The future of biodiversity conservation depends on efforts applied across large landscapes, the scale at which many key ecological and evolutionary processes take place. Because the seeds of the National Park system were sown in the United States over 130 years ago, conservation practitioners have increasingly demonstrated that critical conservation goals—including responsiveness to climate change and representation of species, ecosystems, and habitats—can be achieved only if protected areas are functionally connected and embedded within larger, permeable landscapes (Trombulak and Baldwin 2010).

The scope of such efforts in terms of the number of species, ecosystems, geophysical features, landowners, and jurisdictions is so large that landscape-scale conservation cannot succeed without coordinated planning (Aycrigg et al. 2016). It cannot succeed on a continental scale without coordination by the federal government. Jurisdictional boundaries and narrow site-specific foci must be transcended if conservation efforts are to fully protect biological diversity in the face of climate change, expanding urban areas, wildfires, and other ecological developments. Planning must occur at a regional scale because for protected-area systems, the whole is more than the sum of the parts.

Recognition of this led in 2010 to the creation of landscape conservation cooperatives (LCCs), an important step in the application of systematic conservation planning (Margules and Pressey 2000), to build robust conservation strategies with a large-scale regional framing that account for future climate change. They were created through an order by the then secretary of the interior Ken Salazar (Order no. 3289), which also invested in the US Geological Survey climate science centers (CSCs). The LCCs were meant to complement the CSCs and were formed under the Science Applications initiative of the US Fish and Wildlife Service.

Unfortunately, the current US presidential administration has “zeroed out” Science Applications in its budget request, and there are signals that the elimination of the system of LCCs is imminent. We argue that the LCC system is the most promising government-sponsored system of conservation planning based on ecoregional patterns in existence, has not yet had time to mature as a scientific organization, and deserves the opportunity to improve on its initial work to achieve its crucial mission.

Although The Nature Conservancy and other nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) have long practiced ecoregion-based planning (Groves et al. 2002, Dinerstein et al. 2017), the LCCs represent the first time any federal government has instituted a wildlife conservation program that promotes connectivity and persistence at the continental scale. A significant strength of the LCCs is their integration of decision-makers with the decision-support system of conservation science. Each LCC is governed by a voluntary steering committee, with members representing conservation and resource management partners from a variety of government agencies, tribal governments, NGOs, and others located within the LCC geographic region. Staffing is minimal and generally only includes a coordinator and science coordinator.

The field of systematic conservation planning has matured to the point at which it can be applied effectively at continental scales. Influenced by a variety of fields from computer science to conservation biology, it uses quantitative geospatial methods to spatially prioritize conservation decisions (Ball et al. 2009). The essential characteristic is representation of ecosystems, species, and processes in a reserve network that is connected and resilient to environmental change (Anderson et al. 2014). The LCC system is spatially extensive and lends itself well to applying science to achieve these outcomes: (a) placement of core conservation areas, (b) creation of network connectivity responsive to the changing climate, (c) assessment of vulnerability to land-use change, (d) integration of social constraints with biodiversity and ecosystem-service goals, and (e) comparison of alternative scenarios.

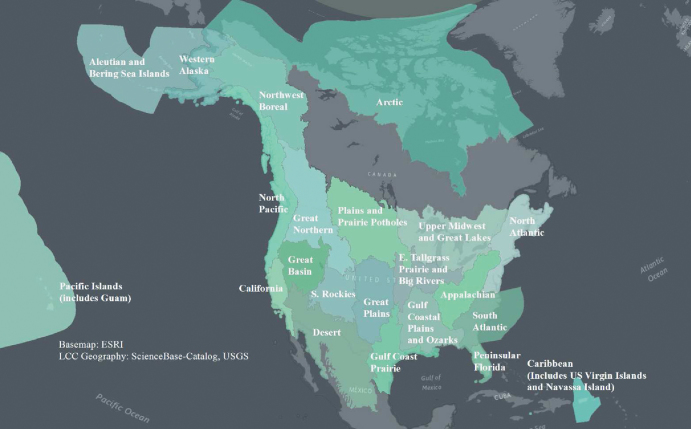

Although systematic conservation planning requires extensive data sets on conservation targets, the LCC structure facilitates acquisition of these data, saving money as cooperators share data and expertise. LCC science is conducted by conservation scientists in academic institutions, private companies, and NGOs. Because the science of systematic conservation planning is improved by stakeholder involvement, this collective “bottom-up” approach provides a source of expertise for modelers, crucial for establishing conservation targets, setting goals, and reviewing results. Finally, the LCC structure is perfectly aligned to disseminate results, because cooperators form a conduit back to their agencies, organizations, institutions, and the public. The 22 LCCs (figure 1) are further connected into a nationwide network serviced by a network coordinator and small staff.

Figure 1.

The geography of transboundary planning cooperatives established by the United States in 2010 to aid in wildlife adaptation to changing climate.

