Abstract

Lethal acrodermatitis (LAD) is a genodermatosis with monogenic autosomal recessive inheritance in Bull Terriers and Miniature Bull Terriers. The LAD phenotype is characterized by poor growth, immune deficiency, and skin lesions, especially at the paws. Utilizing a combination of genome wide association study and haplotype analysis, we mapped the LAD locus to a critical interval of ~1.11 Mb on chromosome 14. Whole genome sequencing of an LAD affected dog revealed a splice region variant in the MKLN1 gene that was not present in 191 control genomes (chr14:5,731,405T>G or MKLN1:c.400+3A>C). This variant showed perfect association in a larger combined Bull Terrier/Miniature Bull Terrier cohort of 46 cases and 294 controls. The variant was absent from 462 genetically diverse control dogs of 62 other dog breeds. RT-PCR analysis of skin RNA from an affected and a control dog demonstrated skipping of exon 4 in the MKLN1 transcripts of the LAD affected dog, which leads to a shift in the MKLN1 reading frame. MKLN1 encodes the widely expressed intracellular protein muskelin 1, for which diverse functions in cell adhesion, morphology, spreading, and intracellular transport processes are discussed. While the pathogenesis of LAD remains unclear, our data facilitate genetic testing of Bull Terriers and Miniature Bull Terriers to prevent the unintentional production of LAD affected dogs. This study may provide a starting point to further clarify the elusive physiological role of muskelin 1 in vivo.

Author summary

Lethal acrodermatitis (LAD) is an autosomal recessive hereditary disease in dogs. It is characterized by poor growth, immune deficiency and characteristic skin lesions of the paws and of the face. We mapped the LAD locus to a ~1.11 Mb segment on canine chromosome 14. Whole genome sequence data of an LAD affected dog and 191 controls revealed a candidate causative variant in the MKLN1 gene, encoding muskelin 1. The identified variant, a single nucleotide substitution, MKLN1:c.400+3A>C, altered the 5’-splice site at the beginning of intron 4. We experimentally confirmed that this variant leads to complete skipping of exon 4 in the MKLN1 mRNA in skin. Various cellular functions have been postulated for muskelin 1 including roles in intracellular transport processes, cell morphology, cell spreading, and cell adhesion. Our data from dogs reveal a novel in vivo role for muskelin 1 that is related to the immune system and skin. MKLN1 thus represents a novel candidate gene for human patients with unsolved acrodermatitis and/or immune deficiency phenotypes. LAD affected dogs may serve as models to gain more insights into the function of muskelin 1.

Introduction

Acrodermatitis enteropathica in humans (OMIM #201100) is an inherited disorder of zinc metabolism. Affected patients display an inflammatory rash, diarrhea and a general failure to thrive [1–3]. This disease is caused by variants in the SLC39A4 gene encoding a zinc transporter that mediates the uptake of dietary zinc in the gut. Clinical signs in patients will ameliorate or even resolve upon oral supplementation with zinc [4]. A similar SLC39A4 associated hereditary zinc deficiency exists in cattle [5].

In Bull Terriers, a related phenotype termed lethal acrodermatitis (LAD) has been reported in the scientific literature as early as 1986 [6]. LAD is inherited as a monogenic autosomal recessive trait. Affected puppies show characteristic skin lesions on the feet and on the face, diarrhea, bronchopneumonia, and a failure to thrive. The skin lesions consist of erythema and tightly adherent scales, erosions or ulcerations with crusts involving primarily the feet, distal limbs, elbows, hocks, and muzzle. Later on, hyperkeratosis of the footpads and deformation of the nails occur. LAD affected dogs also show a coat color dilution in pigmented skin areas. An abnormally arched hard palate impacted with decayed, malodorous food is a characteristic clinical marker for the disease (Fig 1) [6–8].

Fig 1. LAD phenotype.

(A) Inflammatory skin lesions in the face of an affected Bull Terrier. (B) Similar lesions in the inguinal region. (C) LAD affected puppy in the middle of two non-affected littermates. A pronounced growth delay and a subtle coat color dilution are visible. (D, E) Fore paws of an LAD affected Bull Terrier puppy at necropsy. Symmetrical scaling and crusting of the skin including interdigital areas and foot pads is visible (F, G) Histopathological micrographs of the junction of interdigital haired skin and digital pad from an affected Bull Terrier puppy (F) and a control dog (G). Marked thickening of the epidermis, excessive layers of non-cornifying epithelium and a large pustule are evident in the affected dog. Hematoxylin-eosin, bar = 400 µm.

LAD dogs are immunodeficient with a reduction in serum IgA levels and frequently suffer from skin infections with Malassezia or Candida [9,10]. LAD manifests clinically in the first weeks of life. Affected puppies typically die before they reach an age of two years, either due to infections such as bronchopneumonia or because they are euthanized when their paw pad lesions become very severe and painful. They grow slower than their non-affected littermates and at the age of one year have about half the body weight and size of an unaffected dog [8]. Some, but not all studies found reduced levels of zinc in the serum of LAD affected dogs [6,8,11]. In contrast to acrodermatitis enteropathica in humans, oral or intravenous supplementation of zinc does not lead to an improvement of the clinical signs in LAD affected dogs [6]. A proteomic analysis reported changes related to inflammatory response in the liver of LAD affected puppies [12].

In the present study, we performed a genome-wide association study (GWAS) followed by a whole genome sequencing approach to unravel the causative genetic variant for LAD in Bull Terriers and Miniature Bull Terriers.

