Abstract

Rhabdomyoma, by definition is a benign muscle tumour.. Rhabdomyomas constitute 2% of all myogenous neoplasms. This tumour is in incongruence with other benign soft tissue tumours, in that it is rarer than its malignant counterpart. They are broadly categorised as cardiac and extra-cardiac. Three different subtypes exists as 1) the adult type, 2) the fetal type and 3) the genital type, the adult type being the most common.[1] AR (Adult Rhabdomyoma) generally occurs in the 4th and 5th decade with a male predilection.[2] There have been very few presentations of this lesion in the paediatric age group. Here we present a case of lingual adult rhabdomyoma in an 11 year old girl.

Keywords: Adult rhabdomyoma, muscle tumor, tongue

Introduction

Rhabdomyoma, by definition, is a benign muscle tumor. Rhabdomyomas constitute 2% of all myogenous neoplasms. This tumor is in incongruence with other benign soft tissue tumors, in that it is rarer than its malignant counterpart. They are broadly categorized as cardiac and extracardiac. Three different subtypes exist as: (1) the adult type, (2) the fetal type, and (3) the genital type, the adult type being the most common.[1] Adult rhabdomyoma (AR) generally occurs in the 4th and 5th decades with a male predilection.[2] There have been very few presentations of this lesion in the pediatric age group. Here, we present a case of lingual AR in an 11-year-old girl.

Solitary tongue lesions are a diagnostic challenge as they have a wide range of differential diagnosis. The diagnosis of rhabdomyoma is further difficult as it is mainly dependant on its characteristic histopathological and immunohistochemistry findings. The purpose of this article is to present our findings of the case with an appraisal of literature on the incidence of such cases in children.

Case Report

An 11-year-old female patient reported with a painless swelling over the right lateral border of the tongue for the past 4 months. There was no history of trauma in that region. There was complaint of slight dysphagia and globus sensation. Medical history and general physical examination were unremarkable. There was no regional lymphadenopathy.

On physical examination, there was a single 2 cm × 2 cm soft, well-delineated, nontender mass occupying the right lateral aspect of the tongue.

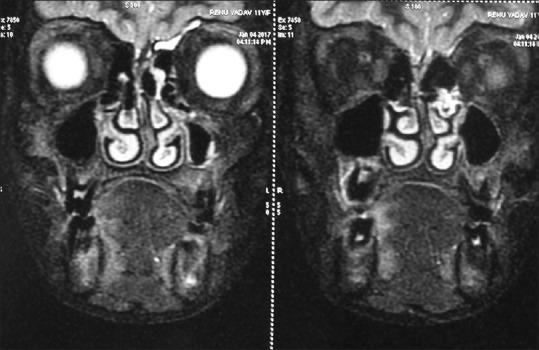

The swelling was sessile, submucosal, and firm in consistency with a smooth surface. Overlying mucosa was normal in appearance and not fixed. Tongue movements and speech were normal. The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a medium-sized hyperintense lesion arising from the anterior two-third of the right half of the tongue along the lateral border on T2-weighted images measuring 1.9 cm × 1.3 cm × 1.9 cm [Figure 1]. Heterogenous enhancement of the lesion on intravenous administration of Gd-DTPA was observed. The MRI was suggestive of involvement of the intrinsic muscles of the tongue on the right side with no involvement of the lingual neurovascular bundle or the base of the tongue. Level IB and II lymph nodes were enlarged bilaterally.

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging T2-weighed image showing hyperintense lesion

An incisional biopsy was done for the patient under local anesthesia and was submitted for histopathological examination. The lesion was suggestive of AR. The mass was explored under general anesthesia with an intraoral approach. The tumor mass was marked with methylene blue. An elliptical incision was marked around the tumor mass and it was excised from the surrounding musculature of the tongue [Figure 2]. Care was taken to preserve all the adjacent vital structures; a two-layer primary closure was done with 3-0 vicryl. No postoperative complications were noted. There was no recurrence noted up to 2 years of follow-up.

Figure 2.

