Abstract

Background

In 2016, we detected an outbreak of group A Streptococcus (GAS) invasive infections among the estimated 1000 persons experiencing homelessness (PEH) in Anchorage, Alaska. We characterized the outbreak and implemented a mass antibiotic intervention at homeless service facilities.

Methods

We identified cases through the Alaska GAS laboratory-based surveillance system. We conducted emm-typing, antimicrobial susceptibility testing, and whole genome sequencing (WGS) on all invasive isolates and compared medical record data of patients infected with emm26.3 and other emm types. In February 2017, we offered PEH at six facilities in Anchorage a single dose of 1 gram of azithromycin. We collected oropharyngeal and non-intact skin swabs on a subset of participants concurrent with the intervention and 4 weeks afterward.

Results

From July 2016–April 2017, we detected 42 invasive emm26.3 cases in Anchorage, 35 of which were in PEH. The emm26.3 isolates differed on average by only 2 single nucleotide polymorphisms. Compared to other emm types, infection with emm26.3 was associated with cellulitis (odds ratio [OR] 2.5, p=0.04) and necrotizing fasciitis (OR 4.4, p=0.02). We dispensed antibiotics to 391 PEH. Colonization with emm26.3 decreased from 4% of 277 at baseline to 1% of 287 at follow-up (p=0.05). Invasive GAS incidence decreased from 1.5 cases per 1000 PEH/week in the 6 weeks prior to the intervention to 0.2 cases per 1000 PEH/week in the 6 weeks after (p=0.01).

Conclusions

In an invasive GAS outbreak in PEH in Anchorage, mass antibiotic administration was temporally associated with reduced invasive disease cases and colonization prevalence.

Keywords: Group A Streptococcus, Outbreak, Homeless, Mass antibiotic administration

Introduction

Manifestations of invasive group A Streptococcus (GAS) infection range from cellulitis and pneumonia to necrotizing fasciitis and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome. GAS results in a large burden of invasive disease in the United States (U.S.) [1, 2]. In 2015, over 15,000 cases of invasive disease and over 1,600 deaths were estimated to occur nationally [3]. In Alaska, incidence rate of invasive GAS disease in 2015 was 12.3 cases per 100,000 persons, over twice that of the rest of the United States [4].

GAS strains can be subdivided into over 240 different surface M protein gene (emm) types, which are grouped into a smaller number of emm region patterns and structurally related emm gene clusters [5–7]. Although only 25 emm types contribute to the majority of disease [5, 8], rare types of GAS for a given region can cause increases in invasive disease incidence, potentially due to low population immunity or to core genomic recombination in a strain [9–14].

Although invasive GAS has been reported among persons experiencing homelessness (PEH) in Canada and Europe [10, 15–17], homelessness has not been a widely reported risk factor for invasive GAS illness in the United States. As a result, U.S. recommendations do not exist for controlling invasive GAS outbreaks in community settings such as homeless shelters.

In July 2016, we identified an outbreak of GAS invasive disease among PEH in Anchorage, Alaska. Approximately 1,000 PEH live in Anchorage, the majority of whom are considered to be “sheltered” in two primary shelters or housed in supportive housing units [18]. We describe here the results of the outbreak investigation and control measures.

Methods

Surveillance and Outbreak Detection

In Alaska, invasive GAS infection is reportable to the Alaska Division of Public Health. Since 2000, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s Arctic Investigations Program (AIP) has also conducted statewide, laboratory- and population-based surveillance for GAS [19]. Laboratories send sterile site GAS isolates to AIP for confirmatory testing, antibiotic susceptibility testing, and molecular typing. Cases of invasive GAS infection are defined as illnesses with GAS isolated from a normally sterile body site, or isolation of GAS from a nonsterile site in persons with necrotizing fasciitis or streptococcal toxic shock syndrome.

An outbreak was declared when case counts of an emm-type new to the region were higher than expected within a particular community. Outbreak-associated cases were defined as an invasive GAS case typed as emm26.3. Cases were included if patients were identified at an Anchorage hospital, even if their place of residence was not Anchorage. Cases identified in hospitals outside of Anchorage were described epidemiologically, but were not considered part of the outbreak. Prior to the outbreak investigation, we consulted with Human Subjects advisors at the CDC National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases and National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases who determined this to be non-research public health practice and formal IRB review was not required (#102516; #2017 6692).

Clinical characterization of GAS invasive disease

We reviewed medical records of all persons with emm26.3 invasive GAS infection and persons with non-emm26.3 invasive disease who were admitted to a hospital within the same month as an outbreak-associated case in Anchorage hospitals from July 1, 2016 to May 1, 2017. We used a standard chart abstraction form to collect case demographic and clinical data.

