Abstract

YcfD from Escherichia coli is a homologue of the human ribosomal oxygenases NO66 and MINA53, which catalyse histidyl-hydroxylation of the 60S subunit and affect cellular proliferation (Ge et al., Nat Chem Biol 12:960–962, 2012). Bioinformatic analysis identified a potential homologue of ycfD in the thermophilic bacterium Rhodothermus marinus (ycfDRM). We describe studies on the characterization of ycfDRM, which is a functional 2OG oxygenase catalysing (2S,3R)-hydroxylation of the ribosomal protein uL16 at R82, and which is active at significantly higher temperatures than previously reported for any other 2OG oxygenase. Recombinant ycfDRM manifests high thermostability (Tm 84 °C) and activity at higher temperatures (Topt 55 °C) than ycfDEC (Tm 50.6 °C, Topt 40 °C). Mass spectrometric studies on purified R. marinus ribosomal proteins demonstrate a temperature-dependent variation in uL16 hydroxylation. Kinetic studies of oxygen dependence suggest that dioxygen availability can be a limiting factor for ycfDRM catalysis at high temperatures, consistent with incomplete uL16 hydroxylation observed in R. marinus cells. Overall, the results that extend the known range of ribosomal hydroxylation, reveal the potential for ycfD-catalysed hydroxylation to be regulated by temperature/dioxygen availability, and that thermophilic 2OG oxygenases are of interest from a biocatalytic perspective.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00792-018-1016-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Ribosomes, Translation, Protein synthesis, Hydroxylase, Dioxygenase, Post-translational modification, Oxygen/hypoxia sensing, Thermophilic enzyme

Introduction

Ferrous iron and 2-oxoglutarate (2OG)-dependent oxygenases (2OG oxygenases) are a ubiquitous enzyme superfamily that catalyses a wide range of oxidative reactions (Hausinger and Schofield 2015). Their biochemical roles are diverse and include the catalysis of steps in secondary metabolite biosynthesis in plants and microbes and the regulation of transcription in most, if not all, eukaryotes. In humans and other animals, 2OG oxygenases play a central role in coordinating the cellular and physiological responses to limiting oxygen levels (hypoxia) (Hausinger and Schofield 2015; Schofield and Ratcliffe 2004). In humans, the cellular activity of the transcription factor hypoxia inducible factor (HIF) prolyl-hydroxylases (PHDs or EGLNs) is limited by O2 availability; together with other properties, this is proposed to enable the PHDs to act as hypoxia sensors for the important HIF system (Ehrismann et al. 2007). HIF activity is also regulated via asparaginyl hydroxylation as catalysed by factor inhibiting HIF (FIH), which belongs to the Jumonji C (JmjC) family of 2OG oxygenases (Hewitson et al. 2003). However, the HIF pathway appears to be limited to animals (Loenarz et al. 2011); in microbes, other well-characterised mechanisms not involving 2OG oxygenases are established as hypoxia sensors (Taabazuing et al. 2014).

Intrigued by the similarity of FIH to apparent bacterial JmjC proteins, we recently identified Escherichia coli ycfD (ycfDEC) as an arginyl hydroxylase, which catalyses hydroxylation of R81 (homologous to R82 in R. marinus) in the E. coli 50S ribosomal protein uL16 (Ge et al. 2012) [ribosomal nomenclature is as according to Ban et al. (2014)]. R81 is located in the immediate vicinity of the peptidyl transferase centre and has been identified as one of the key uL16 residues that is involved in guiding A- to P-site tRNA translocation by facilitating ‘sliding’ and stepping’ mechanisms (Bock et al. 2013). YcfDEC was first identified as a 2OG oxygenase that catalyses hydroxylation of a prokaryotic ribosomal protein, i.e. uL16 in E. coli, and is proposed to have functions relating to effects on global translation and growth rates under limiting nutrient conditions (Ge et al. 2012). Mina53 and NO66 are human homologues of ycfDEC. Mina53 and NO66 are not arginyl hydroxylases, instead being histidyl hydroxylases acting on eL27 and uL2, respectively (Ge et al. 2012). We have also identified hydroxylation of small ribosomal subunit uS12 and release factor eRF1 proteins as regulatory for the accuracy of protein synthesis (Feng et al. 2014; Katz et al. 2014; Loenarz et al. 2014; Singleton et al. 2014) in organisms ranging from yeasts to humans. Thus, the ribosomal oxygenases have to date been found in bacteria and eukaryotes, including humans, though they appear not to be present in archaea (Chowdhury et al. 2014).

