Abstract

Background

To evaluate the neointimal conditions of everolimus-eluting stents (EESs) implanted in culprit lesions of patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) compared with stable angina pectoris (SAP) using optical coherence tomography (OCT). EESs are second-generation drug-eluting stents that have recently been shown to be useful in patients with ACS as well as in patients with SAP. However, few studies have analyzed the intra-stent conditions of EESs that can lead to favorable results in such ACS lesions.

Methods

We evaluated 41 ACS patients with EES implantation (age, 66.7 ± 10.3 years) and 59 SAP patients enrolled as controls (age, 68.3 ± 10.7 years). OCT examinations were performed after 9 months of follow-up after stent implantation, and the condition of the neointimal coverage over every stent strut was assessed in 1-mm intervals. In addition, neointimal thickness (NIT) over each strut was measured and tissue characteristics were examined.

Results

There was no significant difference in mean NIT between the ACS (90.8 ± 88.2 mm) and SAP (87.3 ± 74.2 mm, p = 0.11) group. The rate of uncovered struts was significantly lower in the ACS group (11.5%) than in the SAP group (12.5%, p = 0.03). Neointimal tissue characteristics were also similar between groups.

Conclusions

Vascular responses after EES implantation differed significantly between ACS and SAP lesions using OCT. However, these differences were considered small in clinical terms. Our OCT data support the favorable results of patients with EES implantation at mid-term follow-up, even in those with ACS.

Keywords: Acute coronary syndrome, Drug-eluting stent, Everolimus-eluting stent, Optical coherence tomography, Percutaneous coronary intervention

INTRODUCTION

Stent implantation has been used to treat coronary artery stenosis for several decades. Treatment with bare metal stents (BMSs) can successfully restore the acute vessel lumen, but long-term outcomes are often compromised by in-stent restenosis (ISR). The first generation of drug-eluting stents (DESs) markedly reduced ISR compared with BMSs, however patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) have been shown to have a greater risk of thrombotic complications after first-generation DES implantation compared to those with stable angina pectoris (SAP).1,2 A recent clinical trial suggested the superiority of everolimus-eluting stents (EESs), a so-called second-generation DES, over BMSs even in patients with ACS.3 Treating ACS with second-generation DESs is now the established and preferred therapeutic option. Although recent clinical trials have reported that implanted EESs show improved efficacy and safety compared with BMSs, few studies have analyzed the intra-stent conditions of EESs that could lead to favorable results in such ACS lesions. Therefore, the aim of this study was to compare vascular responses in lesions treated with EES implantation using optical coherence tomography (OCT), which is the gold standard for assessing intra-stent conditions between ACS and SAP lesions.

METHODS

Study population

Consecutive patients who underwent percutaneous coronary interventions (PCIs) with EESs (XienceTM; Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, CA) for de novo lesions at Nara Medical University Hospital from October 2010 to February 2014 were enrolled. Patients with ACS and SAP were retrospectively analyzed and compared in this study. The interventional strategy and stent selection were left to the discretion of the operator. All patients received 100 mg of aspirin with either 75 mg of clopidogrel or 200 mg of ticlopidine after the PCI.

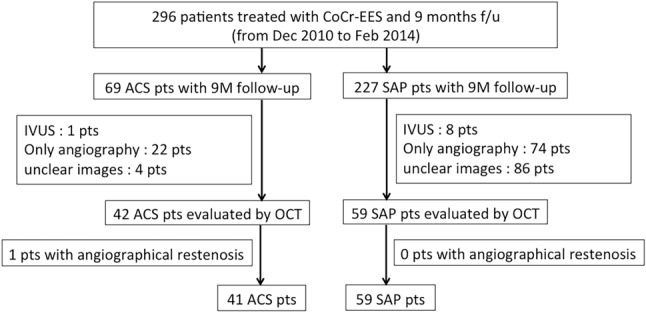

Follow-up (9 months) coronary angiography is routinely performed in our institution. Dual antiplatelet therapy was generally continued until follow-up coronary angiography. All of the enrolled patients received OCT examinations (ILUMIEN or ILUMIEN OPTIS OCT Intravascular Imaging System; St. Jude Medical, St. Paul, MN) during follow-up coronary angiography. We excluded patients with ISR or unclear OCT images due to insufficient blood removal at the 9-month follow-up coronary angiography (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Patient flow chart. ACS, acute coronary syndrome; CoCr, cobalt chrome; f/u, follow-up; IVUS, intravascular ultrasound; M, months; OCT, optical coherence tomography; pts, patients; SAP, stable angina pectoris; TLR, target lesion revascularization.

