Abstract

Background

Recurrent miscarriage, also referred to as recurrent spontaneous abortion (RSA), affects 1 – 5% of couples and has a multifactorial genesis. Acquired and congenital thrombophilia have been discussed as hemostatic risk factors in the pathogenesis of RSA.

Method

This review article was based on a selective search of the literature in PubMed. There was a special focus on the current body of evidence studying the association between RSA and antiphospholipid syndrome and hereditary thrombophilia disorders.

Results

Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is an acquired autoimmune thrombophilia and recurrent miscarriage is one of its clinical classification criteria. The presence of lupus anticoagulant has been shown to be the most important serologic risk factor for developing complications of pregnancy. A combination of low-dose acetylsalicylic acid and heparin has shown significant benefits with regard to pregnancy outcomes and APS-related miscarriage. Some congenital thrombophilic disorders also have an increased associated risk of developing RSA, although the risk is lower than for APS. The current analysis does not sufficiently support the analogous administration of heparin as prophylaxis against miscarriage in women with congenital thrombophilia in the same way as it is used in antiphospholipid syndrome. The data on rare, combined or homozygous thrombophilias and their impact on RSA are still insufficient.

Conclusion

In contrast to antiphospholipid syndrome, the current data from studies on recurrent spontaneous abortion do not support the prophylactic administration of heparin to treat women with maternal hereditary thrombophilia in subsequent pregnancies. Nevertheless, the maternal risk of thromboembolic events must determine the indication for thrombosis prophylaxis in pregnancy.

Key words: loss of pregnancy, preeclampsia, pregnancy

Zusammenfassung

Hintergrund Wiederholte Fehlgeburten, auch wiederholte Spontanaborte (WSA) genannt, werden von 1 – 5% der Paare erlebt und weisen eine multifaktorielle Genese auf. Erworbene und angeborene Thrombophilien werden als hämostaseologische Risikofaktoren in der Pathogenese diskutiert.

Methode Die Übersichtsarbeit basiert auf einer selektiven Literaturrecherche in PubMed. Auf die aktuelle Evidenzlage zu WSA beim Antiphospholipidsyndrom und den hereditären Thrombophilien wird besonders hingewiesen.

Ergebnisse Das Antiphospholipidsyndrom (APS) ist eine erworbene, autoimmun-vermittelte Thrombophilie, bei der wiederholte Fehlgeburten zu den klinischen Klassifikationskriterien gehören. Von den serologischen Kriterien hat sich der Nachweis des Lupusantikoagulans als wichtigster Risikofaktor für die Entwicklung von Schwangerschaftskomplikationen herauskristallisiert. Der kombinierte Einsatz von niedrigdosiertem ASS mit Heparin zeigte einen deutlichen Vorteil hinsichtlich des Schwangerschaftsausgangs bei APS-bedingten Fehlgeburten. Bei einigen angeborenen Thrombophilien besteht auch eine erhöhte Risikoassoziation mit der Entstehung von WSA, wenn auch geringer als beim APS. Der Analogschluss zum Antiphospholipidsyndrom bezüglich des Einsatzes von Heparin zur Abortprophylaxe wird durch die aktuellen Analysen nicht hinreichend unterstützt. Daten zu seltenen, kombinierten bzw. homozygoten Thrombophilien bez. Fehlgeburten sind unzureichend.

Schlussfolgerung Anders als beim Antiphospholipidsyndrom stellen wiederholte Spontanaborte für sich bei mütterlicher hereditärer Thrombophilie nach aktueller Studienlage keine Indikation zur prophylaktischen Heparingabe in einer Folgeschwangerschaft dar. Unabhängig davon bestimmt das maternale Risiko für thromboembolische Ereignisse die Indikation für eine Thromboseprophylaxe in der Schwangerschaft.

Schlüsselwörter: Abort, Präeklampsie, Schwangerschaft

Recurrent Spontaneous Abortion

Pregnancy loss, defined as spontaneous loss of the fetus before the end of the 24th week of gestation (GW), is the most common complication of pregnancy worldwide 1 . Around 15% of clinical pregnancies end by spontaneous abortion. It is estimated that almost every second woman will have at least one miscarriage during her reproductive years. Recurrent spontaneous abortion (RSA) is reported for around 1 – 5% of couples 2 . The figures vary, depending on the diagnostic criteria used to define RSA; while the WHO definition stipulates three or more consecutive miscarriages before the end of the 20th completed week of gestation 1 , the American guidelines define RSA as two failed intrauterine pregnancies 3 . Recurrent spontaneous abortion has a multifactorial pathogenesis which often remains unexplained 4 , and it represents a clinical challenge, both for the affected women and their treating physicians.

In addition to morphological, hormone-related and genetic causes, thrombophilic disorders have also been discussed as hemostatic risk factors for RSA. Thrombophilic disorders are a group of genetically determined or acquired hemostatic disorders which are associated with an increased propensity for venous thromboembolism (VTE). Antiphospholipid syndrome is considered to be a serious acquired thrombophilic disorder.

This review article examines the current body of literature on RSA in antiphospholipid syndrome and hereditary thrombophilias and the diagnostic and therapeutic recommendations in the German and international literature.

