Abstract

Background

Physician ratings websites have emerged as a novel forum for consumers to comment on their health care experiences. Little is known about such ratings in Canada.

Objective

We investigated the scope and trends for specialty, geographic region, and time for online physician ratings in Canada using a national data source from the country’s leading physician-rating website.

Methods

This observational retrospective study used online ratings data from Canadian physicians (January 2005-September 2013; N=640,603). For specialty, province, and year of rating, we assessed whether physicians were likely to be rated favorably by using the proportion of ratings greater than the overall median rating.

Results

In total, 57,412 unique physicians had 640,603 individual ratings. Overall, ratings were positive (mean 3.9, SD 1.3). On average, each physician had 11.2 (SD 10.1) ratings. By comparing specialties with Canadian Institute of Health Information physician population numbers over our study period, we inferred that certain specialties (obstetrics and gynecology, family practice, surgery, and dermatology) were more commonly rated, whereas others (pathology, radiology, genetics, and anesthesia) were less represented. Ratings varied by specialty; cardiac surgery, nephrology, genetics, and radiology were more likely to be rated in the top 50th percentile, whereas addiction medicine, dermatology, neurology, and psychiatry were more often rated in the lower 50th percentile of ratings. Regarding geographic practice location, ratings were more likely to be favorable for physicians practicing in eastern provinces compared with western and central Canada. Regarding year, the absolute number of ratings peaked in 2007 before stabilizing and decreasing by 2013. Moreover, ratings were most likely to be positive in 2007 and again in 2013.

Conclusions

Physician-rating websites are a relatively novel source of provider-level patient satisfaction and are a valuable source of the patient experience. It is important to understand the breadth and scope of such ratings, particularly regarding specialty, geographic practice location, and changes over time.

Keywords: quality improvement, patient satisfaction, patient-centered care, online ratings

Introduction

Patients’ abilities to discern health care quality are often underappreciated, despite evidence that low patient satisfaction scores and complaints against physicians are linked to increased risk management episodes, malpractice lawsuits, readmission rates, and even increased mortality for selected diagnoses [1-5]. Over the last decade, physician-rating websites have become a popular source of patient satisfaction data [6]. Such websites represent unsolicited reflections of the patient experience with their physicians in comparison to more traditional methods such as surveys. In the United States, the use of physician-rating websites is rapidly increasing, whereas other countries have reported more moderate growth [6,7]. In addition to private online physician websites, government or health insurer-developed sites are also being used in countries such as the United Kingdom and Germany [8,9]. Together, these physician-rating websites may impact patient health care decision making, as data suggests approximately one-third of users have searched for physicians online and report making decisions regarding physician selection based on these ratings [10]. Online physician-rating websites may also impact physician behaviors; over the last five years, physicians have been increasingly responding online to their ratings [11]. Hence, this data source may have significant implications on health care practice and behavior.

Most previous work on online physician ratings has focused on reviewing the frequency and usage among different physician specialties in the United States, China, and Germany [6,12-26], as well as exploring awareness and perceptions among physicians and consumers [10,11,27-29]. More recently, the focus has been to correlate online ratings with quality outcomes or surrogates such as postoperative mortality and surgical volumes with variable findings, depending on the quality outcome in question [6,30-38]. It has been estimated that one in six physicians are rated online, and most ratings are positive [6,12-4,17-19,28]. Although the use of physician-rating websites is increasing overall [6,7,39], for frequency of ratings, US studies have reported that the mean number of ratings per physician is low overall, ranging from two to four ratings per physician [6,17,21]. Several studies have focused on differences in ratings according to specialties [6,14,20-22]. Certain types of physicians, such as obstetricians, dermatologists, surgeons, and family physicians, are more frequently rated than other specialists. Board-certified, younger physicians have been shown to be rated more favorably than non-board-certified, younger physicians [6,14]. Other studies have investigated the relationship between practice location (such as city size) and online ratings. In the United States, physicians in the southern states had a higher likelihood of positive ratings than other parts of the country, whereas others have shown no difference in ratings with respect to practice location and city size [6,20-22].

In Canada, there is currently little information available on the use of physician-rating websites. Our study sought to investigate the nature and trends of online physician ratings in Canada over a nearly 8-year period. The goals of this study were to (1) determine whether online ratings for physicians differed depending on physician specialty, (2) investigate whether physician practice location affected online ratings, and (3) examine possible trends in ratings over time by year of rating. We also compared the number and frequency of ratings by specialty to determine whether certain specialties were rated online more frequently than expected based on their representation in the overall physician population. Based on previous studies, we hypothesized that certain specialties, such as obstetrics and family medicine, would be rated more frequently than others, such as pathology or radiology. We also felt that the quality of ratings would be positive overall and that differences in ratings would exist across specialties and geographic practice location. We suspected that there would be no differences in quality of ratings over time, but that the absolute number of ratings would be steadily increasing over our study period.

Methods

Overview

We accessed a national database of all Canadian physicians rated from January 2005 to September 2013 (N=640,603 ratings) [40]. RateMDs was founded in the United States in 2004 and is currently among the most popular physician-rating websites in Canada and the United States by user traffic [13,18]. No registration or subscription is required to view or post a rating, and there are no incentives to rate a physician. Physicians are rated on a scale of 1 to 5 (described by the website as 1=“terrible,” 2=“poor,” 3=“okay,” 4=“good,” 5=“excellent”). Ratings were given for each of the following domains: staff, punctuality, helpfulness, and knowledge. A mean overall score is posted for each physician. Physician profiles are created or searched for by the rater, and users provide ratings and may provide free-text comments if desired. Our dataset included deidentified data for 57,412 physicians, including specialty, practice region (city and province), date of rating, and scores on each of four domains, from which we calculated an average cumulative rating for each physician. This dataset included all physicians in Canada who were rated on RateMDs during our study period.