YcfD appears to be highly conserved in Proteobacteria, in particular Gammaproteobacteria. Whilst mostly absent from other bacterial phyla, phylogenetic studies of ycfD homologues identified a small number of putative ycfD-like 2OG oxygenases in the phylum Bacteroidetes, in particular in species Rhodothermus marinus and Salinibacter ruber (Ge et al. 2012); no homologues were found in other thermophilic phyla. To our knowledge, no extremophilic 2OG oxygenase has previously been reported. We were, therefore, interested to observe evidence for a putative 2OG oxygenase with high sequence homology to ycfD in the genome of R. marinus, which is a thermo- and halophilic obligate aerobe that was first isolated from submarine alkaline hot springs in Iceland (Alfredsson et al. 1988). Reports suggest that R. marinus can only grow in a narrow zone in the hot springs, defined by temperature, salt concentration, content of organic material and O2 availability (Bjornsdottir et al. 2006). The optimal growth temperature for R. marinus of 65 °C is significantly higher than those for other organisms with characterised 2OG oxygenases. This suggested that the operating temperature range for 2OG oxygenases could extend to temperatures of at least 65 °C, at least for thermophile-based enzymes, with potential biotechnological implications. We also proposed that ycfDRM may be more amenable to crystallographic analyses, in particular with respect to obtaining substrate complexes, than ycfDEC (Chowdhury et al. 2014). Here, we report studies on the biochemical characterization of ycfDRM; the results reveal ycfDRM is a bona fide 2OG oxygenase, the first characterised thermostable 2OG oxygenase. Furthermore, we propose that uL16 hydroxylation in cells may be limited by temperature and/or oxygen availability.

Materials and methods

Strains and growth conditions

Rhodothermus marinus (strain R-10 DSM 4252) was grown in ATCC Medium 1599 enhanced with NaCl (1% w/v) at 60–80 °C in an Innova44 (New Brunswick Scientific) shaking incubator either in unbaffled Pyrex® Erlenmeyer flasks (2 L, filled to 0.6 L), or Tunair™ polypropylene flasks (2.5 L, filled to 1 L), shaken at 180 rpm.

When cultures reached an OD600 0.9–1.0, the cells were harvested by centrifugation and stored at − 80 °C. The cell paste was lysed using glass beads in a PreCellys homogenizer (sonication was found to be insufficient for effective cell lysis). Ribosomal proteins were purified using a previously reported method (Hardy et al. 1969).

LC–MS studies on ribosomal proteins

Ribosomal proteins were analysed by reverse-phase ultra-performance liquid chromatography (RP-UPLC; Waters BEH C4 reversed phase column, 2.1 × 150 mm, 1.7 μm particle size, 300 Å pore size) and electrospray ionisation time-of-flight mass spectrometry (ESI-TOF MS). Proteins were separated using a stepped gradient 0.1% formic acid in water to 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile at 0.3 mL/min as described (Ge et al. 2012).

Cloning of ycfDRM

Rhodothermus marinus genomic DNA was isolated using a DNA isolation kit (DNEasy; Qiagen). The gene of interest (gi: 345301926) was amplified from genomic DNA using the following primers: forward CACAGCCACGACGTTTACC; reverse GGAATCACGTTGACCCAGTC. Amplification of the gene by polymerase chain reaction was carried out over 40 cycles at 96 °C for 30 s, 64 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 75 s, using Bio-X-Act Long DNA Taq polymerase (Bioline Ltd). The PCR product was ligated into the pGEMT-Easy vector (Promega) from which the ycfDRM gene was amplified with NdeI/SacI restriction sites using the primers ATAAACATATGCAGCTTCCCGA/AGAATAGAGCTCAGCGTTTGC and sub-cloned into pET28a using the NdeI/SacI restriction sites. YcfDRM protein was expressed using the pET28a vector system in E. coli strain BL21 (DE3). Protein was purified using a HisTrap HP column (5 mL, GE Healthcare) followed by Superdex 75 size-exclusion column (300 mL, GE Healthcare) using 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, and 5% glycerol as elution buffer.

Enzymatic activity studies

Enzymatic activity was determined using a MALDI–MS-based assay. Unless indicated otherwise, the enzyme was incubated at 55 °C with (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2 (100 μM), sodium ascorbate (1 mM), 2OG (200 μM) and a peptide fragment of R. marinus uL16 (uL16RM) corresponding to residues 72KPVTKKPAEVRMGKGKGSVE91 (GL Biochem, Shanghai, China, 100 μM) in 50 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.5). The reaction was quenched with an equal volume of 1% (v/v) aqueous CF3COOHaq and analysed by MALDI–MS. Substrate turnover was defined as %OH = IOH/(IOH + Inon-OH) × 100%, where IOH and Inon-OH correspond to peak intensities of hydroxylated and non-hydroxylated peptides, respectively.

To investigate the O2 dependence of the reaction, assays were performed at 37 °C in sealed vials which contained 500 µM peptide in the HEPES 50 mM, pH 7.5, buffer pre-equilibrated using mass-flow controllers (Brooks Instrument, UK) under N2/O2 gas mixes with variable O2 content (from 0 to 50%). Other components of the reaction were added using a Hamilton syringe prior to the assay, to final concentrations of 100 µM Fe(II), 1 mM l-ascorbate, 500 µM 2OG, 2 µM ycfDRM. The reaction was quenched with 1% (v/v) aqueous formic acid at defined time points. Substrate turnover was assessed by MALDI–TOF–MS as described above.

LC–MS/MS assays

LC–MS/MS experiments were performed using an Orbitrap Elite machine (Thermo Fisher Scientific, DE, USA) connected to a UHPLC Proxeon EASY-nLC 1000 and an EASY-Spray nano-electrospray ion source. Peptides were trapped on an Acclaim PepMap® trapping column (100 μm i.d. × 20 mm, 5 μm C18) and separated using an EASY-spray Acclaim PepMap® analytical column (75 μm i.d. × 500 mm, RSLC C18, 2 μm, 100 Å). MS method parameters are detailed in Supplementary Information.

Differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) studies

Thermostability of the enzyme was measured by differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) using a MiniOpticon Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). Fluorescence was measured between 4 and 95 °C, using FAM (492 nm) and RIOX (610 nm) excitation and emission filtres, respectively. The melting temperature (Tm) is calculated using the Boltzmann equation , where LL and UL are values of minimum and maximum intensities and a corresponds to the slope of the curve within Tm.

Circular dichroism (CD) studies

Circular dichroism measurements were acquired using a Chirascan CD spectrometer (Applied Photophysics) with a Peltier temperature-controlled cell holder. All experiments were performed in a 0.1-cm path length cuvette using 0.1–0.2 mg/mL protein in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 8.0). Data were recorded from 240 to 185 nm, at 0.5 nm intervals, and each data point was averaged for 3 s. Spectra were base-line corrected and smoothed using the Savitzky–Golay filtre. Data recorded in the 185–240 nm range were analysed using DichroWeb and the CONTIN deconvolution method was used to estimate secondary structural content using reference set 6 (Provencher and Glockner 1981; Vanstokkum et al. 1990). In thermal denaturation experiments, spectra were recorded every 2–5 °C, with a 5-min equilibration time at each temperature. Temperature-dependent changes in secondary structure were monitored by CD at 218 nm, and normalised data fit to a Boltzmann sigmoidal curve in GraphPad Prism to determine Tm values. At the end of the melt, reversibility was determined by returning to the start temperature (10 °C) and comparing the CD spectrum with the spectrum obtained prior to denaturation.

Amino acid analyses

Amino acid analyses were performed as previously described (Ge et al. 2012) with an enzymatic amino acid hydrolysis step performed as described (Feng et al. 2014).

Results

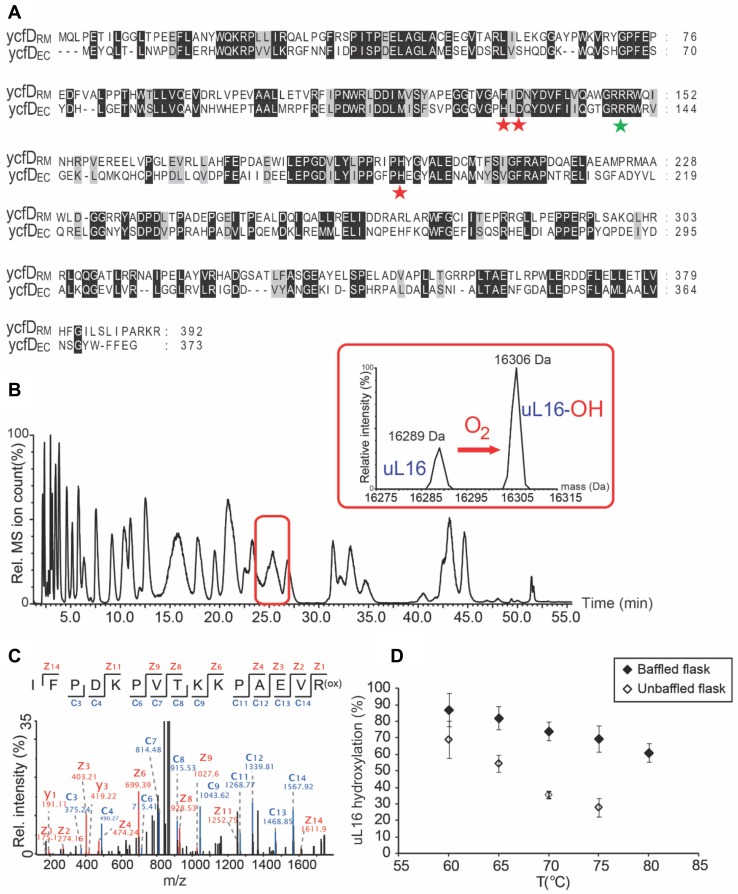

Bioinformatic analysis of ycfD homologues (Ge et al. 2012) identified a homologous protein from the thermo- and halophilic organism R. marinus (gi: 345301926), ycfDRM. YcfDRM has ~35% amino acid identity and ~55% similarity to ycfD from E. coli (ycfDEC, Fig. 1a). YcfDRM residues corresponding to the ycfDEC Fe(II)-coordinating triad are apparently conserved (ycfDRM H133, D135, H196), as is the basic residue (R148) that is predicted to bind the 2OG C-5 carboxylate (Fig. 1a). Because ycfDEC and its human homologues NO66 and MINA53 are ribosomal oxygenases, albeit with different target proteins and sequence selectivity (Ge et al. 2012), we proposed that ycfDRM might also modify ribosomal proteins.