Results

Mapping of the LAD locus

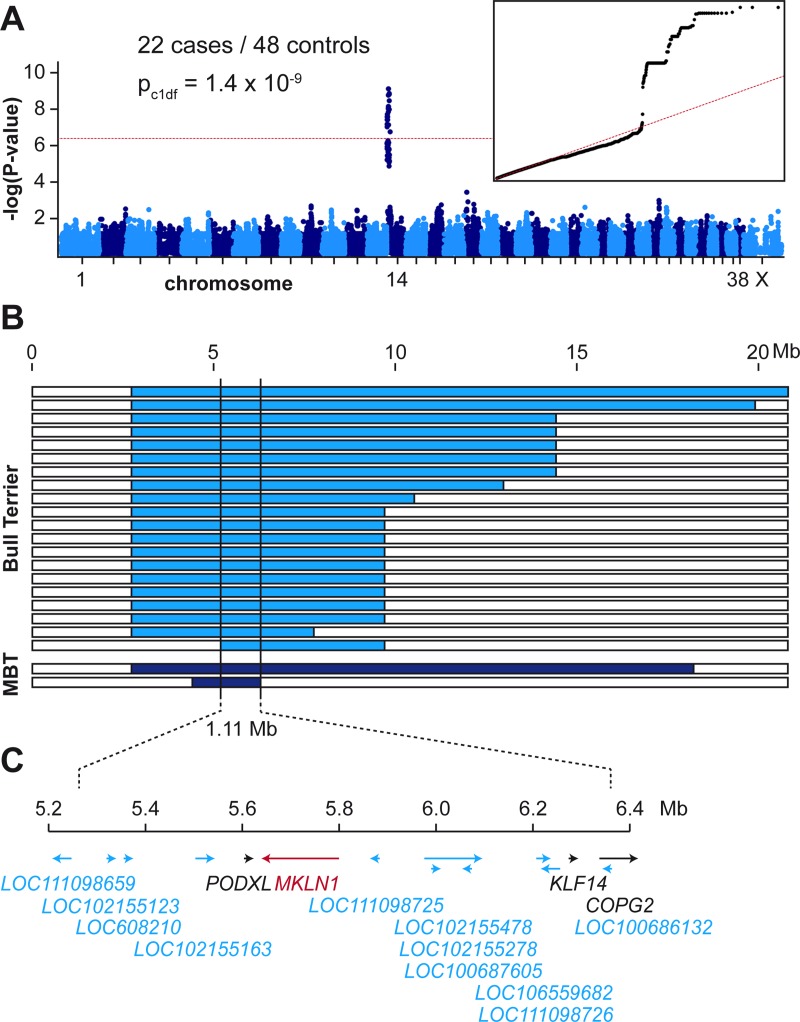

We performed a GWAS with genotypes from 78 Bull Terriers and Miniature Bull Terriers. After quality control, the pruned dataset consisted of 22 LAD cases, 48 controls and 76,419 markers. We obtained a single strong association signal with 57 markers exceeding the Bonferroni-corrected genome-wide significance threshold after adjustment for genomic inflation (PBonf. = 6.5 x 10−7). All significantly associated markers were located on chromosome 14 within an interval spanning from 0.9 Mb– 10.6 Mb. The three top-associated markers all had a P-value of 1.4 x 10−9 and were located between 5.2 Mb– 5.9 Mb on chromosome 14 (Fig 2).

Fig 2. Mapping of the LAD locus.

(A) A GWAS was performed in a cohort of 22 LAD cases and 48 controls. The Manhattan plot shows a single significant signal at the beginning of chromosome 14. The red line indicates the Bonferroni significance threshold (PBonf = 6.5 x 10-7). The quantile-quantile (QQ) plot in the inset shows the observed versus expected–log(p) values. The straight red line in the QQ plot indicates the distribution of p-values under the null hypothesis. The deviation of p-values at the right side indicates that these markers are stronger associated with the trait than it would be expected by chance. (B) Haplotype analysis in the 22 LAD cases. Each horizontal bar represents the chromosome 14 haplotypes of one dog. Twenty Bull Terriers and two Miniature Bull Terriers (MBT) had large homozygous intervals with allele sharing on chromosome 14 indicated in blue. The homozygous haplotype segment shared between all 22 dogs spanned ~1.11 Mb. The critical interval for the causative LAD variant corresponded to the interval between the first flanking heterozygous markers on either side or chr14:5,248,244–6,355,383 (CanFam 3.1 assembly). (C) Gene annotation for the critical interval. The NCBI annotation release 105 listed 4 protein coding genes (indicated in black or red) and 11 genes for non-coding RNAs (indicated in blue).

To narrow down the identified region, we visually inspected the genotypes of the cases to perform autozygosity mapping. We searched for homozygous regions with allele sharing and found one region of ~1.11 Mb, which was shared between all 22 cases. The critical interval for the causative LAD variant corresponded to the interval between the first flanking heterozygous markers on either side or chr14:5,248,244–6,355,383 (CanFam 3.1 assembly).

Identification of a candidate causative variant

We sequenced the genome of an affected Bull Terrier at 24x coverage and called single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and small indel variants with respect to the reference genome (CanFam 3.1). We then compared these variants to whole genome sequence data of 3 wolves and 188 control dogs from genetically diverse breeds. This analysis identified five private homozygous variants in the critical interval in the affected dog (Table 1, S1 Table).

Table 1. Variants detected by whole genome re-sequencing of an LAD affected dog.

| Filtering stepa | Number of variants |

|---|---|

| Homozygous variants in the whole genome | 3,061,192 |

| Homozygous variants in the 1.11 Mb critical interval on chromosome 14 | 1,445 |

| Private homozygous variants (absent from 191 control genomes) in critical interval | 5 |

a The sequences were compared to the reference genome (CanFam 3.1) from a Boxer.

