Abstract

Human ageing is associated with decreased cellular plasticity and adaptability. Changes in alternative splicing with advancing age have been reported in man, which may arise from age-related alterations in splicing factor expression.

We determined whether the mRNA expression of key splicing factors differed with age, by microarray analysis in blood from two human populations and by qRT-PCR in senescent primary fibroblasts and endothelial cells. Potential regulators of splicing factor expression were investigated by siRNA analysis.

Approximately one third of splicing factors demonstrated age-related transcript expression changes in two human populations. Ataxia Telangiectasia Mutated (ATM) transcript expression correlated with splicing factor expression in human microarray data. Senescent primary fibroblasts and endothelial cells also demonstrated alterations in splicing factor expression, and changes in alternative splicing. Targeted knockdown of the ATM gene in primary fibroblasts resulted in up-regulation of some age-responsive splicing factor transcripts.

We conclude that isoform ratios and splicing factor expression alters with age in vivo and in vitro, and that ATM may have an inhibitory role on the expression of some splicing factors. These findings suggest for the first time that ATM, a core element in the DNA damage response, is a key regulator of the splicing machinery in man.

Keywords: Ageing, Splicing, SRSF, hnRNP, Human

1. Introduction

Ageing is characterised by a generalised decrease of plasticity of cellular processes within tissues, including in tissue repair, immune repertoire and cognitive function (Wang et al., 2011; Asumda and Chase, 2011). Ageing is also associated with many common chronic diseases in the human population (Harman, 1991). The ageing process is however complex and heterogeneous, with some people surviving free of disease until advanced ages, whilst others become prematurely frail. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified variants that account for approximately one third of the variability in lifespan, so other factors must underpin the differences between people in how well they age (Harries et al., 2012a). Genomics, rather than genetics, may prove a key focus to identify the mechanisms involved in determining successful ageing (Kulminski and Culminskaya, 2013). Accordingly, gene expression analyses have already proven useful in the study of some age-related conditions such as cognitive impairment and decrease in muscle function in the elderly (Pilling et al., 2012; Harries et al., 2012b).

In a recent large-scale human population based study, we identified that a focussed set of transcripts and biological pathways show robust alterations in expression in leukocytes in vivo with advancing age, and that the majority of these pathways control messenger RNA splicing processes (Harries et al., 2011). These changes were also accompanied by alterations in the ratios of alternatively expressed transcripts. Deregulation of splicing with age has also been suggested to occur in some animal species (Yannarell et al., 1977; Meshorer and Soreq, 2002). In man, alternative splicing of the LMNA gene has been implicated in human ageing models; Mutations in LMNA that cause the skipping of exon 11 result in the monogenic Hutchinson Gifford Progeria syndrome (Cao et al., 2011), but low levels of the progerin isoform, which increase with age, have also been demonstrated in older humans (Graziotto et al., 2012). Other than this observation, there has to date been little systematic evaluation of the effect of ageing on the milieu of splicing variants in other genes.

Messenger RNA (mRNA) splicing is a co-transcriptional process where the initial RNA transcript (the hnRNA or primary RNA transcript) is modified to remove the non-coding introns, and to include the vital 5′ and 3′ regulatory regions (Cartegni et al., 2002; Dujardin et al., 2013). Up to 95% of all genes are alternatively spliced, enabling one gene to code for multiple proteins, which can have different spatial or temporal expression profiles, and differing or even opposing functions (Pan et al., 2008). The consequence of alternative splicing is to enhance the diversity and complexity of the proteome (Graveley, 2001) and to help cells specialise for tissue-specific functions. Alternative splicing also influences the ability of an organism to react and adapt to its environment; it is therefore a major player in the determination of cellular plasticity. Alternative splicing, like constitutive splicing, is regulated by a series of conserved, core, regulatory sequence elements; the splice donor site, the splice acceptor site, the branch site and the polypyrimidine tract. However, for alternatively spliced transcripts, the consensus sequence is essential, but not always sufficient, for splice site usage. Auxiliary splice site elements (exon and intron splicing enhancers and silencers) are often required to add an additional layer of regulation (Cartegni et al., 2002). These regulatory elements can work by binding a set of splicing regulator proteins; serine/arginine-rich splicing factor (SRSF) proteins, which promote exon inclusion and heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (hnRNPs), which usually inhibit cassette exon inclusion (Smith and Valcárcel, 2000). The role of SRSFs and hnRNPs are not exclusive to splicing, SRSFs are involved in several other features of mRNA biology including translation, nonsense-mediated decay and mRNA export (Kervestin and Jacobson, 2012; Hocine et al., 2010). These proteins can act antagonistically and in some cases can have the opposite effects (Caceres and Kornblihtt, 2002).

There are several factors which could influence splice site usage during human ageing. It is possible that accumulated DNA damage to the sequences of the core or auxiliary splicing factor binding sites has the potential to cause splicing alterations with age, but such effects would be cell-specific and heterogeneous, and therefore unlikely to produce a measurable difference in the level of any particular isoform in a mixed population of cells. However, our previous data suggests that age-related deviations from normal splicing patterns may instead be due to altered expression of the factors (splicing enhancers and silencers) that bind these sequences (Harries et al., 2011). Therefore, in this study, we aimed to use a combination of in vivo mRNA expression analyses in two populations, in vitro cell senescence experiments and targeted knockdown of key genes to identify potential molecular mechanisms that could affect the mRNA expression of core and regulatory splicing factors in man.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study cohorts

We used microarray data from two separate human populations, the InCHIANTI study and the San Antonio Family Heart Study. The InCHIANTI study is a large longitudinal study of individuals living in the Chianti region of Tuscany (Ferrucci et al., 2000). The microarray dataset comprises expression data on 16,571 transcripts expressed in peripheral blood from 695 subjects aged 30–104 years (Harries et al., 2011). Blood was collected into PAXgene tubes (BD Biosciences), and extracted using the PAXgene blood RNA kit (Qiagen, Paisley, UK). Microarray analysis was carried out on the Illumina HT-12 array (Illumina, San Diego, USA). The second population, the San Antonio Family Heart Study (SAFHS), comprises 1238 individuals of Mexican ancestry aged from 15 to 94 years (Goring et al., 2007), with publicly-available expression data from 14,727 transcripts in isolated lymphocytes. Participant characteristics have been described (Harries et al., 2012a; Mitchell et al., 1994). All microarray experiments and analyses complied with MIAME guidelines.

2.2. Choice of splicing factor and splicing regulator transcripts for analysis

We identified transcripts encoding components of the core splicing machinery and known splicing regulators by reference to splicing factor databases (http://rulai.cshl.edu/cgi-bin/SpliceFac/). The presence of each transcript in the microarray expression data from each population was assessed by a search of Human Genome Organization Gene Nomenclature Committee (HGMC) gene identifiers (www.genenames.org) prefixed with the following character strings; “HNRNP”, “IMP”, “LSM”, “RRP”, “SF3”, “SNRNP”, “U2” or “SFR”, indicative of core or auxiliary splicing factors. We identified a list of 71 splicing factors or regulators for analysis, for which microarray expression data were available in the InCHIANTI dataset. The target list comprised of hnRNPs (usually splice site inhibitors), SRSFs (usually splice site activators), as well as some of the core spliceosomal proteins involved in constitutive splicing. Of the 71 splicing-related transcripts expressed in the InCHIANTI data, 55 transcripts were also represented in the SAFHS microarray data (see supplementary Table 3 for a full list of genes included in each analysis and supplementary Table 4 for transcript and microarray probe identifiers).

2.3. Correlation of splicing factor expression with age in human populations

Statistical associations between the expression level of each test transcript and age were tested using fully adjusted multivariate adjusted linear regression models (R Statistical Computing Language v2.14.0), with logged expression data as the outcome variable. InCHIANTI regression models were adjusted for sex, waist-circumference (cm), social-status (highest education level attained, five categories: none, elementary, secondary, high-school and university/professional), pack-years smoked (five categories: none, <20 years, 20–39 years, >40 years, and missing), study site ([Greve] or [Bagno a Ripoli]), batch effects (amplification and hybridization), and the proportion of leukocyte sub-type in the blood (lymphocytes, monocytes, neutrophils and eosinophils). SAFHS regression models were adjusted for sex and smoking-status, as data on these factors alone were available. We accounted for multiple testing using false discovery rate (FDR – package “fdrtool” (Strimmer, 2008)) adjusted p-values (q-values), using the conventional cut-off of q < for statistical significance. Separate regression screens were performed for each cohort.

2.4. Assessment of core or regulatory role of differentially expressed splicing factors

The splicing factors which were analysed with age in the INCHIANTI and SAFHS population were divided into two groups, those demonstrating a significant association with age in the fully adjusted model (q = <0.05), and those not. Splicing factors were identified as being “core” (i.e. part of the constitutive spliceosome) or “regulatory” (i.e. hnRNP-related splicing inhibitory transcripts or SRSF-related activating transcripts). Differences in the distribution of “core” and “regulatory” splicing factors between the ‘significant’ and ‘non-significant’ transcript sets were assessed using χ2 test.

