Abstract

Since the 1980s, black persons have been overrepresented in the United States homeless population. Given that morbidity and mortality is elevated among both the black population and the homeless population in comparison to the general U.S. population, this overrepresentation has important implications for health policy. However, the racial demographics of homelessness have received little attention from policymakers. This article reviews published social and behavioral science literature that addresses the relationship between race and contemporary homelessness in the United States. This literature points to substantial differences between racial subgroups of the U.S. homeless population in vulnerabilities, health risks, behaviors, and service outcomes. Such observed differences suggest that policies and programs to prevent and end homelessness must explicitly consider race as a factor in order to be of maximum effectiveness. The limited scope of these findings also suggests that more research is needed to better understand these differences and their implications.

Keywords: race, homelessness, poverty

Introduction

In 1985, a groundbreaking study of homelessness in Ohio revealed that black persons1 were significantly overrepresented in this group (Roth, 1985). This study, the first ever systematic survey of homelessness to be conducted across an entire state since the Great Depression, provided empirical support for ethnographers’ earlier observations that profound demographic shifts were occurring in the United States’ homeless population (Baxter & Hopper, 1981). A dwindling cluster consisting primarily of “older white men, who were uneducated and ensnared in alcoholism” (Bachrach, 1984; Hodnicki, 1990, p. 59) was giving way to a new, younger, more racially diverse population of homeless men and women (Baxter & Hopper, 1981). Other research also supported the finding that black persons were overrepresented in the entire U.S. homeless population, over and above the disproportionate percentage of these persons living in poverty (Burt & Cohen, 1989; Farr, Koegel, & Burnham, 1986).

Thirty years later, black persons remain substantially overrepresented in the U.S. homeless population, comprising roughly 40.4 percent of the total U.S. homeless population, but only 12.5 percent of the overall population (United States Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2015; hereafter HUD). Black persons also made up 48.7 percent of homeless persons in families, according to HUD’s 2015 Point-in-Time (PIT) estimates of homelessness (HUD, 2015). An analysis of 2010 data indicated that members of black families were seven times as likely as members of white families to spend time in a homeless shelter (Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness, 2012). Hispanic persons, in contrast, are underrepresented in the homeless population, despite having poverty rates comparable to black persons (Krogstad, 2014).

The enduring overrepresentation of black persons in the U.S. homeless population has serious implications for population health and health disparities. Homeless populations have age-adjusted mortality rates double to triple that of the general population (Barrow, Herman, Cordova, & Streuning, 1999; Hibbs et al., 1994), are at elevated risk of premature death even in comparison to other low-income populations, and suffer disproportionately from a variety of chronic health conditions (O’Connell, 2005). Additionally, the U.S. black population still has an average life expectancy of 3.8 years less than the white population, with higher death rates than the white population for leading causes of death including heart disease, cancer, diabetes, and homicide (Kochanek, Arias, & Anderson, 2013; Williams & Mohammed, 2009). The black homeless population thus likely faces a double dose of vulnerability.

The racial demography of homelessness and its potential implications have received little attention from policymakers. In 2010, the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness (USICH) released Opening Doors, the federal government’s first comprehensive strategic plan to prevent and end homelessness (USICH, 2010). While the plan acknowledged that people face “vulnerabilities associated with race and gender” as well as other factors (USICH, 2010, p. 44), none of its objectives, strategies, or updates explicitly addressed how racial dynamics in homelessness might affect its efforts (USICH, 2010, 2015). Similarly, the National Alliance to End Homelessness (NAEH), a leading nongovernmental organization, has not once mentioned race or racial discrimination in recent editions of its widely distributed yearly report, The State of Homelessness in America (NAEH, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014). While the 2015 Annual Homelessness Assessment Report to Congress (AHAR), released in November 2015 by HUD, does include data on the proportions of the homeless population belonging to black, Hispanic, and white racial/ethnic groups, it remains to be seen whether policy organizations will analyze this data.

A colorblind approach to addressing homelessness would be justified if the risk and protective factors related to homelessness, the pathways into homelessness, and outcomes of services and programs to address homelessness did not differ from one racial group to another. “Race” is only a socio-historical category and is not a means for explaining biological differences between groups (Smedley & Smedley, 2005), and racial discrimination in housing, employment, education, voting, and public accommodations has been illegal in the United States for over 50 years (The Leadership Conference, 2009). Some policymakers might, therefore, object to race-based approaches to addressing homelessness as contrary to values supporting racial equality. However, racial discrimination continues to negatively affect the health of racial and ethnic minorities within the United States (Williams, Neighbors, & Jackson, 2003), and many U.S. cities remain highly racially segregated (Frey, 2014). Strategies to address homelessness that ignore race and the impact of racial discrimination may, therefore, be suboptimal: these strategies may not address major factors that influence individuals’ and families’ pathways into homelessness as well as their success in exiting homelessness. This article reviews social and behavioral science research on the relationship between race, racial discrimination, and homelessness in the United States in order to inform future policies.