Outbreak Response

Between October 2016 and January 2017, we conducted contact-tracing and provided GAS infection information to PEH, staff, and clinic volunteers. Because case counts remained high, in February 2017, we carried out a mass antibiotic administration in sites frequented by PEH living in Anchorage. Sites included two shelters, two soup kitchens, and two supportive housing units. We considered safety, effectiveness, cost, route of delivery, and dosing when selecting the antibiotic. We chose a single dose oral regimen to maximize adherence and acceptability. Based on previous GAS colonization and treatment studies, we offered a single dose of 1g of azithromycin [20–22].

Between February 13th and 17th, 2017, teams of clinical providers and public health staff visited the six homeless services sites. The team provided clients information about the outbreak and the risks and benefits of taking azithromycin. Participation was voluntary. Staff and volunteers at the homeless service facilities were also offered antibiotics. Clinicians evaluated consenting clients for potential contraindications (e.g., a macrolide allergy, history of heart disease, or liver disease) and drug-drug interactions (i.e., risk category C, D, or X)[23]. Consenting participants swallowed the azithromycin with water under the observation of a clinician.

Outbreak Response Evaluation

We evaluated the effectiveness of the outbreak response by comparing emm26.3 colonization prevalence and invasive disease incidence before and after the antibiotic intervention. Clients were offered an opportunity to participate in a baseline colonization survey during the antibiotic intervention. For consenting clients, clinicians obtained oropharyngeal (OP) swabs. Clinicians also swabbed areas of non-intact skin (e.g., abrasions, insect bites, dermatitis) in an accessible area (e.g., arms or legs), if available. This process was repeated 4 weeks later (March 13–17, 2017). The AIP laboratory cultured the specimens for GAS and conducted molecular subtyping for positive cultures, as described below.

Laboratory methods

Laboratory staff confirmed GAS isolates by β-hemolysis on sheep blood agar, Lancefield antigen grouping using a commercially available agglutination test kit (Phadebact Strep A kit), and the pyrrolidonyl-arylamidase test (PYR 50 test kit; Remel Inc., Lenexa, KS). Colonization isolates were plated onto selective agar (Remel, Lenexa, KS), subcultured onto sheep blood agar, and processed as above. Staff tested all invasive disease isolates for antimicrobial susceptibility to penicillin, erythromycin, tetracycline, levofloxacin, cefotaxime, and clindamycin according to standard methods [24]. Emm-typing was conducted weekly by AIP according to CDC protocols [25, 26]. Staff performed sequence analysis by a BLAST search on the CDC streptococcal emm sequence database to designate sequence type [27].

Whole genome sequencing (WGS)

Emm26.3 GAS invasive disease isolates from Alaska, including those identified outside of Anchorage, were sent to CDC’s Streptococcus Laboratory for whole genome sequence analysis. Paired-end, 250-bp WGS was performed using a MiSeq platform. The short reads were assembled using VelvetOptimiser2.2.5 and single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) were called using kSNP3.0. Reads were also analyzed by an in-house bioinformatics pipeline to detect gene features, including resistance determinants [28]. We reconstructed the phylogeny based on shared SNPs using RAxML (version 8.2.9). Emm subtypes were obtained based upon a database of 180 bp defined sequences maintained at CDC [29].

Statistical analyses

We calculated frequencies of clinical and demographic characteristics of patients with emm26.3 infection. We compared these characteristics to those of patients with non-emm26.3 invasive GAS infection using Fischer’s exact tests and general linear regression. Clusters of invasive cases based on whole genome sequencing were also compared using exact tests and linear regression.

We linked the datasets from the pre- and post-intervention colonization surveys and used binomial general estimating equations, clustered by individual, to estimate the difference in colonization prevalence between the two time points. Shelter staff and volunteers were not included in the analysis. We calculated the incidence rate of invasive emm26.3 GAS infection using an estimated population of 1000 PEH in Anchorage and compared the incidence rates before and after the intervention using Poisson distribution exact tests [18].

