows for group-level modification of both the window and effect size. In addition, this parameterization accommodates scenarios not yet considered whereby only the location of the window or only the magnitude of the effect, but not both, vary by group.

3.2. BDLIM for a single population

In the BDLIM, regression model for a single population with no effect heterogeneity we assume  and

and

| (3.1) |

where  is a monotone link function,

is a monotone link function,  is the intercept, and

is the intercept, and  is a vector of unknown regression coefficients for the covariates

is a vector of unknown regression coefficients for the covariates  . The model in (3.1) is similar to a functional linear model in which the total effect of exposure

. The model in (3.1) is similar to a functional linear model in which the total effect of exposure  on outcome

on outcome  at time

at time  is

is  . We will refer to this model as BDLIM-n, where the “n” indicates no heterogeneity between subgroups.

. We will refer to this model as BDLIM-n, where the “n” indicates no heterogeneity between subgroups.

For identifiability, we constrain the weight function such that  and

and  . The weight function is allowed to be both positive and negative to account for exposures that are a toxicant during some time periods but a nutrient during others. The constraint

. The weight function is allowed to be both positive and negative to account for exposures that are a toxicant during some time periods but a nutrient during others. The constraint  assures that

assures that  reflects the direction of the cumulative effect,

reflects the direction of the cumulative effect,  . The constraint

. The constraint  ensures that the magnitude of

ensures that the magnitude of  (i.e.

(i.e.  ) is identifiable.

) is identifiable.

To gain some insight into the BDLIM approach consider the case where  . In this case,

. In this case,  and (3.1) becomes a linear model with scalar exposure covariate equal to the mean exposure over the full pregnancy. However, once the weight function

and (3.1) becomes a linear model with scalar exposure covariate equal to the mean exposure over the full pregnancy. However, once the weight function  varies with

varies with  , the weighted exposure

, the weighted exposure  gives greater relative weight to some time windows. These up-weighted times are considered the windows of vulnerability.

gives greater relative weight to some time windows. These up-weighted times are considered the windows of vulnerability.

3.3. BDLIM model for effect heterogeneity

A key advantage of the BDLIM framework is the ability to estimate the three hypothesized patterns of heterogeneity where either  ,

,  , or both

, or both  and

and  vary by group. When either

vary by group. When either  or

or  is constant across groups, BDLIM yields a more parsimonious model that results in more powerful tests of an interaction.

is constant across groups, BDLIM yields a more parsimonious model that results in more powerful tests of an interaction.

Consider analysis of data for groups  . When both the effect size and the window of vulnerability are group-specific, the BDLIM model is

. When both the effect size and the window of vulnerability are group-specific, the BDLIM model is

| (3.2) |

where the subscript  denotes group

denotes group  to which individual

to which individual  belongs. We refer to this model as BDLIM-bw where “bw” indicates that both

belongs. We refer to this model as BDLIM-bw where “bw” indicates that both  and

and  vary across groups.

vary across groups.

The BDLIM framework extends to the new scenarios where only  or

or  varies by group. If it is hypothesized that groups share a common window, e.g. first trimester, but the groups are differentially susceptible within that window, the model is

varies by group. If it is hypothesized that groups share a common window, e.g. first trimester, but the groups are differentially susceptible within that window, the model is

| (3.3) |

which we denote BDLIM-b. Alternatively, if the effect is the same across groups but the windows are different, perhaps shifted by a few weeks, then the model, denoted BDLIM-w, is

| (3.4) |

Both BDLIM-b and BDLIM-w estimate patterns of effect heterogeneity not previously addressed.

3.4. Parameterization of the functional components

We assume a truncated basis function representation of both  and

and  . Common choices for the basis expansions include splines, wavelets, Fourier series, and principal components (PCs). We use the first

. Common choices for the basis expansions include splines, wavelets, Fourier series, and principal components (PCs). We use the first  PCs of the covariance matrix of

PCs of the covariance matrix of  as the basis to represent both

as the basis to represent both  and

and  for all groups. Here,

for all groups. Here,  is chosen to be the number of PCs that explain a prespecified proportion of the total variability in the exposures, for example 99% of the total variation. Hence,

is chosen to be the number of PCs that explain a prespecified proportion of the total variability in the exposures, for example 99% of the total variation. Hence,  and

and  .

.

In practice, we observe the exposures measured over a discrete grid, in our case  weeks of pregnancy. Let

weeks of pregnancy. Let  be a

be a  matrix with row

matrix with row  being the observed exposures for individual

being the observed exposures for individual  measured at times

measured at times  ,

,  . We use the covariance matrix of

. We use the covariance matrix of  to estimate the basis functions

to estimate the basis functions  . It is reasonable to expect that

. It is reasonable to expect that  is moderately smooth. However, the raw PCs of the covariance matrix of

is moderately smooth. However, the raw PCs of the covariance matrix of  are potentially rough. To obtain a smooth orthonormal basis, we use fast covariance estimation (FACE) proposed by Xiao and others (2016) to obtain the eigenfunctions of a smoothed covariance matrix, as implemented in the R package refund (Crainiceanu and others, 2014). There are several potential alternative approaches. In Appendix C of the supplementary materials available at Biostatistics online, we consider pre-smoothing the exposures and using the PCs of the covariance of the smoothed data. Morris (2015) discussed several methods for regularizing functional predictors that are sampled sparsely or on irregular grids.

are potentially rough. To obtain a smooth orthonormal basis, we use fast covariance estimation (FACE) proposed by Xiao and others (2016) to obtain the eigenfunctions of a smoothed covariance matrix, as implemented in the R package refund (Crainiceanu and others, 2014). There are several potential alternative approaches. In Appendix C of the supplementary materials available at Biostatistics online, we consider pre-smoothing the exposures and using the PCs of the covariance of the smoothed data. Morris (2015) discussed several methods for regularizing functional predictors that are sampled sparsely or on irregular grids.

The orthonormal PC basis facilitates implementation of the constraints on  . When

. When  , the constraint

, the constraint  is satisfied if and only if

is satisfied if and only if  , where

, where  . Additionally,

. Additionally,  holds for a set of observed times if and only if

holds for a set of observed times if and only if  , where

, where  is a

is a  -vector of ones and

-vector of ones and  is a

is a  matrix with row

matrix with row  taking the values

taking the values  . The resulting constrained parameter space on

. The resulting constrained parameter space on  is, therefore, defined by the surface of a unit

is, therefore, defined by the surface of a unit  -hemiball on one side of the hyperplane defined by

-hemiball on one side of the hyperplane defined by  . In some cases, this constraint can be alleviated as discussed in Section 3.5.

