Abstract

Objectives

Experiences of racial discrimination have been associated with diverse negative health outcomes among racial minorities. However, extant findings of the association between racial discrimination and alcohol behaviors among Black college students are mixed. The current study examined mediating roles of depressive symptoms and coping drinking motives in the association of perceived racial discrimination with binge drinking and negative drinking consequences.

Design

Data were obtained from a cross-sectional study of Black college students attending a predominantly White institution in the northeastern US (N = 251, 66% female, mean age = 20 years).

Results

Results from path analysis showed that, when potential mediators were not considered, perceived racial discrimination was positively associated with negative drinking consequences but not frequency of binge drinking. Serial multiple mediation analysis showed that depressive symptoms and in turn coping drinking motives partially mediated the associations of perceived racial discrimination with both binge drinking frequency and negative drinking consequences (after controlling for sex, age, and negative life events).

Conclusions

Perceived racial discrimination is directly associated with experiences of alcohol-related problems, but not binge drinking behaviors among Black college students. Affective responses to perceived racial discrimination experiences and drinking to cope may serve as risk mechanisms for alcohol-related problems in this population. Implications for prevention and intervention efforts are discussed.

Keywords: Alcohol, black, college students, racial discrimination, depression, coping motives

Introduction

College campuses in the U.S. are becoming increasingly racially diverse (U.S. Department of Education 2016). However, much of the research on college drinking has neglected racial minorities (Broman 2005). This scarce attention to college drinking behaviors among racial minorities is concerning given that literature has posited against the ‘one size fits all’ approach (i.e. assumption that racial minorities are equally exposed and vulnerable to the same risk factors as White students; Alegria et al. 2010; Brown et al. 2001; Wallace and Muroff 2002). Research focusing solely on Blacks has been called for in efforts to broaden our understanding of alcohol use and consequences within this racial group (Zapolski et al. 2014).

Although binge drinking and its associated negative consequences among college students of diverse racial backgrounds remain a serious public health concern (Barnes et al. 2010; Blanco et al. 2008), notable racial differences exist in college drinking patterns. For example, Black students are more likely to abstain from alcohol use and, when they drink, engage in fewer binge-drinking episodes and consume a lower quantity of alcohol than their White peers (Barnes et al. 2010; O'Malley and Johnston 2002; Siebert and Wilke 2007; Randolph et al. 2009). Interestingly, recent findings indicate that, despite their lower levels of alcohol use, Black college students exhibit similar levels of negative drinking consequences (e.g. alcohol dependence symptoms, and physical, social and legal consequences from drinking) as compared to White college students (Barnett et al. 2014; Clarke et al. 2013). Moreover, after entering into young adulthood, while the rate of binge drinking substantially decreases among Whites, it remains relatively stable for Black adults (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA] 2016). Black adults' experience of negative drinking consequences rises rapidly across young adulthood such that Black adults report more negative drinking consequence than Whites, even after accounting for alcohol consumption (Mulia et al. 2009; Witbrodt et al. 2014). Given this unique pattern of drinking behaviors, it is important to examine risk factors for and mechanisms underlying binge drinking and negative drinking consequences among Black college students (Martin et al. 2013).

In addition to the generic challenges that accompany college life, Black college students (particularly those attending predominantly White institutions) may face a number of unique difficulties (Smedley, Myers, and Harrell 1993). In particular, racial discrimination has been suggested as a racially relevant stressor for adverse physical and mental health outcomes and high-risk behaviors among Black adults (Harrell 2000; Harrell, Merritt, and Kalu 1998). Racial discrimination is defined as a ‘special form of social ostracism in which phenotypic characteristics (i.e. skin color) are used to assign individuals to an outcast status, rendering them targets of social exclusion, harassment, and unfair treatment’ (Brondolo et al. 2009). Indeed, racial discrimination experiences have been shown to be associated with an array of adverse health behaviors and outcomes including alcohol use in racially diverse samples (for review, see Williams and Mohammed 2009).

However, findings regarding the association of racial discrimination with college alcohol outcomes has been inconsistent, with some positive (Blume et al. 2012; Broman 2007) and null (Boynton et al. 2014) findings. These mixed findings may be due to the extant studies' differences in alcohol variables under examination and racial composition of samples. Regarding alcohol use behaviors (e.g. frequency-quantity index, binge drinking), studies of racially diverse samples have reported a positive association with racial discrimination (e.g. Blume et al. 2012; Broman 2007), whereas, studies of solely Black collegestudents have reported a null association (e.g. Boynton et al. 2014). Regarding negative drinking consequences, however, research consistently reports its positive association with racial discrimination among all Black college students (Boynton et al. 2014) and racially diverse samples of students (Blume et al. 2012; Broman 2007; Grekin 2012).Further investigation into individual differences within Black college students is warranted to reconcile the extant mixed findings in the association of racial discrimination with alcohol use versus negative drinking consequences.

