Abstract

Objectives

To investigate diffusion of moxifloxacin through bandage contact lenses (BCLs) versus corneal collagen shields (CSs), the relative ability of BCLs and CSs to release moxifloxacin, and the potential of release of moxifloxacin from CSs in the clinical setting.

Methods

Using an in vitro model, the diffusion of 5% moxifloxacin across BCLs and CSs were compared. Next, the amount of drug release from BCLs and CSs soaked in 0.5% moxifloxacin were measured. Finally, based on a clinical model, CSs were soaked in Vigamox (commercial moxifloxacin) and the total concentration released was detected. CSs remained intact after 24 hours; therefore, enzymatic digestion and mechanical grinding of the CS was performed to determine whether further drug could be released. The concentration of moxifloxacin was measured using a spectrophotometer at set time points up to 24 hours.

Results

In the diffusion assay, 35.7 ± 10.5% diffused through the BCLs and 36.2 ± 11.8% diffused through the CSs (P=0.77). The absorption assay demonstrated at 120 min, a total of 33.3 ± 6.77μg/ml was released from BCLs compared to 45.8 ± 5.2 μg/ml from the CSs (p= 0.0008). In vitro experiments to simulate clinical application of Vigamox-soaked CS found the concentration of moxifloxacin released of 127.7 ± 7.25 μg/ml in 2mL PBS over 24 hours.

Conclusions

Moxifloxacin diffuses through BCL and CS at similar rates; however, CS has greater capacity to absorb and release moxifloxacin compared to BCL. Vigamox-soaked CSs released 250 μg of moxifloxacin, and may be a useful method to prevent endophthalmitis.

Keywords: Collagen shield, bandage contact lens, antibiotic, moxifloxacin, cornea

Introduction

In current clinical practice, there are many uses for silicone-hydrogel (SH) contact lenses for ocular therapy. Soft bandage contact lenses (BCLs) are used to protect injured corneas from further damage, encourage healing, and deliver certain drugs to the eye to prevent infection such as keratitis.1 A newer alternative to BCLs are corneal collagen shields (CSs), developed in 1984 by Fyodorov with the original purpose of treating corneal epithelial damage.2 CSs perform similar tasks to BCLs and prior studies suggest that CSs may be more effective in absorbing therapeutics and distributing them to the eye. In particular, a 1998 paper by O'Brien et al. found concentrations of tobramycin in the aqueous humor to be significantly higher with the use of CSs compared with BCLs 3 The differences in absorption and delivery of drug to the eye can be related to the properties of the materials. BCLs are made of hydrophilic polymers, whereas CSs are synthesized from a thin film of highly purified bovine collagen which has been cross-linked.

Endophthalmitis is a serious complication of cataract surgery with reported rates ranging from 0.06% to 0.286%.4–7 According to the 2014 American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery (ASCRS) member survey, a majority of clinicians use topical antibiotic drops as prophylaxis against endophthalmitis.8 However, difficulty with patient compliance with eye drops after cataract surgery has been well documented in the literature, including drops missing the eye (31.5% in a prospective cross sectional study by An et al.)9 and discontinuing drops prematurely.10 The 2014 ASCRS survey reported 1% of clinical practices use collagen shields soaked in antibiotics in conjunction with patient-administered antibiotic drops.8 In fact, a retrospective cohort study by Wallin et al. found that failure to place collagen shield soaked in antibiotics was correlated with a statistically significant increase in endophthalmitis.11 Currently, the most commonly used antibiotics in the prevention of endophthalmitis after cataract surgery are 4th generation fluoroquinolones including gatifloxacin and moxifloxacin (brand name Vigamox). In particular, moxifloxacin has been shown to have superior ocular potency and penetration and has the advantage of being free of the preservative benzalkonium chloride.12

