Abstract

Biological soil crusts (biocrusts) cover about 12% of the Earth’s land masses, thereby providing ecosystem services and affecting biogeochemical fluxes on a global scale. They comprise photoautotrophic cyanobacteria, algae, lichens and mosses, which grow together with heterotrophic microorganisms, forming a model system to study facilitative interactions and assembly principles in natural communities. Biocrusts can be classified into cyanobacteria-, lichen-, and bryophyte-dominated types, which reflect stages of ecological succession. In this study, we examined whether these categories include a shift in heterotrophic communities and whether this may be linked to altered physiological properties. We analyzed the microbial community composition by means of qPCR and high-throughput amplicon sequencing and utilized flux measurements to investigate their physiological properties. Our results revealed that once 16S and 18S rRNA gene copy numbers increase, fungi become more predominant and alpha diversity increases with progressing succession. Bacterial communities differed significantly between biocrust types with a shift from more generalized to specialized organisms along succession. CO2 gas exchange measurements revealed large respiration rates of late successional crusts being significantly higher than those of initial biocrusts, and different successional stages showed distinct NO and HONO emission patterns. Thus, our study suggests that the photoautotrophic organisms facilitate specific microbial communities, which themselves strongly influence the overall physiological properties of biocrusts and hence local to global nutrient cycles.

Introduction

In dryland regions, where vascular vegetation is usually quite sparse, the uppermost millimeters of the soil develop biological soil crusts (biocrusts), which comprise bryophytes, algae, fungi (including lichens), and bacteria (including cyanobacteria) in varying proportions [1, 2]. Multicellular organisms in these communities are poikilohydric [3, 4], being rapidly reactivated once water is available [5]. These characteristics allow them to outlast periods of drought and colonize extreme environments [6].

According to the dominating photoautotrophic organism, biocrusts are classified into cyanobacteria-, lichen-, and moss-dominated types [1, 7, 8]. These types generally reflect different successional stages [9], with the course and speed of succession being influenced by climate, soil and the preceding disturbance event [10–14]. During the early stages of biocrust formation, when cyanobacteria are few in number, heterotrophic diazotrophs may contribute to N2-fixation [15]. Under favorable environmental conditions cyanobacteria-dominated biocrusts may develop into lichen- and bryophyte-dominated biocrusts [2]. It is well known that facilitation plays a major role in community succession [16, 17]. Early stages in the succession of biocrusts can suffer from nutrient limitations or flourish from supplementary nutrients, which may kick-start the process of development [17–19].

Biocrusts have been demonstrated to play a central role in many dryland ecosystem processes, as they form the zone of nutrient accumulation and transformation [2]. By photosynthetic uptake of atmospheric CO2 and fixation of atmospheric N2 [20], biocrusts serve as elemental sinks in the environment. These nutrients serve as food source for plants, animals and other organisms in often strongly depleted dryland ecosystems [21–23]. The contributions of biocrusts to carbon and nitrogen cycles may be significant, as cryptogamic ground covers, including biocrusts, take up 590 Tg a−1 of carbon in steppes and deserts, while the biological nitrogen fixation adds up to 25.7 Tg a−1 of nitrogen [22]. Biocrusts are known to affect soil carbon cycling, as Castillo-Monroy et al. [24] found that 42% of the annual soil respiration of a dryland ecosystem was attributable to biocrust-dominated areas. In Kalahari soils, CO2 effluxes resulted from cyanobacteria and heterotrophic microorganisms in the below-crust soil, which were activated by rainfall [25, 26]. The amount of carbon mineralized and hence the quantity of CO2 emissions is also dependent on the amount of available carbon [27–32]. Thus, the question arises if an alteration of the microbial community will affect the respiration rate and physiological properties of different types of biocrusts.

Most studies are focused on the interaction between a few pairs of species, and neither the complexity of natural communities, such as biocrusts, nor the potential roles of biotic interactions as drivers of ecosystem functioning are being considered [33]. The objective of this study was to investigate the relevance of the dominating photoautotrophic organisms for the overall biocrust microbial composition. We hypothesize that the photoautotrophic organisms affect the composition of the heterotrophic microbial community, thus also the physiological properties of different biocrust types. To study these issues, we analyzed the microbial composition depending on surface cover type, i.e., bare soil and different biocrust types by means of qPCR and high-throughput 16S rRNA gene and fungal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region sequencing. Secondly, we assessed the physiological response of different biocrust types to varying temperature conditions by conducting CO2 gas exchange measurements and investigated the effects of nitrogen cycling on their gaseous reactive N emissions during wetting and drying cycles.

Material and methods

Sampling area

Samples were collected near the village Soebatsfontein next to BIOTA observatory No. 22, in the Northern Cape Province, South Africa. The area is located within the Succulent Karoo biome known for its unique flora of succulent plants, high plant diversity and biocrust cover [34, 35].

Sampling and storage

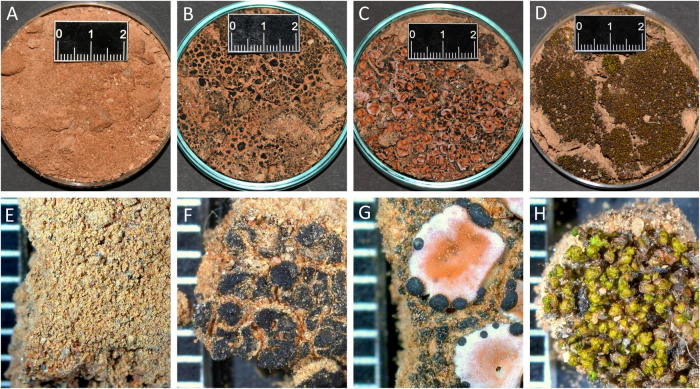

Moss-dominated biocrusts comprised Ceradoton purpureus (Hedw.) Brid [8] (Fig. 1d, h). Lichen-dominated types were characterized by the chlorolichen Psora decipiens (Hedwig) Hoffm. (Fig. 1c, g). Cyanobacteria-dominated biocrusts contained the genera Chroococcidiopsis, Pseudoanabaena, Phormidium, Leptolyngbya, Microcoleus, and Nostoc, sometimes growing together with lichens of the species Collema coccophorum Tuck. [1, 36] (Fig. 1b, f). Bare soil samples (Fig. 1a, e) used for physiological and pH-measurements mainly occurred in spots after recent disturbance. The detailed collection procedure is described in the Supplementary Methods.

Fig. 1.

Different types of biocrusts. (a–d) Present the different biocrust types and bare soil in an overview (scale = 2 cm), (e–h) present close-up views of the respective biocrust types and bare soil, taken with a stereomicroscope (scale = 7 mm). (a, e) Bare soil; (b, f) cyanobacteria-dominated biocrust plus cyanolichens with Collema coccophorum Tuck. as dominating species; (c, g) chlorolichen-dominated biocrust with Psora decipiens (Hedwig) Hoffm. as dominating species; (d, h) moss-dominated biocrust with Ceratodon purpureus (Hedw.) Brid as dominating species

DNA extraction, 16S rRNA gene PCR amplification and sequencing

The biocrust samples were separated into two fractions using a sterile laboratory spatula, i.e., dominating photoautotrophic organisms and the remaining biocrust, and only the second fraction was used for DNA extraction. Homogenization was performed with liquid N2 using a mortar and pestle [37]. DNA extraction was done with the PowerSoil® DNA Isolation Kit (MO BIO, Carlsbad, California) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. An incubation step at 70 °C for 7 min was included, followed by 2 × 1 min of bead beating. Additionally, a negative extraction control reaction was performed. 16S sequence-based amplicon generation, indexing and sequencing of amplicon libraries on a MiSeq platform (Illumina, Eindhoven, Netherlands) with v3 600 cycles chemistry was performed as described in Kozich et al. [38].

The raw NGS data have been deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive at EMBL-EBI (Study accession number PRJEB22584). Merged paired-end data, 2,971,627 reads from 28 samples, were quality-trimmed, leaving 2,608,992 sequences. After removal of mitochondria, chloroplast and control sample sequences 2,454,673 remained (min: 48,009, max: 124,674). For further details, also on quantitative PCR analyses and fungal ITS amplification, refer to the description in the Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Table S1.

