Abstract

Complex posttraumatic stress disorder (Complex PTSD) has been recently proposed as a distinct clinical entity in the WHO International Classification of Diseases, 11th version, due to be published, two decades after its first initiation. It is described as an enhanced version of the current definition of PTSD, with clinical features of PTSD plus three additional clusters of symptoms namely emotional dysregulation, negative self-cognitions and interpersonal hardship, thus resembling the clinical features commonly encountered in borderline personality disorder (BPD). Complex PTSD is related to complex trauma which is defined by its threatening and entrapping context, generally interpersonal in nature. In this manuscript, we review the current findings related to traumatic events predisposing the above-mentioned disorders as well as the biological correlates surrounding them, along with their clinical features. Furthermore, we suggest that besides the present distinct clinical diagnoses (PTSD; Complex PTSD; BPD), there is a cluster of these comorbid disorders, that follow a continuum of trauma and biological severity on a spectrum of common or similar clinical features and should be treated as such. More studies are needed to confirm or reject this hypothesis, particularly in clinical terms and how they correlate to clinical entities’ biological background, endorsing a shift from the phenomenologically only classification of psychiatric disorders towards a more biologically validated classification.

Keywords: Complex posttraumatic stress disorder, Posttraumatic stress disorder, Borderline personality disorder, Trauma, Complex trauma

Core tip: A cluster of complex posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), PTSD and borderline personality disorder that have in common a history of trauma, is proposed, as a clinical and biological continuum of symptom severity, to be classified together under trauma-related disorders instead of just distinct clinical diagnoses. Trauma depending on biological vulnerability and other precipitating risk factors is suggested that it can lead to either what we commonly diagnose as PTSD or to profound and permanent personality changes, with complex PTSD being an intermediate in terms of its clinical presentation and biological findings so far.

INTRODUCTION

Complex posttraumatic stress disorder (Complex PTSD), has been originally proposed by Herman[1], as a clinical syndrome following precipitating traumatic events that are usually prolonged in duration and mainly of early life onset, especially of an interpersonal nature and more specifically consisting of traumatic events taking place during early life stages (i.e., child abuse and neglect)[1].

In order to develop a new psychiatric diagnosis, it requires carrying a certain extent of validity as a distinct entity with a clinical utility[2], providing essential additions to already established diagnoses especially regarding biological aetiology, course and treatment options.

Several psychiatric disorders overlap in terms of symptomatology and there is a high comorbidity present to most, if not all, especially when precipitating factors are common or similar. Furthermore, until now, psychiatric diagnoses have been traditionally described as theoretical constructs, mostly to facilitate communication of professionals working in the field, with the exact psychopathological processes and biological background research only currently blooming. This also carries the question whether already established psychiatric diagnoses need to be re-evaluated and re-grouped following newly suggested research findings, aiming to offer more efficient treatment plans to patients in question.

It has been questioned[2,3] whether complex PTSD can form a distinct diagnosis, since its symptomatology often overlaps with several mental disorders following trauma, mainly with PTSD which is usually correlated to single event trauma as well as Axis II disorders, mainly borderline personality disorder (BPD). The latter besides the high comorbidity with complex PTSD[4], also shares some of the core symptoms described in complex PTSD especially related to impaired relationships with others, dissociative symptoms, impulsive or reckless behaviours, irritability and self-destructive behaviours.

Complex PTSD is defined by symptom clusters mainly resembling an enhanced PTSD, with symptoms such as shame, feeling permanently damaged and ineffective, feelings of threat, social withdrawal, despair, hostility, somatisation and a diversity from the previous personality. It also regularly presents with serious disturbances in self-organisation in the form of affective dysregulation, consciousness, self-perception with a negative self-concept and perception of the penetrator(s), often causing dysfunctional relations with others leading to interpersonal problems[1,5-7].

The aim of this paper is to review the until now research on complex PTSD and its correlation to other trauma-related mental disorders mainly PTSD and BPD, primarily regarding the diagnostic frame and biological correlates, in order to examine whether there is sufficient data to approve the need of establishing a distinct clinical mental syndrome or to address the need to reassess and expand the diagnostic criteria of trauma-related disorders to include clinical features of complex PTSD currently missing from the already confirmed clinical entities.

