Abstract

Anosmia and hyposmia, the inability or decreased ability to smell, is estimated to afflict 3–20% of the population. Risk of olfactory dysfunction increases with old age and may also result from chronic sinonasal diseases, severe head trauma, and upper respiratory infections, or neurodegenerative diseases. These disorders impair the ability to sense warning odors in foods and the environment, as well as hinder the quality of life related to social interactions, eating, and feelings of well-being. This article reports and extends on a clinical update commencing at the 2016 Association for Chemoreception Sciences annual meeting. Included were reports from: a patient perspective on losing the sense of smell with information on Fifth Sense, a nonprofit advocacy organization for patients with olfactory disorders; an otolaryngologist’s review of clinical evaluation, diagnosis, and management/treatment of anosmia; and researchers’ review of recent advances in potential anosmia treatments from fundamental science, in animal, cellular, or genetic models. As limited evidence-based treatments exist for anosmia, dissemination of information on anosmia-related health risks is needed. This could include feasible and useful screening measures for olfactory dysfunction, appropriate clinical evaluation, and patient counseling to avoid harm as well as manage health and quality of life with anosmia.

Keywords: genetics, neural reorganization, olfactory dysfunction, quality of life, stem cell regeneration, treatment

Introduction

Few people consciously appreciate the range of information provided by the sense of smell, from detecting warning harmful odors from the environment to forming a major part of many of life’s pleasurable experiences, whether eating a meal, a walk in the countryside, or intimacy with one’s partner. Hence, inability to smell or losing the sense of smell—anosmia—can have a severe impact on health and quality of life. Recent nationally representative data reveals that anosmia afflicts 3.2% of US adults who are aged more than 40 years (3.4 million people) (Hoffman et al. 2016), and this number increases with age (14–22% of those 60 years and older; Kern et al. 2014; Pinto et al. 2014; Hoffman et al. 2016). These data have informed US public health recommendations for the need to appropriately evaluate and treat individuals with olfactory disorders thereby reducing the negative health effects of these disorders (Promotion USOoDPaH 2017). The growing attention to the problem of anosmia provided impetus for a clinical symposium at the 2016 Association for Chemoreception Sciences annual meeting (Bonita Springs, FL). The multidisciplinary Clinical Symposium brought together perspectives on anosmia from the patient, physician, and basic scientist—from the human to recent advances in fundamental science, in animal, cellular, or genetic models (Boesveldt et al. 2016).

This review article extends the update on anosmia presented at the symposium and provides an introduction to population estimates of olfactory dysfunction and the impact on individual health and well-being. Next is a review of current knowledge and status regarding diagnostics and prognosis in the ENT clinic. It also presents recent insights in neural reorganization processes in the brain that occur with olfactory loss and discusses exciting developments in fundamental research with the aim of treating certain anosmias (e.g., understanding the genetics behind specific forms of olfactory loss, gene therapeutic approaches to restore olfactory loss, and olfactory epithelial stem cell regeneration). The article ends with recommendations for screening and testing for olfactory dysfunction, recommendations for managing the health risks of olfactory loss, and calls for continued research into possible treatments.

Prevalence of olfactory dysfunction in the general population

Olfactory functioning can be categorized as a range of normal (normosmic) to diminished (hyposmic) and absent (anosmic) ability to detect and correctly label odors. Anosmia can be specific (Croy et al. 2015), arising from a genetic variation, such as the inability to detect the musky smell of androstenone (Bremner et al. 2003), which is explained by polymorphisms in the OR7D4 gene (Knaapila et al. 2012). Altered olfactory perception or dysosmia also exists. Dysosmia can be the distortion of perceived odor quality (parosmia, e.g., smelling burnt paper instead of baby powder) or a phantom olfactory sensation with no apparent olfactory stimulus (olfactory hallucinations, phantosmia). The focus of the present article however is on anosmia or inability to smell/loss of smell of all odors, except for trigeminal sensations.

As olfactory testing is not part of general health exams, clinicians need to rely on patient self-report of the problem. Of importance is that self-report measures are sensitive (correct recognition of olfactory dysfunction) and specific (correct recognition of normal) in comparison with a gold standard. The general consensus is that self-report of the sense of smell is specific but not sensitive—people do not recognize the problem (Wehling et al. 2011; Schöpf and Kollndorfer 2015; Adams et al. 2016). In a nationally representative sample of older US adults (NSHAP), 12.4% reported their sense of smell as fair or poor (using a 5-point Likert scale), whereas 22.0% had objective olfactory dysfunction. Among those with measured olfactory dysfunction, 74.2% did not recognize it (Adams et al. 2016). However, recent studies suggest that we can improve the sensitivity of self-report through multiple questions (Rawal et al. 2015, 2016). Expanding the queries beyond “do you have a problem now” to include notice of a change in ability since a younger age, and the presence of phantom sensations have netted improved sensitivity. In the NHANES olfactory protocol, an index of self-report (current ability, loss, and phantosmia) showed a specificity of 78% and sensitivity of 54% compared with individuals who were tested for anosmia on an eight-odor identification task (Hoffman et al. 2016). This reported sensitivity is very close to that reported in a large clinical sample (n = 1555) seeking evaluation at a taste and smell center (Seok et al. 2017). The prevalence of olfactory impairment by self-report in NHANES among adults was 25.1% versus 12.4% measured impairment. However, a single measure of olfactory function by identification neither captures perceived changes with age nor a decrease in perceived intensity of odors that are still correctly identified but less vibrant than once experienced. Thus, the NHANES self-reported olfactory function index appears to offer a reasonable way to screen for anosmia in the community (see Figure 1 for the questions) and setup for further examination to objectify the complaints.

Figure 1.

A multi-step guideline for community screening of olfactory (dys)function.

In clinical practice (see also section Anosmia in the ENT clinic—examination, diagnosis, and prognosis), anosmia is usually defined by an odor identification task alone or in combination with an odor threshold or discrimination task. For the odor identification, the patient sniffs an odor embedded within impregnated test strips (such as the UPSIT; Doty, Shaman, Kimmelman, et al. 1984), felt-tip pens (e.g., Sniffin Sticks; Hummel et al. 2007), or generated by an olfactometer. Correct odor identification requires enough sensory information to perceive and recognize the odor as familiar, retrieve the odor name from memory, and form the odor-word relationship. The patient is typically prompted with a list of the target odor and distractors as healthy participants presented with familiar everyday objects, such as coffee, peanut butter or chocolate, correctly name only around 50% of odors in free recall tasks (Cain 1979). Most commercially available odor identification tasks have the patient select the correct response from three distractors. The identification task needs to minimize cognitive and cultural influences on performance. Cognitive challenges of odor identification tasks can be attenuated by providing picture of the odors (Murphy et al. 2002). Providing odors that are appropriate and familiar to an age cohort or ethnic group can minimize cultural influences on odor misidentification. A drawback of testing odor identification is that the odors presented are suprathreshold, and the task is thus less sensitive to subtle changes in odor sensitivity. Odor threshold testing on the other hand is designed to measure (changes in) olfactory sensitivity; however, for a reliable result, this typically requires a lengthier examination (15–20 min) and will still only yield the outcome for one particular odor. Combining these different measures (subjective and objective testing) will provide insight in the severity and type of olfactory dysfunction.

Quality of life

Impairment of olfactory function is known to affect the quality of life of patients (Temmel et al. 2002; Frasnelli and Hummel 2005; Keller and Malaspina 2013; Croy et al. 2014; Kollndorfer et al. 2017). Individuals with olfactory dysfunction report difficulties with cooking, decreased appetite and enjoyment of eating, challenges with maintaining personal hygiene and social relationships, fear of hazardous events or feeling less safe (Temmel et al. 2002), and greater depressive symptoms and loneliness (Gopinath et al. 2011; Sivam et al. 2016). Women appear more likely to report depression and anxiety related to the olfactory impairment than do men (Philpott and Boak 2014). Patients who experience distorted odor quality, such as parosmia, may have greater disruption to their daily life than patients who suffer from hyposmia or anosmia (Frasnelli and Hummel 2005).