Biomass and soil parameters

After measurements, the samples were dried in an oven at 60 °C and the dry weight was gravimetrically determined. Surface area was determined by means of image analysis of digital photos of the samples using the free software ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Chlorophyll was extracted according to the method established by Ronen & Galun [39] using DMSO (Dimethylsulfoxide). The total nitrogen and carbon content was determined by CHN analysis (Elementar Vario Micro Cube, 2016 Elementar Analysensysteme GmbH, Hanau, Germany). pH values of each biocrust type and bare soil (n = 4) were analyzed electrometrically [40]. A detailed description of the biomass and soil parameter determination can be found in the Supplementary Methods.

CO2 gas exchange measurements

Before measurements, the samples were unfrozen and acclimated for at least two days to be fully reactivated again. During that time, they were kept in a climate chamber at 17–22 °C and 50–100 µmol PPFD m−2 s−1 (photosynthetic photon flux density) under a light-dark regime of 14:10 h (moss-dominated crusts) and 12:12 h (cyanobacteria- and lichen-dominated crusts). Once a day, the samples were sprayed with distilled water. These conditions have been shown to be well suited for acclimation of freezer-stored biocrust samples [8, 41].

CO2 gas exchange measurements of three replicates of each biocrust type were performed with a portable photosynthesis system (GFS 3000, Walz GmbH, Effeltrich, Germany) under controlled laboratory conditions. Combined light and water response curves were measured at seven different temperatures (7–37 °C). For that, the samples were wetted until complete saturation and light cycles (0–1500 µmol PPFD m−2 s−1) were repeated until full dehydration. The samples were weighed before and after each light cycle to determine the water content. At the beginning and the end of each measurement period, a water curve at 17 °C was performed to verify the stability of the net photosynthesis (NP) rates of each replicate. Samples of chlorolichen- and cyanobacteria-dominated biocrusts were physiologically stable throughout the measurement period, whereas those of moss-dominated biocrusts were corrected for a decline of physiological properties (see [8]). After measurement of the complete biocrusts, the samples were separated into the dominating photoautotrophic organisms and the heterotrophic biocrust part. Subsequently, CO2 gas exchange measurements were repeated using the photoautotrophic compounds of cyanobacteria- and chlorolichen-dominated biocrusts, for moss-dominated biocrusts the remaining biocrust without moss stems was analyzed [8].

Dynamic chamber measurements

Nitrous acid (HONO) and nitric oxide (NO) emissions of biocrusts were measured with a laboratory dynamic chamber system, described in detail by Wu et al. [42] and Weber et al. [43]. To characterize emissions of different types of biocrusts, samples were wetted with distilled water to water-holding capacity and placed in a ~47 L Teflon chamber, which was located in a temperature controlled cabinet (T = 25 °C). The chamber was continuously flushed with purified gas without HONO, NOx, O3, CxHy and H2O at a flow rate of 8 L min−1. HONO, NOx, O3, CO2 and H2O concentrations in the headspace were monitored during drying of the samples. NO and NO2 were measured with a gas chemiluminescence detector (Model 42 C, Thermo Electron Corporation, USA; limit of detection (LOD) ~120 ppt), whereas HONO emissions were detected with a long path absorption photometer (LOPAP; QUMA Elektronik & Analytik GmbH, Wuppertal, Germany; LOD ~ 5 ppt). Fluxes of the reactive nitrogen gases were calculated based on the surface area of the samples, inlet and outlet gas concentrations and flushing flow rate.

Results

Abundance and diversity

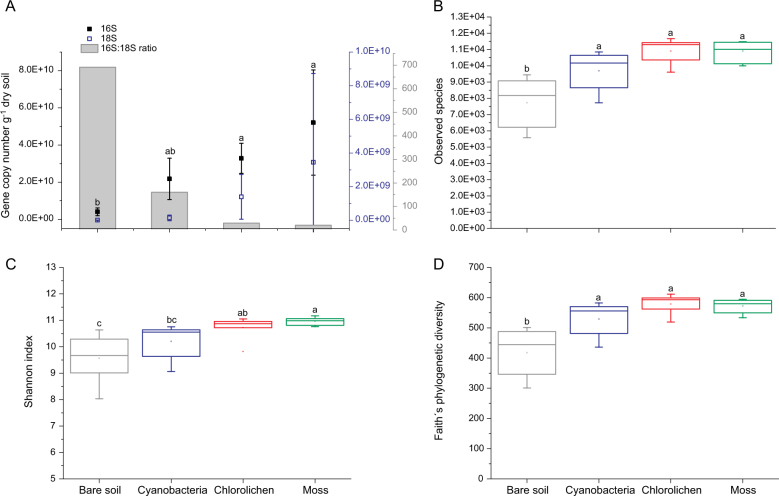

The bacterial and fungal gene copy numbers were highest in moss-dominated biocrusts (Fig. 2a). There was a statistically significant difference in bacterial and fungal gene copy numbers between the different soil/biocrust types (Kruskal–Wallis H test; x2(3) = 19.12, P = 0.0003 and x2(3) = 18.60, P = 0.0003, respectively). The abundance of bacteria and fungi in bare soil was significantly lower than in chlorolichen- and moss-dominated biocrusts. (Nemenyi post hoc test, Fig. 2a). The ratio of bacterial and fungal gene copy numbers decreased with succession.

Fig. 2.

Abundance and diversity of bacteria and fungi in different types of biocrusts and bare soil. Quantitative real time PCR estimates of bacterial and fungal abundance and its ratio in bare soil and biocrusts (a). Comparison of alpha diversity of cyanobacteria-, chlorolichen-, and moss-dominated biocrusts and bare soil; Observed species (b), Shannon diversity index (c), and Faith’s phylogenetic diversity index (d). Based on amplicon 16 S rRNA gene data; rarefaction with a depth of 48 009 reads per sample. Boxes limit the 25th- and 7th-percentile with the median presented as line and mean values marked as point inside. Error bars present the 1st- and 99th-percentile and outliers are shown as dots below and above. Significant differences (P < 0.05) are marked by different letters

Alpha diversity values increased with the succession, regardless of sequencing depth and diversity measure used (Fig. 2b–d, Supplementary Figure S1). Observed species numbers (i.e. number of OTUs) ranged between 5 586.3 and 11 668.7 and differed significantly depending on soil/biocrust type (F (3, 24) = 14.48, P = 1.36×10−5). Post hoc comparison identified bare soil to have significantly lower bacterial diversity compared to biocrusts (Fig. 2b). The Shannon index of species diversity ranged between 8.0 and 11.2, increasing in a stepwise manner from bare soil along succession. It varied significantly depending on crust type (Kruskal–Wallis H test; x2(3) = 18.77, P = 0.0003; Fig. 2c) with a significantly higher value for moss- as compared to cyanobacteria-dominated biocrusts and bare soil. Also phylogenetic diversity values differed significantly as a function of surface cover type (F(3,24) = 15.77, P = 7.05×10−6) with significantly higher phylogenetic diversity values of biocrusts as compared to soil samples not covered by crust (Fig. 2d).