Moreover, there is still a paucity of empirical evidence for the mechanisms underlying the association of racial discrimination with drinking behavior. This association may be sequentially explained by the experience of distress (i.e. the stress response) due to perceived racial discrimination and in turn drinking motives to cope with this distress. The central tenet of the tension-reduction and self-medication models of drinking is that people drink alcohol to alleviate an aversive state of distress, such as depression, anxiety, frustration, and anger (Greeley and Oei 1999). A biopsychosocial model of racism as a stressor also posits that perceived discriminatory experiences lead to exaggerated psychological and physiological stress responses, which in turn increase maladaptive behaviors, such as problematic drinking, to cope with discriminatory experiences (Clark et al. 1999). Indeed, depressive symptoms have been shown to partially mediate the effects of racial discrimination on alcohol-related problems in Black students attending a historically Black university (Boynton et al. 2014). However, the remaining significant direct effect of discrimination on alcohol problems (after accounting for the mediating effect of depressive symptoms) suggests the presence of additional mediating factors that may explain the discrimination-alcohol association. For example, in a national study of Black adult workers, coping drinking motives were found to partially mediate the relationship between experiences of racial discrimination and drinking problems (Martin, Tuch, and Roman 2003). However, to date, research has not examined the role of both depressive symptoms and coping drinking motives as serial mediators of the racial discrimination and alcohol behaviors relationship.

The current study aimed to clarify the association of perceived racial discrimination with binge drinking and negative drinking consequences in a sample of Black college students on a predominantly White campus. Specifically, we aimed to examine, first, whether perceived racial discrimination was associated with binge drinking and negative drinking consequences; and second, whether depressive symptoms and in turn coping drinking motives sequentially mediated these associations. It was hypothesized that perceived racial discrimination would be positively associated with negative drinking consequences directly, but not with binge drinking days. Also, it was hypothesized that racial discrimination would be positively associated with depressive symptoms, and in turn coping motives, which would be associated with binge drinking and negative drinking consequences.

Method

Participants and procedures

Data were obtained from a cross-sectional study of 251 Black students attending a predominantly White 4-year private university in the northeastern United States. Participants were recruited through an undergraduate research participation pool, email invitations through electronic mailing listservs of various Black student organizations, flyers across campus, and a snowball sampling technique. Students were eligible for this study if they met the following inclusion criteria: (1) currently enrolled in college, (2) 18 years of age or older, (3) self-identified as being of the Black race and (4) consumed alcohol at least once in the past 30 days.

All study measures and procedures were approved by the university's institutional review board. After confirming eligibility, written informed consent was obtained from each participant upon arrival to the lab. Eligible students completed a paper-and-pencil questionnaire on diverse health behaviors and provided a saliva sample for genotyping for a genetic part of the study. Students recruited through the university research pool (63% of the total sample) were compensated with research credit, and those recruited through other methods (37%) were compensated with $15. A few participants (3%; n = 7) also received up to an additional $15 gift card to Starbucks for referring eligible participants ($5 per referral, up to 3 referrals permitted).

Measures

Demographics

Age and sex (1 = male and 0 = female) were assessed. These two demographic variables were included as covariates to control for its potential confounding effects on college drinking (Johnston et al. 2006).

Negative life events

The Life Events Scale for Students (Linden 1984) was used to assess experience of 36 events (e.g. ‘Seriously thought about dropping out of college’) by asking For each event below, please indicate if the event has happened in the past year by circling either Yes or No. Then, if you experienced the event, indicate how positively or negatively you perceived that event on the scale to the right by circling one number from −2 (extremely negative) to 2 (extremely positive); if it has not happened in the last year, leave it blank. Of the 36 events included in the checklist, only events experienced and endorsed as negative (events rated at −1 or −2) were used to calculate each participant's total count of negative life events experienced in the past year, which was included as a covariate in the analyses. This measure has been used to assess stressful life events in Black college students (e.g. Kranzler et al. 2012). This number of negative life events experienced were included as a covariate (along with sex and age) to control for its potential confounding effects on drinking behaviors as well as perceived racial discrimination (Camatta and Nagoshi 1995; Murry et al. 2001).

Perceived racial discrimination

The Perceived Ethnic Discrimination Questionnaire (Contrada et al. 2001) was used to assess the frequency of experiencing acts of discrimination that have been directed against or toward individuals during the past three months. This scale has been used to assess perceived racial discrimination experiences and their association with mental health outcomes among Black college students (e.g. Pieterse et al. 2010). The 17-item scale includes items such as ‘Have you been subjected to ethnic name calling?’ and ‘Others had low expectations of you because of your ethnicity?’ Students were asked to respond on a 7-point scale (1 = Never to 7 = Very often). A sum score (Cronbach's alpha = .88) was used for analyses, which is most commonly used among studies of college students and young adults in the relation with diverse mental health outcomes (for review, see Atkins 2014).

Depressive symptoms

The 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale Revised (Eaton et al. 2004) was used to assess an array of affective and behavioral depressive symptoms experienced within the past week, such as ‘My appetite was poor,’ ‘I had crying spells,’ and ‘I could not get going.’ Participants responded to each item based on four response options (0 = rarely or none of the time to 3 = most or all of the time). A sum score (Cronbach's alpha = .87) was used for analyses, as suggested in the original scale. Depressive symptoms have been suggested to be one of indicators of stress responses in the context of tension-reduction and stress-response dampening models of alcohol use and alcoholism (Greeley and Oei 1999, 25) and utilized in studies of similar aims in Black college students (e.g. Boynton et al. 2014).