Fig. 1.

ycfDRM from R. marinus catalyses oxygen-dependent ribosomal protein hydroxylation. a Protein sequence alignment of ycfDRM and ycfDEC produced with ClustalW and edited using GeneDoc 2.7. Red stars in a indicate the Fe(II)-binding facial triad and the green star indicates the basic residue that binds 2OG. b Ribosomal proteins were isolated by sucrose density centrifugation followed by acetone precipitation. UPLC protein separation coupled to ESI-TOF mass spectrometry was used to chromatographically separate and determine the intact masses of R. marinus ribosomal proteins. Inset: deconvoluted ESI–MS spectrum showing partial hydroxylation of ribosomal protein uL16RM. c MS/MS spectrum of uL16RM fragment showing hydroxylation at R82; d Hydroxylation of uL16RM decreases with an increase in growth temperature of R. marinus and varies for growth in baffled (2.5 L polypropylene filled to 1 L with media) and unbaffled flasks (2 L Pyrex filled to 0.6 L with media). uL16RM intact protein masses were determined by ESI–MS spectrometry. Average of two independent MS experiments is shown with error bars denoting standard deviation of the mean. Deconvoluted MS spectra are shown in Supplementary Materials

To study post-translational modifications of R. marinus ribosomal proteins, optimization of large-scale R. marinus growth was first conducted (see Supplementary Materials). Intact protein mass spectrometric analysis of R. marinus ribosomal proteins used a modification of our established UPLC–ESI–MS methodology (Ge et al. 2012); 48 out of 54 predicted ribosomal proteins in R. marinus were identified based on intact mass and their identity confirmed by MS/MS (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). Intact masses of several other proteins from the 30S and the 50S ribosomal subunits were consistent with post-translational modifications, as described in Supplementary Materials (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). Importantly, we observed two co-eluting species at retention time 25.3 min with masses 16,289 and 16,306 Da (Fig. 1b), consistent with unhydroxylated and hydroxylated uL16RM. uL16RM is also subject to monomethylation, presumably on its N-terminal methionine as occurs in E. coli (Arnold and Reilly 1999). MS–MS analysis of trypsin-digested ribosomal proteins identified the hydroxylation site on R82 (Fig. 1c), analogous to the E. coli uL16 (uL16EC) R81, which is the hydroxylation substrate of ycfDEC. Interestingly, we observed incomplete uL16RM hydroxylation (35%, Fig. 1d) at 70 °C, the optimal growth temperature of R. marinus. We cultured R. marinus between 60 and 75 °C and observed approximately linearly decreasing levels of uL16RM hydroxylation. uL16RM hydroxylation decreased from 60 to 25% as the growth temperature was increased from 60 to 75 °C. Hydroxylation of uL16RM was higher in baffled flasks compared to unbaffled flasks (Fig. 1d), consistent with previous reports that baffled flasks provide adequate oxygen supplies for microbial growth and that oxygen consumption in bacterial cultures is substantially higher in baffled flasks compared to unbaffled flasks under similar growth conditions (McDaniel and Bailey 1969). Collectively, these observations imply that uL16RM hydroxylation is sensitive to oxygen availability.

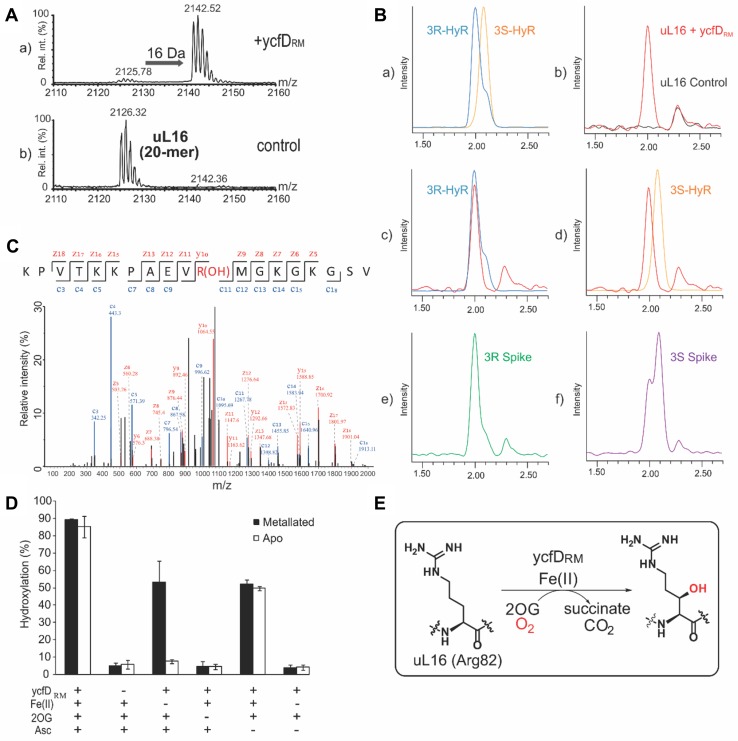

To investigate whether the observed hydroxylation of uL16RM is indeed catalysed by ycfDRM, we then focused on the biochemical characterization of ycfDRM in vitro. YcfDRM was recombinantly produced in E. coli using Ni(II)-affinity chromatography and size-exclusion chromatography. Upon incubation of the uL16RM peptide fragment (76KKPAEVRMGKGKGSVE91) with ycfDRM and co-factors/co-substrates Fe(II) and 2OG, a + 16 Da mass shift, consistent with hydroxylation, was observed by MALDI–MS, confirming ycfDRM as a bona fide 2OG oxygenase (Fig. 2a). MS/MS analysis of the hydroxylated peptide product confirmed the site of hydroxylation at residue R82 and amino acid analysis demonstrated (2S, 3R)-arginyl hydroxylation, thus having the same stereospecificity of hydroxylation as ycfDEC (Fig. 2b, c), supporting the assignment of ycfDRM as an arginyl hydroxylase of the ribosomal protein uL16RM. The catalytic activity of a ycfDRM iron-binding variant H133A, predicted to abrogate binding of Fe(II), was reduced to background levels, suggesting that Fe(II) binding is essential for catalytic activity (Supplementary Figure 1).