Mean number of ratings and mean ratings were calculated for all physicians, each website specialty, and province. To compare the relative proportions of physicians by specialty, we grouped specialties according to Canadian Institute of Health Information (CIHI) categories [41]. We considered “obstetrics and gynecology” as distinct from “surgery” because previous research demonstrated high numbers of ratings for this group [6,14]. We calculated each physician specialty’s online presence by grouping online specialties into CIHI specialty categorizations and divided the number of physicians rated online for that specialty by the total number of physicians in the online database. We then calculated and compared these values to the mean annual number of physicians divided by the total annual physician population for CIHI specialties from 2005 to 2013 (to match our online ratings data period). This allowed us to infer whether a specialty was rated more or less frequently than expected based on the mean annual physician population for that specialty.

Statistics

For statistical analysis, our objective was to recognize and compare differences in favorable versus unfavorable ratings for physician specialty, geographic practice location, and year of rating. We constructed a binary variable indicating whether each rating was greater than, less than, or equal to the median rating, which was 4.5 out of 5. We thus considered whether ratings were in the top 50th percentile of all ratings for one of three predictors: physician specialty, province, and year. For each level of predictor, the proportion of ratings greater than 4.5 was reported with a 95% confidence interval and a P value against the null hypothesis that the true proportion was equal to 0.5. In this way, we were able to stratify specialties, practice location by province, and year of rating according to likelihood of positive ratings. All analyses were performed using prop.test in R version 3.0.2.

Ethics

When submitting research ethics board approval, we were informed that the requirement for ethics approval was waived because data were publicly available.

Results

Findings

From February 2005 to September 2013, there were 640,603 ratings for 57,412 unique physicians. Ratings were generally positive (mean 3.9, SD 1.3). Using the online rating website’s rating descriptions, this translated to a mean rating that fell between “okay” and “good.” The mean number of ratings per physician was 11.2 (SD 10.1; see Table 1). During our study period, the mean annual number of total physicians in Canada was 66,026.1 (SD 5748.2). The largest group of physicians, by medical specialty, was family medicine/general practice (n=30,818 physicians). This group had 370,972 unique ratings and, on average, had 12 ratings per physician, with a mean overall rating of 3.9 (SD 1.3). Internal medicine (including its subspecialties) accounted for 53,818 total ratings of 6677 individual physicians, with 8.1 ratings per physician (SD 7.7) and a mean rating of 3.98 (SD 1.31) out of 5. Surgery (including its subspecialties) included 22,811 total ratings of 2472 individual physicians, with 11.9 ratings per physician (SD 10.7) and an overall mean rating of 4.01 (SD 1.32) out of 5. We found that certain specialties had relatively increased numbers of per-physician ratings, including reproductive endocrinology (mean 19.7, SD 15.2), cosmetics/plastic surgery (mean 16.7, SD 16.1), and obstetrics and gynecology (mean 17.6, SD 16.1). Additionally, certain medical specialties had lower numbers of rated physicians as well as per-physician ratings, including radiologists (total number of rated physicians: 330, mean per-physician ratings 3.0, SD 2.8), pathologists (total number of rated physicians: 13, mean per-physician ratings 4.4, SD 8.1), and medical geneticists (total number of rated physicians: 26, mean per-physician ratings 2.6, SD 4.9; see Table 1).

Table 1.

Number of ratings, unique number of physicians, and descriptive statistics and relative proportions of rated physicians grouped by Canada Institute of Health Information (CIHI) specialty (2005-2013).

| Medical specialty | Ratings, n | Unique rated physicians, n |

Ratings per physician, mean (SD) |

Overall rating, mean (SD) |

Annual physician populationa (%), mean (SD) |

% of online cohort |

% of mean annual physician populationb |

|||||||||

| Family medicine | 370,972 | 30,818 | 12.0 (9.7) | 3.9 (1.3) | 33,180.0 (4745.8) | 53.7 | 45.2 | |||||||||

| Internal medicine | 53,818 | 6677 | 8.1 (7.7) | 4.0 (1.3) | 7528.1 (778.3) | 12.0 | 10.3 | |||||||||

| Allergy/immunologist | 2690 | 235 | 11.5 (9.6) | 3.8 (1.3) | ||||||||||||

| Cardiologist | 8192 | 1278 | 6.4 (5.8) | 4.20 (1.2) | ||||||||||||

| Colorectal/proctologist | 312 | 36 | 8.7 (9.5) | 4.02 (1.4) | ||||||||||||

| Gastroenterologist | 9395 | 854 | 11.0 (8.8) | 3.91 (1.3) | ||||||||||||

| Endocrinologist | 5670 | 563 | 10.1 (8.6) | 3.81 (1.3) | ||||||||||||

| Reproductive endocrinologist | 1418 | 72 | 19.7 (15.2) | 3.91 (1.3) | ||||||||||||

| Geriatrician | 678 | 168 | 4.0 (4.4) | 3.84 (1.4) | ||||||||||||

| Infectious disease | 1074 | 199 | 5.4 (6.1) | 4.04 (1.3) | ||||||||||||

| Internist | 7045 | 1112 | 6.3 (6.4) | 3.90 (1.4) | ||||||||||||

| Nephrologist | 1868 | 364 | 5.1 (4.4) | 4.36 (1.1) | ||||||||||||

| Oncology/hematologist | 7038 | 1086 | 6.5 (6.1) | 4.12 (1.2) | ||||||||||||

| Pulmonologist | 2463 | 383 | 6.4 (5.8) | 4.10 (1.3) | ||||||||||||

| Rheumatologist | 5915 | 472 | 12.5 (9.4) | 3.81 (1.4) | ||||||||||||

| Sleep disorders | 371 | 57 | 6.5 (6.9) | 3.7 (1.4) | ||||||||||||

| Anesthesia | 2589 | 622 | 4.16 (5.0) | 4.14 (1.3) | 2713.1 (287.0) | 1.1 | 4.1 | |||||||||