Animal studies have evaluated the use of tobramycin, gentamycin and vancomycin in presoaked CSs.3,13,14 Specifically, tobramycin was found to have establish concentrations in the cornea and aqueous humor higher than the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for strains of Pseudomonas spp,14 and to achieve greater intraocular concentrations compared to drops alone.13 Furthermore, the CS group had a significant increase in concentration of tobramycin in the anterior chamber compared to BCLs and controls.3 Few studies have been conducted with fourth generation fluoroquinolones such as moxifloxacin. Hariprasad et al. demonstrated that CSs soaked in 0.5% moxifloxacin and applied prior to intraocular surgery resulted in lower concentrations in human aqueous compared to topical drops.15,16 In contrast, Haugen et al. demonstrated CSs soaked in gatifloxacin and moxifloxacin achieved similar results to topical drops using a rabbit animal model.17 Kleinman et al used the rabbit model to study CSs soaked in gatifloxacin and moxifloxacin and found sufficient concentrations of drug in the anterior chamber 6 hours after placement on the ocular surface, specifically that concentrations exceeded the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) 90 of most bacteria responsible for endophthalmitis (∼0.2 μg/ml).18,19

Many studies have investigated the uptake and release of moxifloxacin from conventional hydrogen and silicone hydrogen contact lenses.20–23 To our knowledge, no prior studies have compared diffusion of moxifloxacin in BCLs vs CSs or measured the overall drug delivery of moxifloxacin. Using our in vitro models, we sought to 1) investigate diffusion of moxifloxacin through BCLs vs. CSs, 2) evaluate the relative ability of BCLs and CSs to absorb and release moxifloxacin over time, and 3) estimate the potential release of moxifloxacin in the clinical setting.

Materials and Methods

BCL and CS Diffusion Assay

BCLs used in this study were from Air Optix Night and Day Aqua, power -0.00D, diameter 13.8 mm, composed of lotrafilcon A (Ciba Vision, Deluth, GA). Twelve-hour soft shield collagen corneal shields were kindly donated by Oasis Medical Inc (Catalog # 7012, Glendora, CA). The diffusion assay described by Zambelli et al.24 was followed with the exception of using a 12-mm rubber gasket to support the BCL and CS. Briefly, BCLs and CSs were placed concave side up on a 12-mm ring support in a 6-well tissue culture dish containing 0.45 μm filter inserts with 1 ml PBS in the well below the filter. Forty-microliters of moxifloxacin dissolved in water with glacial acetic acid (6%) prepared at a concentration of 50 mg/mL (5%moxifloxacin) (#M5794, LKT laboratories, St. Paul, MN) were added to BCLs and CSs. Twenty-microliter aliquots were taken at 0, 15, 30, 60, 120, and 1140 minutes and read at 293 nm, the absorbance maxima for moxifloxacin as previously reported.25 The 20 μl aliquots of the PBS below the filter were transferred to a 96-well UV plate (Costar 3635, Corning Inc.) into wells containing 180 μl of PBS. The solutions were then assayed using a Biotek Synergy II (Winooski, VT) spectrophotometer microreader plate (A=293 nm). In this and all subsequent experiments, the concentration of moxifloxacin was calculated by correlating experimental values to a standard curve. In all cases, the R value was greater than 0.97 and measured values were within the linear range of the assay. All samples were incubated at room temperature.

BCL and CS Release Assay

CSs and BCLs were equilibrated in PBS for 5 minutes at room temperature, during which an 18-gauge stainless steel wire skewer was inserted through the lens or shield for easy transfer. To measure drug release, CSs and BCLs were soaked in 0.5% moxifloxacin for 10 minutes at room temperature, rinsed briefly in PBS to remove excess moxifloxacin, then transferred to 1 ml of PBS in a UV cuvette (Brand Inc. product #759170, South Hamilton, MA) for spectrophotometric readings. The BCLs and CSs were removed from the cuvette during each reading and promptly replaced immediately thereafter. Moxifloxacin release was measured at an absorbance of 293 nm using a Biotek Synergy II spectrophotometer at 30 seconds, 2, 5, 10, 30, 60, and 120 minutes. The concentration of moxifloxacin was calculated by correlating experimental values to a standard curve.

Vigamox Release Assay

This assay was designed based on the use of CSs during cataract surgery by a corneal specialist at the University of Pittsburgh Department of Ophthalmology. CSs were soaked in either 500 microliters of PBS or 10 drops Vigamox (moxifloxacin HCl ophthalmic solution, 0.5% as base) (Alcon, Fort Worth, TX) for 15 minutes. A skewer was then inserted through each shield for easy transfer. Each CS was flicked and dabbed on Kimwipes (Kimberly-Clark, Irving, TX) to remove excess moxifloxacin before being transferred to 2 mL PBS in a UV cuvette. The CS on skewer were used to mix the solution prior to collecting samples at 10 seconds, 1, 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60 and 1440 minutes. From time 0-60 minutes, the cuvette was stored at room temperature; from 60 to 1440 minutes, they were stored at 30°C. At each time point 10 μl of CS solution were transferred to a 96-well UV plate (Costar 3635, Corning Inc.) into wells containing 90 μl of PBS. The solutions were then assayed using a BioTek Synergy II spectrophotometer microplate reader where absorbance for the solution was measured at 293 nm. At least 7 independent replicates of the experiment were performed on 5 separate days.

