Abstract

Background:

Patients’ suffering has been increasingly investigated by health-care researchers especially in the chronically ill. Suffering is viewed as a progressive negative consequence that associated with pain, impaired self-esteem, and social alienation. This qualitative evidence synthesis aimed to provide further insights into the application of phenomenology in explaining suffering among patients with chronic illnesses.

Methods:

Studies included in this qualitative evidence synthesis study were retrieved by searching from the following electronic databases: CINAHL, PubMed Central, and EBSCO.

Findings:

Phenomenology is regarded as influential to generate in-depth evidence about suffering that are grounded in chronically ill patients’ perspectives. The philosophical constructs of suffering suggested fundamental dimensions such as stress, distress, hopelessness, and depression along with pain. Evidence encompasses the entire manifestation of suffering in which all interrelated meanings are understood and referred to a unique structure. Hermeneutic phenomenology was adopted as an effective strategy to elucidate human experience leading to the discovery of the embedded meanings of life experience.

Conclusion:

The phenomenological approach provides nursing research with the pathway to explore patients’ suffering experiences in the chronically ill.

Keywords: chronic, nursing, phenomenology, suffering

Introduction

Phenomenology was established as an alternative method to the traditional objectivist approach of modern science, in which scientific objectivity functions to explain independent human elements (1,2). Phenomenology relays on the latent observation that aims to understand phenomenon from the underlying features rather than explain it based on the visible/apparent manifestations (1). Edmund Husserl is considered the “father” of phenomenology (3). Phenomenology emerged at the end of the 19th century to challenge controversial issues in the philosophical science, which included an argument of how effective was positivism to answer the questions about human sciences (4). Husserl maintained that the nature of phenomena was as appeared through consciousness. He focused on the minds and objects that occur within human experience (4). Phenomenology deals with the world as lived by a person, not the world or reality as something separate from the person. Particularly, he stated that there is a phenomenon only when there is an individual who experiences the phenomenon. The phenomenological method aims to provide a full description of the lived experiences, or what that experience means to those who live it (4). It is viewed that subjective information is substantial in the assessment of human experience, and human performance is affected by what people perceive to be real life (3). According to Lopez and Willis, phenomenology focuses on the belief that this method will shed light on personal knowledge and perceptions to uncover the lived experiences of those being studied (3). Thus, the understanding of phenomenology is based on personal experience within a specific environment (5,6).

The Oxford English Dictionary defines suffering as to “undergo, experience, be subjected to pain, loss, grief, defeat, change, punishment, and wrong” (cited in (7)). Suffering is viewed as a natural consequence of human experience and reactions (8,9). It is perceived as a threat or loss of a person’s self, which is accompanied by a loss of control or pain (10). According to Eriksson, suffering is an ontological concept characterized by struggling between good and evil as a unique experience, not solely with pain, but also reflecting the sense of dying from something (10). Despite its harmful impact, suffering is acknowledged as an integral part of human life experience, which applies to the human beings using its characteristics rather than measuring or grading it (9,11). Indeed, individuals who experience resilience to questioning prefer to remain silent. Therefore, nurses are in a position to detect circumstances of suffering by careful listening and sharing with patients their own experiences (8,12). Suffering is a significant consequence of human experience that has accounted for a greater proportion of philosophers’ writings (13). It has also a prominent impact on the nursing profession as one of the core health-care profession that deals directly with patients, families, and their needs (12). Suffering can be defined as a unique lived experience which is particularly determined by individual meaning (14).

The goal of this article was to critically review the application of phenomenology in exploring patients’ suffering during their chronic illness.

Method

A search was conducted in the following electronic databases: CINAHL, PubMed Central, and EBESCO for the years between 1995 and 2015. This range of years was chosen for selecting related studies conveniently rather than approaching publications within a specific period of time. The key words used for searching were “Phenomenology” AND “Suffering” AND “Chronic illness.” Inclusion criteria are qualitative articles that studied suffering in chronically ill patients using a phenomenological approach. In addition, the included studies should have explored suffering as the center of investigation. Studies that used phenomenology to investigate suffering for a specific therapeutic regimen or treatment modalities were excluded from the review. Also, sufferings examined in acute illnesses or in any short-term therapies were also excluded. The included studies were appraised for their quality and validation using the Critical Appraisal Skill Program (CASP) which was published by CASP, UK (15). This tool was used to evaluate each selected study using a specific format designed for qualitative studies and consists of 10 questions. Using this appraisal tool, all included studies met the basic components of qualitative research, which included the validity of the study, the usefulness of the results, and the clinical importance of the results.