Complications of Pregnancy and Antiphospholipid Syndrome

Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is an autoantibody-mediated acquired thrombophilia of unclear etiology. Serologic criteria for APS include persistent detection of medium to high-titer autoantibodies against anionic phospholipids such as cardiolipin and β2-glycoprotein I or positive lupus anticoagulant (LA). The titer must be unambiguously positive when measured twice at an interval of at least 12 weeks between measurements, because infections and injuries etc. can temporarily lead to false-positive antibody results. Lupus anticoagulant can be false-positive following already initiated therapy with heparins, vitamin-K antagonists or the new oral anticoagulants 5 .

The Sydney classification criteria of 2006 state that in addition, at least one clinical criteria must be fulfilled for a diagnosis of APS to be made; clinical criteria can include thromboembolic events and defined complications of pregnancy ( Table 1 ) 6 . If all three serologic APS criteria (cardiolipin and β2-glycoprotein I antibodies as well as LA) are met, this is referred to as triple positivity. Patients with triple positivity have the highest risk of developing the clinical manifestation of APS. In some rare cases these autoantibodies are detected in the context of other autoimmune diseases, usually in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), which is then referred to as associated or secondary APS. If no underlying collagenosis is present, it is known as primary APS. The data on the relationship between primary and associated APS varies widely. Depending on the stringency of the diagnosis, up to 40% of APS patients also present with the clinical manifestations of SLE 7 .

Table 1 Classification criteria for antiphospholipid syndrome (based on 6 ).

| APS is diagnosed if at least one clinical and one laboratory criteria are met. |

| Clinical criteria |

|

| Laboratory criteria (present in plasma on two or more occasions measured at least 12 weeks apart) |

|

Irrespective of any VTE manifestations, up to 90% of patients with untreated APS had an obstetric history of miscarriage 7 , 8 . Particularly pregnancy losses in the second trimester of pregnancy and severe preeclampsia appear to be strongly associated with APS 9 , 10 . In addition to recurrent spontaneous abortion, APS is associated with a number of other complications of pregnancy which are characterized by disordered placental development and consequent functional placental insufficiency. This includes primarily late spontaneous abortions and intrauterine fetal death, intrauterine growth restriction of the fetus (IUGR), preeclampsia and premature placental separation. Because of the different classification criteria, study designs and investigated populations, it is difficult to estimate the incidence of these complications of pregnancy in APS.

Conversely, antiphospholipid antibodies or LA have been detected in around 6% of women with these complications of pregnancy 11 . The presence of lupus anticoagulant has been determined to be the most important risk factor 12 , 13 . The following factors for high-risk pregnancies were additionally identified:

previous VTE or complications of pregnancy in a previous pregnancy (OR 12.7),

triple positivity (OR 9.2), or

associated APS with clinically manifest SLE (OR 6.9) 13 .

Vaso-occlusive processes appear to be the underlying pathophysiological mechanism when APS is associated with complications of pregnancy. These processes can lead to macro and micro-thrombosis in the placental bed. But other mechanisms also play a pathophysiological role, particularly disorders of throphoblast differentiation and invasion with impairment of uteroplacental development 14 . The current hypotheses about the pathogenesis of APS-related complications of pregnancy are summarized in Table 2 (based on 15 ).

Table 2 Relevant pathogenetic mechanisms in APS-related complications of pregnancy (synopsis based on 15 ).

| TLR 4: Toll-like receptor 4; TNFα: tumor necrosis factor α; NF-κB: nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; IL1-β: interleukin 1 β; β-hCG: β-human chorionic gonadotropin; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor |

| Procoagulatory effects |

|

| Inflammatory effects |

|

| Direct effects on the placenta |

|

A number of different therapeutic concepts have been evaluated with regard to pregnancy outcomes and compared in a meta-analysis. The administration of glucocorticoids and intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG) did not result in any significant benefit in terms of the rate of live births. Only the combined administration of a prophylactic dose of low-dose acetylsalicylic acid (ASA, 75 – 100 mg/day) with heparin showed a benefit in terms of pregnancy outcomes in women with prior APS-related pregnancy loss 16 . Another meta-analysis carried out in 2010 confirmed the benefit of the combination therapy compared to monotherapy with ASA 17 . However, most data are from observational studies and there are no studies which directly compare heparin with ASA. The administration of ASA already prior to conception has been successfully used as prophylaxis against abortion in some case series 18 , and has been included in guideline recommendations 19 . When women at risk become pregnant, low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) is additionally administered. LMWH has some benefits compared to unfractionated heparin, including more reliable effective concentrations, fewer administrations required because of its longer half-life, and a lower risk of developing heparin-induced thrombopenia type II. However, care should be taken when administering LMWH to patients with impaired kidney function.

It has been suggested in this context that ASA and heparin have potential beneficial effects beyond simple anticoagulation such as inhibition of complement activation or the promotion of placental development 20 , 21 .

Particularly women with APS and triple positivity (see above) and a history of prior VTE may benefit from additional treatment strategies combined with ASA and heparin 22 . This was the conclusion of a retrospective analysis of 176 pregnant patients with APS, although only 13 of these pregnant women received additional treatment. It is unclear which of these additional therapies or combinations are effective in the respective setting. The additional administration of IVIG was the most commonly used therapy.