2.5. In vitro senescence

2.5.1. Senescence of human primary cell lines in vitro

To examine the relationship between splicing factor expression and cellular ageing without any of the confounding factors associated with epidemiological studies, we carried out in vitro senescence of two primary cell types, human aortic endothelial cells (HAOEC) and normal human dermal fibroblast cells (nHDF), which have been reported as undergoing cellular senescence by different processes (Shelton et al., 1999). Cells were purchased from Promocell, Heidelburg, Germany. Endothelial cells were isolated from the human abdominal and thoracic aorta and fibroblasts were derived from human skin taken from the thigh. Cells were tested for the presence of mycoplasma at source and also for cell type specific markers to confirm identity and both cell types were at passage 2 after thawing which corresponds to less than 15 population doublings. Three independent cultures underwent in vitro senescence by repeated culture until growth arrest as biological replicates for each cell type. Culture media included 1% penicillin and streptomycin and a cell-specific supplement mix: fibroblasts – foetal calf serum 0.03 ml/ml, recombinant fibroblast growth factor 1 ng/ml and recombinant human insulin 5 μg/ml; and endothelial cells–foetal calf serum 0.05 ml/ml, endothelial cell growth supplement 0.004 ml/ml, epidermal growth factor 10 ng/ml, hydrocortisone 1 μg/ml, heparin 90 mg/ml). Cells were cultured in humidified incubators at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Cells were cultured until they reached 80–90% confluence serially until the cells reached growth arrest.

2.5.2. Biochemical, molecular and morphological assessment of cell senescence

Cell senescence was assessed by population doubling times, qualitative assessment of morphological changes and staining for senescence-associated β-galactosidase activity (Sigma Aldrich, UK) following the methods previously described (Dimri et al., 1995). Expression of the CDKN2A and VEGFA genes was also measured by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR), by TaqMan Low Density Array (TLDA) on the ABI Prism 7900HT platform, as molecular markers of cell senescence (assay identifiers available on request). Real-time PCR conditions are described in detail below. Cells were considered senescent two to four passages prior to absolute growth arrest, when molecular and biochemical assessment indicated senescence, but whilst the cultures were still capable of division and did not exhibit signs of cellular stress.

2.5.3. Expression profiling of splicing factor expression in in vitro senesced cells

Splicing factor transcripts were selected for inclusion on the TLDA card based on evidence from our microarray screen of age-associated expression. Most of the transcripts selected encoded splicing regulatory proteins (hnRNPA0, hnRNPA1, SRSF1, SRSF6) although some core spliceosomal proteins (including LSM14A, IMP2 and LSM2) were included. A full list of the assay identifiers and the reference sequences of the mRNAs they detect is given in supplementary Table 5. The endogenous controls were IDH3B, GUSB and PPIA which were selected based on empirical evidence for a lack of association with age in the microarray data (Harries et al., 2011).

RNA was extracted from endothelial cells and fibroblasts at early and late passage using the Qiagen RNA extraction kit (Qiagen, West Sussex, UK), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Total RNA (100 ng) was reverse transcribed in 20 μl reactions using the Superscript III VILO kit (Life Technologies, Foster City, USA) prior to TaqMan Low Density Array (TLDA) analysis. Quantitative RT-PCR reactions were performed on the ABI 7900HT platform (Life Technologies, Foster City, USA). Cycling conditions were 50 °C for 2 min, 94.5 °C for 10 min and 40 cycles of 97 °C for 30 s and 57.9 °C for 1 min. The reaction mixes included 50 μl TaqMan® Fast Universal PCR Mastermix (no AmpErase® UNG) (Life technologies, Foster City, USA), 30 μl dH2O and 20 μl cDNA template. 100 μl reaction solution was dispensed into the TLDA card chamber and centrifuged twice for 1 min at 1000 rpm to ensure distribution of solution to each well. The gene expression of each sample was measured in triplicate in “young” and “old” cells. The comparative Ct technique was used to calculate the expression of each test transcript (Pfaffl, 2001). Expression was assessed relative to the mean of the three endogenous controls IDH3B, PPIA and GUSB with normalisation back to the mean value for the transcript in the early passage cells in each case. Mann–Whitney-U analysis was used to test statistical significance of expression differences between early and late passage cells. All statistical analyses were carried out using STATA v12.0 (StataCorp LP, Texas, USA).

2.5.4. Analysis of alterations in isoform expression for known ageing related genes

As a measure of downstream consequences of alterations in splicing factor expression in senescent cells, we measured the ratio of alternatively expressed isoforms of a small panel of genes known to be important in ageing or to have altered expression with age. These included the known age-related genes CDKN2A (Krishnamurthy et al., 2006), VEGF (Ryan et al., 2006), TERT (Tomas-Loba et al., 2008), as well as the EFNA1, GPR18 and VCAN genes, which we demonstrated to exhibit alterations in isoform ratios during human ageing in peripheral blood in our previous study (Harries et al., 2011). Transcript and assay details are given in supplementary Table 6). Expression profiling was carried out on the TLDA platform as described earlier, with isoform ratio changes examined for statistical significance by Mann–Whitney-U analysis of the isoform expression ratios in ‘young’ and ‘old’ cells.

2.6. Epidemiological investigation of potential regulators of splicing factor expression

To identify other transcripts in the genome with a potential role in the regulation of splicing factor expression, we carried out a transcriptome-wide, fully-adjusted multivariate regression analysis to identify transcripts associated with age itself, and also with the expression of two of the most deregulated splicing regulator transcripts SRSF6 and hnRNPA0. Models were adjusted as described in the sections above.

2.7. Assessment of ATM transcript levels in senescent cells

We measured the expression levels of the ATM transcripts encoding a key component of the DNA damage response in both endothelial cells and in fibroblasts by qRT-PCR. cDNA was produced as described above, using the Superscript III VILO kit (Life Technologies, Foster City, USA) and qRT-PCR reactions were carried out in triplicate in 96 well plates in 10 μl volumes. Reactions contained 5 μl TaqMan Fast Universal Mastermix (no AMPerase) (Life Technologies, Foster City USA), 0.25 μM probe and 2 μl cDNA reverse transcribed as above in a total volume of 10 μl. PCR conditions were a single cycle of 95 °C for 20 s followed by 50 cycles of 95 °C for 1 s and 60 °C for 20 s. The probes to each transcript comprised a pre-validated off-the-shelf assay provided by Life Technologies (Foster City USA); Assay identification number available on request). The relative expression level of each transcript was then determined relative to the GUSB and GAPDH endogenous control and normalised to the level of each transcript in the low passage cells.

2.8. In vitro knockdown of ATM expression in early passage fibroblasts

The knock-down of ATM in passage 9 fibroblasts was carried out using Silencer® Select siRNAs from Ambion® (Life Technologies, Foster City, USA) s57221 for knockdown of ATM reference sequence NM_000051.3 (silencer s577300). Silencer® select negative and GAPDH positive control siRNA were used to determine knock down as well as a normal control sample. We performed the knockdowns with NHDF Nucleofector1 Kit (Lonza, Switzerland) as per the manufacturer’s instructions with 30 mM, 100 mM or 300 mM of Silencer® siRNA to optimise gene knockdown. Two separate siRNAs were used for validation.

5 × 10+4 fibroblasts cells were resuspended in 100 μl nucleofection solution (Lonza, Switzerland) and fibroblasts were transferred into the nucleofection cuvette containing scrambled siRNA, GAPDH siRNA or no silencer. Following the short electroporation (programme P-022 for Nucleofector® device), 100 μl culture medium was added to the electroporated fibroblasts, transferred into a 6-well plate and incubated for 48 h. RNA was extracted from electroporated fibroblasts using the mirVana™ miRNA Isolation Kit (Life Technologies, Foster City, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. A Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific Ltd, Wilmington, USA) was used to quality control RNA and RNA was only accepted for analysis if the concentration was >30 ng/μl. Total RNA (100 ng) was reversed transcribed in 20 μl reactions using the Superscript III VILO kit (Life Technologies, Foster City USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. ATM knockdown in the primary fibroblast cells was assessed by measuring the levels of ATM probes Hs00175892_m1 and Hs01112307_m1 which detect ATM reference sequence NM_000051.3 (life technologies, Foster City, USA). The expression of ATM siRNA treated samples were assessed (as per the assessment of ATM expression in senescent cells) relative to the GAPDH endogenous control and normalised to the level of ATM transcripts in the negative and normal controls. Knockdown of the ATM transcripts was confirmed by qRT-PCR carried out on each sample in triplicate using probes specific to the ATM transcript on the ABI Prism 7900HT platform (Life Technologies, Foster City, USA).

2.9. Assessment of splicing factor expression following siRNA-mediated knockdown of ATM transcripts

RNA from the cells in which we had confirmed ATM transcript knockdown was then used to assess splicing factor mRNA transcript expression using the TLDA approach as described in previous sections. Splicing factor transcript expression results in from the ATM siRNA treated fibroblasts was compared with both untreated cells, and with cells treated with the scrambled control to ensure that any differences noted derived from the specific knockdown and not from manipulation of cells. Differences in splicing factor mRNA expression between ATM knockdown and control cells were examined for statistical significance using Mann–Whitney-U test.