Fig. 2.

YcfDRM is a 2-oxoglutarate-dependent oxygenase. a MALDI–MS spectrum of ycfDRM-dependent hydroxylation of R. marinus uL16RM fragment (KPVTKKPAEVRMGKGKGSVE). A 16 Da mass shift is consistent with a ycfDRM-dependent oxidative modification. b Amino acid analysis reveals (2S, 3R)-hydroxylation of R82. Extracted ion chromatograms (m/z = 345) from LC–MS analysis of: a synthetic (2S, 3S)- and (2S, 3R)-3-hydroxy-arginine standards, b–d amino acid hydrolysates from ycfDRM-hydroxylated uL16RM peptide fragment(red trace) overlaid with hydrolysates from a control peptide (black trace, b), (2S, 3R)-hydroxy-arginine standard (blue trace, c) or (2S, 3S)-hydroxy-arginine standard (yellow trace, d); e–f amino acid hydrolysates from ycfDRM-hydroxylated uL16RM spiked with either (2S, 3R)-hydroxy-arginine (e) or (2S, 3S)-hydroxy-arginine (f) standards. c MS/MS studies on uL16RM fragment peptide (KPVTKKPAEVRMGKGKGSVE-NH2) incubated with ycfDRM and co-factors/co-substrates (Fe(II), 2OG and ascorbate) revealed hydroxylation at R82. d Co-factor dependence of ycfDRM:ycfDRM (1 μM) was incubated in a reaction mixture from which co-factors and co-substrates (Fe(II), 2OG and ascorbate at 100 μM, 200 μM and 1 mM, respectively), were systematically removed. Apo- and metallated forms of ycfDRM were tested. The reaction was carried out in 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5) at 65 °C in triplicates. The mean value is shown, with error bars representing standard deviation. e Reaction scheme of ycfDRM-catalysed (2S, 3R)-arginine-3-hydroxylation

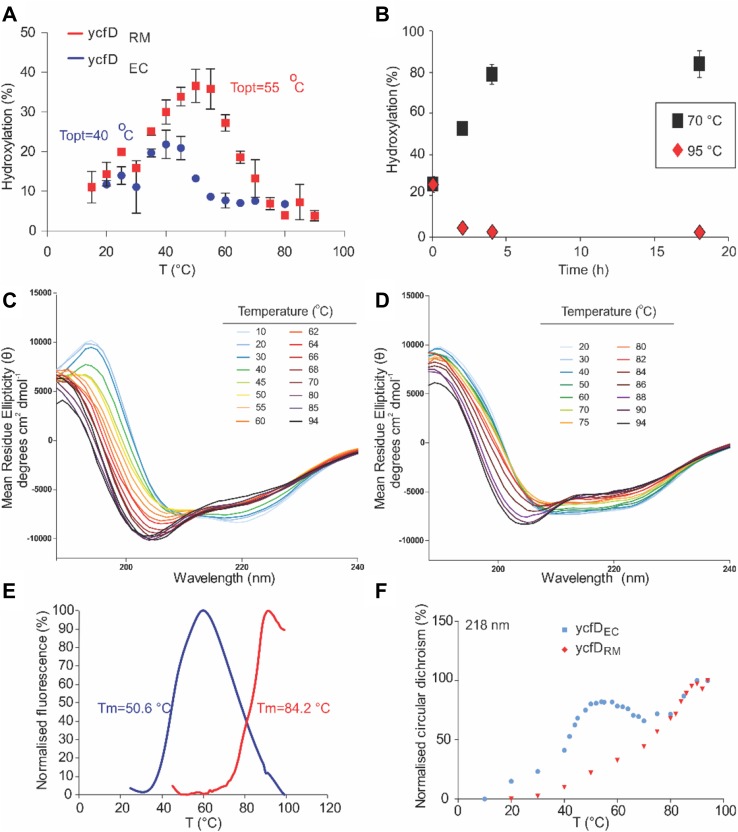

Next, we studied the biophysical properties of ycfDRM, compared to ycfDEC. We first studied the catalytic activity of ycfDRM and ycfDEC at different temperatures. YcfDRM maintained activity at higher temperatures than ycfDEC, demonstrating maximum catalytic activity (Topt) at 55 °C, compared to 40 °C for ycfDEC (Fig. 3a). YcfDRM catalytic activity (measured at Topt) was retained after incubation at 70 °C for up to 18 h, whereas incubation at 95 °C led to complete inactivation (Fig. 3b). To compare the thermal stabilities of ycfDRM and ycfDEC, their thermal denaturation was studied using circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy. We monitored temperature-induced changes in CD at 218 nm (characteristic wavelength for beta-sheet) and determined Tm values of 41 and 85 °C for ycfDEC and ycfDRM, respectively (Fig. 3c, d, f). Consistent with the CD measurements, an analogous study using differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) demonstrated a similar difference in Tm values: 51 °C compared to 84 °C for ycfDEC and ycfDRM, respectively (Fig. 3e).