Intraoperative photograph showing excision of the lesion

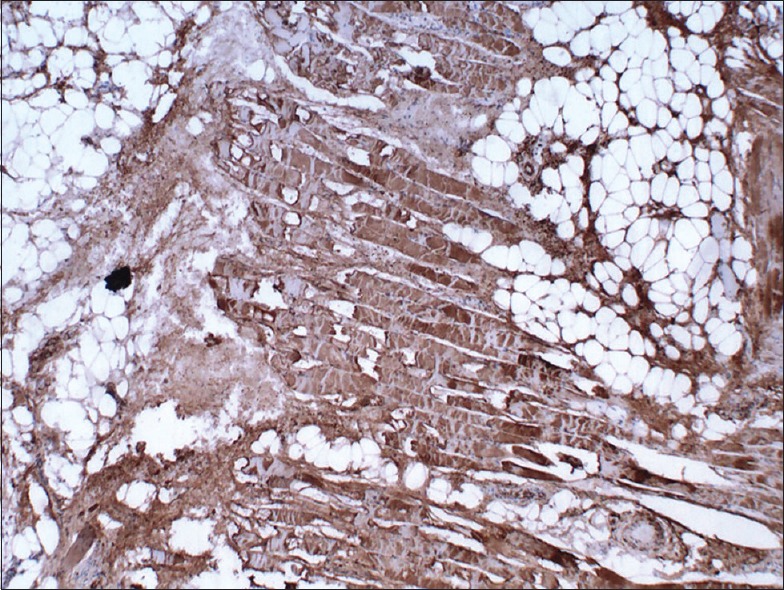

Histopathological examination of the excised specimen revealed large polygonal vacuolated cells with a granular cytoplasm and abundant glycogen that was positive for periodic acid-Schiff. The tissue stained positive for desmin and myoglobin [Figure 3]. These characteristic features confirmed the diagnosis of AR.

Figure 3.

Positive staining with desmin

Discussion

Extra-cardiac rhabdomyomas are extremely rare benign tumor of the skeletal muscle. The fetal type of rhabdomyoma usually presents at or below 3 years of age. AR mostly presents in the adult age group of 40 years and above. The occurrence is mainly in the head-and-neck region particularly floor of the mouth, soft palate, tongue, and buccal mucosa. The tumor is postulated to originate from the muscle component of the third and fourth brachial arches. Its cellular genesis is not definite but is most likely thought to be from primitive mesenchymal stem cells that undergo striated muscle differentiation.[2]

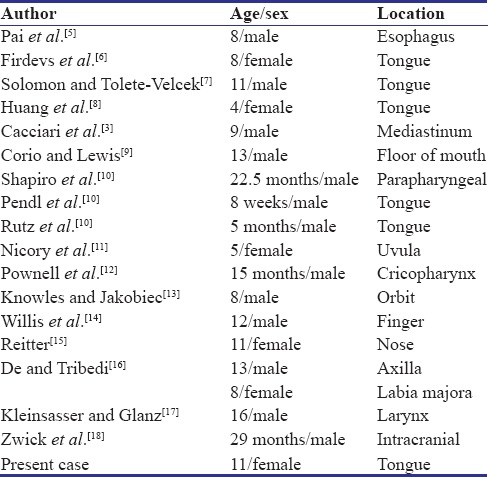

There are very few cases of solitary lingual ARs of childhood reported in the literature.[3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18] A comprehensive search in PubMed/MEDLINE database was done using MeSH terms such as “Adult Rhabdomyoma,” “Muscle tumor,” “Tongue,” “Benign” using various Boolean operators such as “AND” and “OR”. To the author's knowledge, till date, 18 cases of AR including the present have been found in the younger age group. Only 11 cases of this tumor have been described in infants and children up to 16 years reported in literature by Cacciari in 2001.[3] The age group in our review ranged from 8 weeks to16 years. The most common site of involvement is the head-and-neck region. Seven out of 18 cases occurred in the tongue showing a predilection toward the oral cavity. Male preponderance can be seen with 13 out of 17 cases occurring in males. They were all solitary lesions. Most were them were asymptomatic and were treated by simple excision [Table 1].

Table 1.

Summary of cases of adult rhabdomyoma in children

In the present case, the child recognized the presence of a mass in the tongue while swallowing. The slow growth did not allow the patient to realize the increase in size of the lesion. It presented as a single solitary mass on the lateral surface of the tongue. Clinically, this tumor is naïve in behavior unless its large size becomes a problem. This usually occurs in multifocal type. There have been reports of dyspnea due to the tumor.[2] They are solitary lesions but have been multifocal in 15% of cases.