Coping drinking motives

The five-item coping motive subscale from the Drinking Motives Questionnaire-Revised (Cooper 1994) was used to assess frequency of drinking to cope with negative emotions, such as ‘Drink to forget about your problems’ and ‘Drink because it helps you when you feel depressed or nervous’. Participants responded to each item using a 5-point scale (1 = almost never/never to 5 = almost always/always). A sum score (Cronbach's alpha = .85) was used for analyses, which is most commonly used among studies of college students and young adults (e.g. Lecci, MacLean, and Croteau 2002; Merrill, Wardell, and Read 2014). This scale has been used to assess drinking motives in the association with diverse alcohol behaviors among Blacks in the S (e.g. Cooper et al. 2008).

Binge drinking days

To assess the number of binge drinking days over the past 30 days (defined as the number of days that participants consumed four or more drinks for women, and five or more drinks for men; SAMHSA 2016), a paper-pencil version of the Timeline Follow Back calendars was administered (Sobell and Sobell 1992). Participants were presented with a calendar and asked to record the number of standard drinks they consumed on each day over the past 30 days. The definition of a drink was given to participants as a 12-oz. can or bottle of beer, a 5-oz. glass of wine, 8-oz. glass of malt liquor, or 1.5 oz. of hard liquor straight or in a mixed drink. Pictures of these standard drinks were also given. Memory aids were provided by noting special events on the calendars (e.g. holidays; school days off; major school, community, and sports events) to enhance recollection of possible drinking days. The paper-and-pencil administration of the Timeline Follow Back calendars has demonstrated sound validity and reliability in Black and racially diverse college students (e.g. Humara and Sherman 1999; Sobell et al. 1986).

Negative drinking consequences

The 23-item Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (White and Labouvie 1989) was used to assess the frequency of experiencing diverse negative consequences from drinking (e.g. ‘Went to work or school high or drunk’ and ‘Neglected your responsibility’) by asking ‘how many times has this happened to you while you were drinking or because of your drinking during the past 3 months?’ Participants responded to the items on a 4-point scale (0 = none to 3 = more than five times). A sum score (Cronbach's alpha = .83) was used for analyses, as suggested in the original scale. This scale has been used in studies of the association between racial discrimination and negative consequences among predominantly Black college students (e.g. Blume et al. 2012).

Data analytic strategies

Descriptive statistics were attained using SPSS, Version 23. To test our hypothesized serial multiple mediation models (with two mediators in sequence), path analyses were conducted using Mplus, Version 7 (Muthén and Muthén [1998] 2012), a structural equation modeling software package. Path analysis is an extension of linear regression and results from path analysis can be interpreted in a similar way as results from regression analyses. However, path analysis estimates complex causal relationships among multiple predictors, mediators, and outcomes in a single model simultaneously; thus, it is a more efficient way of testing our hypothesized complex mediating relationships. Maximum likelihood parameter estimation with robust standard errors was used to accommodate missing data and deal with non-normality of alcohol outcome variables (as evidenced by skewness and kurtosis values greater than ± 1). Both binge drinking days and negative drinking consequences were specified as count outcomes, given that they were characterized by discrete, non-negative integer values representing a number of occurrences. The binge drinking days outcome was modeled with a Poisson distribution (M = 2.92; variance = 12.57; dispersion parameter = 0.26, p = .16), whereas frequency of negative consequences (M = 7.87; variance = 47.08; dispersion parameter = 0.23, p = .01) was modeled with a negative binomial distribution due to its significant overdispersion (Hilbe 2011). Monte Carlo integration was used to model the influence of continuous mediators on count outcomes. Residual error covariances between count outcomes were modeled by specifying a latent variable that influenced both outcomes. As an effect size measure for each path, standardized regression coefficients are presented for paths with the two continuous mediators (i.e. depressive symptoms and coping motives), and incidence rate ratios (IRRs) are presented for paths with the two count alcohol outcomes. IRRs measure the percent increase/decrease in the outcome with a one-unit increase in the predictor/covariate, with an IRR of 1 indicating no change in the outcome with a one-unit increase in the predictor/covariate. For example, an IRR of 1.02 indicates a 2% increase in the outcome with a one-unit increase in the predictor/covariate.

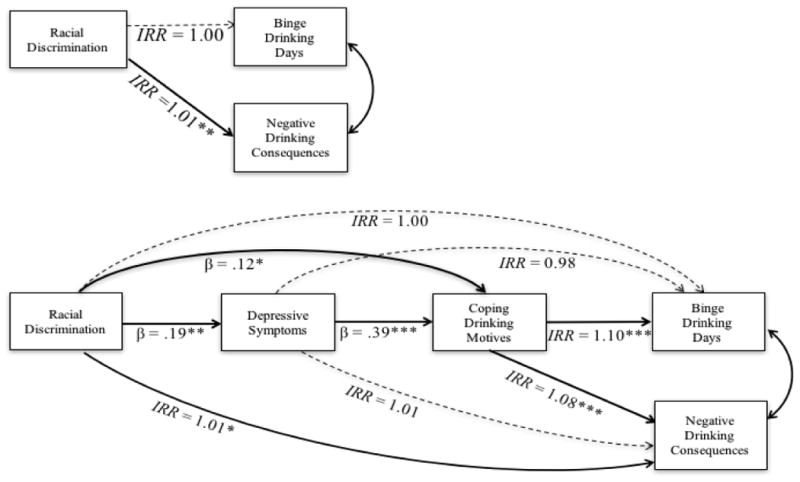

For main analyses, two fully saturated path models (and thus no model fit indices) were estimated. Participant sex, age and negative life events were included as covariates in both path models (their coefficients were not shown in figures for simplicity). The first path model (shown in Figure 1, top panel) aimed to test the total effect of racial discrimination on alcohol use and in turn negative drinking consequences (X→Y1, 2, without mediators in the model). The two alcohol outcomes of binge drinking days and negative drinking consequences (Y1, 2) were allowed to covary.