CLINICAL DESCRIPTIONS AND BIOLOGICAL CORRELATES OF COMPLEX PTSD, PRECIPITATING TRAUMATIC EVENTS AND CLINICAL DIVERGENCE FROM PTSD

Complex PTSD is already suggested as a distinct diagnostic entity, in the World Health Organization (WHO) International Classification of Diseases, 11th version, (ICD-11)[5], which is due to be published in 2018 and currently under review, classified under disorders specifically associated with stress. It is grouped together along with PTSD, prolonged grief disorder, adjustment disorder, reactive attachment disorder, disinhibited social engagement disorder and others. The disorders mentioned above are all associated with stress and exposure to distressing traumatic events. The clinical features following the stressful experience result in serious functional impairment regardless whether the traumatic event precipitating the disorder, falls under the normal range of life experiences (such as grief) or encompasses events of a menacing nature (i.e., torture or abuse).

According to ICD-11[5], complex PTSD follows exposure to a traumatic event or a series of events of an extremely threatening nature most commonly prolonged, or repetitive and from which escape is usually impossible or strenuous[6].

Two decades ago when it was first proposed, precipitating traumatic events were described strictly as being prolonged in time usually taking place during early developmental stages (i.e., childhood)[1]. The literature describing complex PTSD ever since, following its first initiation as a cluster of symptoms beyond classic PTSD, began to also include entrapping events taking place during adulthood[8] and argued against their prolonged nature per se, referring to single event traumas as well as repeated series of single complex trauma that could be so severe and catastrophic in nature leading to profound personal effects, such as personality modification, even after the conclusion of major developmental stages[9]. A recent study of Palic et al[10], argues of the complex PTSD association, not only with childhood trauma but with exposure to all forms of adulthood trauma, predominately having in common the interpersonal intensity of the stress induced and the severity of prolonged trauma exposure. Another study of va Dijke et al[11], correlated the presence of complex trauma in adulthood to complex PTSD symptomatology, specifically dissociation, suggesting a potential link to the dissociative subtype of PTSD.

Complex trauma, which summates a total of precipitating traumatic events to complex PTSD, is currently being described as a horrific, threatening, entrapping, deleterious and generally interpersonal traumatic event, such as prolonged domestic violence, childhood sexual or physical abuse, torture, genocide campaigns, slavery etc. along with the victim’s inability to escape due to multiple constraints whether these are social, physical, psychological, environmental or other[12,13].

Complex PTSD includes most of the core symptoms of PTSD, specifically flashbacks (i.e., re-experiencing the traumatic event), numbness and blunt emotion, avoidance and detachment from people, events and environmental triggers of the predisposing trauma as well as autonomic hyperarousal. Furthermore, due to the nature of the complex trauma experienced, it also includes affective dysregulation, adversely disrupted belief systems about oneself as being diminished and worthless, severe hardship in forming and maintaining meaningful relationships along with deep-rooted feelings of shame and guilt or failure[7]. Its distinct characteristics added upon PTSD symptomatology, often interfere to separate it from BPD (i.e., affective dysregulation) and PTSD alone, which in cases with a chronic course will eventually transit to a lasting personality change[14].

Therefore it is speculated that prolonged exposure to complex trauma and/or chronic PTSD, would, therefore, lead to personality alterations that are often also seen clinically in complex PTSD patients (such as feelings of being permanently damaged and alienation), even when the traumatic experiences are taking place during adulthood[14]. It is speculated that complex trauma has to be present for a sufficient amount of time to cause a clinically evident diversion from the already established personality traits, towards traits that seem to either help the victim cope with trauma or as an expression of disintegration which might express as the dysregulation of emotion processing and self-organisation, two of the core symptoms added to the already established PTSD diagnostic criteria[10,15]. Complex trauma, especially childhood cumulative trauma and exposure to multiple or repeated forms of maltreatment, has been shown to affect multiple affective and interpersonal domains[12]. Also, chronic trauma is more strongly predictive of complex PTSD than PTSD alone, while complex PTSD is associated with a greater impairment in functioning[16].