. In some cases, this constraint can be alleviated as discussed in Section 3.5.

Using the PC representation for both  and

and  the model in (3.1) is

the model in (3.1) is

| (3.5) |

where  and

and  . Because

. Because  is orthonormal,

is orthonormal,  . The model in (3.5) is easily adapted for effect heterogeneity with group specific

. The model in (3.5) is easily adapted for effect heterogeneity with group specific  and

and  .

.

3.5. Reparameterization to remove constraints in the linear model

For the normal linear model, BDLIM-n and BDLIM-bw can be reparameterized to reduce the computational burden imposed by the constrained parameter space. For BDLIM-n, the unknown parameters  for the weight functions

for the weight functions  are constrained to

are constrained to  and

and  ; however,

; however,  is unconstrained and

is unconstrained and  is also unconstrained in

is also unconstrained in  . Importantly,

. Importantly,  ,

,  , and

, and  are each uniquely identified from

are each uniquely identified from  . This generalizes to the BDLIM-bw with group specific

. This generalizes to the BDLIM-bw with group specific  . Hence, we reparameterize BDLIM-n and BDLIM-bw in terms of

. Hence, we reparameterize BDLIM-n and BDLIM-bw in terms of  and estimate the model with standard Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods without any constraints on the parameters. Then the posterior sample of

and estimate the model with standard Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods without any constraints on the parameters. Then the posterior sample of  can be deconvoluted into the posterior distributions of

can be deconvoluted into the posterior distributions of  and

and  by partitioning each MCMC draw. This approach is not applicable for the BDLIM-b and BDLIM-w (see Appendix A of the supplementary materials available at Biostatistics online) and we sample directly from the constrained parameter space as described in Section 3.6.

by partitioning each MCMC draw. This approach is not applicable for the BDLIM-b and BDLIM-w (see Appendix A of the supplementary materials available at Biostatistics online) and we sample directly from the constrained parameter space as described in Section 3.6.

3.6. Prior specification and computation

We complete the model by assigning prior distributions to the unknown regression parameters. The prior for  is uniform over the surface of the unit

is uniform over the surface of the unit  -hemiball for

-hemiball for  . The prior likelihood can be represented as proportional to a constrained mutlivariate standard normal,

. The prior likelihood can be represented as proportional to a constrained mutlivariate standard normal,  , where

, where  is an indicator function.

is an indicator function.

We assign normal priors to  and

and  . When reparameterized,

. When reparameterized,  becomes a scale parameter for

becomes a scale parameter for  . Specifically, we assume that

. Specifically, we assume that  and let

and let  . Then

. Then  , where

, where  is fixed and

is fixed and  . The resulting model has closed form full conditionals:

. The resulting model has closed form full conditionals:  can be sampled from a multivariate normal and

can be sampled from a multivariate normal and  from a generalized inverse-Gaussian distribution with density function

from a generalized inverse-Gaussian distribution with density function  , where

, where  ,

,  , and

, and  . Finally, we assume a flat prior on the intercept

. Finally, we assume a flat prior on the intercept  and, for the linear model with residuals

and, for the linear model with residuals  , a gamma prior on the precision parameter

, a gamma prior on the precision parameter  .

.

We use MCMC to simulate the posterior of the unknown parameters. For the BDLIM-n and BDLIM-bw in the linear model, all unknown parameters have simple conjugate forms and can be sampled via Gibbs sampler. For BDLIM-b, BDLIM-w, and models with a non-linear link function, we propose a slice sampling approach (Neal, 2003) based on the elliptical slice sampler proposed by Murray and others (2010) (see Appendix B of the supplementary materials available at Biostatistics online for details).

3.7. Summarizing the posterior of

Summarizing the posterior distribution of  deserves special consideration in light of the constraint

deserves special consideration in light of the constraint  . It is typical to summarize the posterior distribution with the posterior mean. However, the posterior mean of

. It is typical to summarize the posterior distribution with the posterior mean. However, the posterior mean of  almost surely does not satisfy

almost surely does not satisfy  and

and  . To obtain a point estimate for

. To obtain a point estimate for  such that

such that  and

and  , we take the posterior mean of

, we take the posterior mean of  in the topology of a

in the topology of a  -hemiball parameter space. We do this by taking the Bayes estimate with respect to the loss function

-hemiball parameter space. We do this by taking the Bayes estimate with respect to the loss function  . The resulting estimate

. The resulting estimate  is the posterior mean projected onto the

is the posterior mean projected onto the  -hemiball. That is,

-hemiball. That is,  , where

, where  is the posterior mean. Since each draw from the posterior satisfies

is the posterior mean. Since each draw from the posterior satisfies  , it follows that

, it follows that  . We identify windows of vulnerability as time periods where the pointwise 95% posterior intervals of

. We identify windows of vulnerability as time periods where the pointwise 95% posterior intervals of  do not contain 0.

do not contain 0.

A drawback to this point estimate is that in the absence of an effect ( ) or when

) or when  is not well identified by the data, the posterior of

is not well identified by the data, the posterior of  will reflect the prior. In this case, the projected estimator can be erratic; however, the posterior interval will still reflect the uncertainty in

will reflect the prior. In this case, the projected estimator can be erratic; however, the posterior interval will still reflect the uncertainty in  .

.

The effect  is interpretable even when a window is not identified. Because

is interpretable even when a window is not identified. Because  , the effect

, the effect  and the cumulative effect

and the cumulative effect  share the same significance level, i.e.

share the same significance level, i.e.  . Hence, the

. Hence, the  -level posterior interval for the cumulative effect will not contain 0 if and only if the

-level posterior interval for the cumulative effect will not contain 0 if and only if the  -level posterior interval for

-level posterior interval for  does not contain 0 and, regardless of whether a window is identified, we can conclude that there is an overall effect.

does not contain 0 and, regardless of whether a window is identified, we can conclude that there is an overall effect.