3. Results

3.1. Differences in splicing factor expression are associated with age in two human populations

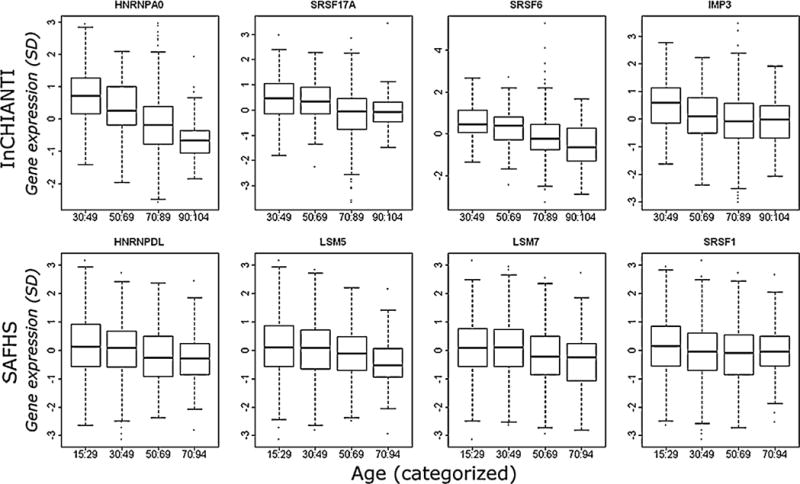

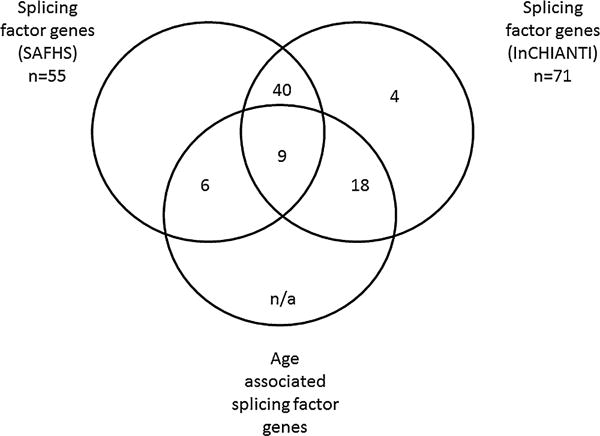

We identified that 27/71 (38%) splicing proteins tested were significantly associated with age following adjustment for multiple testing in the INCHIANTI microarray dataset, with 15/55 (29.4%) transcripts being significantly associated with age in SAFHS (Table 1). Fig. 1 shows histograms for the most age-associated splicing transcripts in the InCHIANTI and SAFHS cohorts. All age-associated transcripts were down-regulated with the exception of SFRS14, SRSF3 and SRSF11 in the InCHIANTI dataset and SRSF14, RALY and HNRNPAB in SAFHS. 51 transcripts were common to both datasets (Table 1 and supplementary Table 3), of which 9 (SRSF1, SRSF6, LSM5, LSM2, SRSF14, SF3B1, HNRNPAB, HNRNPD and HNRNPH3) were significantly associated with age in both populations (Table 1). Fig. 2 shows the overlap of the age-associated splicing factor expressions in the InCHIANTI and SAFHs cohorts.

Table 1.

The association of splicing factor gene expression with advancing age in the InCHIANTI and SAFHS populations (n = 695 and n = 1238 respectively) is given. Associations with age are calculated by logistic regression with adjustment for confounding factors. The gene and probe identities are given; the significant p value, coefficient and the false discovery Rate (FDR) adjusted q-value are given. Genes demonstrating an association with age at the level of q = 0.05 are given in bold, underlined font in both cases. Genes significantly associated with age in both datasets are indicated with a star.

| InCHIANTI

|

SAFHS

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene ID | Probed | p-Value | Coefficient | q-Value | Gene ID | Probed | p-Value | Coefficient | q-Value |

| HNRNPA0 | ilmn_1753279 | <0.001 | −0.002 | <0.001 | HNRNPDL | gi_14110406a | <0.001 | −0.010 | <0.001 |

| SRSF17A | ilmn_2117716 | <0.001 | −0.002 | <0.001 | LSM5* | gi_6912487s | <0.001 | −0.010 | <0.001 |

| SRSFS6* | ilmn_1697469 | <0.001 | −0.003 | <0.001 | LSM7 | gi_7706422s | <0.001 | −0.008 | <0.001 |

| IMP3 | ilmn_1733696 | <0.001 | −0.002 | <0.001 | SRSF1* | gi_31543618s | <0.001 | −0.007 | <0.001 |

| SRSF18 | ilmn_2161357 | <0.001 | −0.001 | <0.001 | LSM2* | gi_34013512s | <0.001 | −0.006 | 0.001 |

| HNRNPA1 | ilmn_1661346 | <0.001 | −0.002 | <0.001 | HNRNPH3* | gi_14141158a | 0.002 | −0.005 | 0.006 |

| HNRNPD* | ilmn_2321451 | <0.001 | −0.003 | 0.001 | SRSF14* | gi_38490530s | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.006 |

| SRSF1* | ilmn_1795341 | <0.001 | −0.002 | 0.001 | SRSF6* | gi_38158029s | 0.002 | −0.005 | 0.006 |

| HSSG1 | ilmn_1778836 | <0.001 | −0.001 | 0.001 | LSM3 | gi_7657314s | 0.004 | −0.005 | 0.009 |

| SRSF10 | ilmn_1742798 | <0.001 | −0.002 | 0.002 | HNRNPR | gi_14141188s | 0.005 | −0.005 | 0.009 |

| HNRNPM | ilmn_1805371 | <0.001 | −0.001 | 0.003 | SF3B1* | gi_6912653s | 0.005 | −0.005 | 0.010 |

| HNRNPH3* | ilmn_1654920 | 0.001 | −0.001 | 0.004 | RALY | gi_21396479a | 0.007 | 0.005 | 0.013 |

| LSM5* | ilmn_1737947 | 0.001 | −0.001 | 0.005 | HNRNPD* | gi_14110413a | 0.010 | −0.004 | 0.016 |

| LSM2* | ilmn_2070300 | 0.001 | −0.001 | 0.005 | HNRNPAB* | gi_14110401a | 0.019 | 0.004 | 0.029 |

| HNRNPUL2 | ilmn_1810327 | 0.002 | −0.001 | 0.007 | HNRNPH1 | gi_5031752s | 0.032 | −0.004 | 0.045 |

| LSM14A | ilmn_2079803 | 0.003 | −0.001 | 0.008 | SRSF8 | gi_23111063a | 0.039 | −0.003 | 0.052 |

| SRSF14* | ilmn_1689007 | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.008 | SRSF12 | gi_21040254s | 0.043 | −0.003 | 0.056 |

| HNRNPK | ilmn_2378048 | 0.003 | −0.002 | 0.008 | SRSF3 | gi_31377552s | 0.048 | −0.003 | 0.060 |

| SRSF2 | ilmn_1696407 | 0.004 | −0.002 | 0.011 | SF3A3 | gi_5803166s | 0.057 | −0.003 | 0.067 |

| SRSF5 | ilmn_2378868 | 0.006 | −0.002 | 0.015 | LSM8 | gi_21314665s | 0.059 | −0.003 | 0.069 |

| SRSF3 | ilmn_1723212 | 0.006 | 0.000 | 0.015 | SRSF10 | gi_4759097s | 0.087 | −0.003 | 0.094 |

| SRSF11 | ilmn_1657790 | 0.008 | 0.000 | 0.018 | HNRNPA2B1 | gi_14043073a | 0.103 | −0.003 | 0.107 |

| HNRNPA2B1 | ilmn_1886493 | 0.008 | −0.001 | 0.019 | SRSF16 | gi_5902129s | 0.108 | 0.003 | 0.111 |

| U2AF2 | ilmn_1768930 | 0.010 | −0.001 | 0.023 | SRSF2 | gi_4506898s | 0.138 | 0.003 | 0.133 |

| SF3B1* | ilmn_1706075 | 0.014 | −0.002 | 0.029 | HNRNPK | gi_14165436a | 0.174 | −0.002 | 0.155 |

| HNRNPAB* | ilmn_1651262 | 0.022 | −0.001 | 0.041 | LSM10 | gi_14249631s | 0.178 | 0.002 | 0.158 |

| SRSF9 | ilmn_1760683 | 0.023 | −0.001 | 0.043 | HNRPL | gi_4557644s | 0.181 | 0.002 | 0.160 |

| SRSF8 | ilmn_1692575 | 0.031 | 0.000 | 0.053 | HNRNPA1 | gi_4504444a | 0.192 | −0.002 | 0.165 |

| SF3A1 | ilmn_1697286 | 0.036 | 0.000 | 0.059 | LSM6 | gi_5901997s | 0.218 | −0.002 | 0.179 |

| SRSF2IP | ilmn_1830806 | 0.036 | 0.000 | 0.059 | SRSF2IP | gi_4759171s | 0.236 | −0.002 | 0.187 |

| HNRNPH2 | ilmn_1781764 | 0.037 | 0.000 | 0.060 | HNRNPUL1 | gi_21536323a | 0.264 | 0.002 | 0.200 |

| HNRNPF | ilmn_1668179 | 0.040 | 0.000 | 0.062 | HNRNPM | gi_14141151i | 0.305 | 0.002 | 0.218 |

| SNRNP27 | ilmn_2069945 | 0.041 | 0.000 | 0.063 | SRSF4 | gi_34147660s | 0.306 | 0.002 | 0.219 |

