Abstract

A key mechanism of risk transmission between maternal risk and child outcomes are the mother's representations. The current study examined the effects of an attachment-based, trauma-informed parenting intervention, the Mom Power (MP) program, in optimizing maternal representations of high-risk mothers utilizing a randomized, controlled trial design (NCT01554215). High-risk mothers were recruited from low-income community locations and randomized to either the MP Intervention (n=42) or a control condition (n=33) in a parallel design. Maternal representations were assessed before and after the intervention using the Working Model of the Child Interview. The proportion of women with Balanced (secure) representations increased in the MP group but not in the control group. Parenting Reflectivity for mothers in the treatment group significantly increased, with no change in the control condition. Participation in the MP program was associated with improvements in a key indicator of the security of the parent-child relationship: mothers' representations of their children.

Keywords: attachment, maternal representations, parenting, intervention research, randomized, controlled trial

Improving Maternal Representations in High-Risk Mothers: A Randomized, Controlled Trial of the Mom Power Parenting Intervention

A plethora of research over the past several decades has demonstrated that children whose mothers have experienced trauma and/or who struggle with mental illness are at increased risk for insecure attachments, cognitive and functional impairments, and behavioral and emotional problems [1-4]. One of the hypothesized mechanisms of transmission between parental psychopathology and child outcomes is maternal representations, or a mother's perceptions, expectations, and subjective experience of parenting and of her child. Maternal representations are crucially important in the development of the attachment relationship [5], and the quality of the attachment between a caregiver and her child in the first years of life is central to a child's later functioning (e.g. [6]). High-risk mothers, such as those who have experienced trauma, are more likely to have non-balanced representations and insecurely attached children [7, 8]. Given this link between non-balanced representations and poor child outcomes among at-risk parents, it is particularly important to target such non-balanced representations through interventions intended to facilitate the development of balanced and secure parental representations. Thus, in the specific case of mothers with experiences of trauma and psychopathology, there has been a critical need for targeted, preventive interventions to address such non-balanced representations. The current study examined the effects of one such intervention, the Mom Power program [9-11], on maternal representations in a randomized, controlled trial.

Maternal Representations

Central to attachment theory is the concept of internal working models, or an individual's mental representation of relationships [12]. In the context of early parent-child relationships, the mechanism for understanding the interplay between a parent's own early experiences, her parenting behavior, and the nature of the relationship between herself and her child is captured in her representations of her child. Attachment theory posits that in addition to understanding the behavioral patterns and interactions between a parent and child, such as sensitivity and responsiveness, it is also essential to understand the parent's subjective experience of her child. These representations include the meaning of the relationship to the parent, the caregiving she received as a child, her past and current trauma, and her expectations for herself as a parent and for her child. Maternal representations shape the attachment relationship, both in their effect on maternal sensitivity/responsiveness and independent of this mediational pathway [13, 14]. Importantly, attachment theory suggests that maternal representations are dynamic and can be revised in response to later relationship experiences or targeted intervention [15].

Several interview measures have been developed that examine parents' internal representations of their specific relationships with individual children ([16] [17], [18] [19] ). These semi-structured interviews are designed to capture parents' perceptions and subjective experience of their child's personality and their relationship with their child. Representations have been associated with both adult attachment states of mind and observed parenting behavior [20], as well as infant attachment classifications [5]. One of the most commonly used and well-validated measure is the “Working Model of the Child Interview” (WMCI; [21-23]). The coding of responses to the WMCI yields three main typology classifications [24]: Balanced, Disengaged, and Distorted. Balanced representations are characterized by narrative coherence and richly elaborated descriptions, emotional warmth, acceptance of the child and sensitive responsiveness to the child's needs. Although parents in this category may express feelings of challenge or difficulty in parenting, such concerns do not overwhelm or dominate their perceptions of their children. Characteristic of the emotion/cognition regulation style in this category is an ability to access a range of emotions, without a need to minimize or be overwhelmed by feelings regarding their children and parenting. Prior research has demonstrated that a balanced WMCI typology is associated with more sensitive parenting and a greater likelihood of secure attachment among offspring [5] [25] [26]. Disengaged representations are characterized by an emotional distance and a sense of ‘aloofness’ in regards to the child. Parents in this category often have less to say about their child, and/or are more likely to describe their children in a manner that minimizes affective involvement, suggesting a tendency to emotionally distance, reject and/or fail to acknowledge their children's emotional and dependency needs. Characteristic of the emotion/cognition regulation style in this category is an emotion-deactivating style. Prior research has demonstrated that the Disengaged WMCI typology is associated with less sensitive caregiving and a greater likelihood for insecure attachment among the offspring, and for Avoidant child attachment in particular [5] [27] [26]. Distorted representations are characterized broadly by a tendency to heighten affect and a poorly organized narrative that is low in overall coherence. Parents in this category often appeared confused or unsure about their relationship with their children, and/or are anxiously overwhelmed by their children's perceived needs and experiences. Some are distracted by other concerns, are self-involved, or are role reversed in their relationships with their children, for example, describing their young children as “buddies” or “confidants.” Characteristic of the emotion regulation among parents in this category was an emotion-overactivating style. Prior research has demonstrated that the WMCI Distorted typology is associated with less sensitive caregiving and a greater likelihood for insecure and/or disorganized child attachment [5] [26]. Research has also demonstrated that these typologies distinguish clinical from nonclinical samples of children [28] and mothers [21, 25] [27, 29, 30]. Mothers with psychopathology tend to have more unbalanced and distorted representations of their infants [8]. Thus, these mothers are a particularly appropriate target for attachment-based interventions.

Maternal psychopathology

A significant minority of new mothers struggle with mental health problems. As many as one fifth of women experience postpartum depression (19.2% mild or major depression, [31], and rates of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have been estimated at 3-13% [32]. A history of childhood maltreatment increases the chance of depression and PTSD [33, 34], as does current interpersonal violence [35]. A mother's symptoms of psychopathology, such as social withdrawal, anxiety, emotional lability, anhedonia, and fatigue, have been found to disrupt the interaction and the development of the relationship between mother and infant [36, 37]. Mothers with histories of trauma are more likely to have difficulties in bonding with their young infants [38], and are more likely to be intrusive or show frightened or frightening parenting behaviors [39]. Often, mothers with mental illness, specifically suffering depression and/or PTSD, are impaired in their ability to recognize infant signals of distress and react with appropriate sensitivity and responsiveness to their children's needs [40-43].