| Obstetrics and gynecology | 43,627 | 2472 | 17.6 (15.0) | 3.88 (1.3) | 1709.0 (292.3) | 4.3 | 2.5 | |||||||||

| Surgery | 98,045 | 8235 | 11.9 (10.7) | 4.01 (1.3) | 6618.2 (375.3) | 14.3 | 10.0 | |||||||||

| Surgeon (general) | 22,811 | 2185 | 10.4 (9.1) | 4.16 (1.3) | ||||||||||||

| Cardiothoracic surgeon | 1954 | 202 | 9.6 (7.8) | 4.54 (1.0) | ||||||||||||

| Cosmetic/plastics | 13,226 | 793 | 16.7 (16.1) | 4.05 (1.3) | ||||||||||||

| Otolaryngology | 10,064 | 736 | 13.6 (11.4) | 3.87 (1.4) | ||||||||||||

| Neurosurgeon | 4686 | 363 | 12.9 (10.7) | 4.17 (1.3) | ||||||||||||

| Ophthalmologist | 12,419 | 1305 | 9.5 (8.5) | 3.90 (1.3) | ||||||||||||

| Orthopedics/sport | 22,492 | 1770 | 12.7 (10.0) | 3.91 (1.4) | ||||||||||||

| Bariatric/weight loss | 346 | 26 | 13.3 (30.5) | 4.05 (1.4) | ||||||||||||

| Urologist | 9655 | 772 | 12.5 (9.5) | 4.00 (1.3) | ||||||||||||

| Vascular surgeon | 392 | 83 | 4.7 (5.0) | 4.13 (1.4) | ||||||||||||

| Neurology | 9504 | 944 | 10.1 (9.5) | 3.59 (1.4) | 829.2 (83.1) | 1.6 | 1.2 | |||||||||

| Pediatrics | 20,751 | 1767 | 11.7 (10.7) | 4.1 (1.2) | 2488.0 (508.9) | 3.1 | 3.8 | |||||||||

| Radiology | 1005 | 330 | 3.0 (2.8) | 4.18 (1.3) | 2153.7 (216.2) | 0.6 | 3.3 | |||||||||

| Emergency/critical carec | 7716 | 1404 | 5.5 (5.4) | 3.81 (1.5) | 860.2 (260.0) | 2.4 | 1.1 | |||||||||

| Psychiatry | 18,036 | 2853 | 6.3 (6.4) | 3.55 (1.5) | 4218.9 (550.5) | 5.0 | 6.3 | |||||||||

| Psychiatry (general) | 17,695 | 2784 | 6.4 (6.4) | 3.55 (1.5) | ||||||||||||

| Addiction medicine | 341 | 69 | 4.9 (5.6) | 3.49 (1.5) | ||||||||||||

| Dermatology | 11,587 | 705 | 16.4 (14.9) | 3.53 (1.4) | 540.0 (27.0) | 1.2 | 0.8 | |||||||||

| Pathology | 57 | 13 | 4.4 (8.1) | 4.18 (1.2) | 1271.4 (100.1) | <0.01 | 1.9 | |||||||||

| Genetics | 68 | 26 | 2.6 (4.9) | 4.61 (0.8) | 75.8 (12.6) | <0.01 | <0.01 | |||||||||

| Physical medicine/rehabilitation | 2517 | 344 | 7.3 (8.3) | 3.71 (1.5) | 372.3 (41.2) | 0.6 | 0.6 | |||||||||

| Totals/means (SD) | 640,603 | 57,412 | 11.2 (10.1) | 3.9 (1.3) | 66,026.1 (5748.2) | |||||||||||

aFor each specialty, number of unique physicians rated online per total number of unique physicians rated online, expressed as a percent.

bFor each CIHI physician specialty, mean annual number of physicians per mean total number of annual physicians (2005-2013) expressed as a percent.

cEmergency/critical care, as a grouped CIHI specialty, was only available for the years 2009-2013; therefore, annual means were calculated over 5 years only for this specialty.

Differences in Frequencies of Ratings According to Specialty

For each specialty, we calculated the percentage of physicians with online ratings divided by the total online physician population, and compared it to the percentage of physicians in a given specialty divided by the total annual physician populations for CIHI specialties. Certain specialties were more frequently rated than expected based on their proportion in the national population, notably obstetrics and gynecology (4.3% of online cohort vs 2.5% of mean total annual obstetrics and gynecology population), dermatology (1.2% vs 0.8%), family practice (53.7% vs 45.2%), internal medicine (including its subspecialties; 12.0% vs 10.3%), emergency medicine/critical care (2.4% vs 1.1%), and surgery (14.3% vs 10.0%), whereas others were less represented, including anesthesia (1.4% vs 4.1%), radiology (0.6% vs 3.3%), psychiatry (5.0% vs 6.3%), and pathology (<0.01% vs 1.9%; see Table 1).