The sense of smell is important to detect warning of many hazards that are encountered in daily life, such as smoke, gas, and spoiled food (Temmel et al. 2002; Reiter and Constanzo 2003; Santos et al. 2004; Croy et al. 2014). The NHANES data revealed that, among adults 70 years and older, 20% were unable to identify the warning odor smoke and 31% natural gas (Hoffman et al. 2016), which is a major public health concern (Reiter and Constanzo 2003; Hummel and Nordin 2005; Pence et al. 2014). In a survey among members of the Dutch anosmia association, 44% of the patients indicated that they fear exposure to some of these dangers due to their disorder (Boesveldt et al. 2015). Patients with anosmia were three times more likely to be at risk of experiencing a hazardous event than normosmics (Pence et al. 2014), and between 25% and 50% of anosmics reported accidentally eating rotten or spoiled food (Stevenson 2010).

The sense of smell plays a major role in eating behavior, for both anticipation and stimulation of appetite (Boesveldt and De Graaf 2017) and for flavor perception during consumption of food (Hummel and Nordin 2005; Stevenson 2010; Croy et al. 2014). Fifth Sense, the United Kingdom-based charity for people affected by smell and taste disorders, surveyed its members on the impact of their condition on their quality of life. From 496 respondents, 92% reported a reduced appreciation of food and drink, whereas 55% reported going out to restaurants less frequently (Philpott and Boak 2014). Among 125 members of the Dutch Anosmia Association, 43.2% reported less of an appetite (Boesveldt et al. 2015), though this may not necessarily lead to changes in healthy eating patterns, food intake, or nutritional status (Toussaint et al. 2015). Food may take on different meaning to those with olfactory losses. Afflicted individuals may change their food preferences, trying to use nonolfactory sensations to maintain food enjoyment (Duffy et al. 1995; Kremer et al. 2007, 2014), which may result in weight gain (Aschenbrenner et al. 2008), particularly among women (Ferris and Duffy 1989). Conversely, patients with olfactory impairment may lose interest in food (Temmel et al. 2002; Stevenson 2010), preferring healthy food choices (Aschenbrenner et al. 2008), or in the negative, lose weight, particularly among men (Ferris and Duffy 1989).

Because individuals may respond differently to the olfactory impairment, it is important for health professionals, particularly registered dietitians, to assess the impact of perceived and/or measured impairment on the patient’s eating behaviors and nutritional status. Screening questions could ask the patient of changes since the problem started, including have his/her eating habits changed in response to the change in the way food “tastes”; avoiding any foods; have the types of foods they eat changed; adding anything to your foods to make the “taste” of the food any better; taking dietary supplements or using any complimentary or functional medicine therapies (Duffy and Hayes 2014); altered food preferences (e.g., see de Bruijn et al. 2017); or a simple screening tool to assess adherence to dietary guidelines (e.g., van Lee et al. 2012). More research on this topic is needed to gain insight into the effect of changes in olfactory perception on dietary behavior of anosmic patients and to which extent these changes affect their health and nutritional status. This knowledge could be used to advise anosmic patients on how to cope with the loss of their sense of smell with respect to their daily food intake.

The loss of the ability to smell (unpleasant) odors can greatly impact personal hygiene (Hummel and Nordin 2005; Croy et al. 2014). Patients can exaggerate their personal hygiene, for example, by showering several times a day or excessive use of perfume or aftershave (Temmel et al. 2002). Patients also report that their olfactory impairment affects their relationship with their partner, friends, and family (Blomqvist et al. 2004; Philpott and Boak 2014). Women may be more negatively affected than men, and younger patients more affected than elderly patients (Temmel et al. 2002; Philpott and Boak 2014; Boesveldt et al. 2017).

Overall, impairment of olfactory function can challenge feelings of health and well-being. As the level of impact depends on the character and severity of the impairment and the individual’s response, individuals with measured and/or self-reported olfactory impairment should be evaluated for changes in diet and health behaviors and status. The US Healthy Goals 2020 aspires to “reduce the proportion of adults with chemosensory (smell or taste) disorders who as a result have experienced a negative impact on their general health status, work, or quality of life in the past 12 months.”

Health care for patients with smell and taste disorders

Besides several specialized centers in the United States, the Smell and Taste clinic in Dresden (Germany), several smell and taste clinics have been founded in Europe during the past years. The United Kingdom’s first Smell and Taste Clinic was opened in 2010 and the first Dutch Smell and Taste center started in 2015.

Patients with chemosensory disorders report difficulty finding and receiving the appropriate level of care. Landis et al. found that, among 230 patients visiting a smell and taste clinic, 80% of the patients visited on average 2.1 ± 0.1 other physicians before visiting this clinic. Moreover, 60% of patients received unclear, unsatisfactory, or no information at all about their disorder and its consequences (Landis et al. 2009). This lack of sufficient information might be one reason why patients can have several consultations with other clinicians before visiting a specialized smell and taste clinic. The US Healthy Goals 2020 aims to “Increase the proportion of adults with chemosensory (smell or taste) disorders who have seen a health care provider about their disorder in the past 12 months.”

Part of the challenge of finding appropriate care is that patients have difficulties in identifying and distinguishing their smell and taste disorder (Frasnelli and Hummel 2005; Wehling et al. 2011; Croy et al. 2014; Pence et al. 2014; Adams et al. 2016). For example, 67% of the members of the Dutch anosmia association self-identify their disorder as a smell and taste disorder (Boesveldt et al. 2015), whereas objective testing in a group of 4680 patients visiting the Smell and Taste Clinic at the Dresden University Hospital found only 6.5% of the patients met the criteria for smell as well as taste loss (Fark et al. 2013). Temmel et al. found in their study 11 patients, who self-reported normal olfactory functioning, to be anosmic (n = 5) or hyposmic (n = 6) after testing their sense of smell (Temmel et al. 2002). These two examples demonstrate the importance of objective smell and taste tests in addition to the self-reported complaints of the patient. Of the members of the Dutch anosmia association, only 24.8% were subjected to a smell and/or taste test, whereas 60.8% received a clinical diagnosis (Boesveldt et al. 2015).

Diagnosis of the olfactory disorder is important in the prognosis for the patient. Among the patients in the study by Landis et al. (2009), 30% did not receive any information about their prognosis before visiting a smell and taste clinic. Welge-Luessen also stresses the importance of a clear diagnosis, as this plays a role in acceptance of the disorder and the learning of coping strategies (Welge-Luessen and Hummel 2013).

Anosmia in the ENT clinic—examination, diagnosis, and prognosis

Anosmia can result from many underlying diseases. The most common causes are sinonasal diseases, postinfectious disorder, and post-traumatic disorder (Damm et al. 2004; Nordin and Brämerson 2008). Other etiologies (e.g., congenital, idiopathic, toxic disorders, or disorders caused by a neurodegenerative disease) are less common but nonetheless important to rule out. In a patient suffering from an olfactory disorder, the first stage of the diagnosis is the patient’s medical history. The clinician should evaluate how the disorder started, for example, suddenly, after a trauma or a (severe) cold, which then makes a post-traumatic disorder or a disorder after an upper respiratory tract infection (post-URTI), very likely. Conversely, if the patient has difficulties recalling the exact moment the disorder began and describes olfactory fluctuations, sinonasal disorders can be assumed. A gradual onset and difficulties in recalling a triggering event also might suggest age-related, idiopathic disorder, or disorder due to a neurodegenerative disease. In contrast to patients with sinonasal disorders, patients suffering from neurodegenerative diseases also describe the smell loss as either “gradually diminishing” or as “gone” but rarely as fluctuating. Moreover, the patient has to be asked whether he/she remembers any olfactory function at all to rule out a congenital disorder. Intake of medications has to be evaluated as well as preceding operations or toxic exposures, for example, in a work environment. A thorough ENT examination (for guidelines, see Figure 2) for olfactory disorders should include nasal endoscopy to visualize the olfactory cleft and to rule out any visual endonasal pathology. Special care is taken to notice septal deviation, tumors, and signs of acute or chronic sinonasal disease such as secretion, crusts, and polyps (Welge-Luessen et al. 2014). Testing of olfactory function using a validated and standardized test is mandatory because subjective ratings of olfactory function are not always reliable (as described above; Wehling et al. 2011; Adams et al. 2016). Depending on cultural background, olfactory testing is usually performed using, for example, the UPSIT (Doty, Shaman, Applebaum, et al. 1984) or the Sniffin Sticks test battery (Hummel et al. 1997) or any other validated test. Recording of olfactory-evoked potentials is possible but usually not performed routinely even though it is often applied in medico-legal cases (Hummel and Welge-Luessen 2006). The endonasal findings in postinfectious disorders, in disorders related to age, to neurodegenerative diseases or to trauma are usually without any pathology. If needed, additional imaging (computer tomography or magnetic resonance imaging) can be performed. The volume of the olfactory bulb (OB) can be used to predict prognosis of the olfactory dysfunction (Rombaux et al. 2012). Therapies for olfactory dysfunction should match the etiology of the disorder.