Methods

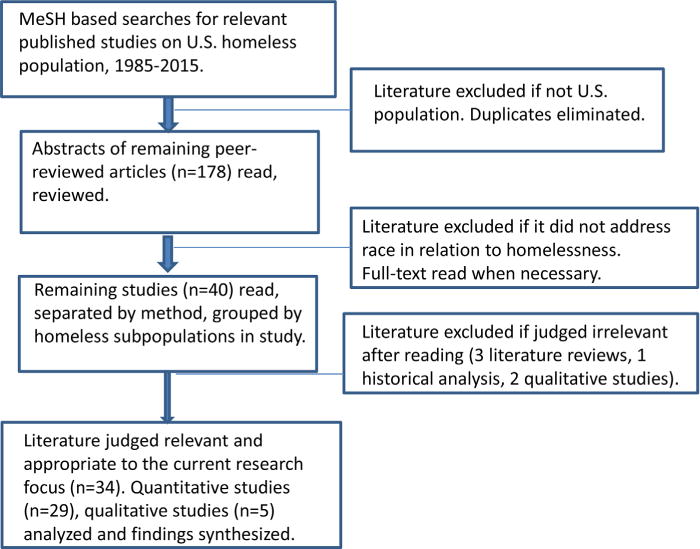

This literature review involved a search of numerous databases for all peer-reviewed publications published in English from January 1985 to May 2015 that related to race and homelessness in the United States. The year 1985 was chosen as a start date because homelessness in the contemporary sense was not recognized by researchers and policymakers until the early 1980s (Jones, 2015). Second, a preliminary online literature search of the meta-search engine Academic Search Premier (EBSCO)—which includes Medline, PsychInfo, and Race Relations—using the search terms “homeless” and “homelessness,” retrieved only one article published on the U.S. homeless populations before 1985, and this article related to legal issues. Thus, a subsequent literature search, which is outlined in Figure 1, was designed to identify the published social and behavioral science literature most relevant to questions of whether and how race and racial discrimination might matter in precipitating and addressing contemporary homelessness within the United States. The following databases were searched: Academic Search Premier (EBSCO), Ethnic Newswatch, JStor Social Sciences, and Google Scholar Advanced Search. Medical Search Headings (MeSH) were used to query these databases. These headings included “homeless persons,” “homelessness,” “homeless youth,” “homeless child,” and “homeless person.” Each of the homelessness-related search terms was paired with the MeSH term “race.” (Searches were tried pairing homelessness-related terms with specific terms related to race, including “whites,” “blacks,” “African Americans,” and “Hispanics,” but these searches did not yield any additional articles.) Searches were designed to retrieve the literature in which the search terms appeared anywhere in a document, including subject and key-word indices. A total of 178 articles were identified. These constituted a small portion of the literature published during this period that included any homelessness-related search terms. A search using the words “homeless OR homelessness” retrieved a total of 6,922 articles for Academic Search Premier, 17,027 for JStor Social Sciences, and 208,000 articles for Google Scholar Advanced Search. The articles identified on race and homelessness thus represented less than 0.08 percent of the total. These searches may have failed to identify some relevant published literature. Yet, even if this is the case, the results reflect how little of the published research on homelessness has examined the possible relationship between race and homelessness.

Figure 1.

Schematic Representation of Literature Acquisition and Review Process.

The search results were next prescreened to exclude all the literature that did not examine race or racial discrimination in relation to the causes of homelessness, characteristics, or behaviors of homeless populations, or services designed to help individuals exit homelessness in the United States. Studies were included even if the relationship between race and homelessness or a facet of homelessness (shelter use, service use, service efficacy), was not the central research question. However, studies of homeless populations where race was only listed as one among many covariates to be adjusted for in a regression model, or where samples were stratified by race, but where race was not mentioned in the research question, findings, or discussion of results, were excluded from this analysis. For example, an evaluation of a cervical cancer screening intervention for homeless women in which the population was stratified by race, but in which the analysis focused narrowly on the medical outcome, was excluded from the final sample (Bharel, Santiago, Forgione, Leon, & Weinreb, 2015). This article was excluded although the study population included people who were homeless, from various racial backgrounds, because neither race nor homelessness was analyzed in relation to the study outcome. This stage of review resulted in the exclusion of all but 40 peer-reviewed articles.

The second stage of review involved categorization and in-depth analysis of remaining literature. The articles were classified into quantitative or mixed-methods data analyses (29), qualitative data analyses (7), literature reviews (3), and historical analyses (1). The literature reviews, published in the years 1990–95, were found to be outdated, and the historical analysis was excluded as it only addressed homelessness before the 1980s. The 29 remaining quantitative or mixed methods peer-reviewed articles were categorized according to the type of study population: households at risk for homelessness (4), homeless adults (7), homeless men (3), homeless women (3), homeless youth (5), homeless veterans (5), homeless families (1), and homeless drug users (1). These articles were then analyzed for relevant findings related to race, racial discrimination, and homelessness. Two of these studies included a mere observation of the racial demographics of homelessness: that black persons are largely overrepresented in the U.S. homeless populations (Burt & Cohen, 1989); and that Hispanic persons are underrepresented in the homeless population of El Paso, Texas (Castañeda, Klassen, & Smith, 2014). Findings from the remaining 27 of these studies were more complex, and are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. Each table includes a list of overall findings and a summary of study findings related to each overall finding, with sample size, author(s), and date listed. Additionally, each overall finding is rated for strength of evidence using the scale A = good, B = fair, C = poor, and I = inconclusive. This rating was based on the number of participants in each study and the number of studies replicating findings, and has been previously used in literature review analyses (Himathongkam, Nicogossian, Kloiber, & Ebadirad, 2013). Table 1 includes findings that apply to homeless adults in general, and Table 2 includes findings for homeless subgroups including veterans, women, youth, and intravenous drug users (IDUs).

Table 1.

How Is Race Related to Homelessness? Key Findings

| Overall findings, study findings, authors, dates, and study population(s) | Strength of evidencea |

|---|---|

|

1. Demographic characteristics of homeless adults, including average age, whether ever married, employment status, veteran status, appear to vary by race, but findings are not consistent. White homeless individuals significantly older than black homeless individuals (First et al., 1988 [n = 979]; North & Smith, 1994 [n = 900]; Summerlin, 1995 [n = 145]; 1999 [n = 146]; Summerlin et al., 1993 [n = 171]). White significantly more likely than black homeless men ever to have been married (North & Smith, 1994; First et al., 1988), but less likely to be employed than non-white homeless men (North & Smith, 1994). But First et al. (1988) found white homeless individuals more likely to be employed than black homeless individuals, less likely to be Vietnam veterans. Black homeless individuals less transient (had lived in fewer cities over lifetime) than white homeless individuals; and black homeless men scored higher on measures of self-reported health (First et al., 1988; Summerlin et al., 1993). White less likely than non-white homeless women to be mothers or have custody of children under age 15 (North & Smith, 1994). Non-white homeless women younger, had lived on the streets for shorter time, more often received public assistance than white women; white women more often received funds from friends (Coston, 1992 [n = 200]). |

I |

|

2. Length of homelessness, number of episodes, patterns of shelter use have been found to vary by race, but inconsistently. White homeless individuals homeless for significantly longer than black homeless individuals (First et al., 1988; Summerlin, 1995, 1999; Summerlin et al., 1993); white homeless men experienced more episodes of homelessness than black homeless men (Summerlin, 1995, 1999; Summerlin et al., 1993). Black homeless adults and black and Hispanic families had lower likelihoods of exiting shelter than white homeless adults and families, even after controlling for other factors (Culhane & Kuhn, 1998 [n = 153,092]; Wong, Culhane, & Kuhn (1997) [n = 27,919]). Black individuals had a lower likelihood than other individuals of exiting shelter (Culhane & Kuhn, 1998). |