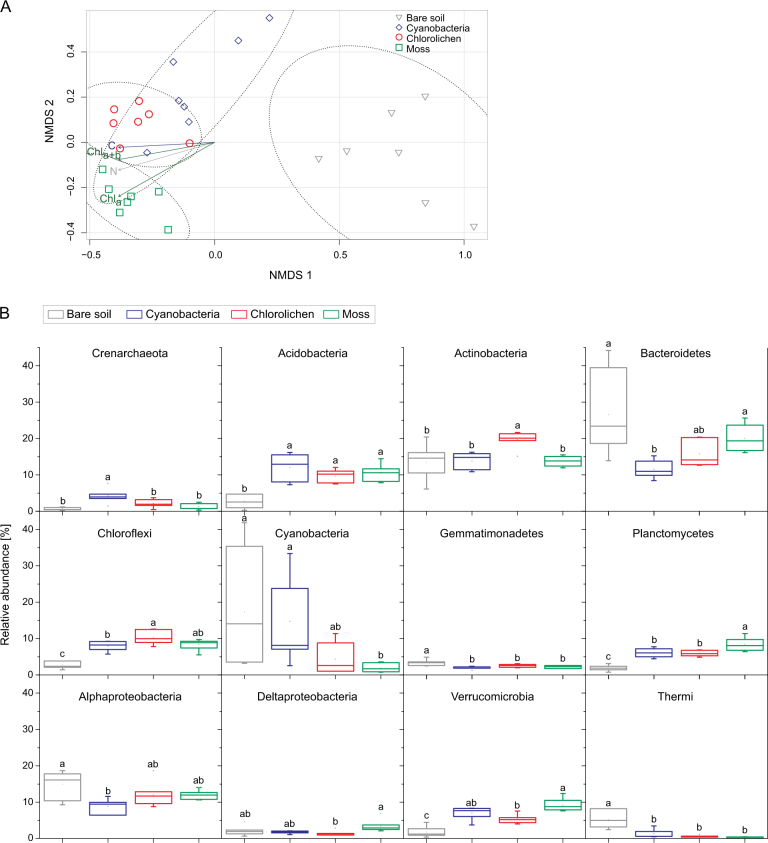

The samples of biocrust types and bare soil formed clearly delimited groups using OTU-based metrics (Bray–Curtis dissimilarity; Fig. 3a) and also clustered separately when community differences were measured using phylogenetic metrics. Whereas samples of bare soil plotted separately and at some distance, samples of cyanobacteria-dominated crusts overlapped with those of chlorolichen- and moss-dominated crust samples, retracing the development from cyanobacteria- towards moss-dominated biocrusts. Soil/biocrust type was a good predictor of community composition based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarity (ANOSIM R = 0.76, P < 0.001). Furthermore, the divergence in community composition measured by phylogenetic metrics was associated with surface cover type (ANOSIM analyses of unweighted UniFrac distances R = 0.82, P < 0.001, ANOSIM of weighted UniFrac R = 0.56, P < 0.001).

Fig. 3.

Dissimilarity of bacterial community composition in bare soil as compared to different biocrust types. Ordination using Non-Metric Multidimensional Scaling derived from Bray–Curtis dissimilarity; based on amplicon 16S rRNA gene data, rarefaction with a depth of 48 009 reads per sample; symbols coded by category. 95% confidence ellipses are shown. The function envfit from the R vegan package was used to fit environmental vectors onto the ordination (a). Relative abundance of bacterial and archaeal taxa in crust habitats and bare soil. Based on amplicon 16S rRNA gene data; rarefaction with a depth of 48 009 reads per sample. Boxes limit the 25th- and 75th percentile with the median presented as line and mean values marked as point inside. Error bars present the 1st and 99th percentile and outliers are shown as dots below and above. Significant differences (P < 0.05) are marked by different letters. n = 7 per category (b)

The development from cyanobacteria- towards moss-dominated biocrusts can partly be seen in fungal community composition (Supplementary figure 2A). Samples of bare soil plotted separately, samples of cyanobacteria-dominated crusts overlapped with those of moss-dominated crust samples (Bray–Curtis dissimilarity; ANOSIM R = 0.66, P < 0.001).

The correlations between soil parameters and NMDS axes of Fig. 3a and S2A are listed in Supplementary Table S2.

Microbial composition

Across all samples, the most abundant phyla were Bacteroidetes (average: 18.5% across all samples), Proteobacteria (15.8%), and Actinobacteria (15.2%), with smaller contributions of Cyanobacteria (9.5%), Acidobacteria (8.7%), Chloroflexi (7.3%), Verrucomicrobia (5.8%) and Planctomycetes (5.6%). Furthermore, the phyla Gemmatimonadetes, Thermi and Armatimonadetes were present. At class level, Alphaproteobacteria (11.9%), Saprospirae (9.2%), Cytophagia (7.6%), Actinobacteria (5.5%), Chloracidobacteria (5.5%), Oscillatoriophycideae (5.9%) and Spartobacteria (5.3%) mainly contributed to the bacterial community. The Alphaproteobacteria were primarily represented by the order Sphingomonadales (4.7%) and Rhizobiales (3.9%) and the class Saprospirae by the order Saprospirales (9.2%). Among the Cytophagia, the order Cytophagales (7.6%) was predominantly detected.

Comparing the samples of the four soil/biocrust types, significant taxonomic differences were observed between all of them (Table 1). We also observed statistically significant differences in the relative abundance between the soil/biocrust types for all bacterial phyla (relative abundance >1%) as well as for Crenarchaeota, (ANOVA, P < 0.01; Fig. 3b; Supplementary Table S3). The relative abundance of Acidobacteria, Chloroflexi, Planctomycetes and Verrucomicrobia was significantly higher in biocrusts compared to bare soil, whereas the relative abundance of Gemmatimonadetes and Thermi was significantly higher in the bare soil as compared to biocrusts.

Table 1.

Comparison of the bacterial taxonomic composition at phylum level across the four categories: cyanobacteria-, chlorolichen-, moss-dominated biocrust associated soil and bare soil

| Bare | Moss | Cyanobacteria | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chlorolichen | U B | P < 0.00001 P < 0.00001 | P < 0.00001 P < 0.00005 | P < 0.00001 P < 0.00001 |

| Cyanobacteria | U B | P < 0.00027 P < 0.0016 | P < 0.00001 P < 0.00001 | |

| Moss | U B | P < 0.00001 P < 0.00001 |

Unadjusted (U) and Bonferroni (B)-adjusted p values for all pairwise comparisons between chlorolichen, cyanobacteria, moss, and bare soil samples. This suggests that all four sample sets are statistically different at phylum level (Generalized Wald-type test statistic; taxa composition data analysis approach introduced by La Rosa et al. (2012)) [79]

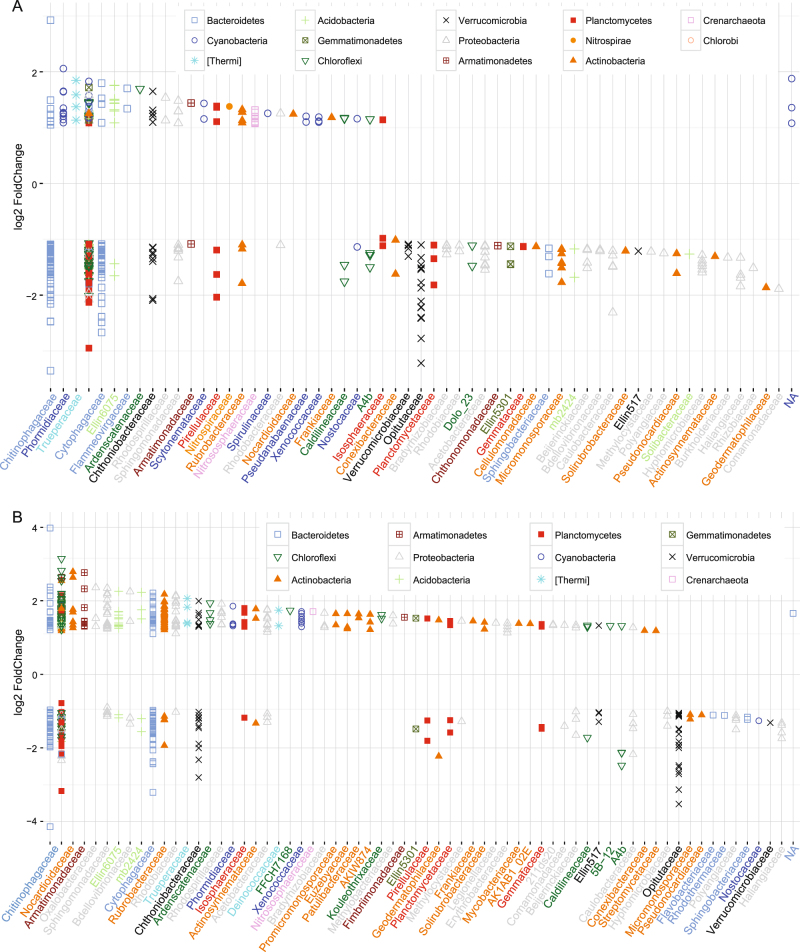

Also on OTU-level, we observed significant differences between surface cover types. Comparing bare soil bacterial communities with those of biocrusts, the number of OTUs that were differentially abundant increased with succession (737/1699/1647; DESeq2, Benjamini–Hochberg-adjusted P value < 0.01, n = 7). The relative abundance of OTUs in bare soil showed most similarities to cyanobacteria-dominated biocrusts, but OTUs related to 17 taxa also had higher relative abundances in the cyanobacteria-dominated biocrusts compared to bare soil. Microbial communities of chlorolichen- and moss-dominated biocrusts were less similar to bare soil, even if these still shared fractions. OTUs related to 32 taxa in chlorolichen- and 27 in moss-dominated crusts were significantly more abundant in biocrusts than in bare soil.