The use of hydroxychloroquine in addition to a combination of low-dose ASA and LMWH is recommended to treat pregnant women with SLE and associated APS. Although reliable data on the effect on primary APS are lacking, the additional administration of hydroxychloroquine is recommended for women who continue to suffer miscarriages despite a combination therapy with ASA and LMWH 23 .

The role of direct oral anticoagulants as a therapeutic option to treat APS has not yet been sufficiently evaluated 24 . Moreover, the use of direct oral anticoagulants is contraindicated in pregnancy.

For women with APS, pregnancy is a high-risk situation for mother and fetus. Irrespective of the chosen drug therapy, these women must be closely monitored and their care requires the interdisciplinary cooperation of specialists in obstetrics/gynecology, rheumatology and hemostaseology 19 .

Hereditary Thrombophilia and Recurrent Spontaneous Abortion

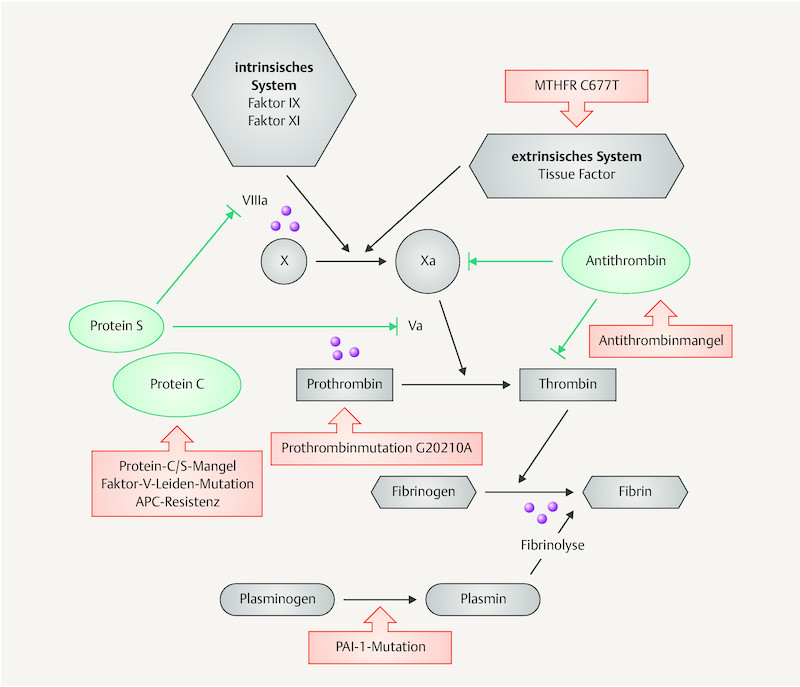

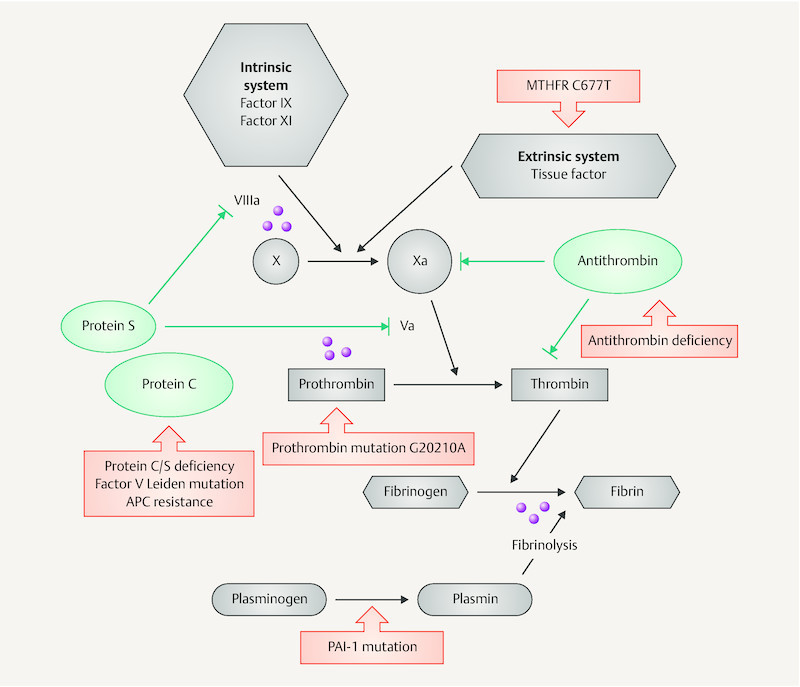

A number of genetic dispositions, most of which have an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, have been identified as risk factors for developing VTE. These congenital thrombophilias include inhibitor deficiencies (antithrombin, protein C and protein S deficiency), activated protein C resistance based on factor V Leiden mutation and the prothrombin gene (G20210A) mutation. Mutations of fibrinolysis factors (t-PA, PAI-1 and factor VII activating protease [FSAP]) and associated hyperhomocysteinemia caused by MTHFR C677T mutation are associated with a significantly lower risk of VTE. Fig. 1 schematically illustrates some of the risk factors associated with hereditary thrombophilia which are relevant for the coagulation cascade (based on 25 ).