Children of these mothers tend to be more withdrawn and fussy [44, 45], have impaired biobehavioral affect regulation [43, 46], show more behavior problems [47, 48], and have more insecure and disorganized attachments [3, 7]. These factors as well as infant temperament can lead to a bidirectional, transactional effect between maternal psychopathology and child outcomes [49, 50].

Research on perinatal women with psychopathology has shown that treatment of the mother only (e.g. medication, individual psychotherapy) is not sufficient to address the negative impact of psychopathology on the child's development and attachment relationship [51-53]. Conversely, interventions that target parenting skills alone, without addressing the complex mental health and social needs of mothers are unlikely to be successful in a high-risk population [54, 55]. Rather, to exert the greatest effect, interventions should focus on both mental health/self-care and parenting from an attachment framework.

Impact of Attachment Based Interventions on Parenting Representations

As described, the child-parent attachment relationship can be assessed at multiple levels, including behavioral observation (e.g., the Strange Situation Procedure to assess child attachment classification) and representation (e.g., the story-stem tasks to assess child representations of attachment figures, or the Working Model of the Child Interview to assess parents' internal working models of their children) [56, 57]. Accordingly, a number of attachment-based interventions have been developed and tested in regards to outcomes reflecting improved observed caregiver sensitivity and child attachment classifications, for example, a brief home-visiting adaptation of the Circle of Security (COS) parenting intervention for infants [58] and Child Parent Psychotherapy [59].

Fewer studies have specifically focused on changes in parents' representations of their children and/or parenting, and most of these studies have involved “open trials” with no control group comparison. For example, Huber et al. [60] reported improved reflective functioning, assessed using a newly developed Circle of Security Interview (COSI), associated with participation in a COS intervention. While pre-post changes following completion of the 20-week individual COS intervention were both clinically and statistically significant, there was no randomization nor comparison group. Similarly, Schechter and colleagues [61] examined the effects of a video-feedback-based intervention (“CAVES”) and demonstrated improvement in reflective functioning among women, though again with no control or comparison group. Finally, a prior “open” trial (i.e., no control group) of Mom Power evaluated changes in reflective parenting associated with participation in this 13-session multifamily group intervention, and findings confirmed improvements in reflective parenting in Mom Power graduates [11].

Notable exceptions to the uncontrolled trial approach for testing change in representations are found in three randomized controlled trials (RCT), each of which utilized the Parent Development Interview (PDI) Reflective Functioning scale: (1) an attachment-based intervention for substance abusing mothers [62], (2) a recent study evaluating a brief, relationship-focused “Floortime” intervention for children with neurodevelopmental disabilities [63], and (3) a study of psychoanalytic parent-infant psychotherapy for mothers with mental illness who also experience social adversity and are parenting a young infant [64]. Both the Suchman, Decoste, Mcmahon, Rounsaville and Mayes [62] and Sealy and Glovinsky [63] studies demonstrated improvement in reflective functioning associated with intervention. While the Suchman study involved administration of the WMCI to assess overall classifications of the representation, there was insufficient change in these classification categories to demonstrate significant improvement; the overall level of functioning for these mothers was likely significantly impaired given the extremely high-risk nature of the substance-using sample. Indeed, even within the domain of Reflective Functioning, Suchman observed changes only in parent-focused, but not child-focused RF, suggesting that the intervention yielded less impact in changing parents' representations towards their children, but rather that the treatment effect reflected change in insight and capacity for reflective functioning in regards to the parents' own mental experience (e.g. thinking about their own relationships). Thus, neither of these RCT studies reported changes in the overall typology classifications of parents' representations of their children. Finally, the RCT examining impact of the psychoanalytically-oriented infant parent psychotherapy found no differences in treatment versus control group in regards to RF assessed via the PDI [64]. Taken together, extant data provide mixed evidence for changes in reflective functioning, and to date, a lack of a RCT study demonstrating change in representational security through a parenting intervention. To our knowledge, this is the first study evaluating whether a brief attachment-based parenting intervention delivered to high risk parents can improve the quality of parents' representations of their parenting and their children using a validated representational interview (WMCI) and stringent research criteria (RCT design, blinded coders).

Mom Power Intervention

Mom Power is an attachment-based intervention that aims to enhance sensitive and nurturing parenting, reduce caregivers' mental health problems, and promote balanced, positive attributions towards the child and parenting in high-risk mothers. It was developed by a subset of the current authors [9] and was designed to increase treatment engagement with an integrated focus on self-care/mental health and parenting competence, while at same time facilitating social support and access to care. A previous “open” trial (i.e. no control group) with 68 mothers completing Mom Power, found that the program decreased mothers' depression, PTSD, and caregiving helplessness, and improved parenting confidence, social support and connection to care [10, 11]. The Mom Power program is run in several community mental heath centers and psychiatry clinics, and is expanding in its dissemination.

Mom Power is based in attachment theory Bowlby [12] and trauma theory [65, 66], and aims to promote positive child trajectories by enhancing parent–child relationships. Several other attachment based interventions similarly target relationships to improve child outcomes (e.g. [67-71]), however these intervention models tend to involve one-on-one interactions with a clinician over long periods of time. Uptake and engagement can be especially challenging for such interventions, particularly home-based programs [72]. Mom Power, instead, utilizes a time-limited, multifamily group format to encourage participant engagement and retention, provide social support, and connect parents to further services as needed. In a nonjudgmental and accessible format, the curriculum presents evidence-based and theory-driven parenting and self-care concepts in interactive group sessions.

Mom Power's key treatment principles are safety, trust building, enhancing self-efficacy through empowerment and skill-building around self-care, problem solving, emotion regulation, and parenting. Mom Power accomplishes this by delivering five core components:

Enhancing peer/social support is accomplished by creating a shared group experience, with opportunities for informal relationship building among participants, as well as by inviting mothers to bring a “parenting partner” guest (e.g., the child's father, or mothers' spouse, friend, relative, or other key support person) to one of the sessions, thus also enhancing “buy in” from critical “others” in the mother's day-to-day environment.

The Attachment-Based Parenting Education curriculum emphasizes responsiveness and sensitivity to young children's separation and reunion experiences. The curriculum introduces key topics in parenting and child development; engagement in activities is designed to practice skills and reflect on interactions while also emphasizing attachment concepts in an effort to help mothers identify and address children's emotional needs.

Mental health and self-care practice teaches mothers how to reduce their own distress during emotionally evocative parenting moments and how to recognize their own emotional dysregulation such as depression and trauma-related anxieties. To help mothers build a “self-care toolkit,” each group session ends with hands-on practice of one evidence-based stress-reduction “skill” including guided breathing, visualization, relaxation, or mindfulness.