Up to now, there is a lack of investigation of biological correlates to complex PTSD, referring to neuroimaging studies, autonomic and neurochemical measures and genetic predisposition[17]. The only data so far, consist of neuroimaging studies mainly in groups of child abuse-related subjects that mostly argue for the hippocampal dysfunction and decreased gray matter density observed, activation disturbances in the prefrontal cortex[18-20], as well as findings suggesting of more a severe neural imaging correlate in complex PTSD than those observed in PTSD patient studies, primarily involving brain areas related to emotional regulation and cognitive defects, symptoms that have been additionally added in complex PTSD symptomatology vs PTSD[17]. Structural brain abnormalities in complex PTSD seem to be more extensive with brain activity after complex trauma being distinctive than the one seen in PTSD patients who had experienced only single trauma[21] with higher functional clinical impairment in complex PTSD independently described but confirming the biological results mentioned above[22,23].

The three additional clusters of symptoms beyond core PTSD symptoms refer to emotional regulation, negative self-concept and interpersonal relational dysfunction[24].

PTSD has been re-evaluated in DSM-5[15], adding a cluster D of PTSD symptoms including altering in mood and cognition following the traumatic experience, as well as the dissociative PTSD subtype (i.e., depersonalisation and/or derealisation), a subtype that clinically resembles the cluster of symptoms that are commonly encountered in the complex PTSD[25]. A recent study of Powers et al[26] though, concluded that the ICD-11 Complex PTSD diagnosis is different than the DSM-5 PTSD diagnosis, in all clinical domains, showing more severe emotion regulation and dissociation, and more severe impairment in relational attachment, suggesting that they present two distinct constructs. More studies are needed to investigate the biological basis of complex PTSD as a clinical entity and its differences from trauma-induced disorders such as PTSD.

RE-CONCEPTUALISING BPD AS A COMPLEX TRAUMA SPECTRUM DISORDER

BPD is characterized by emotional dysregulation, oscillating between emotional inhibition and extreme emotional lability which has been often associated with prolonged childhood trauma[27], such as child abuse and neglect as well as adverse childhood experiences, present in a range within 30 to 90% of BPD patients[28-30]. Emotional dysregulation, an unstable sense of identity, difficulties in interpersonal relationships as core features of BPD[15] and precipitating complex interpersonal traumatic victimisation, a cluster of symptoms that overlaps with symptomatology described in complex PTSD, has led into a series of arguments whether BPD represents a comorbidity of trauma-related disorders or it actually duplicates complex PTSD, a clinical entity already introduced as a separate trauma-related diagnosis in ICD-11[31].

The WHO International Classification of Diseases, 11th version, (ICD-11), includes a slightly different spectrum of personality disorders classification, including BPD into a wider spectrum of the Emotionally Unstable Personality Disorder, carrying all of the characteristics that BPD has been known by, so far, but distinguishing two types; the impulsive type, defined by emotional instability and impulsiveness and the borderline type with an unstable sense of self and the environment, self-destructive tendencies and intense and unstable relations. Still again, while traumatic stress exposure is fundamental in Complex PTSD and has been added to its diagnostic criteria, it is not included in the definition of BPD, albeit the multiple references that trauma, especially during early life stages, plays a crucial role in the development of the borderline personality even if epigenetically added upon a temperamental vulnerability[32]. Especially childhood trauma such as, sexual and physical abuse, maladaptive parenting, neglect, and parental conflict has been correlated to BPD multiple times in literature as risk if not etiological factors[33].

The long-term stress response mechanism activation, mediated by the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, due to chronic stress exposure, can predispose to multiple stress-related psychiatric entities, including PTSD[34]. Stress early in life due to childhood trauma has been reported to result in an adjustment dysfunction of the HPA axis responsiveness upon stress states encountered, with patients with BPD. There seems to be an increased activation of the HPA axis[35,36], suggesting the association of the main stress regulating mechanism to childhood trauma and a biological correlation to the development of the borderline personality. Furthermore, several interacting neurotransmitter systems are shown to be affected in BPD[37,38], resulting to a disruption of emotional regulation and social interaction as well as cognitive impairments evident mainly in spatial memory, modulation of vigilance and negative emotional states mediated through the hippocampus and amygdala[39], symptomatology that is present in complex PTSD even in the lack of similar biological studies to support this, at least in terms of neuromodulation alterations in complex PTSD.

Additionally, neuroimaging studies on BPD, confirm the reduction in hippocampus and amygdala volumes as well as in the temporal lobes[39-42], while a recent study of Kreiser et al[43], found that BPD patients with a comorbid lifetime history of PTSD had smaller hippocampal volumes compared to the ones that didn’t. Additionally, a study of Kuhlmann et al[44], correlated the history of trauma to BPD, showing a modification of grey matter at stress regulating centers, including the hippocampus, the amygdala, the anterior cingulate cortex and the hypothalamus.