Fig. 1.

Plasmatic coagulation, fibrinolysis and thrombophilia (modified according to 25 ). Activation of the coagulation cascade via extrinsic or intrinsic systems leads to factor X activation. This then leads to cleavage of factor II (prothrombin) and to the development of thrombin. Antithrombin and protein C/S function here as inhibitory factors (indicated in green in the illustration). Red identifies the most common types of hereditary thrombophilia. Pink circles stand for potential thrombophilic mechanisms in APS (e.g. through interactions of the antibodies with factor X or prothrombin; inhibition of fibrinolysis). In addition (not shown here), the activation of endothelial cells and thrombocytes play a pathogenetic role in APS. MTHFR C677T: methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase polymorphism, APC: activated protein C, PAI-1: plasminogen activator inhibitor-1.

The incidence of these mutations worldwide differs between ethnic groups, resulting in differences in the propensity for thrombogenicity. Based on epidemiological studies it is currently assumed that up to 15% of the Caucasian population have one of the above-mentioned thrombophilic disorders, of which the heterozygous factor V R506Q mutation (also known as factor V Leiden mutation [FVL]) is the most common with 5%. Heterozygous prothrombin (G20210A) gene mutation (PGM) is the second most common mutation and is found in around 2 – 4% of the Caucasian population 26 .

Two meta-analyses, carried out in 2003 and 2006 respectively, evaluated data from 31 and 79 mostly retrospective case control studies of hereditary thrombophilia and RSA 27 , 28 . The analyses of the association between individual genetic thrombophilias and total RSA, RSA in the 1st trimester of pregnancy and non-recurrent late fetal loss are shown in Table 3 and compared with antiphospholipid antibodies. The heterogeneity of the data was due to differences in the definition of RSA and the study populations (e.g. week of gestation on inclusion in the study, population size, and ethnicity). An association with RSA has been reported for FVL (pooled for homozygous and heterozygous) and heterozygous PGM, the most common mutations occurring in Caucasian populations. However this risk is lower than that associated with APS. A meta-analysis, carried out in 2010 which only included prospective studies, calculated the pooled odds ratio for all pregnancy losses of women with FVL (absolute risk 4.2%) compared to healthy controls (absolute risk 3.2%) as 1.5 (95% CI: 1.05 – 2.19) 29 . Patients with antithrombin and protein C deficiency and homozygous MTHFR 677T mutation do not appear to have an increased risk of RSA.

Table 3 Thrombophilia and risk of RSA based on meta-analyses.

| Thrombophilia | RSA overall | RSA in the 1st trimester | Non-recurrent miscarriage in the 2nd trimester | Non-recurrent late miscarriage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The confidence interval for the odds ratio was set at 95%. RSA: recurrent spontaneous abortion; late miscarriage = pooled miscarriages after the 10th 10 , 20th 27 or 24th GW 28 ; FVL: factor V Leiden mutation; PGM: prothrombin gene (G20210A) mutation; MTHFR: methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase C677T mutation; APC resistance: active protein C resistance. Anticardiolipin antibodies: IgG 13 , 28 , IgG/IgM 10 . β2-glycoprotein I antibodies: IgG 13 , IgG/IgM 10 . | |||||

| Lupus anticoagulant | 15.42 (5.90 – 40.38) 13 | n. s. | 14.28 (4.72 – 43.20) 28 | 2.30 (0.81 – 6.98) 28 | 10.59 (1.87 – 59.88) 10 |

| Anticardiolipin antibodies | 3.57 (2.26 – 5.65) 13 | 5.05 (1.92 – 14.01) 28 | n. s. | 3.30 (1.62 – 6.70) 28 | 4.29 (1.34 – 13.68) 10 |

| β2-glycoprotein I antibodies | n. s. | 2.12 (0.69 – 6.53) 13 | n. s. | 23.46 (1.21 – 455.01) 10 | |

| FVL (homozygous and heterozygous) | 3.04 (2.16 – 4.3) 27 | 1.91 (1.01 – 3.61) 28 | 4.12 (1.93 – 8.81) 28 | 3.26 (1.82 – 5.83) 27 | 2.06 (1.1 – 3.86) 28 |

| Heterozygous PGM G20210A | 2.05 (1.18 – 3.54) 27 | 2.70 (1.37 – 5.34) 28 | 8.6 (2.18 – 33.95) 28 | 2.3 (1.09 – 4.87) 27 | 2.66 (1.28 – 5.53) 28 |

| Protein S deficiency | 14.72 (0.99 – 218.01) 27 | n. s. | n. s. | 7.39 (1.28 – 42.83) 27 | 20.09 (3.7 – 109.15) 28 |

| Protein C deficiency | 1.57 (0.23 – 10.54) 27 | n. s. | n. s. | 3.05 (0.24 – 38.51) 27 | |

| Antithrombin deficiency | 0.88 (0.17 – 4.48) 27 | n. s. | n. s. | 7.63 (0.30 – 196.36) 28 | |

| Homozygous MTHFR 677 T | 0.98 (0.55 – 1.72) 27 | 0.96 (0.44 – 1.69) 28 | n. s. | 1.31 (0.89 – 1.91) 28 | |

| APC resistance | n. s. | 2.60 (1.21 – 5.59) 28 | n. s. | 0.98 (0.17 – 5.55) 28 | |

It should be noted that, because of their rarity, there are almost no data available for significantly rarer and highly thrombophilic constellations such as homozygous mutations (both FVL mutation and PGM G20210A) or complex combined hereditary thrombophilia. The current body of data on the association between late miscarriages (after the 24th GW) and the presence of antithrombin or protein C deficiency is also insufficient.