Guided parent–child interactions emphasize creating safe and predictable routines for both mother and child. When mothers leave for their group sessions, “goodbyes” are acknowledged and reunions are anticipated using songs or games. Children learn that it is “safe” to be left briefly because their mothers will come back if they need comfort. At reunion, the group facilitators are able to observe and support reunions in “real time” and help mothers recognize and respond to their children's emotional needs in that moment. Mothers are encouraged to anticipate, observe, and reflect upon these separations and reunions, as well as identify ways they might want to “try something new” to address their children's feelings during separation/reunion.

Connecting to care involves identifying and connecting women to ongoing care beyond the Mom Power program (if this is indicated), which is a critical component of the model. During the individual sessions (midway and at the end of the group), the facilitators have the opportunity to discuss unresolved areas of challenge and to provide individualized, tailored information for connecting mothers to services in their communities. The facilitators are very hands-on; for example, they make phone calls with the mothers to community agencies and problem-solve potential barriers to engagement.

Mom Power uses a metaphor of a tree to illustrate the parent's role in creating a secure base and safe haven from which children can explore, connect, thrive and grow. Within this metaphor parents gain understanding of children's capacity to learn and grow at times when they feel safe to explore. The program helps parents identify these periods and provide a secure base from which children can “branch out.” At times when children are distressed or have active attachment needs, Mom Power helps parents to provide a safe haven and meet these needs. They do so by providing moments of connection that build and strengthen the “roots,” providing greater support and stability for subsequent development. The sun in the Tree metaphor represents the warmth, joy and delight that children need from their parents whether they are in moments of exploration (“branching out”) or connection (“building roots”). Throughout the course of Mom Power groups, parents learn to apply the Tree concepts to caregiving situations. Further, parents have the opportunity to practice separations and reunions in sessions, as they leave for the parent group and subsequently reunite with children. This ‘in vivo’ experience elicits attachment-relevant behaviors and representations in a supportive environment, and the curriculum actively encourages them to experiment with new ways of relating to their children and to put into practice the skills they are learning in class during these separations and reunions. Mom Power encourages mothers to increase reflective capacity and gain insight through supportive exposure to attachment-based parenting principles. While manualized, the curriculum is highly individualized, interactive and experiential, and delivered in a group format meant to create a welcoming, trust-building atmosphere.

In addition to adhering to the core components outlined here, the Mom Power program also combats structural barriers to engagement identified in prior research by providing weekly transportation to and from group sessions, a shared meal during group sessions, and no-cost childcare, as an integral part of the Mom Power model [38, 73].

Aims of the current study

The present study sought to test the hypothesis that maternal representations of their children, reflected by WMCI typologies and Parenting Reflectivity scores, would improve from baseline- to follow-up, but only for women who were randomly assigned to the Mom Power treatment condition. This is, to our knowledge, the first study to examine the impact of a group attachment-based parenting intervention on maternal representations in a randomized controlled trial.

Methods

This study was approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board; written, informed consent was obtained from all adults, and each mother received compensation for their involvement in data collection during study participation. The trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT01554215.

Participants & Recruitment

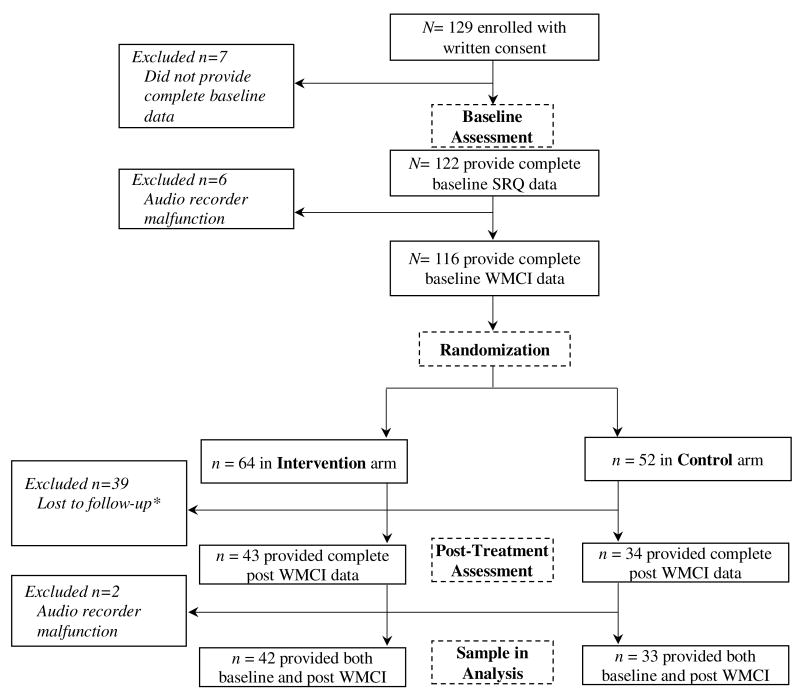

Participants in the study were mothers who either self-referred in response to fliers posted in low-income community locations (e.g., child care facilities, WIC offices, women's shelters), primary care clinics (family medicine, pediatrics, and OB/GYN), and community mental health clinics, or were provided a referral by their primary care or mental health providers. Recruitment materials invited mothers to participate in a research project investigating the benefit of a ‘parenting and self-care’ group. Recruitment took place between September, 2011 and May, 2012. Eligible mothers provided informed written consent and were enrolled into the study (N= 129). Inclusion criteria were: at least 15-years-old, English-speaking, pregnant or having at least one child in age range of 0- to 5-years-old. Interested and eligible mothers engaged in an initial phone call with research staff and the study was described; during this call mothers were informed that once they consented to the study and underwent the baseline assessment they would be randomized either to a weekly multifamily group [Mom Power Intervention] condition or a weekly mailing [Control] condition. Of the women initially enrolled, 122 women provided complete baseline self-report questionnaire (SRQ) data collected at a home visit. Of those, a total of 116 women also completed baseline WMCI interview data. Sixty-four women were allocated to the Intervention condition and 52 to the control condition (see randomization process below); of these women, 75 have both baseline and post-intervention WMCI interviews (42 Intervention and 33 control) with complete codes (see Figure 1). Reasons for not having completed coded WMCI include technical problems (e.g., audio recorder technical errors), administrative problem (e.g., ran out of time during assessment visit), or participant lost to follow up (e.g., family relocated, unable to reach family, or parent returned to work and unable to continue).

