Highlights

-

•

No difference in pseudoprogression rate six months after proton or photon therapy.

-

•

Oligodendrogliomas develop pseudoprogression sooner after protons vs. photons.

-

•

Astrocytomas develop pseudoprogression at similar time after protons vs. photons.

Keywords: Radiation, Proton, Oligodendroglioma, Astrocytoma, Pseudoprogression, Glioma

Abstract

Background and purpose

Proton therapy is increasingly used to treat primary brain tumors. There is concern for higher rates of pseudoprogression (PsP) after protons compared to photons. The purposes of this study are to compare the rate of PsP after proton vs. photon therapy for grade II and III gliomas and to identify factors associated with the development of PsP.

Materials and methods

Ninety-nine patients age >18 years with grade II or III glioma treated with photons or protons were retrospectively reviewed. Demographic data, IDH and 1p19q status, and treatment factors were analyzed for association with PsP, progression free survival (PFS), and overall survival (OS).

Results

Sixty-five patients were treated with photons and 34 with protons. Among those with oligodendroglioma, PsP developed in 6/42 photon-treated patients (14.3%) and 4/25 proton-treated patients (16%, p = 1.00). Among those with astrocytoma, PsP developed in 3/23 photon-treated patients (13%) and 1/9 proton-treated patients (11.1%, p = 1.00). There was no difference in PsP rate based on radiation type, radiation dose, tumor grade, 1p19q codeletion, or IDH status. PsP occurred earlier in oligodendroglioma patients treated with protons compared to photons, 48 days vs. 131 days, p < .01. On multivariate analyses, gross total resection (p = .03, HR = 0.48, 95%CI = 0.25–0.93) and PsP (p = .04, HR = 0.22, 95% CI = 0.05–0.91) were associated with better PFS; IDH mutation was associated with better OS (p < .01, HR = 0.22, 95%CI = 0.08–0.65).

Conclusions

Patients with oligodendroglioma but not astrocytoma develop PsP earlier after protons compared to photons. PsP was associated with better PFS.

Introduction

Roughly one-third of gliomas are grade II or III oligodendrogliomas or astrocytomas and the treatment of these tumors remain controversial [1]. Maximally safe resection as well as chemotherapy play important roles. Radiation therapy is also known to contribute to improved disease control; however, concerns regarding adverse effects of radiation therapy remain. Photon therapy is the most commonly used radiation modality to treat gliomas, but proton therapy is increasingly considered due to its potential to decrease radiation dose to normal tissues [2]. In a prospective trial, investigators found that proton therapy was well tolerated with no evidence for cognitive decline or decrease in quality of life [3].

Pseudoprogression (PsP) is the development of transient contrast enhancing changes within six months after radiation which can mimic tumor progression [4]. PsP is thought to be the result of radiation-induced alteration of brain vasculature through injury to oligodendrocytes, ultimately weakening the blood brain barrier and increasing contrast enhancement [5], [6], [7]. Rates of PsP range from 5% to 31% in small cohort studies [8]. Patients with PsP can be symptomatic, which can be clinically concerning [7]. Difficulties in distinguishing between true tumor progression and PsP introduce uncertainty into clinical decision making. This often leads to more frequent MRIs, unnecessary biopsies, alterations in ongoing therapy, elevated costs, and increasing risk of complications. Imaging techniques have been proposed to distinguish true progression from PsP [7], [9], [10], but none are in routine clinical use. Complicating the picture, as proton therapy becomes more available and increasingly used in the treatment of these tumors, there is emerging concern that PsP may occur more frequently following proton therapy [11], [12], suggesting a different biological interaction of proton beams with gliomas compared to that of photon therapy.

PsP has been well described for glioblastoma, but there are limited data on the development of PsP in grade II and III gliomas [13], [14]. To investigate the factors associated with the development of PsP in glioma after radiation therapy, including both protons and photons, we retrospectively reviewed outcomes of grade II and grade III glioma patients treated with radiation therapy.