Four of these five variants were intergenic and classified as “modifier” by the SNPeff software. The remaining fifth variant was located within the 5’-splice site of intron 4 of the MKLN1 gene and its SNPeff impact prediction was “low”. The formal designation of this variant is chr14:5,731,405T>G or MKLN1:c.400+3A>C (S1 Fig).

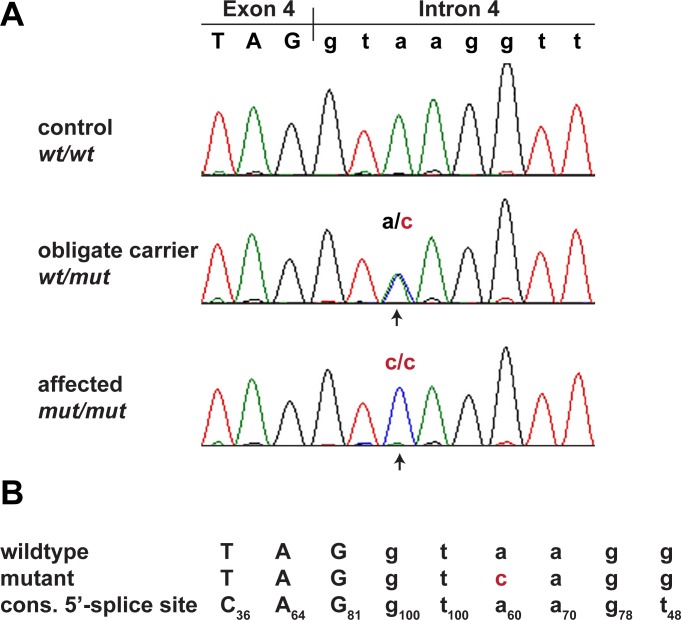

We confirmed the presence of this variant by Sanger sequencing (Fig 3). As MKLN1:c.400+3A>C represented the only plausible candidate causative variant, we genotyped 251 Bull Terriers, 89 Miniature Bull Terriers, and 462 dogs from 62 other breeds for this variant (Table 2). The variant showed perfect association with the LAD phenotype in Bull Terriers and Miniature Bull Terriers (PFisher = 4.8 x 10−58). All 46 available cases were homozygous for the variant, whereas the unaffected dogs were either homozygous wildtype or heterozygous. The test dogs included a subset of unaffected Bull Terriers and Miniature Bull Terriers from Finland, which were not specifically collected for this study and therefore considered representative for the general population. The 166 Finnish dogs contained 37 heterozygous dogs (22%). The variant was not found in any of the tested dogs from other breeds.

Fig 3. Sanger confirmation of the MKLN1:c.400+3A>C variant.

(A) Electropherograms from dogs with the three different genotypes. (B) Wildtype and mutant allele compared to the consensus sequence for the human U2 GT-AG type 5’-splice sites [13]. Subscript numbers in the consensus sequence indicate the percentage of the respective conserved nucleotide in 183,682 investigated human 5’-splice site motifs of the U2 GT-AG type. The additional difference to the optimal consensus in the U1 spliceosomal RNA recognition site in the mutant allele is highlighted in red. In human 5’-splice sites the most frequent base at position 3 is an A (60%). G is also common at this position (35%), while C and T are both rare (<3%) [13].

Table 2. Association of the MKLN1:c.400+3A>C genotype with the LAD phenotype.

| MKLN1:c.400+3A>C genotype | A/A | A/C | C/C |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cases, Bull Terrier (n = 41) | - | - | 41 |

| Cases, Miniature Bull Terrier (n = 5) | - | - | 5 |

| Controls, Bull Terrier (n = 210) | 132 | 78 | - |

| Controls, Miniature Bull Terrier (n = 84) | 59 | 25 | - |

| Controls, other breeds (n = 462) | 462 | - | - |

Functional confirmation

To assess the putative impact of the MKLN1 variant on splicing, we analyzed the frequency of the wildtype and mutant sequence motifs in a compilation of 186,630 human 5’-splice sites [13,14]. The canine wildtype sequence TAGgtaagg was identical to the sequence of 276 human 5’-splice sites, while the mutant sequence motif TAGgtcagg occurred in only 3 human 5’-splice sites. The very low frequency of the mutant sequence motif suggested that MKLN1:c.400+3A>C might affect the efficacy of the splicing process. Several other pathogenic A>C transversions at 5’-splice sites’ position +3 with subsequent exon skipping have been described in the literature [15–17].