I |

|

3. Black and Hispanic households appear more likely than other households to live in inadequate, crowded housing, but Hispanic households have been found more likely than black households to “double up” to avoid homelessness. In highly racially segregated U.S. cities, probability of living in inadequate and/or crowded housing was much higher for black than white residents (Carter, 2011 [n = 35,007]). But race is a greater predictor than housing affordability of homelessness (Early, 1998 [n = 1,195 homeless, n = 2,594 housed poor]). Black, Hispanic families both paid disproportionate burden of rent compared to general population; both at greater risk of losing housing than general population, but Hispanic families significantly more likely to “double up” to avoid homelessness; had more ability to do so (Wasson, 1995 [n = 1,655]). But households that included “people of color” (n = 23) found less likely than all-white households to be doubled up (Marin & Vacha, 1994 [n = 470]). |

C |

|

4. Black homeless adults report higher rates of drug abuse, lower rates of alcohol abuse and psychiatric problems; as well as different types of childhood adversity than white homeless adults. White homeless men reported more lifetime substance use disorders, family histories of alcohol abuse than non-white men, who more frequently reported drug abuse histories; white women more often reported non-substance abuse psychiatric problems, family histories of psychiatric problems than nonwhite women (North & Smith, 1994). Black homeless women more likely than white, Hispanic homeless women to report substance abuse treatment in prior 30 days (Teruya et al., 2010 [n = 1,331]). Black homeless veterans had greater problems with drug abuse, fewer problems with alcohol abuse than white veterans; fewer serious psychiatric disorders, more social contacts than white veterans (Leda & Rosenheck, 1995 [n = 263]; Rosenheck, Leda, Frisman, & Gallup, 1997 [n = 381]). White homeless adults more likely than non-white homeless adults to report personal, family problems in childhood; non-white homeless adults more likely to report adverse childhood experiences that included poverty (Koegel, Melamid, & Burnham, 1995 [n = 1,563]). In study of white, black, Hispanic homeless women, white women most likely to report physical abuse as children, while black women most likely to report sexual abuse as children (Teruya et al., 2010). |

C |

A, good; B, fair; C, poor; I, inconclusive. Rating based on the number of study participants in each study, number of studies of geographically and demographically different populations reporting similar findings.

Table 2.

How Is Race Related to Homelessness in Different Subpopulations?

| Overall findings, homeless subgroup, study authors, study populations | Strength of evidencea |

|---|---|

|

1. Arrest and incarceration histories appear to differ by race among homeless veterans, women, and youth, with non-white homeless individuals being more likely than white homeless individuals to report arrest or incarceration histories. Hispanic incarcerated veterans were more likely to be chronically homeless than those in other ethnic groups (Tsai, Rosenheck, Kasprow, & McGuire, 2013 [n = 30,834]). Black homeless, mentally ill veterans had more felony arrests than white homeless, mentally ill veterans (Rosenheck et al., 1997 [n = 381]). Non-white youth more likely than white youth to be arrested for a more serious offense; white females more likely than non-white females to be arrested for a less serious offense (Yoder, Muñoz, Whitbeck, Hoyt, & McMorris, 2005 [n = 602]). White, black homeless women more likely to report histories of incarceration than Hispanic homeless women (Teruya et al., 2010 [n = 1,331]). |

C |

|

2. Self-reported satisfaction with health care has been associated with race in some homeless subgroups, not others. Black homeless patients reported lower satisfaction with health care than white homeless patients (Macnee & McCabe, 2004 [n = 168]). No race-based differences found in expressed needs of women entering treatment for co-occurring disorders (Hohman & Loughran, 2013 [n = 237]). White homeless women more likely than black or Hispanic homeless women to report unmet health care needs (Teruya et al., 2010). |

I |

|

3. Black veterans found to be at greater risk of homelessness than white veterans, to more greatly benefit from caseworkers. For male and female veterans, greatest predictors of homelessness and risk of homelessness were black race, unmarried status (Montgomery, Dichter, Thomasson, Fu, & Roberts, 2015 [n = 1,582,125]). Black veterans were placed in higher quality neighborhoods when provided with caseworkers and vouchers than vouchers alone, while the difference was not significant for white veterans (Patterson, Nochajski, & Wu, 2014 [n = 3,835]). |

C |

|

4. Among homeless youth, exposure to health risks and risk behaviors differ between minority and white groups. Significant differences were found in social networks of black, white homeless youth. For white youth only, having heavy drinking peers was significantly associated with heavy drinking (Wenzel, Hsu, Zhou, & Tucker, 2012 [n = 235]). Black youth, LGBT youth, youth tested for HIV, were more likely to have engaged in "survival sex" than white, heterosexual youth, youth not tested for HIV (Walls & Bell, 2011 [n = 1,625]). Female gender and non-black race/ethnicity were associated with having intercourse without a barrier contraceptive method (Halcón & Lifson, 2004 [n = 203]). Among homeless youth, experiences of perceived discrimination were independently associated with increased emotional distress; foreign-born Hispanic youth reported highest levels of perceived discrimination (Milburn et al., 2010 [n = 254]). |

I |

|

5. Among IDUs, persons who are “on the street homeless” and non-white were found to have the highest rates of HIV. (Smereck and Hockman, 1998 [n = 16,588]) |

C |

A, good; B, fair; C, poor; I, inconclusive. Rating based on the number of study participants in each study, number of studies of geographically and demographically different populations reporting similar findings.

Next, the seven qualitative peer-reviewed articles were read and their findings were analyzed. Two involved micro-analyses of specific phenomena: panhandling and social humiliation in Washington, DC (Lankenau, 1999), and early 1990s gentrification in Atlanta (Gustafson, 2013). While the other five qualitative studies shed light on the relationship between race and homelessness, these two did not, so they were set aside. The remaining five studies were then analyzed in connection to findings from the quantitative and mixed-methods studies. The results of this combined analysis are discussed below.