3.8. Comparing models and identifying the pattern of heterogeneity

We quantify the evidence in the data supporting each of the four potential patterns of effect heterogeneity with the mean log posterior predictive density (MLPPD). Specifically, for model  (where

(where  indicates the four BDLIM variants)

indicates the four BDLIM variants)  , where

, where  is the vector of all parameters for model

is the vector of all parameters for model  and

and  enumerates the draws from the simulated posterior distribution. We compute

enumerates the draws from the simulated posterior distribution. We compute  for each of the four effect heterogeneity models, then normalize as

for each of the four effect heterogeneity models, then normalize as

| (3.6) |

In the simulation study presented in Section 4.3, we compare the performance of computed using the normalized MLPPD to identify the correct model to that of the deviance information criterion (DIC, Spiegelhalter and others, 2002). Note that DIC is  , where

, where  is an additional penalty for model size. We show that normalized MLPPD is less likely to identify a misspecified pattern of effect heterogeneity.

is an additional penalty for model size. We show that normalized MLPPD is less likely to identify a misspecified pattern of effect heterogeneity.

4. Simulation

4.1. Simulation overview

We tested the performance of BDLIM with two simulation studies. Simulation A compares the BDLIM-n to a DLM when interest focuses on estimation of the effect of a time-varying exposure in a single group. Results suggest that the two methods perform similarly. We have relegated most of the details for this simulation to Appendix C of the supplementary materials available at Biostatistics online. We also compared tuning choices for BDLIM, including using different numbers of PCs and using natural splines to pre-smooth the exposures instead of smoothing the covariance matrix of  with FACE, in Appendix C of the supplementary materials available at Biostatistics online. Simulation B highlights the advantage of BDLIM for subgroup analyses and effect heterogeneity estimation.

with FACE, in Appendix C of the supplementary materials available at Biostatistics online. Simulation B highlights the advantage of BDLIM for subgroup analyses and effect heterogeneity estimation.

For both simulations, we used the observed exposures and covariates from the birth weight analysis of the ACCESS data. Using observed weekly air pollution levels during pregnancies ensures that the exposure data have realistic temporal trends and autocorrelations. Hence, the data contain  individuals with exposures measured at 37 evenly spaced time points, 10 binary covariates, 3 continuous covariates, and an intercept. For the second simulation, we divided the data into two groups, 239 girls (

individuals with exposures measured at 37 evenly spaced time points, 10 binary covariates, 3 continuous covariates, and an intercept. For the second simulation, we divided the data into two groups, 239 girls ( ) and 267 boys (

) and 267 boys ( ).

).

For each scenario, we simulated 1000 datasets and analyzed them with BDLIM and DLM. For BDLIM, we used 15 knots to estimate the covariance matrix. We used N priors on

priors on  and

and  and used the first

and used the first  PCs that explain 99% of the variation in exposure. We assumed Gaussian errors and put a gamma

PCs that explain 99% of the variation in exposure. We assumed Gaussian errors and put a gamma  prior on

prior on  . For DLM we used natural cubic splines with flat priors on the regression coefficients. We fit the DLM with degrees of freedom ranging from 3 to 10 and have presented results only from the best performing model.

. For DLM we used natural cubic splines with flat priors on the regression coefficients. We fit the DLM with degrees of freedom ranging from 3 to 10 and have presented results only from the best performing model.

4.2. Simulation A: Comparison to DLM with no effect heterogeneity

This simulation compares BDLIM-n with DLM when there is no effect heterogeneity. Both models are correctly specified but use different parameterizations and basis functions.

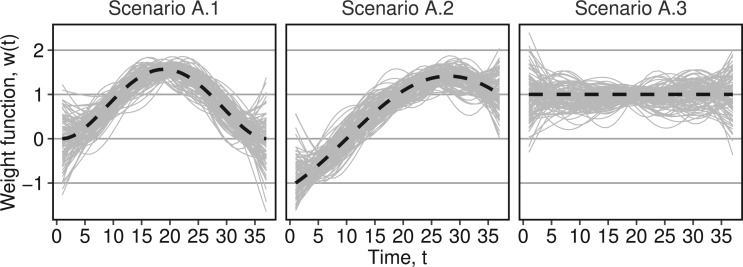

We used three scenarios each with data simulated from a different weight function:

| (4.1) |

| (4.2) |

| (4.3) |

where  is a beta function and

is a beta function and  is scaled to the unit interval. The superscripts identify the weight functions and correspond to the three scenarios in simulation A. The intercept and regression coefficients for the covariates are simulated as standard normals and we generated independent normal residuals with zero mean and standard deviation of six. Figure 1 shows the weight functions and the first 100 estimated weight functions using BDLIM-n.

is scaled to the unit interval. The superscripts identify the weight functions and correspond to the three scenarios in simulation A. The intercept and regression coefficients for the covariates are simulated as standard normals and we generated independent normal residuals with zero mean and standard deviation of six. Figure 1 shows the weight functions and the first 100 estimated weight functions using BDLIM-n.

Fig. 1.

Estimated weight functions  for simulation A. The grey lines show the estimated weight functions from BDLIM-n for the first 100 datasets. The thick black dashed line is the true weight functions.

for simulation A. The grey lines show the estimated weight functions from BDLIM-n for the first 100 datasets. The thick black dashed line is the true weight functions.

Both BDLIM-n and DLM can estimate the total time-varying effect  , while only BDLIM-n individually identifies

, while only BDLIM-n individually identifies  and

and  . For this reason, we focused the comparison on estimation of

. For this reason, we focused the comparison on estimation of  and the cumulative effect

and the cumulative effect  . Table 1 supplementary materials available at Biostatistics online shows that the models performed similarly. The models had similar model fit as measured by DIC, had similar RMSE and coverage near 95% for the estimate of

. Table 1 supplementary materials available at Biostatistics online shows that the models performed similarly. The models had similar model fit as measured by DIC, had similar RMSE and coverage near 95% for the estimate of  . For the cumulative effect,

. For the cumulative effect,  , we found that the bias and RMSE were similar for the methods and that both had posterior interval coverage near 95%. Hence, when there is no subgroup-specific analysis there is no information lost by using BDLIM instead of DLM.

, we found that the bias and RMSE were similar for the methods and that both had posterior interval coverage near 95%. Hence, when there is no subgroup-specific analysis there is no information lost by using BDLIM instead of DLM.

4.3. Simulation B: Performance with effect heterogeneity

The second simulation scenario compares BDLIM using the four parameterizations for exposure effect heterogeneity. The five simulation scenarios are as follows:

(1) B.1:

,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , no heterogeneity.