Results

Surveillance and outbreak detection

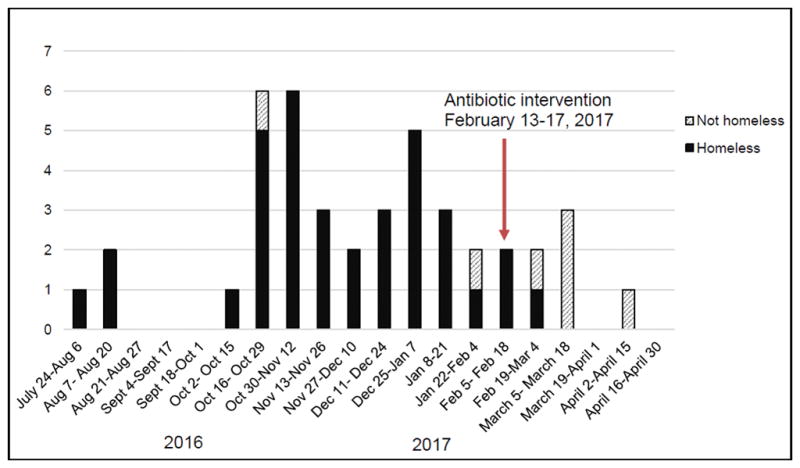

Data from Alaska’s GAS surveillance revealed the first cases of invasive emm26.3 infection occurred in villages surrounding Fairbanks in the spring of 2016. By August 2016, 11 cases had occurred around Fairbanks, and an investigation was initiated, but no epidemiologic connections were identified. Between July and August, three cases were detected in Anchorage; all three were in PEH. Beginning in October, 2016, the number of invasive GAS cases caused by emm26.3 among PEH in Anchorage rapidly increased. By May 1, 2017, 42 cases of emm26.3 GAS invasive disease had been identified in Anchorage (Figure 1). Of the cases in Anchorage, 35 were in PEH and seven were in people who were not homeless. Three of those who were not homeless had known links to PEH (such as volunteering or having homeless family members). Between February 2016 and May 2017, only two other cases of emm26.3 occurred in Alaska outside of Fairbanks area and Anchorage; neither patient was found to have traveled to either city or have links to PEH. The statewide epidemic curve is shown in the Supplemental Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Cases of emm26.3 group A Streptococcus invasive disease in Anchorage, Alaska, between July, 2016 and May, 2017

Clinical characterization of GAS infections and antimicrobial susceptibility testing

Among the 43 cases of invasive GAS infection caused by emm26.3 identified in three Anchorage hospitals from July 2016 to May 2017, one case occurred in a non-Anchorage resident. Among 47 non-emm26.3 cases identified in three Anchorage hospitals, seven occurred in patients who were not residents of Anchorage.

Among the 43 persons with invasive emm26.3 GAS infection, the mean age was 52 years, 28 (65%) were male, 32 (74%) were Alaska Native persons, 35 (81%) were experiencing homelessness at the time of illness onset, and 29 (67%) had a history of chronic alcohol use (Table 1). Non-emm26.3 invasive GAS infection (n=47) strain types included emm1, 4, 11, 12, 28, 49, 59, 81, and 91. Compared to patients with invasive GAS infection due to another emm type, emm26.3 patients were significantly older, and more often diagnosed with cellulitis and necrotizing fasciitis (Table 1). Three cases of emm26.3 resulted in death, compared to two cases among other emm-types (p=0.57). Emm26.3 invasive GAS isolates were susceptible to all antimicrobials tested.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of emm26.3 invasive disease cases compared to invasive disease cases caused by other emm types at Anchorage hospitals, July 2016– May 2017

| Characteristic | emm26.3 cases (N=43) | Non-emm26.3 cases (N=47) | P-valueb for difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SDa) | 52 (11) | 40 (22) | <0.01 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 28 (65%) | 30 (65%) | 1.00 |

| Homeless, n (%) | 35 (90%) | 4 (10%) | <0.01 |

| Diagnoses, n (%) | |||

| Cellulitis | 27 (63%) | 19 (40%) | 0.04 |

| Sepsis | 21 (49%) | 18 (38%) | 0.31 |

| Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome | 2 (4%) | 4 (9%) | 0.34 |

| Necrotizing fasciitis | 10 (23%) | 3 (6%) | 0.02 |

| Pneumonia | 5 (12%) | 1 (2%) | 0.07 |

| Pharyngitis | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 0.29 |

| Septic arthritis | 2 (5%) | 4 (8%) | 0.46 |

| Length (days) of hospital stayc, median (SD) | 14 (25) | 8.5 (61) | 0.02 |

| Admitted to ICU, n (%) | 16 (37%) | 14 (30%) | 0.45 |

| Required intubation, n (%) | 5 (12%) | 3 (6%) | 0.38 |

| Died, n (%) | 3 (7%) | 2 (4%) | 0.57 |

Abbreviations: ICU- Intensive Care Unit; SD- standard deviation

P values from Pearson’s chi square test or Fisher’s exact test if expected counts ≤5

Not including patients who died

Outbreak Response

During February 13–17, we held 8 intervention events at 6 homeless services sites. Healthcare provider teams evaluated 484 candidates for azithromycin therapy and dispensed a single dose to 391 persons (81%); 59 persons had contraindications to azithromycin and 34 others declined the antibiotic. Of those who received the antibiotic, the mean age was 48 years; 282 (72%) were men, 211 (54%) were Alaska Native persons, and 23 (6%) were facility staff or volunteers.