Results

Analyses of the twenty-seven remaining quantitative/mixed-methods studies and five remaining qualitative studies yielded nine synthetic findings (listed in Tables 1 and 2). First, in six studies, significant demographic differences were found between black and white subgroups of homeless adult study populations. Black homeless adults in these studies tended to be younger, less transient, less often married, and to have experienced fewer and shorter episodes of homelessness than white homeless individuals. Two studies also found black homeless individuals to report better health than white homeless individuals (First, Roth, & Arewa, 1988). Reflecting on likely reasons for these differences with regard to homeless men, Summerlin and colleagues stated, “It is possible that the etiology and continuance of homelessness for black and white men are different” (Summerlin, Privette, & Bundrick, 1993).

Three among these six studies also suggest that problems preceding and accompanying homelessness are different for black versus white women. One study found that non-white homeless women (all but 3 percent of whom were black), were more likely than white homeless women to be mothers, to have children under age 15 in their custody, and to be receiving public assistance (North & Smith, 1994). The authors of this study characterized the problems of white men and women in their study population as primarily “internal”—related to psychopathology or family histories of psychiatric problems—and those of nonwhite men and women as “external”—related to socioeconomic problems. These studies suggest that socioeconomic disadvantage furthered by racial discrimination may be a more important precursor of homelessness for black and other ethnic minority persons; whereas serious mental illness and family problems are more likely to be precursors of homelessness for white individuals.

Carter (2011) attempted to clarify how socioeconomic disadvantage and structural racial discrimination puts black persons in the United States at higher risk of homelessness than white persons. Analyzing census data, he posited that poverty, a widening gap between affordable housing supply and demand, and a combination of housing discrimination and racial residential segregation “push” black persons into homelessness in disproportionate numbers. The concentration of homeless shelters in predominantly black communities within central cities, he suggested, may also “pull people out of inadequate substandard housing into homelessness” (Carter, 2011, p. 34). Carter was not able to prove this push–pull hypothesis, but demonstrated that the probability of living in inadequate and crowded housing was much higher for black than white residents in highly racially segregated U.S. cities, such as Detroit, Chicago, and New York.

Living in inadequate and/or crowded housing has previously been identified as a major risk factor for becoming homeless (National Low Income Housing Coalition, 2005). One study found that black and Hispanic households experience similarly high housing burdens (ordinarily measured by the proportion of income needed to pay rent), but that Hispanic households are more able than black households to “double up”—to combine households or move in with another family when affordable housing is not available (Wasson, 1995). This study found that black households were as willing to “double up” as Hispanic households, but that the option was less available to them. A high school homeless liaison in Chicago interviewed for one of the qualitative studies analyzed here provided anecdotal support for this trend. For “Hispanics, particularly Mexican Americans, doubling up is much more common,” stated the liaison, identified as Ms. Franklin. “It used to be like that in the African American community, but it’s become so fragmented in the last, I would say 30 to 35 years, that that doesn’t happen anymore” (Aviles De Bradley, 2015). This finding, which is summarized in Table 1, item 3, suggests that access to housing may be a more common precursor of homelessness for black households than for white or Hispanic households.

Along with these structural differences, four studies (summarized in Table 1, item 4) indicate that patterns of substance abuse and mental illness among homeless individuals differ by race, with black homeless adults experiencing lower rates of alcohol abuse and psychiatric problems than white homeless adults, but higher rates of drug abuse. Related to this difference is the finding in one study that white homeless adults more often reported personal and family problems in childhood whereas black homeless adults more often reported poverty in childhood (Koegel et al., 1995). In another study of white, black, and Hispanic homeless women, white women were most likely to report physical abuse in childhood, whereas black homeless women were most likely to report sexual abuse. The above findings suggest that substance abuse and mental illness, as well as poverty and other adverse childhood experiences, likely play roles in homelessness for black adults, but that the factors preceding and accompanying homelessness differ by race.

Race, Incarceration, and Homelessness

Four studies in this review indicate that non-white homeless individuals are generally more likely than white homeless individuals to report arrest or incarceration histories, with more complex patterns appearing in women and female youth. This overall racial disparity can easily be explained by the meteoric rise in incarceration for nonviolent drug crimes in the past 35 years (The Sentencing Project, 2015), as well as the facts that black men are six times as likely to be incarcerated as white men (Pew Research Center, 2014) and that most homeless individuals are male. The only surprising aspect of the finding on racial differences in incarceration rates among homeless individuals is the lack of attention to this topic. For example, Koegel et al. (1995) reported that homeless individuals in their study were disproportionately black, disproportionately male, and more likely than the general population to lack a high school diploma and to have histories of incarceration, but the researchers did not analyze the relationships between these factors. One of the qualitative studies in this review, however, did examine reasons for homelessness among formerly incarcerated black men (n = 17), and found that it was linked to both unemployment and “poor or severed family connections,” including “histories of violence with their partners” that prevented them from returning to their former homes (Cooke, 2004, p. 159). These findings suggest that further analysis of structural and interpersonal factors in relation to homelessness among formerly incarcerated populations is warranted.

Study of the relationship between incarceration, race, and homelessness may also provide explanations for existing findings. For example, the findings in two studies (summarized in Table 1, item 2), that black individuals and families were less likely to exit shelter than white individuals and families, might be explained by the higher rates of incarceration among black than white populations, since a felony conviction can disqualify an individual from public housing for several years (New Destiny Housing, 2016).

Race and Health Among Homeless Populations

Four studies summarized in Table 2 suggest that health and safety risks associated with homelessness differ for white and non-white populations, especially for women, although findings are mixed as to how vulnerability to these risks differs by race and gender, and the variety of subpopulations studied render generalizations to the broader homeless population difficult. A study of HIV rates among unsheltered homeless intravenous drug users (IDUs) found that Hispanic male and female IDUs as well as black female IDUs had significantly higher rates of HIV than other IDUs in the study sample, and in comparison to their housed counterparts; whereas HIV infection rates among white IDUs did not differ by housing status (Smereck & Hockman, 1998). In a study of black, white, and Hispanic homeless women in Los Angeles (n = 1,331), Teruya and coworkers found that white women were significantly more likely (57 percent) to report an unmet need for medical care than black (22 percent) or Hispanic (10 percent) women (Teruya et al., 2010). The white women also had the highest rates of alcohol and drug abuse in the prior year; as well as reporting being physically and sexually assaulted as adults, depression, and “bodily pain.” The researchers cited a similar 2009 study which found that white homeless women in Los Angeles (n = 974) had higher rates of hospitalization than homeless Hispanic or black women, and had higher rates of childhood sexual and physical abuse, adult physical abuse, mental health hospitalization, serious medical symptoms, and lack of regular health care than these other groups (Gelberg et al., 2009). These latter findings appear consistent with the research suggesting that psychosocial problems are more likely to be associated with homelessness among white than non-white individuals. These studies also suggest the need for research that examines the complex interactions between race and gender in experiences of homelessness as it pertains to health status.