Figure 1.

Participant recruitment and randomization flowchart.

*No post-treatment assessment due to change of contact, unable to contact/schedule

Procedure

Assessments

A pre-trial baseline and a post-trial exit assessment were performed either in the participant's home or, if preferred, at the primary care/mental health office. At the baseline visit, study staff reviewed study protocol, answered any questions about study participation, and obtained written consent from the mother. Mothers then completed a set of self-report questionnaires including a demographic survey, self-report measures of depression and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and completed a standard semi-structured interview regarding their perceptions of the target child and of themselves as a parent (the WMCI). The interview was audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim for later coding. The exit assessment followed the same protocol as the baseline visit; in addition, women provided satisfaction ratings about the multifamily group experience. Women received two $20 payments for completion of survey data during the baseline and the exit visit.

Randomization

Following completion of the baseline assessment, women were randomized in a parallel design using a computer-generated algorithm (using urn randomization; [74, 75]). This specific type of randomization design is used with small samples to assure that certain key characteristics such as, in this case, maternal trauma-exposure and depression, are equal across both groups. Randomization occurred in blocks of 10 with equal allocation after completion of the baseline assessments. Based on this, participants were assigned to either attend the 10-week Mom Power group intervention (treatment condition) or receive informational packets in the mail (mailing control condition). Women were informed of their group assignment via phone call within 1 week of the baseline assessment. All women randomized into the control arm were informed that they would be provided the opportunity to participate in the multifamily group free of charge after the study end.

Intervention Condition

Women randomized to the Intervention arm received the 13-session Mom Power intervention (3 individual sessions and 10 group sessions) led by community clinicians trained in the model (see below training and fidelity). Individual sessions were held at participant's home or an office (based on preference), and occurred before, midway through, and post 10 weeks of group sessions. Groups were held at community locations (e.g., churches) or primary care sites, and were co-facilitated by two interventionists, at least one being a Master's level clinician. On average, group size included 8-10 mothers. Mothers received $5 each week as a transportation incentive for group participation. For attending at least 7 of the 10 group sessions mothers were compensated an additional $15 and received a graduation certificate.

Training and fidelity in MP model

Community clinicians of partnering local agencies underwent a 3-day in-person manualized training. The intervention is manualized and both individual and group sessions follow a written curriculum. Model fidelity is supported by weekly reflective supervision. Group sessions were video-taped for later fidelity coding utilizing a fidelity monitoring scale that indexes 12 criteria to evaluate whether facilitators adhered to core components of the MP intervention in regards to content and framework. Each of the 12 criteria are scored on a Likert-scale (ranging from 1-5), with 5 representing the highest and 1 the lowest level of fidelity. The content subscales index fidelity to the manual (e.g., following the presenting the activities as written). The framework subscales index whether facilitators succeeded in setting a therapeutic framework (e.g., creating a welcoming atmosphere, maintaining charge of the group while also responding to concerns). A random sample of 20% of all sessions were scored for fidelity. Summary content and framework subscale scores were computed by averaging item responses on the two subscales. On average, the groups received a content subscale score of 4.02 (SD = .72) and framework subscale score of 3.85 (SD = .69), both indicating satisfactory fidelity.

Control Condition

Mothers randomized into the control condition also received individual sessions (2 total performed by research staff at baseline and exit) and 10 weekly mailings of the Mom Power curriculum content. The goal of these sessions was the same of the intervention and control conditions; indeed, at baseline the family had not yet been randomized and the goal was to engage the family, build rapport, and to collect assessment data. Weekly control group mailings included a pre-stamped post card for the mother to send back indicating that the week's material had been read; written material provided was written at a 7th grade level. For each postcard returned the participant was compensated $5. For sending back at least 7 of 10 post cards the participant was compensated an additional $15. Thus, this study employed a stringent control, as both groups received the same remuneration, and both groups had access to parallel content with regards to the parenting curriculum, albeit delivered in different formats.

Measures

Demographics

Mothers self-reported on age, annual household income, education level, marital status, and race/ethnicity; in addition, they reported on age and gender of all children participating. Participating mothers with more than one child in the age range (0 to 5 years) were asked to indicate one target child and answer all parenting measures specific to the index child.

Baseline Characteristics

Trauma exposure. Childhood maltreatment and adult life stress/trauma exposure were assessed using a modified version of the Life Stressor Checklist [76]. Mental health. Depression symptoms were assessed using the Postpartum Depression Screening Scale (PPDS) [77]. PTSD symptoms were assessed using The National Women's Study PTSD Module (NWS-PTSD) [78].

Maternal representations of the child

Each mother participated in a slightly abbreviated version of the Working Model of the Child Interview [21, 23]; questions regarding experiences of pregnancy and early development were omitted. This version of the WMCI has been demonstrated to be reliable and valid among samples that are diverse in terms of sociodemographic characteristics and mental health status [24, 79]. For the present study each WMCI was coded to identify both the standard primary typology classification as well as a dimensional rating of the mothers' capacity for reflective functioning assessed via a Parenting Reflectivity scale.

As described in Table 1, each narrative was assigned to one of the three standard WMCI typologies: balanced, Disengaged, or Distorted [23]. In addition, a previously validated Parenting Reflectivity scale was used in the current study [79]. High parenting reflectivity scores indicate significant reflective reasoning in the interview, for example, acknowledging and tolerating complex feelings about the parenting role, and/or searching for the mental meaning that motivates parents' own and their child's behavior. Low scores indicate that the parent very rarely acknowledged feelings or mental states and generally did not acknowledge the influence of psychological processes on their own or others behavior.