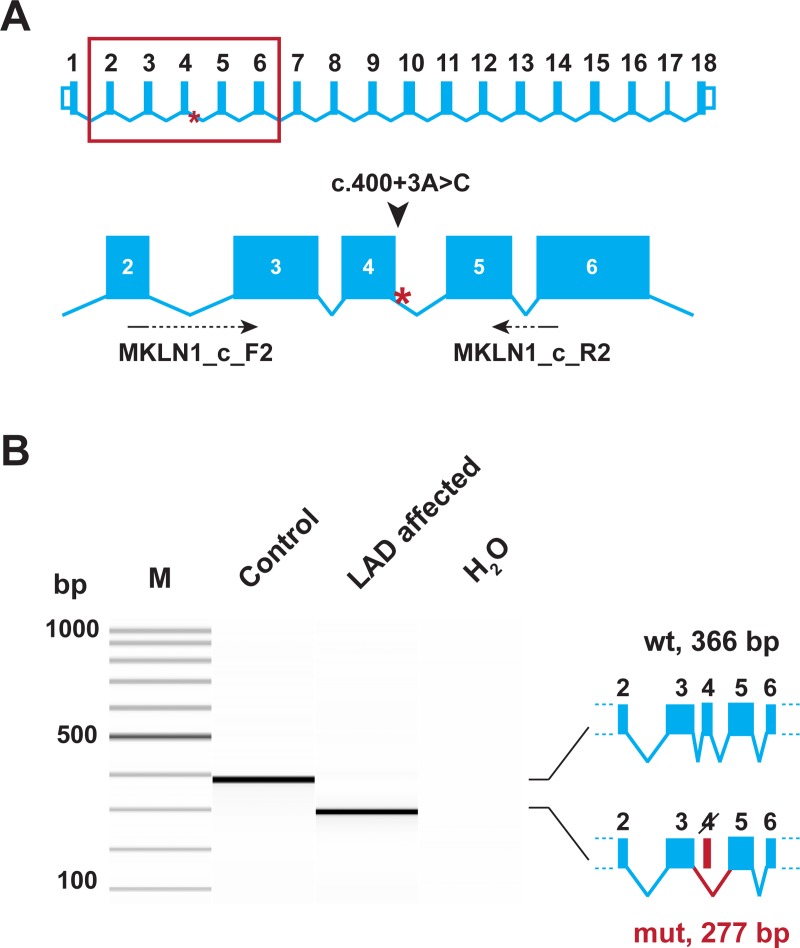

We experimentally analyzed MKLN1 transcripts in skin RNA from an LAD affected dog with the homozygous mutant C/C genotype in comparison to a healthy control dog (A/A genotype). RT-PCR with primers located at the exon 2/3 and exon 5/6 boundaries yielded a cDNA fragment of the expected size in the control dog, but not in the LAD affected dog. In the LAD affected dog, a very clean cDNA amplicon lacking exon 4 was obtained. This experiment demonstrated a complete skipping of exon 4 in MKLN1 transcripts as consequence of the genomic MKLN1:c.400+3A>C variant (r.312_400del89; Fig 4). If translated, the mutant transcript was predicted to result in a severely truncated protein containing only the first 105 of a total of 735 amino acids of the wildtype protein (p.(Gly105SerfsTer10); S2 Fig).

Fig 4. Experimental verification of the MKLN1 splice defect.

(A) The genomic organization of the MKLN1 gene. Exons 2–6 are enlarged and the position of the primers used for RT-PCR is indicated. (B) RT-PCR was performed using skin cDNA from a control and an LAD affected Bull Terrier. The picture shows a Fragment Analyzer gel image of the experiment. In the control animal, only the expected 366 bp product is visible. In the LAD affected dog, a 277 bp product representing a transcript lacking exon 4 is visible. The identity of the bands was verified by Sanger sequencing. Thus, the MKLN1:c.400+3A>C variant leads to complete skipping of exon 4 (MKLN1:r.312_400del89).

Discussion

In the present study we identified a splice defect in the canine MKLN1 gene in Bull Terriers with LAD. The combination of GWAS and haplotype analysis localized the causative variant to a relatively small chromosomal region with only a few characterized genes including MKLN1. The splice region variant in MKLN1 was the only plausible variant within this critical interval that showed the expected genotype concordance with the LAD phenotype in a large cohort of more than 300 Bull Terriers and ~500 dogs from other breeds.

The identified MKLN1:c.400+3A>C variant resulted in exon 4 skipping and a frameshift as 89 nucleotides were missing from the mutant transcripts. It therefore seems likely that mutant transcripts are degraded by nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Considering the strong genetic association of the variant with the phenotype and the fact that we demonstrated a functional defect on the MKLN1 transcript level, we think that our data strongly suggest the causality of the MKLN1:c.400+3A>C variant for LAD in Bull Terriers and Miniature Bull Terriers.

MKLN1 encodes the widely expressed intracellular protein muskelin 1, also known as TWA2. The function of muskelin 1 is only partially understood. It was originally described as a protein that mediates adhesive and cell-spreading responses to thrombospondin 1, an extracellular matrix adhesion molecule [18]. However, different studies suggested that the function of muskelin 1 goes beyond this pathway and are also supported by the fact that muskelin 1, which has homologs in invertebrates and even fission yeast, evolved earlier than the vertebrate-specific thrombospondin 1 [19,20]. Muskelin 1 is a multidomain protein with an N-terminal discoidin domain, a LisH / CTLH tandem domain, and six C-terminal Kelch repeats, which forms homotetramers [21]. The LisH domain was shown to be crucial for muskelin 1 dimerization and cytoplasmic localization, and, together with the head-to-tail interaction via the discoidin domain, also for the tetramerization of muskelin 1 [20,21].

Consistent with its multidomain structure and ubiquitous expression, diverse binding partners have been reported for muskelin 1. It binds prostaglandin EP3 receptor isoform α [22] and heme-oxidase 1, which counteracts inflammatory and reactive oxygen species induced damage [23]. It is part of the CTLH complex, the homolog of yeast E3 ubiquitin ligase, where it binds to RanBPM and Twa I [24–26] and interacts with the cardiogenic transcription factor TBX-20 [27]. In the rat lens, muskelin 1 is a substrate of Cdk5 and interacts with the Cdk5 activator p39 [28]. Also in lens, it was shown that p39 links muskelin 1 to myosin II and stress fibers [29].