Findings

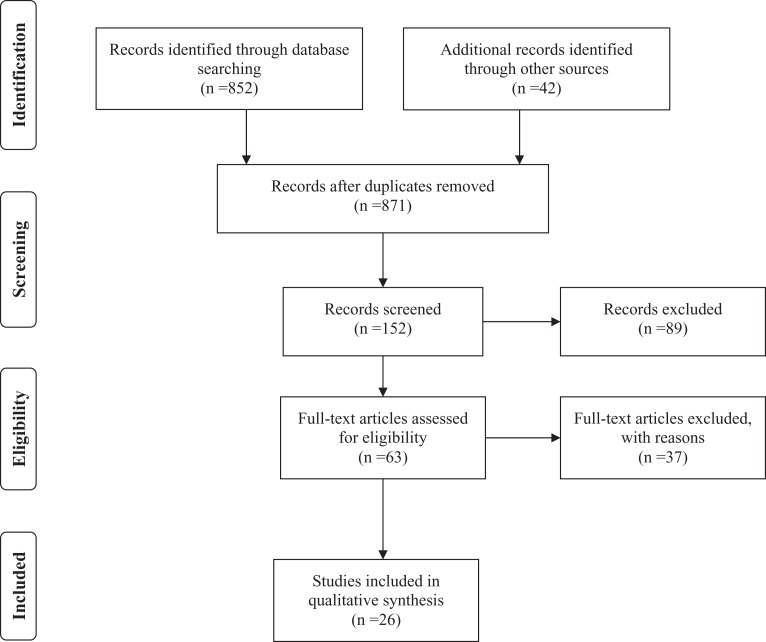

The systematic searching for the above databases retrieved an initial 894 papers. After screening the titles, 152 were selected and moved to the next step of abstract screening. Of these papers, 89 papers were excluded due to their irrelevancy to the study objectives, 14 papers were published in languages other than English, and 23 were duplicated articles between the above databases. As illustrated in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) flowchart (Figure 1), the total number of papers included in this review was 26. The following are 3 formulated themes of this qualitative review.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart of the included studies in the qualitative evidence synthesis.

Suffering and Its Consequences in the Context of Phenomenology

Suffering is defined according to specific attributes. According to Rodgers and Cowles (13), these attributes include individualized, subjective, and complex experiences that are associated with negative meanings. This definition leads to the status of perceived loss of an individual’s integrity, autonomy, and humanity (13). In addition to loss, suffering is characterized by other features such as loneliness, vulnerability, fear, and hopelessness (8). Although suffering cannot be easily assessed or measured, it holds a unique abstractness, visible physical signs such as crying or grimacing can be detected because these subjective markers can contribute to the overall complex nature of this complex concept (13). This complexity is also integrated with its physical, cognitive, affective, social, and spiritual components. In fact, the most prevailing attribute of suffering is the described meaning of a situation. This meaning is particularly negative in nature because it characterizes suffering as quite profound, a tremendous sense of loss of integrity, or control over these stressful situations (13). Although pain is not viewed as an essential part of the suffering experience, it was agreed that pain is frequently a common precursor of suffering (7,8).

Nordman et al reported that a patient’s suffering is described in 3 dimensions: suffering related to illness and its treatment, suffering related to life, and suffering related to care. Suffering related to sickness and treatment includes many features such as body or emotional pain, depression, and anxiety (10). Suffering related to life and existence refers to the tension between the need of hope and hopelessness life or death. Suffering related to care is associated with neglecting and exhausting power leading to the feel of violated dignity and human values (10,16). Because nurses are directly concerned with the last dimension, suffering from care might emerge from lack of care, neglecting patients dignity, violation of patients’ right, and ignoring psychosocial needs (10,17).

Most often, suffering is illustrated as a result of a preceded physical illness, disability, and disfigurement (7,12). Occasionally, certain social problems are respected as suffering’s influential factors such as problems of losing employment, homelessness, poverty, and disassociation from society (13). However, because these attributes are individualized in nature, persons may vary in their capacity to experience suffering. Such individual variations include consciousness, cognitive and emotional awareness, knowledge of past and future, sense of completeness as a complete human, sense of aims, or purposes in life. The deficiency or partial deficiency of these capacities could lead to an uncertain experience of suffering and a threat of negative described meaning as mentioned previously (7,13).