Figure 2.

Guidelines for clinical evaluation and outcomes (based on Malaty and Malaty 2013).

In sinonasal disorders, therapy consists of steroids, either topical or systemic. Topical steroids so far have only been proven to be effective in allergic rhinitis (Stuck et al. 2003), especially if applied in combination with an antihistamine such as azelastinhydrochloride as provided in the trademarked AzeFlu spray (Klimek et al. 2017). However, if drops are used, the correct application of drops to reach the olfactory cleft is crucial and has to be instructed: in a head-down forward position (Benninger et al. 2004; Scheibe et al. 2008, but see also Mori et al. 2016). In sinonasal disorders, peroral steroids have been proven to be effective (Jafek et al. 1987; Banglawala et al. 2014), even though both duration and dose of the applied steroids shows great variation and remains controversial. Importantly, even though not often encountered by otorhinolaryngologists, side effects of steroids such as osteonecrosis have to be considered (Dilisio 2014). Surgical therapy in form of functional endoscopic sinus surgery might improve some cases of olfactory dysfunction. The rationale behind this is to improve ventilation and thus to decrease inflammation in the area of the olfactory cleft which is likely to contribute to the presence of the disorder (Yee et al. 2010). Nevertheless, because it is very difficult to predict if olfactory function will improve with the surgery, conservative treatment in cases of chronic rhinosinusitis with polyps is recommended (Rimmer et al. 2014). Several attempts have been undertaken to identify factors predicting surgical outcome and success rate in regard to olfactory function. To date, no histologic factors have been identified to predict postoperative outcome (Soler et al. 2010; Nguyen et al. 2015); previous sinus operations (Nguyen et al. 2015) and the existence of an aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease (Katotomichelakis et al. 2009) lower the chance of postoperative olfactory restoration.

In post-URTI disorders, spontaneous recovery is observed in 32–66% of patients (Philpott and DeVere 2014). Different therapeutic approaches have been reported to support the spontaneous regeneration. Smell training, first described by Hummel et al. (2009), seems to be the most effective one. Smell training sets consist of four different odorants that have to be sniffed intensely twice a day for several seconds each over a period of at least 4 months. Its effect has been confirmed in a large multicenter cross-over study (Damm et al. 2014) as well as by a recent meta-analyses (Pekala et al. 2016; Sorokowska et al. 2017), and it seems to be even more effective when a variety of odorants are rotated over time and training is prolonged (Altundag et al. 2015). Application of vitamin A nose drops might be of additional benefit but has to be proven yet, whereas peroral application of vitamin A did not improve olfactory function (Reden et al. 2012). Application of intranasal citrate might also be of benefit to these patients (Whitcroft et al. 2016).

Spontaneous recovery rates in post-traumatic olfactory disorders takes place in a much lower percentage of patients probably due to post-traumatic scarring in the area of the lamina cribrosa, accompanied by intracranial lesions (Lotsch et al. 2015) and shearing injuries. Attempts have been undertaken to improve olfactory outcome by applying steroids, either perorally (Jiang et al. 2010) or intraseptally (Fujii et al. 2002), which have been shown to improve olfactory function in animal models (Kobayashi and Costanzo 2009). However, both studies included only a small number of patients with large variation, no controls, and reported only limited effects. On the other hand, ZincGluconat, either alone or in combination with peroral steroids, improved olfactory function compared with spontaneous recovery or steroid treatment (Jiang et al. 2015). Smell training, as described above, can be offered in post-traumatic disorders and Parkinson’s disease with some potential improvement in olfactory function (Haehner et al. 2013; Konstantinidis et al. 2013).

Further studies with larger numbers of patients are needed to prove the clinical significance of treatments for individuals suffering from olfactory dysfunction related to sinonasal disease, upper respiratory tract infection, and post-trauma. No proven therapy exists for age-related smell loss or idiopathic smell loss.

Neural plasticity on olfactory loss and (re)gain

Olfactory loss not only entails vast social, emotional, and behavioral consequences as described above but also initiates reorganization processes in the brain. All our sensory systems are highly plastic, but although for the auditory and visual system these processes have been described in quite some detail, the understanding of neuronal processes occurring after loss of the olfactory sense is still largely unknown (see, e.g., Kollndorfer, Jakab, et al. 2015). The olfactory system is extraordinarily plastic due to mechanisms that are under extensive investigation (Mainland et al. 2002; Wilson et al. 2004). This plasticity, which can be observed at both the cellular and cognitive level, provides adaptive opportunities for optimizing sensory function in cases of learning and experience. In contrast to these gains in function, events such as trauma, injury, disease, and sensory deprivation can induce plasticity among sensory systems in a reductive manner. The neural system that processes olfactory-related information consists of many more components and regions than just the piriform and orbitofrontal cortices. Here, we focus on the structural and functional brain reorganization after olfactory loss caused by infections of the upper nasal tract, and not on deficits after traumatic brain injury as these damages might lead to neural changes themselves.

Patients with anosmia are by definition not able to perceive olfactory stimuli consciously. Therefore, the common way to investigate function by using stimulation is impossible, as no functional brain activation in response to pure odorants can be expected. Most investigations therefore employ stimulation of the trigeminal system (Frasnelli and Hummel 2007; Iannilli et al. 2007), which is closely connected and interacts with the olfactory system to create a uniform flavor experience (Lundström et al. 2011). Central processing of trigeminal stimuli after olfactory loss reflects the strong relationship between these sensory systems (for review, see Reichert and Schöpf 2017). Besides the effect on global functional connections of the brain due to smell loss (Kollndorfer et al. 2014), a regain of olfactory function associated with olfactory training can lead to re-established functional connections (Kollndorfer, Fischmeister, et al. 2015). The training, associated with improvements of olfactory threshold scores, led to an increase of functional connections in networks involved in chemosensory processing (Kollndorfer, Fischmeister, et al. 2015). Furthermore, before training, piriform cortex showed a multitude of connections to nonolfactory regions, which declined after training (Kollndorfer et al. 2014).

Most studies investigating morphological changes after olfactory loss have focused on a single region, the OB (for reviews, see Rombaux et al. 2009; Huart et al. 2013). A generalized claim on global structural reorganization processes is more challenging, as structural changes are understudied and existing literature reports on a decrease of volume in olfactory areas, as well as regions with more generalized functions (see, e.g., Bitter, Brüderle, et al. 2010; Bitter, Gudziol, et al. 2010; Peng et al. 2013; Yao et al. 2014). Findings of both investigational approaches could be a matter of causality, as decreased gray matter volume in certain areas and/or small OB volumes could also be a risk factor in developing anosmia in the first instance (see, e.g., Patterson et al. 2015).

Although it has been established that function and structure are affected by sensory loss, many questions on how this information could be used to establish a complete picture and if other mechanisms in the brain, such as metabolism are affected, remain to be answered. More longitudinal studies on the rehabilitation of the sense of smell, lost by various causes or even qualitative disorders such as parosmia, are needed. A more generalized view of neuronal processes from multimodal neuroimaging can detect subtle reorganization processes between brain structure and function in olfactory loss and regain. This generalized approach will help to illuminate the underlying mechanisms of olfactory loss and will foster the development of biomarkers to predict therapy success in the future.

Recent advances in understanding olfactory loss and opportunities for treatment

Genetics behind olfactory loss

Understanding the genes underlying a disease is of fundamental importance. The genetic basis of other inherited sensory defects such as congenital blindness and deafness is well investigated, and this knowledge has been instrumental in developing cell and gene therapies for these disorders, in which the faulty gene is replaced with a working one. Hereditary deafness has been linked to mutations in over 90 different genes and counting (van Camp and Smith 2016), and gene therapy strategies exploiting this knowledge have successfully treated hearing loss in mice (Askew et al. 2015). Congenital blindness is a particularly attractive target for gene therapy given the relative accessibility of the retina from the outside of the body. Mutations in more than 200 different genes have been linked to photoreceptor cell death in familial retinal degeneration, and gene therapy trials using viral gene delivery have been ongoing for almost a decade for a multitude of disorders characterized by hereditary blindness (Sahel et al. 2015).