Largest changes were observed for OTUs related to the family Phormidiaceae in cyanobacteria-dominated biocrusts compared to bare soil, and for Chitinophagaceae (Bacteroidetes) in chlorolichen- and moss-dominated biocrusts compared to bare soil. A notable decrease in relative abundance was observed for OTUs classified as Sporichthyaceae, Euzebyaceae, Geodermatophilaceae, Micrococcaceae (Actinobacteria), Flavobacteriaceae, Flammeovirgaceae, Rhodothermaceae (Bacteroidetes), Erythrobacteraceae, Rhodobacteraceae (Alphaproteobacteria), Comamonadaceae (Betaproteobacteria), Bacteriovoracaceae (Deltaproteobacteria), Pseudanabaenaceae (Cyanobacteria), Bacillaceae, Planococcaceae (Firmicutes) and, Trueperaceae (Thermi) for all biocrust types compared to bare soil (Supplementary Figure S3).

Cyanobacteria-dominated biocrusts had a significantly increased relative abundance of OTUs related to the family Phormidiaceae and Trueperaceae compared to moss-covered soil, whereas both Chitinophagaceae and Cytophagaceae had a reduced relative abundance in cyanobacteria-dominated biocrusts (DESeq2, Benjamini–Hochberg-adjusted P value <0.01, n = 7, Fig. 4a). Nocardioidaceae, Armatiomonadaceae and Oxalobacteraceae were elevated in chlorolichen- compared to moss-dominated biocrusts (DESeq2, Benjamini–Hochberg-adjusted P value < 0.01, n = 7, Fig. 4b). A notable decrease in relative abundance was observed for OTUs classified as Lecanorales and Pleosporales for cyanobacteria-, chlorolichen- and moss-dominated biocrusts compared to bare soil. (Supplementary Figure S2B–D).

Fig. 4.

Relative abundance of bacterial OTUs at family-level in cyanobacteria-dominated (a) and chlorolichen-dominated (b) compared to moss-dominated biocrusts. Each symbol represents an OTU and is colored according to phylum. The family level is plotted on the x-axis. Data shown as log2 Fold Change, positive values indicate an increased presence in cyanobacteria-/chlorolichen-dominated as compared to moss-dominated biocrusts (DESeq2, Benjamini–Hochberg adjusted P < 0.01, n = 7)

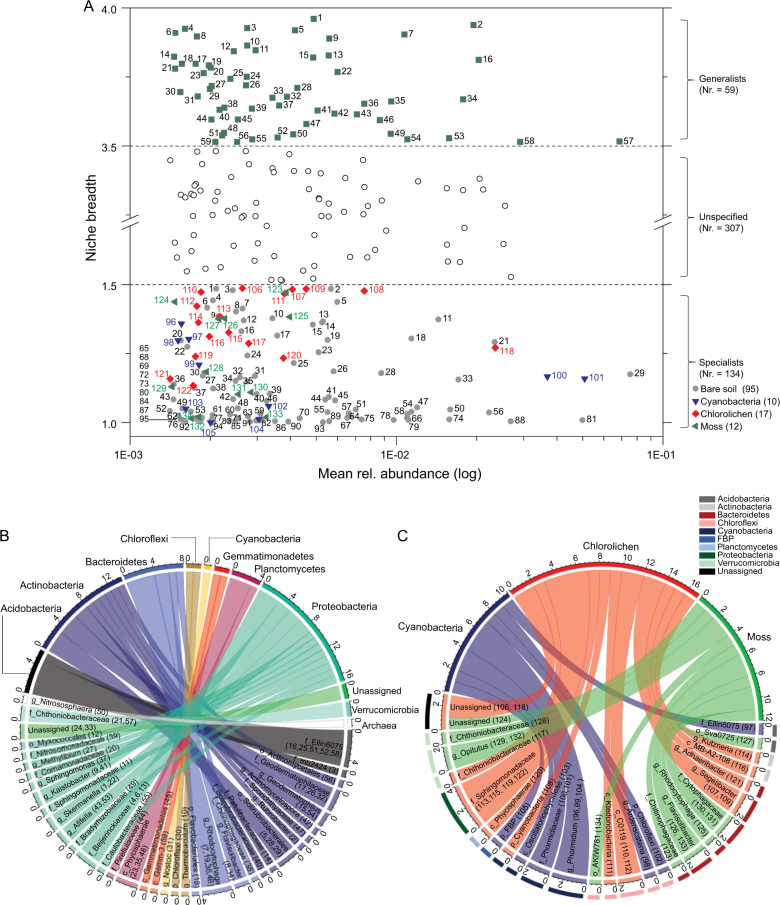

Abundant and ubiquitous members of the microbial community across all soil and biocrust samples were identified according to the two-parameter model introduced by Li et al. [44]. Using this measure, the following eight core taxa were detected at family level (ubiquity cutoff: 80%, abundance cutoff: 1%): Bradyrhizobiaceae, Rhodobiaceae, Sphingomonadaceae, Ellin6075, Chthoniobacteraceae, Rubrobacteraceae, Cytophagaceae, and Chitinophagaceae. Furthermore, we identified 59 out of 500 OTUs (11.8%) as generalists, including taxa, which were identified according to the approach by Li et al. [44] (Fig. 5a, b). 134 OTUs were defined as specialists for the four habitats (26.8%) (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Figure S4). The majority of the specialists, 95 OTUs, could be ascribed to the habitat soil.

Fig. 5.

Analysis of habitat specialists and generalists. Niche breadth (B) of OTUs identified in bare soil and different biocrust types. Each symbol represents an OTU. OTUs that are present along a wider range of habitats have a higher B value and are considered habitat generalists (numbered from 1-59), while OTUs with a B value < 1.5 are considered habitat specialists (numbered from 1-134). Numbers adjacent to points refer to numbers in brackets in B, C and S4. Open circles show OTUs that could not be defined as generalists or specialists (a). Circos plot showing taxonomic assignment for OTUs identified as generalists (b) and specialists in cyanobacteria-, chlorolichen-, and moss-dominated biocrusts (c). Specialists in bare soil are shown in Supplementary Figure S4. Numbers outside of the circles indicate the number of OTUs