Materials and methods

Patient data collection

All work was performed on an Institutional Review Board approved protocol at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. The study population included patients at least 18 years old with histologically confirmed grade II or III oligodendroglioma or astrocytoma per the 2007 WHO criteria [15] treated with proton or photon therapy between 2004 and 2015. All patients had serial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) available for at least 6 months following completion of radiation therapy. Demographic and clinical characteristics were compiled from review of the medical records. Tumor histology, grade, 1p19q status, and IDH mutation status (IDH1 and IDH2) were obtained from the pathology report. Extent of surgical resection was based on review of the imaging and the neurosurgeon’s operative note.

Radiation technique

All patients were treated with intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) or proton therapy. Gross tumor volume (GTV) was defined as the surgical cavity and any residual contrast enhancing or non-contrast enhancing tumor. The clinical target volume (CTV) was defined as an anatomically-constrained 1–1.5 cm expansion on the GTV to identify volumes at risk for microscopic extension, with expansions based on the preference of the treating physician. Dose was prescribed to the planning tumor volume (PTV) for patients treated with IMRT, which was delivered with 6MV photons. For patients treated with proton therapy, distal beam margins were determined individually for each beam as previously described [16]. Proton therapy was delivered with either passive scatter (n = 29) or scanning beam technique (n = 5). For proton therapy, a relative biological effectiveness (RBE) of 1.1 was used per ICRU 78 [17]. Radiation treatment records were reviewed to obtain volume data for GTV and CTV.

Imaging review

MR images were evaluated for PsP by a neuroradiologist blinded to treatment information. PsP was defined as new areas of contrast enhancement that developed within 6 months of completion of radiotherapy and were concerning for possible tumor progression [4]. These areas of enhancement either resolved or remained stable over time without clinical intervention. True progression was defined as areas of enhancement that continued to grow and required further tumor specific therapy. Other diagnostic considerations included reactive changes and infarct. Reactive post-operative enhancement is typically noted 45–72 h following surgery; although this can be confounding at times, reactive enhancement is usually benign in appearance, marginal and/or dural. To avoid misinterpretation of post-operative ischemic enhancement, diffusion weighted images were analyzed and affected areas were excluded from assessment.

Time to PsP was calculated as the interval from the last day of radiation to the first MRI showing changes consistent with PsP.

Statistical analysis

All statistical calculations were performed with Stata/MP 14.2 software. Rates of PsP and other clinical variables were descriptively summarized and compared using Fisher exact test and Wilcoxon rank-sum (Mann-Whitney) as appropriate. Statistics were reported for comparison as grouped variables and continuous variables when applicable. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to identify correlations between clinical variables and PsP, overall survival (OS), and progression free survival (PFS) using Cox regression analysis. Variables included in univariate and multivariate analyses were age, gender, histology, tumor grade, tumor location, radiation dose, radiation type, extent of surgical resection, concurrent and adjuvant chemotherapy regimen, treatment volumes, 1p/19q codeletion status, and IDH mutation status. PFS and OS were measured from the date of diagnosis and calculated with Kaplan-Meier estimates [18]. Rates between groups were compared using log-rank tests. Significance was set at p < .05, and all statistical tests were 2 sided.

Results

A total of 99 patients were identified, 65 treated with photons and 34 with protons. Sixty-seven patients were treated for oligodendroglioma and 32 for astrocytoma/glioma NOS. Median radiographic follow-up after radiation therapy was 46 and 38 months in the oligodendroglioma photon and proton groups respectively, and 46 and 24 months in the astrocytoma photon and proton groups respectively.

Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Patients with grade III tumors were more likely to be treated with photon therapy and to receive concurrent chemotherapy than patients with grade II tumors. All other clinical variables were evenly distributed across the groups.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with oligodendroglioma or astrocytoma treated with protons versus photons.

| All (n = 99) | Photon |

Proton |

p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oligo (n = 42) | Astro (n = 23) | Oligo (n = 25) | Astro (n = 9) | |||

| Age (y) | ||||||

| Median | 48 | 51.5 | 47 | 47 | 46 | 0.15 |

| Range | 24–94 | 34–94 | 24–67 | 24–71 | 26–53 | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 35 | 15 | 8 | 9 | 3 | 1.00 |

| Male | 64 | 27 | 15 | 16 | 6 | |

| Pseudoprogression | ||||||

| Yes | 14 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1.00 |

| No | 85 | 36 | 20 | 21 | 8 | |

| Tumor location | ||||||

| Frontal lobe | 58 | 28 | 12 | 16 | 2 | 0.09 |

| Other | 41 | 14 | 11 | 9 | 7 | |

| Grade | ||||||

| II | 36 | 12 | 6 | 11 | 7 | 0.03 |

| III | 63 | 30 | 17 | 14 | 2 | |

| Surgery | ||||||

| STR | 65 | 29 | 14 | 16 | 6 | 0.95 |

| GTR | 34 | 13 | 9 | 9 | 3 | |

| Concurrent chemotherapy | ||||||

| Yes | 14 | 3 | 10 | 0 | 1 | <0.01 |

| No | 85 | 39 | 13 | 25 | 8 | |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | ||||||

| Yes | 54 | 21 | 15 | 16 | 2 | 0.11 |

| No | 45 | 21 | 8 | 9 | 7 | |

| Total dose (GyRBE) | ||||||

| Median | 57 | 57 | 57 | 54 | 50.4 | 0.34 |

| Range | 40–60 | 50–57 | 50–60 | 40–57 | 50.4–57 | |

| 1p19q codeletion | ||||||

| Yes | 47 | 26 | 3 | 18 | 0 | <0.01 |

| No | 27 | 6 | 10 | 6 | 5 | |

| Unknown | 25 | 10 | 10 | 1 | 4 | |

| IDH mutation | ||||||

| Yes | 52 | 15 | 15 | 16 | 6 | 0.33 |

| No | 18 | 5 | 8 | 2 | 3 | |

| Unknown | 29 | 22 | 0 | 7 | 0 | |

| CTV/GTV | ||||||

| Median | 3.1 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.2 | 3.8 | 0.47 |

| Range | 0.6–41.2 | 0.6–41.2 | 1.8–7.1 | 1.7–9.0 | 1.7–7.6 | |

Oligo, oligodendroglioma; Astro, astrocytoma/glioma NOS; CTV, clinical target volume; GTV, gross tumor volume.

Pseudoprogression

Rates of PsP were not different based on tumor type or radiation modality (Table 1). PsP (Fig. 1) occurred in 10/67 patients with oligodendroglioma (14.9%) and 4/32 patients with astrocytoma (12.5%, p = 1.00). For patients with oligodendroglioma, PsP developed in 6/42 photon-treated patients (14.3%) and 4/25 proton-treated patients (16%, p = 1.00). For patients with astrocytoma, PsP developed in 3/23 photon-treated patients (13%) and 1/9 proton-treated patients (11.1%, p = 1.00). Of 65 patients treated with photons, 9 developed PsP (13.8%) vs. 5 of 34 patients (14.7%) treated with protons (p = 1.00).

Fig. 1.

A 41 year old man with a grade II astrocytoma in the right temporal lobe treated with proton therapy to 54 GyRBE, 3.5 months after subtotal resection. (A) Post-contrast axial T1 weighted image demonstrates a right temporal lobe resection cavity with linear enhancement along the posterior margin. (B) One month after radiation, imaging reveals nodular enhancement along the medial aspect of the resection margin. (C) The enhancement resolved without any additional therapy on follow-up MRI one year after proton therapy.

Univariate analysis was performed to identify factors associated with PsP. Radiation modality, histology, grade, 1p19q status, IDH status, the use of chemotherapy, the extent of surgical resection, and radiation dose were not correlated with PsP. Of note, 25 patients were not tested for 1p19q codeletion and 29 patients were not tested for IDH status.