The genetic basis of anosmia, in contrast, is poorly understood. Some progress has been made in identifying genes involved in syndromic cases of anosmia, such as Kallmann’s syndrome (Franco et al. 1991; Legouis et al. 1991; Dode et al. 2003, 2006; Falardeau et al. 2008; Hardelin and Dode 2008; Kim et al. 2008; Dode and Hardelin 2010; Miraoui et al. 2013; Moya-Plana et al. 2013), indifference to pain (Goldberg et al. 2007; Nilsen et al. 2009; Weiss et al. 2011), and CHARGE syndrome (Vuorela et al. 2008; Jongmans et al. 2009). In contrast, few studies in the literature have attempted to determine causal genes for isolated congenital anosmia (ICA), where anosmia is not associated with a broader syndrome. Feldmesser et al. (2007) failed to identify regions of the genome associated with inherited anosmia in two families, nor did they identify mutations in three components of the olfactory receptor signaling pathway in 61 unrelated individuals with anosmia. However, one study found mutations in CNGA2, a member of the olfactory signaling transduction pathway, in two brothers with ICA but not in 31 additional unrelated patients with ICA (Karstensen et al. 2015). Another study found that a rare X-linked mutation in the TENM1 gene was linked to anosmia and a mouse knockout model of Tenm1 was hyposmic (Alkelai et al. 2016). In summary, more than 100 altered genes have been discovered in patients born without hearing, and more than 200 genes are implicated in patients born without sight, but, apart from Kallmann-associated genes, so far researchers have identified only two genes associated with ICA.

The lack of studies examining the genetic basis of ICA in comparison with other hereditary sensory deficits highlights the necessity of further research into this disorder, particularly with new knowledge that the prevalence of olfactory disorders can match that of hearing and vision disorders (Hoffman et al. 2016). Identification of these genes will help with diagnosis, prognosis, and possible treatment of congenital anosmia. Indeed, the physiology that makes the retina such an attractive target for gene therapy applies equally well to the olfactory system, whose neurons are easily accessible in the nasal cavity.

Gene therapeutic approaches for ciliopathies

Ciliopathies represent a class of pleotropic congenital disorders of which olfactory loss is a clinical manifestation (Kulaga et al. 2004; Iannaccone et al. 2005; Tadenev et al. 2011; McIntyre et al. 2012, 2013). Given that all the machinery necessary for odor detection is localized to the cilia of olfactory sensory neurons, ciliopathies result in sensory deprivation. Mutations or deletions of genes encoding for proteins that build or maintain cilia often result in anosmia. Importantly, recent work from the Martens laboratory demonstrated for the first time the potential for gene therapy, using noninvasive intranasal delivery of viruses encoding replacement genes, to restore olfactory function in mouse models of ciliopathies (McIntyre et al. 2012, 2013). Specifically, gene replacement of the IFT88 protein by adenoviral delivery to the nasal cavity restored odor detection in anosmic animals with a hypomorphic mutation in the IFT88 gene. This work also showed for the first time that it is possible to regrow a cilium on terminally differentiated cells. The restoration of sensory function with the return of ciliation translated into a rescue of glomerular activity in the OB. This approach offers perhaps the best current therapeutic option for restoring olfactory dysfunctions. Work in the Martens’ lab now extends to additional ciliopathy models of olfactory loss and includes the use of new clinically relevant viral vectors. However, there is much work that must be done to move this work forward toward clinical trials in patients.

Understanding the penetrance of congenital disorders in the olfactory system and their mechanism of olfactory loss continues to be a fundamental component of preclinical work. This includes further establishment and validation of animal models of anosmia. For example, related to congenital loss, ciliopathy disorders such as Bardet–Biedel syndrome and Joubert syndrome warrant further studies, as do other disorder such as channelopathies (Weiss et al. 2011). Importantly, work should move beyond restoration of olfactory sensory neuron function toward examining the extent to which intranasal gene therapy restores central circuitry, processing and behavioral outputs. For preclinical studies using gene therapy, such methodology needs to evaluate and optimize selectivity and specificity. These should include vector optimization and utilization of olfactory or neuronal specific promoters. In addition, studies to quantitate biodistribution, toxicity, and immunogenicity in rodent and nonhuman primate models will need to be performed.

To translate this work to patients, a number of additional considerations need to be addressed. These include the optimization of treatment delivery such as intranasal versus systemic administration as well as establishing a therapeutic window. Factors including dosage, age of delivery, the persistence of gene-expression over time, and the frequency of delivery need to be tested. The current lack of diagnostic tools to identify the precise mechanism of olfactory loss in patients is also a significant limiting factor. Despite these challenges and the need for more research, gene therapeutic approaches offer a personalized medicine approach with tremendous promise for congenital olfactory loss. These latter issues may merit targeting other cell populations such as olfactory basal stem cells for stable incorporation. Targeting the stem cells of the olfactory epithelium may permit a one-time curative treatment, if therapeutic strategies are restricted to neuron populations that naturally turnover, by-passing the requirement of long-term redosing.

Olfactory stem cells and their potential for restoration of olfactory function

The olfactory epithelium is one of the few sites in the adult nervous system containing neural stem cells that support active neurogenesis over the lifetime of the animal. Olfactory sensory neurons normally turn over every 30–60 days and are replaced through the proliferation and differentiation of a series of immature precursors and multipotent progenitor cells (Graziadei and Montigraziadei 1979). Two classes of multipotent progenitor cells exist in the postnatal olfactory epithelium: the horizontal basal cells (HBCs) and globose basal cells (GBCs). GBCs are actively mitotic and support the normal replacement of sensory neurons and other cell types in the olfactory epithelium. In contrast, HBCs are largely quiescent under steady state conditions. Following injury that results in the destruction of mature cells in the olfactory epithelium, HBCs are stimulated to proliferate and differentiate into GBCs and all mature olfactory cell types (Leung et al. 2007; Iwai et al. 2008). In one model, the HBCs represent a reserve stem cell pool whose constituents divide infrequently under normal conditions to replenish the pool of more actively dividing GBCs (Duggan and Ngai 2007); in response to injury, the HBCs proliferate more vigorously to reconstitute all cellular constituents of this sensory epithelium. Olfactory progenitor cells therefore provide potential therapeutic avenues for cell replacement strategies aimed at restoring olfactory function through regeneration of olfactory sensory neurons. Can olfactory stem cells somehow be used to restore or protect olfactory function in hyposmic and anosmic conditions?

It is important to note that proliferative olfactory progenitors progressively decline in number with age, whereas HBCs remain, albeit in a mostly quiescent state (Weiler and Farbman 1997; Kondo et al. 2010). One approach for harnessing olfactory progenitor/stem cells for regenerating olfactory sensory function might involve activating or “awakening” the quiescent HBCs in situ to differentiate into proliferating GBC progenitors (Schwob et al. 2016). Such an approach would be guided and accelerated by an understanding of the molecular and cellular mechanisms governing olfactory stem cell dynamics. To this end, previous studies identified the transcriptional repressor Trp63 (also known as p63) as a key regulator of HBC self-renewal and differentiation (Fletcher et al. 2011); downregulation of Trp63 is both necessary and sufficient to induce differentiation of HBCs under steady state conditions (Fletcher et al. 2011; Schnittke et al. 2015). Thus, an informed search for the downstream targets of Trp63 and the mechanisms regulating Trp63 expression, as well as other regulatory pathways (e.g., Goldstein et al. 2016; Packard et al. 2016), may yield additional molecular targets for stimulating differentiation and neurogenesis in the olfactory epithelium stem cell niche. Assuming that olfactory neurogenesis can be successfully induced in a therapeutic context, the next set of challenges will entail ensuring appropriate expression of odorant receptor genes and the formation of proper odorant receptor-specific connections in the OB. Nonetheless, recent insights into the regulation of olfactory neurogenesis from adult stem cells in animal models in vivo provide some hope for restoring olfactory function in humans suffering from olfactory sensory deficits.