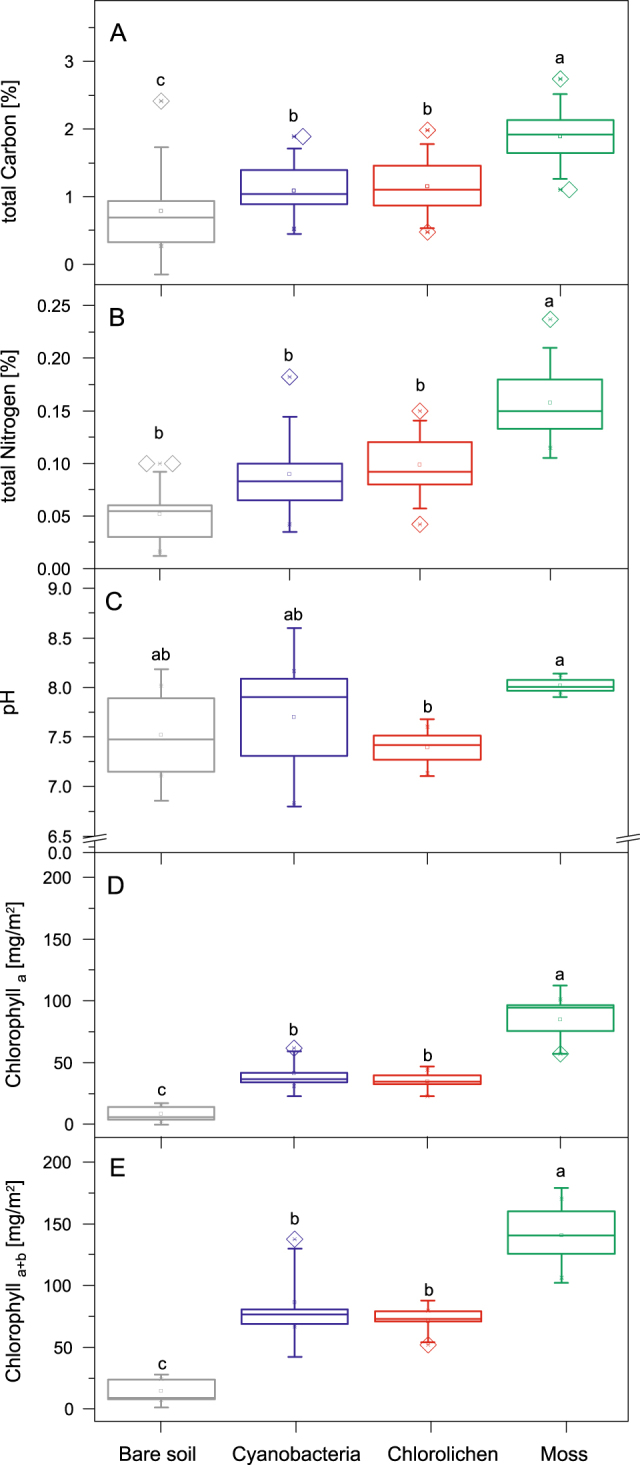

Soil parameters

Both total carbon and nitrogen contents increased with biocrust succession (Fig. 6a, b; Supplementary Table S4). Total carbon contents were significantly higher in moss-dominated compared to the other biocrust types and furthermore all crust types showed significant differences to bare soil. Nitrogen contents were significantly higher in moss-dominated biocrusts compared to bare soil and the other types of biocrusts. pH values of biocrusts and bare soil were in a neutral to weakly alkaline range (7.4–8) with moss-dominated reaching significantly higher values than chlorolichen-dominated biocrusts, whereas cyanobacteria-dominated biocrusts and bare soil did not differ significantly from them (Fig. 6c, Supplementary Table S4).

Fig. 6.

Total carbon (a), total nitrogen (b), pH (c) chlorophylla (d), and chlorophylla+b contents (e) of different types of biocrusts plus bare soil. Boxes limit the 25th- and 75th percentile with the median presented as line and mean values marked as point inside. Error bars present the 1st and 99th percentile and outliers are shown as dots below and above. Significant differences (P < 0.05) are marked by different letters

Photosynthetically active biomass measured as chlorophylla (chla) and chla+b contents showed similar patterns of increasing contents with progressing biocrust succession (Fig. 6d, e). Whereas bare soil had only small amounts of chla and chla+b, cyanobacteria- and chlorolichen-dominated biocrusts showed significantly higher chlorophyll contents in a medium range. Moss-dominated biocrusts had the highest contents with 84.9 ± 18.4 mg chla m−2 and 140.6 ± 25.6 mg chla+b m−2, being significantly higher than in all other biocrust types and in bare soil samples.

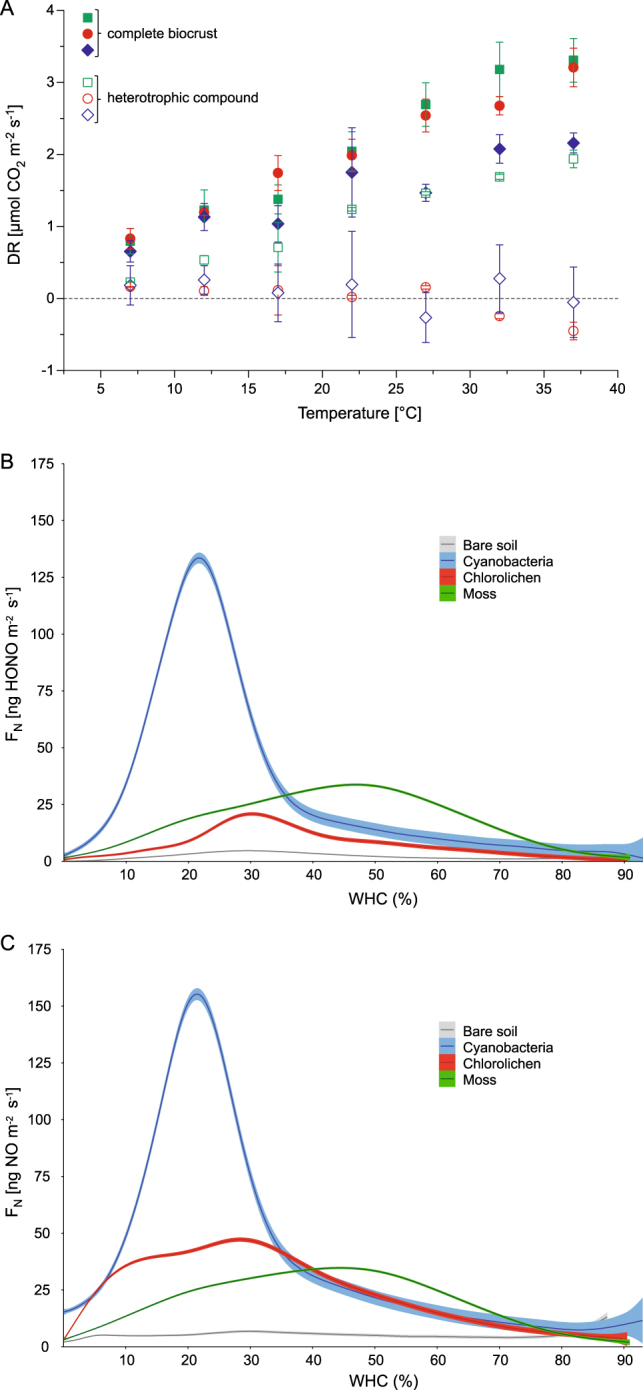

Soil respiration

Respiration of all biocrust types (complete biocrusts) increased with ascending temperature and reached highest values between 3.3 µmol CO2 m−2 s−1 for moss-dominated, 3.2 µmol CO2 m−2 s−1 for chlorolichen-dominated and 2.2 µmol CO2 m−2 s−1 for cyanobacteria-dominated biocrusts at 37 °C (Fig. 7a). Soil respiration of the heterotrophic fraction of cyanobacteria- and chlorolichen-dominated biocrusts was similar (fluctuating around zero; maximum values of 0.27 and 0.16 µmol CO2 m−2 s−1), whereas in moss-dominated biocrusts significantly higher values were reached at 37 °C (1.94 µmol CO2 m−2 s−1; Fig. 7, Supplementary Table S5).

Fig. 7.

Respiration (DR) of different biocrust types and their heterotrophic fraction at varying temperatures (a). Differently colored symbols represent mean DR values of cyanobacteria- (closed rhombus, blue), chlorolichen- (closed triangle, red), and moss-dominated biocrusts (closed square, green). DR values of the heterotrophic fraction of different biocrust types are shown as open symbols. Measurements were conducted under optimum water conditions at 380 ppm CO2 (n = 3). Characteristic emission patterns of HONO (b) and NO (c) from different biocrust types and bare soil. The flux was calculated based on four replicates of each type of biocrust by geom_smooth model in ggplot2 of R software. The upper and lower bands show the pointwise 95% confidence interval around the mean

Reactive nitrogen emissions

Characteristic HONO and NO emission patterns were observed for all types of biocrusts, whereas for bare soil no significant amounts of reactive nitrogen emissions were measured (Fig. 7b, c). Cyanobacteria-dominated biocrusts showed highest HONO and NO emissions (208 ± 15 ng m−2 s−1 of NO–N and 173 ± 18 ng m−2 s−1 of HONO–N) at a range of 0–10% of soil water content (SWC), which equals ∼20–25% water-holding capacity (WHC). Smaller HONO and NO emission were released from chlorolichen- and moss-dominated biocrusts and extended over a wider range of 0–30% SWC (∼20–80% WHC), where the highest fluxes amounted to 94.85 and 47.61 ng m−2 s−1 of NO–N and 61.86 and 46.14 ng m−2 s−1 of HONO–N, respectively. Opposed to this, the average fluxes of bare soil samples were lower by more than a factor of 20 (9 ± 3 ng m−2 s−1 for NO–N and 5 ± 2 ng m−2 s−1 for HONO–N).

Discussion

Our investigations revealed a clear shift of the heterotrophic community composition along biocrust succession, which apparently causes altered physiological properties. Also, nutrient and chlorophyll contents varied between the successional stages. Thus, we could verify our hypothesis, i.e., that the photoautotrophic organisms affect the composition of the heterotrophic community, which influences the physiological properties of the biocrusts.