| SRSF15 | ilmn_1659874 | 0.048 | 0.000 | 0.069 | HNRNPC | gi_14110430a | 0.329 | −0.002 | 0.228 |

| SRSF12 | ilmn_2373266 | 0.054 | 0.000 | 0.074 | IMP4 | gi_15529981s | 0.332 | −0.002 | 0.229 |

| LSMD1 | ilmn_1691131 | 0.064 | 0.000 | 0.084 | SF3B3 | gi_40254848s | 0.335 | −0.002 | 0.230 |

| SNRNP48 | ilmn_1754304 | 0.078 | 0.000 | 0.098 | SF3A1 | gi_34147572s | 0.342 | 0.002 | 0.234 |

| SNRNP25 | ilmn_1801118 | 0.087 | 0.000 | 0.107 | SF3A2 | gi_32189413s | 0.425 | −0.001 | 0.275 |

| HNRNPC | ilmn_2334587 | 0.089 | 0.000 | 0.109 | U2AF1 | gi_5803206s | 0.439 | 0.001 | 0.281 |

| HNRNPA3 | ilmn_1703369 | 0.103 | 0.000 | 0.122 | HNRNPM | gi_14141153a | 0.457 | 0.001 | 0.289 |

| LSM12 | ilmn_2092693 | 0.108 | 0.000 | 0.126 | HNRNPAB | gi_14110403i | 0.557 | 0.001 | 0.332 |

| LSM6 | ilmn_1675462 | 0.127 | 0.000 | 0.140 | LSM1 | gi_7657312s | 0.566 | 0.001 | 0.335 |

| HNRNPH1 | ilmn_2101920 | 0.133 | 0.000 | 0.145 | SF3B4 | gi_23111059s | 0.701 | 0.001 | 0.384 |

| SNRNP35 | ilmn_2395285 | 0.135 | 0.000 | 0.146 | HNRNPU | gi_14141160a | 0.767 | −0.001 | 0.406 |

| SF3B4 | ilmn_1722648 | 0.137 | −0.001 | 0.147 | HNRNPA3 | gi_34740328s | 0.817 | 0.000 | 0.422 |

| SF3B3 | ilmn_1803110 | 0.152 | 0.000 | 0.158 | SRSF11 | gi_23111060s | 0.843 | 0.000 | 0.429 |

| HNRNPU | ilmn_2370135 | 0.172 | 0.001 | 0.174 | U2AF2 | gi_6005925s | 0.848 | 0.000 | 0.430 |

| SF3A3 | ilmn_1705151 | 0.204 | −0.001 | 0.199 | HNRPF | gi_14141150s | 0.850 | 0.000 | 0.431 |

| SNRNP200 | ilmn_1705928 | 0.225 | 0.000 | 0.213 | SRSF15 | gi_40789228s | 0.858 | 0.000 | 0.434 |

| SNRNP70 | ilmn_1732053 | 0.229 | −0.001 | 0.217 | SRSF5 | gi_40254839s | 0.890 | 0.000 | 0.442 |

| U2AF1L4 | ilmn_1779177 | 0.271 | 0.000 | 0.244 | HNRNPA0 | gi_14110425s | 0.940 | 0.000 | 0.456 |

| LSM4 | ilmn_1788099 | 0.278 | 0.000 | 0.249 | SF3B5 | gi_42740890s | 0.943 | 0.000 | 0.457 |

| SRSF16 | ilmn_2146566 | 0.282 | 0.000 | 0.251 | SRSF9 | gi_38016912s | 0.962 | 0.000 | 0.462 |

| SRSF4 | ilmn_2175075 | 0.300 | −0.001 | 0.262 | LSM4 | gi_33620778s | 0.986 | 0.000 | 0.468 |

| RRP8 | ilmn_2066667 | 0.301 | 0.000 | 0.263 | SF3B2 | gi_37541034s | 0.990 | 0.000 | 0.469 |

| SF3B14 | ilmn_2182120 | 0.348 | 0.000 | 0.291 | |||||

| HNRNPUL1 | ilmn_2395728 | 0.361 | 0.000 | 0.299 | |||||

| LSM7 | ilmn_1678165 | 0.414 | 0.000 | 0.329 | |||||

| U2AF1 | ilmn_1772113 | 0.433 | 0.000 | 0.339 | |||||

| LSM3 | ilmn_2229242 | 0.535 | 0.000 | 0.388 | |||||

| LSM10 | ilmn_1751803 | 0.553 | 0.000 | 0.395 | |||||

| RRP9 | ilmn_1689972 | 0.556 | 0.000 | 0.397 | |||||

| LSM1 | ilmn_2218450 | 0.571 | 0.000 | 0.403 | |||||

| LSM8 | ilmn_1805590 | 0.584 | 0.000 | 0.409 | |||||

| IMP4 | ilmn_2156982 | 0.594 | 0.000 | 0.412 | |||||

| HNRNPL | ilmn_2389582 | 0.669 | 0.000 | 0.442 | |||||

| SNRNP40 | ilmn_1799814 | 0.708 | 0.000 | 0.456 | |||||

| SF3A2 | ilmn_1754220 | 0.710 | 0.000 | 0.456 | |||||

| HNRNPR | ilmn_2175894 | 0.752 | 0.000 | 0.471 | |||||

| SF3B2 | ilmn_1775939 | 0.818 | 0.000 | 0.492 | |||||

| SF3B5 | ilmn_1689389 | 0.991 | 0.000 | 0.539 | |||||

Fig. 1.

Box plots showing the relationship between gene expression levels and increasing age in the InCHIANTI and SAFHS populations. Standardised gene expression levels relative to the endogenous controls are shown on the Y-axis and the population age groups are shown on the X-axis. These are the top four splicing factor gene expression changes with age in the InCHIANTI and SAFHs populations.

Fig. 2.

Venn diagram indicating gene expression transcripts associated and unassociated with age in the two population cohorts, SAFHS and InCHIANTI. The mRNA transcripts with the same associations in both populations are also identified.

3.2. Splicing regulator transcripts are more likely than core splicing factor transcripts to be associated with age in the InCHIANTI dataset

Transcripts coding for regulators of splicing were significantly more likely to be associated with age than core spliceosomal RNAs in the InCHIANTI cohort. In the significantly associated set of transcripts, 74% of mRNA transcripts coded for splicing regulatory proteins rather than core spliceosomal components, whereas in the non-significant group, only 34% of transcripts encode splicing regulators, which was significant at the level of p = 0.001 as assessed by χ2 squared test. However, in the SAFHS microarray data (with 55 vs. 71 genes testable in InCHIANTI), we did not note any preponderance of splicing regulator transcripts in the age-associated dataset (p = 0.907839).

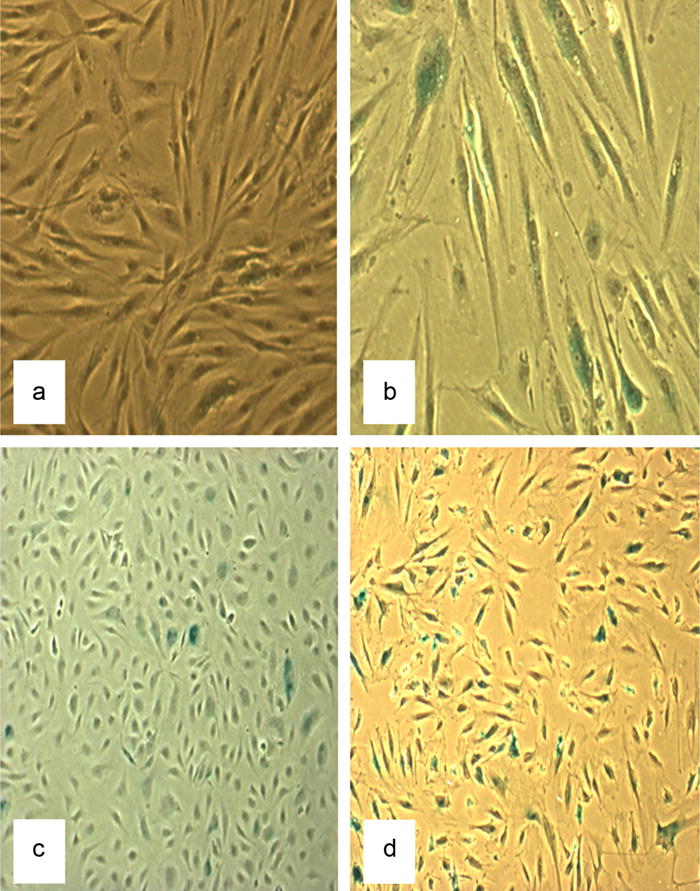

3.3. Primary fibroblasts and primary endothelial cells undergo replicative senescence at different rates

We achieved molecular, biochemical and cell morphology parameters consistent with cellular senescence for both fibroblasts and endothelial cells in vitro (Table 2). Senescence was accompanied by increased β-galactosidase staining, a biochemical marker of cellular senescence (Dimri et al., 1995), and alterations in morphology and population doubling time were recorded in both cell types (Table 2). Fibroblasts ceased growth at passage (p) 22, corresponding to approximately 53 cell doublings whilst endothelial cells ceased growth at (p) 15, corresponding to 35 cell doublings. Both cell types had a slower population doubling time with increasing senescence, endothelial cells reached confluence within 3 days in the early passages increasing to 10 days in the latest passage and fibroblasts slowed from 4 to 27 days. Splicing factor and isoform expression was therefore assessed at p7: for both cell types (termed “young” cells): PD = 21 in endothelial cells and PD = 23 in fibroblasts, and at p13 (PD = 33) in endothelial “older” cells and p18 (PD = 45) in fibroblast “old” cells. We excluded terminally senescent cells from our analyses in order to ensure that we were examining senescence, rather than stress response changes. β-Galactosidase staining was visibly present in 68% of the endothelial cells at p13 and 58% of the fibroblasts at p18 (Fig. 2).