, no heterogeneity.(2) B.2 :

,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , heterogeneity in

, heterogeneity in  only.

only.(3) B.3:

,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , one group with no effect.

, one group with no effect.(4) B.4:

,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , heterogeneity in

, heterogeneity in  and

and  .

.(5) B.5:

,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , heterogeneity in

, heterogeneity in  only.

only.

For each simulation scenario, Table 1 shows the model fits from each model using normalized MLPPD, as described in Section 3.8, and DIC. For each of the five scenarios, there is more than one correctly specified model because BDLIM-bw is correctly specified under any of the four forms of effect heterogeneity. Use of MLPPD to identify the best fitting model (indicated with a  in Table 1) selects one of the correctly specified models with very high probability (at least 95% for all scenarios) and almost never selects a misspecified model. In contrast, DIC selects the simplest, correctly specified model (shown in bold in Table 1) at a higher rate but also identifies a misspecified model at a higher rate for Scenarios B.4 and B.5. Therefore, we conclude that use of MLPPD is a more conservative choice in that it selects a misspecified model at a lower rate at the cost of less power to rule out the most general BDLIM-bw model.

in Table 1) selects one of the correctly specified models with very high probability (at least 95% for all scenarios) and almost never selects a misspecified model. In contrast, DIC selects the simplest, correctly specified model (shown in bold in Table 1) at a higher rate but also identifies a misspecified model at a higher rate for Scenarios B.4 and B.5. Therefore, we conclude that use of MLPPD is a more conservative choice in that it selects a misspecified model at a lower rate at the cost of less power to rule out the most general BDLIM-bw model.

Table 1.

Comparison of model fit with four BDLIM parameterizations for simulation B

| Scenario | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B.1 | B.2 | B.3 | B.4 | B.5 | |

| Mean log posterior predictive distribution | |||||

| BDLIM-b | 0.30

|

0.61

|

0.64

|

0.02 | 0.06 |

| BDLIM-bw | 0.21

|

0.39

|

0.32

|

0.97

|

0.42

|

| BDLIM-n |

0.24

|

0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| BDLIM-w | 0.24

|

0.00 | 0.04 | 0.00 |

0.50

|

| Proportion model selected using mean log posterior predictive distribution | |||||

| BDLIM-b | 0.26

|

0.63

|

0.68

|

0.02 | 0.05 |

| BDLIM-bw | 0.13

|

0.37

|

0.28

|

0.98

|

0.28

|

| BDLIM-n |

0.30

|

0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| BDLIM-w | 0.31

|

0.00 | 0.04 | 0.00 |

0.65

|

| Mean DIC | |||||

| BDLIM-b | 3270.32

|

3270.85

|

3269.77

|

3287.60 | 3279.42 |

| BDLIM-bw | 3274.57

|

3275.51

|

3273.16

|

3276.02

|

3274.93

|

| BDLIM-n | 3270.44 |

3504.49 | 3302.76 | 3300.47 | 3281.10 |

| BDLIM-w | 3273.94

|

3360.48 | 3283.67 | 3293.79 |

3274.31

|

| Proportion model selected using DIC | |||||

| BDLIM-b | 0.31

|

0.92

|

0.85

|

0.11 | 0.15 |

| BDLIM-bw | 0.02

|

0.08

|

0.14

|

0.89

|

0.12

|

| BDLIM-n |

0.56

|

0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.10 |

| BDLIM-w | 0.11

|

0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 |

0.63

|

The top panel shows the mean MLPPD across the 1000 simulated datasets. The second panel shows the proportion of times each parameterization ranked as the best fitting model based on MLPPD. The third panel shows the average DIC for each parameterization. The fourth panel shows the proportion of times each model was selected as the best fitting model based on DIC. Numbers in bold indicate that the model is the simplest model that is correctly specified while an asterisk ( ) indicates that the model is correctly specified. Note that multiple models can be correctly specified and the BDLIM-bw is always correctly specified.

) indicates that the model is correctly specified. Note that multiple models can be correctly specified and the BDLIM-bw is always correctly specified.

Table 2 summarizes inference for  and

and  for the different BDLIM models. Overall, using the model that matches the pattern of heterogeneity (indicated by bold in Table 2) in the data provides the best inference. This is most notable for Scenario B.4 where both

for the different BDLIM models. Overall, using the model that matches the pattern of heterogeneity (indicated by bold in Table 2) in the data provides the best inference. This is most notable for Scenario B.4 where both  and

and  vary by group and BDLIM-bw provides accurate inference while the other approaches have greater bias, larger RMSE, and lower coverage for both

vary by group and BDLIM-bw provides accurate inference while the other approaches have greater bias, larger RMSE, and lower coverage for both  and

and  . Similarly, for Scenarios B.2 and B.3, BDLIM-b results in improved estimation of

. Similarly, for Scenarios B.2 and B.3, BDLIM-b results in improved estimation of  by sharing information across groups. To a lesser extent, BDLIM-w yields

by sharing information across groups. To a lesser extent, BDLIM-w yields  estimates with lower RMSE in Scenario B.5.

estimates with lower RMSE in Scenario B.5.

Table 2.

Simulation results for the inference on  and

and  using BDLIM for simulation B

using BDLIM for simulation B

Inference for

|

Inference for

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Bias | RMSE | Cover | RMSE | Cover | |