Likewise, studies indicate that epigenetic changes upon the brain derived neurotrophic factor[45], which is a key mediator in brain plasticity, are associated to prolonged early stage trauma, contributing to the cognitive dysfunction which is often described in BPD patients[46,47].

Altogether, the similarities between studies concerning BPD and complex PTSD[17-20], in terms of the common underlying systems affected along with the clinical analogy in both disorders, both associated to prolonged stress and trauma exposure, suggest the need to re-classify subgroups of patients with BPD, especially the ones that show comorbidity with PTSD, as possible cases of complex PTSD or, as it will be discussed below, added on a spectrum of trauma-related clinical entities carrying a similar biological background with complementary clinical expression.

CONCLUSION

The new proposed diagnosis of complex PTSD in ICD-11, re-conceptualises a previous ICD-10 diagnosis namely “enduring personality change after catastrophic experience”, which carries characteristic clinical features of self-organisation dysfunction and exposure to multiple and chronic or repeated and entrapping, for the individual, traumatic events (e.g., child abuse, domestic violence, imprisonment, torture). The ICD-11 complex PTSD shares three core symptom clusters of PTSD (re-experiencing, avoidance and sense of threat), adding three additional clusters of symptoms, specifically emotional dysregulation, negative self-concept and relational disturbances. Even if a clear personality change is not required for the diagnosis of complex PTSD, the sustainable and pervasive alteration in self-organisation, especially within the group of patients who have experienced long-lasting early life complex trauma, according to the authors, suggesting that a personality change is unavoidable, essentially while even chronic PTSD alone can lead to the change of personality eventually as it has been noted in the literature[14]. Therefore, complex PTSD, often clinically resembles a subtype of BPD.

There lies the question whether complex PTSD is a clearly defined distinct entity or a PTSD comorbid with BPD. The debate focuses mainly on the fact that even if both conditions share core symptoms, such as affect dysregulation and self-organization disturbances, BPD has been traditionally described by an unstable sense of self oscillating between highly positive and highly negative self-evaluation and a relational attachment style vacillating between idealizing and denigrating perceptions of others when complex PTSD on the other hand, is defined by a deeply negative sense of self and an avoidant attachment style that are stable in nature and follow complex trauma, something that is not described in the diagnostic criteria of BPD.

However, BPD seems to be a heterogeneous diagnostic category, which can include many subtypes of patients, such as patients with bipolar disorder, depression or other personality disorders such as narcissistic personality disorder, with an accurate clinical diagnosis being difficult under practical pressures posed upon physicians and the comorbidity present among the above mentioned disorders[48]. BPD clinical features do not seem to be stable over time, and this is suggested to be influenced by the underlying biological temperament[49,50], while the comorbidity with PTSD is common but not present in all of the BPD cases[51], therefore arguing for conceptualizing some of the BPD cases belonging to a trauma spectrum disorder instead[52].

Since the etiological background for most if not all psychiatric disorders, is not linear but instead it consists of many biological, psychological and social factors, interacting between each other and continuously adjusting, shifting and variating among individuals on top of brain plasticity and ever-changing circumstances, the authors suggest that the biological correlates of disorders appearing with similar phenomenology should be better investigated.