In addition to the risk of miscarriage a correlation between hereditary thrombophilia and other placenta-related complications is also currently being discussed 29 , 30 . The available data are shown in Table 4 .

Table 4 Thrombophilia and placenta-related complications of pregnancy based on meta-analyses.

| Thrombophilia | Preeclampsia | Premature placental separation | Growth retardation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The confidence interval for the odds ratio was set at 95%. FVL: factor V Leiden mutation; PGM: prothrombin gene (G20210A) mutation; MTHFR: methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase C677T mutation; APC resistance: activated protein C resistance. Anticardiolipin antibodies: IgG/IgM

10

, not specified

28

.

n. s.: not specified; * pooled data for homozygous and heterozygous forms | ||||||

| Lupus anticoagulant | 1.45 (0.70 – 4.61) 28 | 2.34 (1.18 – 4.64) 10 | 0.26 (0.01 – 4.56) 10 | 4.65 (1.29 – 16.71) 10 | ||

| Anticardiolipin antibodies | 2.73 (1.65 – 4.51) 28 | 1.52 (1.05 – 2.20) 10 | 1.42 (0.42 – 4.77) 28 | 1.30 (0.35 – 4.78) 10 | 6.91 (2.70 – 17.68) 28 | 1.97 (0.19 – 19.96) 10 |

| Anti-β2 GP1 IgG/IgM antibodies | 19.14 (6.34 – 57.77) 10 | 2.64 (0.14 – 50.63) 10 | 20.03 (4.59 – 87.43) 10 | |||

| FVL (homozygous) | 1.87 (0.44 – 7.88) 28 | 1.23 (0.89 – 1.70)* 29 | 8.43 (0.41 – 171.20) 28 | 1.85 (0.92 – 3.70)* 29 | 4.64 (0.19 – 115.68) 28 | 1.00 (0.80 – 1.25)* 29 |

| FVL (heterozygous) | 2.19 (1.46 – 3.27) 28 | 1.23 (0.89 – 1.70)* 29 | 4.70 (1.13 – 19.59) 28 | 1.85 (0.92 – 3.70)* 29 | 2.68 (0.59 – 12.13) 28 | 1.00 (0.80 – 1.25)* 29 |

| Heterozygous PGM G20210A | 2.54 (1.52 – 4.23) 28 | 1.25 (0.79 – 1.99) 29 | 7.71 (3.01 – 19.76) 28 | 2.02 (0.81 – 5.02) 29 | 2.92 (0.62 – 13.70) 28 | 1.25 (0.92 – 1.70) 29 |

| Protein C deficiency | 5.15 (0.26 – 102.22) 28 | 5.93 (0.23 – 151.58) 28 | n. s. | |||

| Protein S deficiency | 2.83 (0.76 – 10.57) 28 | 2.11 (0.47 – 9.34) 28 | n. s. | |||

| Antithrombin deficiency | 3.89 (0.16 – 97.19) 28 | 1.08 (0.06 – 18.12) 28 | n. s. | |||

| Homozygous MTHFR 677 T | 1.37 (1.07 – 1.76) 28 | 1.47 (0.40 – 5.35) 28 | 1.24 (0.84 – 1.82) 28 | |||

| APC resistance | n. s. | 2.60 (1.21 – 5.59) 28 | 0.98 (0.17 – 5.55) 28 | |||

The first studies on the prophylactic administration of heparin to women with hereditary thrombophilia and RSA appeared to be promising based on the rate of live births. But these results, which were predominantly obtained from observational studies, were not confirmed by recently carried out prospective randomized controlled studies. A meta-analysis of data from randomized controlled studies was recently published 31 . In their meta-analysis, Skeith et al. analyzed the pooled data of 483 pregnant women with different types of hereditary thrombophilia evaluated in eight prospective randomized controlled studies, some of which were also placebo controlled. No difference was found with regard to the reduction of late pregnancy losses (defined as loss after 10th GW, level of evidence 1b) or recurrent early pregnancy losses (defined as > 2 pregnancy losses before the 10th GW, level of evidence 2b) between women who received LMWH and those who did not. This meta-analysis also has some limitations, mainly due to the heterogeneous design of the studies included in the meta-analysis, the inconsistent definitions of RSA in the individual studies and the inconsistent differentiation between early and late pregnancy loss. Some of the studies used ASA in the control arm, and it is therefore not possible to exclude the possibility that ASA was a confounding variable. Rare homozygous or combined gene variants are also underrepresented in this study. Researchers are awaiting the results of other prospective randomized controlled studies such as the currently ongoing ALIFE2 trial 32 to evaluate the body of evidence and resolve some of the open issues.