Race and Veteran Homelessness

For veterans, who have recently become a focus of efforts to prevent and end homelessness (United States Department of Veterans Affairs, 2015), two studies suggest that race matters in these efforts. First, a large-scale study analyzing use of a homelessness screening instrument for more than 1.5 million veterans in VA medical centers across the United States found that black veterans were significantly more likely than others to be at risk of homelessness or to have experienced homelessness (Montgomery et al., 2015). Second, another recent study suggests that case management may be more critical to success in addressing homelessness for black veterans than for white veterans. This study compared outcomes for 145 veterans provided with caseworkers as well as vouchers under the HUD-VASH (Veterans Administration Supportive Housing) program with those in a case-matched comparison group (n = 3,869) of veterans who were only provided with housing vouchers (Patterson, Nochajaski, & Wu, 2014). Black clients in the HUD-VASH caseworker group were significantly more likely to be housed in higher quality neighborhoods than those in the voucher-only group, but this difference in neighborhood quality placement was not significant for white clients. These two studies suggest the need for additional research into the needs of black veterans at risk for homelessness.

Race and Youth Homelessness

The U.S. black population is overrepresented among homeless youth (Bassuk, Murphy, Coupe, Kenney, & Beach, 2011), and race- and gender-based differences similar to those among the adult homeless population have been observed among this group. As Table 2, item 4 indicates, exposure to mental and physical health risks as well as prevalence of high-risk behaviors differ between non-white and white homeless youth. In a study of Los Angeles homeless youths ages 13–24, Wenzel et al. (2012) found that black youth were more connected to networks that included people who regularly attended school, whereas white youth were more connected to networks of people who drank to intoxication and were homeless. For white youth but not black youth, a significant association was found between heavy drinking behavior and connection to peers who drank heavily. In another study, white, female homeless youth were found to engage in significantly higher rates of sex without barrier contraception than non-white and male youth (Halcón & Lifson, 2004). However, Walls and Bell (2011) found that black homeless youth were significantly more likely than white homeless youth to engage in “survival sex” in exchange for drugs, money, clothes, or other items. LGBT youth and those who had been tested for HIV were also more likely than the overall population of homeless youth to engage in survival sex.

A single study has examined racial discrimination in relation to youth homelessness. Milburn and colleagues (2010) found that perceptions of racial/ethnic discrimination were associated with heightened levels of emotional distress among homeless adolescents in Los Angeles, and that foreign-born Hispanic persons in this group reported the highest levels of perceived discrimination. Since a positive identification with one’s racial/ethnic group has been shown to reduce emotional distress for members of minority groups, the authors suggested that mental health programs be designed for these youth to “build upon racial ethnic/identification and pride” (Milburn et al., 2010, p. 66). This study provides evidence that the physical and mental health risks that homeless youth face are related to racial, ethnic, and gender discrimination.

Finally, a qualitative study involving interviews with six black homeless youth in Chicago found that these students did not become homeless by choice (i.e., were not runaways) and emphasized the racialized, class-based, and gendered nature of the institutions these youth encounter during their homelessness (Aviles De Bradley, 2011). This emphasis underlines the overall finding in these studies that this population’s age-related vulnerabilities intersect in complex and still poorly understood ways with racial discrimination, as well as vulnerabilities associated with gender, sexual orientation, and other hierarchical aspects of U.S. society.

Homelessness in Black Versus Hispanic Populations

Studies involving some homeless subpopulations, including IDU, incarcerated men and women, and families in New York City shelters, indicate that Hispanics in these groups face greater health risks in comparison to the general homeless population (Smereck & Hockman, 1998; Tsai et al., 2013; Wong et al., 1997). However, other studies suggest that Hispanics are healthier (Teruya et al., 2010) than other groups experiencing homelessness. Additionally, a few qualitative studies have investigated why Hispanic persons are under-represented in the U.S. homeless population. In an ethnographic study of a placement program for mentally ill, homeless adults in New York, Marcus (2005) found that placements of Hispanic clients with adult family members were more successful than those of black clients. Although all clients received disability payments that helped cover household rent and expenses, Hispanic clients were more likely to be viewed as contributors to the household, whereas black clients were more likely to be resented by family members and to return to a homeless shelter. According to Marcus, this difference occurred because black Americans have adopted American kinship norms, which center on individual autonomy and consumption, while Hispanic Americans adhere to norms common among immigrant communities, in which collective well-being and accumulation is valued over individual autonomy. DeVerteuil (2011) also observed this difference in a study involving interviews with 16 social service agencies for Central Americans in Los Angeles. He found that Central Americans were almost entirely absent from local shelters. Peoples’ strong social networks meant “there was always some friend or family member to take them in” (DeVerteuil, 2011, p. 938). However, these same networks could prevent other community members from thriving due to the obligations they imposed. Given the wide diversity of the Hispanic population, more research is needed to examine how homelessness differs among different Hispanic subgroups.

Discussion

While research on race and homelessness in the United States is limited, sufficient studies have been conducted to conclude that peoples’ pathways into homelessness and experiences of homelessness differ substantially among black, white, and Hispanic populations. As Rosenheck and co-workers have stated (1997, p. 637), one likely explanation for these racially based differences is that “[s]ocial disadvantage and racial discrimination may play an important role in the genesis of black homelessness, while disability and illness are of greater importance among whites.” However, the findings presented above suggest that such an explanation may be too simplistic, given the greater likelihood of drug abuse and incarceration among black persons who are homeless.

Moreover, many of the earlier studies finding race-based patterns of difference within homeless populations were conducted before the publication or dissemination of landmark studies showing that patterns of individual homelessness fall into three distinct categories: chronic (long periods of homelessness accompanied by disability), episodic (repeated brief episodes), and transitional (one brief period). This typology, based on studies that used cluster analysis to examine shelter use data (Kuhn & Culhane, 1998), has been widely adopted by service providers to match homeless individuals and families to appropriate services, including permanent supportive housing (PSH) for chronic cases and temporary “rapid rehousing” assistance for transitional and some episodic cases (NAEH, 2011, 2014). Future studies examining race-based differences in homelessness and homeless services will have to take into account this typology and how it relates to these putative differences.