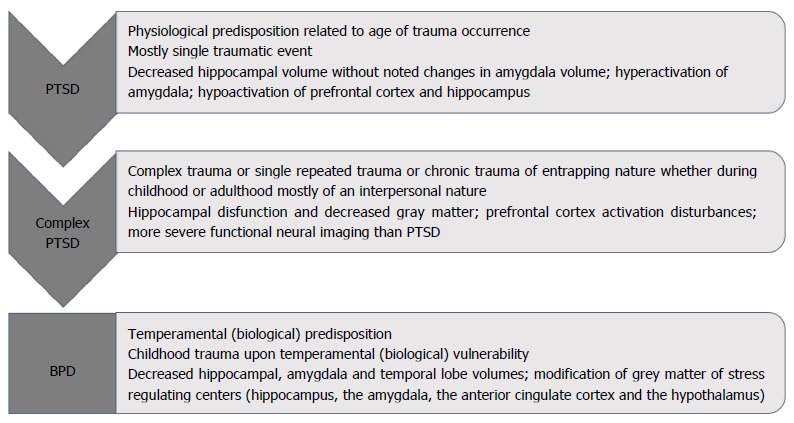

The different clinical profiles described in the most recent classification systems (Table 1) even if sharing many common clinical features, that surround PTSD, complex PTSD and BPD, are all associated with different levels of impairment and different risk factors mainly in the trauma history precipitating the phenomenology that finally occurs, which is evident in the neuroimaging findings of each disorder (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Phenomenology of posttraumatic stress disorder, complex posttraumatic stress disorder and borderline personality disorder; DSM-5 clinical features and proposed criteria of ICD-11

| DSM - 5 | ICD - 11 | |

| PTSD | Exposure to traumatic events; Intrusion symptoms; Persistent avoidance of stimuli; Negative alterations in cognitions and mood (dissociation, persistent negative beliefs of oneself, others or the world, distorted cognitions about the traumatic event, persistent negative emotional state, detachment from others, diminished interest or participation in previously enjoyed activities etc.); Alterations in arousal and reactivity; aggressive verbal and/or physical behaviour, reckless or self-destructive behaviour; depersonalisation or derealisation; Significant impairment in all areas of functioning | Exposure to an extremely threatening or horrific event or series of events; vivid intrusive memories, flashbacks, or nightmares, which are typically accompanied by strong and overwhelming emotions; avoidance of thoughts and memories, events, people, activities, situations reminiscent of the event(s); persistent perceptions of heightened current threat, hypervigilance or an enhanced startle reaction. Significant impairment in personal, family, social, educational, occupational or other important areas of functioning |

| Complex PTSD | Not included as a diagnostic entity | Exposure to an event(s) of an extremely threatening or horrific nature, most commonly prolonged or repetitive, from which escape is difficult or impossible; All diagnostic requirements for PTSD are and additionally: severe and pervasive affect dysregulation; persistent negative beliefs about oneself; deep-rooted feelings of shame, guilt or failure; persistent difficulties in sustaining relationships and in feeling close to others. Significant impairment in all areas of functioning |

| BPD | Pervasive pattern of instability of interpersonal relationships, self-image and affects and impulsivity; frantic efforts to avoid abandonment, unstable and intense interpersonal relations oscillating between idealisation and devaluation, unstable self-image or sense of self, self-harming behaviour, affective instability and marked reactivity of mood, chronic feelings of emptiness, poor anger management, transient paranoid ideation or severe dissociation | Emotionally unstable personality disorder, Borderline type: Maladaptive self and interpersonal functioning, affective instability, and maladaptive regulation strategies: Frantic efforts to avoid abandonment; unstable interpersonal relations (idealisation/devaluation); unstable self-image; impulsivity; self-damaging behaviours; marked reactivity of mood; chronic feelings of emptiness; anger management issues; dissociative symptoms |

PTSD: Posttraumatic stress disorder; BPD: Borderline personality disorder.

Figure 1.

Proposed development of the clinical phenomenology based on trauma history and biological correlates. PTSD: Posttraumatic stress disorder; BPD: Borderline personality disorder.

Since even chronic PTSD will eventually lead to personality modification, it is suggested that complex trauma exposure, even during adulthood, is a predisposing factor for complex PTSD occurring, which will, eventually, if relatively prolonged in time, lead to more severe personality changes often clinically similar to BPD. We suggest that the time of the traumatic events occurrence (i.e., early developmental stages vs adulthood), their severity and context, their duration in time and whether they are of an entrapping and interpersonal nature, posed upon a genetically predisposed background will eventually progress into enduring or permanent personality modifications. Therefore, we suggest that within the heterogeneous group of cases classified as BPD, there is a subgroup that could be possibly classified under trauma-related disorders and be therapeutically treated as such.

Concluding, the authors suggest a continuum of clinical severity and symptoms’ development in trauma-related disorders, within a spectrum of clinical features, biological background and precipitating trauma, from classic PTSD towards a subtype of BPD; especially concerning cases supposing a comorbidity with PTSD. We also suggest of complex PTSD being an “intermediate” in its phenomenological manifestation, with biological analogies seemingly supporting these hypotheses.