Mkln1-/- knockout mice are viable and do not have skin lesions comparable to those in Bull Terriers with LAD. However, they exhibit a subtle coat color dilution phenotype similar to that seen in LAD affected dogs. In these Mkln1-/- knockout mice, muskelin 1 was identified as a protein required for GABAA receptor endocytosis and trafficking in neurons via direct interaction with the α1 subunit of GABAA receptors and the motor proteins dynein and myosin VI. The dilute coat color of Mkln1-/- knockout mice suggested that muskelin is a trafficking factor involved in several different intracellular transport processes, possibly including melanosome transport [30].

The lacking skin lesions in Mkln1-/- knockout mice raise the questions whether muskelin 1 depletion does not result in disease in mice; whether their clinical signs would only manifest at a (much) older age; or whether the sterile environment of the laboratory animals prevented infections and thus the development of skin lesions. In the latter case, LAD would be a primary immunodeficiency disorder, in agreement with the observation of lower IgA levels and higher susceptibility to microbial infection in LAD affected dogs [8–10, 12]. Given the diverse known protein-protein interactions of muskelin 1, it is however likely that absence of muskelin 1 leads to dysfunctions beyond the immune system.

In humans, an intronic SNV in MKLN1 was associated with urinary potassium excretion in Korean adults and another intronic MKLN1 SNV with early bipolar disorder [31,32]. Furthermore, MKLN1 has been associated with asthma in independent GWASs. A SNV in MKLN1 ranked among the top 100 SNVs associated with childhood asthma in a study sample of 429 affected-offspring trios from a European American population [33]. A different SNV in the 5’-UTR of MKLN1 was associated with asthma in a population including patients with severe or difficult-to-treat asthma [34].

In the ExAC database, only one MKLN1 missense, but no nonsense, frameshift or splice site variants present in a homozygous state were found [35,36]. Furthermore, the probability of loss of function (LoF, specified as nonsense, splice acceptor, and splice donor variants) tolerance was estimated to be 1.00, indicating that the MKLN1 gene is extremely LoF intolerant [37]. Therefore, it is conceivable that loss of function variants on both alleles might lead to severe phenotypes in humans.

To our knowledge, no link between muskelin 1 and zinc or copper metabolism has been reported to date. While acrodermatitis enteropatica in humans and acrodermatitis in cattle clinically resemble LAD in dogs, these diseases may be caused by completely different molecular mechanisms. The fact that findings on zinc levels in the few published studies on LAD affected dogs were contradictory and zinc supplementation did not lead to improvement of lesions [6] support this hypothesis.

In conclusion, we identified the MKLN1:c.400+3A>C variant leading to a splice defect in the MKLN1 gene as candidate causative variant for LAD in Bull Terriers and Miniature Bull Terriers. The molecular pathogenesis of LAD remains unclear. Our data facilitate genetic testing of Bull Terriers and Miniature Bull Terriers to prevent the unintentional breeding of LAD affected dogs. LAD affected dogs may serve as models to further clarify the elusive physiological role of muskelin 1 in vivo.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

All animal experiments were performed according to the local regulations. The dogs in this study were examined with the consent of their owners. The study was approved by the “Cantonal Committee For Animal Experiments” (Canton of Bern; permits 22/07, 23/10, and 75/16).

Animals and samples

Bull Terriers with their characteristic egg-shaped head were founded as a dog breed in the 1850s in the United Kingdom. Originally, there were no size standards in this breed and smaller dogs were bred as a variety of the regular Bull Terrier. Eventually, two sub-populations formed and the Miniature Bull Terrier with a maximum height of 35.5 cm was recognized as an independent breed in 1991 by the American Kennel Club (AKC) and in 2011 by the European Fédération Cynologique Internationale (FCI). Therefore, Bull Terriers and Miniature Bull Terriers share a common ancestral gene pool, but represent independent closed populations today.

This study included samples from 251 Bull Terriers (41 LAD cases / 210 controls) and 89 Miniature Bull Terriers (5 LAD cases / 84 controls). Case/controls status was based on owners’ reports. We additionally used 462 dogs from 62 breeds, which were assumed to be free of the disease allele (S3 Table). Skin biopsies were taken from two LAD affected Bull Terriers from toe, nose, lip, and forearm and fixed in 10% buffered formalin for 24 hours. Biopsies were processed, embedded in paraffin and sectioned at 4 µm. Skin sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The histopathology was performed by veterinary pathologists (BR, Dipl.-ECVP, and SH). Two further biopsies from comparable sites of the same dogs were submerged in RNAlater solution for subsequent RNA isolation.

DNA isolation and SNV genotyping

We isolated genomic DNA from EDTA blood samples. Seventy-eight dogs were genotyped for either 173,662 or 218,256 SNVs on the illumina canine_HD chip. The raw SNV genotypes are available at https://www.animalgenome.org/repository/pub/BERN2017.1208/.

GWAS

The initial dataset consisted of 78 dogs and 220,853 markers. Using Plink version 1.9 [38] we excluded markers that were not located on autosomes or the X chromosome (n = 2,327) and markers with a genotyping rate lower than 90% (n = 49,814). Using the R package GenABEL [39] and the command “check.markers”, dogs with a call rate < 90% (n = 3), ibs > 95% (n = 0), high individual heterozygosity (FDR = 0.01) (n = 1, included in dogs with low call rate) as well as markers with a maf < 1% (n = 55,931) and a genotyping rate < 90% (n = 10,951) were excluded. Five outliers in the multidimensional scaling plot based on a genomic distance matrix were also removed. In a second quality control step, markers deviating from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (FDR = 0.2) in controls (n = 1,239), markers with a genotyping rate < 90% (n = 0) and maf < 1% (n = 26,215) were excluded, resulting in a final dataset of 70 dogs (22 cases, 48 controls) and 76,419 markers. A polygenic model of the hglm package [40], with a kinship matrix based on autosomal markers in the cleaned dataset as random effect, was estimated and a score test for association using the function “mmscore” was performed. The genomic inflation factor was 1.16. We corrected for multiple testing using Bonferroni correction with a significance level of 0.05. QQ plots were created using qqman version 0.1.4 [41].