Characteristics of patients with PsP are shown in Table 2. In patients with oligodendroglioma treated with proton therapy, the time to PsP was shorter (48 days vs. 131 days in patients treated with photons, p < .01). There was no difference in time to PsP in patients with astrocytoma treated with photons versus protons (Table 2). Three of the 14 patients with PsP were symptomatic with headaches (n = 2) and an increase in seizure frequency (n = 1). No patients required steroids or Avastin.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of glioma patients with pseudoprogression treated with photon therapy versus proton therapy.

| WHO grade Histology | 1p/19q codel | IDH1 mutation | Resection/No. of surgeries | Prior chemo | Dose GyRBE | Fractions | Conc chemo | Adj chemo | Time to PsP (days) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Photon | |||||||||||

| 1 | III | Oligo | Yes | No | STR/2 | No | 57 | 30 | No | TMZ | 158 |

| 2 | III | Oligo | Unk | Unk | STR/1 | No | 57 | 30 | No | TMZ | 70 |

| 3 | III | Oligo | Yes | No | STR/2 | No | 57 | 30 | No | TMZ | 131 |

| 4 | III | Oligo | Unk | Unk | STR/1 | No | 57 | 30 | No | TMZ | 151 |

| 5 | III | Oligo | Yes | Yes | GTR/2 | TMZ | 57 | 30 | No | No | 132 |

| 6 | II | Oligo | Unk | Unk | GTR/2 | No | 50.4 | 28 | No | No | 116 |

| 7 | III | Astro | No | No | GTR/3 | No | 57 | 30 | TMZ | TMZ | 18 |

| 8 | II | Astro | No | Yes | STR/1 | No | 50 | 25 | No | TMZ | 34 |

| 9 | II | Astro | No | Yes | STR/1 | No | 50.4 | 28 | No | No | 31 |

| Proton | |||||||||||

| 1 | III | Oligo | Yes | Yes | STR/1 | No | 57 | 30 | No | PCV | 77 |

| 2 | III | Oligo | Yes | Yes | STR/2 | No | 57 | 30 | No | PCV | 20 |

| 3 | II | Oligo | No | Unk | STR/1 | No | 50.4 | 28 | No | No | 18 |

| 4 | II | Oligo | Yes | Yes | STR/1 | No | 50.4 | 28 | No | No | 76 |

| 5 | II | Astro | No | Yes | STR/1 | No | 54 | 30 | No | No | 32 |

Oligo, oligodendroglioma; Astro, astrocytoma/glioma NOS; Unk, unknown; Prior chemo, chemotherapy prior to radiation; Conc chemo, concurrent chemotherapy; Adj chemo, adjuvant chemotherapy; STR, subtotal resection; GTR, gross total resection; TMZ, temozolomide; PCV, Procarbazine, CCNU, and Vincristine; CCNU, Lomustine; GyRBE, Gray-relative biological effect; Time to PsP (days), time to pseudoprogression after radiation therapy in days; Codel, codeletion.

Survival

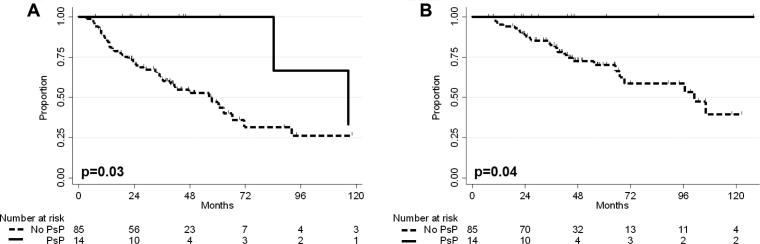

The median follow up of patients with PsP treated with photons was 45 months and 22 months for patients with PsP treated with protons (p = .04). PFS and OS were significantly improved in patients with PsP (Fig. 2). PFS at 3 years was 100% for patients with PsP and 61.6% in patients without PsP (p = .03). Median time to progression was also shorter in patients that did not have PsP, 21 months vs. 100 months, p = .02. OS at 3 years was 100% for patients with PsP and 82.6% in patients without PsP (p = .04).