The authors noted that 12-hour CSs remained intact even after 24 hours of incubation in PBS. Further experiments were conducted to explore whether additional drug could be released from the CS. First, mechanically grinding of the CS was performed. A control CS and CS soaked in Vigamox were each placed in separate cuvettes with 2mL of PBS solution. The Bio-Gen PRO200 Homogenizer (Pro Scientific, Oxford CT) was used in each cuvette separately to grind the CS. Second, enzymatic digestion of the CSs was performed with Proteinase K. A CSs soaked in Vigamox were placed in separate wells of a contact lens case. To the control CS, 1 mL of PBS solution was added. To the experimental CS, 900 μl of PBS was added with 100 μl Proteinase K 20mg/mL (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Each CS was incubated in solution for 20 hours, at the end of which, the PBS CS was largely intact and the CS in proteinase K had completely dissolved. In each of the two supplemental studies, 10 μl of the CS solution were transferred to a 96-well UV plate into wells containing 90 μl of PBS the absorbances at 273 nm were read in a spectrophotometer.

All data and statistical analysis were performed with Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Office, Redmond, WA) and Graphpad Prism software (Graphpad, La Jolla, CA).

Results

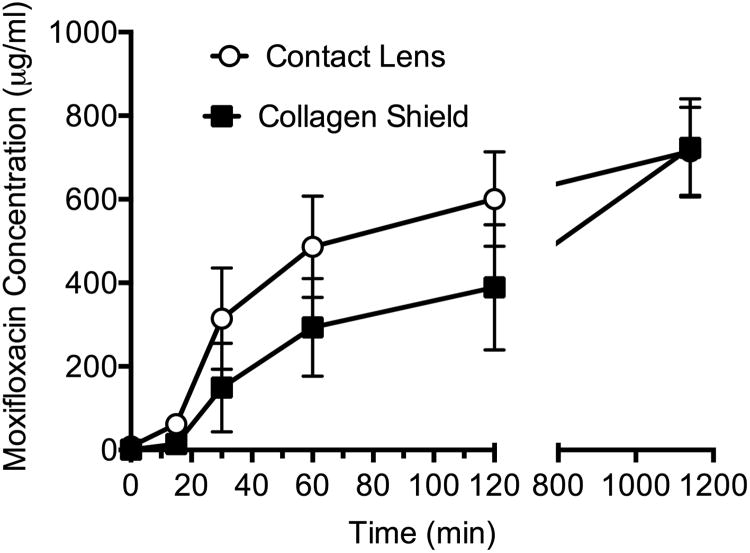

Using the diffusion assay, the penetration of moxifloxacin through BCLs and CSs were measured over time. Moxifloxacin diffusion was detectable at 6 time points and concentrations increased over time. Initially, diffusion through BCL appears to be more rapid than diffusion through CS. Based on starting concentration of 5% (50,000 μg/ml) and final concentrations of 714.9 ± 210.8 μg/ml in BCL group and 723.3 ± 235.2 μg/ml in the CS group, the percentage of drug that diffused through the BCLs and CSs were calculated. It was determined that 35.7 ± 10.5% of moxifloxacin diffused through the BCLs and 36.2 ± 11.8% diffused through the CSs (P=0.77, two-tailed unpaired Student's t test, Excel software). At the 1140 min time point, there was no statistical difference between the percentages of moxifloxacin diffused through BCL vs CS (Figure 1). Though the trend is for better diffusion through the CSs, there was no significant difference in diffusion of moxifloxacin through BCL vs CS.

Figure 1.