Figure 1.

N = 249. Path coefficients obtained from a path model to test the total effects (without mediators) in the top panel, and a path serial multiple meditational model in the bottom panel. Standardized coefficients for paths predicting continuous outcomes (depressive symptoms and coping motives) and incidence rate ratios (IRR) for paths predicting count outcomes (binge drinking and negative drinking consequences) are shown. Dotted paths indicate non-significant paths. Sex, age and negative life events were included as covariates; their path coefficients are not displayed for simplicity.

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p<.001.

The second path model (shown in Figure 1, bottom panel) aimed to test the serial mediating role of two variables in sequence (i.e. depressive symptoms and coping motives) in the effect of racial discrimination on the two alcohol outcomes. Paths from racial discrimination to the alcohol outcomes through depressive symptoms and coping motives represented the indirect paths (i.e. indirect effects of the predictor on the outcomes through the mediators). These indirect paths included a path from racial discrimination to the first mediator of depressive symptoms (a path of X→M1), a path from depressive symptoms to coping motives (d path ofM1→M2), as well as paths from coping motives to binge drinking (b1 path of M2 → Y1) and to negative consequences (b2 path of M2 → Y2). Thus, the indirect effect through depressive symptoms and coping motives in sequence in the association of racial discrimination with binge drinking was calculated by multiplying unstandardized coefficients of the three indirect paths (a path * d path * b1 path); the indirect effect through depressive symptoms and coping motives in sequence in the association of racial discrimination with negative drinking consequences was calculated by multiplying unstandardized coefficients of the three indirect paths (a path *d path * b2 path). Because the Sobel test has been shown to lack in power (MacKinnon et al. 2002) and bootstrapping is not available with Monte Carlo numerical integration, confidence intervals of the indirect effects were computed with the Monte Carlo method, which has been shown to perform comparatively to other widely used methods of confidence interval estimation for indirect effects (Preacher and Selig 2012). Significance testing was performed using an online Monte Carlo calculator (Selig and Preacher 2008) that generated 95% confidence intervals (CI) of the indirect effects based on 20,000 resamples; CIs that did not include zero indicated significant mediation. Paths from racial discrimination to binge drinking (c1′ path of X→Y1) and to negative consequences (c2′ path of X→Y2) represented direct effects, after accounting for sequentially mediated effects (as well as covariates). Although they were not part of our hypothesized serial mediation, a path from racial discrimination to the second mediator of coping motives (X→M2), and paths from depressive symptoms to binge drinking (M1 → Y1) and to negative consequences (M1 → Y2) were also estimated to avoid potential bias in estimates due to omitted paths.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Means (with standard deviations in parentheses) or percentages of all study variables and bivariate Pearson correlation coefficients are presented in Table 1. Participants were, on average, 20.01 years old (SD = 4.03, range = 18−53), 66% female, 13.2% fraternity/sorority members, and 38% first year students. On average, students engaged in binge drinking on three of the past 30 days, similar to levels observed among other samples of Black college students (O'Hara et al. 2015). Bivariate correlation coefficients revealed significant, positive associations of racial discrimination with depressive symptoms, coping motives, and negative drinking consequences, but not with binge drinking days at p < .05.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations among Study Variables.

| Variable (possible range; α if applicable) | M (%) | SD | r | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |||

| 1. Age | 20.01 | 4.03 | — | ||||||

| 2. Sex (0 = female; 1 = male) | 34% | .03 | — | ||||||

| 3. Negative life events (0 – 36) | 3.84 | 2.87 | –.01 | –.12 | — | ||||

| 4. Racial discrimination (17 – 119; α = .88) | 36.95 | 15.03 | –.01 | .16* | .25*** | — | |||

| 5. Depressive symptoms (0 – 60; α = .87) | 13.87 | 8.88 | –.00 | –.09 | .42*** | .27*** | — | ||

| 6. Coping drinking motives (5 – 25; α = .85) | 9.16 | 4.31 | .05 | –.09 | .24** | .23*** | .45*** | — | |

| 7. Binge drinking days (0 – 30) | 2.92 | 3.54 | .08 | .13* | –.01 | –.01 | –.03 | .22*** | — |

| 8. Negative drinking consequences (0 – 69; α = .83) | 7.87 | 6.86 | .10 | .15* | .25*** | .30*** | .32*** | .49*** | .35*** |

Note. N = 249-251.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Path model 1: tests for the total effect of racial discrimination (without mediators)

As shown in Figure 1, top panel, congruent with our hypotheses, perceived racial discrimination was positively associated with negative drinking consequences (b = 0.01 [95% bootstrapped CI = 0.01, 0.02], SE = 0.004, IRR = 1.01, p = .001). However, perceived racial discrimination was not significantly associated with binge drinking days (b = −0.001 [95% bootstrapped CI = −0.01, 0.01], SE = 0.01, IRR = 1.00, p = .84), after controlling for covariates of sex, age and negative life events.