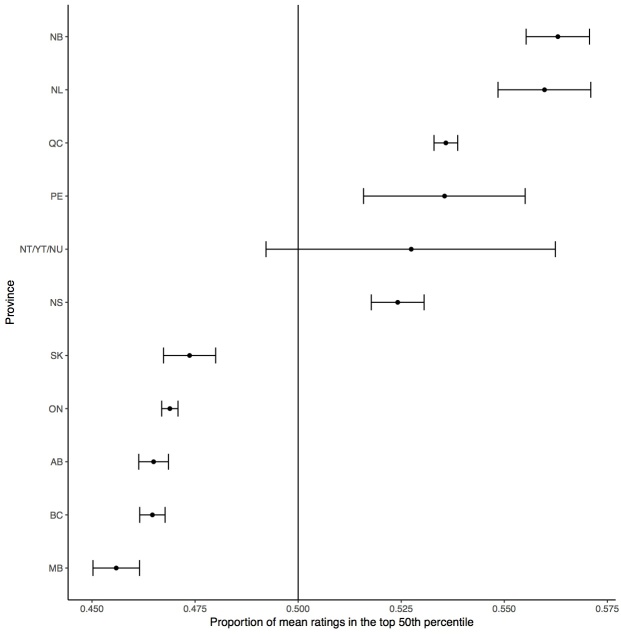

Differences in Quality of Ratings for Physician Specialty

We investigated whether there were differences in the quality of ratings depending on physician specialty. We found that ratings for certain specialties were more likely to be in the top 50th percentile of all ratings, including cardiac surgery (probability of a rating greater than the median of 4.5 was 78.1%, P<.001), genetics (73.5%, P<.001), nephrology (69.2%, P<.001), radiology (65.3%, P<.001), and vascular surgery (65.1%, P<.001). The bottom four physician specialties included psychiatry (42.2%, P<.001), neurology (42.1%, P<.001), dermatology (37.0%, P<.001), and addiction medicine (35.8%, P<.001; Figure 1; Multimedia Appendix 1). Family medicine/general practice comprised our largest group of physicians in the online cohort, as well as one of the largest groups of physicians represented in the mean annual physician population. Regarding likelihood of a favorable rating, family medicine/general practice was among the bottom seven physician specialties (46.3%, P<.001; Figure 1; Multimedia Appendix 1).

Figure 1.

Proportion of mean ratings, by specialty, in the top 50th percentile of all rated physicians (2005-2013) with 95% confidence intervals depicted for each proportion.

Differences in Frequency of Ratings for Physician Practice Location (by Province)

We found that Ontario had both the highest number of ratings and the highest number of rated unique physicians (244,635 ratings for 20,740 physicians), followed by Quebec (116, 041 for 13,460 physicians), then British Columbia (101,152 ratings for 8398 physicians). The lowest number of ratings for the lowest number of physicians was found in the less densely populated regions of the Northwest Territories/Yukon/Nunavut (802 ratings for 126 physicians) and Prince Edward Island (2534 ratings for 242 physicians).

For most provinces, per-physician number of ratings ranged from 10 to 13, with the exception of Quebec and the Northwest Territories/Yukon/Nunavut (ratings per physician 8.62 and 6.37, respectively).

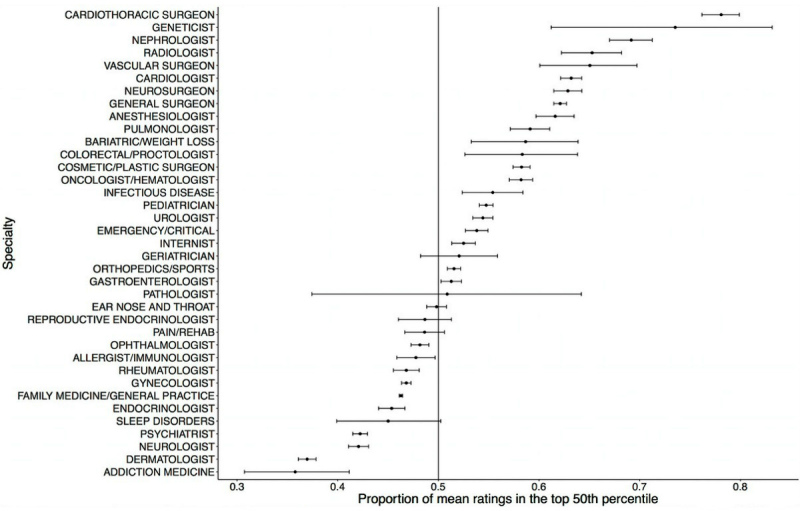

Differences in Quality of Ratings for Physician Practice Location (by Province)

We also found differences in a physician’s likelihood of a positive rating depending on practice location. Broadly speaking, physicians who practiced medicine in the eastern geographic locations of the country had a higher likelihood of being favorably rated than those who practiced in central or western Canada.

Specifically, physicians practicing in New Brunswick (56.3%, P<.001), Newfoundland (56.0%, P<.001), Quebec (53.6%, P<.001), Prince Edward Island (53.6%, P<.001), the Northwest Territories/Yukon/Nunavut (52.7%, P=.13), and Nova Scotia (52.7%, P<.001) were more likely to be rated greater than 4.5, whereas those practicing in Saskatchewan (46.4%, P<.001), Ontario (46.9%, P<.001), British Columbia (46.5%, P<.001), Alberta (46.5%, P<.001), and Manitoba (45.6%, P<.001) were likely to be rated 4.5 or lower (Figure 2; Multimedia Appendix 1).

Figure 2.

Proportion of mean ratings, by province, in the top 50th percentile of all rated physicians (2005-2013) with 95% confidence intervals depicted for each proportion. NB: New Brunswick; NL: Newfoundland and Labrador; QC: Quebec: PE: Prince Edward Island; NT/YT/NU: Northwest Territories/Yukon/Nunavut; NS: Nova Scotia: SK: Saskatchewan; ON: Ontario; BC: British Columbia; AB: Alberta: MB: Manitoba.