The studies reviewed here also indicate that gender, veteran status, and other little-studied factors such as sexual orientation appear to influence pathways into and out of homelessness for different populations. These findings suggest a need for research that not only examines the relationship between race and homelessness, but takes into account these other factors and the ways they interact to precipitate homelessness and influence the efficacy of interventions to address it. As families make up an increasing proportion of the U.S. homeless population (HUD, 2014), it will also be important to examine how race, in connection with these other factors, affects families’ vulnerability to homelessness and the success of interventions with families experiencing or at risk of homelessness.

Limitations

This review has several important limitations. It is not a systematic meta-analysis and does not involve rigorous evaluation of the methodologies employed in various studies. Its broad-brush approach leaves room for additional reviews with different aims. Since this review excluded numerous studies in which homelessness and race were mentioned, it may have excluded findings of potential value in informing the design of future research on homeless populations. Another limitation is that this review did not look further back than 1985. More in-depth historical analysis that re-examines widely held assertions about earlier homeless populations being almost exclusively white and male (Bachrach, 1984) may shed additional light on the enduring legacy of racial discrimination in relation to homelessness.

Conclusion

This review highlights current weaknesses in the research on race and homelessness and calls attention to the need for additional research in key areas such as incarceration, race, and homelessness, as well as the ways that race, gender, veteran status, and other demographic factors influence entry to and exit from homelessness. By taking into account the impact of racial discrimination on the individual and structural levels, research can better inform our understanding of how to address and prevent homelessness. Meanwhile, despite the fact that this reviewed research is limited, existing findings are sufficient to suggest that developers of policies and programs to address homelessness need to consider race as one of many socially shaped axes of difference that can influence their ability to effectively serve their target populations. Such policies and programs must be designed in a manner that explicitly addresses both black persons’ general elevated risk for becoming homeless, and the different risk profiles of different subgroups. Such an awareness needs to be integrated into objectives, strategies, training, and design of programs. By doing so, policymakers and program planners can work to remove previously hidden obstacles to success in ending homelessness.

Acknowledgments

This article is based on a presentation given in November 2014 at the George Mason University Forum on Health, Homelessness, and Poverty. The author would like to thank the organizers of this forum for the invitation to participate, and the other participants for their feedback. The author would also like to acknowledge the National Library of Medicine (Grant no. 1G13LM009707-01) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) History Office (DeWitt Stetten Postdoctoral Fellowship) for funding the foundational research that led to this publication. David Cantor of the Office of NIH History and Professor David K. Rosner of Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health inspired and guided this research. Any opinions expressed in this article are solely the author’s and do not reflect the position of the Office of NIH History.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared.

The more general term “black persons” is used here purposely, instead of “African Americans,” as a means to acknowledge that some individuals in the research discussed were likely migrants from Afro-Caribbean nations such as Haiti, Trinidad and Tobago, or Jamaica, or from African nations. Many people from these countries do not self-identify as “African American” (Jones & Erving, 2015). Some research referenced in this article used the category “African American” and other research used the category “black.”

References

- Aviles De Bradley Anne M. Unaccompanied Homeless Youth: Intersections of Homelessness, School Experiences and Educational Policy. Child Youth Services. 2011;32(2):155–72. [Google Scholar]

- Aviles De Bradley Anne M. Homeless Educational Policy: Exploring a Racialized Discourse Through a Critical Race Theory Lens. Urban Education. 2015;50(7):839–69. [Google Scholar]

- Bachrach Leona L. Research on Services for the Homeless Mentally Ill. Hospital and Community Psychiatry. 1984;35(9):910–13. doi: 10.1176/ps.35.9.910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrow Susan, Herman Daniel B, Cordova Pilar, Elmer Streuning. Mortality Among Homeless Shelter Residents in New York City. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89(4):529–34. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.4.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassuk Ellen, Murphy Christina, Coupe Natalie Thompson, Kenney Rachel R, Beach Corey Anne. America’s Youngest Outcasts: 2010. Needham, MA: The National Center on Family Homelessness; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter Ellen, Hopper Kim. Private Lives/Public Spaces: Homeless Adults on the Streets of New York City. New York: ommunity Service Society, Institute for Social Welfare Research; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Bharel Monica, Santiago Emely R, Forgione Sanju Nembang, León Casey K, Weinreb Linda. Eliminating Health Disparities: Innovative Methods to Improve Cervical Cancer Screening in a Medically Underserved Population. American Journal of Public Health. 2015;105(S3):S438–42. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt Martha R, Cohen Barbara E. Differences Among Homeless Single Women, Women with Children, and Single Men. Social Problems. 1989;36(5):508–24. [Google Scholar]

- Carter George R., III From Exclusion to Destitution: Race, Affordable Housing, and Homelessness. Cityscape: A Journal of Policy Development and Research. 2011;13(1):33–70. [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda Ernesto, Klassen John D, Smith Curtis. Hispanic and Non-Hispanic Homeless Populations in El Paso, Texas. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2014;36(4):488–505. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke Cheryl L. Joblessness and Homelessness as Precursors of Health Problems in Formerly Incarcerated African American Men. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2004;36(2):155–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2004.04013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coston Charisse Tia Maria. The Influence of Race in Urban Homeless Females’ Fear of Crime. Justice Quarterly. 1992;9(4):721–29. [Google Scholar]

- Culhane Dennis P, Kuhn Randall. Patterns and Determinants of Public Shelter Utilization Among Homeless Adults in New York City and Philadelphia. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 1998;17(1):23–43. [Google Scholar]

- DeVerteuil Geoffrey. Survive but Not Thrive? Geographical Strategies for Avoiding Absolute Homelessness Among Immigrant Communities. Social & Cultural Geography. 2011;12(8):929–45. [Google Scholar]

- Early Dick W. The Role of Subsidized Housing in Reducing Homelessness: An Empirical Investigation Using Micro-Data. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 1998;17(4):687–96. [Google Scholar]