Conclusions and recommendations

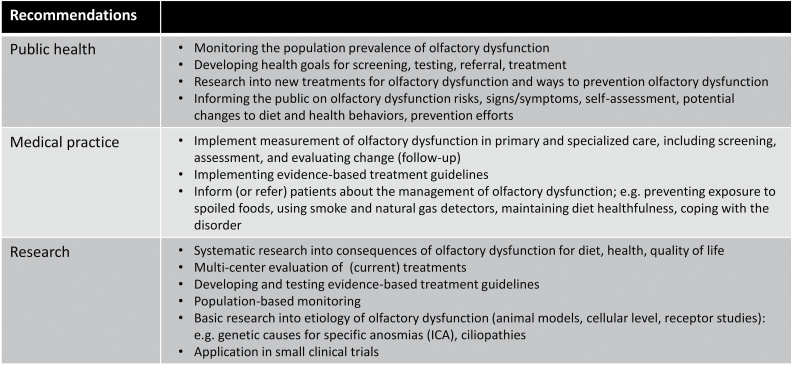

It is clear that even though remarkable progress has been made in the past years, anosmia is yet to be further elucidated, including specifying genetic and environmental risk factors, better diagnosis, and differentiation between the underlying causes and consequent neuronal changes, to greater understanding of the fundamental mechanisms that may lead to potential treatment. For an overview of the present challenges and recommendations, see Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Recommendations.

Olfactory loss requires medical evaluation. It can be an early marker for developing neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinson’s disease or Alzheimer’s disease (e.g., see Ponsen et al. 2004; Rahayel et al. 2012; Ottaviano et al. 2016), increases the risk of malnutrition, safety problems, and has been associated with increased mortality among older adults (Pinto et al. 2014; Ekstrom et al. 2017). From a public health perspective, continued monitoring of the prevalence of olfactory impairment is paramount to increase knowledge of risk factors and track changes with prevention and treatment efforts. Public health goals for assessing, screening, diagnosis, treating, and managing olfactory disorders should be written and/or strengthened. Recommendations for community screening involve a multitier approach, starting with survey questions (see Figure 1), particularly for older adults, and in case olfactory impairment is suspected, brief olfactory testing should follow. General information should be targeted toward older adults on the risks of olfactory dysfunction for maintaining diet healthfulness, quality of life, and avoiding the ingestion of spoiled foods and exposure to smoke and natural gas.

For a clinical setting, full evaluation of olfactory functioning, including both subjective and objective testing, is recommended to characterize the type and severity of the olfactory dysfunction. Patients should be provided with results of objective smell tests and a clear diagnosis. Moreover, information regarding the cause and nature of olfactory loss is important for prognosis and treatment options. ENT physicians should be able to provide this or refer patients early on to specialized smell and taste centers. Further systematic research needs to be undertaken on the influence of smell loss on eating behavior in order to identify changes in food preferences and food intake among patients. This knowledge could be used to advice anosmic patients on how to cope with the loss of their sense of smell with respect to their dietary behaviors to improve their health and nutritional status. Advice regarding safety and how to prevent possible hazardous events (e.g., smoke or gas alert) should be given.

Olfactory training appears to be a promising therapy for patients with postviral olfactory loss to partly regain their sense of smell (Pekala et al. 2016; Sorokowska et al. 2017). Given the neural reorganization that takes place here, future research should also look at longitudinal changes. Combining different neuroimaging methods, structural and functional, may lead to insight in more subtle reorganization processes and will possibly foster the development of biomarkers to predict therapy success in the future.

To reiterate, the plethora of etiologies underlying olfactory loss makes the disease complex to understand and treat. Different causes require different approaches, and differentiation between types of olfactory loss is crucial to advance the field further. Basic research should fuel advances in the fundamental mechanisms underlying specific anosmias, such as ICA, and ciliopathies. Identification of the genetic basis of ICA will help with diagnosis, prognosis, and possible treatment of congenital anosmia, given that the olfactory neurons are relatively easily accessible in the nasal cavity. Fundamental work should also include establishment and validation of animal models of anosmia and go beyond merely restoring olfactory sensory neuron function to investigate how this alters central circuitry, processing, and behavioral outputs, in parallel to human studies. Potentially, olfactory stem cells could provide therapeutic use, to restore or protect olfactory function. If olfactory neurogenesis can be successfully induced in a therapeutic context, further research should focus on odorant receptor gene expression and the formation of proper odorant receptor-specific connections in the OB. Understanding the etiology as well as the cellular level at which the defects occur is critical for choosing the appropriate therapy.

Finally, establishing educational and clinical programs that inform patients about diagnostic and treatment options and can also identify viable patient populations for treatment is an advanced piece of the puzzle. For example, the University of Florida Center for Smell and Taste is partnering with the United Kingdom-based charity, Fifth Sense, in new activities—including the patient-focused conference SmellTaste2017—to educate patients about chemosensory disorders, their diagnosis and potential treatments, and strategies for getting peer and medical support. Also, the Monell Chemical Senses Center has initiated the Monell Anosmia Project to identify the basic mechanisms of human olfactory stem cell regeneration and learn more about the genes underlying anosmia, and includes patient participation and activities to raise awareness. These and other fundamental advances indeed give hope for future clinical trials and potentially treatment.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant [DC013339 to J.D.M., DC007235 to J.N.] and the Monell Anosmia Project (J.D.M.).

References

- Adams DR, Wroblewski KE, Kern DW, Kozloski MJ, Dale W, McClintock MK, Pinto JM. 2016. Factors associated with inaccurate self-reporting of olfactory dysfunction in older US adults. Chem Senses. 41:E58–E58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkelai A, Olender T, Haffner-Krausz R, Tsoory MM, Boyko V, Tatarskyy P, Gross-Isseroff R, Milgrom R, Shushan S, Blau I, et al. 2016. A role for TENM1 mutations in congenital general anosmia. Clin Genet. 90:211–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altundag A, Cayonu M, Kayabasoglu G, Salihoglu M, Tekeli H, Saglam O, Hummel T. 2015. Modified olfactory training in patients with postinfectious olfactory loss. Laryngoscope. 125:1763–1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aschenbrenner K, Hummel C, Teszmer K, Krone F, Ishimaru T, Seo HS, Hummel T. 2008. The influence of olfactory loss on dietary behaviors. Laryngoscope. 118:135–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Askew C, Rochat C, Pan BF, Asai Y, Ahmed H, Child E, Schneider BL, Aebischer P, Holt JR. 2015. Tmc gene therapy restores auditory function in deaf mice. Sci Transl Med. 7:295ra108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banglawala SM, Oyer SL, Lohia S, Psaltis AJ, Soler ZM, Schlosser RJ. 2014. Olfactory outcomes in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis after medical treatments: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 4:986–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benninger MS, Hadley JA, Osguthorpe JD, Marple BF, Leopold DA, Derebery MJ, Hannley M. 2004. Techniques of intranasal steroid use. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 130:5–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitter T, Brüderle J, Gudziol H, Burmeister HP, Gaser C, Guntinas-Lichius O. 2010. Gray and white matter reduction in hyposmic subjects – a voxel-based morphometry study. Brain Res. 1347:42–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitter T, Gudziol H, Burmeister HP, Mentzel HJ, Guntinas-Lichius O, Gaser C. 2010. Anosmia leads to a loss of gray matter in cortical brain areas. Chem Senses. 35(5):407–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomqvist EH, Brämerson A, Stjärne P, Nordin S. 2004. Consequences of olfactory loss and adopted coping strategies. Rhinology. 42:189–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boesveldt S, Boak D, Welge-Luessen A, Ngai J, Martens JR. 2016. Clinical symposium: anosmia – the patient, the clinic, the cure? Chem Senses. 41:e5–e6. [Google Scholar]

- Boesveldt S, De Graaf C.Forthcoming 2017. The differential role of smell and taste for eating behavior. Perception. 46(3-4). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boesveldt S, Postma E, Boek W, de Graaf K. 2015. Smell and taste disorders – current care and treatment in the Dutch health care system. Chem Senses. 40:623–624. [Google Scholar]

- Boesveldt S, Yee JR, McClintock MK, Lundström JN. 2017. Olfactory function and the social lives of older adults: a matter of sex. Sci Rep. 7:45118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner EA, Mainland JD, Khan RM, Sobel N. 2003. The prevalence of androstenone anosmia. Chem Senses. 28:423–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bruijn SEM, de Vries YC, de Graaf C, Boesveldt S, Jager G. 2017. The reliability and validity of the Macronutrient and Taste Preference Ranking Task: a new method to measure food preferences. Food Qual Prefer. 57:32–40. [Google Scholar]