This study was complied with the Declaration of Helsinki with regard to investigations in humans. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Nara Medical University, and written informed consent was obtained from each patient prior to enrolment.

OCT imaging and analysis

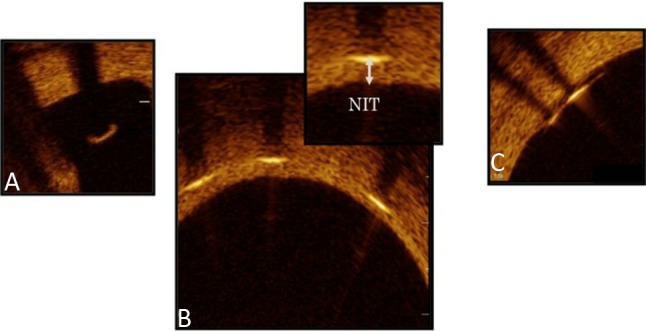

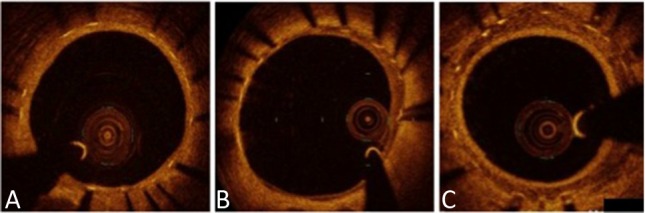

OCT was performed during follow-up angiography after the administration of intracoronary nitroglycerin (0.2 mg). An OCT catheter was placed distal (> 10 mm) to the stented lesion and pulled back using an automatic pull back system. Cross-sectional OCT images of the stented segments at 1-mm intervals were analyzed. We evaluated the apposition and neointimal coverage of each stent strut and neointimal characteristics. Incomplete stent apposition was defined as a strut detached by more than 108 μm from the inner vessel wall. This definition was made based on the resolution limit of OCT (20 μm) and both strut thickness (81 μm) and polymer thickness of the EES (7 μm).4,5 A covered strut was defined as a neointimal thickness (NIT), defined as the distance between the center of the strut and the neointimal surface, of > 30 μm (Figure 2).6 We classified the neointimal tissue characteristics into three patterns: homogeneous, heterogeneous, and layered (Figure 3).7 Thrombus was defined as a mass protruding into the lumen with an irregular surface.8 The OCT findings were then compared between the ACS and SAP groups.

Figure 2.

Stent strut condition by optical coherence tomography images. (A) Malapposed strut without coverage. (B) Covered struts and neointimal thickness (NIT). (C) Well-apposed struts to the vessel wall without coverage.

Figure 3.

Neointimal tissue characteristics on optical coherence tomography. (A) Homogeneous pattern. (B) Heterogeneous pattern. (C) Layered pattern.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation or median (25th, 75th percentiles), and were compared using the Student’s t-test. Categorical variables are expressed as percentages and were compared using the chi-square test. A p value of < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using JMP for Mac version 11.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

A total of 100 patients (100 lesions) including 41 with ACS [acute myocardial infarction (AMI), n = 34; unstable angina pectoris, n = 7] and 59 with SAP were studied. The baseline clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. In terms of risk factors, past smokers were more frequent in the ACS group than in the SAP group. The baseline medications are shown in Table 2. Calcium channel blockers were preferentially used for hypertension in the SAP group, and the ACS group more frequently received β-blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-Is) than the SAP group. At the 9-month follow-up visit, dual antiplatelet therapy was interrupted for non-cardiac surgery in one patient with ACS (2.50%) and four with SAP (6.06%, p = 0.35). The procedural characteristics are listed in Table 3. The target vessel, selected stent size and balloon diameter used for post-dilatation were similar between groups.

Table 1. Baseline clinical characteristics.

| ACS | SAP | p value | |

| No. of patients | 41 (AMI 34 UAP 7) | 59 | |

| Male gender, n (%) | M 34 (82.9), F 7 | M 45 (76.3), F 14 | 0.42 |

| Age, years old | 66.7 ± 10.3 | 68.3 ± 10.7 | 0.43 |

| Follow up, days | 304 ± 68.7 | 284 ± 63.2 | 0.07 |

| Risk factor | |||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 27 (65.9) | 45 (76.3) | 0.25 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 38 (92.7) | 51 (86.4) | 0.33 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 16 (39.0) | 20 (33.9) | 0.60 |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 3 (7.32) | 6 (10.2) | 0.62 |

| Past smoker, n (%) | 29 (70.7) | 27 (45.8) | 0.01 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.5 ± 3.82 | 24.3 ± 4.00 | 0.22 |

| Family history, n (%) | 14 (34.2) | 17 (28.8) | 0.57 |

| Previous cardiac surgery | 0 | 0 | 1.00 |

| Hemodyalysis, n (%) | 3 (7.50) | 5 (8.47) | 0.86 |

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; BMI, body mass index; ISR, in-stent restenosis; SAP, stable angina pectoris.

Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or n (%).

Table 2. Baseline medications.

| ACS | SAP | p value | |

| Aspirin, n (%) | 41 (100) | 56 (94.9) | 0.14 |

| Clopidogrel, n (%) | 40 (97.6) | 57 (96.6) | 0.78 |

| Ticlopidine, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.69) | 0.40 |

| Warfarin, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.00 |

| Cilostazol, n (%) | 1 (2.44) | 4 (6.78) | 0.33 |

| EPA, n (%) | 2 (4.88) | 2 (3.39) | 0.71 |

| Statin, n (%) | 38 (92.7) | 51 (86.4) | 0.33 |

| Nicorandil, n (%) | 7 (17.1) | 8 (13.6) | 0.63 |

| Isosorbide, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.69) | 0.40 |

| Nytroglycerin, n (%) | 1 (2.44) | 3 (5.08) | 0.51 |

| CCB, n (%) | 8 (19.5) | 26 (44.1) | 0.01 |

| β blocker, n (%) | 27 (65.9) | 21 (35.6) | < 0.01 |

| ACE-I, n (%) | 25 (61.0) | 13 (22.0) | < 0.01 |

| ARB, n (%) | 16 (39.2) | 27 (45.8) | 0.50 |

| Insulin, n (%) | 2 (4.88) | 5 (8.47) | 0.49 |

ACE-I, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; ACS, acute coronary syndrome; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; CCB, calcium channel blocker; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; SAP, stable angina pectoris.

Values are numbers (%) of patients.

Table 3. Procedural characteristics.

| ACS | SAP | p value | |

| No. of target lesion, n (%) | 0.15 | ||

| LAD | 28 (68.3) | 34 (57.6) | |

| LCX | 1 (2.44) | 8 (13.6) | |

| RCA | 12 (29.3) | 17 (28.8) | |

| No. of stent, n | 46 | 67 | |

| Stent diameter, mm | 2.85 ± 0.33 | 2.87 ± 0.41 | 0.96 |

| Stent length, mm | 22.9 ± 7.25 | 23.9 ± 8.83 | 0.77 |

| Post dilatation, n (%) | 38 (92.7) | 53 (89.8) | 0.62 |

| Balloon diameter for post dilatation, mm | 2.98 ± 0.33 | 3.10 ± 0.50 | 0.23 |

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; LAD, left anterior descending artery; LCX, left circumflex artery; RCA, right coronary artery; SAP, stable angina pectoris.

Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or n (%).

OCT examinations at follow-up

A total of 2540 OCT cross-sections and 20622 stent struts were analyzed. The OCT findings are shown in Table 4. The minimum lumen area and mean NIT at 9 months of follow-up were similar between the ACS and SAP groups. Most stent struts were well-apposed to the vessel wall in both groups. However, uncovered stent struts were observed significantly less frequently in the ACS group than in the SAP group. No evidence of thrombus was detected in either group. With regards to neointimal tissue characteristics, no significant differences were noted between the groups, with a homogeneous pattern in more than 98% in each.

Table 4. OCT findings at follow-up angiography.

| ACS | SAP | p value | |

| Cross-sections, n | 1000 | 1540 | |

| Total struts, n | 8023 | 12599 | |

| MLA in stented segment, mm2 | 5.66 ± 1.63 | 5.50 ± 2.06 | 0.36 |

| Neointimal area at MLA site, mm2 | 1.30 ± 1.14 | 1.07 ± 0.81 | 0.47 |

| Median NIT, μm | 70 (IQR; 40-120) | 60 (IQR; 40-120) | 0.11 |

| Average NIT, μm | 90.8 ± 88.2 | 87.3 ± 74.2 | 0.11 |

| Presence of thrombi, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 1.00 |

| Uncovered struts, n (%) | 922 (11.5) | 1574 (12.5) | 0.03 |

| Well-apposed struts, n (%) | 7981 (99.5) | 12541 (99.5) | 0.52 |

| Neointimal characteristics | |||

| Homogeneous pattern, n (%) | 983 (98.3) | 1525 (99.0) | 0.11 |

| Heterogeneous pattern, n (%) | 4 (0.40) | 4 (0.26) | 0.54 |

| Layered pattern, n (%) | 13 (1.3) | 11 (0.71) | 0.14 |

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; MLA, minimum lumen area; NIT, neointimal thickness; SAP,stable angina pectoris.