Fig. 2.

(A) PFS for patients with PsP vs. patients without PsP. PFS at 3 years was 100% in patients with PsP and 61.6% in patients without PsP (p = .03). (B) OS for patients with PsP vs. patients without PsP. OS at 3 years was 100% in patients with PsP and 82.6% in patients without PsP (p = .04).

On univariate analysis, PsP (p = .04, HR = 0.23, CI = 0.05–0.94), gross total resection (p = .05, HR = 0.52, 95%CI = 0.27–1.00), and IDH mutation (p = .02, HR = 0.36, 95%CI = 0.16–0.84) were all associated with improved PFS. On multivariate analysis, GTR (p = .03, HR = 0.48, 95%CI = 0.25–0.93) and PsP (p = .04, HR = 0.22, 95%CI = 0.05–0.91) correlated with improved PFS. IDH mutation was the only variable associated with better OS on univariate (p < .01, HR = 0.22, 95%CI = 0.08–0.65) and multivariate analysis (p < .01, HR = 0.22, 95%CI = 0.08–0.65).

Discussion

This is the largest study of grade II and III glioma patients treated with proton versus photon radiation. For the whole study population, rates of PsP did not differ based on radiation type, radiation dose, 1p19q codeletion, tumor histology, or tumor grade. For the subset of patients with oligodendroglioma, those treated with proton therapy developed PsP sooner compared to those treated with photon radiation. This difference was not observed in patients with astrocytoma. Although the patient numbers are small, this observation suggests a differential biological effect of proton radiation in oligodendroglioma that is not present in astrocytoma.

It has previously been reported that gliomas with 1p19q codeletion treated with photon radiation therapy have a lower risk of developing PsP [14], [19]. In our study, there was no difference in the rate of development of PsP based on 1p19q codeletion or IDH status.

It has been suggested that the occurrence of PsP may be linked to more aggressive treatment. A prospective study in glioblastoma has shown over a three-fold increase in rates of PsP with the use of adjuvant temozolomide in addition to radiation in patients with methylated MGMT promoters [20]. Our data did not show an association between the rate of PsP and the use of more aggressive therapy including adjuvant chemotherapy, gross total resection, or increased radiation dose for grade II and III gliomas.

IDH status was associated with improved OS on multivariate analysis, as expected [21], [22]. The association between IDH mutation status and PsP is less clear. IDH1 mutation has been shown to increase the risk of PsP in glioblastoma [23] and decrease the risk of PsP in grade II and III gliomas [19]. In our study, we found no relationship between the occurrence of PsP and IDH status.

We found a significant improvement in PFS for patients with PsP that was upheld on univariate and multivariate analyses. Although PsP was significant on Kaplan-Meier survival analysis for OS, it was not significant in univariate analysis of OS. The median follow-up of proton and photon patient that developed PsP in our study was 22 months and 45 months, respectively. Given that 5-year survival for patients with grade II and III glioma is 50–80% [1], a clearer OS advantage for PsP in grade II and III gliomas may emerge with longer follow-up. PsP has been associated with improved OS in glioblastoma [20], [24].

This is the first study comparing the rates of PsP after photon and proton radiation in grade II and III glioma. All patients were treated contemporaneously at a single institution. Because of this study’s retrospective nature, imbalances in tumor grade and molecular profiles as well as the use of concurrent chemotherapy along with radiation modalities reflect differences in practice patterns over the time of the study. Another limitation of this study is that tumor classification and clinical treatment decisions were made according to the WHO 2007 classification that relied on tumor histology [15]; 1p19q codeletion and IDH1 mutation status were not always determined. In our study population, immunohistochemistry for the R132H mutation in IDH1 was the primary method to determine IDH1 mutation status; this would not capture non-canonical IDH1 or IDH2 mutations [25]. Recent studies have supported genetic and molecular classification instead of histologic grade to determine tumor classification and patient prognosis [26], [27], [28]. Genomic analysis of long term glioma survivors has shown that they are more likely to harbor a mutation in the IDH1 or IDH2 genes [29]. Likewise, a subset of gliomas with codeletion of 1p19q have been found to be more sensitive to combination chemoradiotherapy with an associated significant increase in survival [30]. Because of these observations, 1p19q codeletion and IDH mutation status are included in the 2016 WHO classification of brain tumors [15].