| Scenario B.1: No heterogeneity | ||||||

| BDLIM-b | Female | 0.000 | 0.011 | 0.973 | 0.248 | 0.954 |

| BDLIM-b | Male | -0.001 | 0.012 | 0.970 | 0.248 | 0.954 |

| BDLIM-bw | Female | 0.000 | 0.011 | 0.976 | 0.321 | 0.958 |

| BDLIM-bw | Male | -0.001 | 0.012 | 0.980 | 0.317 | 0.959 |

| BDLIM-n | Female | 0.005 | 0.011 | 0.947 | 0.258 | 0.947 |

| BDLIM-n | Male | 0.005 | 0.011 | 0.947 | 0.258 | 0.947 |

| BDLIM-w | Female | -0.001 | 0.010 | 0.970 | 0.317 | 0.957 |

| BDLIM-w | Male | -0.001 | 0.010 | 0.970 | 0.316 | 0.958 |

Scenario B.2: Heterogeneity in  only only | ||||||

| BDLIM-b | Female | 0.000 | 0.012 | 0.975 | 0.166 | 0.947 |

| BDLIM-b | Male | 0.001 | 0.017 | 0.954 | 0.166 | 0.947 |

| BDLIM-bw | Female | 0.008 | 0.013 | 0.964 | 0.335 | 0.944 |

| BDLIM-bw | Male | 0.007 | 0.013 | 0.934 | 0.173 | 0.956 |

| BDLIM-n | Female | -0.176 | 0.176 | 0.000 | 0.424 | 0.964 |

| BDLIM-n | Male | 0.124 | 0.125 | 0.000 | 0.424 | 0.964 |

| BDLIM-w | Female | -0.285 | 0.285 | 0.000 | 1.465 | 0.167 |

| BDLIM-w | Male | 0.015 | 0.018 | 0.806 | 0.163 | 0.966 |

| Scenario B.3: One group (males) with no effect | ||||||

| BDLIM-b | Female | 0.002 | 0.012 | 0.968 | 0.318 | 0.950 |

| BDLIM-b | Male | -0.002 | 0.012 | 0.957 | 0.318 | 0.950 |

| BDLIM-bw | Female | -0.010 | 0.014 | 0.926 | 0.280 | 0.960 |

| BDLIM-bw | Male | -0.006 | 0.020 | 0.970 | 0.650 | 0.983 |

| BDLIM-n | Female | -0.041 | 0.042 | 0.037 | 0.512 | 0.927 |

| BDLIM-n | Male | 0.059 | 0.059 | 0.015 | 0.512 | 0.927 |

| BDLIM-w | Female | -0.022 | 0.024 | 0.538 | 0.283 | 0.980 |

| BDLIM-w | Male | 0.078 | 0.079 | 0.000 | 1.307 | 0.527 |

Scenario B.4: Heterogeneity in both  and and

| ||||||

| BDLIM-b | Female | 0.006 | 0.018 | 0.941 | 0.648 | 0.151 |

| BDLIM-b | Male | -0.022 | 0.042 | 0.793 | 0.307 | 0.794 |

| BDLIM-bw | Female | 0.003 | 0.012 | 0.970 | 0.352 | 0.943 |

| BDLIM-bw | Male | -0.010 | 0.021 | 0.919 | 0.172 | 0.943 |

| BDLIM-n | Female | 0.048 | 0.049 | 0.031 | 0.559 | 0.236 |

| BDLIM-n | Male | -0.052 | 0.054 | 0.037 | 0.318 | 0.658 |

| BDLIM-w | Female | 0.043 | 0.045 | 0.039 | 0.561 | 0.756 |

| BDLIM-w | Male | -0.057 | 0.058 | 0.008 | 0.281 | 0.849 |

Scenario B.5: Heterogeneity in  only only | ||||||

| BDLIM-b | Female | 0.003 | 0.013 | 0.974 | 0.399 | 0.795 |

| BDLIM-b | Male | -0.022 | 0.028 | 0.674 | 0.580 | 0.537 |

| BDLIM-bw | Female | 0.000 | 0.011 | 0.976 | 0.315 | 0.960 |

| BDLIM-bw | Male | -0.007 | 0.018 | 0.944 | 0.355 | 0.949 |

| BDLIM-n | Female | -0.002 | 0.011 | 0.968 | 0.472 | 0.667 |

| BDLIM-n | Male | -0.002 | 0.011 | 0.968 | 0.490 | 0.655 |

| BDLIM-w | Female | -0.003 | 0.011 | 0.970 | 0.312 | 0.962 |

| BDLIM-w | Male | -0.003 | 0.011 | 0.970 | 0.328 | 0.950 |

For each scenario 1000 datasets were fit. The table shows the bias, RMSE, and 95% credible interval coverage for  and the RMSE and 95% credible interval coverage for

and the RMSE and 95% credible interval coverage for  . The bold rows indicate the model that was most frequently selected as the MLPPD model for that simulation scenario.

. The bold rows indicate the model that was most frequently selected as the MLPPD model for that simulation scenario.

In summary, BDLIM-n is nearly identical to a standard DLM when there is no heterogeneity across groups. When there is heterogeneity across groups, using BLDIM we can identify a correctly specified model with high probability. When that model is a reduced model, BDLIM results in improved inference of the weight function and effect size.

5. Analysis of prenatal air pollution exposure

5.1. Impact of sex and maternal obesity on air pollution effects on birth weight

We used BDLIM to estimate the association between PM and BWGA

and BWGA  -score. Following the analysis of Lakshmanan and others (2015), we estimated this association by child sex and maternal obesity status. Of the 506 children with complete data including BWGA

-score. Following the analysis of Lakshmanan and others (2015), we estimated this association by child sex and maternal obesity status. Of the 506 children with complete data including BWGA  -score, there were 155 females with non-obese mothers, 182 males with non-obese mothers, 84 females with obese mothers, and 85 males with obese mothers. Lakshmanan and others (2015) associated average PM

-score, there were 155 females with non-obese mothers, 182 males with non-obese mothers, 84 females with obese mothers, and 85 males with obese mothers. Lakshmanan and others (2015) associated average PM over the entire pregnancy with BWGA

over the entire pregnancy with BWGA  -score. Here, we estimate the association using the four variations of BDLIM to identify windows of vulnerability and use MLPPD to select the best fitting model. We assumed a normal linear model and used the same priors as described for the simulation in Section 4.1 and set

-score. Here, we estimate the association using the four variations of BDLIM to identify windows of vulnerability and use MLPPD to select the best fitting model. We assumed a normal linear model and used the same priors as described for the simulation in Section 4.1 and set  to explain 99% of the variance in

to explain 99% of the variance in  .

.

The BDLIM-b model had the highest normalized MLPPD at 0.96. The other models were 0.02 for BDLIM-bw, 0.01 for BDLIM-w, and 0.01 for BDLIM-n. Hence, we present results from the BDLIM-b, which assumes a single weight functions  shared by all four groups but group specific

shared by all four groups but group specific  .

.