Neointimal area defined as stent area – lumen area.

Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or n (%).

DISCUSSION

The main findings of this study areas follows: 1) the mean NIT of EESs implanted in the culprit lesions of the ACS group were not significantly different compared with the SAP group; 2) the rate of uncovered struts was significantly lower in the ACS group than in the SAP group at 9 months of follow-up; and 3) the neointimal tissue characteristics were similar between the groups. These results are similar to previous studies of vessel reactions to EESs.4,9,10 The mean NIT and apposition of the stent struts in these previous studies ranged from 100 to 119 μm for NIT and 97.3% to 99.9% for apposition of stent struts.

With first-generation sirolimus-eluting stents, previous OCT studies have shown that the incidence of incomplete stent apposition and inadequate coverage were significantly greater in ACS lesions than in SAP lesions at mid-term follow-up, and that this deficient stent condition remained at long-term follow-up.11,12 In ACS patients, culprit lesions often showed plaque rupture and a proportion of ruptured cavities persisted even at follow-up. Stent struts implanted at such ruptured sites demonstrated persistent or late acquired incomplete stent apposition at follow-up. These findings represent risk factors for late or very late stent thrombosis13,14 and could explain why first-generation DES implantation is more frequently associated with clinical events during follow-up in ACS patients than in SAP patients. In contrast to first-generation DESs, a previous OCT study and the present results showed that second-generation EES implants promoted a favorable arterial healing response in terms of stent strut apposition and coverage, even in patients with ACS.9 These OCT data may support better clinical outcomes of EESs in ACS patients than in SAP patients.

The frequency of uncovered struts was significantly lower in the ACS lesions than in the SAP lesions in the present study. The culprit lesions in the patients with ACS showed local but stronger inflammation within vulnerable plaques compared to those in the patients with SAP.15 In a previous intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) study in the BMS era, systemic inflammation conditions such as diabetes mellitus were reported to possibly increase neointimal hyperplasia.16 We therefore speculate that the enhanced inflammation in ACS lesions may have stimulated neointimal proliferation, leading to a low rate of uncovered struts after EES implantation compared with SAP lesions. In the DES era, late or very late stent thrombosis is a rare but fatal event. Some studies have reported that incomplete stent strut coverage is a morphologic risk factor for stent thrombosis.17-19 The lower rate of uncovered struts in the ACS patients with EES implantation in the present study implies that the use of EESs for patients with ACS may prevent stent thrombosis.

With regards to qualitative OCT analysis, we analyzed the neointimal characteristics using OCT, and more than 98% of the cases with neointimal hyperplasia showed a homogeneous pattern comprising smooth muscle cells with rich collagen and elastin, even in the patients with ACS.20 Furthermore, no evidence of thrombus detected by OCT was seen in our study. Considering previous OCT results and our favorable results, EESs with low-dose everolimus (100 μg/cm2) and a fluoropolymer with antithrombotic effects may provide an excellent vascular healing profile, even when the EES is implanted in ACS culprit lesions.21 Fukuhara et al. reported that neointimal characteristics detected by OCT after DES implantation maybe related to late neointimal progression or regression, and that neointima with a homogeneous pattern was the only predictor of late neointimal regression during mid-term follow-up.20 The relationship between neointimal characteristics and long-term neointimal behavior including atherosclerotic changes within neointima (neoatherosclerosis) remains unclear. Patients treated with EESs should thus receive long-term follow-up, irrespective of whether they have ACS or SAP.

Several limitations must be considered when interpreting the present study. First, this study was a single-center, retrospective, observational study. There was no randomization. In addition, the sample size was relatively limited, raising the possibility of selection bias. These limitations mean that we cannot make definitive conclusions. Second, we analyzed the strut condition without considering within-lesion correlation matrix, which may have led to lesion bias. Third, we did not evaluate patients with ISR and other types of stents. Finally, the follow-up period was limited to 9 months. Therefore we could not assess the correlations between the OCT findings and clinical outcomes such as stent thrombosis and late catch-up ISR. Studies with long-term follow-up and a larger population are needed to confirm our results.