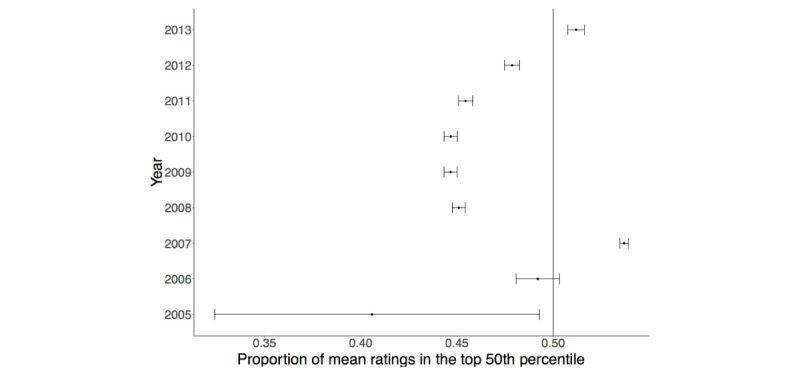

Differences in Online Ratings for Year of Rating

During our study period, there were 640,603 total individual ratings of 27,181 physicians. Over time, the total number of ratings continued to increase; however, we found some important differences in the number of additional new ratings per year (Table 2). In 2005, when the website was still new in Canada, there were only 138 ratings. However, in 2007, 200,650 new ratings were posted before slowly tapering down each subsequent year until 2013, when there were 51,800 new ratings. The year 2007 was also notable in that the mean number of ratings per physician was highest at 5.74 (SD 5.28) before settling at 1 to 3 ratings per physician. In terms of quality of ratings, from 2005 to 2013, physicians were more likely to be rated above the median if rated more recently (ie, in 2013; upper 50th percentile proportion 0.512, P<.001), and the likelihood of favorable ratings increased over time. There were two years (2013 and 2007) when quality of ratings were especially high, whereas for the remaining years the proportion of ratings greater than 4.5 was significantly less than 50% (Figure 3; Multimedia Appendix 1).

Table 2.

Number of ratings, number of physicians, mean ratings per physician, mean overall rating, and additional ratings per year of all physicians rated on RateMDs by province and by year of rating (2005-2013).

| Category | Ratings, n | Physicians, n | Ratings per physician, mean (SD) |

Mean overall rating, mean (SD) |

Additional ratings per year |

|

| Province | ||||||

| New Brunswick | 16,128 | 1447 | 11.15 (8.9) | 4.03 (1.29) | — | |

| Newfoundland | 7564 | 893 | 8.47 (7.2) | 4.09 (1.23) | — | |

| Prince Edward Island | 2534 | 242 | 10.47 (8.0) | 4.00 (1.29) | — | |

| Quebec | 116,041 | 13,460 | 8.62 (8.5) | 4.04 (1.28) | — | |

| Northwest Territories/Yukon/Nunavut | 802 | 126 | 6.37 (6.0) | 3.94 (1.34) | — | |

| Nova Scotia | 23,482 | 1992 | 11.79 (9.5) | 3.99 (1.28) | — | |

| Saskatchewan | 24,093 | 1880 | 12.82 (11.7) | 3.84 (1.34) | — | |

| Ontario | 244,635 | 20,740 | 11.80 (10.4) | 3.86 (1.33) | — | |

| Alberta | 74,077 | 5968 | 12.41 (11.1) | 3.86 (1.32) | — | |

| British Columbia | 101,152 | 8398 | 12.04 (9.9) | 3.87 (1.31) | — | |

| Manitoba | 30,096 | 2266 | 13.28 (12.4) | 3.80 (1.32) | — | |

| Year of rating | ||||||

| 2005 | 138 | 132 | 1.05 (0.2) | 3.75 (1.23) | 138 | |

| 2006 | 7726 | 4280 | 1.77 (1.4) | 3.91 (1.25) | 7588 | |

| 2007 | 208,376 | 34,961 | 5.74 (5.3) | 4.03 (1.23) | 200,650 | |

| 2008 | 293,001 | 28,945 | 2.92 (2.3) | 3.86 (1.32) | 84,625 | |

| 2009 | 375,670 | 28,885 | 2.86 (2.2) | 3.84 (1.33) | 82,669 | |

| 2010 | 454,689 | 30,384 | 2.60 (2.0) | 3.82 (1.35) | 79,019 | |

| 2011 | 525,815 | 30,079 | 2.36 (1.8) | 3.84 (1.33) | 71,126 | |

| 2012 | 588,803 | 29,436 | 2.14 (1.7) | 3.84 (1.37) | 62,988 | |

| 2013 | 640,603 | 27,181 | 1.91 (1.3) | 3.86 (1.42) | 51,800 | |

Figure 3.

Proportion of mean ratings, per year, in the top 50th percentile of all rated physicians (2005-2013) with 95% confidence intervals depicted for each proportion.

Discussion

Using national-level data over a nearly 8-year period from the country’s largest physician-rating website, we found that 57,412 unique physicians are rated online and that, overall, ratings are positive. We found differences in ratings with respect to physician specialty, geographic practice location, and year.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to describe the landscape of physician ratings in Canada. This adds to the body of national-level literature on physician-ratings websites in China, Germany, and the United States [6,10,12-14]. Previous studies have focused on either specific specialties or had shorter study periods [20-26]. Overall, our findings are in keeping with previous work that physician ratings are typically positive [6,12-14,17-19,28].