Recognition of the tumor is demanding as the diagnosis is based on its distinctive histopathological appearance. Its presentation as a swelling of lateral border of the tongue should raise a high degree of suspicion. Its differential diagnosis includes granular cell tumor, hibernoma, reticulohistiocytoma, lymphoma, and most importantly rhabdomyosarcoma as the latter being more common. The most common site of rhabdomyosarcoma is in the peripheral skeletal musculature, and histologically, they display considerable polymorphism with atypical mitoses.

Macroscopically, it presents as a well-defined, rounded, unencapsulated intramuscular mass that shows characteristic texture and color of muscle. Histopathologically, it presents as striated muscle cells in various stages of differentiation and maturity.[1] It is composed of tightly packed, large, round, ovoid, or polygonal cell. A large number of which are vacuolated.[4] Occasionally, the granular appearance can lead to a misdiagnosis of granular cell tumor. Positive staining with desmin and myoglobin demonstrates immunochemically that the tumor cells are derived from muscle tissue[1] [Figure 3]. Negative staining with S-100 further substantiates exclusion of granular cellular tumor. No reports of anaplastic changes have been seen in any case.[3]

No spontaneous regression of the lesion is seen. Recurrences reported in literature were after a period of 1 month to 35 years with overall frequency of 16% and ascribed to incomplete removal of the tumor. The distinction between rhabdomyoma and malignant neoplasms, i.e. rhabdomyosarcoma, is of great significance to avoid aggressive excision and is not always very easy. A residual tumor may not only be a source of benign recurrences but also a source of cells with malignant potential.[5]

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Goldblum JR, Weiss SW, Folpe AL. Rhabdomyoma. Enzinger and Weiss's Soft Tissue Tumors. 5th ed. Philadelphia, Pa, USA: Mosby, Elsevier; 2008. pp. 583–94. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang GZ, Zhang GQ, Xiu JM, Wang XM. Intraoral multifocal and multinodular adult rhabdomyoma: Report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;70:2480–5. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cacciari A, Predieri B, Mordenti M, Ceccarelli PL, Maiorana A, Cerofolini E, et al. Rhabdomyoma of a rare type in a child: Case report and literature review. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2001;11:66–8. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-12191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zachariades N, Skoura C, Sourmelis A, Liapi-Avgeri G. Recurrent twin adult rhabdomyoma of the cheek. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1994;52:1324–8. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(94)90058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pai GK, Pai PK, Kamath SM. Adult rhabdomyoma of the esophagus. J Pediatr Surg. 1987;22:991–2. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(87)80490-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Firdevs V, Sina U, Burcu S. Adult type rhabdomyoma in a child. Oral Oncol Extra. 2006;42:213–6. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Solomon MP, Tolete-Velcek F. Lingual rhabdomyoma (adult variant) in a child. J Pediatr Surg. 1979;14:91–4. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(79)80586-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang X, Yang X, Wang Z, Li W, Jiang W, Chen X, et al. Adult rhabdomyoma of the tongue in a child. Pathology. 2012;44:51–3. doi: 10.1097/PAT.0b013e32834e42a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corio RL, Lewis DM. Intraoral rhabdomyomas. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1979;48:525–31. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(79)90299-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shapiro RS, Stool SE, Snow JB, Jr, Chamorro H. Parapharyngeal rhabdomyoma. Arch Otolaryngol. 1975;101:323–6. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1975.00780340055012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nicory C. Rhabdomyoma of the uvula: With a collection of cases of rhabdomyoma. Br J Surg. 1923;11:218–22. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pownell PH, Brown OE, Argyle JC, Manning SC. Rhabdomyoma of the cricopharyngeus in an infant. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1990;20:149–58. doi: 10.1016/0165-5876(90)90080-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knowles DM, 2nd, Jakobiec FA. Rhabdomyoma of the orbit. Am J Ophthalmol. 1975;80:1011–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(75)90330-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Willis J, Abdul-Karim FW, di Sant'Agnese PA. Extracardiac rhabdomyomas. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1994;11:15–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reitter GS. Rhabdomyoma of the nose. J Am Med Assoc. 1921;76:22–3. [Google Scholar]

- 16.De MN, Tribedi BP. Skeletal muscle tissue tumour. Br J Surg. 1940;28:17028. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kleinsasser D, Glanz H. Myogenic tumors of the larynx. Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1979;225:107–19. doi: 10.1007/BF00455211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zwick DL, Livingston K, Clapp L, Kosnik E, Yates A. Intracranial trigeminal nerve rhabdomyoma/choristoma in a child: A case report and discussion of possible histogenesis. Hum Pathol. 1989;20:390–2. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(89)90050-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]