A study by Arman et al aimed to understand and interpret the meaning of patients’ experiences of suffering related to health care from ethical and ontological perspectives. Sixteen women with breast cancer in Sweden and Finland were interviewed. The result showed that suffering related to health care was a complex phenomenon and constituted an ethical challenge to health-care providers. Women’s experiences of suffering related to health care demonstrated intense experiences of suffering related to cancer care including the whole experience of life, health, and illness in physical, mental, and spiritual senses (17).

Pain is one of the confusing terms used to demonstrate the phenomenon of suffering. Instead, other terms such as stress, distress, depression, and anxiety are well established to convey the notion of suffering (4). Likewise, Seyama and Kanda introduced terms such as anxiety, grief, and conflict to express the idea of suffering as a major challenge for families with a patient having cancer. Obviously, these descriptions alter the values of reality because all of them entail negative consequences in nature. It is acknowledged that these negative consequences may produce withdrawal, dysfunctional, and a radically deteriorating quality of life for suffering people (7). It might also include feelings of hopelessness and confrontation. However, despite negative interpretations attached to the consequences of suffering, they may constitute positive reinforcement outcomes in personal growth, strength, values, and visions (2,7,13).

The individual’s ability to cope, act, and react with external and internal conditions of suffering is variable. It is neither being able to ignore or belittle the impact of suffering on physical and emotional pain nor being able to accept and tolerate all physical, emotional, cognitive, and spiritual consequences of suffering (13,16). The individual coping and reaction with these conditions related to suffering can also be purposeful leading to fighting and resisting the main sources of physical, emotional, and cognitive provoking factors of suffering (5,18).

For instance, Bentur et al explored the coping strategies for existential and spiritual suffering at the end of life of secular Jews with advanced-stage cancer. The phenomenological approach was employed. The findings of the study revealed that these patients with advanced-stage cancer utilized several methods to cope with existential and spiritual suffering. These coping strategies were openness and choosing to face reality; connectedness and the significance of family; pursuit of meaning; the connection of body, mind, and spirit with humor; and a positive outlook. This study demonstrated robust methodology in which a variety of patients’ characteristics and conditions were integrated in the study and strengthened the emerged evidence (2).

The Applicability of Phenomenology in Understanding Suffering

As far as the phenomenological approach is concerned, the phenomenon of suffering is part of human experience that is basically manifested based on individualized recognition of life (2,19). Theoretical understanding of suffering is necessary to gain knowledge about the required caring strategies in clinical practice. Raholm discussed the necessity to understand the patients’ world in an ontological prospective to present the unique sense of suffering in the proper way (14). Caregiver needs not only this theoretical understanding of the concept but also the effective way to deal with sensitive experiences while providing care for a suffering person (7,13). Phenomenology provides sufficient awareness of, and sensitivity to, the dimensions of rationalizing expressive and creative ideas through the concrete lived experiences, and intensification of inner meanings (12,19). Although the traditional quantitative approach gains higher popularity in the assessment of human experience and caring, the phenomenological approach becomes prominent in overcoming uncertainty when dealing with narrated lived experiences (8,19).

Hagren et al stated that phenomenology which becomes a broad method in nursing research is being used to assess suffering and its impact on quality of life, considering the subjective experience of the individual (16). Because, alleviating suffering associated with illness is one of the primary goals of nursing care, understanding these sensitive conditions can help to alleviate a patient’s suffering (16). Raholm argued that suffering can be understood through 3 hermeneutic steps. The first hermeneutic step includes understanding the fundamentals of suffering by allowing a person to speak while listening carefully. This understanding is subject to sharing a common language between the 2 parties (14). The way of thinking about the patient’s situation should take the form of a story-sharing process which consists of an expression of innocence and hearing of their desire to receive caring. The second hermeneutic step includes interpreting the fundamentals of suffering. In this phase, nurses are required to identify their personal beliefs that could explicitly influence the explanation of patients’ condition (14). Once both nurses’ and patients’ beliefs reach a point of understanding, nurses can undertake the third hermeneutic step that includes planning for patients to overcome their suffering (6,14). Generally, nurses can utilize phenomenology for discovering patients’ lived experiences in their world because the nursing profession is acknowledged as the caring rather than curing profession in which patients’ suffering is a major concern of caring (12).