Haplotype analysis

We visually inspected plink tped files for the region of interest on chromosome 14 using Excel and searched for homozygous regions with haplotype sharing in cases with a call rate >90%. The first flanking heterozygous markers on either side of the homozygous region in 22 cases defined the borders of the critical interval.

Whole genome sequencing of an affected Bull Terrier

An Illumina PCR-free TruSeq fragment library with 350 bp insert size of an LAD affected Bull Terrier was prepared. We collected 219 million 2 x 150 bp paired-end reads or 24x coverage on a HiSeq3000 instrument. The reads were mapped to the dog reference genome assembly CanFam3.1 and aligned using Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA) version 0.7.5a [42] with default settings. The generated SAM file was converted to a BAM file and the reads were sorted by coordinate using samtools [43]. Picard tools (http://sourceforge.net/projects/picard/) was used to mark PCR duplicates. To perform local realignments and to produce a cleaned BAM file, we used the Genome Analysis Tool Kit (GATK version 2.4.9, 50) [44]. GATK was also used for base quality recalibration with canine dbsnp version 139 data as training set. The sequence data were deposited under the study accession PRJEB16012 and sample accession SAMEA4504844 at the European Nucleotide Archive.

Variant calling

Putative SNVs were identified in each of 192 samples (S2 Table) individually using GATK HaplotypeCaller in gVCF mode [45]. Subsequently all sample gVCF files were joined using Broad GenotypeGVCFs walker (-stand_emit_conf 20.0; -stand_call_conf 30.0). Filtering was performed using the variant filtration module of GATK using the following standard filters: SNVs: Quality by Depth: QD < 2.0; Mapping quality: MQ < 40.0; Strand filter: FS > 60.0; MappingQualityRankSum: MQRankSum < -12.5; ReadPosRankSum < -8.0. INDELs: Quality by Depth: QD < 2.0; Strand filter: FS > 200.0. The functional effects of the called variants were predicted using SnpEFF software [46] together with the NCBI annotation release 104 on CanFam 3.1. For the filtering of candidate causative variants in the case, we used 191 control genomes, which were either publicly available [47] or produced during other projects of our group or contributed by members of the Dog Biomedical Variant Database Consortium. A detailed list of these control genomes is given in S2 Table.

Gene analysis

We used the dog CanFam 3.1 reference genome assembly for all analyses. Numbering within the canine MKLN1 gene corresponds to the accessions XM_005628367.3 (mRNA) and XP_005628424.1 (protein). Numbering within the human MKLN1 gene corresponds to the accessions NM_013255.4 (mRNA) and NP_037387.2 (protein).

Sanger sequencing

We used Sanger sequencing to confirm the candidate variant MKLN1:c.400+3A>C and to genotype the dogs in this study. A 797 bp fragment containing the variant was PCR amplified from genomic DNA using AmpliTaq Gold 360 Master Mix (Life Technologies) and the primers CCATGCACTGTAGCCACATC and TGGAAAAGGTTCCACTTGAAAT. After treatment with shrimp alkaline phosphatase and endonuclease I, PCR products were directly sequenced on an ABI 3730 capillary sequencer (Life Technologies). We analyzed the Sanger sequence data using the software Sequencher 5.1 (GeneCodes).

RNA isolation and RT-PCR

RNA was extracted from skin samples using the RNeasy Fibrous Tissue Mini Kit (Qiagen). The tissue was first finely crushed by mechanical means using TissueLyser (Quiagen), and RNA was extracted by centrifugation following the instructions by the manufacturer. Total mRNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using the SuperScript IV Reverse Transcriptase kit (Thermo Fisher) with oligo d(T) primers. A PCR on the synthesized cDNA was carried out using primer MKLN1_c_F2, CCTCCCCAGTACTTGATTCTG, located at the boundary of exons 2 and 3, and primer MKLN1_c_R2, TTCCTGTTCACGGTACTTGC, located at the boundary of exons 5 and 6 of the MKLN1 gene. The products were analyzed on a Fragment Analyzer capillary gel electrophoresis instrument (Advanced Analytical). The sequence of the obtained RT-PCR products was confirmed by Sanger sequencing as described above.

Supporting information

(PDF)

(PDF)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the dog owners who donated samples and shared pedigree data and phenotype information of their dogs. Sample collections were supported through various programs. French samples were collected by a network of veterinarians and Laetitia Lagoutte and Nadine Botherel managing the Cani-DNA biobank (http://dog-genetics.genouest.org), which is part of the CRB-Anim infrastructure (ANR-11-INBS-0003, in the framework of the "Investing for the Future" program (PIA)). We thank Nathalie Besuchet Schmutz, Muriel Fragnière, Kaisu Hiltunen, Fabiana Jakob, and Sabrina Schenk for expert technical assistance, the Next Generation Sequencing Platform of the University of Bern for performing the high-throughput sequencing experiments, and the Interfaculty Bioinformatics Unit of the University of Bern for providing high performance computing infrastructure. We thank the Dog Biomedical Variant Database Consortium (Gus Aguirre, Catherine André, Danika Bannasch, Doreen Becker, Cord Drögemüller, Oliver Forman, Eva Furrow, Urs Giger, Christophe Hitte, Marjo Hytönen, Vidhya Jagannathan, Tosso Leeb, Hannes Lohi, Cathryn Mellersh, Jim Mickelson, Anita Oberbauer, Jeffrey Schoenebeck, Sheila Schmutz, Claire Wade) for sharing whole genome sequencing data from control dogs. We also acknowledge all canine researchers who deposited dog whole genome sequencing data into public databases.