Fig. 3.

Temperature dependence of ycfDEC/ycfDRM activity and stability. a ycfDEC and ycfDRM were incubated with E. coli and R. marinus uL16 fragment peptides, respectively, in the presence of co-factors/co-substrates (Fe(II), 2OG and ascorbate at 100 μM, 200 μM and 1 mM, respectively), in 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5 (ycfDRM) or pH 8.0 (ycfDEC). Reaction mixtures were incubated under atmospheric conditions at the indicated temperatures before addition of the enzyme (1 μM) and reaction allowed to proceed for 3 min before quenching with equal volume of CF3COOHaq (1%). Substrate turnover was determined by MALDI–MS. Reactions were carried out in triplicate, with points indicating the average and error bars denoting standard deviation. b Results of pre-incubation of ycfDRM at 70 °C (black squares) and 95 °C (red diamonds). Pre-incubation at 70 °C leads to increased activity; pre-incubation 95 °C leads to loss of catalytic activity. c, d Circular dichroism (CD) spectra of ycfDRM and ycfDEC between 20 and 94 °C. The CD signal was recorded between 190 and 260 nm while thermal denaturation was performed on ycfDRM and ycfDEC 20–94 °C. The signal at 218 nm was used to derive Tm values (f). A sigmoidal dose–response function was used to fit the data to derive the Tm value (GraphPad Prism, version 5.04, GraphPad Software). CD spectra of ycfDRM and ycfDEC thermal denaturation reveal a degree of denaturation above 80 °C with a retention of a significant degree of secondary structure up to 94 °C for ycfDRM, but not ycfDEC; e differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) was used to investigate the temperature dependence of ycfDEC/ycfDRM stability. Experiments were conducted in triplicate, with representative spectra shown

While Tm values are thus comparable to the optimal growth temperature of R. marinus, the observed difference in optimal temperature (Topt) for catalysis by isolated recombinant ycfDRM was > 15 °C below the optimal growth temperature of R. marinus. This observation may reflect non-optimal turnover conditions including the use of a fragment of the natural uL16RM protein substrate, which may lead to enhanced inactivation at higher temperatures in vitro due to uncoupling of 2OG and substrate oxidation (Hausinger and Schofield 2015). Steady-state kinetic analysis at 37 °C revealed that Kappm values for Fe(II) and 2OG (14.6 ± 5.4 and 71.1 ± 12.2 μM, respectively) were likely not limiting for the activity of ycfDRM. Both values were found to be higher than for ycfDEC, for which Kappm values for Fe(II) and 2OG were 3.3 ± 1.4 and 8.6 ± 3.4 μM, respectively (Supplementary Figure 2).

Interestingly, the Kappm of 100 ± 20 μM O2 (Supplementary Figure 3) for ycfDRM is in the range of O2 solubility at 70 °C [the calculated solubility of O2 at 70 °C and 3.5% (w/w) salinity is 128 μM according to the model of Tromans (1998)]. Oxygen availability could, therefore, limit the activity of ycfDRM in cells, consistent with our LC–MS studies on purified R. marinus ribosomes. The Kappm for ycfDEC was significantly lower than that for ycfDRM (Supplementary Figure 3), suggesting that oxygen availability is less likely to be limiting for ycfDEC activity, as is consistent with the observation of complete hydroxylation of uL16EC as reported elsewhere (Arnold and Reilly 1999; Ge et al. 2012).

The ycfD target residue (R81 in E. coli, R82 in R. marinus and T. thermophilus) is located at the apex of a flexible loop that protrudes into the peptidyl transferase centre (PTC) in the 50S subunit (Voorhees et al. 2009). We, therefore, proposed that the activity of ycfDRM with the short uL16RM fragment substrate may be reduced due to conformational mobility of a linear peptide fragment. We synthesised a cyclic peptide mimic of the uL16RM loop conformation to investigate whether a loop-like uL16RM fragment is a better substrate for ycfDRM (the synthesis is described in Supplementary Information). Guided by ribosome structures (when this work was carried out we did not have a ycfD substrate structure; Chowdhury et al. 2014), we designed a thioether-linked cyclic peptide (Supplementary Figure 4). In support of the subsequently obtained crystal structure for the ycfDRM–uL16RM complex (Chowdhury et al. 2014), the cyclic peptide was more efficiently hydroxylated than the acyclic peptide by ycfDRM (Supplementary Figure 4). Notably the Kappm for the synthetic cyclic uL16RM peptide (76KKPAEVRMGKGKG88-linker) was 75 ± 23 μM, compared to Kappm of 208 ± 66 μM for the linear variant (Supplementary Figure 4). The kcat value remained approximately constant (0.50 and 0.47 s−1 for linear and cyclic uL16 peptides, respectively), suggesting that the mechanism of hydroxylation is the same for the linear and cyclic variants, but that the pre-organisation of the cyclic peptide conformation better mimics the native conformation of uL16.