We recruited 277 participants in the baseline colonization survey. OP swabs were collected from all participants and non-intact skin swabs were collected from 71 (26%) participants. The mean age of participants was 52 years, 194 (70%) were men, and 147 (53%) were Alaska Native persons. GAS colonization (OP or non-intact skin) was identified in 27 (9%) participants; the most common type (12, 4%) was emm26.3. Emm26.3 colonization was identified in the OP of 9 (3%) participants and on non-intact skin of 4 participants (6% of those with non-intact skin swabs available). One individual was found to be colonized both in OP and on non-intact skin. All isolates of emm26.3 were pan-susceptible to antibiotics. Emm11 was the second most commonly identified strain; 12 of 13 emm11 isolates identified were resistant to azithromycin.

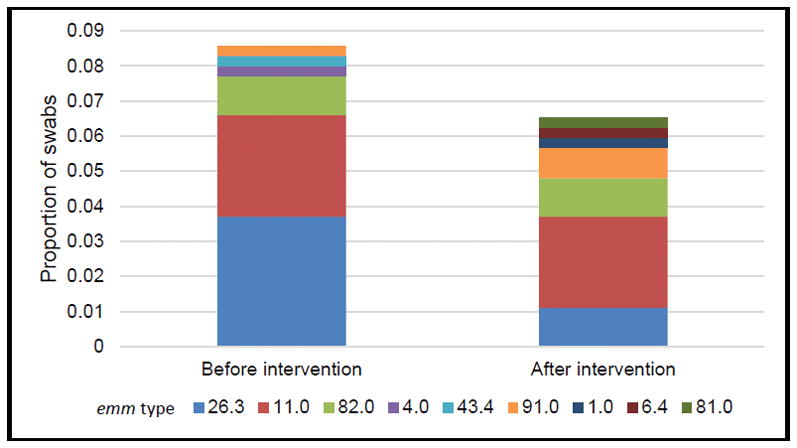

In March 2017, 4 weeks after the intervention, we recruited 287 participants into the follow-up survey, 95 (33%) of whom had also participated in the baseline survey. Swabs were collected from the OP of all participants from non-intact skin in 63 participants. The mean age of participants was 52 years; 195 (68%) were male, and 175 (61%) were Alaska Native persons. Nineteen (6%) participants were colonized with GAS, including 4 (1%) colonized with emm26.3 (P-value for change from baseline=0.05). Three (1%) participants had emm26.3 OP colonization and 1/63 (2%) had emm26.3 non-intact skin colonization. No one who was colonized with emm26.3 at follow-up had received the antibiotic intervention. At baseline and at follow-up, 5.1% and 5.0% of participants, respectively, were colonized with other emm types. Figure 2 shows the proportion of each emm type among all swabs (throat and non-intact skin) at baseline and follow-up. The follow-up emm26.3 colonization isolates were pan-susceptible to the antibiotics tested. Only emm11 isolates demonstrated antimicrobial resistance; all 10 were resistant to azithromycin.

Figure 2.

Distribution of emm types among all GAS colonization swabs (from non-intact skin and throat) among persons accessing homeless services before and four weeks after a single dose antibiotic intervention—Anchorage, Alaska 2017

The incidence of emm26.3 iGAS infection was 1.5 cases per 1000 PEH per week (nine cases) in the 6 weeks before the intervention, and 0.2 cases per 1000 PEH per week (one case) in the 6 weeks after the intervention (IRR 0.1, p=0.01). Although five additional cases occurred in persons who were not homeless, we did not include this group in the incidence estimates since they could not have received the intervention. Case counts among those who were not homeless decreased by the end of April, 2017 (Figure 1).

Whole genome sequencing

Sixty-five emm26.3 GAS isolates were available for WGS analysis (11 from Fairbanks and 54 from Anchorage); 14 were isolates from the colonization surveys. The emm26.3 isolates contained identical detailed WGS pipeline features and were multilocus sequence type 745 (ST745). The isolates lacked additional emm-family genes and sof [6]. The strain was predicted to produce a low-activity extracellular NADase virulence protein (containing the G330D substitution) and lacked up-regulated nga operon. It was positive for the fibronectin binding protein genes prtF2 and sfb1, superantigen genes speC, speG, and smeZ, hyaluronic acid capsule gene hasA, and a hybrid tee-encoded pilus (T13/T28), and predicted to be uniformly antimicrobial-susceptible.