The results of a meta-analysis published in 2016 on recurrent placenta-related complications and the prophylactic administration of heparin were similar. The evaluation of a total of 401 patients with genetic thrombophilia did not find a general benefit from administering LMWH 33 . Only a subgroup analysis of patients with premature placental separation showed a benefit for the prophylactic use of LMWH. The cohorts, both from single-center and multicenter studies, were also extremely heterogeneous.

There is a clear recommendation that patients with a prior history of preeclampsia or fetuses with intrauterine growth retardation should receive prophylactic ASA, irrespective of any underlying maternal thrombophilia 34 . According to more recent data, the risk of preeclampsia can be reduced by commencing ASA intake as soon as possible (before the 16th week of pregnancy) and administering ASA doses of at least 100 mg/day 35 . But the administration of ASA is not generally recommended as a prophylaxis against spontaneous abortion 36 . Further studies will be needed in future to determine to what extent ASA has a dose-dependent effect on women known to have APS.

National and International Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Prophylactic Treatment of Pregnancy Loss due to RSA and Maternal Thrombophilia

The data collected over the last decade are controversial and the recommendations issued by various international guidelines show similar differences. A comparison of German 37 , American 38 and British 39 guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of RSA and thrombophilia is shown in Table 5 . These guidelines were compiled between 2011 and 2015 and represent the consensus of various panels of experts; the reported levels of evidence correspond to the data available at the respective time of compilation.

Table 5 Comparison of recommendations in the most recent German, American and British guidelines on RSA (< 20th week of pregnancy) and maternal thrombophilia without prior VTE.

| RSA without VTE | German guideline 37 | American guideline 38 | British guideline 39 |

|---|---|---|---|

| RSA: recurrent spontaneous abortion; VTE: venous thromboembolism; LA: lupus anticoagulant; AT activity: antithrombin activity; APC resistance: anti-protein C resistance; FVL: factor V Leiden mutation; PGM: prothrombin gene (G20210A) mutation; APS: antiphospholipid syndrome; LMWH: low molecular weight heparin | |||

| Screening for APS (LA, anticardiolipin antibodies IgG and IgM, anti-β2 GP1 antibodies IgG and IgM) | Yes | Yes (level of evidence 1B) | Yes (level of evidence D) |

| Screening for hereditary thrombophilia | AT activity, APC resistance/FVL, PGM | No (level of evidence 2C) | Only if the reason for pregnancy loss from the 2nd trimester is unclear: FVL, PGM, protein S deficiency (level of evidence D) |

| Prophylactic administration of medication | |||

| Hereditary thrombophilia | No administration outside clinical studies | No (level of evidence 2C) | LMWH for pregnancy losses from the 2nd trimester (level of evidence A) |

| APS | Low-dose ASA and LMWH | Low-dose ASA and LMWH (level of evidence 1B) | Low-dose ASA and LMWH (level of evidence B) |

All of the recommendations are agreed that in the event of RSA and other complications of pregnancy as defined by the APS classification criteria, affected women should be screened for antiphospholipid antibodies and LA. For women with a confirmed diagnosis of APS, the recommendation is to administer low-dose ASA and a prophylactic dose of LMWH from the time of the positive pregnancy test until at least 6 weeks post partum.

The guidelines unanimously reject any general prophylactic administration of LMWH to treat 1st trimester RSA due to maternal hereditary thrombophilia. As regards pregnancy losses from the 2nd trimester of pregnancy, the British guideline recommends investigating the patient to determine whether any hereditary thrombophilia is present as well as the prophylactic use of LMWH. The latter recommendation is not sufficiently supported by the meta-analysis published in 2016 31 . A general diagnostic work-up for maternal hereditary thrombophilia in case of RSA will no longer be recommended in the soon-to-be-published update of the German guideline (personal communication, E. Schleußner).

VTE Prophylaxis for Maternal Thrombophilia in Pregnancy

From a hemostaseological perspective, pregnancy is per se a physiological condition of increased procoagulatory activity. The risk of pregnant women developing VTE is 5 times higher throughout the entire pregnancy compared to non-pregnant women; the risk is 20-fold higher in the postnatal period 40 . Delivery by C-section additionally increases the risk of VTE between 2- and 4-fold compared to vaginal delivery 41 . In industrialized countries, the incidence of pulmonary embolism is 1 – 1.5 per 100 000 births, making it the most common cause of maternal death post partum 42 . Women receiving hormones (e.g., for reproductive treatment) have a generally increased risk of VTE.

Irrespective of recurrent pregnancy losses or other complications of pregnancy the individual maternal risk of VTE (disposition and exposition) determines whether or not drug treatment as prophylaxis against thrombosis is necessary and therefore whether heparin administration is indicated during pregnancy. Important factors for an increased risk of VTE include prior VTE or a positive familial history of VTE, certain complications of pregnancy such as exsiccosis/hyperemesis, hospitalization, assisted reproduction, and overweight. The AWMF S3 guideline recommends heparin therapy during pregnancy, particularly when highly thrombophilic mutations (homozygous FVL mutation, antithrombin deficiency, complex combined variants) are present, because of the increased maternal risk of VTE 41 .

Table 6 summarizes decision-making on the use of low molecular weight heparin to treat pregnant patients with thrombophilia.