Table 1. Baseline differences between Treatment and Control condition for paired subsample (N = 75).

| Domain | MP Intervention (n = 42) | Control (n = 33) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Mean (SD) or n (%) | Mean (SD) or n (%) | t or X2 | p-value | |

| Demographics | ||||

| Mother's Age (years) | 24.05 (8.28) | 24.48 (5.71) | -.26 | .80 |

| Child's Age (months) | 15.07 (12.22) | 21.50 (19.26) | -1.62 | .11 |

| Education | ||||

| Less than H.S. | 19 (45.2%) | 7 (21.2%) | ||

| H.S. or GED | 5 (11.9%) | |||

| Some College | 11 (26.2%) | |||

| AA Degree | 1 (2.4%) | |||

| Vocational/Technical Degree | 3 (7.1%) | |||

| Bachelors Degree | 0 (0%) | |||

| Masters Degree | 3 (7.1%) | |||

| Income | ||||

| Less than 15k/year | 29 (69.0%) | 18 (54.5%) | ||

| $15,000-$29,999 | 6 (14.3%) | |||

| $30,000-$49,999 | 3 (7.1%) | |||

| $50,000- $74,999 | 1 (2.4%) | |||

| $75,000-$99,999 | 0 (0%) | |||

| More than $100,000 | 3 (7.1%) | |||

| Marital Status | ||||

| Single | 26 (61.9%) | 20 (60.6%) | .01 | .91 |

| Partnered | 16 (38.1%) | 13 (39.4%) | ||

| Race | ||||

| Caucasian | 13 (31.0%) | 10 (30.3%) | ||

| African American | 26 (61.9%) | |||

| Latino | 0 (0%) | |||

| Native American | 0 (0%) | |||

| Two or more races | 2 (4.8%) | |||

| Other | 1 (2.4%) | |||

|

| ||||

| Trauma Exposure | ||||

| Interpersonal Trauma | 27 (64.3%) | 17 (51.5%) | 1.24 | .27 |

|

| ||||

| Mental Health | ||||

| Baseline PTSD symptoms | 6.93 (4.44) | 4.88 (4.28) | 2.02 | .05* |

| Baseline MDD symptoms | 80.98 (29.76) | 76.59 (28.93) | .64 | .52 |

|

| ||||

| Connection to Care | ||||

| Receiving mental health services at baseline | 14 (33.3%) | 7 (21.2%) | 1.35 | .25 |

p < .05

Coders of the transcripts were trained to reliability in coding by the first author, a trained and reliable WMCI coder, and were blind to condition. For the present study 41% (n = 31) of the transcripts were double coded in order to assess inter-rater reliability. In order to monitor potential rater drift transcripts were assigned intermittently for double coding across the coding period; raters were blind to the double-coded set. Exact agreement for WMCI typology classification was achieved for 87% of the reliability transcripts (kappa = .81, p < .01), indicating substantial agreement; disagreements were resolved by consensus. Reliability for the WMCI Parenting Reflectivity scale was established via intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) between the two independent raters and indicated good reliability (ICC = .71).

Data Analysis

Initial analyses examined potential differences in attrition based on baseline characteristics including demographics, trauma, maternal mental health, and where available, baseline WMCI scores using t-tests and chi-square analyses. Next, independent samples t-tests and chi-squared tests were used for preliminary analyses between groups at baseline. Given the small sample size and limited statistical power, pre-post analyses were conducted separately within each condition. Thus, to examine the effect of the intervention on change in typology, a McNemar-Bowker test was used. Second, a McNemar test was used to determine if Mom Power was successful in increasing balanced representations among mothers in the treatment group. Finally, within-group paired t-tests were conducted to assess change in the Parenting Reflectivity scale. Hypotheses were that MP treatment would increase the percentage of parents' typologies classified as “balanced” and improve parents representational functioning; given the directional a priori hypotheses one-tailed tests of significance were employed.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Analysis of study variables at baseline indicated that baseline characteristics (demographics, mental health, trauma, WMCI classification) were unrelated to study attrition. Subsequent analyses included only the subset of n=75 who had complete pre and post WMCI data. Descriptive data regarding baseline characteristics for the sample are provided in Table 1. Frequencies of categorical classifications of typology at pre- and post-test are found in Table 2. Typology category and rates of balanced representations did not differ between groups at baseline, χ2(2, n= 75) =.98, p = .61 and χ2(2, n= 75) =.20, p = .80, respectively. Approximately two-thirds of the mothers in both the Control and Intervention groups had non-balanced representation classifications at the pre-assessment. Descriptive statistics of Parenting Reflectivity are found in Table 3. There were no differences between groups on Parenting Reflectivity at baseline (p = .73). Treatment and condition groups did differ on symptoms of PTSD and educational attainment risk status (receiving less than high school degree) but did not differ on other baseline demographic characteristics (age, race, income) including depression and trauma exposure (see Table 1).

Table 2.

| Treatment (n = 42) | Control (n = 33) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| % (n) | % (n) | |||

|

|

||||

| Pre Typology | Post Typology | Pre Typology | Post Typology | |

|

|

||||

| Balanced | 28.6% (12) | 52.4% (22)* | 33.3% (11) | 30.3% (10) |

| Distorted | 33.3% (14) | 31.0% (13)* | 39.4% (13) | 33.3% (11) |

| Disengaged | 38.1% (16) | 16.7% (7)* | 27.3% (9) | 36.4% (12) |

Note:

p < .05 change in proportion of typology pre to post

Table 3.

Results of paired t-tests reflecting changes pre-to-post-assessment on the Reflective Parenting scale, separately for the Treatment and Control group.

| Treatment | Control | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| M (SD) | p-value | Cohen's d | M (SD) | p-value | Cohen's d | |||

|

|

||||||||

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |||||

| Reflective parenting | 2.62 (.91) | 2.88 (.86) | .039* | .296 | 2.70 (1.01) | 2.76 (.87) | .66 | -.064 |

p<.05

Treatment effects

The proportion of each typology (balanced, Disengaged, or Distorted) significantly changed pre to post in the treatment condition, X2M(3, n = 42) = 10.20, p = .02, φ = .49, but not in the control condition, X2M(3, n = 33) = 1.20, p = .75. To determine if typology change represented an increase in balanced representations, a two-way contingency table analysis was conducted between balanced and non-balanced representations in each group across time. As seen in Table 3, within the treatment group, the number of women with balanced representations increased from 12 to 22, while the number of women with non-balanced representations decreased from 30 to 20. The improvement in balance was significant in the treatment group, X2M(1, n= 42), exact p = .05, but the control condition demonstrated no significant change, X2M(1, n= 33), exact p = 1.

Regarding Parenting Reflectivity, the results of paired t-tests separated by group are found in Table 3. Average scores for mothers in the treatment group significantly increased between pre- and posttest on Parenting Reflectivity. There was no significant change in the control condition.

Discussion

The 13-week Mom Power curriculum aims to strengthen the parent-child relationship through delivery of an integrated parent- and child-focused curriculum that supports positive parenting, parent mental health, and parent-child interaction. Results of the current randomized controlled trial indicate that participation in the Mom Power program was associated with improvements in a key indicator of the security of the parent-child relationship, specifically mothers' representations of their children. The significance of this finding is underscored by the relatively conservative test of this intervention, in that mothers in the control condition were each provided with written materials that conveyed all of the core information provided in the multifamily group context, thus indicating that the multifamily group with corresponding in-person delivery of components was critical for achieving positive program impact.