Table 2. Molecular markers of cell senescence in young and old fibroblasts and endothelial cells.

The change in the expression of age-related genes VEGFA and CDKN2A in fibroblasts and endothelial cells is given for “young” (passage = 7) and “old” fibroblasts (passage = 18) and endothelial cells (passage = 13). Differences in transcript expression levels were assessed by Mann–Whitney U analysis. The staining percentage of β-galactosidase marker of senescence is given for each passage. PD = population doubling and PDT = population doubling time in hours.

| Fibroblasts

|

Endothelial cells

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p7 | p18 | p7 | p13 | |

| β-gal (%) | 4% | 58% | 7% | 68% |

| z | p | z | p | |

| VEGFA | 3.703 | 0.0002 | 4.157 | 0.0002 |

| CDKN2A | −2.842 | 0.0045 | −2.242 | <0.001 |

| PD | 23 | 45 | 21 | 33 |

| PDT (hours) | 72.041 | 120.06 | 36.02 | 240.139 |

3.4. Splicing factor expression demonstrates age-related changes in senescing primary cell cultures

We identified that the expression level of all 20 of the selected splicing regulatory factors were significantly associated with age in fibroblasts (see Table 3). All splicing factors and regulators were expressed at significantly lower levels in older fibroblasts with the exception of HNRNPUL2, PNISR and SF3B1, which demonstrated higher expression in older cells. Senescence-associated differences in the expression of splicing factor transcripts was evident in endothelial cells, although not as comprehensively; only 9 of the 20 transcripts analysed were associated with age in endothelial cells, and several of these were positively, rather than inversely, correlated with age (Table 3). Representative box plots of the top three most associated splicing factors for fibroblasts (PNISR, hnRNPA1 and hnRNPA2B1) and endothelial cells (hnRNPK, hnRNPM and hnRNPUL2), are given in Fig. 3.

Table 3. Expression of core splicing factor and splicing regulator transcripts in cells senesced in vitro.

Gene expression measurements were taken for twenty core splicing factor or splicing regulator genes in two cell populations (primary endothelial cells and fibroblasts). Gene expression between old and young passage cells (p7 and p13 in endothelial cells; p7 and p18 in fibroblasts) was assessed. Effect size and direction is given by z scores (standard deviation from the mean), p-values were determined by Mann–Whitney U analysis.

| Fibroblasts

|

Endothelial cells

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | z | p-value | z | p-value |

| AKAP17A | 3.926 | 0.0001 | −2.771 | 0.0056 |

| HNRNPA0 | 3.349 | 0.0008 | −0.924 | 0.3556 |

| HNRNPA1 | 4.157 | <0.0001 | −2.194 | 0.0282 |

| HNRNPA2B1 | 4.157 | <0.0001 | −1.097 | 0.2727 |

| HNRNPD | 4.041 | 0.0001 | 0.000 | 1.0000 |

| HNRNPH3 | 3.522 | 0.0004 | 0.173 | 0.8625 |

| HNRNPK | 3.753 | 0.0002 | −3.811 | 0.0001 |

| HNRNPM | 2.771 | 0.0056 | −4.041 | 0.0001 |

| HNRNPUL2 | −3.060 | 0.0022 | −4.041 | 0.0001 |

| IMP3 | 3.291 | 0.0010 | −3.753 | 0.0002 |

| LSM14A | 3.002 | 0.0027 | −3.464 | 0.0005 |

| LSM2 | 2.078 | 0.0377 | 1.848 | 0.0647 |

| PNISR | −4.157 | <0.0001 | 2.714 | 0.0067 |

| SF3B1 | −2.078 | 0.0377 | 1.559 | 0.1190 |

| SRSF1 | 3.522 | 0.0004 | −0.981 | 0.3263 |

| SRSF2 | 3.984 | 0.0001 | 0.231 | 0.8174 |

| SRSF3 | 3.522 | 0.0004 | 1.097 | 0.2727 |

| SRSF6 | 3.637 | 0.0003 | −1.328 | 0.1842 |

| SRSF7 | 4.157 | <0.0001 | 3.291 | 0.0010 |

| TRA2B | 4.041 | 0.0001 | −0.058 | 0.9540 |

Fig. 3.

The figures show β-galactosidase activity as a marker of cellular senescence. A = fibroblasts at low passage (p6; 5% staining), B = fibroblasts at high passage (p20; 58% staining), C = endothelial cells at low passage (p6; 7% staining) and D = endothelial cells at high passage (p13; 68% staining).

3.5. Cellular senescence is associated with changes to the ratio of alternatively expressed isoforms for key ageing genes

For the genes selected to assess downstream consequences of age-related changes to splicing factor gene expression, we were able to detect expression for 3 genes (CDKN2A, VCAN and VEGFA) in fibroblasts and 5 genes (CDKN2A, VCAN1, GRP18, EFNA1 and VEGFA) in endothelial cells, although different genes were expressed in each cell type. We identified age-related differences in the ratio of alternatively expressed isoforms in fibroblasts for the CDKN2A (z = −3.811, p < 0.001) and VCAN (z = 4.157, p < 0.001) genes, with isoform changes of VEGFA isoforms also trending towards significance (Table 4). The ratio changes for CDKN2A in aged fibroblasts were driven by an increase in expression of transcripts coding for the p16INK4a isoform, whereas changes for VCAN were driven by an increase in the expression regulation of the variant 4 isoform. In endothelial cells, we noted changes in the mRNA isoform ratios of a different set of transcripts; the largest ratio changes were apparent for the VEGFA gene (z = −3.70, p < 0.001) (Table 4), whereas changes in CDKN2A isoform expression between “young” and “old” endothelial cells were less apparent (Table 4). The ratio changes for VEGFA in endothelial cells do not rely on changes to one mRNA transcript, but both of those measured were down-regulated with age.

Table 4. gene expression of alternatively expressed isoform ratios of age-related genes.

Gene expression measurements were taken for genes known to be associated with ageing in primary human fibroblasts and primary endothelial cells. Their association with cellular age is calculated by Mann–Whitney U statistical analysis between expression in old and young passage cells (p7 and p13 in endothelial cells; p7 and p18 in fibroblasts).

| GENE | PROBE ID | Isoform(s) | Fibroblasts | Endothelial cells

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| z | Prob > z | z | Prob > z | Differences in isoforms | Size of exon (bp) | |||

| CDKN2A | Hs00923894_m1 | NM_000077.4 | −4.099 | <0.0001 | −1.097 | 0.2727 | exon 1 – 456 | |

| NM_058195.3 | Alternative exon 1 | exon 1 – 353 | ||||||

| NM_058197.4 | Alternative exon 1 | exon 1 – 424 | ||||||

| Hs99999189_m1 | NM_058195.3 | 1.559 | 0.119 | 0.289 | 0.7728 | Alternative exon 1 | exon 1 – 353 | |

| Ratio | −3.811 | 0.0001 | −1.848 | 0.0647 | ||||

| VCAN | hs01007937_m1 | NM_001164097.1 | −3.984 | 0.0001 | NA | NA | exon 7 – 5261 | |

| hs01007943_m1 | NM_001164098.1 | −4.157 | <0.0001 | NA | NA | Alternative exon 7 | exon 7 – 2960 | |

| Ratio | 4.157 | <0.0001 | NA | NA | ||||

| EFNA1 | hs00358887_m1 | NM_004428.2 | NA | NA | 4.157 | <0.0001 | exon 3 inclusion | exon 3 – 65 |

| hs01020895_m1 | NM_182685.1 | NA | NA | 3.926 | 0.0001 | |||

| Ratio | NA | NA | −1.443 | 0.1489 | ||||

| VEGFA | Hs00903129 | NM_003376.5 | 4.157 | <0.0001 | 3.703 | 0.0002 | exon 6 included | exon 6 –71 |

| NM_001171624.1 | ||||||||

| Hs00900057 | NM_001171629.1 | 3.098 | 0.0019 | 3.34 | 0.0008 | Alternative exon 6 excluded | ||

| NM_001171627.1 | Alternative exon 6 excluded | |||||||

| NM_001171626.1 | Alternative exon 6 excluded | |||||||

| NM_001033756.2 | Alternative exon 6 excluded | |||||||

| NM_001025369.2 | Alternative exon 6 excluded | |||||||

| NM_001025368.2 | Alternative exon 6 excluded | |||||||

| Ratio | −1.903 | 0.057 | −3.703 | 0.0002 | ||||

3.6. ATM may be a regulator of splicing factor expression in man

In the InCHIANTI human microarray data we identified 19 transcripts which were associated with age and also with the expression of two of the most age-deregulated splicing factors SRSF6 and hnRNPA0 (supplementary Table 1). Of these, only 3 transcripts; Ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM), SAFB-like (SLTM) and poly (A) binding protein interacting protein 2 (PAIP2) have any reported role in RNA biology (Tsai et al., 2012; Berlanga et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2011). The transcript coding for ATM was considered of particular interest because of its role in the regulation of KH-type splicing (Zhang et al., 2011), its important role as part of the DNA damage response and its known activation in cell senescence (Suzuki et al., 2012). ATM expression in leukocytes was negatively correlated with advancing age in the InCHIANTI human data (coefficient −0.01402, FDR adjusted q-value = 1.9 × 10−5). Conversely ATM expression in the older fibroblast cells in vitro was increased with age (z = −3.046, p = 0.002).