Path model 2: tests for mediating effects of depressive symptoms and coping motives

As shown in Figure 1, bottom panel, congruent with our hypotheses, significant serial mediated paths from racial discrimination to depressive symptoms, coping motives, binge drinking days and negative consequences were found, after controlling for covariates of sex, age and negative life events. Specifically, racial discrimination was positively associated with depressive symptoms, (b = 0.11, SE = 0.04, β = .19, p = .002), which in turn were positively associated with coping drinking motives (b = 0.19, SE = 0.04, β = .39, p < .001). In turn, coping motives were positively associated with binge drinking (b = 0.10, SE = 0.02, IRR = 1.10, p < .001), as well as negative drinking consequences (b = 0.08, SE = 0.01, IRR = 1.08, p < .001). Small but significant serial indirect/mediated effects via depressive symptoms and coping were in sequence found for binge drinking (point unstandardized estimate = 0.002, 95% bootstrapped CI = 0.001, 0.004) and negative drinking consequences (point unstandardized estimate = 0.002, 95% bootstrapped CI = 0.001, 0.003).

Even after accounting for these hypothesized mediated associations and covariates, racial discrimination was also directly and positively associated with negative drinking consequences b = 0.01, SE = 0.004, IRR = 1.01, p = .045. These significant direct effects of racial discrimination on negative drinking consequences indicated partial mediation (as opposed to full mediation) via depressive symptoms and coping motives.

Discussion

This study extends the literature by demonstrating not only an association of perceived racial discrimination with high-risk and problematic alcohol behaviors but also serial mediating pathways in the association among Black college students. Specifically, results showed that, when no mediators were considered, perceived discrimination was positively and directly associated with negative drinking consequences, but not with number of binge drinking days. Furthermore, depressive symptoms and in turn coping drinking motives partially mediated the relationship of racial discrimination with both binge drinking and negative drinking consequences. This is to our knowledge the first demonstration of depressive symptoms and coping motives as serial mediators in the associations between perceived discrimination and alcohol outcomes among Black college students. Further, our findings contribute to the better understanding of affective and cognitive sequential mechanisms underlying disparities in negative drinking consequences among Black college drinkers.

Results showed that perceived racial discrimination was not directly associated with number of binge drinking days. This finding is parallel to prior research among a Black college student sample (e.g. Boynton et al. 2014) but diverts from findings in racially diverse samples (e.g. Broman 2007). These results indicate that findings of binge drinking from racially diverse samples including both Whites (who on average tend to report lower levels of racial discrimination but higher levels of binge drinking) and Blacks (who on average tend to report higher levels of racial discrimination but lower levels of binge drinking) cannot be directly compared with findings from all-Black samples. In contrast, our finding of the positive and direct association of discrimination with negative drinking consequences is in line with prior findings in college students of diverse racial groups (Broman 2007; Grekin 2012) as well as in Black college students (Boynton et al. 2014). This finding corroborates foregoing research, which suggests that Black individuals experience greater negative drinking consequences regardless of their concurrent level of alcohol consumption patterns (Mulia et al. 2009). Conservative cultural norms against alcohol use and fear of exemplifying negative racial stereotypes may contribute to lower levels of alcohol use despite racial discrimination experiences (Herd 1994). Paradoxically, these same factors may also be contributing to greater social consequences (e.g. problems with family members and friends) when one partakes in drinking. Further, low access to and utilization of medical and mental health services, variations in alcohol-metabolizing genes, and strict law enforcement may lead to greater medical and legal consequences from drinking among Black individuals as compared to White individuals (Chartier and Caetano 2010). These findings of the association between racial discrimination and negative drinking consequences is consistent with the larger literature regarding the association of diverse forms and indicators of distress (e.g. trauma and post-traumatic stress symptoms) with negative drinking consequences (e.g. Read et al. 2012) For example, in college women of diverse racial backgrounds, childhood sexual abuse was associated with negative drinking consequences but not with binge drinking (Smith, Smith, and Grekin 2014). Taken together, drinking in response to stressful experiences may be especially relevant to negative drinking consequences, as opposed to alcohol use and binge drinking.