- Farr Rodger, Koegel Paul, Burnam Audrey. A Study of Homelessness and Mental Illness in the Skid Row Area of Los Angeles. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- First Richard J, Roth Dee, Arewa Bobbie Darden. Homelessness: Understanding the Dimensions of the Problem for Minorities. Social Work. 1988;33(2):120–24. [Google Scholar]

- Frey William H. 100 Largest Metros: Black White Segregation Indices Sorted by 2005-9 Brookings Institution and University of Michigan Social Science Data Analysis Network’s Analysis of 2005-9 American Community Survey and 2000 Census Decennial Data. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Population Studies Center; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gelberg Lillian, Andersen Ronald M, Longshore Douglas, Leake Barbara, Nyamathi Adeline, Teruya Cheryl, Arangua Lisa. Hospitalization Among Homeless Women: Are There Ethnic and Drug Abuse Disparities. Journal of Behavioral Health Services Research. 2009;36(2):212–32. doi: 10.1007/s11414-008-9144-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson Seth. Displacement and the Racial State in Olympic Atlanta 1990–1996. Southeastern Geographer. 2013;53(2):198–213. [Google Scholar]

- Halcón Linda L, Lifson Alan R. Prevalence and Predictors of Sexual Risks Among Homeless Youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2004;33(1):71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Hibbs Jonathan R, Benner Lawrence, Klugman Lawrence, Spencer Robert, Macchia Irene, Mellinger Anne K, Fife Daniel. Mortality in a Cohort of Homeless Adults in Philadelphia. New England Journal of Medicine. 1994;331(5):304–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199408043310506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himathongkam Tinapa, Nicogossian Arnaud, Kloiber Otmar, Ebadirad Nelya. Updates of Secondhand Smoke Exposure on Infants’ and Children’s Health. World Medical & Health Policy. 2013;5(2):124–40. [Google Scholar]

- Hodnicki Donna R. Homelessness. Health-Care Implications. Journal of Community Health Nursing. 1990;7(2):59–67. doi: 10.1207/s15327655jchn0702_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohman Melinda, Loughran Hilda. What Do Female Clients Want from Residential Treatment? The Relationship Between Expressed and Assessed Needs, Psychosocial Characteristics, and Program Outcome. Journal of Dual Diagnosis. 2013;9(1):3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness. Intergenerational Disparities Experienced by Homeless Black Families [Online] 2012 http://www.icphusa.org/filelibrary/ICPH_Homeless%20Black%20Families.pdf Accessed April 5, 2016.

- Jones Marian Moser. Creating a Science of Homelessness During the Reagan Era. Milbank Quarterly. 2015;93(1):139–78. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones Caralee, Erving Christy L. Structural Constraints and Lived Realities: Negotiating Racial and Ethnic Identities for African Caribbeans in the United States. Journal of Black Studies. 2015;46(5):521–46. [Google Scholar]

- Kochanek Kenneth D, Arias Elizabeth, Anderson Robert N. How Did Cause of Death Contribute to Racial Differences in Life Expectancy in the United States in 2010? NCHS Data Brief No. 125. National Center for Health Statistics US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Online] 2013 http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db125.pdf Accessed April 4, 2016. [PubMed]

- Koegel Paul, Melamid Elan, Burnham M Audrey. Childhood Risk Factors for Homelessness Among Homeless Adults. American Journal of Public Health. 1995;85(12):1642–49. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.12.1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogstad Jens Manuel. Hispanics Only Group to See Its Poverty Rate Decline and Incomes Rise. Pew Research Center. 2014 Sep 19; [Online]. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/09/19/hispanics-only-group-to-see-its-poverty-rate-decline-and-incomes-rise/. Accessed April 4, 2016.

- Kuhn Randall, Culhane Dennis P. Applying Cluster Analysis to Test a Typology of Homelessness by Pattern of Shelter Utilization: Results From the Analysis of Administrative Data. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1998;26(2):207–32. doi: 10.1023/a:1022176402357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lankenau Stephen E. Stronger than Dirt: Public Humiliation and Status Enhancement Among Panhandlers. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography. 1999;28(3):288–318. doi: 10.1177/089124199129023451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leda Catherine, Rosenheck Robert. Race in the Treatment of Homeless Mentally Ill Veterans. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1995;183(8):529–37. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199508000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macnee Carol L, McCabe Susan. Satisfaction with Care Among Homeless Patients: Development and Testing of a Measure. Journal of Community Health Nursing. 2004;21(3):167–78. doi: 10.1207/s15327655jchn2103_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus Anthony. Whose Tangle is it Anyway? The African-American Family, Poverty and United States Kinship. The Australian Journal of Anthropology. 2005;16(1):47–61. [Google Scholar]

- Marin Marguerite V, Vacha Edward. Self-Help Strategies and Resources Among People at Risk of Homelessness: Empirical Findings and Social Services Policy. Social Work. 1994;39(6):649–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milburn Norweeta G, Batterham Philip, Ayala George, Rice Eric, Solorio Rosa, Desmond Kate, Lord Lynwood, Iribarren Javier, Rotheram-Borus Mary Jane. Discrimination and Mental Health Problems Among Homeless Minority Young People. Public Health Reports. 2010;125(1):61–67. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery Ann Elizabeth, Dichter Melissa E, Thomasson Arwin M, Fu Xiaoying, Roberts Christopher B. Demographic Characteristics Associated with Homelessness and Risk Among Female and Male Veterans Accessing VHA Outpatient Care. Women’s Health Issues. 2015;25(1):42–48. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Alliance to End Homelessness. The State of Homelessness in America: January 2011. Washington, DC: National Alliance to End Homelessness; 2011. [Online]. http://www.endhomelessness.org/library/entry/state-of-homelessness-in-america-2011. Accessed April 5, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- National Alliance to End Homelessness. The State of Homelessness in America 2012. Washington, DC: National Alliance to End Homelessness; 2012. [Online]. http://www.endhomelessness.org/page//files/4361_file_FINAL_The_State_of_Homelessness_in_America_2012.pdf Accessed April 5, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- National Alliance to End Homelessness. The State of Homelessness in America 2013. Washington, DC: National Alliance to End Homelessness; 2013. [Online]. http://www.endhomelessness.org/page/-/files/SOH%20Chapter%201.pdf Accessed April 5, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- National Alliance to End Homelessness. The State of Homelessness in America 2014. Washington, DC: National Alliance to End Homelessness; 2014. [Online]. http://www.endhomelessness.org/library/entry/the-state-of-homelessness-2014 Accessed April 5, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- National Low Income Housing Coalition. An Initial Estimate of People with Housing Problems from the 2003 American Housing Survey: Research Note #5-01 [Online] 2005 http://nlihc.org/library/other/periodic/Note05-01 Accessed April 4, 2016.