The following studies examined the phenomenon of suffering using different phenomenological approaches. Chio et al explored suffering and its related lived experience related to changes in the healing processes among 21 terminally ill Taiwanese patients with cancer. The phenomenological–hermeneutic approach was used. The result showed that those terminally ill patients experienced spiritual suffering as a result of their perceptions of death which threatened the meanings and purpose of their existence. Further factors associated with spiritual suffering included physical pain, treatment complications, uncertain illness progression, disability problems, and lack of support. The emerged spiritual suffering was ascribed to emotional aspects (feelings of fear, sadness, and hopelessness) and aspects of thoughts (pessimistic feelings toward dying and negative thoughts about self). In addition, spiritual suffering was conceived as spiritual pain which demonstrated conflict and disharmony between the patients’ supportive systems and the reality of the current situation. The findings of this study provided an exhaustive description of the lived experience by those terminally ill patients (20).

Similarly, Seyama and Kanda in their study clarified the concept of suffering among families of patients with cancer. The study revealed that suffering of families with a cancer member was manifested in 2 constructs “unpleasant psychological pain” and “uncertainty about the future.” Suffering was attributed to the state of “hopeless situation” due to persistent feeling of depression that kept them indoors and missing a sense of emotion and joy and anger that withholds the essence of harmonious relations with others (7). Also, Pareek et al assessed suffering in patients with postpartum psychoses. The phenomenological approach was used to collect and analyze patients’ data which were obtained from individual interviewing of 100 women. The study found that the women experiencing postpartum psychosis exhibited mood symptoms affecting life and impaired functioning (21). Hagren et al examined 15 end-stage renal disease patient’s experiences of suffering. Patients in this study alleged that the main areas of suffering were the loss of freedom due to long-life dependency on a hemodialysis machine as a lifeline (16). The previous studies were disease-specific phenomenological research which associated with such uniqueness to specific groups of patients and therefore transferability to other chronic illnesses might be limited.

Berglund et al conducted a phenomenological study to examine the phenomenon of suffering experienced in relation to health-care needs among patients in hospital settings. The results showed that patients suffered during caregiving when they felt undervalued or mistreated. Suffering was found to increase due to neglecting a holistic and patient-centered care. It can be described as having the following 4 components: to be mistreated, to struggle for one’s health-care needs and autonomy, to feel powerless, and to feel fragmented and objectified (6).

Finally, Sigurdardottir et al studied the consequences of childhood sexual abuse on health and well-being Icelandic men. Phenomenology was used as the study methodology. The findings of the study indicated that the men described deep and almost unbearable suffering that affected their whole life. They had very difficult childhood, living with indisposition, bullying, learning difficulties, and behavioral problems. Some men anesthetized themselves with alcohol and illicit drugs. They have suffered psychologically and physically and have had relational and sexual intimacy problems (9). The methodological properties of this study did not provide specific inquiry related to physical and psychological consequences as one deals with manifest observation and the other deals with latent observation.

Based on these applications, suffering is an experience that affects the entire human functioning. Patients suffering may entail a set of consequences that are interrelated with the therapeutic interventions especially in the prolonged medical plans. In turn, caregivers play the pivotal role in assessing and eradicating the majority of treatment-related suffering, while the patients receive the conventional therapy.

Approaching Suffering Through Nursing Research

The role of the nursing profession in preventing and diminishing human suffering is more embedded in identifying the profound meaning of suffering in each individual situation. While nursing professionals have a rich experience of caring for those who are sick and dying, suffering is also of critical concern to nurses (22). Therefore, understanding the patients’ perspective is a valued goal of nursing practice and depends on the ability to listen, imagine, and interpret changes in the patients’ lives (23). Once the nurses understand the phenomenological approach, they will willingly implement this philosophy to explore changes in the patients’ lives because phenomenology facilitates understanding the reality of how one experiences the world in which he or she lives (12). Phenomenologists attempt to provide an exhaustive meaning to the internal suffering through discovering the person’s experience in the lived world along with a detailed description of that experience and strive to place it within the surrounding stressors (5,12).