Table 6 Recommendation for LMWH administration during pregnancy if maternal thrombophilia is present.

| Recurrent early pregnancy loss/late pregnancy loss | Increased maternal risk for VTE | |

|---|---|---|

| LMWH: low molecular weight heparin; VTE: venous thromboembolism; APS: antiphospholipid syndrome. 1 During pregnancy, blood pressure, proteinuria and maternal weight from the 16th–20th GW must be monitored along with monthly monitoring of fetal growth and placental perfusion. Osteoporosis prophylaxis must be combined with monitoring thrombocyte counts during LMWH treatment in accordance with the AWMF S3 guideline 41 (between the 5th to 15th day after the start of LMWH; a drop of the thrombocyte count to less than 50% of the initial count is suspicious for heparin-induced thrombopenia type IIa, which would necessitate the immediate cessation of heparin therapy). | ||

| Hereditary thrombophilia | No | Yes |

| APS | 75 – 100 mg ASA/day, optimally initiated before conception, combined with LMWH from the time of a positive pregnancy test until 6 weeks post partum 1 | |

Conclusion

Screening for antiphospholipid antibodies including LA is recommended in cases with recurrent spontaneous abortion and/or placenta-related complications of pregnancy. APS is a serious acquired thrombophilia and represents a clear indication for the administration of low-dose ASA prior to conception combined with prophylactic doses of LMWH from the start of pregnancy (level of evidence 1b).

Based on the currently available studies, recurrent spontaneous abortion in women with maternal hereditary thrombophilia is not an indication for the prophylactic administration of LMWH in subsequent pregnancies (level of evidence 2b for RSA < 10th GW, 1b for pregnancy losses after the 10th GW).

According to the current guidelines, the maternal risk for thromboembolic events determines whether non-drug-based or drug-based VTE prophylaxis is indicated, e.g. with low molecular weight heparin. In addition to maternal disposition, other VTE factors such as immobilization, hospitalization, dehydration due to hyperemesis, assisted reproduction or overweight are also clinically relevant for the assessment of maternal risk and the decision whether VTE prophylaxis is indicated. Based on the currently available data, there is insufficient evidence that women who have recurrent spontaneous abortion should undergo broad screening for hereditary thrombophilia.

Interdisciplinary cooperation between specialists in obstetrics/gynecology, rheumatology and hemostaseology is important to ensure optimal management of patients.

Conflict of Interest/Interessenkonflikt The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Die Autoren geben an, dass kein Interessenkonflikt besteht.