Shift in diversity and relative abundance along the successional stages

We observed that 16S and 18S rRNA gene copy numbers as well as alpha diversity values were highest in late successional biocrust stages, which is in line with the results of a study conducted at the Colorado Plateau [45]. The Shannon index ranged from 8.0 to 11.2, being quite high in comparison to forests soils at Shennongjia Mountain in China, where values of 7.0 for coniferous forests up to 8.1 for evergreen broadleaved forests were determined [46]. However, it is comparable to temperate grassland and forest soils in Germany, where values of 10.1 and 9.5 were obtained, respectively [47]. The bacterial community of bare soil was different from biocrust communities and successional stage determined the assembly of heterotrophic soil communities. Besides heterotrophic organisms, cyanobacteria were also present, with the highest relative abundance in bare soil. This is consistent with the view that cyanobacteria act as pioneers in the stabilization process of soils [48, 49]. The data suggest that fractions of the bacterial community in cyanobacteria-dominated biocrusts are retained during the development of chlorolichen- and moss-dominated biocrusts. Changes of bacterial communities at different ages of biocrusts have also been reported for the Tengger Desert, China [50].

During successional dynamics in plants, key processes such as facilitation between community members, resulting in reduced environmental stress, take place [51]. Similar mechanisms probably also occur in biocrusts, e.g., via substrate stabilization and nutrient input by early colonizers, thus driving microbial succession. Our data show an increased relative abundance of members of the families Geodermatophilaceae, Bacillaceae, and Trueperaceae (Supplementary Figure S1) in early biocrust stages. Geodermatophilaceae are spore-forming and capable to grow in nutrient-poor biotopes such as dry soils or mineral rock. They have been reported to resist oxidative stress, heavy metals, exposure to high gamma ionizing radiation, UV light, as well as desiccation, and were shown to survive in the atmosphere [52]. Modestobacter versicolor for instance has been isolated from biocrusts from the Colorado Plateau in USA [53]. Similarly resistant are Trueperaceae [54] and endospores of Bacillaceae, which potentially survive unfavorable conditions for thousands of years as well as intercontinental dispersal [55]. The predominance of bacterial taxa, which are known to be highly tolerant to environmental stresses, in early biocrust stages could be linked to the successional development of biocrusts. During development, biocrusts frequently form a layered structure characterized by an upper layer colonized by heavily pigmented fungi and cyanobacteria and an underlying layer with less-UV-tolerant organisms [4]. This might create niches for less robust bacterial taxa. Analyses revealed that the relative abundance of some bacterial taxa with metabolic versatility and broadly adapted genera, decreased along succession. Examples are the family Flavobacteriaceae [56], Sporichthyaceae and Comamonadaceae [57].

Our data suggest that the dominating photoautotrophic organism may facilitate the persistence of a specific microbial community, potentially induced by locally modified environmental conditions, as e.g., light, temperature, and nutrient conditions. A previous study has shown that the composition of microbial metacommunities at lichen-rock interfaces was strongly influenced by the lichen species [58]. Similarly, research on the rhizosphere has shown that the assembly of microbiota is influenced by plant species among other factors [59]. Bare soil, but also the atmosphere can be regarded as reservoir of microorganisms and the physicochemical properties and biogeographical processes affect the microbial population of varying habitats [60, 61].

Altered microbial composition reflected by shifts in nutrient composition

Our study revealed increasing carbon and nitrogen contents from bare soil via initial to developed biocrusts (Fig. 6a, b) and statistically significant correlations between community composition and soil parameters (Supplementary Table S2). Li et al. [62] found the same trend of nutrient-level enhancement along successional stages in biocrusts from Delate Country, Inner Mongolia. Moreover, it was shown that crust bryophytes influence soil fertility not only by intercepting dust particles, but also by facilitating development of microorganism communities that increase the nutrient status of biocrusts [63]. Such an improved nutrient status within well-developed biocrusts may be linked to the abundance of biomass-degrading microorganisms in the substrate. Our data revealed that Chitinophagaceae and Cytophagaceae, cellulose and chitin-degrading taxa, are more abundant in the biocrusts compared to soil without cryptogams (Supplementary Figure S1).

Bacteria have also been shown to respond individually to different carbon sources. Cleveland et al. [64] demonstrated a shift in bacterial composition combined with increased CO2 fluxes as a result of the addition of low-molecular-weight organic carbon. Recent studies have shown that rhizodeposits such as low-molecular-mass compounds (sugars, amino acids, organic acids) and polymerized sugar are partly responsible for variations in rhizospere-associated bacteria and bulk soil microbial communities [59].

In our study, OTUs classified as Chloroflexi occurred more frequently in biocrusts as compared to bare soil. Chloroflexi have been observed to occur in close contact with Cyanobacteria in microbial mats [65]. Burow et al. [66] proposed a metabolic pathway between Microcoleus spp. fermenting photosynthates to organic acids, and Chloroflexi spp., taking these up to be stored as polyhydroxyalkanoates. This metabolic link might be a more general phenomenon which could explain the increased occurrence of OTUs classified as Chloroflexi in biocrust associated soil.

Effects of altered microbial community composition on soil respiration and reactive nitrogen gas emissions

Our results provide evidence that altered microbial communities may affect soil respiration, which is higher in moss-dominated as compared to earlier biocrust stages and bare soil (Fig. 7a). Plant cover has been shown to affect soil respiration and microbial enzyme activity in arid ecosystems [67]. Furthermore, our results are in line with findings of previous studies, where soil respiration rates have been shown to be twice as high in well-developed late compared to early successional biocrusts, and to be significantly higher in biocrust-dominated compared to open microsites with low biocrust cover [24, 68]. High respiration values of moss-dominated biocrusts may be favored by microbial decomposition of carbohydrates, as moss-dominated biocrusts comprise a lot of dead plant material. These results are in line with a previous study, which demonstrated a shift in the bacterial composition and an increase in CO2 fluxes upon the addition of low-molecular-weight organic carbon [64].

Recent studies showed that reactive nitrogen gases, such as HONO, NO and the greenhouse gas N2O (nitrous oxide) are emitted by biocrusts [43, 69, 70]. Moreover, gas fluxes from soils are affected by soil pH, nitrite concentration, and also the presence of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria [71–73]. In our laboratory study, the HONO and NO emission patterns changed with the successional stages of biocrusts, resulting in a sharp peak for cyanobacteria-dominated biocrusts and a wider range of moderately increased emissions for chlorolichen- and moss-dominated biocrusts (Fig. 7). The sharp peak of cyanobacteria-dominated biocrusts at low soil water contents may indicate that NO and HONO are emitted under oxic conditions during nitrification. Our results suggest an increased relative abundance of the family Nitrospiraceae in cyanobacteria- compared to moss-dominated biocrusts (Fig. 4a). Nitrospira has recently been described as the first bacterial genus observed to conduct complete nitrification, i.e., ammonium and nitrite oxidation [74]. Also Nitrososphaeraceae revealed an increased relative abundance in cyanobacteria- compared to moss-dominated biocrusts and bare soil (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Figure S3A). Archaeal populations have previously been observed in biocrusts [75, 76] and archaeal amoA genes (Nitrososphaera) are widely present in biocrusts in desert regions across the United States, indicating that archaea are likely involved in ammonia oxidation in biocrusts [77]. Thus, peaking emissions of HONO and NO in cyanobacteria-dominated biocrusts could be explained by increased abundance of nitrifying bacteria and archaea.