- New Destiny Housing. NYCHA: Criminal Background Ineligibility [Online] 2016 http://www.newdestinyhousing.org/get-help/nycha-criminal-background-ineligibility Accessed April 5, 2016.

- North Carol S, Smith Elizabeth M. Comparison of White and Nonwhite Homeless Men and Women. Social Work. 1994;39(6):639–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell James J. Premature Mortality in Homeless Populations: A Review of the Literature. Nashville, TN: National Health Care for the Homeless Council; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson Kelly L, Nochajski Tom, Wu Laiyun. Neighborhood Outcomes of Formally Homeless Veterans Participating in the HUD-VASH Program. Journal of Community Practice. 2014;22(3):324–41. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. Chart of the Week: The Black-White Gap in Incarceration Rates [Online] 2014 http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/07/18/chart-of-the-week-the-black-white-gap-in-incarceration-rates/ Accessed April 5, 2016.

- Rosenheck Robert, Leda Catherine, Frisman Linda, Gallup Peggy. Homeless Mentally Ill Veterans: Race, Service Use, and Treatment Outcomes. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1997;67(4):632–38. doi: 10.1037/h0080260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth Dee. Homelessness in Ohio: A Study of People in Need: Statewide Report. Columbus: Ohio Department of Mental Health, Office of Program Evaluation and Research; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Smedley Audrey, Smedley Brian D. Race as Biology Is Fiction, Racism as a Social Problem Is Real: Anthropological and Historical Perspectives on The Social Construction of Race. American Psychologist. 2005;60(1):16–26. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smereck Geoffrey AD, Hockman Elaine M. Prevalence of HIV Infection and HIV Risk Behaviors Associated with Living Place: On-the-Street Homeless Drug Users as a Special Target Population for Public Health Intervention. American Journal of Drug & Alcohol Abuse. 1998;24(2):299–319. doi: 10.3109/00952999809001714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summerlin John R. Adaptation to Homelessness: Self-actualization, Loneliness and Depression in Street Homeless Men. Psychological Reports. 1995;77(1):295–314. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1995.77.1.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summerlin John R. Cognitive-Affective Preparation for Homelessness: Quantitative and Qualitative Analyses of Childhood Out-of-home Placement and Child Abuse in a Sample of Homeless Men. Psychological Reports. 1999;85(2):553–73. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1999.85.2.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summerlin John R, Privette Gayle, Bundrick Charles M. Black and White Homeless Men: Differences in Self-Actualization, Willingness to Use Services, History of Being Homeless, and Subjective Health Ratings. Psychological Reports. 1993;72(3):1039–49. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1993.72.3.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teruya Cheryl, Longshore Douglas, Andersen Ronald M, Arangua Lisa, Nyamathi Adeline, Leake Barbara, Gelberg Lillian. Health and Health Care Disparities Among Homeless Women. Women & Health. 2010;50(8):719–36. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2010.532754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Leadership Conference. Today in Civil Rights History. 2009 Jul 2; [Online]. http://www.civilrights.org/archives/2009/07/481-cra.html Accessed April 5 2016.

- The Sentencing Project. Trends in Corrections Fact Sheet: Drug Policy [Online] 2015 http://sentencingproject.org/doc/publications/inc_Trends_in_Corrections_Fact_sheet.pdf Accessed April 5, 2016.

- Tsai Jack, Rosenheck Robert, Kasprow Wesley J, McGuire James F. Risk of Incarceration and Clinical Characteristics of Incarcerated Veterans by Race/Ethnicity. Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2013;48(11):1777–86. doi: 10.1007/s00127-013-0677-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Veterans Affairs. National Center on Homelessness among Veterans [Online] 2015 http://www.endveteranhomelessness.org Accessed December 8, 2015.

- United States Department of Housing and Urban Development. The 2014 Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress Part 1–Point-in-Time Estimates of Homelessness [Online] 2014 https://www.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/2014-AHAR-Part1.pdf Accessed April 5, 2016.

- United States Department of Housing and Urban Development. The 2015 Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress Part 1–Point-in-Time Estimates of Homelessness [Online] 2015 https://www.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/2015-AHAR-Part-1.pdf Accessed April 5, 2016.

- United States Interagency Council on Homelessness. Opening Doors. Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness [Online] 2010 https://www.usich.gov/resources/uploads/asset_library/Opening%20Doors%202010%20FINAL%20FSP%20Prevent%20End%20Homeless.pdf Accessed April 5, 2016.

- United States Interagency Council on Homelessness. Opening Doors. Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness (Update) [Online] 2015 https://www.usich.gov/opening-doors Accessed April 5, 2016.

- Walls N Eugene, Bell Stephanie. Correlates of Engaging in Survival Sex Among Homeless Youth and Young Adults. The Journal of Sex Research. 2011;48(5):423–36. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2010.501916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasson Renya R. Race, Ethnicity and Homelessness. Journal for Peace and Justice Studies. 1995;6(2):19–51. [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel Suzanne L, Hsu Hsun-Ta, Zhou Annie, Tucker Joan S. Are Social Network Correlates of Heavy Drinking Similar Among Black Homeless Youth and White Homeless Youth? Journal of Studies on Alcohol & Drugs. 2012;73(6):885–89. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams David R, Mohammed Selina A. Discrimination and Racial Disparities in Health: Evidence and Needed Research. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;32(1):20–47. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams David R, Neighbors Harold W, Jackson James S. Racial/Ethnic Discrimination and Health: Findings from Community Studies. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(2):200–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong Yin-Ling Irene, Culhane Dennis P, Kuhn Randall. Predictors of Exit and Reentry Among Family Shelter Users in New York City. Social Service Review. 1997;71(3):441–62. [Google Scholar]

- Yoder Kevin A, Muñoz Ed A, Whitbeck Les B, Hoyt Dan R, McMorris Barbara J. Arrests Among Homeless and Runaway Youths: The Effects of Race and Gender. Journal of Crime and Justice. 2005;28(1):35–58. [Google Scholar]