Diffusion of moxifloxacin across BCL and CS (up to t=1140 min), mean with SEM bars

Using the moxifloxacin release assay, the concentration of moxifloxacin released was compared between BCLs and CSs soaked in moxifloxacin and measured over a total of 7 time points over 120 min (Figure 2). In this assay, both the BCLs and CSs were equilibrated in PBS before being soaked in moxifloxacin. At each time point, the concentration of moxifloxacin released from the CS was greater than from the BCL. At 120 min, a total of 33.3 ± 6.77μg/ml was released from BCLs compared to 45.8 ± 5.2 μg/ml from the CSs (p= 0.0008, two-tailed unpaired Student's t test, Excel software). This assay demonstrates the release of moxifloxacin was significantly greater from CSs than from BCLs.

Figure 2.

Release of moxifloxacin from BCL and CS (up to t=120 min), mean with SEM bars

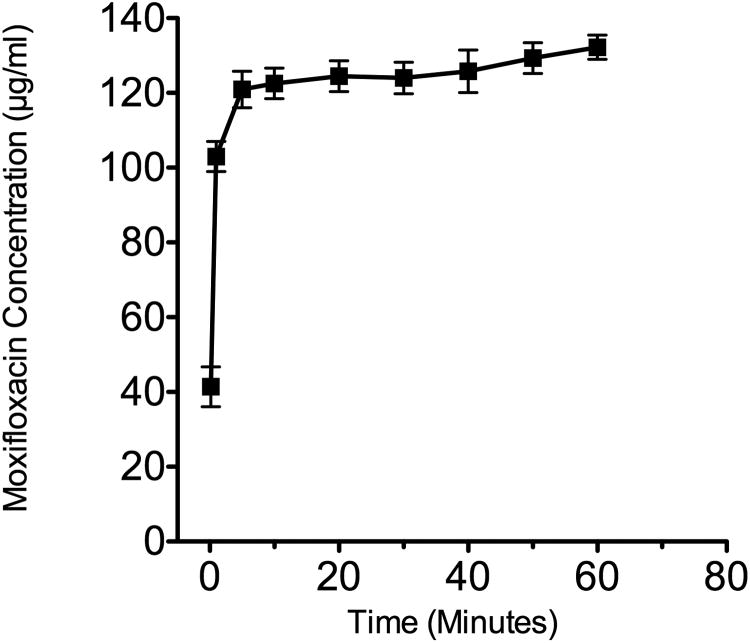

The moxifloxacin release assay was modified to reflect the clinical use of Vigamox-soaked CSs. Therefore, Vigamox (0.5% moxifloxacin in specific buffer solution) rather than moxifloxacin in glacial acetic acid was used in the experiment. Control analysis of CS soaked in 500 μl of PBS was repeated two times and each time demonstrated negligible absorbance over the study period, indicating that the CSs by themselves did not cause false positive readings. The release of moxifloxacin as measured by the absorbance (293 nm) and demonstrates that the majority of moxifloxacin in released from CS within the first 5 min (Figure 3). The concentration of moxifloxacin released into a 2 mL volume was measured over 10 time points over 24 hours. Based on the final concentration of the solution, the maximum concentration of moxifloxacin reached after 24 hours was a mean of 127.7 ± 7.25 μg/ml. Mechanical grinding or enzymatic digestion of the shields did not increase the amount of measured moxifloxacin, indicating that moxifloxacin was not sequestered within the CS.

Figure 3.

Release of moxifloxacin from Vigamox-soaked CS (up to t=60 min), mean with SEM bars

Discussion

Endophthalmitis is one of the most feared complications of cataract surgery. The most common pathogen is Staphylococcus epidermidis26–28. Fourth generation fluoroquinolones are among the most widely used antibiotics in prophylaxis for endophthalmitis in cataract surgery.8 Kowalski and colleagues found that topical antibiotic therapy with Vigamox before and after intraocular bacterial challenge can prevent bacterial endophthalmitis in the rabbit model.29 Difficulties with patient compliance in the administration of eye drops has led clinicians to seek alternatives to traditional topical antibiotic prophylaxis. Furthermore, in a typical 50 μl drop, only 1-7% of the medication is absorbed into the eye given loss of drop through blinking, dilution by reflex tearing, and drainage through the tear duct.30 Collagen shields are a promising solution because of their ability to serve as a drug depot that delivers therapy over time and also their ability to aid in the promotion of corneal epithelial and stromal healing. We performed in vitro testing to investigate the effectiveness of moxifloxacin soaked CS to supplement antibiotic delivery to the post-op cataract eye in additional to traditional drops.