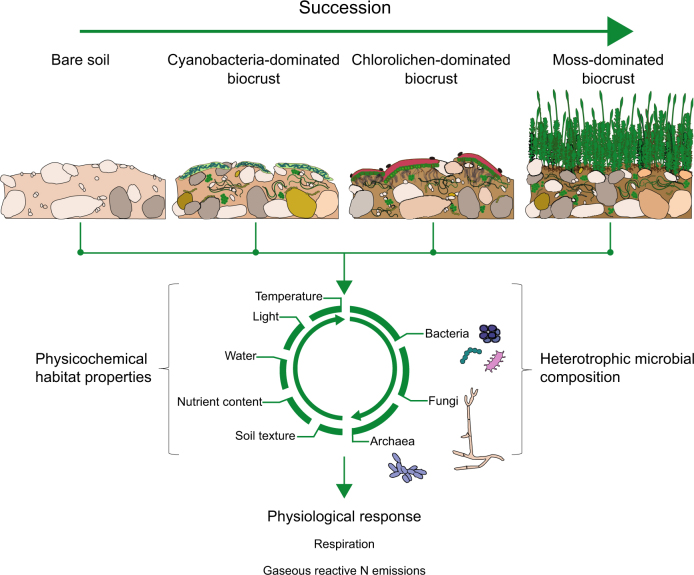

Conclusions

Our study, to our knowledge, is one of the first investigating the microbial community composition within biocrusts along different successional stages and linking these with their physiological properties. While the succession of photoautotrophs, used for classification of crust types, has been known and modeled [1, 9, 78], we show here that they strongly affect the heterotrophic microbial composition and the physiological properties, probably via impacting the physicochemical habitat properties (Fig. 8). The community composition combined with particular habitat conditions likely determines the physiological properties of different successional stages of biocrusts. These aspects need to be incorporated in future ecological models, which help to understand the functioning and vulnerability of biocrusts towards disturbance such as land use alterations and climate change.

Fig. 8.

Schematic diagram showing the successional development of biocrusts. Along succession, the heterotrophic community as well as physicochemical properties within biocrusts change, causing altered physiological properties

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the German Research Foundation (Project numbers WE 2393/2-1, WE 2393/2-2). BW would like to thank Paul Crutzen for awarding her a Nobel Laureate Fellowship (2013–2015). Research in South Africa was conducted with South African research permits (No. 22/2008, 38/2009, 257/2010, 1904/2013) and export permits. We thank Timm Hoffman (Cape Town) and Burkhard Büdel (Kaiserslautern) for the provision of research facilities, Burkhard Büdel for his offer to adapt his biocrust illustrations, Max Paul for his assistance in field work and Sebastian Brill in figure preparation.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

:The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Stefanie Maier and Alexandra Tamm contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41396-018-0062-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Stefanie Maier, Phone: ++49 0 6131 305 7004, Email: s.maier@mpic.de.

Bettina Weber, Phone: ++49 0 6131 305 7501, Email: b.weber@mpic.de.

References

- 1.Büdel B, Darienko T, Deutschewitz K, Dojani S, Friedl T, Mohr KI, et al. Southern african biological soil crusts are ubiquitous and highly diverse in drylands, being restricted by rainfall frequency. Microb Ecol. 2009;57:229–47. doi: 10.1007/s00248-008-9449-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belnap J, Weber B, Büdel B. Biological soil crusts as an organizing principle in drylands. In: Weber B, Büdel B, Belnap J, editors. Biological soil crusts: an organizing principle in drylands. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2016. p. 3–13.

- 3.Frahm J-P, Schumm F, Stapper NJ. Epiphytische Flechten als Umweltgütezeiger: eine Bestimmungshilfe. Norderstedt: Books on Demand, Norderstedt; 2010.

- 4.Pointing SB, Belnap J. Microbial colonization and controls in dryland systems. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012;10:551–62. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Green ATG, Sancho LG, Pintado A. Ecophysiology of Desiccation/Rehydration Cycles in Mosses and Lichens. In: Lüttge U, Beck E, Bartels D, editors. Plant Desiccation Tolerance. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2011. pp. 89–120. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evans RD, Belnap J, Garcia-Pichel E, Phillips SL. Global change and the future of biological soil crusts. In: Belnap J, Lange OL, editors. Biological soil crusts: structure, function, and management. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2003. p. 417–29.

- 7.Bowker MA, Belnap J, Miller ME. Spatial modeling of biological soil crusts to support rangeland assessment and monitoring. Rangel Ecol Manag. 2006;59:519–29. doi: 10.2111/05-179R1.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weber B, Graf T, Bass M. Ecophysiological analysis of moss-dominated biological soil crusts and their separate components from the Succulent Karoo, South Africa. Planta. 2012;236:129–39. doi: 10.1007/s00425-012-1595-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dojani S, Büdel B, Deutschewitz K, Weber B. Rapid succession of Biological Soil Crusts after experimental disturbance in the Succulent Karoo, South Africa. Appl Soil Ecol. 2011;48:263–9. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2011.04.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bamforth SS. Protozoa of biological soil crusts of a cool desert in Utah. J Arid Environ. 2008;72:722–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaridenv.2007.08.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pan H, Cheng Z, Zhang Y, Mu S, Qi X. Research progress and developing trends on microorganisms of Xinjiang specific environments. J Arid Land. 2010;2:51–6. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seppelt RD, Downing AJ, Deane-Coe KK, Zhang Y, Zhang J. Bryophytes within biological soil crusts. In: Weber B, Büdel B, Belnap J, editors. Biological soil crusts: an organizing principle in drylands. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2016. p. 101–20.

- 13.Weber B, Bowker M, Zhang Y, Belnap J. Natural recovery of biological soil crusts after disturbance. In: Weber B, Büdel B, Belnap J, editors. Biological soil crusts: an organizing principle in drylands. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2016. p. 479–98.

- 14.Wu N, Zhang YM, Pan HX, Zhang J. The role of nonphotosynthetic microbes in the recovery of biological soil crusts in the Gurbantunggut desert, Northwestern China. Arid L Res Manag. 2010;24:42–56. doi: 10.1080/15324980903439503. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pepe-Ranney C, Koechli C, Potrafka R, Andam C, Eggleston E, Garcia-Pichel F, et al. Non-cyanobacterial diazotrophs mediate dinitrogen fixation in biological soil crusts during early crust formation. ISME J. 2015;10:287–98. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brooker RW, Maestre FT, Callaway RM, Lortie CL, Cavieres LA, Kunstler G, et al. Facilitation in plant communities: The past, the present, and the future. J Ecol. 2008;96:18–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2008.01373.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Colesie C, Scheu S, Green ATG, Weber B, Wirth R, Büdel B. The advantage of growing on moss: Facilitative effects on photosynthetic performance and growth in the cyanobacterial lichen Peltigera rufescens. Oecologia. 2012;169:599–607. doi: 10.1007/s00442-011-2224-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Breen K, Lévesque E. Proglacial succession of biological soil crusts and vascular plants: biotic interactions in the high Arctic. Can J Bot. 2006;84:1714–31. doi: 10.1139/b06-131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marleau JN, Jin Y, Bishop JG, Fagan WF, Lewis MA. A stoichiometric model of early plant primary succession. Am Nat. 2011;177:233–45. doi: 10.1086/658066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Belnap J, Büdel B, Lange OL. Biological soil crusts: characteristics and distribution. In: Belnap J, Lange OL, editors. Biological soil crusts: structure, function, and management. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2003. p. 3–30.

- 21.Darby BJ, Neher DA. Microfauna within biological soil crusts. In: Weber B, Büdel B, Belnap J, editors. Biological soil crusts: an organizing principle in drylands. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2016. p 139-58.