3.7. siRNA-mediated transcript knockdown of the ATM gene influences the expression of several splicing factors in primary fibroblasts

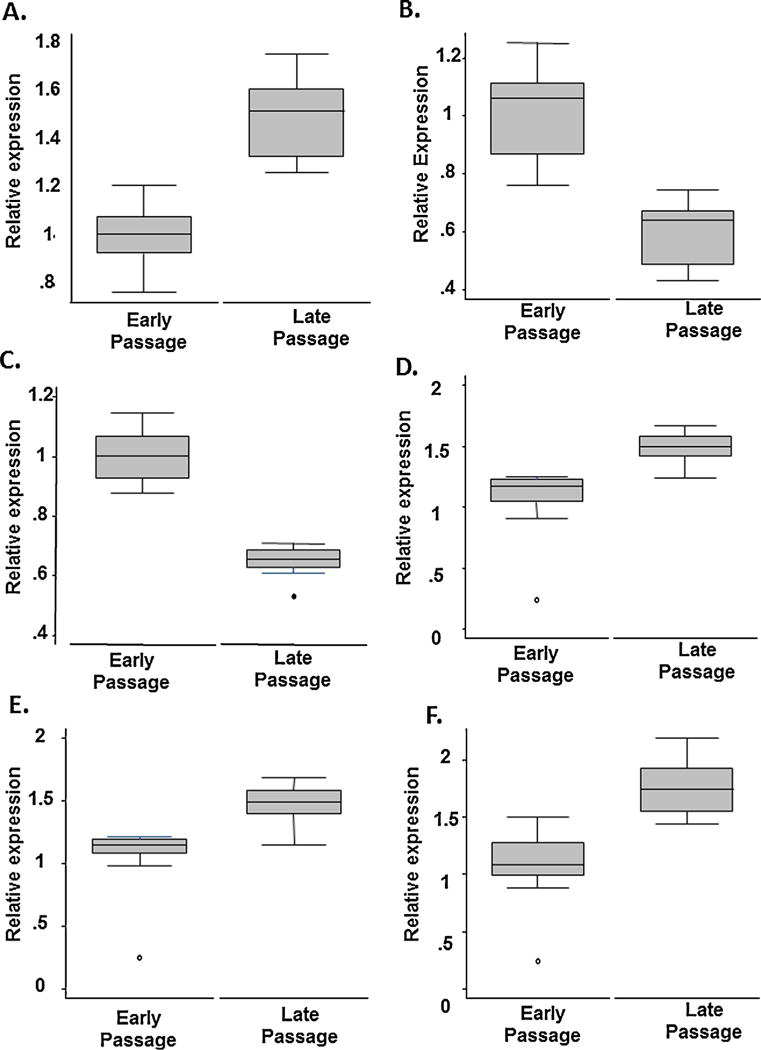

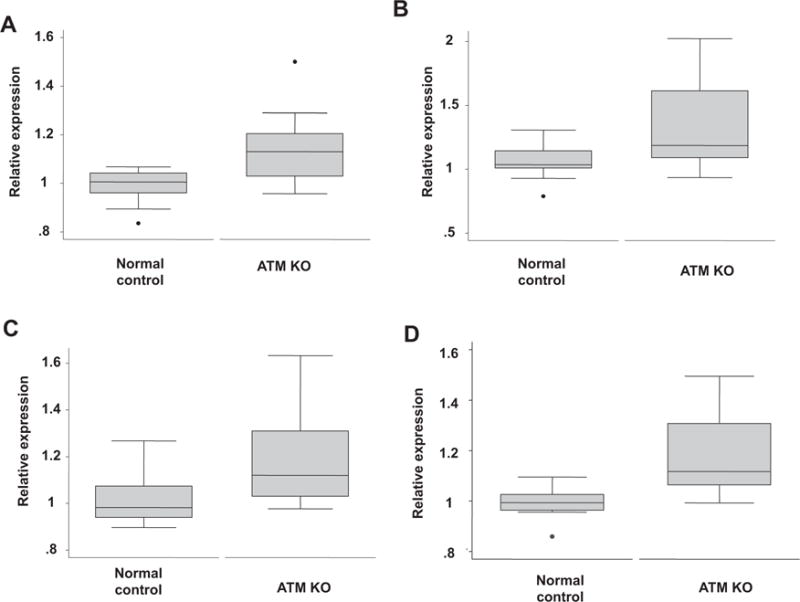

We undertook siRNA knock-down experiments of ATM expression in normal human dermal fibroblasts at passage nine. The positive control, an siRNA targeted against GAPDH produced an average of 75% reduction in GAPDH transcripts across 3 replicates. We achieved an average of 60% reduction in ATM expression in six biological replicates treated with an siRNA, in comparison to both untreated cells, and those treated with a scrambled siRNA (supplementary Table 2). RNA was extracted from the ATM siRNA-treated cells and the controls, and analysed for the expression levels of splicing factors by TLDA as described above. The expression of eight splicing regulatory factors were significantly increased in the cells exposed to the ATM siRNAs; SRSF3 (z = −.3.49, z = <0.001), HNRNPD (z = −2.252, p = 0.0243) HNRNPA1 (z = −2.483, p = 0.013), LSM14A (z = −2.078, p = 0.0377), SRSF1 (z = −2.598, p = 0.0094), SRSF2 (z = −2.021, p = 0.0433), SRSF7 (z = −2.252, p = 0.0243), and TRA2B (z = −2.483, p = 0.013) (Table 5). Representative graphs of the 4 transcripts showing the largest increases in expression following ATM siRNA treatment are shown in Fig. 4.

Table 5. Expression of core splicing and splicing regulator transcripts in siRNA-mediated transcript knockdown of the ATM gene.

Gene expression measurements for twenty transcripts in siRNA-mediated transcript knockdown of the ATM gene. Gene expression is relative to endogenous controls and relative to normal controls. Mann–Whitney U analysis was used to assess gene expression.

| Gene | z-value | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| AKAP17A | −1.039 | 0.2987 |

| HNRNPA0 | −1.212 | 0.2253 |

| HNRNPA2B1 | −0.981 | 0.3263 |

| HNRNPD | −2.252 | 0.0243 |

| HNRNPH3 | −0.866 | 0.3865 |

| HNRNPK | −1.617 | 0.106 |

| HNRNPM | −1.386 | 0.1659 |

| HNRNPUL2 | 0.058 | 0.954 |

| HNRNPA1 | −2.483 | 0.013 |

| LSM14A | −2.078 | 0.0377 |

| LSM2 | −1.617 | 0.106 |

| PNISR | −0.981 | 0.3263 |

| SF3B1 | −1.097 | 0.2727 |

| SRSF1 | −2.598 | 0.0094 |

| SRSF2 | −2.021 | 0.0433 |

| SRSF3 | −3.349 | <0.001 |

| SRSF6 | −0.404 | 0.6861 |

| SRSF7 | −2.252 | 0.0243 |

| TRA2B | −2.483 | 0.013 |

| IMP3 | −0.693 | 0.4884 |

Fig. 4.

Box plots of the top 3 splicing factor gene expressions changes obtained by TaqMan low-density array (TLDA) in normal Human Dermal Fibroblasts (A–C) and Human Aortic Endothelial Cells (D–F). Gene expression levels are given relative to endogenous controls in young and old fibroblasts (passage 7 and passage 18 respectively, and in young and old endothelial cells (passage 7 and passage 13 respectively). On the Y-axis are gene expression levels relative to endogenous controls by cell passage (X-axis). Changes in the expression of PNISR (A), HNRNPA1 (B), HNRNPA2B1 (C), HNRNPUL2 (D), HNRNPK (E) and HNRNPM (F) transcripts with increasing passage are given.

4. Discussion

In this study, we present the first evidence from human populations and from primary human cells ageing to senescence in vitro, that age-related deregulation of splicing patterns may be attributable to changes in the pool of core and regulatory splicing factors. Changes in splicing factor expression with age may thus be partially attributable to age-related changes in the expression of the Ataxia Telangiectasia Mutated (ATM) gene, which we have identified as a potential regulator of splicing factor expression for the first time. Changes to the normal splicing patterns are likely to have deleterious consequences for cell physiology, and may underlie some of the reductions in cellular adaptability and plasticity that occur during the ageing process (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

The top 4 splicing factor gene expression changes obtained by TaqMan low-density array (TLDA) in normal Human Dermal Fibroblasts treated with ATM siRNA. A = SRSF1, B = HNRNPA1, C = TRA2B and D = SRSF3 are given in this figure. Gene expression levels are given relative to endogenous controls in control fibroblasts at passage 9. These results represent the top 4 splicing factors (SRSF1, HNRNPA1, TRA2B and SRSF3) demonstrating increased expression in response to targeted knockdown of the ATM gene.