- Cain WS. 1979. To know with the nose: keys to odor identification. Science. 203:467–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croy I, Nordin S, Hummel T. 2014. Olfactory disorders and quality of life – an updated review. Chem Senses. 39:185–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croy I, Olgun S, Mueller L, Schmidt A, Muench M, Hummel C, Gisselmann G, Hatt H, Hummel T. 2015. Peripheral adaptive filtering in human olfaction? Three studies on prevalence and effects of olfactory training in specific anosmia in more than 1600 participants. Cortex. 73:180–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damm M, Pikart LK, Reimann H, Burkert S, Göktas Ö, Haxel B, Frey S, Charalampakis I, Beule A, Renner B, et al. 2014. Olfactory training is helpful in postinfectious olfactory loss: a randomized, controlled, multicenter study. Laryngoscope. 124:826–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damm M, Temmel A, Welge-Lüssen A, Eckel HE, Kreft MP, Klussmann JP, Gudziol H, Hüttenbrink KB, Hummel T. 2004. Olfactory dysfunctions. Epidemiology and therapy in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. HNO. 52:112–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilisio MF. 2014. Osteonecrosis following short-term, low-dose oral corticosteroids: a population-based study of 24 million patients. Orthopedics. 37:e631–e636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dode C, Hardelin JP. 2010. Clinical genetics of Kallmann syndrome. Ann Endocrinol (Paris). 71:149–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dode C, Levilliers J, Dupont JM, De Paepe A, Le Dû N, Soussi-Yanicostas N, Coimbra RS, Delmaghani S, Compain-Nouaille S, Baverel F, et al. 2003. Loss-of-function mutations in FGFR1 cause autosomal dominant Kallmann syndrome. Nat Genet. 33:463–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dode C, Teixeira L, Levilliers J, Fouveaut C, Bouchard P, Kottler ML, Lespinasse J, Lienhardt-Roussie A, Mathieu M, Moerman A, et al. 2006. Kallmann syndrome: mutations in the genes encoding prokineticin-2 and prokineticin receptor-2. PLoS Genet. 2:1648–1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doty RL, Shaman P, Applebaum SL, Giberson R, Siksorski L, Rosenberg L. 1984. Smell identification ability: changes with age. Science. 226:1441–1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doty RL, Shaman P, Kimmelman CP, Dann MS. 1984. University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test: a rapid quantitative olfactory function test for the clinic. Laryngoscope. 94:176–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy VB, Backstrand JR, Ferris AM. 1995. Olfactory dysfunction and related nutritional risk in free-living, elderly women. J Am Diet Assoc. 95:879–84; quiz 885–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy VB, Hayes JE. 2014. Smell, taste, and oral somatosensation: age-related changes and nutritional implications. In: Chernoff R, editor. Geriatric nutrition: the health professional’s handbook. 4th ed. Burlington (MA): Jones and Bartlett Publishers; p. 115–164. [Google Scholar]

- Duggan CD, Ngai J. 2007. Scent of a stem cell. Nat Neurosci. 10:673–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrom I, Sjolund S, Nordin S, Adolfsson AN, Adolfsson R, Nilsson LG, Larsson M, Olofsson JK. 2017. Smell loss predicts mortality risk regardless of dementia conversion. J Am Geriatr Soc. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falardeau J, Chung WC, Beenken A, Raivio T, Plummer L, Sidis Y, Jacobson-Dickman EE, Eliseenkova AV, Ma J, Dwyer A, et al. 2008. Decreased FGF8 signaling causes deficiency of gonadotropin-releasing hormone in humans and mice. J Clin Invest. 118:2822–2831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fark T, Hummel C, Hähner A, Nin T, Hummel T. 2013. Characteristics of taste disorders. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 270:1855–1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldmesser E, Bercovich D, Avidan N, Halbertal S, Haim L, Gross-Isseroff R, Goshen S, Lancet D. 2007. Mutations in olfactory signal transduction genes are not a major cause of human congenital general anosmia. Chem Senses. 32:21–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferris AM, Duffy VB. 1989. Effect of olfactory deficits on nutritional status. Does age predict persons at risk? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 561:113–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher RB, Prasol MS, Estrada J, Baudhuin A, Vranizan K, Choi YG, Ngai J. 2011. p63 regulates olfactory stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. Neuron. 72:748–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco B, Guioli S, Pragliola A, Incerti B, Bardoni B, Tonlorenzi R, Carrozzo R, Maestrini E, Pieretti M, Taillon-Miller P, et al. 1991. A gene deleted in Kallmann’s syndrome shares homology with neural cell adhesion and axonal path-finding molecules. Nature. 353:529–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasnelli J, Hummel T. 2005. Olfactory dysfunction and daily life. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 262:231–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasnelli J, Hummel T. 2007. Interactions between the chemical senses: trigeminal function in patients with olfactory loss. Int J Psychophysiol. 65:177–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii M, Fukazawa K, Takayasu S, Sakagami M. 2002. Olfactory dysfunction in patients with head trauma. Auris Nasus Larynx. 29:35–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg YP, MacFarlane J, MacDonald ML, Thompson J, Dube MP, Mattice M, Fraser R, Young C, Hossain S, Pape T, et al. 2007. Loss-of-function mutations in the Nav1.7 gene underlie congenital indifference to pain in multiple human populations. Clin Genet. 71:311–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein BJ, Goss GM, Choi R, Saur D, Seidler B, Hare JM, Chaudhari N. 2016. Contribution of Polycomb group proteins to olfactory basal stem cell self-renewal in a novel c-KIT+ culture model and in vivo. Development. 143:4394–4404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopinath B, Anstey KJ, Sue CM, Kifley A, Mitchell P. 2011. Olfactory impairment in older adults is associated with depressive symptoms and poorer quality of life scores. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 19:830–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graziadei PPC, Montigraziadei GA. 1979. Neurogenesis and neuron regeneration in the olfactory system of mammals. 1. Morphological aspects of differentiation and structural organization of the olfactory sensory neurons. J Neurocytol. 8:1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haehner A, Tosch C, Wolz M, Klingelhoefer L, Fauser M, Storch A, Reichmann H, Hummel T. 2013. Olfactory training in patients with Parkinson’s disease. PLoS One. 8:e61680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardelin JP, Dode C. 2008. The complex genetics of Kallmann syndrome: KAL1, FGFR1, FGF8, PROKR2, PROK2, et al. Sex Dev. 2:181–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman HJ, Rawal S, Li CM, Duffy VB. 2016. New chemosensory component in the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES): first-year results for measured olfactory dysfunction. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 17:221–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huart C, Rombaux P, Hummel T. 2013. Plasticity of the human olfactory system: the olfactory bulb. Molecules. 18:11586–11600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummel T, Kobal G, Gudziol H, Mackay-Sim A. 2007. Normative data for the “Sniffin’ Sticks” including tests of odor identification, odor discrimination, and olfactory thresholds: an upgrade based on a group of more than 3,000 subjects. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 264:237–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummel T, Nordin S. 2005. Olfactory disorders and their consequences for quality of life. Acta Otolaryngol. 125:116–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummel T, Rissom K, Reden J, Hähner A, Weidenbecher M, Hüttenbrink KB. 2009. Effects of olfactory training in patients with olfactory loss. Laryngoscope. 119:496–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummel T, Sekinger B, Wolf SR, Pauli E, Kobal G. 1997. ‘Sniffin’ sticks’: olfactory performance assessed by the combined testing of odor identification, odor discrimination and olfactory threshold. Chem Senses. 22:39–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummel T, Welge-Luessen A. 2006. Assessment of olfactory function. In: Hummel T, Welge-Luessen A, editors. Advances in oto-rhino-laryngology: taste and smell, an update. Basel (Switzerland): Karger; p. 84–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iannaccone A, Mykytyn K, Persico AM, Searby CC, Baldi A, Jablonski MM, Sheffield VC. 2005. Clinical evidence of decreased olfaction in Bardet-Biedl syndrome caused by a deletion in the BBS4 gene. Am J Med Genet A. 132A:343–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iannilli E, Gerber J, Frasnelli J, Hummel T. 2007. Intranasal trigeminal function in subjects with and without an intact sense of smell. Brain Res. 1139:235–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwai N, Zhou Z, Roop DR, Behringer RR. 2008. Horizontal basal cells are multipotent progenitors in normal and injured adult olfactory epithelium. Stem Cells. 26:1298–1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jafek BW, Moran DT, Eller PM, Rowley JC, 3rd, Jafek TB. 1987. Steroid-dependent anosmia. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 113:547–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang RS, Twu CW, Liang KL. 2015. Medical treatment of traumatic anosmia. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 152:954–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang RS, Wu SH, Liang KL, Shiao JY, Hsin CH, Su MC. 2010. Steroid treatment of posttraumatic anosmia. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 267:1563–1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jongmans MC, van Ravenswaaij-Arts CM, Pitteloud N, Ogata T, Sato N, Claahsen-van der Grinten HL, van der Donk K, Seminara S, Bergman JE, Brunner HG, et al. 2009. CHD7 mutations in patients initially diagnosed with Kallmann syndrome – the clinical overlap with CHARGE syndrome. Clin Genet. 75:65–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karstensen HG, Mang Y, Fark T, Hummel T, Tommerup N. 2015. The first mutation in CNGA2 in two brothers with anosmia. Clin Genet. 88:293–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katotomichelakis M, Riga M, Davris S, Tripsianis G, Simopoulou M, Nikolettos N, Simopoulos K, Danielides V. 2009. Allergic rhinitis and aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease as predictors of the olfactory outcome after endoscopic sinus surgery. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 23:348–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller A, Malaspina D. 2013. Hidden consequences of olfactory dysfunction: a patient report series. BMC Ear Nose Throat Disord. 13:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern DW, Wroblewski KE, Schumm LP, Pinto JM, Chen RC, McClintock MK. 2014. Olfactory function in Wave 2 of the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 69:S134–S143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HG, Kurth I, Lan F, Meliciani I, Wenzel W, Eom SH, Kang GB, Rosenberger G, Tekin M, Ozata M, et al. 2008. Mutations in CHD7, encoding a chromatin-remodeling protein, cause idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and Kallmann syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 83:511–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimek L, Poletti SC, Sperl A, Spielhaupter M, Bardenhewer C, Mullol J, Hörmann K, Hummel T. 2017. Olfaction in patients with allergic rhinitis: an indicator of successful MP-AzeFlu therapy. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 7:287–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knaapila A, Zhu G, Medland SE, Wysocki CJ, Montgomery GW, Martin NG, Wright MJ, Reed DR. 2012. A genome-wide study on the perception of the odorants androstenone and galaxolide. Chem Senses. 37:541–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi M, Costanzo RM. 2009. Olfactory nerve recovery following mild and severe injury and the efficacy of dexamethasone treatment. Chem Senses. 34:573–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollndorfer K, Fischmeister FP, Kowalczyk K, Hoche E, Mueller CA, Trattnig S, Schöpf V. 2015. Olfactory training induces changes in regional functional connectivity in patients with long-term smell loss. Neuroimage Clin. 9:401–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollndorfer K, Jakab A, Mueller CA, Trattnig S, Schöpf V. 2015. Effects of chronic peripheral olfactory loss on functional brain networks. Neuroscience. 310:589–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollndorfer K, Kowalczyk K, Hoche E, Mueller CA, Pollak M, Trattnig S, Schöpf V. 2014. Recovery of olfactory function induces neuroplasticity effects in patients with smell loss. Neural Plast. 2014:140419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollndorfer K, Reichert JL, Bruckler B, Hinterleitner V, Schöpf V. 2017. Self-esteem as an important factor in quality of life and depressive symptoms in anosmia: a pilot study. Clin Otolaryngol. doi: 10.1111/coa.12855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo K, Suzukawa K, Sakamoto T, Watanabe K, Kanaya K, Ushio M, Yamaguchi T, Nibu K, Kaga K, Yamasoba T. 2010. Age-related changes in cell dynamics of the postnatal mouse olfactory neuroepithelium: cell proliferation, neuronal differentiation, and cell death. J Comp Neurol. 518:1962–1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konstantinidis I, Tsakiropoulou E, Bekiaridou P, Kazantzidou C, Constantinidis J. 2013. Use of olfactory training in post-traumatic and postinfectious olfactory dysfunction. Laryngoscope. 123:E85–E90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremer S, Bult JH, Mojet J, Kroeze JH. 2007. Compensation for age-associated chemosensory losses and its effect on the pleasantness of a custard dessert and a tomato drink. Appetite. 48:96–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremer S, Holthuysen NTE, Boesveldt S. 2014. The influence of olfactory impairment in vital, independent living elderly on their eating behaviour and food liking. Food Qual Prefer. 38:30–39. [Google Scholar]