We found that certain specialties (eg, cardiac surgeons and nephrologists) were more likely to be rated in the top 50th percentile of all rated physicians, whereas others (eg, sleep disorder specialists, dermatologists, and addiction medicine specialists) were less likely to be rated as favorably. A variety of physician and patient factors may contribute to such differences. This may be due to differences in patient population as well as differences in patient expectations. For example, surviving a surgery may be a relatively straightforward “rateable” aspect for a surgeon; insight into recognizing the milestones for recovery from addiction with frequent relapses may not be as straightforward. In addition, there are likely more complex interactions between preconceived expectations patients have regarding their physician, their perceived performance of that physician, and their resulting satisfaction—as well described by the expectation-disconfirmation theory in the psychology and consumer marketing literature [42].

Our results add additional information and detail to previous work. Quality of ratings have been shown to be similar for physicians in primary care, medical specialties, surgeons and surgical specialties, and obstetrics and gynecology, but significantly differed for a category of “other physicians,” which included radiologists, pathologists, and anesthesiologists [6]. Others have shown that pediatricians and surgeons had more favorable ratings, although others showed that ratings for generalists did not differ either in quantity or quality from those for subspecialists [17].

In addition to quality of ratings, we also looked at frequency of ratings by specialty. Certain specialties (eg, obstetrics, dermatology, and family medicine) were more commonly rated than others (ie, pathology and radiology), which based on their proportion in the national physician population, overall, in keeping with previous work [6,12,14]. One hypothesis is that patient-physician encounters during surgeries and pregnancies may be discrete care episodes that may be more amenable to appraisal. Also, specialties such as family medicine involve direct physician-patient interaction over time; in contrast, patients rarely interact with their pathologist or radiologist, the two least-rated specialties. Patients may also more readily attribute care to (and hence, rate) a single provider in the case of a surgeon, obstetrician, or dermatologist, as opposed to settings such as inpatient internal medicine, where multiple physicians may collaborate.

We also found differences in the likelihood of a positive rating for geographic location. It seems unlikely that physician quality vastly differs regionally, given the national accreditation and continuing education standards. We noted, in general, that east coast and territory provinces were more likely to have ratings greater than the median (4.5) compared with provinces west of Ontario. There may be geographic differences in rater expectations for a variety of reasons; for example, location may give rise to differences in accessibility to medical care. One interesting hypothesis is that when physicians are scarce, consumers may be more appreciative of access to a physician and this may bias their ratings in a more favorable manner. In addition, we looked at economic prosperity indicators such as gross domestic product by province and found that, overall, lower patient satisfaction is found in more economically prosperous provinces (ie, central and western provinces) [43], in contrast to a theory by Grigoroudis et al [44] that posits that higher patient satisfaction may be explained by economic prosperity. Moreover, other sociologic or cultural phenomenon across locations may lead to variable consumer preference, a well-described marketing phenomenon known as geographic segmentation [45]. Explanations for such differences are likely multifactorial and remain, as yet, unknown. There is limited research on the variability of online physician ratings with geographic practice location. Gao et al [6] reported that physicians in the southern United States were slightly more likely to be rated favorably than those practicing in the rest of the country. However, others have reported no difference in ratings regarding practice location and city size for certain surgical specialties [20-22].

Finally, we found differences for ratings over time. We suspect that this is due to patient factors, rather than physician factors, because we would not expect physician quality to fluctuate dramatically from year to year, and the survey instrument was consistent throughout the time period. Of note, RateMDs was founded in 2004 in the United States and, by 2005, online physician websites were still new in Canada (138 ratings in 2005). By 2007, popularity peaked at 200,650 ratings before stabilizing and decreasing by 2013. It is challenging to explain this phenomenon. It may be that in 2007, online physician ratings finally received public attention, resulting in a flood of “early adopters,” which subsequently waned. There was sufficient popularity of such websites and several prominent nationwide media articles in 2007 that physicians became concerned about their use. One article in a popular national news source reported the Canadian Medical Association’s displeasure at such sites and, in particular, warned of the potential for libel [46-48]. However, our findings suggest that these early users were actually more likely to post favorable ratings. This may be plausible, if only because physician-rating website users in general tend to have more positive views toward the Internet, despite no differences in total quantity of Internet usage from the general population [16]. This is in keeping with our finding that the likelihood of a positive rating was highest in 2007.

Since 2007, ratings stabilized and even decreased in absolute number through to 2013. This finding differs from US data, which shows physician-rating website usage rapidly increasing, although the study period in question spans a 5-year period that ends before this study making comparisons problematic [6]. Based on user traffic to competing physician websites in Canada, it does not appear that increasing popularity of competing websites is the explanation. Compared to the United States, in Canada there is comparatively less consumer choice in physician selection because the avenue to seek subspecialty consultation is via one’s primary care physician rather than self-referral. This may, in turn, be driving a decrease in the popularity of physician-rating websites. This hypothesis has been used to explain the use of physician websites in England; although increasing over time as well, they have demonstrated a more gradual, stable rise in popularity compared to the rapidly accelerating US growth [39].

We acknowledge several limitations to our work. First, although our dataset spans nearly an 8-year period, we are missing data from a period of 3 months (ie, October-December 2013 to complete calendar year 2013). However, we feel a national database of greater than 57,000 physicians for nearly an 8-year period is sufficient to elucidate broad trends. Second, online physician-ratings data may not be generalizable. Rating website users likely differ from the general population by virtue of computer access and ability, and by their inclination to post ratings [30]. In addition, because all physicians are entered into the website by raters, it is possible that a physician may have two unique profiles. This database was deidentified; therefore, we were unable to ensure that duplicate profiles were corrected. Moreover, ratings are anonymously posted, so it is possible that fraudulent ratings exist; however, the website has quality control mechanisms in place to circumvent multiple fraudulent ratings (eg, deleting multiple reviews from a single Web address). Third, we could not control for the possibility that online ratings may, themselves, influence future ratings. For example, when a user logs onto the website to post a rating, their original inclination may be influenced by what has previously been published. Overall, these are issues that are germane to most physician-ratings websites and, on balance, we do not feel these limitations would significantly alter our observations, greatly affect broad trends of average ratings and regional differences, nor affect our conclusions.