In the diffusion assay, a higher concentration of moxifloxacin (5% versus 0.5%) was used to maximize the sensitivity of the assay and to ensure there was a detectable outcome. We found no difference in the diffusion of moxifloxacin through BCLs and CSs. However, the release assay showed greater deliverance of moxifloxacin from CSs than BCLs. It is important to note that only one type of silicone hydrogel contact lens was used, this particular one made from lotrafilcon A. Given that contact lenses made of different materials have been found to have varied properties in the absorption and release of drug20, the results of our comparison may only pertain to this particular type of contact lens.

In vitro experiments were conducted to simulate clinical application of Vigamox-soaked CS. The incubation time of CSs in Vigamox of 15 minutes is based on the clinical practice at our institution. While it would have been ideal to incubate the CS-PBS solutions at 30°C the entire 24 hours to simulate the temperature of the human corneal surface, the solution was kept at room temperature during the 1st hour due to the need to obtain frequent samples. The experiments found the concentration of moxifloxacin released of 127.7 ± 7.25 μg/ml in 2mL PBS over 24 hours. This concentration was well above the MIC90 of S. epidermidis, the most common cause of endophthalmitis.31 Considering that clinically the collagen shield is bathed in around 7-8μl tear film32 rather than 2mL of PBS, the diffusion rate of the antibiotic out of the CS should be slower in vivo. Our data indicate that the CSs have the potential to soak up and release approximately 250 μg of moxifloxacin. Assuming that 1 drop is 50 μl of solution, then 1 drop 0.5% moxifloxacin contains approximately 200 μg of moxifloxacin. Less than 1-7% of each eye drop is delivered to the eye30, and is around 2-14 μg, which is quickly diluted with additional tears and drained through the lacrimal system. In fact, the average effective time for most eye drops on the ocular surface is only 2-5 minutes.33 Extrapolating from our data, 250 μg/ml in 7-8 μl of the tear film is around 2 μg of medication that the eye is constantly bathed in. Therefore, CSs have the potential to deliver a similar amount of drug at a more constant rate than simply administering a single eye drop, while serving as a mechanical barrier to bacteria entry.

Hariprasad et al. conducted a clinical study by recruiting patients to receive pars planar vitrectomies.15,16 Ten patients were randomized to groups of 5 to either receive 24-hour collagen shields to be placed for 4 hours prior to surgery or 24 hours prior to surgery. Another group of 20 patients were randomized to administer drops at either every 2 hours or every 6 hours for 3 days prior to surgery. Samples of aqueous and vitreous humor were collected intraoperatively. They found concentrations of topical moxifloxacin could reach appropriate concentrations in the aqueous humor, but not the vitreous. Furthermore, collagen shields delivered considerably less antibiotic to both fluid cavities. We postulate that intraoperative corneal incisions could lead to greater aqueous and vitreous concentrations of moxifloxacin than were detected in the study by Hariprasad et al. Additionally, this earlier study used 24-hour dissolution collagen shields which are cross-linked, whereas our study used the 12-hour non-crosslinked dissolution collagen shield.

In a study by Haugen et al, the use of Zymar (3mg/ml gatifloxacin), Tequin (10mg/ml gatifloxacin), and Vigamox (5mg/ml moxifloxacin) in topical drop form and soaked-CS form were compared in their ability to lower the incidence of endophthalmitis in the rabbit model. The study demonstrated 4th generation fluoroquinolones gatifloxacin and moxifloxacin as topical drops were similarly effective as the collagen shield delivery of the medications in preventing endophthalmitis. This assumes perfect topical drop compliance.

There are limitations to our study given that an in vitro experiment is unable to fully simulate the clinical environment of the post-cataract surgery eye. Firstly, the tear film of the typical eye contains around 7-8μl of fluid which would bathe the collagen shield; whereas, in our study environment, the CS is bathed in 2mL of PBS solution. Furthermore, studies investigating the absorption and release of drugs from contact lenses have found significant differences in release of drug when the contact lens is placed in static solution in a vial compared to a model incorporating fluid flow and mechanical rubbing to simulate blinking.20,22,34 In fact, multiple publications have described drug release from contact lenses in static vials as a burst followed by plateau within 1 hour. On the other hand, models incorporating fluid flow or mechanical rubbing produced a more constant release of drug over 24 hours.