We found age-related differences in the milieu of splicing factors to be evident in expression array data from two separate human populations (InCHIANTI in whole blood white cell samples and SAFHS in isolated lymphocytes), and also in two primary cell lines of different lineages; fibroblasts and endothelial cells. It is of course not possible to infer activity of splicing factors from expression data alone, but our observation that the ratio of alternatively expressed transcripts also differ with age in blood, fibroblasts and endothelial cells indicates that the changes in splicing factor expression we note may have functional effect. The precise identity of splicing factors affected, and the direction of effect is not always consistent between different tissue types, indicating some degree of tissue specificity. This may also explain our observation that splicing factors associated with human ageing are more likely to be splicing regulators rather than core components in the spliceosome in whole blood (inCHIANTI dataset) than they are in isolated lymphocytes (SAFHS dataset). This may reflect differences in array coverage or it may reflect alterations in blood cell subtypes that are known to occur with age (Alam et al., 2012). Differences in the milieu of splicing factors between tissues is expected, since splicing patterns are known to be highly tissue specific, and the correct expression and regulation of specific genes is of paramount importance in controlling cellular identity. In primary fibroblasts, whole blood and leukocytes, most of the splicing factors we assessed demonstrated reduced expression with age, whereas in primary endothelial cells, both increases and decreases in splicing factor expression were noted. This is concordant with the differences in senescence processes previously reported between fibroblasts and endothelial cells (Shelton et al., 1999). One interesting feature between the datasets is the reduced expression of splicing activator transcripts (SRSF transcripts) in the fibroblasts and leukocytes and the increased expression of inhibitory splicing factors (hnRNP transcripts) in the endothelial cells, all of which are consistent with a decrease in splicing complexity. The alterations to the pool of SRSFs and hnRNPS we note could result in a decrease in the ability of senescent cells to regulate the inclusion of cassette exons. This is important since the inclusion of cassette exons containing premature termination codons (“poison” exons) is an emerging mechanism of controlling gene expression; transcripts containing such exons are susceptible to degradation by the nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) pathway (Grellscheid et al., 2011). These changes therefore could contribute to the loss of adaptability and plasticity of cells and tissues with age and have further consequences such as the altered proportions and effectiveness of innate and adaptive immune cells associated with an impaired response of the immune system to vaccines in the elderly and an enhanced vulnerability to infections (Weinberger et al., 2008).

A search for transcripts linked not only to age, but also to levels of some of the most deregulated splicing factors (SRSF6 and hnRNPA0) revealed the ATM gene as a potential regulator of splicing factor gene expression (see supplementary Table 2). ATM is a key regulator of the complex DNA damage response signalling pathway (Shiloh, 2006), where it binds directly to the site of double stranded DNA breaks and induces the activation of various cell cycle pathways including activation of MYC, ARF, MDM2 and p53 proteins in response to DNA damage (Campaner and Amati, 2012). DNA damage, caused by various intra- and extracellular insults, accumulates with age and has been identified as a major player in the ageing process alongside decreases in DNA repair capacity (Jackson and Bartek, 2009). Interestingly, we note that ATM levels are inversely correlated with age in leukocytes in population study, but positively correlated with age in the senescent fibroblasts. A decrease in levels of ATM transcripts with age is at first counterintuitive, but can be explained by the observation from publicly available microarray data that very high levels of ATM have been found in CD4 and somewhat lower levels in CD8+ve naïve T-cells (from a small sample of individuals, http://biogps.org/#goto=genereport&id=472), the proportions of which are known to decrease with age (Saule et al., 2006). Only by reference to a single population of cells from a single origin were we able to identify that levels of ATM transcripts actually increase, not decrease with age, as might be expected from a marker of accumulated DNA damage.

Our hypothesis that splicing factor expression may be attenuated during the ageing process in man by the expression of a potential regulator ATM is supported by our observation that targeted reduction of ATM transcript levels by siRNA in young (passage 9) fibroblasts results in the up-regulation of a subset of splicing factors. We elected to use young fibroblasts rather than senescent fibroblasts for several reasons. Firstly, senescent fibroblasts may have higher levels of other cellular stress proteins that may influence splicing factor expression, making it difficult to assess the effect of ATM knockdown alone. Senescent cells may also have accumulated mutations to the sequence elements required for regulation of expression. Finally, transfection of senescent fibroblasts is technically difficult, and may produce differences in gene expression profiles unrelated to the manipulation of ATM expression. Splicing factors demonstrating expression differences in response to targeted reduction of ATM expression include five of the 8 members of the SRSF family of splicing activators tested (SRSF1, SRSF2, SRSF3, SRSF7 and TRA2B; see Table 5), which are known to be master regulators of alternative splicing (Ghosh and Adams, 2011). In contrast, only 2/8 of the hnRNP splicing inhibitory transcripts tested (hnRNPA1 and hnRNPD) responded to ATM down-regulation by siRNA, indicating that some of the splicing inhibitors may be responsive to other factors. However, regulation of splicing factor expression is complex and has previously been shown to be influenced by other factors such as the expression of the MYC gene (Das et al., 2012), which is known to be another part of the DNA damage response (Campaner and Amati, 2012). Our data indicate that ATM is a negative regulator of members of the SRSF group of splicing factors, which together with other splicing factors such as the hnRNPs play a role in the orchestration of alternative splicing. One potential explanation for this is the role of ATM in the biogenesis of microRNAs, which are mainly repressors of gene expression by mRNA degradation or translational inhibition (Zhang et al., 2011). The regulatory role of ATM in miRNA biogenesis is modulated by KH-type splicing regulatory protein (KSRP) (Zhang et al., 2011). Accordingly, it has subsequently been reported that SRSF1 is regulated by miR-505 and miR-28 in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (Verduci et al., 2010). These findings indicate that investigation of ATM, KSRP and microRNA regulation is potentially a fruitful future avenue of study. Other future areas for consideration involve the targeted knockdown of multiple splicing regulators to observe effects on isoform expression. Splice site choice is dependent on the presence of multiple splicing regulators (SRSF proteins and hnRNPs), and effects on isoform expression may thus be difficult to assess from knockdown of a single regulator.

The strengths of our study are the combined use of both molecular epidemiological studies in two separate populations and mechanistic approaches in in vitro models of human cell ageing, to address the likelihood of changes in splicing factor expression during the ageing process. This allows us to use a ‘real-life relevant’ scenario in the form of the population studies, and also a more controlled analysis in a single homogeneous cell type, which is not subject to the same confounding influences and mix of tissue types that the epidemiological studies are. The use of cell model systems also allows intervention to assess causality and direction of effect. A further strength of our study arises from the fact that the two populations studied differ not only in their cell subtypes but also in their sample collection, storage and their analyses. Despite these differences we have found that the splicing factor milieu is associated with advancing age in both cohorts, despite the differences in experimental approach. This lends confidence to our results. It is also unclear whether fully senescent cells occur in vivo (Boisen and Kristensen, 2010). However, evidence from the Sedivy group indicates that a proportion of senescent cells are present in the tissues of ageing primates (Jeyapalan et al., 2007; Herbig et al., 2006), indicating that the use of replicative senescence is a reasonable model of ageing in vivo.

5. Conclusions

We report here the first human evidence that the differences to alternative splicing patterns that occur during the ageing process (Harries et al., 2011; Cao et al., 2011; Yannarell et al., 1977) may arise from mRNA expression changes to the milieu of core and regulatory splicing factors, and that a proportion of these are in turn regulated by the DNA damage response protein ATM. These data may represent a key link between age-related DNA damage and the processes of alternative splicing which direct adaptability, plasticity and cell identity. Alterations in alternative splicing may underpin both some of the heterogeneity of ageing in man and potentially some of the associations with age related diseases, many of which are highly dependent on correct splicing (Padgett, 2012; Wiszomirska et al., 2011; Nelson and Keller, 2007). More work is now required to elucidate the mechanisms by which the composition of the splicing factor milieu is regulated and how this in turn may impact on human ageing.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr Jonathan Powell for constructive review of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the intramural program of the National Institute on Ageing and Internal Funds of the University of Exeter Medical School.