This study provides new national-level information on the nature of online physician ratings, particularly regarding specialty, geographic practice location, and changes over time. It remains to be seen whether such trends will continue. The utility of online ratings for ascertaining and evaluating physician quality is still in question—and we would argue that before undertaking these larger questions, a better understanding of the scope and breadth of online physician ratings is required. Our study has shown important differences in how physicians are rated based on a physician’s specialty, practice location, and the year in which the physician is rated. Further studies endeavor to better understand the scope, breadth, and utility of online physician ratings; in the meantime, what we do know is that such websites reflect the unsolicited views of the health care consumer and, as such, remain a valuable data source of the patient experience.

Abbreviations

- CIHI

Canadian Institute of Health Information

Proportion of ratings in top 50th percentile.

Footnotes

Authors' Contributions: All authors (JL, JM, CB) had access to the data and contributed to the conception or design of the work; the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data; the writing of the manuscript; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Stelfox HT, Gandhi TK, Orav EJ, Gustafson Ml. The relation of patient satisfaction with complaints against physicians and malpractice lawsuits. Am J Med. 2005;118:1126–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hickson GB, Federspiel CF, Pichert JW, Miller CS, Gauld-Jaeger J, Bost B. Patient complaints and malpractice risk. JAMA. 2002;287:2951–2957. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.22.2951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boulding W, Glickman SW, Manary MP, Schulman KA, Staelin R. Relationship between patient satisfaction with inpatient care and hospital readmission within 30 days. Am J Manag Care. 2011 Jan;17(1):41–48. http://www.ajmc.com/pubMed.php?pii=12805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glickman SW, Boulding W, Manary M, Staelin R, Roe MT, Wolosin RJ, Ohman EM, Peterson ED, Schulman KA. Patient satisfaction and its relationship with clinical quality and inpatient mortality in acute myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010 Mar;3(2):188–195. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.900597. http://circoutcomes.ahajournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=20179265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sacks GD, Lawson EH, Dawes AJ, Russell MM, Maggard-Gibbons M, Zingmond DS, Ko CY. Relationship between hospital performance on a patient satisfaction survey and surgical quality. JAMA Surg. 2015 Sep;150(9):858–864. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2015.1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao GG, McCullough JS, Agarwal R, Jha AK. A changing landscape of physician quality reporting: analysis of patients' online ratings of their physicians over a 5-year period. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(1):e38. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2003. http://www.jmir.org/2012/1/e38/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McLennan S, Strech D, Reimann S. Developments in the frequency of ratings and evaluation tendencies: a review of German physician rating websites. J Med Internet Res. 2017 Aug 25;19(8):e299. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6599. http://www.jmir.org/2017/8/e299/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.NHS Choices. [2017-10-23]. Find hospital-consultants https://www.nhs.uk/Service-Search/Hospital/LocationSearch/8/Consultants .