Data Availability

The Illumina canine HD array SNV genotypes are available at https://www.animalgenome.org/repository/pub/BERN2017.1208/. The whole genome sequences are available at the European Nuclotide Archive. S2 Table lists accessions of all 192 genomes used for the study. All other relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

Parts of this work were funded by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation (CRSII3_160738/1; www.snf.ch) and Albert-Heim Foundation (project no. 105; http://www.albert-heim-stiftung.ch) to TL; starting grant 260997 from the European Research Council (https://erc.europa.eu/) and a grant from the Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation (http://jaes.fi/en/) to HL; grant ANR-11-INBS-0003 from the Agence de la Recherche (http://www.agence-nationale-recherche.fr) to CA; grant OD 010939 from the National Institutes of Health (https://www.nih.gov/) and ACORN grant #01746A from the American Kennel Club Canine Health Foundation (http://www.akcchf.org/) to MLC. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Moynahan EJ (1974) Acrodermatitis enteropathica: a lethal inherited human zinc-deficiency disorder. Lancet 2: 399–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moynahan EJ (1982) The Lancet: Acrodermatitis Enteropathica: A Lethal Inherited Human Zinc-Deficiency Disorder. Nutr Rev 40: 84–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lakdawala N, Grant-Kels JM (2015) Acrodermatitis enteropathica and other nutritional diseases of the folds (intertriginous areas). Clin Dermatol 33: 414–419. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2015.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Küry S, Dréno B, Bézieau S, Giraudet S, Kharfi M, Kamoun R, et al. (2002) Identification of SLC39A4, a gene involved in acrodermatitis enteropathica. Nat Genet 31: 239–240. doi: 10.1038/ng913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yuzbasiyan-Gurkan V, Bartlett E (2006) Identification of a unique splice site variant in SLC39A4 in bovine hereditary zinc deficiency, lethal trait A46: An animal model of acrodermatitis enteropathica. Genomics 88: 521–526. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2006.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jezyk PF, Haskins ME, MacKay-Smith WE, Patterson DF (1986) Lethal acrodermatitis in bull terriers. J Am Vet Med Assoc 188: 833–839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McEwan NA (1990) Lethal acrodermatitis of bull terriers. Vet Rec 127: 95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McEwan NA, McNeil PE, Thompson H, McCandlish IA (2000) Diagnostic features, confirmation and disease progression in 28 cases of lethal acrodermatitis of bull terriers. J Small Anim Pract 41: 501–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McEwan NA (2001) Malassezia and Candida infections in bull terriers with lethal acrodermatitis. J Small Anim Pract 42: 291–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McEwan NA, Huang HP, Mellor DJ (2003) Immunoglobulin levels in Bull terriers suffering from lethal acrodermatitis. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 96: 235–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uchida Y, Moon-Fanelli AA, Dodman NH, Clegg MS, Keen CL (1997) Serum concentrations of zinc and copper in bull terriers with lethal acrodermatitis and tail-chasing behavior. Am J Vet Res 58: 808–810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grider A, Mouat MF, Mauldin EA, Casal ML (2007) Analysis of the liver soluble proteome from bull terriers affected with inherited lethal acrodermatitis. Mol Genet Metab 92: 249–257. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2007.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sheth N, Roca X, Hastings ML, Roeder T, Krainer AR, Sachidanandam R (2006) Comprehensive splice-site analysis using comparative genomics. Nucl Acids Res 34: 3955–3967. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ravi Lab SpliceRack, Motif Frequency, available from: http://katahdin.mssm.edu/splice/viewsplicemotifgraphform.cgi?database = spliceNew