Our findings also highlight underlying sequential affective and cognitive mechanisms (i.e. depressive symptoms and in turn coping motives) underlying the association of a culturally relevant antecedent (i.e. racial discrimination) with binge drinking and negative drinking consequences among Black college students. These findings are aligned with a biopsychosocial model of racism as a stressor (Clark et al. 1999) such that discriminatory experiences lead to stress responses, which in turn lead to motives to cope with the aversive state of distress by engaging in maladaptive behaviors such as problematic drinking. The novel finding of coping motives as a second mediator of the association also supports the role of drinking motives as the final antecedent of drinking behaviors, congruent with the motivational model of alcohol use (Cooper 1994; Cox and Klinger 1988). Although a recent study of Black students attending a historically Black university (Boynton et al. 2014) found a mediating role of depressive symptoms in the effects of racial discrimination on alcohol-related problems, our study extends the existing finding to serial mediating roles of depressive symptoms and coping drinking motives among Black college students attending a predominantly White institution. Moreover, our results provide convincing evidence for detrimental effects of perceived racial discrimination over and above general negative life events (as well as sex and age), by controlling for significant and positive effects of negative life events with both racial discrimination and negative drinking consequences (see Table 1; r's = .25, p < .001). This finding also corroborates results from previous studies showing that coping drinking motives to deal with stress increases the risk of alcohol misuse and alcohol-related problems rather than risk of alcohol use and binge drinking (e.g. Read et al. 2003). Even after accounting for the significant serial mediation of depression symptoms and coping motives, however, there remained a significant direct association between racial discrimination and negative consequences. This finding suggests that there are still additional mediational pathways and/or potential moderating factors remained unaccounted for. For example, diverse affective reactions to discriminatory experiences besides depressive symptoms (e.g. anger; Boynton et al. 2014) or tension-reduction alcohol expectancy may act as additional mediators. Further, suppressive coping styles (Clark et al. 1999) or coping drinking motives may act as a moderator, as well as a mediator (e.g. Smith, Smith, and Grekin 2014).

Understanding racially relevant risk factors for alcohol use and related consequences in Black college students can ultimately inform prevention and intervention strategies. Research has called for more efficacious, racially sensitive interventions for Black students. For example, a recent meta-analysis demonstrated that existing college alcohol interventions may be less successful in schools with a higher percentage of Black students (Scott-Sheldon et al. 2014). The lack of research regarding culturally specific mechanisms underlying problematic drinking among this population has limited alcohol intervention efficacy. In an effort to help college students mitigate the effects of racial discrimination, interventions may seek to strengthen one's racial identity (defined as one's sense of racial group membership that involves a sense of belonging, preference for, and positive evaluation of one's racial group; Sellers et al. 1998). Strong racial identity has demonstrated capabilities to buffer the effects of stress exposure and subsequently reduce alcohol use among Blacks (Fuller-Rowell et al. 2012; Richman et al. 2013). Moreover, individuals who experience discrimination tend to adopt adverse strategies for coping with their negative experiences, including rumination and suppression (Hatzenbuehler, Nolen-Hoeksema, and Dovidio 2009). Treatment may seek to validate individual's experiences, while also offering emotion regulation techniques to aid with the emotional sequel of perceived discrimination. Also, college campuses should strive to increase social support options for Black students (e.g. multicultural organizations) to help students cope with culturally specific stressors.

Limitations and future directions

Notwithstanding our contributions to the discrimination and alcohol behaviors literature, our findings should be interpreted within the context of some limitations. Although our finding is in line with our proposed serial multiple mediation model, due to the reliance on cross-sectional data and the varying timeframes of the used measures, any conclusions about causality cannot be drawn. Future longitudinal studies with multiple assessment points are needed to provide further support for the serial mediational pathways underlying the effects of racial discrimination on diverse alcohol behaviors and outcomes. The self-report nature of the data also presents concerns given the subjective measure of racial discrimination. It is possible that students may under- or over- report and may have difficulties remembering experiences of discrimination and drinking behaviors. Moreover, this study focused on college students, which limits generalizability to other populations. Future large-scale multi-wave prospective studies should attempt to replicate our findings in different samples (e.g. community samples with diverse socioeconomic status). Further, given the emerging but mixed findings for sex differences in the discrimination-alcohol association (e.g. Boynton et al. 2014; Clark 2004; O'Hara et al. 2015), well powered future research needs to test whether mechanisms underlying the association may differ across sex.

Conclusion

Perceived racial discrimination is associated with alcohol-related problems (but not binge drinking) among Black college student drinkers. Discriminatory experiences are not only associated with negative affect but also coping motives, both of which in turn are associated with negative drinking consequences. Our findings add to the body of knowledge on racially relevant risk pathways that contribute to racial disparities in the experience of negative drinking consequences. There is a need for continued research on racial discrimination as well as prevention and intervention strategies to combat its detrimental effects on drinking behaviors and outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by NIH [R15 grant number AA022496].

This research was supported in part by grants from R15 AA022496 to Aesoon Park.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement: No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Alegria M, Atkins M, Farmer E, Slaton E, Stelk W. One size does not fit all: Taking diversity, culture and context seriously. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2010;37(1):48–60. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0283-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins Rahshida. Instruments measuring perceived Racism/Racial discrimination: Review and critique of factor analytic techniques. International Journal of Health Services. 2014;44(4):711–34. doi: 10.2190/HS.44.4.c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes GM, Welte JW, Hoffman JH, Tidwell MO. Comparisons of gambling and alcohol use among college students and noncollege young people in the United States. Journal of American College Health. 2010;58(5):443–452. doi: 10.1080/07448480903540499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett Nancy P, Clerkin Elise M, Wood Mark, Monti Peter M, O'Leary Tevyaw Tracy, Corriveau Donald, Fingeret Allan, Kahler Christopher W. Description and predictors of positive and negative alcohol-related consequences in the first year of college. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2014;75(1):103–14. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C, Okuda M, Wright C, Hasin DS, Grant BF, Liu SM, Olfson M. Mental health of college students and their non–college attending peers: Results from the national epidemiologic study on alcohol and related conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2008;65(12):1429–1437. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.12.1429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blume AW, Lovato LV, Thyken BN, Denny N. The relationship of microaggressions with alcohol use and anxiety among ethnic minority college students in a historically White institution. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2012;18(10):45–54. doi: 10.1037/a0025457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boynton M, O'Hara R, Covault J, Scott D, Tennen H. A mediational model of racial discrimination and alcohol-related problems among African American college students. Journal on Studies of Alcohol and Drugs. 2014;75(2):228–234. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.228. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2014.75.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broman CL. Stress, race and substance use in college. College Student Journal. 2005;39(2):340–352. [Google Scholar]