- 9.Weisse Liste. [2017-10-23]. https://www.weisse-liste.de/de/arzt/arztsuche/

- 10.Hanauer DA, Zheng K, Singer DC, Gebremariam A, Davis MM. Public awareness, perception, and use of online physician rating sites. JAMA. 2014 Feb 19;311(7):734–735. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.283194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Emmert M, Sauter L, Jablonski L, Sander U, Taheri-Zadeh F. Do physicians respond to web-based patient ratings? An analysis of physicians' responses to more than one million web-based ratings over a six-year period. J Med Internet Res. 2017 Jul 26;19(7):e275. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7538. http://www.jmir.org/2017/7/e275/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Emmert M, Meier F. An analysis of online evaluations on a physician rating website: evidence from a German public reporting instrument. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(8):e157. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2655. http://www.jmir.org/2013/8/e157/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Emmert M, Sander U, Pisch F. Eight questions about physician-rating websites: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(2):e24. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2360. http://www.jmir.org/2013/2/e24/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hao H. The development of online doctor reviews in China: an analysis of the largest online doctor review website in China. J Med Internet Res. 2015 Jun 01;17(6):e134. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4365. http://www.jmir.org/2015/6/e134/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merrell JG, Levy BH, Johnson DA. Patient assessments and online ratings of quality care: a “wake-up call” for providers. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013 Nov;108(11):1676–1685. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Terlutter R, Bidmon S, Röttl J. Who uses physician-rating websites? Differences in sociodemographic variables, psychographic variables, and health status of users and nonusers of physician-rating websites. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(3):e97. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3145. http://www.jmir.org/2014/3/e97/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lagu T, Hannon NS, Rothberg MB, Lindenauer PK. Patients' evaluations of health care providers in the era of social networking: an analysis of physician-rating websites. J Gen Intern Med. 2010 Sep;25(9):942–946. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1383-0. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/20464523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kadry B, Chu LF, Kadry B, Gammas D, Macario A. Analysis of 4999 online physician ratings indicates that most patients give physicians a favorable rating. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(4):e95. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1960. http://www.jmir.org/2011/4/e95/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Emmert M, Meier F, Heider A, Dürr C, Sander U. What do patients say about their physicians? An analysis of 3000 narrative comments posted on a German physician rating website. Health Policy. 2014 Oct;118(1):66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frost C, Mesfin A. Online reviews of orthopedic surgeons: an emerging trend. Orthopedics. 2015 Apr;38(4):e257–e262. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20150402-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ellimoottil C, Hart A, Greco K, Quek ML, Farooq A. Online reviews of 500 urologists. J Urol. 2013 Jun;189(6):2269–2273. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nwachukwu BU, Adjei J, Trehan SK, Chang B, Amoo-Achampong K, Nguyen JT, Taylor SA, McCormick F, Ranawat AS. Rating a sports medicine surgeon's “quality” in the modern era: an analysis of popular physician online rating websites. HSS J. 2016 Oct;12(3):272–277. doi: 10.1007/s11420-016-9520-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sobin L, Goyal P. Trends of online ratings of otolaryngologists: what do your patients really think of you? JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014 Jul;140(7):635–638. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2014.818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gilbert K, Hawkins CM, Hughes DR, Patel K, Gogia N, Sekhar A, Duszak R. Physician rating websites: do radiologists have an online presence? J Am Coll Radiol. 2015 Aug;12(8):867–871. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2015.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riemer C, Doctor M, Dellavalle RP. Analysis of online ratings of dermatologists. JAMA Dermatol. 2016 Feb;152(2):218–219. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.4991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trehan SK, Daluiski A. Online patient ratings: why they matter and what they mean. J Hand Surg Am. 2016 Feb;41(2):316–319. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2015.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanauer DA, Zheng K, Singer DC, Gebremariam A, Davis MM. Parental awareness and use of online physician rating sites. Pediatrics. 2014 Oct;134(4):e966–e975. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0681. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=25246629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.López A, Detz A, Ratanawongsa N, Sarkar U. What patients say about their doctors online: a qualitative content analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2012 Jun;27(6):685–692. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1958-4. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/22215270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holliday AM, Kachalia A, Meyer GS, Sequist TD. Physician and patient views on public physician rating websites: a cross-sectional study. J Gen Intern Med. 2017 Jun;32(6):626–631. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-3982-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Segal J, Sacopulos M, Sheets V, Thurston I, Brooks K, Puccia R. Online doctor reviews: do they track surgeon volume, a proxy for quality of care? J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(2):e50. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2005. http://www.jmir.org/2012/2/e50/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gray BM, Vandergrift JL, Gao GG, McCullough JS, Lipner RS. Website ratings of physicians and their quality of care. JAMA Intern Med. 2015 Feb;175(2):291–293. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.6291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adelhardt T, Emmert M, Sander U, Wambach V, Lindenthal J. Can patients rely on results of physician rating websites when selecting a physician? - A cross-sectional study assessing the association between online ratings and structural and quality of care measures from two German physician rating websites. Value Health. 2015 Nov;18(7):A545. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2015.09.1732. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1098-3015(15)03808-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu JJ, Matelski J, Cram P, Urbach DR, Bell CM. Association between online physician ratings and cardiac surgery mortality. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes Nov. 2016;9(6):788–791. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.116.003016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Okike K, Peter-Bibb TK, Xie KC, Okike ON. Association between physician online ratings and quality of care. J Med Internet Res. 2016 Dec 13;18(12):e324. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6612. http://www.jmir.org/2016/12/e324/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Verhoef LM, Van de Belt TH, Engelen LJ, Schoonhoven L, Kool RB. Social media and rating sites as tools to understanding quality of care: a scoping review. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(2):e56. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3024. http://www.jmir.org/2014/2/e56/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murphy GP, Awad MA, Osterberg EC, Gaither TW, Chumnarnsongkhroh T, Washington SL, Breyer BN. Web-based physician ratings for California physicians on probation. J Med Internet Res. 2017 Aug 22;19(8):e254. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7488. http://www.jmir.org/2017/8/e254/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Daskivich TJ, Houman J, Fuller G, Black JT, Kim HL, Spiegel B. Online physician ratings fail to predict actual performance on measures of quality, value, and peer review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2017 Sep 08;:e1. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocx083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Emmert M, Adelhardt T, Sander U, Wambach V, Lindenthal J. A cross-sectional study assessing the association between online ratings and structural and quality of care measures: results from two German physician rating websites. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):414. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-1051-5. http://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-015-1051-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Greaves F, Millett C. Consistently increasing numbers of online ratings of healthcare in England. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(3):e94. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2157. http://www.jmir.org/2012/3/e94/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.RateMDs. [2017-02-08]. https://www.ratemds.com/

- 41.Canadian Institute for Health Information. [2017-02-08]. https://secure.cihi.ca/estore/productSeries.htm?pc=PCC476 .

- 42.Oliver RL. Effect of expectation and disconfirmation on postexposure product evaluations-an alternative interpretation? J Applied Psych. 1977;62(4):480. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Statistics Canada. [2017-11-06]. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/tables-tableaux/sum-som/l01/cst01/econ15-eng.htm .

- 44.Grigoroudis E, Nikolopoulou G, Zopounidis C. Customer satisfaction barometers and economic development: an explorative ordinal regression analysis. Total Qual Manag Bus. 2008 May;19(5):441–460. doi: 10.1080/14783360802018095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kahle LR. The nine nations of North America and the value basis of geographic segmentation. J Marketing. 1986 Apr;50(2):37–47. doi: 10.2307/1251598. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mackay B. RateMDs.com nets ire of Canadian physicians. CMAJ. 2007 Mar 13;176(6):754. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.070239. http://www.cmaj.ca/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=17353522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.CBC News Technology and Science. 2007. Mar 12, [2017-02-08]. Doctor rating website stirs up physicians http://www.cbc.ca/news/technology/doctor-rating-website-stirs-up-physicians-1.683440 .

- 48.Smart Canucks. [2017-02-08]. RateMDs.com allows patients to rate and read about their doctors and dentists [thread] http://forum.smartcanucks.ca/18448-ratemds-com-allows-patients-rate-read-about-their-doctors-dentists-canada/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Proportion of ratings in top 50th percentile.