- Kulaga HM, Leitch CC, Eichers ER, Badano JL, Lesemann A, Hoskins BE, Lupski JR, Beales PL, Reed RR, Katsanis N. 2004. Loss of BBS proteins causes anosmia in humans and defects in olfactory cilia structure and function in the mouse. Nat Genet. 36:994–998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis BN, Stow NW, Lacroix JS, Hugentobler M, Hummel T. 2009. Olfactory disorders: the patients’ view. Rhinology. 47:454–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Lee L, Geelen A, van Huysduynen EJCH, de Vries JHM, van’t Veer P, Feskens EJM. 2012. The Dutch Healthy Diet index (DHD-index): an instrument to measure adherence to the Dutch Guidelines for a Healthy Diet. Nutr J. 11:49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legouis R, Hardelin JP, Levilliers J, Claverie JM, Compain S, Wunderle V, Millasseau P, Le Paslier D, Cohen D, Caterina D. 1991. The candidate gene for the X-linked Kallmann syndrome encodes a protein related to adhesion molecules. Cell. 67:423–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung CT, Coulombe PA, Reed RR. 2007. Contribution of olfactory neural stem cells to tissue maintenance and regeneration. Nat Neurosci. 10:720–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotsch J, Reither N, Bogdanov V, Hähner A, Ultsch A, Hill K, Hummel T. 2015. A brain-lesion pattern based algorithm for the diagnosis of posttraumatic olfactory loss. Rhinology. 53:365–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundström JN, Boesveldt S, Albrecht J. 2011. Central processing of the chemical senses: an overview. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2:5–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mainland JD, Bremner EA, Young N, Johnson BN, Khan RM, Bensafi M, Sobel N. 2002. Olfactory plasticity: one nostril knows what the other learns. Nature. 419:802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malaty J, Malaty IA. 2013. Smell and taste disorders in primary care. Am Fam Phys. 88:852–859. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre JC, Davis EE, Joiner A, Williams CL, Tsai IC, Jenkins PM, McEwen DP, Zhang L, Escobado J, Thomas S, et al. 2012. Gene therapy rescues cilia defects and restores olfactory function in a mammalian ciliopathy model. Nat Med. 18:1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre JC, Williams CL, Martens JR. 2013. Smelling the roses and seeing the light: gene therapy for ciliopathies. Trends Biotechnol. 31:355–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miraoui H, Dwyer AA, Sykiotis GP, Plummer L, Chung W, Feng B, Beenken A, Clarke J, Pers TH, Dworzynski P, et al. 2013. Mutations in FGF17, IL17RD, DUSP6, SPRY4, and FLRT3 are identified in individuals with congenital hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Am J Hum Genet. 92:725–743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori E, Merkonidis C, Cuevas M, Gudziol V, Matsuwaki Y, Hummel T. 2016. The administration of nasal drops in the “Kaiteki” position allows for delivery of the drug to the olfactory cleft: a pilot study in healthy subjects. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 273:939–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moya-Plana A, Villanueva C, Laccourreye O, Bonfils P, de Roux N. 2013. PROKR2 and PROK2 mutations cause isolated congenital anosmia without gonadotropic deficiency. Eur J Endocrinol. 168:31–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy C, Schubert CR, Cruickshanks KJ, Klein BE, Klein R, Nondahl DM. 2002. Prevalence of olfactory impairment in older adults. JAMA. 288:2307–2312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen DT, Bey A, Arous F, Nguyen-Thi PL, Felix-Ravelo M, Jankowski R. 2015. Can surgeons predict the olfactory outcomes after endoscopic surgery for nasal polyposis? Laryngoscope. 125:1535–1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen KB, Nicholas AK, Woods CG, Mellgren SI, Nebuchennykh M, Aasly J. 2009. Two novel SCN9A mutations causing insensitivity to pain. Pain. 143:155–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordin S, Brämerson A. 2008. Complaints of olfactory disorders: epidemiology, assessment and clinical implications. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 8:10–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottaviano G, Frasson G, Nardello E, Martini A. 2016. Olfaction deterioration in cognitive disorders in the elderly. Aging Clin Exp Res. 28:37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packard AI, Lin B, Schwob JE. 2016. Sox2 and Pax6 play counteracting roles in regulating neurogenesis within the murine olfactory epithelium. PLoS One. 11:e0155167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson A, Hähner A, Kitzler HH, Hummel T. 2015. Are small olfactory bulbs a risk for olfactory loss following an upper respiratory tract infection? Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 272:3593–3594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pekala K, Chandra RK, Turner JH. 2016. Efficacy of olfactory training in patients with olfactory loss: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 6:299–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pence TS, Reiter ER, DiNardo LJ, Costanzo RM. 2014. Risk factors for hazardous events in olfactory-impaired patients. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 140:951–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng P, Gu H, Xiao W, Si LF, Wang JF, Wang SK, Zhai RY, Wei YX. 2013. A voxel-based morphometry study of anosmic patients. Brit J Radiol. 86:20130207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philpott CM, Boak D. 2014. The impact of olfactory disorders in the United kingdom. Chem Senses. 39:711–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philpott C, DeVere D. 2014. Postinfectious and post-traumatic olfactory disorders. In: Welge-Luessen A, Hummel T, editors. Management of smell and taste disorders. New York: Thieme; p. 91–105. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto JM, Wroblewski KE, Kern DW, Schumm LP, McClintock MK. 2014. Olfactory dysfunction predicts 5-year mortality in older adults. PLoS One. 9:e107541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponsen MM, Stoffers D, Booij J, van Eck-Smit BL, Wolters ECH, Berendse HW. 2004. Idiopathic hyposmia as a preclinical sign of Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol. 56:173–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Promotion USOoDPaH 2017. Healthy People 2020 objectives—Hearing and other sensory or communication disorders. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Available at: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/hearing-and-other-sensory-or-communication-disorders/objectives (accessed 8 May 2017).