More studies are needed focusing on the biological background of complex PTSD and how this relates to its newly proposed clinical entity and how it correlates to the extended findings in the literature around the biology of PTSD and BPD. This is essential for examining the validity of it as a distinct and separated entity altogether or to confirm the hypothesis of a spectrum surrounding the disorders discussed above, at least within the range of cases having a history of trauma present.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors have no competing interests to disclose.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Peer-review started: November 14, 2017

First decision: December 8, 2017

Article in press: February 4, 2018

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country of origin: Greece

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A, A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Celikel FC, Liu L, Tcheremissine OV S- Editor: Wang JL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

Contributor Information

Evangelia Giourou, Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, University of Patras, Rio Patras 26500, Greece; Department of Public Health, School of Medicine, University of Patras, Rio Patras 26500, Greece.

Maria Skokou, Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, University of Patras, Rio Patras 26500, Greece.

Stuart P Andrew, Specialist Care Team Limited, Lancashire LA4 4AY, United Kingdom.

Konstantina Alexopoulou, School of Medicine, University of Patras, Rio Patras 26500, Greece.

Philippos Gourzis, Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, University of Patras, Rio Patras 26500, Greece.

Eleni Jelastopulu, Department of Public Health, School of Medicine, University of Patras, Rio Patras 26500, Greece.