Discussion

YcfDEC is a 2OG- and Fe(II)-dependent oxygenase that catalyses arginyl hydroxylation of the ribosomal protein uL16EC, a modification linked to the overall rate of protein biosynthesis and cell growth (Ge et al. 2012). Human orthologues of ycfD, NO66 and MINA53 also catalyse ribosomal protein hydroxylation of eukaryotic ribosomal proteins from the large subunit, but of histidinyl rather than arginyl residues (Ge et al. 2012) (Chowdhury et al. 2014). The ycfD/NO66/MINA53 family is, therefore, evolutionarily and functionally conserved from prokaryotes to mammalians.

We identified a gene with high sequence similarity to ycfDEC in R. marinus from the phylum Bacteroidetes. R. marinus is found in shallow alkaline hot springs where temperatures exceed 70 °C (Alfredsson et al. 1988). Given the diverse range of stereospecific oxidative modifications that 2OG oxygenases catalyse, including activation of unactivated C-H bonds (Hausinger and Schofield 2015; Martinez and Hausinger 2015), which is otherwise synthetically challenging (Hartwig 2016), their biocatalytic potential is substantial. The results presented here define ycfDRM as a thermophilic 2OG oxygenase that, by analogy with ycfDEC (Ge et al. 2012), likely functions as a hydroxylase of the ribosomal protein uL16RM. They thus expand the scope of ribosomal hydroxylation, and of 2OG oxygenase catalysis, to extremophilic organisms. The demonstration that it is possible to use purified thermostable recombinant 2OG oxygenases is of substantial interest from a biocatalytic perspective, in part because although (engineered) 2OG oxygenases are used for biocatalysis in cells, their lability appears to have precluded their widespread use in purified form.

Intact protein mass spectrometric analysis of ribosomal proteins from R. marinus revealed two species of 16289 ± 1 and 16306 ± 1 Da, consistent with masses of unhydroxylated and hydroxylated uL16RM. MS/MS analysis of uL16RM identified the modification as hydroxylation of R82. We reasoned that the oxidative modification may be catalysed by the ycfD homologue identified in R. marinus genome. We cloned, expressed and purified ycfDRM and studied its biochemical properties. YcfDRM was found to be Fe(II), 2OG and O2 dependent, thus classifying it as a bona fide 2OG oxygenase.

Importantly, from the biocatalytic perspective, we demonstrated that ycfDRM is more thermostable than ycfDEC from E. coli (Tm of 84 vs. 51 °C) and, to our knowledge, any other characterised 2OG oxygenase, and with higher degree of catalytic turnover at 55–60 °C (compared to 45 °C for ycfDEC). The difference in Tm between ycfDEC and ycfDRM is characteristic of thermophilic adaptation of protein structure. Thermophilic proteins are frequently adapted for stability, but not necessarily activity, at high temperature, often by introduction of rigidifying salt-bridge interactions (Lam et al. 2011). Indeed, a comparison of primary structures of ycfDRM and ycfDEC (Fig. 1a) reveals a relative increase in highly charged, or rigidifying amino acids (relative abundance of Arg, Glu, Pro is increased by 4, 2 and 1%, respectively) and a decrease in residues with less-concentrated charge (relative abundance of Ser, Asp, Asn and Gln is decreased by 2, 3, 3 and 1%, respectively) in ycfDRM, compared to mesophilic ycfDEC.

Intact protein MS analysis revealed that uL16RM hydroxylation levels decrease with increasing temperature. We, therefore, investigated what factors may limit the catalytic activity of ycfDRM. The results of thermal denaturation experiments, including DSF and CD, as well as MALDI–MS-based kinetic assays indicate that protein stability, as well as Fe(II) and 2OG availability (at least in vitro), are not likely to be limiting factors in ycfDRM activity, even at relatively high temperatures.

We, therefore, addressed the dependence of ycfDRM on molecular oxygen. With the caveat that we used a uL16RM peptide fragment (20-mer) rather than intact protein, it is notable that the Kappm (O2) for ycfDRM was 100 ± 20 μM. The Kappm for O2 is, therefore, apparently in the range of oxygen solubility limits (Tromans 1998). The rate of ycfDRM catalysis is apparently linearly dependent on O2 availability; therefore, slight changes in O2 concentration will likely result in changes in ycfDRM activity. This observation is consistent with the temperature-dependent linear decrease in levels of uL16RM hydroxylation observed between 60 and 75 °C in R. marinus cells (Fig. 1d). Thus, O2-regulated changes in ycfDRM-catalysed uL16 hydroxylation have potential to be biologically relevant, potentially in a hypoxia sensing capacity. The latter is a possibility of interest given the roles of 2OG oxygenases in hypoxia sensing by animals (Hausinger and Schofield 2015; Schofield and Ratcliffe 2004). Interestingly, uL16 hydroxylation in E. coli is > 95% at 37 °C, the optimal growth temperature for this organism (Ge et al. 2012).