Conclusion

Overall rates of PsP were similar in patients treated with photons versus protons. Patients with oligodendroglioma who developed PsP did so at a shorter interval after proton therapy than photon therapy. These differences were not observed in astrocytoma, suggesting a differential biological effect of proton therapy in oligodendroglioma. Patients with PsP had improved PFS, suggesting a role for PsP as a predictive marker after radiation therapy.

Footnotes

This work was previously presented at the Society for Neuro-Oncology 2016 Annual Meeting in Scottsdale, Arizona.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctro.2018.01.002.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Ostrom Q.T., Gittleman H., Liao P., Rouse C., Chen Y., Dowling J. CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2007–2011. Neuro-oncology. 2014;16(Suppl. 4):iv1–iv63. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nou223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dennis E.R., Bussiere M.R., Niemierko A., Lu M.W., Fullerton B.C., Loeffler J.S. A comparison of critical structure dose and toxicity risks in patients with low grade gliomas treated with IMRT versus proton radiation therapy. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2013;12:1–9. doi: 10.7785/tcrt.2012.500276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shih H.A., Sherman J.C., Nachtigall L.B., Colvin M.K., Fullerton B.C., Daartz J. Proton therapy for low-grade gliomas: results from a prospective trial. Cancer. 2015;121:1712–1719. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brandsma D., Stalpers L., Taal W., Sminia P., van den Bent M.J. Clinical features, mechanisms, and management of pseudoprogression in malignant gliomas. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:453–461. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70125-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rider W.D. Radiation damage to the brain–a new syndrome. J Can Assoc Radiol. 1963;14:67–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson C.B., Crafts D., Levin V. Brain tumors: criteria of response and definition of recurrence. Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1977;46:197–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parvez K., Parvez A., Zadeh G. The diagnosis and treatment of pseudoprogression, radiation necrosis and brain tumor recurrence. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:11832–11846. doi: 10.3390/ijms150711832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hygino da Cruz LC L.C., Jr., Rodriguez I., Domingues R.C., Gasparetto E.L., Sorensen A.G. Pseudoprogression and pseudoresponse: imaging challenges in the assessment of posttreatment glioma. Am J Neuroradiol. 2011;32:1978–1985. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ma B., Blakeley J.O., Hong X., Zhang H., Jiang S., Blair L. Applying amide proton transfer-weighted MRI to distinguish pseudoprogression from true progression in malignant gliomas. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2016;44:456–462. doi: 10.1002/jmri.25159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meyzer C., Dhermain F., Ducreux D., Habrand J.L., Varlet P., Sainte-Rose C. A case report of pseudoprogression followed by complete remission after proton-beam irradiation for a low-grade glioma in a teenager: the value of dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI. Radiat Oncol. 2010;5:9. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-5-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGovern S.L., Okcu M.F., Munsell M.F., Kumbalasseriyil N., Grosshans D.R., McAleer M.F. Outcomes and acute toxicities of proton therapy for pediatric atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor of the central nervous system. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;90:1143–1152. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.08.354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gunther J.R., Sato M., Chintagumpala M., Ketonen L., Jones J.Y., Allen P.K. Imaging changes in pediatric intracranial ependymoma patients treated with proton beam radiation therapy compared to intensity modulated radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;93:54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ellingson B.M., Wen P.Y., van den Bent M.J., Cloughesy T.F. Pros and cons of current brain tumor imaging. Neuro-oncology. 2014;16(Suppl. 7):vii2–vii11. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nou224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin A.L., Liu J., Evans J., Leuthardt E.C., Rich K.M., Dacey R.G. Codeletions at 1p and 19q predict a lower risk of pseudoprogression in oligodendrogliomas and mixed oligoastrocytomas. Neuro-oncology. 2014;16:123–130. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/not142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Louis D.N., Ohgaki H., Wiestler O.D., Cavenee W.K., Burger P.C., Jouvet A. The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:97–109. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0243-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grosshans D.R., Mohan R., Gondi V., Shih H.A., Mahajan A., Brown P.D. The role of image-guided intensity modulated proton therapy in glioma. Neuro-oncology. 2017;19:ii30–ii37. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nox002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements report No. 78, J ICRU 2007;7(2), Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007.