Success of the landscape conservation cooperatives

How does one measure the success of a scientific organization dedicated to landscape-scale conservation? Typical measures of science success, as in publications and grants, can be applied to conservation organizations, but how science is put into practice also needs to be recognized. Since their inception, the LCCs have organized themselves internally; sponsored hundreds of research and planning projects; engaged in public outreach; and disseminated reports, data, and new methodologies (NAS 2016). Over 40 peer-reviewed papers have been published, and more are in the publication pipeline. Actual on-the-ground applications resulting in real conservation progress are, so far, less obvious. But as a recent review of the LCC program by the National Academy of Sciences noted, “Given the youth of this program … it is too soon to expect ‘measureable improvements in the health of fish, wildlife, and their habitats’” (NAS 2016). We know that when applied in the real world, landscape-scale conservation planning works. For example, one of the first large landscape conservation initiatives, Yellowstone to Yukon, used systematic conservation planning to achieve numerous conservation goals (Y2Y 2014).

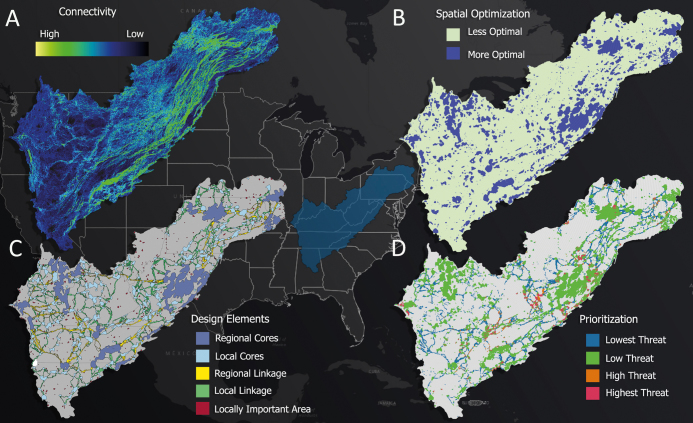

Multistate and NGO initiatives for wildlife conservation existed prior to the LCCs. However, these are challenging to maintain because no federally managed cooperative exists to fund and collate the spatially explicit data needed to help prioritize regional conservation spending. When LCCs focused on whole landscapes, species and ecosystems, ecological processes, human influences and benefits, and prioritization of actions in time and space, they produced plans that, if implemented, could provide for the conservation of the nation's biological diversity (cf. figure 2).

Figure 2.

A landscape conservation design project for the Appalachian LCC: (a) a supercomputer-enabled habitat connectivity model estimating the probability of gene flow for focal species; (b) near-optimization of terrestrial, aquatic, and ecosystem-service targets; (c) functional conservation design elements; and (d) prioritization based on measured threats (Leonard et al. 2017).

Landscape conservation cooperatives at risk

However, the future of the LCCs is uncertain. In May 2017, Department of the Interior (DOI) Secretary Zinke received a letter from the House Committee on Natural Resources that challenged the existence of the CSCs and LCCs, stating that these initiatives had little to show for the $149 million they had received. In fact, even before the 2019 budget goes to Congress, the DOI has targeted the Science Applications initiative that houses the LCCs for elimination. In May, LCC staff received a letter from the acting assistant director for science applications indicating that federal funding would end for the LCCs, with some hope that “through other programs, the Service will continue to work with external stakeholders to support conservation efforts, share information, and help natural communities thrive.” However, there is no indication that this would involve anything other than traditional site-specific projects that stand little chance of promoting ecological resilience.

If the goal of conservation in the face of climate change has merit, then the LCC program must continue. No other initiative has the scope or potential to bring together the diverse set of participants required to succeed. So far, it has accomplished its preliminary goal of creating a framework to allow multiple levels of governance to cooperate in addressing landscape-level challenges that cross jurisdictional boundaries. The potential for achieving more given additional time is great. And its $26 million annual price tag is a tiny fraction of the administration's $79 billion budget request for science (Science News Staff 2017).

Improving the landscape conservation cooperatives

Certainly, the work of the LCCs could improve, as it was hampered in its early years by organizational and methodological inefficiencies. Changes in three particular areas would help overcome the concerns raised by Secretary Zinke and the House Natural Resources Committee.

Focus the mission

Although the enabling mission of the LCCs was broadly directed toward coordinating an effective response to the impacts of climate change on land, water, fish, wildlife, and cultural resources (Salazar 2010), the mission of the LCCs now needs to focus specifically on landscape-scale conservation planning rather than on ad hoc projects. Myriad regionally focused “science needs” were initially proposed as projects when a landscape-level biodiversity mission had yet to emerge. In retrospect, LCCs that focused on landscape-scale planning (e.g., Pickens et al. 2017) have made the biggest impact. Those that funneled resources into supporting regional planning, such as developing measures of ecological integrity (e.g., Theobald 2013), also moved the science forward. Furthermore, the LCCs should articulate more clearly how they provide information that will help avoid land-use conflicts that arise from biodiversity conservation, energy, food, and timber.