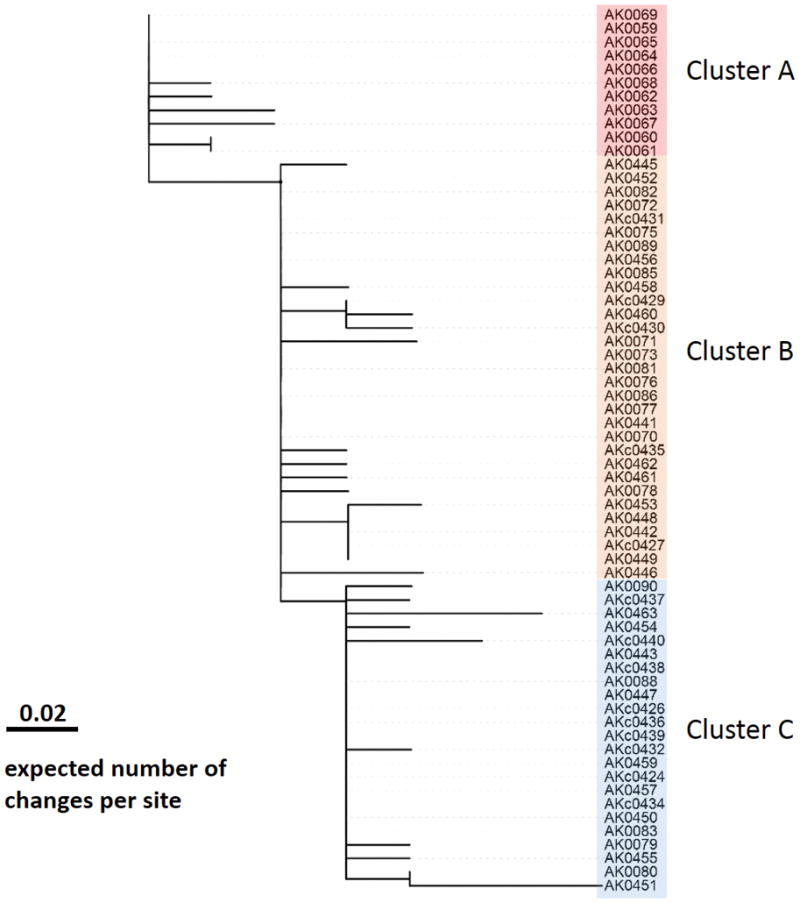

The 65 isolates with WGS data differed, on average, by two SNPs (range, 0–9) based on a total of 40 SNP loci across approximately 1.7M-bp shared genome. Three clusters of invasive disease and colonization isolates were evident based on the inferred genetic relatedness (Figure 3). The first genetic cluster (n=11) included all invasive disease cases from Fairbanks. The second two genetic clusters (Cluster B, n=31 and Cluster C, n=23) consisted of cases from Anchorage. Isolates from Cluster B were identified between July 2016 and May 2017 and from Cluster C between October 2016 and May 2017. The location, demographics, and clinical features of cases in the two clusters were similar. Cluster B included 5/14 colonization isolates, all of which were isolated in the baseline colonization survey. A higher proportion of colonization isolates (9 of 14) were categorized in Cluster C, including all four isolates from the follow-up survey.

Figure 3.

Maximum likelihood phylogeny based on a total of 40 shared-genome SNP sites of the 65 isolates. Scale bar represents expected number of changes per site. The label of colonization isolates begins with “AKc”. Cluster A includes 11 Fairbank isolates. Cluster B includes 31 Anchorage isolates, and Cluster C includes 23 Anchorage isolates. Isolates on a same vertical line were genomically indistinguishable.

Five independent SNPs (all non-synonymous) were located in the regulator operon covRS. These covRS mutations were found only in invasive isolates and not colonization isolates, consistent with their roles in invasive disease.

Discussion

We report on the first outbreak of invasive GAS to be identified in Alaska since surveillance began in 2000. The emm26.3 subtype was first detected in Alaska in 2016 and quickly spread among PEH; 42 cases were detected in Anchorage within 10 months. We characterized the strain clinically and genetically, and responded to the outbreak with a community-based antibiotic intervention.