The identification of ycfDRM as 2OG dependent extends the known range of these ubiquitous enzymes. The observation of its variable activity in cells raises the possibility that uL16 hydroxylation has a signalling or regulatory role. It is notable that hydroxylated ribosomal protein residue R82 on uL16 has been described as crucial for the process of translocation during peptidyl transfer (Bock et al. 2013), and that ycfD knock-out in E. coli, devoid of uL16 hydroxylation, leads to a lower rate of peptide synthesis (Ge et al. 2012). Future research can focus on further studies employing genetic methods to study the roles of ycfDRM and uL16 hydroxylation in vivo in R. marinus, and more generally on the importance of ribosome hydroxylation and its possible roles in the regulation of protein synthesis, including at high temperatures and, potentially, in a hypoxia sensing capacity.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Ian Clifton, Dr. Rashed Chowdhury and Dr. Louise Walport for helpful discussions. We thank the EPSRC, BBSRC, Wellcome Trust, Cancer Research UK, and the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts for financial support.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00792-018-1016-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- Alfredsson GA, Kristjansson JK, Hjorleifsdottir S, Stetter KO. Rhodothermus marinus, gen-nov, sp-nov, a thermophilic, halophilic bacterium from submarine hot springs in Iceland. J Gen Microbiol. 1988;134:299–306. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold RJ, Reilly JP. Observation of Escherichia coli ribosomal proteins and their posttranslational modifications by mass spectrometry. Anal Biochem. 1999;1:105–112. doi: 10.1006/abio.1998.3077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ban N, et al. A new system for naming ribosomal proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2014;24:165–169. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjornsdottir SH, et al. Rhodothermus marinus: physiology and molecular biology. Extremophiles. 2006;1:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s00792-005-0466-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock LV, et al. Energy barriers and driving forces in tRNA translocation through the ribosome. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;12:1390–1396. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury R, et al. Ribosomal oxygenases are structurally conserved from prokaryotes to humans. Nature. 2014;7505:422–426. doi: 10.1038/nature13263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrismann D, et al. Studies on the activity of the hypoxia-inducible-factor hydroxylases using an oxygen consumption assay. Biochem J. 2007;1:227–234. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng T, et al. Optimal translational termination requires C4 lysyl hydroxylation of eRF1. Mol Cell. 2014;4:645–654. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge W, et al. Oxygenase-catalyzed ribosome hydroxylation occurs in prokaryotes and humans. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;12:960–962. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy SJ, Kurland CG, Voynow P, Mora G. The ribosomal proteins of Escherichia coli. I. Purification of the 30S ribosomal proteins. Biochemistry. 1969;7:2897–2905. doi: 10.1021/bi00835a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartwig JF. Evolution of C–H bond functionalization from methane to methodology. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;1:2–24. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b08707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausinger R, Schofield C. 2-Oxoglutarate-dependent oxygenases. Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry; 2015. p. 487. [Google Scholar]

- Hewitson KS, McNeill LA, Elkins JM, Schofield CJ. The role of iron and 2-oxoglutarate oxygenases in signalling. Biochem Soc Trans. 2003;Pt 3:510–515. doi: 10.1042/bst0310510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz MJ, et al. Sudestada1, a Drosophila ribosomal prolyl-hydroxylase required for mRNA translation, cell homeostasis, and organ growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;11:4025–4030. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314485111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam SY, Yeung RC, Yu TH, Sze KH, Wong KB. A rigidifying salt-bridge favors the activity of thermophilic enzyme at high temperatures at the expense of low-temperature activity. PLoS Biol. 2011;3:e1001027. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loenarz C, et al. The hypoxia-inducible transcription factor pathway regulates oxygen sensing in the simplest animal, Trichoplax adhaerens. EMBO Rep. 2011;1:63–70. doi: 10.1038/embor.2010.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loenarz C, et al. Hydroxylation of the eukaryotic ribosomal decoding center affects translational accuracy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;11:4019–4024. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311750111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez S, Hausinger RP. Catalytic mechanisms of Fe(II)- and 2-oxoglutarate-dependent oxygenases. J Biol Chem. 2015;34:20702–20711. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R115.648691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel LE, Bailey EG. Effect of shaking speed and type of closure on shake flask cultures. Appl Microbiol. 1969;2:286–290. doi: 10.1128/am.17.2.286-290.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provencher SW, Glockner J. Estimation of globular protein secondary structure from circular-dichroism. Biochemistry. 1981;1:33–37. doi: 10.1021/bi00504a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield CJ, Ratcliffe PJ. Oxygen sensing by HIF hydroxylases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:343–354. doi: 10.1038/nrm1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton RS, et al. OGFOD1 catalyzes prolyl hydroxylation of RPS23 and is involved in translation control and stress granule formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;11:4031–4036. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314482111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taabazuing CY, Hangasky JA, Knapp MJ. Oxygen sensing strategies in mammals and bacteria. J Inorg Biochem. 2014;133:63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2013.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tromans D. Temperature and pressure dependent solubility of oxygen in water: a thermodynamic analysis. Hydrometallurgy. 1998;3:327–342. doi: 10.1016/S0304-386X(98)00007-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vanstokkum IHM, Spoelder HJW, Bloemendal M, Vangrondelle R, Groen FCA. Estimation of protein secondary structure and error analysis from circular-dichroism spectra. Anal Biochem. 1990;1:110–118. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(90)90396-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voorhees RM, Weixlbaumer A, Loakes D, Kelley AC, Ramakrishnan V. Insights into substrate stabilization from snapshots of the peptidyl transferase center of the intact 70S ribosome. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;5:528–533. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.