Enhancing parenting representations represents an important target for intervention given the hypothesized role of representations in both shaping parents' interpretations of infant behavior and in guiding parents' behavioral responses to the child [23, 24]. Yet prior studies of parenting interventions that have tested impact on qualities of parental representation, including indicators of reflective functioning, have largely been limited by lack of a control group (e.g., [11, 60, 61] and/or reliance on less well validated parental representation interviews (e.g., [60]. In addition, to our knowledge there are no previously published reports of attachment-focused RCTs indicating changes in the overall quality of the parents' representational classification, that is, a move to balanced (secure type) from non-balanced (insecure type) associated with a parenting intervention.

In the current study, rates of balanced representations significantly improved from pre- to post-group for the intervention condition, with no significant change evident in the control condition. Improvement in typology scores for the treatment group was largely due to changes from disengaged to balanced status pre- to post-intervention. Disengaged narratives are typically characterized by a sense of emotional distancing; for example, parents whose narratives are classified as disengaged often have less to say about the child and about their feelings as their child's parent, less acceptance of the child's needs and greater resentment of the demands of the parenting role, and convey greater indifference towards the child's emotions or experiences. The fact that changes were most evident for this disengaged group suggests that the program was most effective in enhancing parental awareness of and responsiveness to child emotional needs, and in mitigating a tendency towards rejection or resentment regarding those needs. This was underscored by a significant change in the treatment group's reflective parenting scores. This increase in reflective functioning might therefore be a mechanism by which the intervention exerts its effects on maternal representations. Importantly, this change in typology of representations implies objective assessment of clinically meaningful change.

The Mom Power intervention is unique in that is highly manualized, can be delivered in a brief period (13 sessions), and has been developed with extensive input from the population served. While parenting is a key outcome, the intervention also aims to enhance self-care skills, encourage social support, and connect families to resources, thereby increasing range of established protective factors.

Limitations of this study include the relatively small sample size and study attrition, though the sample size reported here is equivalent to or larger than a number of other published studies investigating the impact of an attachment based intervention on reflective functioning and mental representations [60, 61, 80]. Attrition is expectable given the high-risk nature of the sample, and analyses suggest that this did not bias the sample. Finally, this study did not employ a newer classification system for the WMCI that has recently been developed to assess the “Disorganized” category of representation [81]. Given the clear clinical relevance of Disorganized patterns of attachment, it is possible that inclusion of this category would contribute additional information regarding patterns of change and program impact, and this would seem to be a fruitful direction for subsequent investigation.

Despite the limitations, there were a number of strengths to the current study. First, this study employed an RCT design in the context of community-based implementation of an integrated mental health and parenting curriculum for high risk families. Second, this study represents a fairly rigorous test of the impact of the intervention in that the “attentional control” group was provided with written materials that conveyed most of the core content of the intervention including all of the key parenting guidance materials and metaphors as well as self-care activities as delivered in the group setting.

Taken together, current results support the efficacy of this brief, attachment-based trauma-informed multifamily group intervention for improving key indicators of objectively-assessed parenting among high-risk mothers and their young children. Future research should examine whether this strengthening of parental representations and capacity for reflective functioning ultimately leads to improved child social-emotional and attachment outcomes.

Summary

A key mechanism of possible risk transmission between maternal risk (e.g., trauma history, psychopathology) and child outcomes are the mother's representations, that is, her perceptions, expectations, and subjective experiences of parenting and of her child. The current study examined the effects of an attachment based, trauma informed parenting intervention, the Mom Power program (Muzik et al., 2015), in optimizing maternal representations of high-risk mothers utilizing a randomized, controlled trial design (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01554215). High-risk mothers were recruited from low-income community locations, primary care clinics, and community mental health centers, and randomized to either the Mom Power Intervention (n = 42) or a weekly mailing control condition (n = 33) in a parallel design. Maternal representations were assessed before and after the intervention using the Working Model of the Child Interview. Within group analyses showed that the proportion of women with Balanced (secure type) representations increased in the Mom Power group while there was no change in the control group. Average Parenting Reflectivity for mothers in the treatment group significantly increased between pre- and posttest. There was no significant change in the control condition. Results from this randomized, controlled trial indicate that participation in the Mom Power program was associated with improvements in a key indicator of the security of the parent-child relationship: mothers' representations of their children. The increase in reflective functioning might be a mechanism by which the intervention exerts its effects on maternal representations.

Acknowledgments

The research presented was supported through funds from the State of Michigan, Department of Community Health, (PI: Muzik, F023865-2009 and F029321-2010); Michigan Institute for Clinical & Health Research (MICHR) (PI: Rosenblum, UL1RR024986-2010), and the Robert Wood Johnson Health & Society Scholars Program (PI: Muzik; N012918-2010). We thank the community agencies (i.e., Starfish Family Services, Inkster, Michigan; The Guidance Center, Southgate, Michigan) and their clinicians serving the families for participating in this trial. We thank the families who participated in this project. We acknowledge the valuable efforts of the Mom Power project staff in program development, implementation and data collection.