Emm26.3 has rarely been reported, and the genetic and clinical aspects of emm26.3 have not been previously described. An emm26.3 strain, also ST745, was identified in Kenya in 2000 [30] and other subtypes of emm26 have been identified as uncommon causes of invasive disease in the Middle East [5]. The genome was typical of other pattern A-C strains in lacking the multifunctional sof gene, as well as the “emm-like” genes enn and mrp [6, 7, 28]. Also typical of many sof-negative strains was the presence of genes sfb1 and prtF2. The strain lacked the nga operon promoter upstream of the nga and slo (streptolysin O) genes present within the 3 most common invasive U.S. GAS clones (emm1/ST28, emm89/ST101, emm12/ST36) [28]. The strain also revealed GAS mitogenic exotoxin genes speC, speF, and smeZ, contained a mosaic tee gene (tee13/28) encoding the pilus backbone protein subunit, and were hasA-positive, consistent with production of the hyaluronic acid capsule.

The emergence of emm26.3 in Alaska echoes the emergence of emm59 throughout Canada and the U.S., which also spread among disadvantaged persons [17, 31]. Several conditions may have led to such an extensive outbreak of emm26.3. First, it is possible that the virulence factors associated with this strain led to increased transmission and severe disease. Second, when new or rare emm types are newly introduced to communities, the incidence of invasive GAS can increase as a result of low population immunity. Third, the outbreak centered on the homeless population, which is comprised of people who experience crowding, poor sanitation, skin breakdown, and who often have underlying medical conditions and substance use disorders. The PEH in Anchorage who were diagnosed with emm26.3 invasive GAS were older than patients with infections of other emm types, which also might have contributed to the severity of disease. More research is necessary to determine if the clinical differences between emm26.3 cases and non-emm26.3 cases were related to virulence factors, characteristics of the affected population, or both.

Although most invasive GAS infections occur sporadically throughout the community [19, 32], clusters of invasive GAS infections in healthcare settings and long-term care facilities are well documented [33–37]. CDC recommends considering testing staff who are found to be epidemiologically linked to GAS-infected persons for GAS colonization, and then providing antibiotics to attempt to eradicate colonization and prevent infection [22]. However, CDC recommendations for controlling outbreaks among PEH do not currently exist. The goal of our control efforts was to decrease GAS colonization and subsequent infection among homeless service clients in Anchorage. Given the estimates of the size of the Anchorage homeless population, we administered the intervention to approximately 40% of persons who we expect would be accessing services at the homeless services sites. After the intervention, only one case of emm26.3 was identified in a PEH in the following 11 weeks; this patient had not received antibiotics as a part of the outbreak intervention.

The outbreak investigation and response had some limitations. First, we were not able to characterize direct transmission patterns between outbreak patients because of unrecognized transmission between colonized persons. Additionally, the decline in cases and colonization could be caused by factors unrelated to our intervention, such as natural waning of the outbreak. However, colonization prevalence of emm11, which is often macrolide resistant, did not show a decline after the widespread administration of azithromycin, suggesting that the decline in emm26.3 might have been due to antibiotics rather than variation in overall GAS colonization. Finally, the small numbers of colonized persons and incident invasive disease cases limited our statistical power to conduct sub-analyses.

Outbreaks of invasive GAS among PEH present unique challenges, and data regarding effectiveness of response methods in this population are sparse [10, 15, 16, 38]. Although other factors might have contributed, we showed that a mass antibiotic campaign was temporally associated with a decline in both colonization and incidence of invasive GAS disease.

Supplementary Material

Summary.

We report on the investigation and control of an outbreak of invasive group A Streptococcus infections in the homeless population in Anchorage. A mass drug administration of a single dose of azithromycin was associated with a decrease in cases.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the Municipality of Anchorage, volunteers from South Central Foundation, Alaska Regional Hospital, and Providence Hospital, and the homeless service providers in Anchorage for their united front in responding to this outbreak. We would also like to thank the clinician and microbiology laboratory personnel of the hospitals participating in statewide surveillance for invasive group A streptococcal disease in Alaska and the entire staff at the Arctic Investigations Program for their contributions to this study

Footnotes

Potential conflicts of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Disclaimer:

“The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry.”

Contributor Information

Emily Mosites, Arctic Investigations Program, Division of Preparedness and Emerging Infections, National Center for Zoonotic and Emerging Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Anchorage, USA.

Anna Frick, Section of Epidemiology, Division of Public Health, Alaska Department of Health and Social Services, Anchorage, USA.

Prabhu Gounder, Arctic Investigations Program, Division of Preparedness and Emerging Infections, National Center for Zoonotic and Emerging Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Anchorage, USA.