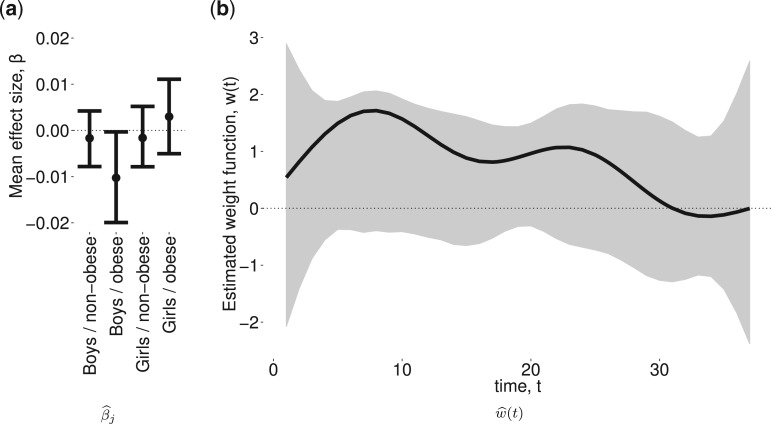

Figure 2a shows the estimated group-specific effects  . The results are consistent with those reported by Lakshmanan and others (2015), with a negative association between PM

. The results are consistent with those reported by Lakshmanan and others (2015), with a negative association between PM and BWGA

and BWGA  -score among boys with obese mothers but not in the other groups. In addition, the posterior probability of a pairwise difference between boys with obese mothers and the other three groups range from 0.93 to 0.97. The posterior difference for the pairwise comparisons between the three non-significant groups range from 0.50 to 0.84 suggesting little evidence of differences between those groups. Further, because the model is saturated we can perform an ANOVA decomposition on the posterior sample to investigate main effects of sex and obesity as well as an interaction effect (see Appendix D of the supplementary materials available at Biostatistics online for details).

-score among boys with obese mothers but not in the other groups. In addition, the posterior probability of a pairwise difference between boys with obese mothers and the other three groups range from 0.93 to 0.97. The posterior difference for the pairwise comparisons between the three non-significant groups range from 0.50 to 0.84 suggesting little evidence of differences between those groups. Further, because the model is saturated we can perform an ANOVA decomposition on the posterior sample to investigate main effects of sex and obesity as well as an interaction effect (see Appendix D of the supplementary materials available at Biostatistics online for details).

Fig. 2.

Estimated group specific effect sizes  (left panel) and weight function

(left panel) and weight function  (right panel) using the BDLIM-b model for the BWGA

(right panel) using the BDLIM-b model for the BWGA  -score analysis.

-score analysis.

The estimated weight function  (Figure 2b) shows a trend of increased vulnerability in the earlier part of pregnancy, approximately weeks 5–20. Although we do not identify a window with high probability, the estimated cumulative effect over the full pregnancy always has the same sign and significance level as

(Figure 2b) shows a trend of increased vulnerability in the earlier part of pregnancy, approximately weeks 5–20. Although we do not identify a window with high probability, the estimated cumulative effect over the full pregnancy always has the same sign and significance level as  . For male infants with obese mothers we estimate a cumulative effect of -0.225 with 95% credible interval (-0.476, -0.001). Hence, the results are suggestive of a negative association between PM

. For male infants with obese mothers we estimate a cumulative effect of -0.225 with 95% credible interval (-0.476, -0.001). Hence, the results are suggestive of a negative association between PM exposures in early pregnancy and lower BWGA

exposures in early pregnancy and lower BWGA  -score among boys with obese mothers.

-score among boys with obese mothers.

The estimated time-varying effects  are presented in Appendix D of the supplementary materials available at Biostatistics online. Results from the BDLIM-bw model are presented there as well. Comparing the results using BDLIM-bw and BDLIM-b shows that the model with a shared weight function BDLIM-b is more suggestive of the location of the window of vulnerability and has, on average, 14% smaller posterior standard deviation for

are presented in Appendix D of the supplementary materials available at Biostatistics online. Results from the BDLIM-bw model are presented there as well. Comparing the results using BDLIM-bw and BDLIM-b shows that the model with a shared weight function BDLIM-b is more suggestive of the location of the window of vulnerability and has, on average, 14% smaller posterior standard deviation for  . Therefore, there is evidence that the magnitude of the effect varies across groups, but no evidence that the timing of the window varies across groups primarily because there is no effect in three of the four groups.

. Therefore, there is evidence that the magnitude of the effect varies across groups, but no evidence that the timing of the window varies across groups primarily because there is no effect in three of the four groups.

5.2. Sex-specific effects of prenatal air pollution on asthma incidence

We next used a logistic BDLIM to estimate sex-specific associations between PM and childhood asthma incidence in the ACCESS cohort. Hsu and others (2015) analyzed these data by stratifying by sex and applying a standard DLM to data in each stratum. Here we assess whether the magnitude of the effect, the timing of the effect, or both vary by sex. This analysis included data from 544 births with complete data including asthma. Again, BDLIM-b was the best fitting model for the asthma analysis with normalized MLPPD of 0.43. The others were 0.21 for BDLIM-bw, 0.20 for BDLIM-n, and 0.17 for BDLIM-w. We describe the results from the BDLIM-b model.

and childhood asthma incidence in the ACCESS cohort. Hsu and others (2015) analyzed these data by stratifying by sex and applying a standard DLM to data in each stratum. Here we assess whether the magnitude of the effect, the timing of the effect, or both vary by sex. This analysis included data from 544 births with complete data including asthma. Again, BDLIM-b was the best fitting model for the asthma analysis with normalized MLPPD of 0.43. The others were 0.21 for BDLIM-bw, 0.20 for BDLIM-n, and 0.17 for BDLIM-w. We describe the results from the BDLIM-b model.