Footnotes

Disclosures of Conflicts of Interest: none

References

- 1.Goodman SH, Gotlib IH. Risk for psychopathology in the children of depressed mothers: A developmental model for understanding mechanisms of transmission. Psychological Review. 1999;106:458–490. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.106.3.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halligan SL, Murray L, Martins C, Cooper PJ. Maternal depression and psychiatric outcomes in adolescent offspring: a 13-year longitudinal study. Journal of affective disorders. 2007;97:145–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martins C, Gaffan EA. Effects of Early Maternal Depression on Patterns of Infant-Mother Attachment: A Meta-analytic Investigation. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2000;41:737–746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tough SC, et al. Maternal mental health predicts risk of developmental problems at 3 years of age: follow up of a community based trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2008;8:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-8-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benoit D, Parker KC, Zeanah CH. Mothers' representations of their infants assessed prenatally: Stability and association with infants' attachment classifications. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1997;38:307–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sroufe A, Egeland B, Carlson E, Collins W. The Development of the Person. Guilford Press; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lyons-Ruth K, Block D. The disturbed caregiving system: Relations among childhood trauma, maternal caregiving, and infant affect and attachment. Infant Mental Health Journal. 1996;17:257–275. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schechter DS, et al. Maternal mental representations of the child in an inner-city clinical sample: Violence-related posttraumatic stress and reflective functioning. Attachment & human development. 2005;7:313–331. doi: 10.1080/14616730500246011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muzik M, Rosenblum K, Schuster M. Mom Power Curriculum. University of Michigan; 2010. Unpublished Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muzik M, Rosenblum K, Schuster M, Kohler E, Alfafara E. A Mental Health and Parenting Intervention for Adolescent and Young Adult Mothers and their Infants. J Depress Anxiety. 2016;5:2167–1044.1000233. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muzik M, et al. Mom Power: preliminary outcomes of a group intervention to improve mental health and parenting among high-risk mothers. Archives of Women's Mental Health. 2015;18:507–521. doi: 10.1007/s00737-014-0490-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bowlby J. Attachment. Basic Books; New York: 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 13.van IJzendoorn MH, Juffer F, Duyvesteyn MGC. Breaking the Intergenerational Cycle of Insecure Attachment: A Review of the Effects on Attachment-Based Interventions on Maternal Sensitivity and Infant Security. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1995;36:225–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1995.tb01822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raval V, et al. Maternal attachment, maternal responsiveness and infant attachment. Infant Behavior and Development. 2001;24:281–304. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bretherton I, Munholland K. Internal Working Models in Attachment Relationships: Elaborating a central construct in Attachment Theory. In: Cassidy IJ, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of Attachment: Theory, Research and Clinical Applications. New York: The Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 102–127. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bretherton I, Biringen Z, Ridgeway D, Maslin C, et al. Attachment: The parental perspective. Infant Mental Health Journal. 1989;10:203–221. [Google Scholar]

- 17.George C, Solomon J. Representational models of relationships: Links between caregiving and attachment. Infant Mental Health Journal. 1996;17:198–216. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Slade A, Aber J, Berger B, Bresgi I, Kaplan M. The Parent Development Interview-Revised. Yale Child Study Center; 2002. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zeanah CH, et al. Representations of attachment in mothers and their one-year-old infants. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1993;32:278–286. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199303000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Slade A, Belsky J, Aber JL, Phelps JL. Mothers' representations of their relationships with their toddlers: links to adult attachment and observed mothering. Developmental psychology. 1999;35:611. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.3.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosenblum KL, McDonough S, Muzik M, Miller A, Sameroff A. Maternal Representations of the Infant: Associations with Infant Response to the Still Face. Child Development. 2002;73:999–1015. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vreeswijk CM, Maas AJ, van Bakel HJ. Parental representations: A systematic review of the working model of the child interview. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2012;33:314–328. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zeanah CH, Benoit D. Clinical applications of a parent perception interview in infant mental health. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosenblum KL, Dayton C, McDonough S. Communicating Feelings: Links Between Mothers' Representations of Their Infants, Parenting, and Infant Emotional Development Parenting Representations. Cambridge University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Korja R, et al. Relations between maternal attachment representations and the quality of mother-infant interaction in preterm and full-term infants. Infant Behavior and Development. 2010;33:330–336. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zeanah CH, Benoit D, Hirshberg L, Barton M, Regan C. Mothers' representations of their infants are concordant with infant attachment classifications. Developmental Issues in Psychiatry and Psychology. 1994;1:9–18. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sokolowski MS, Hans SL, Bernstein VJ, Cox SM. Mothers' representations of their infants and parenting behavior: Associations with personal and social-contextual variables in a high-risk sample. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2007;28:344–365. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Borghini A, et al. Mother's attachment representations of their premature infant at 6 and 18 months after birth. Infant mental health journal. 2006;27:494–508. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dayton CJ, Levendosky AA, Davidson WS, Bogat GA. The child as held in the mind of the mother: The influence of prenatal maternal representations on parenting behaviors. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2010;31:220–241. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schechter DS, et al. Distorted maternal mental representations and atypical behavior in a clinical sample of violence-exposed mothers and their toddlers. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation. 2008;9:123–147. doi: 10.1080/15299730802045666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gavin NI, et al. Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2005;106:1071–1083. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000183597.31630.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seng JS. Prevalence, Trauma History, and Risk for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Among Nulliparous Women in Maternity Care. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2009;114:839–847. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181b8f8a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sexton MB, Hamilton L, McGinnis EW, Rosenblum KL, Muzik M. The roles of resilience and childhood trauma history: Main and moderating effects on postpartum maternal mental health and functioning. Journal of affective disorders. 2015;174:562–568. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.12.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oh W, et al. Comorbid trajectories of postpartum depression and PTSD among mothers with childhood trauma history: Course, predictors, processes and child adjustment. Journal of affective disorders. 2016;200:133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.04.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kendall-Tackett KA. Violence against women and the perinatal period: The impact of lifetime violence and abuse on pregnancy, postpartum, and breastfeeding. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2007;8:344–353. doi: 10.1177/1524838007304406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Conroy S, Marks MN, Schacht R, Davies HA, Moran P. The impact of maternal depression and personality disorder on early infant care. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology. 2010;45:285–292. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0070-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feldman R, et al. Maternal depression and anxiety across the postpartum year and infant social engagement, fear regulation, and stress reactivity. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48:919–927. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181b21651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Muzik M, et al. Perspectives on trauma-informed care from mothers with a history of childhood maltreatment: A qualitative study. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2013;37:1215–1224. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Ee E, Kleber RJ, Jongmans MJ. Relational patterns between caregivers with PTSD and their nonexposed children: A review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2016;17:186–203. doi: 10.1177/1524838015584355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lovejoy MC, Graczyk PA, O'Hare E, Neuman G. Maternal depression and parenting behavior: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20:561–592. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morelen D, Menke R, Rosenblum KL, Beeghly M, Muzik M. Understanding bidirectional mother-infant affective displays across contexts: effects of maternal maltreatment history and postpartum depression and PTSD symptoms. Psychopathology. 2016;49 doi: 10.1159/000448376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Muzik M, et al. Psychopathology and parenting: an examination of perceived and observed parenting in mothers with depression and PTSD. Journal of affective disorders. 2017;207:242–250. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.08.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martinez-Torteya C, et al. Maternal parenting predicts infant biobehavioral regulation among women with a history of childhood maltreatment. Development and psychopathology. 2014;26:379–392. doi: 10.1017/S0954579414000017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goodman SH, Garber J. Evidence-Based Interventions for Depressed Mothers and Their Young Children. Child Development. 2017;88:368–377. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Field T, Healy BT, Goldstein S, Guthertz M. Behavior-state matching and synchrony in mother-infant interactions of nondepressed versus depressed dyads. Developmental Psychology. 1990;26:7–14. [Google Scholar]