Abbreviations

- ATM

Ataxia Telangiectasia Mutated gene

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- SRSF

SR splicing factor

- hnRNP

Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins

- LMNA

Lamin A/C gene

- qRT-PCR

quantitative real-time PCR

- TLDA

TaqMan Low Density Array

- RT-PCR

Reverse Transcription PCR

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mad.2013.05.006.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- Alam I, Goldeck D, Larbi A, Pawelec G. Aging affects the proportions of T and B cells in a group of elderly men in a developing country-a pilot study from Pakistan. Age (Dordr) 2012 doi: 10.1007/s11357-012-9455-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asumda FZ, Chase PB. Age-related changes in rat bone-marrow mesenchymal stem cell plasticity. BMC Cell Biology. 2011;12:44. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-12-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlanga JJ, Baass A, Sonenberg N. Regulation of poly(A) binding protein function in translation: characterization of the Paip2 homolog, Paip2B. RNA. 2006;12:1556–1568. doi: 10.1261/rna.106506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boisen L, Kristensen P. Confronting cellular heterogeneity in studies of protein metabolism and homeostasis in aging research. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 2010;694:234–244. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-7002-2_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caceres JF, Kornblihtt AR. Alternative splicing: multiple control mechanisms and involvement in human disease. Trends in Genetics. 2002;18:186–193. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(01)02626-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campaner S, Amati B. Two sides of the Myc-induced DNA damage response: from tumor suppression to tumor maintenance. Cell Division. 2012;7:6. doi: 10.1186/1747-1028-7-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao K, Blair CD, Faddah DA, Kieckhaefer JE, Olive M, Erdos MR, Nabel EG, Collins FS. Progerin and telomere dysfunction collaborate to trigger cellular senescence in normal human fibroblasts. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2011;121:2833–2844. doi: 10.1172/JCI43578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartegni L, Chew SL, Krainer AR. Listening to silence and understanding nonsense: exonic mutations that affect splicing. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2002;3:285–298. doi: 10.1038/nrg775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S, Anczukow O, Akerman M, Krainer AR. Oncogenic splicing factor SRSF1 is a critical transcriptional target of MYC. Cell Reports. 2012;1:110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimri GP, Lee X, Basile G, Acosta M, Scott G, Roskelley C, Medrano EE, Linskens M, Rubelj I, Pereira-Smith O, et al. A biomarker that identifies senescent human cells in culture and in aging skin in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1995;92:9363–9367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dujardin G, Lafaille C, Petrillo E, Buggiano V, Gomez Acuna LI, Fiszbein A, Godoy Herz MA, Nieto Moreno N, Munoz MJ, Allo M, et al. Transcriptional elongation and alternative splicing. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2013;1829:134–140. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrucci L, Bandinelli S, Benvenuti E, Di Iorio A, Macchi C, Harris TB, Guralnik JM. Subsystems contributing to the decline in ability to walk: bridging the gap between epidemiology and geriatric practice in the InCHIANTI study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2000;48:1618–1625. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh G, Adams JA. Phosphorylation mechanism and structure of serinearginine protein kinases. FEBS Journal. 2011;278:587–597. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07992.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goring HHH, Curran JE, Johnson MP, Dyer TD, Charlesworth J, Cole SA, Jowett JBM, Abraham LJ, Rainwater DL, Comuzzie AG, et al. Discovery of expression QTLs using large-scale transcriptional profiling in human lymphocytes. Nature Genetics. 2007;39:1208–1216. doi: 10.1038/ng2119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graveley BR. Alternative splicing: increasing diversity in the proteomic world. Trends in Genetics. 2001;17:100–107. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)02176-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graziotto JJ, Cao K, Collins FS, Krainc D. Rapamycin activates autophagy in Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome: implications for normal aging and age-dependent neurodegenerative disorders. Autophagy. 2012;8:147–151. doi: 10.4161/auto.8.1.18331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grellscheid S, Dalgliesh C, Storbeck M, Best A, Liu Y, Jakubik M, Mende Y, Ehrmann I, Curk T, Rossbach K, et al. Identification of evolutionarily conserved exons as regulated targets for the splicing activator Tra2b in development. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002390. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harman D. The aging process: major risk factor for disease and death. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1991;88:5360–5363. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.12.5360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harries LW, Hernandez D, Henley W, Wood A, Holly AC, Bradley-Smith RM, Yaghootkar H, Dutta A, Murray A, Frayling TM, et al. Human aging is characterized by focused changes in gene expression and deregulation of alternative splicing. Aging Cell. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00726.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harries LW, Fellows AD, Pilling LC, Hernandez D, Singleton A, Bandinelli S, Guralnik J, Powell J, Ferrucci L, Melzer D. Advancing age is associated with gene expression changes resembling mTOR inhibition: evidence from two human populations. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development. 2012a;133:556–562. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harries LW, Pilling LC, Hernandez LDG, Bradley-Smith R, Henley W, Singleton AB, Guralnik JM, Bandinelli S, Ferrucci L, Melzer D. CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein-beta expression in vivo is associated with muscle strength. Aging Cell. 2012b;11:262–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00782.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbig U, Ferreira M, Condel L, Carey D, Sedivy JM. Cellular senescence in aging primates. Science. 2006;311:1257. doi: 10.1126/science.1122446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hocine S, Singer RH, Grunwald D. RNA processing and export. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2010;2:a000752. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson SP, Bartek J. The DNA-damage response in human biology and disease. Nature. 2009;461:1071–1078. doi: 10.1038/nature08467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeyapalan JC, Ferreira M, Sedivy JM, Herbig U. Accumulation of senescent cells in mitotic tissue of aging primates. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development. 2007;128:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2006.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kervestin S, Jacobson A. NMD: a multifaceted response to premature translational termination. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2012;13:700–712. doi: 10.1038/nrm3454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurthy J, Ramsey MR, Ligon KL, Torrice C, Koh A, Bonner-Weir S, Sharpless NE. p16INK4a induces an age-dependent decline in islet regenerative potential. Nature. 2006;443:453–457. doi: 10.1038/nature05092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulminski A, Culminskaya I. Genomics of human health and aging. Age. 2013:1–15. doi: 10.1007/s11357-011-9362-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meshorer E, Soreq H. Pre-mRNA splicing modulations in senescence. Aging Cell. 2002;1:10–16. doi: 10.1046/j.1474-9728.2002.00005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell B, Kammerer C, Reinhart L, Stern M. NIDDM in Mexican-American families, Heterogeneity by age of onset. Diabetes Care. 1994;17:567–573. doi: 10.2337/diacare.17.6.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson PT, Keller JN. RNA in brain disease: no longer just “the messenger in the middle”. Journal of Neuropathology & Experimental Neurology. 2007;66:461–468. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000240474.27791.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padgett RA. New connections between splicing and human disease. Trends in Genetics. 2012;28:147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Q, Shai O, Lee LJ, Frey BJ, Blencowe BJ. Deep surveying of alternative splicing complexity in the human transcriptome by high-throughput sequencing. Nature Genetics. 2008;40:1413–1415. doi: 10.1038/ng.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Research. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilling LC, Harries LW, Powell J, Llewellyn DJ, Ferrucci L, Melzer D. Genomics and successful aging: grounds for renewed optimism? The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2012;67A:511–519. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan NA, Zwetsloot KA, Westerkamp LM, Hickner RC, Pofahl WE, Gavin TP. Lower skeletal muscle capillarization and VEGF expression in aged vs. young men. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2006;100:178–185. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00827.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saule P, Trauet J, Dutriez V, Lekeux V, Dessaint JP, Labalette M. Accumulation of memory T cells from childhood to old age: central and effector memory cells in CD4+ versus effector memory and terminally differentiated memory cells in CD8+ compartment. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development. 2006;127:274–281. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton DN, Chang E, Whittier PS, Choi D, Funk WD. Microarray analysis of replicative senescence. Current Biology. 1999;9:939–945. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80420-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiloh Y. The ATM-mediated DNA-damage response: taking shape. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 2006;31:402–410. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CWJ, Valcárcel J. Alternative pre-mRNA splicing: the logic of combinatorial control. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 2000;25:381–388. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01604-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strimmer K. A unified approach to false discovery rate estimation. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:303. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M, Suzuki K, Kodama S, Yamashita S, Watanabe M. Persistent amplification of DNA damage signal involved in replicative senescence of normal human diploid fibroblasts. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2012;2012:310534. doi: 10.1155/2012/310534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomas-Loba A, Flores I, Fernandez-Marcos PJ, Cayuela ML, Maraver A, Tejera A, Borras C, Matheu A, Klatt P, Flores JM, et al. Telomerase reverse transcriptase delays aging in cancer-resistant mice. Cell. 2008;135:609–622. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai YC, Greco TM, Boonmee A, Miteva Y, Cristea IM. Functional proteomics establishes the interaction of SIRT7 with chromatin remodeling complexes and expands its role in regulation of RNA polymerase I transcription. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics. 2012;11:60–76. doi: 10.1074/mcp.A111.015156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verduci L, Simili M, Rizzo M, Mercatanti A, Evangelista M, Mariani L, Rainaldi G, Pitto L. MicroRNA (miRNA)-mediated interaction between leukemia/lymphoma-related factor (LRF) and alternative splicing factor/splicing factor 2 (ASF/SF2) affects mouse embryonic fibroblast senescence and apoptosis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010;285:39551–39563. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.114736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Geiger H, Rudolph KL. Immunoaging induced by hematopoietic stem cell aging. Current Opinion in Immunology. 2011;23:532–536. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger B, Herndler-Brandstetter D, Schwanninger A, Weiskopf D, Grubeck-Loebenstein B. Biology of immune responses to vaccines in elderly persons. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2008;46:1078–1084. doi: 10.1086/529197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiszomirska H, Piekielko-Witkowska A, Nauman A. Disturbances of alternative splicing in cancer. Postepy Biochemii. 2011;57:257–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yannarell A, Schumm DE, Webb TE. Age-dependence of nuclear RNA processing. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development. 1977;6:259–264. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(77)90026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Wan G, Berger FG, He X, Lu X. The ATM kinase induces microRNA biogenesis in the DNA damage response. Molecular Cell. 2011;41:371–383. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.