Next, our model does not include proteolytic enzymes in the tear film and the mechanical breakdown during blinking, both of which are thought to be the mechanism for dissolution of CS on the ocular surface. In fact, CS soaked initially in Vigamox and then placed in 2mL PBS continues to be intact even after 14 days in solution based on samples which were kept after our initial experiments. Finally, in clinical practice, the patient would be instructed to administer antibiotic and corticosteroid drops on top of the CS placed on the post-operative eye. Our model is unable to take this into account. Despite the limitations, our study allows us to make conclusions based on the potential concentration of moxifloxacin released by BCLs and CSs and diffusion of this important fluoroquinolone through BCLs and CSs.

In summary, in our study model moxifloxacin diffuses through the Air Optix Night and Day Aqua BCL and CSs at similar rates, however the CS has greater capacity to absorb and release moxifloxacin compared to BCL. In the in vitro model, Vigamox soaked CSs released 250 μg of moxifloxacin, and may therefore be a useful method to prevent endophthalmitis given limitations in the ocular delivery of eye drops, and particularly in patients who are unreliable at administering drops. It is important to note that the collagen shield could fall out early, and therefore may be best used as an adjunct to topical drops or intraocular antibiotic instillation. Additional studies are warranted to further characterize the delivery of moxifloxacin through CS in the prophylaxis of endophthalmitis after cataract surgery.

Acknowledgments

Sources of financial support: Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc., New York, New York; NIH grant EY024785, NIH grant AI085570, NIH Core Grant EY08098, Material Disclosures: Collagen shields were kindly donated by Oasis Medical

Footnotes

None of the authors has a financial or proprietary interest in any material of method mentioned