- 46.NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. Affect dysregulation in the mother-child relationship in the toddler years: Antecedents and consequences. Development and psychopathology. 2004;16:43–68. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404044402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goodman SH, et al. Maternal depression and child psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical child and family psychology review. 2011;14:1–27. doi: 10.1007/s10567-010-0080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Murray L, et al. The socioemotional development of 5-year-old children of postnatally depressed mothers. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1999;40:1259–1271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Beck CT. A meta-analysis of the relationship between postpartum depression and infant temperament. Nursing research. 1996;45:225–230. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199607000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Elgar FJ, McGrath PJ, Waschbusch DA, Stewart SH, Curtis LJ. Mutual influences on maternal depression and child adjustment problems. Clinical psychology review. 2004;24:441–459. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Muzik M, Marcus SM, Flynn HA. Psychotherapeutic treatment options for perinatal depression: emphasis on maternal-infant dyadic outcomes. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2009;70:1318–1319. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09com05451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Forman DR, et al. Effective treatment for postpartum depression is not sufficient to improve the developing mother-child relationship. Development and psychopathology. 2007;19:585–602. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407070289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nylen KJ, Moran TE, Franklin CL, O'Hara MW. Maternal depression: A review of relevant treatment approaches for mothers and infants. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2006;27:327–343. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reyno SM, McGrath PJ. Predictors of parent training efficacy for child externalizing behavior problems–a meta-analytic review. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47:99–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Murray L, Cooper PJ, Wilson A, Romaniuk H. Controlled trial of the short- and long-term effect of psychological treatment of post-partum depression. 2. Impact on the mother--child relationship and child outcome. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;182:420–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Main M, Kaplan N, Cassidy J. Security in infancy, childhood, and adulthood: A move to the level of representation. Monographs of the society for research in child development. 1985:66–104. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stacks AM, Oshio T. Disorganized attachment and social skills as indicators of Head Start children's school readiness skills. Attachment & human development. 2009;11:143–164. doi: 10.1080/14616730802625250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cassidy J, Woodhouse SS, Sherman LJ, Stupica B, Lejuez C. Enhancing infant attachment security: An examination of treatment efficacy and differential susceptibility. Development and psychopathology. 2011;23:131–148. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lieberman AF, Van Horn P, Ippen CG. Toward evidence-based treatment: Child-parent psychotherapy with preschoolers exposed to marital violence. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44:1241–1248. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000181047.59702.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huber A, McMahon CA, Sweller N. Efficacy of the 20-week Circle of Security Intervention: Changes in Caregiver Reflective Functioning, Representations, and Child Attachment in an Australian Clinical Sample. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2015;36:556–574. doi: 10.1002/imhj.21540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schechter DS, et al. Traumatized mothers can change their minds about their toddlers: Understanding how a novel use of videofeedback supports positive change of maternal attributions. Infant mental health journal. 2006;27:429. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Suchman NE, Decoste C, Mcmahon TJ, Rounsaville B, Mayes L. The mothers and toddlers program, an attachment-based parenting intervention for substance-using women: Results at 6-week follow-up in a randomized clinical pilot. Infant mental health journal. 2011;32:427–449. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sealy J, Glovinsky IP. Strengthening the Reflective Functioning Capacities of Parents Who Have a Child With a Neurodevelopmental Disability Through a Brief, Relationship-Focused Intervention. Infant mental health journal. 2016 doi: 10.1002/imhj.21557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fonagy P, Sleed M, Baradon T. Randomized Controlled Trial of Parent-Infant Psychotherapy for Parents With Mental Health Problems and Young Infants. Infant mental health journal. 2016 doi: 10.1002/imhj.21553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cloitre M, et al. A developmental approach to complex PTSD: Childhood and adult cumulative trauma as predictors of symptom complexity. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2009;22:399–408. doi: 10.1002/jts.20444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Herman J. Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence - from Domestic Abuse to Political Terror. Basic Books; New York: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Erickson M, Egeland B. The STEEP program: Linking theory and research to practice. Zero to Three. 1999;20:11–16. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lowell DI, Carter AS, Godoy L, Paulicin B, Briggs-Gowan MJ. A randomized controlled trial of Child FIRST: a comprehensive home-based intervention translating research into early childhood practice. Child Dev. 2011;82:193–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Olds DL. The nurse–family partnership: An evidence-based preventive intervention. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2006;27:5–25. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Powell B, Cooper G, Hoffman K, Marvin B. The circle of security intervention: Enhancing attachment in early parent-child relationships. Guilford Publications; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lieberman AF, Van Horn P. Assessment and Treatment of Young Children Exposed to Traumatic Events 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 72.Muzik M, et al. Predictors of Treatment Engagement to the Parenting Intervention Mom Power Among Caucasian and African American Mothers. Journal of Social Service Research. 2014:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Muzik M, Kirk R, Alfafara E, Jonika J, Waddell R. Teenage mothers of black and minority ethnic origin want access to a range of mental and physical health support: a participatory research approach. Health Expectations. 2015 doi: 10.1111/hex.12364. n/a-n/a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Allocation concealment in randomised trials: defending against deciphering. The Lancet. 2002;359:614–618. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07750-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wei L, Lachin JM. Properties of the urn randomization in clinical trials. Controlled Clinical Trials. 1988;9:345–364. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(88)90048-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wolfe J, Kimerling R. Gender issues in the assessment of posttraumatic stress disorder. In: Wilson JP, Keane TM, editors. Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD. Guilford Press; New York, NY US: 1997. pp. 192–238. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Beck CT, Gable RK. Further validation of the Postpartum Depression Screening Scale. Nursing Research. 2001;50:155–164. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200105000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Saunders BE, Best CL. The National Women's Study PTSD Module. Medical University of Souh Carolina; Charleston, SC: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rosenblum KL, McDonough SC, Sameroff AJ, Muzik M. Reflection in thought and action: Maternal parenting reflectivity predicts mind-minded comments and interactive behavior. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2008;29:362–376. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Suchman NE, DeCoste C, Leigh D, Borelli J. Reflective functioning in mothers with drug use disorders: Implications for dyadic interactions with infants and toddlers. Attachment & human development. 2010;12:567–585. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2010.501988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Niccols A, Smith A, Benoit D. The working Model of the Child Interview: Stability of the disrupted classification in a community intervention sample. Infant mental health journal. 2015;36:388–398. doi: 10.1002/imhj.21522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]