Aim for consistency and applicability

Too much effort has been expended within each region developing new planning methodologies. Instead, methodologies should be chosen from among those already peer reviewed and tested and applied uniformly across all LCC regions to allow for their eventual integration. Funding for basic research that develops new analytics should be avoided; instead, research should be directed toward filling critical data gaps and supplement existing methodologies. LCCs should use optimal existing science and not default to the most expedient. And LCCs should take the opportunity to raise the bar for scientific literacy within the conservation community and invest effort in explaining the methods of systematic conservation planning to cooperators.

Promote scalability

Most land-use decisions are made locally. However, conservation plans are typically developed for larger areas and have the potential to guide resource allocation to priority localities and promote cooperation and sharing resources. Consequently, planning methods should readily scale across local and regional levels. A plan based on LCC efforts should be able to address relevant questions at each level of the spatial hierarchy.

Any new scientific endeavor can be improved after its start, especially if (a) it involves a goal as complex as conservation in the face of climate change and (b) human participation is crucial to its success. In its initial years, the LCC network was not focused on a clear, science-based mission, nor did it consistently implement consistent principles and methods. Regardless, LCCs have made significant progress toward their goal. Defunding them now squanders this opportunity to develop comprehensive conservation action plans that are responsive to climate change, wasting the investment already made and making it harder for a future administration sympathetic to climate-based conservation to restart such an effort.

Wildlife and flora underpin national identity and have enormous economic value. Planning to conserve these resources at multiple spatial scales should not be left solely to the states, NGOs, and the private sector. The challenge transcends state boundaries and must be taken up by the federal government. As Secretary Zinke has said, “We’ve got to start looking at our lands in terms of complete watersheds and ecosystems, rather than isolated assets. We need to think about wildlife corridors, because it turns out wildlife doesn’t just stay on federal lands” (Strassel 2017). LCCs provide the geographic framework, cooperative venue, and ability to fund, coordinate, and disseminate relevant science that is unmatched by any other system.

Acknowledgments

The authors have received funding for research from the landscape conservation cooperative system (RFB, PL, MA) or have served on its governing body (LS). PL is currently employed by the US Fish and Widllife Service. All of the authors participated in writing the manuscript and/or preparing the figures (PL).

References cited

- Anderson MG, Clark M, Olivero-Sheldon A. 2014. Estimating climate resilience for conservation across geophysical settings. Conservation Biology 28: 959–970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aycrigg JL, et al. 2016. Completing the system: Opportunities and challenges for a national habitat conservation system. BioScience 66: 774–784. [Google Scholar]

- Ball IR, Possingham HP, Watts M. 2009. Marxan and relatives: Software for spatial conservation prioritization. 185–195 in Moilanen A, Wilson KA, Possingham HP, eds. Spatial Conservation Prioritisation: Quantitative Methods and Computational Tools. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dinerstein E, et al. 2017. An ecoregion-based approach to protecting half the terrestrial realm. BioScience 67: 534–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves CR, Jensen DB, Valutis LL, Redford KH, Shaffer ML, Scott JM, Baumgartner JV, Higgins JV, Beck MW, Anderson MG. 2002. Planning for biodiversity conservation: Putting conservation science into practice. BioScience 52: 499–512. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard PB, Baldwin RF, Hanks D. 2017. Landscape-scale conservation design across biotic realms: Sequential integration of aquatic and terrestrial landscapes. Scientific Reports 7 (art. 14556). doi:10.1038/s41598-017-15304-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margules CR, Pressey RL. 2000. Systematic conservation planning. Nature 405: 243–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [NAS] National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2016. A Review of the Landscape Conservation Cooperatives. National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pickens BA, Mordecai RS, Ashton Drew C, Alexander-Vaughn LB, Keister AS, Morris HLC, Collazo JA. 2017. Indicator-driven conservation planning across terrestrial, freshwater aquatic, and marine ecosystems of the South Atlantic, USA. Journal of Fish and Wildlife Management 8: 219–233. [Google Scholar]

- Science News Staff 2017. What's in Trump's 2018 budget request for science? Science. (22 November 2017; www.sciencemag.org/news/2017/05/what-s-trump-s-2018-budget-request-science) [Google Scholar]

- Strassel KA. 2017. A return to the conservation ethic. Wall Street Journal. (22 November 2017; www.wsj.com/articles/a-return-to-the-conservation-ethic-1506723867) [Google Scholar]

- Theobald DM. 2013. A general model to quantify ecological integrity for landscape assessments and US application. Landscape Ecology 10: 1859–1874. [Google Scholar]

- Trombulak SC, Baldwin RF, eds. 2010. Landscape-Scale Conservation Planning. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- [Y2Y] Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative 2014. The Yellowstone to Yukon Vision, Progress and Possibility: Making Connections Naturally 20 Years. Y2Y. (22 November 2017; https://y2y.net/publications/y2y_vision_20_years_of_progress.pdf) [Google Scholar]