- Broman CL. Perceived discrimination and alcohol use among black and white college students. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education. 2007;51(1):8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Brondolo Elizabeth, Brady ver Halen Nisha, Pencille Melissa, Beatty Danielle, Contrada Richard J. Coping with racism: A selective review of the literature and a theoretical and methodological critique. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;32(1):64–88. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9193-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TL, Parks GS, Zimmerman RS, Phillips CM. The role of religion in predicting adolescent alcohol use and problem drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62(5):696–705. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camatta CD, Nagoshi CT. Stress, depression, irrational beliefs, and alcohol use and problems in a college student sample. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1995;19(1):142–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chartier K, Caetano R. Ethnicity and health disparities in alcohol research. Alcohol Research & Health. 2010;33(1-2):152–160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R. Interethnic group and intraethnic group racism: Perceptions and coping in Black university students. Journal of Black Psychology. 2004;30(4):506–526. doi: 10.1177/0095798404268286. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R, Anderson NB, Clark VR, Williams DR. Racism as a stressor for African Americans: A biopsychosocial model. American Psychologist. 1999;54(10):805–816. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.10.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke N, Kim S, White HR, Jiao Y, Mun E. Associations between alcohol use and alcohol-related negative consequences among Black and White college men and women. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2013;74(4):521–531. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contrada RJ, Ashmore RD, Gary ML, Coups E, Egeth JD, Sewell A, Ewell K, Goyal TM. Measures of ethnicity-related stress: Psychometric properties, ethnic group differences, and associated with well-being. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2001;31(9):1775–1820. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2001.tb00205.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6(2):117–128. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.6.2.117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Krull JL, Agocha VB, Flanagan ME, Orcutt HK, Grabe S, Jackson M. Motivational pathways to alcohol use and abuse among Black and White adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117(3):485–501. doi: 10.1037/a0012592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox WM, Klinger E. A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1988;97(2):168–180. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.97.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton WW, Muntaner C, Smith C, Tien A, Ybarra M. Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale: Review and revision (CESD and CESD-R) In: Maruish ME, editor. The Use of Psychological Testing for Treatment Planning and Outcomes Assessment. 3rd. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2004. pp. 363–377. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller-Rowell Thomas E, Cogburn Courtney D, Brodish Amanda B, Peck Stephen C, Malanchuk Oksana, Eccles Jacquelynne S. Racial Discrimination and Substance Use: Longitudinal Associations and Identity Moderators. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2012;35(6):581–590. doi: 10.1007/s10865-011-9388-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greeley Janet, Oei Tian. Alcohol and Tension-Reduction. In: Leonard Kenneth E, Blane Howard T., editors. Psychological Theories of Drinking and Alcoholism. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 14–53. [Google Scholar]

- Grekin ER. Perceived racism and alcohol consequences among African American and Caucasian college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26(4):924–930. doi: 10.1037/a0029593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell Jules P, Merritt Marcellus M, Kalu Jimalee. Racism, stress, and disease. In: Jones Reginald., editor. African American Mental Health: Theory, Research, and Intervention. Cobb & Henry; 1998. pp. 247–280. [Google Scholar]

- Harrell Shelly P. A multidimensional conceptualization of racism-related stress: Implications for the well-being of people of color. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2000;70(1):42–57. doi: 10.1037/h0087722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Dovidio J. How does stigma “get under the skin”? The mediating role of emotion regulation. Psychological Science. 2009;20(10):1282–1289. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02441.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herd D. Predicting drinking problems among Black and White men: Results from a national survey. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 1994;55(1):61–71. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilbe Joseph M. Negative binomial regression. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Humara MJ, Sherman MF. Situational determinants of alcohol abuse among Caucasian and African-American college students. Addictive Behaviors. 1999;24(1):135–138. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4603(98)00053-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston Lloyd D, O'Malley Patrick M, Bachman Jerald G, Schulenberg John E. Volume I: Secondary School Students. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2006. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975-2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kranzler HR, Scott D, Tennen H, Feinn R, Williams C, Armeli S, Covault J. The 5-HTTLPR polymorphism moderates the effect of stressful life events on drinking behavior in college students of African descent. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 2012;159(5):484–490. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecci Len, MacLean Michael G, Croteau Nicole. Personal goals as predictors of college student drinking motives, alcohol use and related problems. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63(5):620–30. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden W. Development and initial validation of a life event scale for students. Canadian Journal of Counseling and Psychotherapy. 1984;18(3):106–110. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon David P, Lockwood Chondra M, Hoffman Jeanne M, West Stephen G, Sheets Virgil. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7(1):83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JK, Tuch SA, Roman PM. Problem drinking patterns among African Americans: The impacts of reports of discrimination, perceptions of prejudice, and “risky” coping strategies. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;44(3):408–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill Jennifer E, Wardell Jeffrey D, Read Jennifer P. Drinking motives in the prospective prediction of unique alcohol-related consequences in college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2014;75(1):93–102. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulia N, Ye Y, Greenfield TK, Zemore SE. Disparities in alcohol related problems among White, Black, and Hispanic Americans. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2009;33(4):654–662. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00880.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murry VM, Brown PA, Brody GH, Cutrona CE, Simons RL. Racial discrimination as a moderator of the links among stress, maternal psychological functioning, and family relationships. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63(4):915–926. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00915.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user's guide. 5th. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén and Muthén; 1998–2012. [Google Scholar]