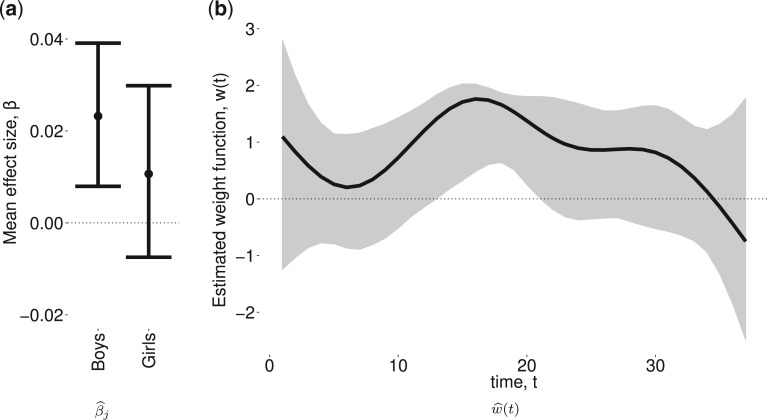

Figure 3 shows the estimated weight function  and the estimated group-specific effects

and the estimated group-specific effects  using BDLIM-b. Figure 3a shows a positive and statistically significant association between PM

using BDLIM-b. Figure 3a shows a positive and statistically significant association between PM exposure and asthma incidence in boys but not in girls. The weight function (Figure 3b) identifies a window of vulnerability in 13–21. Hence, PM

exposure and asthma incidence in boys but not in girls. The weight function (Figure 3b) identifies a window of vulnerability in 13–21. Hence, PM exposures during the 13–21 were positively associated with asthma among boys. This is comparable to the widows identified by Hsu and others (2015) which were 12–26 for boys using a sex-stratified analysis and 14–20 when testing sex differences. Figure 6 of the supplementary materials available at Biostatistics online shows the estimated sex-specific odds ratios for a 10

exposures during the 13–21 were positively associated with asthma among boys. This is comparable to the widows identified by Hsu and others (2015) which were 12–26 for boys using a sex-stratified analysis and 14–20 when testing sex differences. Figure 6 of the supplementary materials available at Biostatistics online shows the estimated sex-specific odds ratios for a 10 /m

/m increase in PM

increase in PM , which peak around 1.25 for boys. The results using BDLIM-bw were very similar and are included in Appendix E of the supplementary materials available at Biostatistics online; however, BDLIM-b yielded posterior standard deviations of

, which peak around 1.25 for boys. The results using BDLIM-bw were very similar and are included in Appendix E of the supplementary materials available at Biostatistics online; however, BDLIM-b yielded posterior standard deviations of  that were 10% smaller than their BDLIM-bw counterparts.

that were 10% smaller than their BDLIM-bw counterparts.

Fig. 3.

Estimated group specific effect sizes  (left panel) and weight function

(left panel) and weight function  (right panel) using the BDLIM-b model on the asthma analysis.

(right panel) using the BDLIM-b model on the asthma analysis.

6. Discussion

In this paper we have proposed BDLIM as a new tool that can be used estimate effect heterogeneity in time-varying exposures. This addresses a critical methodological gap for simultaneous estimation of windows of vulnerability and identifying susceptible subpopulations. Specifically, BDLIM allows for estimation of effect heterogeneity when subgroups have a common window of vulnerability but different effects within the window (BDLIM-b) or when subgroups have the same effect size but in different windows (BDLIM-w). In these scenarios, the resulting estimates had reduced bias and RMSE, an advantage of pooling information across groups when the effects are not different. We demonstrated this advantage both in the simulation study and the data analysis.

The proposed approach partitions the time-varying effect into two components. The first is a constrained functional predictor that captures the temporal variation in the effect and identifies windows of vulnerability. The second component is a scalar effect size that quantifies the effect within the window. In some situations the constraint on the parameters of the weight function can be removed by reparameterizing the model. In this case the scalar effect size becomes a scale parameter in the model with a generalized inverse-Gaussian full conditional, which allows for simulating the posterior with a Gibbs sampler. In other situations, including generalized linear models, we use a slice sampler to efficiently simulate the posterior of the contained parameters. The constraints of the weight function make summarizing the posterior of the weight function difficult because the posterior mean does not satisfy the constraints. We address this by using a point estimate that is the Bayes estimate with respect to a non-standard loss function specifically chosen to yield a posterior summary that satisfies the constraints. We then identify windows of vulnerability where the pointwise posterior interval does not contain zero.

We analyzed data from the ACCESS cohort on the association between prenatal exposure to PM and both birth weight and asthma incidence. In both cases the BDLIM analyses suggested a common window of vulnerability but different effect sizes within the window for both outcomes. Hence, in both analyses the model providing the best fit to the data could not have been estimated using existing methods. Our results identified a window of 13–21 where PM

and both birth weight and asthma incidence. In both cases the BDLIM analyses suggested a common window of vulnerability but different effect sizes within the window for both outcomes. Hence, in both analyses the model providing the best fit to the data could not have been estimated using existing methods. Our results identified a window of 13–21 where PM exposures were associated with increased asthma incidence in boys but not in girls. In the analysis of the birth weight data, there was strong evidence of a negative association between PM

exposures were associated with increased asthma incidence in boys but not in girls. In the analysis of the birth weight data, there was strong evidence of a negative association between PM in the earlier part of pregnancy and decreased BWGA

in the earlier part of pregnancy and decreased BWGA  -score among boys born to obese mothers.

-score among boys born to obese mothers.

The proposed approach assumes that  and/or

and/or  are the same for all groups or different for all groups. When there are more than two groups it may be of interest to understand if only certain pairs of groups share one or more component. In the BWGA

are the same for all groups or different for all groups. When there are more than two groups it may be of interest to understand if only certain pairs of groups share one or more component. In the BWGA  -score analysis we performed an a posteriori ANOVA decomposition to investigate if the main effect of child sex or maternal obesity status is important. This could be done because the model for

-score analysis we performed an a posteriori ANOVA decomposition to investigate if the main effect of child sex or maternal obesity status is important. This could be done because the model for  was saturated. Another simple approach would be to define groups based on preliminary analysis and rerun the model. In the BWGA

was saturated. Another simple approach would be to define groups based on preliminary analysis and rerun the model. In the BWGA  -score analysis, this would mean two groups: boys with obese mothers in one group and everyone else in another. A more sophisticated extension would be to extend the approach to directly model how covariates influence each component, such as modeling the weight functions as

-score analysis, this would mean two groups: boys with obese mothers in one group and everyone else in another. A more sophisticated extension would be to extend the approach to directly model how covariates influence each component, such as modeling the weight functions as  .

.

Identifying susceptible populations and windows of vulnerability are critical areas of future research as highlighted in the NIEHS strategic plan (NIEHS, 2012). BDLIM provides an essential tool for simultaneous identification of susceptible populations and critical windows of vulnerability when estimating of the health effects of environmental exposures.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Supplementary Material

supplementary materials is available at http://biostatistics.oxfordjournals.org. Software for BDLIM is included in the R package regimes available at anderwilson.github.io/regimes/.