- Rahayel S, Frasnelli J, Joubert S. 2012. The effect of Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease on olfaction: a meta-analysis. Behav Brain Res. 231:60–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawal S, Hoffman HJ, Bainbridge KE, Huedo-Medina TB, Duffy VB. 2016. Prevalence and risk factors of self-reported smell and taste alterations: results from the 2011–2012 US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Chem Senses. 41:69–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawal S, Hoffman HJ, Honda M, Huedo-Medin TB, Duffy VB. 2015. The taste and smell protocol in the 2011-2014 US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES): test-retest reliability and validity testing. Chemosens Percept. 8:138–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reden J, Lill K, Zahnert T, Haehner A, Hummel T. 2012. Olfactory function in patients with postinfectious and posttraumatic smell disorders before and after treatment with vitamin A: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. Laryngoscope. 122:1906–1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichert JL, Schöpf V. 2017. Olfactory loss and regain: lessons for neuroplasticity. The Neuroscientist. doi:10.1177/1073858417703910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter E, Constanzo RM. 2003. The overlooked impact of olfactory loss; safety, quality of life and disability issues. Chem Senses. 6:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Rimmer J, Fokkens W, Chong LY, Hopkins C. 2014. Surgical versus medical interventions for chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. CD006991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rombaux P, Duprez T, Hummel T. 2009. Olfactory bulb volume in the clinical assessment of olfactory dysfunction. Rhinology. 47:3–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rombaux P, Huart C, Deggouj N, Duprez T, Hummel T. 2012. Prognostic value of olfactory bulb volume measurement for recovery in postinfectious and posttraumatic olfactory loss. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 147:1136–1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahel JA, Marazova K, Audo I. 2015. Clinical characteristics and current therapies for inherited retinal degenerations. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 5:a017111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos DV, Reiter ER, DiNardo LJ, Costanzo RM. 2004. Hazardous events associated with impaired olfactory function. Arch Otolaryngol. 130:317–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheibe M, Bethge C, Witt M, Hummel T. 2008. Intranasal administration of drugs. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 134:643–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnittke N, Herrick DB, Lin B, Peterson J, Coleman JH, Packard AI, Jang W, Schwob JE. 2015. Transcription factor p63 controls the reserve status but not the stemness of horizontal basal cells in the olfactory epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 112:E5068–E5077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schöpf V, Kollndorfer K. 2015. Clinical assessment of olfactory performance – why patient interviews are not enough: a report on lessons learned in planning studies with anosmic patients. HNO. 63:511–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwob JE, Jang W, Holbrook EH, Lin B, Herrick DB, Peterson JN, Hewitt Coleman J. 2016. Stem and progenitor cells of the mammalian olfactory epithelium: taking poietic license. J Comp Neurol. 525(4):1034–1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seok J, Shim YJ, Rhee CS, Kim JW. 2017. Correlation between olfactory severity ratings based on olfactory function test scores and self-reported severity rating of olfactory loss. Acta Otolaryngol. doi: 10.1080/00016489.2016.1277782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivam A, Wroblewski KE, Alkorta-Aranburu G, Barnes LL, Wilson RS, Bennett DA, Pinto JM. 2016. Olfactory dysfunction in older adults is associated with feelings of depression and loneliness. Chem Senses. 41:293–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soler ZM, Sauer DA, Mace JC, Smith TL. 2010. Ethmoid histopathology does not predict olfactory outcomes after endoscopic sinus surgery. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 24:281–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorokowska A, Drechsler E, Karwowski M, Hummel T. 2017. Effects of olfactory training: a meta-analysis. Rhinology. 55(1):17–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson RJ. 2010. An initial evaluation of the functions of human olfaction. Chem Senses. 35:3–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuck BA, Blum A, Hagner AE, Hummel T, Klimek L, Hörmann K. 2003. Mometasone furoate nasal spray improves olfactory performance in seasonal allergic rhinitis. Allergy. 58:1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadenev AL, Kulaga HM, May-Simera HL, Kelley MW, Katsanis N, Reed RR. 2011. Loss of Bardet-Biedl syndrome protein-8 (BBS8) perturbs olfactory function, protein localization, and axon targeting. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 108:10320–10325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temmel AFP, Quint C, Schickinger-Fischer B, Klimek L, Stoller E, Hummel T. 2002. Characteristics of olfactory disorders in relation to major causes of olfactory loss. Arch Otolaryngol. 128:635–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toussaint N, de Roon M, van Campen JP, Kremer S, Boesveldt S. 2015. Loss of olfactory function and nutritional status in vital older adults and geriatric patients. Chem Senses. 40:197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Camp G, Smith R. 2016. The Hereditary Hearing loss Homepage. Available from: http://hereditaryhearingloss.org/ (accessed 10 May 2017). [Google Scholar]

- Vuorela PE, Penttinen MT, Hietala MH, Laine JO, Huoponen KA, Kääriäinen HA. 2008. A familial CHARGE syndrome with a CHD7 nonsense mutation and new clinical features. Clin Dysmorphol. 17:249–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehling E, Nordin S, Espeseth T, Reinvang I, Lundervold AJ. 2011. Unawareness of olfactory dysfunction and its association with cognitive functioning in middle aged and old adults. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 26:260–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiler E, Farbman AI. 1997. Proliferation in the rat olfactory epithelium: age-dependent changes. J Neurosci. 17:3610–3622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss J, Pyrski M, Jacobi E, Bufe B, Willnecker V, Schick B, Zizzari P, Gossage SJ, Greer CA, Leinders-Zufall T, et al. 2011. Loss-of-function mutations in sodium channel Nav1.7 cause anosmia. Nature. 472:186–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welge-Luessen A, Hummel T. 2013. Management of smell and taste disorders: a practical guide for clinicians. New York: Thieme. [Google Scholar]

- Welge-Luessen A, Leopold DA, Miwa T. 2014. Smell and taste disorders-diagnostic and clinical work-up. In: Welge-Luessen A, Hummel T, editors. Management of smell and taste disorders: a practical guide for clinicians. New York: Thieme; p. 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Whitcroft KL, Merkonidis C, Cuevas M, Haehner A, Philpott C, Hummel T. 2016. Intranasal sodium citrate solution improves olfaction in post-viral hyposmia. Rhinology. 54:368–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DA, Best AR, Sullivan RM. 2004. Plasticity in the olfactory system: lessons for the neurobiology of memory. Neuroscientist. 10:513–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao L, Pinto JM, Yi X, Li L, Peng P, Wei Y. 2014. Gray matter volume reduction of olfactory cortices in patients with idiopathic olfactory loss. Chem Senses. 39:755–760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee KK, Pribitkin EA, Cowart BJ, Vainius AA, Klock CT, Rosen D, Feng P, McLean J, Hahn CG, Rawson NE. 2010. Neuropathology of the olfactory mucosa in chronic rhinosinusitis. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 24:110–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]