Shared last authorship

geteilte Letztautorenschaft

References/Literatur

- 1.WHO . Recommended definitions, terminology and format for statistical tables related to the perinatal period and use of a new certificate for cause of perinatal deaths. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1977;56:247–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rai R, Regan L. Recurrent miscarriage. Lancet. 2006;368:601–611. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine . Definitions of infertility and recurrent pregnancy loss: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2013;99:63. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine . Evaluation and treatment of recurrent pregnancy loss: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:1103–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Specker C. Antiphospholipid syndrome. Z Rheumatol. 2016;75:570–574. doi: 10.1007/s00393-016-0153-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miyakis S, Lockshin M D, Atsumi T. International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:295–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cervera R, Piette J C, Font J. Antiphospholipid syndrome: clinical and immunologic manifestations and patterns of disease expression in a cohort of 1,000 patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:1019–1027. doi: 10.1002/art.10187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rai R, Clifford K, Cohen H. High prospective fetal loss rate in untreated pregnancies of women with recurrent miscarriage and antiphospholipid antibodies. Hum Reprod. 1995;10:3301–3304. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a135907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chighizola C B, Andreoli L, de Jesus G R. The association between antiphospholipid antibodies and pregnancy morbidity, stroke, myocardial infarction, and deep vein thrombosis: a critical review of the literature. Lupus. 2015;24:980–984. doi: 10.1177/0961203315572714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abou-Nassar K, Carrier M, Ramsay T. The association between antiphospholipid antibodies and placenta mediated complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb Res. 2011;128:77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andreoli L, Chighizola C B, Banzato A. Estimated frequency of antiphospholipid antibodies in patients with pregnancy morbidity, stroke, myocardial infarction, and deep vein thrombosis: a critical review of the literature. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013;65:1869–1873. doi: 10.1002/acr.22066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yelnik C M, Laskin C A, Porter T F. Lupus anticoagulant is the main predictor of adverse pregnancy outcomes in aPL-positive patients: validation of PROMISSE study results. Lupus Sci Med. 2016;3:e000131. doi: 10.1136/lupus-2015-000131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Opatrny L, David M, Kahn S R. Association between antiphospholipid antibodies and recurrent fetal loss in women without autoimmune disease: a metaanalysis. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:2214–2221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Viall C A, Chamley L W. Histopathology in the placentae of women with antiphospholipid antibodies: a systematic review of the literature. Autoimmun Rev. 2015;14:446–471. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2015.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ostensen M, Andreoli L, Brucato A. State of the art: reproduction and pregnancy in rheumatic diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2015;14:376–386. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2014.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Empson M, Lassere M, Craig J. Prevention of recurrent miscarriage for women with antiphospholipid antibody or lupus anticoagulant. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(02):CD002859. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002859.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mak A, Cheung M W, Cheak A A. Combination of heparin and aspirin is superior to aspirin alone in enhancing live births in patients with recurrent pregnancy loss and positive anti-phospholipid antibodies: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and meta-regression. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010;49:281–288. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bouvier S, Cochery-Nouvellon E, Lavigne-Lissalde G. Comparative incidence of pregnancy outcomes in treated obstetric antiphospholipid syndrome: the NOH-APS observational study. Blood. 2014;123:404–413. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-08-522623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andreoli L, Bertsias G K, Agmon-Levin N. EULAR recommendations for womenʼs health and the management of family planning, assisted reproduction, pregnancy and menopause in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and/or antiphospholipid syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:476–485. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Girardi G, Redecha P, Salmon J E. Heparin prevents antiphospholipid antibody-induced fetal loss by inhibiting complement activation. Nat Med. 2004;10:1222–1226. doi: 10.1038/nm1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alvarez A M, Balcázar N, San Martín S. Modulation of antiphospholipid antibodies-induced trophoblast damage by different drugs used to prevent pregnancy morbidity associated with antiphospholipid syndrome. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2017;77:e12634. doi: 10.1111/aji.12634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruffatti A, Salvan E, Del Ross T. Treatment strategies and pregnancy outcomes in antiphospholipid syndrome patients with thrombosis and triple antiphospholipid positivity. A European multicentre retrospective study. Thromb Haemost. 2014;112:727–735. doi: 10.1160/TH14-03-0191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sciascia S, Branch D W, Levy R A. The efficacy of hydroxychloroquine in altering pregnancy outcome in women with antiphospholipid antibodies. Evidence and clinical judgment. Thromb Haemost. 2016;115:285–290. doi: 10.1160/TH15-06-0491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen H, Hunt B J, Efthymiou M. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin to treat patients with thrombotic antiphospholipid syndrome, with or without systemic lupus erythematosus (RAPS): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 2/3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Haematol. 2016;3:e426–e436. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(16)30079-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Willeke A, Gerdsen F, Bauersachs R M. Rationelle Thrombophiliediagnostik. Deutsches Ärzteblatt. 2002;31 – 32:2111–2118. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roberts L N, Patel R K, Arya R. Venous thromboembolism and ethnicity. Br J Haematol. 2009;146:369–383. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rey E, Kahn S R, David M. Thrombophilic disorders and fetal loss: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2003;361:901–908. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12771-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robertson L, Wu O, Langhorne P. Thrombophilia in pregnancy: a systematic review. Br J Haematol. 2006;132:171–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rodger M A, Betancourt M T, Clark P. The association of factor V Leiden and prothrombin gene mutation and placenta-mediated pregnancy complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000292. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baumann K, Beuter-Winkler P, Hackethal A. Maternal factor V Leiden and prothrombin mutations do not seem to contribute to the occurrence of two or more than two consecutive miscarriages in Caucasian patients. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2013;70:518–521. doi: 10.1111/aji.12144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Skeith L, Carrier M, Kaaja R. A meta-analysis of low-molecular-weight heparin to prevent pregnancy loss in women with inherited thrombophilia. Blood. 2016;127:1650–1655. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-12-626739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Jong P G, Quenby S, Bloemenkamp K W. ALIFE2 study: low-molecular-weight heparin for women with recurrent miscarriage and inherited thrombophilia–study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2015;16:208. doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-0719-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rodger M A, Gris J C, de Vries J IP. Low-molecular-weight heparin and recurrent placenta-mediated pregnancy complications: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2016;388:2629–2641. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31139-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bujold E, Roberge S, Lacasse Y. Prevention of preeclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction with Aspirin started in early pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:402–414. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181e9322a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roberge S, Nicolaides K, Demers S. The role of aspirin dose on the prevention of preeclampsia and fetal growth restriction: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216:110–1.2E8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.09.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schisterman E F, Silver R M, Lecher L L. Preconception low-dose aspirin and pregnancy outcomes: results from the EAGeR randomised trial. Lancet. 2014;384:29–36. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60157-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Toth B, Würfel W, Bohlmann M K. Recurrent miscarriage: diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. Guideline of the DGGG (S1-Level, AWMF Registry No. 015/050, December 2013) Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 2015;75:1117–1129. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1558299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bates S M, Greer I A, Middeldorp S. VTE, thrombophilia, antithrombotic therapy, and pregnancy: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:e691S–e736S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gynaecologists, RCOG The investigation and treatment of couples with recurrent firsttrimester and second-trimester miscarriage. RCOG Green-top Guideline No. 17, 2011Last update April2011. Online:http://www.nice.org.uk/accreditation

- 40.Heit J, Kobbervig C E, James A H. Trends in the incidence of venous thromboembolism during pregnancy or postpartum: a 30-year population-based study. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:697–706. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-10-200511150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Encke A, Haas S, Kopp I.S3-Leitlinie Prophylaxe der venösen Thromboembolie (VTE) AWMF; 2015. Onlinehttp://www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/003-001.htmlStand 15.10.2015

- 42.Marik P E, Plante L A. Venous thromboembolic disease and pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2025–2033. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0707993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]