- O'Hara RE, Armeli S, Scott DM, Covault J, Tennen H. Perceived racial discrimination and negative-mood-related drinking among African American college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2015;76(2):229–236. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Malley PM, Johnston LD. Epidemiology of alcohol and other drug use among American college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2002;63(2):23–39. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse AL, Carter RT, Evans SA, Walter RA. An exploratory examination of the associations among racial and ethnic discrimination, racial climate, and trauma-related symptoms in a college student population. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2010;57(3):255–263. doi: 10.1037/a0020040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher Kristopher J, Selig James P. Advantages of monte carlo confidence intervals for indirect effects. Communication Methods and Measures. 2012;6(2):77–98. doi: 10.1080/19312458.2012.679848. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Randolph Mary E, Torres Hector, Gore-Felton Cheryl, Lloyd Bronwyn, McGarvey Elizabeth L. Alcohol Use and Sexual Risk Behavior among College Students: Understanding Gender and Ethnic Differences. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2009;35(2):80–84. doi: 10.1080/00952990802585422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read Jennifer P, Colder Craig R, Merrill Jennifer E, Ouimette Paige, White Jacquelyn, Swartout Ashlyn. Trauma and posttraumatic stress symptoms predict alcohol and other drug consequence trajectories in the first year of college. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80(3):426–39. doi: 10.1037/a0028210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read Jennifer P, Wood Mark D, Kahler Christopher W, Maddock Jay E, Palfai Tibor P. Examining the role of drinking motives in college student alcohol use and problems. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17(1):13–23. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.17.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richman Laura S, Boynton Marcella H, Costanzo Philip, Banas Kasia. Interactive Effects of Discrimination and Racial Identity on Alcohol-Related Thoughts and Use. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 2013;35(4):396–407. [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Sheldon LA, Carey KB, Elliott JC, Garey L, Carey MP. Efficacy of alcohol interventions for first-year college students: A meta-analytic review of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2014;82(2):177–188. doi: 10.1037/a0035192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selig JP, Preacher KJ. Monte Carlo method for assessing mediation: An interactive tool for creating confidence intervals for indirect effects [Computer software] 2008 [Google Scholar]

- Sellers Robert M, Smith Mia A, Shelton J Nicole, Rowley Stephanie AJ, Chavous Tabbye M. Multidimensional Model of Racial Identity: A Reconceptualization of African American Racial Identity. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 1998;2(1):18–39. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0201_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siebert DC, Wilke DJ. High-risk drinking among young adults: The influence of race and college enrollment. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2007;33(6):843–850. doi: 10.1080/00952990701653834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedley BD, Myers HF, Harrell SP. Minority-status stresses and the college adjustment of ethnic minority freshmen. Journal of Higher Education. 1993;64(4):434–452. doi: 10.2307/2960051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith Kathryn Z, Smith Philip H, Grekin Emily R. Childhood sexual abuse, distress, and alcohol-related problems: Moderation by drinking to cope. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2014;28(2):532–537. doi: 10.1037/a0035381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten RZ, Allen JP, editors. Measuring alcohol consumption. Humana Press; 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell MB, Sobell LC, Klajner F, Pavan D, Basian E. The reliability of a timeline method for assessing normal drinker college students' recent drinking history: Utility for alcohol research. Addictive Behaviors. 1986;11(2):149–161. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(86)90040-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Summary of national findings (Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-38A, HHS Publication No SMA 10-4586) Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2010. Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Volume 1. Retrieved from http://www.samhsa.gov/data/NSDUH/2k9NSDUH/2k9Results.htm. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. Digest of Education Statistics, 2014. 2016 Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=98.

- Wallace JM, Jr, Muroff JR. Preventing substance abuse among African American children and youth: Race differences in risk factor exposure and vulnerability. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2002;22(3):235–261. doi: 10.1023/A:1013617721016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie EW. Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1989;50(1):30–37. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: evidence and needed research. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;32(1):20–47. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witbrodt Jane, Mulia Nina, Zemore Sarah E, Kerr William C. Racial/Ethnic disparities in Alcohol-Related problems: Differences by gender and level of heavy drinking. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2014;38(6):1662–70. doi: 10.1111/acer.12398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapolski Tamika CB, Pedersen Sarah L, McCarthy Denis M, Smith Gregory T. Less drinking, yet more problems: Understanding African American drinking and related problems. Psychological Bulletin. 2014;140(1):188–223. doi: 10.1037/a0032113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]