Although nursing is an intersubjective and interpersonal, relationship-based activity, the phenomenological approach is particularly appropriate to the nursing research paradigm that allows exploring the best routes to promote well-being in suffering patients (16). The concept of suffering would not be examined thoroughly without robust philosophical underpinning supported by such methodological paradigms found in the psychosocial sciences. Once the nurse–patient relationship is fundamentally concerned with the subjective issues, it is acknowledged that the natural sciences will explicitly eliminate issues that cannot be objectively observed and publicly verified (12). Furthermore, Casell (as cited in (24)), who criticized the medical approach that tends to focus only on the body’s functions, found that splitting physical, psychological, and social aspects from suffering is not possible because of the holistic distress threat to the state of entire intactness.

Recently, nurses have increased their awareness of using phenomenology for building their evidence from patients’ experience (3). Although patients’ perspectives describe and explain the relationship between personal experience and disease, phenomenology offers nurses and clinicians an approach that helps to elucidate the meanings of interactions between an individual and his or her environment (1). Theoretically, phenomenological inquiry collects evidence from both the descriptive and explanatory approach (5). It is recognized in the literature that nurses use both descriptive phenomenology and interpretive hermeneutic phenomenology by which hermeneutic phenomenology goes beyond basic description of concepts to emphasize the embedded meanings of common life experience not only from the individual’s point of view but also from social and historical effects (25). The implication of that on the nursing profession appears when nurses understand the importance and practice the opportunity of understanding patients’ experiences in everyday situations, then they discuss and communicate their findings leading to significantly changed action plans for subsequent situations in the future (4,26). Former nursing researchers have alleged that phenomenology facilitated individuals with difficulties, stressors, and overwhelming situations to find order for their situations by means of developing a coherent live history and being able to interpret it (25 –27).

Conclusion

Suffering is one of the phenomena that nursing is concerned with based on its roots in individual’s lived experience. Because it is a complex human response affecting physical, psychological, social, and spiritual aspects, it may decrease self-integrity and induces loneliness, withdrawal, feelings of helplessness, and despair. The phenomenological approach is acknowledged as a route to insight into the understanding of human experiences. While phenomenology contributes to empirical, moral, and social understanding, its role in establishing a framework of living experience and revealing the nature of human experience cannot be undervalued. This qualitative synthesis unveiled the magnificence of understanding human experience through phenomenology. It is acknowledged that suffering would not be possible to be explored through the traditional objectivism approaches. In the light of chronic illnesses, phenomenology provides researchers with the path for eliciting patients’ lived experience along with maintaining credibility and comprehensiveness of people’s entire feelings.

Substantially, the main objective of phenomenological inquiry is not only to understand each individual’s various types of suffering in human diverse life contexts as such assessment occurred in the real clinical practice. In parallel, phenomenology, especially hermeneutic interpretive phenomenology, also tries to find the “essential meaning structures” of a certain human phenomenon (eg, suffering in long-term illness) that are experienced by group of people who share common characteristics (eg, patients with cancer, survivors of childhood abuse, etc). This means that the type of illness and its severity may influence the nature of suffering shared among patients.

It was acknowledged that nurses’ involvement in patients’ experience is very effective to understand aspects surrounding suffering and complaints. Nurses have to go beyond the conventional spectrum of practice and take into account other factors that influence suffering as a result of illness, life, or even care. By other words, assessing patients’ experience through a simple descriptive inquiry often yields unreliable indicators to patients’ embedded suffering. Thus, using such explanatory method such as phenomenology would help to embrace the complexity of patients’ living experience including physical, cognitive, affective, social, and spiritual components. The phenomenological approach is the key to gain an exhaustive meaning of patients’ experiences in the chronically ill. It is recommended that nursing research should integrate the philosophy of hermeneutic phenomenology to enhance better understanding of patients’ needs. In addition, the application of phenomenology is also directed toward understanding the essential meaning structure of suffering, as the main phenomenon, which is shared by a certain group of patients.

Author Biographies

Mahmoud Al Kalaldeh is a researcher working in the field of nursing. Since phenomenology is one of methodological approaches grounded in his research interest, integrating evidence from qualitative studies is also undertaken.

Ghada Abu Shosha is a researcher who mainly focuses on qualitative research in pediatric oncology patients. A number of published studies in this field were conducted in Jordan.

Najah Saiah is an assistant professor in nursing administration. She started to develop a unique experience in applying qualitative approach in her area of interest.