- 18.Kaplan E.L., Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin A.L., White M., Miller-Thomas M.M., Fulton R.S., Tsien C.I., Rich K.M. Molecular and histologic characteristics of pseudoprogression in diffuse gliomas. J Neurooncol. 2016;130:529–533. doi: 10.1007/s11060-016-2247-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brandes A.A., Franceschi E., Tosoni A., Blatt V., Pession A., Tallini G. MGMT promoter methylation status can predict the incidence and outcome of pseudoprogression after concomitant radiochemotherapy in newly diagnosed glioblastoma patients. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2192–2197. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parsons D.W., Jones S., Zhang X., Lin J.C., Leary R.J., Angenendt P. An integrated genomic analysis of human glioblastoma multiforme. Science. 2008;321:1807–1812. doi: 10.1126/science.1164382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sonoda Y., Kumabe T., Nakamura T., Saito R., Kanamori M., Yamashita Y. Analysis of IDH1 and IDH2 mutations in Japanese glioma patients. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:1996–1998. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01270.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Motegi H., Kamoshima Y., Terasaka S., Kobayashi H., Yamaguchi S., Tanino M. IDH1 mutation as a potential novel biomarker for distinguishing pseudoprogression from true progression in patients with glioblastoma treated with temozolomide and radiotherapy. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2013;30:67–72. doi: 10.1007/s10014-012-0109-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gahramanov S., Varallyay C., Tyson R.M., Lacy C., Fu R., Netto J.P. Diagnosis of pseudoprogression using MRI perfusion in patients with glioblastoma multiforme may predict improved survival. CNS Oncol. 2014;3:389–400. doi: 10.2217/cns.14.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Louis D.N., Perry A., Reifenberger G., von Deimling A., Figarella-Branger D., Cavenee W.K. The 2016 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131:803–820. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1545-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olar A., Wani K.M., Alfaro-Munoz K.D., Heathcock L.E., van Thuijl H.F., Gilbert M.R. IDH mutation status and role of WHO grade and mitotic index in overall survival in grade II-III diffuse gliomas. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;129:585–596. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1398-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reuss D.E., Mamatjan Y., Schrimpf D., Capper D., Hovestadt V., Kratz A. IDH mutant diffuse and anaplastic astrocytomas have similar age at presentation and little difference in survival: a grading problem for WHO. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;129:867–873. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1438-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suzuki H., Aoki K., Chiba K., Sato Y., Shiozawa Y., Shiraishi Y. Mutational landscape and clonal architecture in grade II and III gliomas. Nat Genet. 2015;47:458–468. doi: 10.1038/ng.3273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holdhoff M., Cairncross G.J., Kollmeyer T.M., Zhang M., Zhang P., Mehta M.P. Genetic landscape of extreme responders with anaplastic oligodendroglioma. Oncotarget. 2017;8:35523–35531. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cairncross G., Wang M., Shaw E., Jenkins R., Brachman D., Buckner J. Phase III trial of chemoradiotherapy for anaplastic oligodendroglioma: long-term results of RTOG 9402. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:337–343. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.2674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.