Louisa Castrodale, Section of Epidemiology, Division of Public Health, Alaska Department of Health and Social Services, Anchorage, USA.

Yuan Li, Respiratory Disease Branch, Division of Bacterial Diseases, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, USA.

Karen Rudolph, Arctic Investigations Program, Division of Preparedness and Emerging Infections, National Center for Zoonotic and Emerging Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Anchorage, USA.

Debby Hurlburt, Arctic Investigations Program, Division of Preparedness and Emerging Infections, National Center for Zoonotic and Emerging Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Anchorage, USA.

Kristen D. Lecy, Arctic Investigations Program, Division of Preparedness and Emerging Infections, National Center for Zoonotic and Emerging Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Anchorage, USA

Tammy Zulz, Arctic Investigations Program, Division of Preparedness and Emerging Infections, National Center for Zoonotic and Emerging Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Anchorage, USA.

Tolu Adebanjo, Respiratory Disease Branch, Division of Bacterial Diseases, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, USA.

Jennifer Onukwube, Respiratory Disease Branch, Division of Bacterial Diseases, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, USA.

Bernard Beall, Respiratory Disease Branch, Division of Bacterial Diseases, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, USA.

Chris A. Van Beneden, Respiratory Disease Branch, Division of Bacterial Diseases, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, USA

Thomas Hennessy, Arctic Investigations Program, Division of Preparedness and Emerging Infections, National Center for Zoonotic and Emerging Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Anchorage, USA.

Joseph McLaughlin, Section of Epidemiology, Division of Public Health, Alaska Department of Health and Social Services, Anchorage, USA.

Michael Bruce, Arctic Investigations Program, Division of Preparedness and Emerging Infections, National Center for Zoonotic and Emerging Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Anchorage, USA.

References

- 1.Bennett John E, Dolin Raphael, Blaser MJ. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 8. Vol. 2. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 2015. Part III Infectious Diseases and Their Etiologic Agents: Section G. Gram-Positive Cocci. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nelson GE, Pondo T, Toews KA, et al. Epidemiology of Invasive Group A Streptococcal Infections in the United States, 2005–2012. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2016;63(4):478–86. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Active Bacterial Core Surveillance Report, Emerging Infections Program Network, Group A Streptococcus—2015. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.CDC Arctic Investigations Program. Surveillance of Invasive Bacterial Disease in Alaska, 2015. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steer AC, Law I, Matatolu L, Beall BW, Carapetis JR. Global emm type distribution of group A streptococci: systematic review and implications for vaccine development. The Lancet Infectious diseases. 2009;9(10):611–6. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70178-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bessen DE, Sotir CM, Readdy TL, Hollingshead SK. Genetic correlates of throat and skin isolates of group A streptococci. The Journal of infectious diseases. 1996;173(4):896–900. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.4.896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanderson-Smith M, De Oliveira DM, Guglielmini J, et al. A systematic and functional classification of Streptococcus pyogenes that serves as a new tool for molecular typing and vaccine development. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2014;210(8):1325–38. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dinis M, Plainvert C, Kovarik P, Longo M, Fouet A, Poyart C. The innate immune response elicited by Group A Streptococcus is highly variable among clinical isolates and correlates with the emm type. PloS one. 2014;9(7):e101464. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Engelthaler DM, Valentine M, Bowers J, et al. Hypervirulent emm59 Clone in Invasive Group A Streptococcus Outbreak, Southwestern United States. Emerging infectious diseases. 2016;22(4):734–8. doi: 10.3201/eid2204.151582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Athey TB, Teatero S, Sieswerda LE, et al. High Incidence of Invasive Group A Streptococcus Disease Caused by Strains of Uncommon emm Types in Thunder Bay, Ontario, Canada. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2016;54(1):83–92. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02201-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erdem G, Abe L, Kanenaka RY, et al. Characterization of a community cluster of group a streptococcal invasive disease in Maui, Hawaii. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2004;23(7):677–9. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000130956.47691.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turner CE, Abbott J, Lamagni T, et al. Emergence of a New Highly Successful Acapsular Group A Streptococcus Clade of Genotype emm89 in the United Kingdom. mBio. 2015;6(4):e00622. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00622-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lancefield RC. Persistence of type-specific antibodies in man following infection with group A streptococci. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1959;110(2):271–92. doi: 10.1084/jem.110.2.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wannamaker L. The epidemiology of streptococcal infections. In: McCarty M, editor. Streptococcal Infections. New York: Columbia University Press; 1953. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cady A, Plainvert C, Donnio P, et al. Clonal spread of Streptococcus pyogenes emm44 among homeless persons, Rennes, France. Emerging infectious diseases. 2011;17(2):315–7. doi: 10.3201/eid1702.101022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bundle N, Bubba L, Coelho J, et al. Ongoing outbreak of invasive and non-invasive disease due to group A Streptococcus (GAS) type emm66 among homeless and people who inject drugs in England and Wales, January to December 2016. Eurosurveillance. 2017;22(3) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.3.30446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tyrrell GJ, Lovgren M, St Jean T, et al. Epidemic of group A Streptococcus M/emm59 causing invasive disease in Canada. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2010;51(11):1290–7. doi: 10.1086/657068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Department of Housing and Urban Development. Sheltered Homeless Persons in Anchorage. Available at: http://anchoragehomeless.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Anchorage-2015-AHAR-Report.pdf.