Omar Salameh is a master holder lecturer in nursing administration. It is noted that he joins many research teams in the school to enrich his knowledge qualitative research.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: All authors have made a substantial contribution to this manuscript and prepared the manuscript’s contents mutually.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Sadala M, Adorno R. Phenomenology as a method to investigate the experience lived: a perspective from Husserl and Merleau Ponty’s thought. J Adv Nurs. 2002;37:282–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bentur N, Stark D, Resnizky S, Symon Z. Coping strategies for existential and spiritual suffering in Israeli patients with advanced cancer. Isr J Health Policy Res. 2014;3:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lopez K, Willis D. Descriptive versus interpretive phenomenology: their contributions to nursing knowledge. Qual Health Res. 2004;14:726–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Laverty S. Hermeneutic phenomenology and phenomenology: a comparison of historical and methodological considerations. Int J Qual Methods. 2003;2:21–35. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zalm J, Bergum V. Hermeneutic-phenomenology: providing living knowledge for nursing practice. J Adv Nurs. 2000;31:211–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Berglund M, Westin L, Svanstrom R, Sundler A. Suffering caused by care-patients’ experiences from hospital settings. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2012;7:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Seyama R, Kanda K. Suffering among the families of cancer patients: conceptual analysis. Kitakanto Med J. 2008;85:71–6. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kazanowski M, Perrin K, Potter M, Sheehan C. The silence of suffering: breaking the sound barriers. J Holist Nurs. 2007;25:195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sigurdardottir S, Halldorsdottir S, Bender S. Deep and almost unbearable suffering: consequences of childhood sexual abuse for men’s health and well-being. Scand J Caring Sci. 2012;26:688–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nordman T, Santavirta N, Eriksson K. Developing an instrument to evaluate suffering related to care. Scand J Caring Sci. 2008;22:608–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lindholm L, Rehnsfeldt A, Arman M, Hamrin E. Significant others’ experience of suffering when living with women with breast cancer. Scand J Caring Sci. 2002;16:248–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rapport F, Wainwright P. Phenomenology as a paradigm of movement. Nurs Inq. 2006;13:228–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rodgers B, Cowles K. A conceptual foundation for human suffering in nursing care and research. J Adv Nurs. 1997;25:1048–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Raholm M. Uncovering the ethics of suffering using a narrative approach. Nursing Ethics. 2008;15:62–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. 2017. CASP Qualitative Research Checklist [online] Retrieved from http://casp-uk.net. Accessed June 10, 2016.

- 16. Hagren B, Pettersen I, Severinsson E, Lutzen K, Clyne N. The haemodialysis machine as a lifeline: experiences of suffering from end-stage renal disease. J Adv Nurs. 2001;34:196–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Arman M, Rehnsfeldt A, Lindholm L, Hamrin E, Eriksson K. Suffering related to health care: a study of breast cancer patients’ experiences. Int J Nurs Pract. 2004;10:248–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Diehl U. Human suffering as a challenge for the meaning of life. Existenze. 2009;4:36–44. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ohlen J. Evocation of meaning through poetic condensation of narratives in empirical phenomenological inquiry into human suffering. Qual Health Res. 2003;13:557–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chio C, Shin F, Chiou J, Lin HW, Hsiao FH, Chen YT. The Lived experiences of spiritual suffering and the healing process among Taiwanese patients with terminal cancer. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17:735–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pareek V, Kherada S, Gocher S, Sharma SK, Dhaka BL. A study of phenomenology in patients suffering from postpartum psychosis. Delhi Psychiatry J. 2014;17:270–5. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Maeve M. Weaving a fabric of moral meaning: how nurses live with suffering and death. J Adv Nurs. 1998;27:1136–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gjengedal E, Kvigne K, Kirkevold M. Gaining access to the life-world of women suffering from stroke: methodological issues in empirical phenomenological studies. J Adv Nurs. 2002;40:61–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Arman M, Rehnsfeldt A. The hidden suffering among breast cancer patients: a qualitative metasynthesis. Qual Health Res. 2003;13:510–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Borimnejad L, Yekta Z, Nasrabadi A. Lived experience of women suffering from vitiligo: a phenomenological study. Qual Rep. 2006;11:335–49. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Annels M. Triangulation of qualitative approaches: hermeneutical phenomenology and grounded theory. J Adv Nurs. 2006;56:55–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chesla C. Nursing science and chronic illness: Articulating suffering and possibility in family life. J Fam Life. 2005;11:371–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]