CONCLUSIONS

Vascular response after EES implantation differed significantly between ACS and SAP lesions using OCT. However, these differences were considered small in terms of clinical relevance. Our OCT data support the favorable results of patients with EES implantation at mid-term follow-up, even in ACS patients. However, careful long-term follow-up is warranted.

DECLARATION OF CONFLICT OF INTEREST

All the authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Morice MC, Serruys PW, Sousa JE, et al. A randomized comparison of a sirolimus-eluting stent with a standard stent for coronary revascularization. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1773–1780. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Urban P, Gershlick AH, Guagliumi G, et al. Safety of coronary sirolimus-eluting stents in daily clinical practice:one-year follow-up of the e-Cypher registry. Circulation. 2006;113:1434–1441. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.532242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palmerini T, Biondi-Zoccai G, Della Riva D, et al. Clinical outcomes with drug-eluting and bare-metal stents in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: evidence from a comprehensive network meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:496–504. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inoue T, Shite J, Yoon J, et al. Optical coherence evaluation of everolimus-eluting stents 8 months after implantation. Heart. 2011;97:1379–1384. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2010.204339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanigawa J, Barlis P, Di Mario C. Intravascular optical coherence tomography: optimisation of image acquisition and quantitative assessment of stent strut apposition. EuroIntervention. 2007;3:128–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sawada T, Shite J, Negi N, et al. Factors that influence measurements and accurate evaluation of stent apposition by optical coherence tomography. Assessment using a phantom model. Circ J. 2009;73:1841–1847. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-09-0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonzalo N, Serruys PW, Okamura T, et al. Optical coherence tomography patterns of stent restenosis. Am Heart J. 2009;158:284–293. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kume T, Akasaka T, Kawamoto T, et al. Assessment of coronary arterial thrombus by optical coherence tomography. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97:1713–1717. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mizoguchi T, Sawada T, Shinke T, et al. Detailed comparison of intra-stent conditions 12 months after implantation of everolimus-eluting stents in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction or stable angina pectoris. Int J Cardiol. 2014;171:224–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi HH, Kim JS, Yoon DH, et al. Favorable neointimal coverage in everolimus-eluting stent at 9 months after stent implantation: comparison with sirolimus-eluting stent using optical coherence tomography. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;28:491–497. doi: 10.1007/s10554-011-9849-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hassan AK, Bergheanu SC, Stijnen T, et al. Late stent malapposition risk is higher after drug-eluting stent compared with bare-metal stent implantation and associates with late stent thrombosis. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:1172–1180. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kubo T, Imanishi T, Kitabata H, et al. Comparison of vascular response after sirolimus-eluting stent implantation between patients with unstable and stable angina pectoris a serial optical coherence tomography study. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging. 2008;1:475–484. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cook S, Wenaweser P, Togni M, et al. Incomplete stent apposition and very late stent thrombosis after drug-eluting stent implantation. Circulation. 2007;115:2426–2434. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.658237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishigami K, Uemura S, Morikawa Y, et al. Long-term follow-up of neointimal coverage of sirolimus-eluting stents--evaluation with optical coherence tomography. Circ J. 2009;73:2300–2307. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-08-1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hansson GK, Libby P, Tabas I. Inflammation and plaque vulnerability. J Intern Med. 2015;278:483–493. doi: 10.1111/joim.12406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kornowski R, Mintz GS, Kent KM, et al. Increased restenosis in diabetes mellitus after coronary interventions is due to exaggerated intimal hyperplasia. A serial intravascular ultrasound study. Circulation. 1997;95:1366–1369. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.6.1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jimenez-Valero S, Moreno R, Sanchez-Recalde A. Very late drug-eluting stent thrombosis related to incomplete stent endothelialization: in-vivo demonstration by optical coherence tomography. J Invasive Cardiol. 2009;21:488–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wenaweser P, Daemen J, Zwahlen M, et al. Incidence and correlates of drug-eluting stent thrombosis in routine clinical practice. 4-year results from a large 2-institutional cohort study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1134–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Finn AV, Joner M, Nakazawa G, et al. Pathological correlates of late drug-eluting stent thrombosis strut coverage as a marker of endothelialization. Circulation. 2007;115:2435–2441. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.693739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fukuhara K, Okura H, Kume T, et al. In-stent neointimal characteristics and late neointimal response after drug-eluting stent implantation: a preliminary observation. J Cardiol. 2016;67:437–441. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2015.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kolandaivelu K, Swaminathan R, Gibson WJ, et al. Stent thrombogenicity early in high-risk interventional settings is driven by stent design and deployment and protected by polymer-drug coatings. Circulation. 2011;123:1400–1409. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.003210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]