- 15.Martoni E, Urciuolo A, Sabatelli P, Fabris M, Bovolenta M, Neri M, et al. (2009) Identification and characterization of novel collagen VI non-canonical splicing mutations causing Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy. Hum Mutat 30: E662–E672. doi: 10.1002/humu.21022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawarai T, Montecchiani C, Miyamoto R, Gaudiello F, Caltagirone C, Izumi Y, et al. (2017) Spastic paraplegia type 4: A novel SPAST splice site donor mutation and expansion of the phenotype variability. J Neurol Sci 380: 92–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2017.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koppolu AA, Madej-Pilarczyk A, Rydzanicz M, Kosińska J, Gasperowicz P, Dorszewska J, et al. (2017) A novel de novo COL6A1 mutation emphasizes the role of intron 14 donor splice site defects as a cause of moderate-progressive form of ColVI myopathy - a case report and review of the genotype-phenotype correlation. Folia Neuropathol 55: 214–220. doi: 10.5114/fn.2017.70486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adams JC, Seed B, Lawler J (1998) Muskelin, a novel intracellular mediator of cell adhesive and cytoskeletal responses to thrombospondin-1. EMBO 17: 4964–4974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Francis O, Han F, Adams JC (2013) Molecular phylogeny of a RING E3 ubiquitin ligase, conserved in eukaryotic cells and dominated by homologous components, the muskelin/RanBPM/CTLH complex. PLoS One 8: e75217 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prag S, Collett GDM, Adams JC (2004) Molecular analysis of muskelin identifies a conserved discoidin-like domain that contributes to protein self-association. Biochem J 381: 547–559. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Delto CF, Heisler FF, Kuper J, Sander B, Kneussel M, Schindelin H (2015) The LisH motif of muskelin is crucial for oligomerization and governs intracellular localization. Structure 23: 364–373. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2014.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hasegawa H, Katoh H, Fujita H, Mori K, Negishi M (2000) Receptor isoform-specific interaction of prostaglandin EP3 receptor with muskelin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 276: 350–354. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gueron G, Giudice J, Valacco P, Paez A, Elguero B, Toscani M, et al. (2014) Heme-oxygenase-1 implications in cell morphology and the adhesive behavior of prostate cancer cells. Oncotarget 5: 4087–4102. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Umeda M, Nishitani H, Nishimoto T (2003). A novel nuclear protein, Twa1, and Muskelin comprise a complex with RanBPM. Gene 303: 47–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kobayashi N, Yang J, Ueda A, Suzuki T, Tomaru K, Takeno M, et al. (2007) RanBPM, Muskelin, p48EMLP, p44CTLH, and the armadillo-repeat proteins ARMC8α and ARMC8β are components of the CTLH complex. Gene 396: 236–247. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.02.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Valiyaveettil M, Bentley AA, Gursahaney P, Hussien R, Chakravarti R, Kureishy N, et al. (2008) Novel role of the muskelin-RanBP9 complex as a nucleocytoplasmic mediator of cell morphology regulation. J Cell Biol 182: 727–739. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200801133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Debenedittis P, Harmelink C, Chen Y, Wang Q, Jiao K (2011) Characterization of the novel interaction between muskelin and TBX20, a critical cardiogenic transcription factor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 409: 338–343. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.05.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ledee DR, Gao CY, Seth R, Fariss RN, Tripathi BK, Zelenka PS (2005) A specific interaction between muskelin and the cyclin-dependent kinase 5 activator p39 promotes peripheral localization of muskelin. J Biol Chem 280: 21376–21383. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501215200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tripathi BK, Lowy DR, Zelenka PS (2015) The Cdk5 activator P39 specifically links muskelin to myosin II and regulates stress fiber formation and actin organization in lens. Exp Cell Res 330: 186–198. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2014.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heisler FF, Loebrich S, Pechmann Y, Maier N, Zivkovic AR, Tokito M, et al. (2011) Muskelin regulates actin filament- and microtubule-based GABA(A) receptor transport in neurons. Neuron 70: 66–81. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park YM, Kwock CK, Kim K, Kim J, Yang YJ (2017) Interaction between single nucleotide polymorphism and urinary sodium, potassium, and sodium-potassium ratio on the risk of hypertension in Korean adults. Nutrients 9: E235 doi: 10.3390/nu9030235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nassan M, Li Q, Croarkin PE, Chen W, Colby CL, Veldic M, et al. (2017) A genome wide association study suggests the association of muskelin with early onset bipolar disorder: Implications for a GABAergic epileptogenic neurogenesis model. J Affect Disord 208: 120–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.09.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ding L, Abebe T, Beyene J, Wilke RA, Goldberg A, Woo JG, et al. (2013) Rank-based genome-wide analysis reveals the association of Ryanodine receptor-2 gene variants with childhood asthma among human populations. Hum Genomics 7: 16 doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-7-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li X, Howard TD, Zheng SL, Haselkorn T, Peters SP, Meyers DA, et al. (2010) Genome-wide association study of asthma identifies RAD50-IL13 and HLA-DR/DQ regions. J Allergy Clin Immunol 125: 328–335.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.11.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karczewski KJ, Weisburd B, Thomas B, Solomonson M, Ruderfer DM, Kavanagh D, et al. (2017) The ExAC browser: displaying reference data information from over 60 000 exomes. Nucleic Acids Res 45: D840–D845. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.ExAC Browser (Beta), Exome Aggregation Consortium, available from http://exac.broadinstitute.org/

- 37.Lek M, Karczewski KJ, Minikel EV, Samocha KE, Banks E, Fennell T, et al. (2016) Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature 536: 285–291. doi: 10.1038/nature19057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, et al. (2007) PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet 81: 559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aulchenko YS, Ripke S, Isaacs A, van Duijn CM (2007) GenABEL: an R library for genome-wide association analysis. Bioinformatics 23: 1294–1296. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ronnegard L, Shen X, Alam M (2010) hglm: A package for fitting hierarchical generalized linear models. The R Journal 2: 20–28. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Turner S (2017) qqman: Q-Q and Manhattan Plots for GWAS Data. R package version 0.1.4. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package = qqman

- 42.Li H, Durbin R (2009) Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25: 1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li H (2011) A statistical framework for SNP calling, mutation discovery, association mapping and population genetical parameter estimation from sequencing data. Bioinformatics 27: 2987–2993. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, Sivachenko A, Cibulskis K, Kernytsky A, et al. (2010) The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res 20: 1297–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Van der Auwera GA, Carneiro MO, Hartl C, Poplin R, Del Angel G, Levy-Moonshine A, et al. (2013) From FastQ data to high confidence variant calls: the Genome Analysis Toolkit best practices pipeline. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics 43: 110.1–33. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi1110s43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cingolani P, Platts A, Wang le L, Coon M, Nguyen T, Wang L, et al. (2012) A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly 6: 80–92. doi: 10.4161/fly.19695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bai B, Zhao WM, Tang BX, Wang YQ, Wang L, Zhang Z, et al. (2015) DoGSD: the dog and wolf genome SNP database. Nucleic Acids Res 43 (Database issue): D777–783. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF)

(PDF)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

Data Availability Statement

The Illumina canine HD array SNV genotypes are available at https://www.animalgenome.org/repository/pub/BERN2017.1208/. The whole genome sequences are available at the European Nuclotide Archive. S2 Table lists accessions of all 192 genomes used for the study. All other relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.