Funding

The ACCESS study has been supported by grants (R01 ES010932, R01 ES013744; U01 HL072494, and R01 HL080674 to W.R.J., PI). This work was supported by USEPA grant 834798 and NIH grants (ES020871, ES007142, CA134294, ES000002, P30 ES023515). This publication’s contents are solely the responsibility of the grantee and do not necessarily represent the official views of the US EPA.

References

- Barr M., DeSesso J. M., Lau C. S., Osmond C., Ozanne S. E., Sadler T. W., Simmons R. A. and Sonawane B. R. (2000). Workshop to identify critical windows of exposure for children’s health: cardiovascular and endocrine work group summary. Environmental Health Perspectives 108(Suppl 3), 569–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becklake M. R. and Kauffmann F. (1999). Gender differences in airway behaviour over the human life span. Thorax 54, 1119–1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H. H., Warren J. L., Darrow L. A., Reich B. J. and Waller L. A. (2015). Assessment of critical exposure and outcome windows in time-to-event analysis with application to air pollution and preterm birth study. Biostatistics 16, 509–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu Y.-H. M., Coull B. A., Cohen S., Wooley A. and Wright R. J. (2012). Prenatal and postnatal maternal stress and wheeze in urban children: effect of maternal sensitization. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 186, 147–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu Y.-H. M. Coull B. A., Sternthal M. J., Kloog I., Schwartz J., Cohen S. and Wright R. J. (2014). Effects of prenatal community violence and ambient air pollution on childhood wheeze in an urban population. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 133, 713–722.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu Y.-H. M., Hsu H.-H. L., Coull B. A., Bellinger D. C., Kloog I., Schwartz J., Wright R. O. and Wright R. J. (2016). Prenatal particulate air pollution and neurodevelopment in urban children: examining sensitive windows and sex-specific associations. Environment International 87, 56–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crainiceanu C., Reiss P., Goldsmith J. and Huang L. (2014). refund: Regression with Functional Data. R package version 0.1-11. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu H.-H. L., Chiu Y.-H. M., Coull B. A, Kloog I., Schwartz J., Lee A., Wright R. O. and Wright R. J. (2015). Prenatal particulate air Pollution and asthma onset in urban children. Identifying sensitive windows and sex differences. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 192, 1052–1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jedrychowski W. A., Perera F. P., Spengler J. D., Mroz E., Stigter L., Flak E., Majewska R., Klimaszewska-Rembiasz M. and Jacek R. (2013). Intrauterine exposure to fine particulate matter as a risk factor for increased susceptibility to acute broncho-pulmonary infections in early childhood. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health 216, 395–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajekar R. (2007). Environmental factors and developmental outcomes in the lung. Pharmacology and Therapeutics 114, 129–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly F. J. and Fussell J. C. (2011). Air pollution and airway disease. Clinical and Experimental Allergy 41, 1059–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloog I., Koutrakis P., Coull B. A., Lee H. J. and Schwartz J. (2011). Assessing temporally and spatially resolved PM 2.5 exposures for epidemiological studies using satellite aerosol optical depth measurements. Atmospheric Environment 45, 6267–6275. [Google Scholar]

- Lakshmanan A., Chiu Y.-H. M., Coull B. A., Just A. C., Maxwell S. L., Schwartz J., Gryparis A., Kloog I., Wright R. J. and Wright R. O. (2015). Associations between prenatal traffic-related air pollution exposure and birth weight: modification by sex and maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index. Environmental research 137, 268–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris J. S. (2015). Functional regression. Annual Review of Statistics and Its Application 2, 321–359. [Google Scholar]

- Murray I., Adams R. P. and MacKay D. J. C. (2010). Elliptical slice sampling. Journal of Machine Learning Research: W&CP 9, 541–548. [Google Scholar]

- Neal R. M. (2003). Slice sampling. The Annals of Statistics 31, 705–767. [Google Scholar]

- NIEHS. (2012). NIEHS Strategic Plan. Technical Report, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

- Savitz D. A., Bobb J. F., Carr J. L., Clougherty J. E., Dominici F., Elston B., Ito K., Ross Z., Yee M. and Matte T. D. (2014). Ambient fine particulate matter, nitrogen dioxide, and term birth weight in New York, New York. American Journal of Epidemiology 179, 457–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz J. (2000). The distributed lag between air pollution and daily deaths. Epidemiology 11, 320–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah P. S. and Balkhair T. (2011). Air pollution and birth outcomes: a systematic review. Environment International 37, 498–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegelhalter D. J., Best N. G., Carlin B. P. and Van Der Linde A. (2002). Bayesian measures of model complexity and fit. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B 64, 583–616. [Google Scholar]

- Šrám R. J., Binková B., Dejmek J. and Bobak M. (2005). Ambient air pollution and pregnancy outcomes: a review of the literature. Environmental Health Perspectives 113, 375–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stieb D. M., Chen L, Eshoul M. and Judek S. (2012). Ambient air pollution, birth weight and preterm birth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environmental Research 117, 100–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren Joshua, Fuentes Montserrat, Herring Amy H and Langlois Peter H. (2012). Spatial-temporal modeling of the association between air pollution exposure and preterm birth: identifying critical windows of exposure. Biometrics 68, 1157–1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren J. L, Fuentes M., Herring A. H. and Langlois P. H. (2013). Air pollution metric analysis while determining susceptible periods of pregnancy for low birth weight. ISRN Obstetrics and Gynecology 2013, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei P., Tang H. and Li D. (2014). Functional logistic regression approach to detecting gene by longitudinal environmental exposure interaction in a case-control study. Genetic Epidemiology 38, 638–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West L. J. (2002). Defining critical windows in the development of the human immune system. Human & Experimental Toxicology 21, 499–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright R. J., Suglia S. F., Levy J., Fortun K., Shields A., Subramanian S. V. and Wright R. (2008). Transdisciplinary research strategies for understanding socially patterned disease: the Asthma Coalition on Community, Environment, and Social Stress (ACCESS) project as a case study. Ciencia & Saude Coletiva 13, 1729–1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao L., Zipunnikov V., Ruppert D. and Crainiceanu C. (2016). Fast covariance estimation for high-dimensional functional data. Statistics and Computing 26, 409–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanobetti A., Wand M. P., Schwartz J. and Ryan L. M. (2000). Generalized additive distributed lag models: quantifying mortality displacement. Biostatistics 1, 279–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.