References

- 1.Herman JL. Complex PTSD: A syndrome in survivors of prolonged and repeated trauma. J Trauma Stress. 1992;5:377–391. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Resick PA, Bovin MJ, Calloway AL, Dick AM, King MW, Mitchell KS, Suvak MK, Wells SY, Stirman SW, Wolf EJ. A critical evaluation of the complex PTSD literature: implications for DSM-5. J Trauma Stress. 2012;25:241–251. doi: 10.1002/jts.21699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herman J. CPTSD is a distinct entity: comment on Resick et al. (2012) J Trauma Stress. 2012;25:256–257; discussion on 260-263. doi: 10.1002/jts.21697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McLean LM, Gallop R. Implications of childhood sexual abuse for adult borderline personality disorder and complex posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:369–371. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.2.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reed GM, First MB, Elena Medina-Mora M, Gureje O, Pike KM, Saxena S. Draft diagnostic guidelines for ICD-11 mental and behavioural disorders available for review and comment. World Psychiatry. 2016;15:112–113. doi: 10.1002/wps.20322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bryant RA. The complexity of complex PTSD. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:879–881. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10040606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cloitre M, Courtois CA, Charuvastra A, Carapezza R, Stolbach BC, Green BL. Treatment of complex PTSD: results of the ISTSS expert clinician survey on best practices. J Trauma Stress. 2011;24:615–627. doi: 10.1002/jts.20697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDonnell M, Robjant K, Katona C. Complex posttraumatic stress disorder and survivors of human rights violations. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2013;26:1–6. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32835aea9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Courtois CA. Complex trauma, complex reactions: Assessment and treatment. Psychol Trauma. 2008;S:86–100. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palic S, Zerach G, Shevlin M, Zeligman Z, Elklit A, Solomon Z. Evidence of complex posttraumatic stress disorder (CPTSD) across populations with prolonged trauma of varying interpersonal intensity and ages of exposure. Psychiatry Res. 2016;246:692–699. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.10.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Dijke A, Ford JD, Frank LE, van der Hart O. Association of Childhood Complex Trauma and Dissociation With Complex Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms in Adulthood. J Trauma Dissociation. 2015;16:428–441. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2015.1016253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cloitre M, Stolbach BC, Herman JL, van der Kolk B, Pynoos R, Wang J, Petkova E. A developmental approach to complex PTSD: childhood and adult cumulative trauma as predictors of symptom complexity. J Trauma Stress. 2009;22:399–408. doi: 10.1002/jts.20444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cloitre M, Petkova E, Wang J, Lu Lassell F. An examination of the influence of a sequential treatment on the course and impact of dissociation among women with PTSD related to childhood abuse. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29:709–717. doi: 10.1002/da.21920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ehlers A, Maercker A, Boos A. Posttraumatic stress disorder following political imprisonment: the role of mental defeat, alienation, and perceived permanent change. J Abnorm Psychol. 2000;109:45–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Regier DA, Kuhl EA, Kupfer DJ. The DSM-5: Classification and criteria changes. World Psychiatry. 2013;12:92–98. doi: 10.1002/wps.20050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cloitre M, Garvert DW, Brewin CR, Bryant RA, Maercker A. Evidence for proposed ICD-11 PTSD and complex PTSD: a latent profile analysis. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2013;4 doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v4i0.20706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marinova Z, Maercker A. Biological correlates of complex posttraumatic stress disorder-state of research and future directions. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2015;6:25913. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v6.25913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomaes K, Dorrepaal E, Draijer NP, de Ruiter MB, Elzinga BM, van Balkom AJ, Smoor PL, Smit J, Veltman DJ. Increased activation of the left hippocampus region in Complex PTSD during encoding and recognition of emotional words: a pilot study. Psychiatry Res. 2009;171:44–53. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomaes K, Dorrepaal E, Draijer N, de Ruiter MB, Elzinga BM, Sjoerds Z, van Balkom AJ, Smit JH, Veltman DJ. Increased anterior cingulate cortex and hippocampus activation in Complex PTSD during encoding of negative words. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2013;8:190–200. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsr084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomaes K, Dorrepaal E, Draijer N, de Ruiter MB, Elzinga BM, van Balkom AJ, Smit JH, Veltman DJ. Treatment effects on insular and anterior cingulate cortex activation during classic and emotional Stroop interference in child abuse-related complex post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychol Med. 2012;42:2337–2349. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712000499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomaes K, Dorrepaal E, van Balkom AJ, Veltman DJ, Smit JH, Hoogendoorn AW, Draijer N. [Complex PTSD following early-childhood trauma: emotion-regulation training as addition to the PTSD guideline] Tijdschr Psychiatr. 2015;57:171–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karatzias T, Shevlin M, Fyvie C, Hyland P, Efthymiadou E, Wilson D, Roberts N, Bisson JI, Brewin CR, Cloitre M. Evidence of distinct profiles of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and Complex Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (CPTSD) based on the new ICD-11 Trauma Questionnaire (ICD-TQ) J Affect Disord. 2017;207:181–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perkonigg A, Höfler M, Cloitre M, Wittchen HU, Trautmann S, Maercker A. Evidence for two different ICD-11 posttraumatic stress disorders in a community sample of adolescents and young adults. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2016;266:317–328. doi: 10.1007/s00406-015-0639-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ford JD, Courtois CA. Complex PTSD, affect dysregulation, and borderline personality disorder. Borderline Personal Disord Emot Dysregul. 2014;1:9. doi: 10.1186/2051-6673-1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Battle DE. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) Codas. 2013;25:191–192. doi: 10.1590/s2317-17822013000200017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Powers A, Fani N, Carter S, Cross D, Cloitre M, Bradley B. Differential predictors of DSM-5 PTSD and ICD-11 complex PTSD among African American women. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2017;8:1338914. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2017.1338914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Dijke A, Ford JD, van der Hart O, van Son M, van der Heijden P, Bühring M. Affect dysregulation in borderline personality disorder and somatoform disorder: differentiating under- and over-regulation. J Pers Disord. 2010;24:296–311. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2010.24.3.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Battle CL, Shea MT, Johnson DM, Yen S, Zlotnick C, Zanarini MC, Sanislow CA, Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, Grilo CM, et al. Childhood maltreatment associated with adult personality disorders: findings from the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study. J Pers Disord. 2004;18:193–211. doi: 10.1521/pedi.18.2.193.32777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yen S, Shea MT, Battle CL, Johnson DM, Zlotnick C, Dolan-Sewell R, Skodol AE, Grilo CM, Gunderson JG, Sanislow CA, et al. Traumatic exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder in borderline, schizotypal, avoidant, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders: findings from the collaborative longitudinal personality disorders study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2002;190:510–518. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200208000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J, Reich DB, Silk KR. Prediction of the 10-year course of borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:827–832. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.5.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cloitre M, Garvert DW, Weiss B, Carlson EB, Bryant RA. Distinguishing PTSD, Complex PTSD, and Borderline Personality Disorder: A latent class analysis. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2014;5 doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v5.25097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leichsenring F, Leibing E, Kruse J, New AS, Leweke F. Borderline personality disorder. Lancet. 2011;377:74–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61422-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Winsper C, Lereya ST, Marwaha S, Thompson A, Eyden J, Singh SP. The aetiological and psychopathological validity of borderline personality disorder in youth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016;44:13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mehta D, Binder EB. Gene × environment vulnerability factors for PTSD: the HPA-axis. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62:654–662. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Southwick SM, Axelrod SR, Wang S, Yehuda R, Morgan CA 3rd, Charney D, Rosenheck R, Mason JW. Twenty-four-hour urine cortisol in combat veterans with PTSD and comorbid borderline personality disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2003;191:261–262. doi: 10.1097/01.NMD.0000061140.93952.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wingenfeld K, Driessen M, Adam B, Hill A. Overnight urinary cortisol release in women with borderline personality disorder depends on comorbid PTSD and depressive psychopathology. Eur Psychiatry. 2007;22:309–312. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Friedel RO. Dopamine dysfunction in borderline personality disorder: a hypothesis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:1029–1039. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grosjean B, Tsai GE. NMDA neurotransmission as a critical mediator of borderline personality disorder. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2007;32:103–115. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Driessen M, Herrmann J, Stahl K, Zwaan M, Meier S, Hill A, Osterheider M, Petersen D. Magnetic resonance imaging volumes of the hippocampus and the amygdala in women with borderline personality disorder and early traumatization. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:1115–1122. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.12.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Irle E, Lange C, Sachsse U. Reduced size and abnormal asymmetry of parietal cortex in women with borderline personality disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:173–182. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tebartz van Elst L, Hesslinger B, Thiel T, Geiger E, Haegele K, Lemieux L, Lieb K, Bohus M, Hennig J, Ebert D. Frontolimbic brain abnormalities in patients with borderline personality disorder: a volumetric magnetic resonance imaging study. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:163–171. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01743-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rossi R, Lanfredi M, Pievani M, Boccardi M, Beneduce R, Rillosi L, Giannakopoulos P, Thompson PM, Rossi G, Frisoni GB. Volumetric and topographic differences in hippocampal subdivisions in borderline personality and bipolar disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2012;203:132–138. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kreisel SH, Labudda K, Kurlandchikov O, Beblo T, Mertens M, Thomas C, Rullkötter N, Wingenfeld K, Mensebach C, Woermann FG, et al. Volume of hippocampal substructures in borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2015;231:218–226. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2014.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kuhlmann A, Bertsch K, Schmidinger I, Thomann PA, Herpertz SC. Morphometric differences in central stress-regulating structures between women with and without borderline personality disorder. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2013;38:129–137. doi: 10.1503/jpn.120039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Duman RS, Monteggia LM. A neurotrophic model for stress-related mood disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:1116–1127. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Perroud N, Salzmann A, Prada P, Nicastro R, Hoeppli ME, Furrer S, Ardu S, Krejci I, Karege F, Malafosse A. Response to psychotherapy in borderline personality disorder and methylation status of the BDNF gene. Transl Psychiatry. 2013;3:e207. doi: 10.1038/tp.2012.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thaler L, Gauvin L, Joober R, Groleau P, de Guzman R, Ambalavanan A, Israel M, Wilson S, Steiger H. Methylation of BDNF in women with bulimic eating syndromes: associations with childhood abuse and borderline personality disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2014;54:43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2014.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kernberg OF, Yeomans FE. Borderline personality disorder, bipolar disorder, depression, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and narcissistic personality disorder: Practical differential diagnosis. Bull Menninger Clin. 2013;77:1–22. doi: 10.1521/bumc.2013.77.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Reich DB, Silk KR, Hudson JI, McSweeney LB. The subsyndromal phenomenology of borderline personality disorder: a 10-year follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:929–935. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hopwood CJ, Newman DA, Donnellan MB, Markowitz JC, Grilo CM, Sanislow CA, Ansell EB, McGlashan TH, Skodol AE, Shea MT, et al. The stability of personality traits in individuals with borderline personality disorder. J Abnorm Psychol. 2009;118:806–815. doi: 10.1037/a0016954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grant BF, Chou SP, Goldstein RB, Huang B, Stinson FS, Saha TD, Smith SM, Dawson DA, Pulay AJ, Pickering RP, et al. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder: results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:533–545. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lewis KL, Grenyer BF. Borderline personality or complex posttraumatic stress disorder? An update on the controversy. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2009;17:322–328. doi: 10.3109/10673220903271848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]