References

- 1.McDermott ML, Chandler JW. Therapeutic uses of contact lenses. Surv Ophthalmol. 1989;33(5):381–394. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(89)90015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Willoughby CE, Batterbury M, Kaye SB. Collagen corneal shields. Surv Ophthalmol. 2002;47(2):174–182. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(01)00304-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Brien T, Sawusch M, Dick J, Hamburg T, Gottsch J. 1988. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1988;15(5):505–507. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(88)80007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Javitt JC, Street DA, Tielsch JM, et al. National outcomes of cataract extraction. Retinal detachment and endophthalmitis after outpatient cataract surgery. Cataract Patient Outcomes Research Team. Ophthalmology. 1994;101(1):100–5. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(13)31251-2. discussion 106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Javitt JC, Vitale S, Canner JK, et al. National outcomes of cataract extraction. Endophthalmitis following inpatient surgery. Arch Ophthalmol (Chicago, Ill 1960) 1991;109(8):1085–1089. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1991.01080080045025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jensen MK, Fiscella RG, Crandall AS, et al. A retrospective study of endophtalmitis rates comparing quinolone antibiotics. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;139(1):141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taban M, Behrens A, Newcomb RL, et al. Acute endophthalmitis following cataract surgery: a systematic review of the literature. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123(5):613–620. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.5.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang DF, Braga-Mele R, Henderson BA, Mamalis N, Vasavada A. Antibiotic prophylaxis of postoperative endophthalmitis after cataract surgery: Results of the 2014 ASCRS member survey. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2015;41(6):1300–1305. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2015.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.An JA, Kasner O, Samek DA, Lévesque V. Evaluation of eyedrop administration by inexperienced patients after cataract surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2014;40(11):1857–1861. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2014.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hermann MM, Ustündag C, Diestelhorst M. Electronic compliance monitoring of topical treatment after ophthalmic surgery. Int Ophthalmol. 2010;30(4):385–390. doi: 10.1007/s10792-010-9362-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wallin T, Parker J, Jin Y, Kefalopoulos G, Olson RJ. Cohort study of 27 cases of endophthalmitis at a single institution. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2005;31(4):735–741. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2004.10.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Brien TP, Arshinoff SA, Mah FS. Perspectives on antibiotics for postoperative endophthalmitis prophylaxis: Potential role of moxifloxacin. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2007;33(10):1790–1800. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2007.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen C, Takruri H, Duzman E. Enhancement of the ocular bioavailability of topical tobramycin with use of a collagen shield. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1993;19(2):242–245. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(13)80949-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Unterman SR, Rootman DS, Hill JM, Parelman JJ, Thompson HW, Kaufman HE. Collagen shield drug delivery: therapeutic concentrations of tobramycin in the rabbit cornea and aqueous humor. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1988;14(5):500–504. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(88)80006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hariprasad SM, Shah GK, Chi J, Prince RA. Determination of aqueous and vitreous concentration of moxifloxacin 0.5% after delivery via a dissolvable corneal collagen shield device. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2005;31(11):2142–2146. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2005.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hariprasad SM, Mieler WE, Shah GK, et al. Human intraocular penetration pharmacokinetics of moxifloxacin 0.5% via topical and collagen shield routes of administration. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2004;102:149–55-7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haugen B, Werner L, Romaniv N, et al. Prevention of endophthalmitis by collagen shields presoaked in fourth-generation fluoroquinolones versus by topical prophylaxis. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2008;34(5):853–858. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kleinmann G, Larson S, Neuhann IM, et al. Intraocular concentrations of gatifloxacin and moxifloxacin in the anterior chamber via diffusion through the cornea using collagen shields. Cornea. 2006;25(2):209–213. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000170689.75207.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kleinmann G, Larson S, Hunter B, Stevens S, Mamalis N, Olson RJ. Collagen shields as a drug delivery system for the fourth-generation fluoroquinolones. Ophthalmologica. 2006;221(1):51–56. doi: 10.1159/000096523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bajgrowicz M, Phan CM, Subbaraman LN, Jones L. Release of ciprofloxacin and moxifloxacin from daily disposable contact lenses from an in vitro eye model. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56(4):2234–2242. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-16379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kakisu K, Matsunaga T, Kobayakawa S, Sato T, Tochikubo T. Development and efficacy of a drug-releasing soft contact lens. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54(4):2551–2561. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-10614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phan CM, Bajgrowicz-Cieslak M, Subbaraman LN, Jones L. Release of Moxifloxacin from Contact Lenses Using an In Vitro Eye Model: Impact of Artificial Tear Fluid Composition and Mechanical Rubbing. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2016;5(6):3. doi: 10.1167/tvst.5.6.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharma J, Majumdar DK. Moxifloxacin loaded contact lens for ocular delivery-an in vitro study. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2012;4(1):4–8. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zambelli AM, Brothers KM, Hunt KM, et al. Diffusion of Antimicrobials Across Silicone Hydrogel Contact Lenses. Eye Contact Lens Sci Clin Pract. 2015;0(0):1. doi: 10.1097/ICL.0000000000000121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anees MI, Baig MS, Tathe A, Bagh R. Determination of Cefixime and Moxifloxacin in pharmaceutical dosage form by simultaneous equation and area under the curve UV-spectrophotometric method. World Jounrla Pharm Pharm Sci. 2015;4(3):1172–1179. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Han DP, Wisniewski SR, Wilson LA, et al. Spectrum and susceptibilities of microbiologic isolates in the Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996;122(1):1–17. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)71959-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benz MS, Scott IU, Flynn HW, Unonius N, Miller D. Endophthalmitis isolates and antibiotic sensitivities: A 6-year review of culture-proven cases. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137(1):38–42. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(03)00896-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rarey KA, Shanks RMQ, Romanowski EG, Mah FS, Kowalski RP. Staphylococcus aureus Isolated from Endophthalmitis Are Hospital-Acquired Based on Panton-Valentine Leukocidin and Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2012;28(1):12–16. doi: 10.1089/jop.2011.0107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kowalski RP, Romanowski EG, Mah FS, Yates KA, Gordon YJ. Topical prophylaxis with moxifloxacin prevents endophthalmitis in a rabbit model. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;138(1):33–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ghate D, Edelhauser HF. Barriers to glaucoma drug delivery. J Glaucoma. 2008;17(2):147–156. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e31814b990d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stroman DW, Dajcs JJ, Cupp GA, Schlech BA. In vitro and in vivo potency of moxifloxacin and moxifloxacin ophthalmic solution 0.5%, a new topical fluoroquinolone. Surv Ophthalmol. 2005;50(6 SUPPL. 1) doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mathers WD, Daley TE. Tear flow and evaporation in patients with and without dry eye. Ophtha. 1996;103(4):664–669. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(96)30637-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gulsen D, Chauhan A. Ophthalmic Drug Delivery through Contact Lenses. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:2342–2347. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tieppo A, Pate KM, Byrne ME. In vitro controlled release of an anti-inflammatory from daily disposable therapeutic contact lenses under physiological ocular tear flow. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2012;81(1):170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2012.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]