- 19.Rudolph K, Bruce MG, Bruden D, et al. Epidemiology of Invasive Group A Streptococcal Disease in Alaska, 2001 to 2013. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2016;54(1):134–41. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02122-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guchev I, Gray G, Klochkov O. Two Regimens of Azithromycin Prophylaxis against Community-Acquired Respiratory and Skin/Soft-Tissue Infections among Military Trainees. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2004;38:1095–1101. doi: 10.1086/382879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schonwald S, Kuzman I, Oreskovic K, et al. Azithromycin: single 1. 5 g dose in the treatment of patients with atypical pneumonia syndrome--a randomized study. Infection. 1999;27(3):198–202. doi: 10.1007/BF02561528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shelby-James TM, Leach AJ, Carapetis JR, Currie BJ, Mathews JD. Impact of single dose azithromycin on group A streptococci in the upper respiratory tract and skin of Aboriginal children. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2002;21(5):375–80. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200205000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Physician’s Desk Reference. 71. Montvale, NJ: PDR, LLC; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Institute CaLS. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: Twenty-first informational supplement M100–S21. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Protocol for emm typing. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/streplab/protocol-emm-type.html.

- 26.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Streptococcus Laboratory; Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/streplab/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Streptococcus Laboratory; [Accessed 5/3/17]. Available at: https://www2a.cdc.gov/ncidod/biotech/strepblast.asp. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chochua S, Metcalf BJ, Li Z, et al. Population and Whole Genome Sequence Based Characterization of Invasive Group A Streptococci Recovered in the United States during 2015. mBio. 2017;8(5) doi: 10.1128/mBio.01422-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Index of Infectious Diseases. Available at: ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/infectious_diseases/biotech/tsemm/

- 30.Bessen D. Public databases for molecular typing and microbial genome diversity: Full information on isolate K5721. Available at: https://pubmlst.org/bigsdb?page=info&db=pubmlst_spyogenes_isolates&id=2501.

- 31.Fittipaldi N, Beres SB, Olsen RJ, et al. Full-genome dissection of an epidemic of severe invasive disease caused by a hypervirulent, recently emerged clone of group A Streptococcus. The American journal of pathology. 2012;180(4):1522–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Active Bacterial Core Surveillance Report, Emerging Infections Program Network, Group A Streptococcus 2013. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beaudoin AL, Torso L, Richards K, et al. Invasive group A Streptococcus infections associated with liposuction surgery at outpatient facilities not subject to state or federal regulation. JAMA internal medicine. 2014;174(7):1136–42. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chalker VJ, Smith A, Al-Shahib A, et al. Integration of Genomic and Other Epidemiologic Data to Investigate and Control a Cross-Institutional Outbreak of Streptococcus pyogenes. Emerging infectious diseases. 2016;22(6):973–80. doi: 10.3201/eid2206.142050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dooling KL, Crist MB, Nguyen DB, et al. Investigation of a prolonged Group A Streptococcal outbreak among residents of a skilled nursing facility, Georgia, 2009–2012. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2013;57(11):1562–7. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mahida N, Beal A, Trigg D, Vaughan N, Boswell T. Outbreak of invasive group A streptococcus infection: contaminated patient curtains and cross-infection on an ear, nose and throat ward. The Journal of hospital infection. 2014;87(3):141–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tezer Tekce Y, Erbay A, Unaldi O, Cabadak H, Sen S, Durmaz R. An outbreak of Streptococcus pyogenes surgical site infections in a cardiovascular surgery department. Surgical infections. 2015;16(2):151–4. doi: 10.1089/sur.2014.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Finkelstein M. Outbreak of invasive Group A Streptococcus at a homeless shelter. Toronto, Ontario: Mosites E; 2016. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.