- 22.Elbert W, Weber B, Burrows S, Steinkamp J, Büdel B, Andreae MO, et al. Contribution of cryptogamic covers to the global cycles of carbon and nitrogen. Nat Geosci. 2012;5:459–62. doi: 10.1038/ngeo1486. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walvoord MA. A reservoir of nitrate beneath desert soils. Science. 2003;302:1021–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1086435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Castillo-Monroy AP, Maestre FT, Rey A, Soliveres S, García-Palacios P. Biological soil crust microsites are the main contributor to soil respiration in a semiarid ecosystem. Ecosystems. 2011;14:835–47. doi: 10.1007/s10021-011-9449-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomas AD, Hoon SR. Carbon dioxide fluxes from biologically-crusted Kalahari Sands after simulated wetting. J Arid Environ. 2010;74:131–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaridenv.2009.07.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomas AD, Hoon SR, Linton PE. Carbon dioxide fluxes from cyanobacteria crusted soils in the Kalahari. Appl Soil Ecol. 2008;39:254–63. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2007.12.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cable JM, Ogle K, Williams DG, Weltzin JF, Huxman TE. Soil texture drives responses of soil respiration to precipitation pulses in the sonoran desert: implications for climate change. Ecosystems. 2008;11:961–79. doi: 10.1007/s10021-008-9172-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Austin AT, Yahdjian L, Stark JM, Belnap J, Porporato A, Norton U, et al. Water pulses and biogeochemical cycles in arid and semiarid ecosystems. Oecologia. 2004;141:221–35. doi: 10.1007/s00442-004-1519-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fierer N, Schimel JP. A proposed mechanism for the pulse in carbon dioxide production commonly observed following the rapid rewetting of a dry soil. Soil Sci Soc Am J. 2003;67:798. doi: 10.2136/sssaj2003.0798. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jarvis P, Rey A, Petsikos C, Wingate L, Pereira J, Banza J, et al. Drying and wetting of Mediterranean soils stimulates decomposition and carbon dioxide emission: the ‘Birch effect’ †. Tree Physiol. 2007;27:929–40. doi: 10.1093/treephys/27.7.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sponseller R. Precipitation pulses and soil CO 2 flux in a Sonoran Desert ecosystem. Glob Chang Biol. 2007;13:426–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2006.01307.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borken W, Matzner E. Reappraisal of drying and wetting effects on C and N mineralization and fluxes in soils. Glob Chang Biol. 2009;15:808–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2008.01681.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maestre FT, Bowker M, Escolar C, Puche MD, Soliveres S, Maltez-Mouro S, et al. Do biotic interactions modulate ecosystem functioning along stress gradients? Insights from semi-arid plant and biological soil crust communities. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2010;365:2057–70. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Jaarsveld E. The Succulent riches of South Africa and Namibia. ALOE. 1987;24:45–92. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weber B, Olehowski C, Knerr T, Hill J, Deutschewitz K, Wessels DCJ, et al. A new approach for mapping of Biological Soil Crusts in semidesert areas with hyperspectral imagery. Remote Sens Environ. 2008;112:2187–201. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2007.09.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dojani S, Kauff F, Weber B, Büdel B. Genotypic and phenotypic diversity of cyanobacteria in biological soil crusts of the succulent Karoo and Nama Karoo of Southern Africa. Microb Ecol. 2014;67:286–301. doi: 10.1007/s00248-013-0301-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lauber CL, Hamady M, Knight R, Fierer N. Pyrosequencing-based assessment of soil pH as a predictor of soil bacterial community structure at the continental scale. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:5111–20. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00335-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kozich JJ, Westcott SL, Baxter NT, Highlander SK, Schloss PD. Development of a dual-index sequencing strategy and curation pipeline for analyzing amplicon sequence data on the miseq illumina sequencing platform. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:5112–20. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01043-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ronen R, Galun M. Pigment extraction from lichens with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and estimation of chlorophyll degradation. Environ Exp Bot. 1984;24:239–45. doi: 10.1016/0098-8472(84)90004-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Streubing L, Fangmeier A. Abiotische Faktoren: Methoden zur ökologischen Bewertung von Böden, Klima und Immissionen. In: Streubing L, Fangmeier A, editors. Pflanzenökologisches Praktikum: Gelände- und Laborpraktikum der terrestrischen Pflanzenökologie. Stuttgart: Verlag Eugen Ulmer; 1992. p. 16–51.

- 41.Honegger R. The impact of different long-term storage conditions on the viability of lichen-forming ascomycetes and their green algal photobiont, Trebouxia spp. Plant Biol. 2003;5:324–30. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-40794. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu D, Kampf CJ, Pöschl U, Oswald R, Cui J, Ermel M, et al. Novel tracer method to measure isotopic labeled gas-phase nitrous acid (HO 15 NO) in. Environ Sci Technol. 2014;48:8021–7. doi: 10.1021/es501353x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weber B, Wu D, Tamm A, Ruckteschler N, Rodríguez-Caballero E, Steinkamp J, et al. Biological soil crusts accelerate the nitrogen cycle through large NO and HONO emissions in drylands. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:15384–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1515818112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li H, Colica G, Wu PP, Li D, Rossi F, De Philippis R, et al. Shifting Species Interaction in Soil Microbial Community and Its Influence on Ecosystem Functions Modulating. Microb Ecol. 2013;65:700–8. doi: 10.1007/s00248-012-0171-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Garcia-Pichel F, Johnson SL, Youngkin D, Belnap J. Small-scale vertical distribution of bacterial biomass and diversity in biological soil crusts from arid lands in the Colorado plateau. Microb Ecol. 2003;46:312–21. doi: 10.1007/s00248-003-1004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang Y, Cong J, Lu H, Li G, Xue Y, Deng Y, et al. Soil bacterial diversity patterns and drivers along an elevational gradient on Shennongjia Mountain, China. Microb Biotechnol. 2015;8:739–46. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.12288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaiser K, Wemheuer B, Korolkow V, Wemheuer F, Nacke H, Schöning I, et al. Driving forces of soil bacterial community structure, diversity, and function in temperate grasslands and forests. Sci Rep. 2016;6:1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41598-016-0001-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Garcia-Pichel F, López-Cortés A, Nübel U. Phylogenetic and morphological diversity of cyanobacteria in soil desert crusts from the colorado plateau phylogenetic and morphological diversity of cyanobacteria in soil desert crusts from the Colorado Plateau. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:1902–10. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.4.1902-1910.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Garcia-Pichel F, Wojciechowski MF. The evolution of a capacity to build supra-cellular ropes enabled filamentous cyanobacteria to colonize highly erodible substrates. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:4–9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu L, Liu Y, Zhang P, Song G, Hui R, Wang Z, et al. Development of bacterial communities in biological soil crusts along a revegetation chronosequence in the Tengger Desert, northwest China. Biogeosciences. 2017;14:3801–14. doi: 10.5194/bg-14-3801-2017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fierer N, Nemergut D, Knight R, Craine JM. Changes through time: Integrating microorganisms into the study of succession. Res Microbiol. 2010;161:635–42. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Normand P, Daffonchio D, Gtari M. The prokaryotes: Actinobacteria. In: Rosenberg E, DeLong EF, Lory S, Stackebrandt E, Thompson F, editors. The prokaryotes: Actinobacteria. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2014. p. 361–79.

- 53.Reddy GSN, Potrafka RM, Garcia-Pichel F. Modestobacter versicolor sp. nov., an actinobacterium from biological soil crusts that produces melanins under oligotrophy, with emended descriptions of the genus Modestobacter and Modestobacter multiseptatus Mevs et al. 2000. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2007;57:2014–20. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64932-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Albuquerque L, Simões C, Nobre FM, Pino NM, Battista JR, Silva MT, et al. Truepera radiovictrix gen. nov., sp. nov., a new radiation resistant species and the proposal of Trueperaceae fam. nov. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2005;247:161–9. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mandic-Mulec I, Stefanic P, Elsas JD (2015). Ecology of Bacillaceae. 1–24. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Bernardet J-F, Nakagawa Y. An introduction to the family Flavobacteriaceae. In: Dworkin M, Falkow S, Rosenberg E, Stackebrandt E, editors. The prokaryotes.Singapore: Springer; 2006. p. 455–80.

- 57.Willems A. The family Comamonadaceae. In: The Prokaryotes. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2014. p. 777–851.

- 58.Bjelland T, Grube M, Hoem S, Jorgensen SL, Daae FL, Thorseth IH, et al. Microbial metacommunities in the lichen-rock habitat. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2011;3:434–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2010.00206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Philippot L, Raaijmakers JM, Lemanceau P, van der Putten WH. Going back to the roots: the microbial ecology of the rhizosphere. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013;11:789–99. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Després VR, Huffman AJ, Burrows SM, Hoose C, Safatov AS, Buryak G, et al. Primary biological aerosol particles in the atmosphere: a review. Tellus B Chem Phys Meteorol. 2012;64:15598. doi: 10.3402/tellusb.v64i0.15598. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fröhlich-Nowoisky J, Kampf CJ, Weber B, Huffman AJ, Pöhlker C, Andreae MO, et al. Bioaerosols in the Earth system: Climate, health, and ecosystem interactions. Atmos Res. 2016;182:346–76. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosres.2016.07.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li K, Bihan M, Methé BA. Analyses of the stability and core taxonomic membership of the human microbiome. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e63139. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhao Y, Qin N, Weber B, Xu M. Response of biological soil crusts to raindrop erosivity and underlying influences in the hilly Loess Plateau region, China. Biodivers Conserv. 2014;23:1669–86. doi: 10.1007/s10531-014-0680-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cleveland CC, Nemergut DR, Schmidt SK, Townsend AR. Increases in soil respiration following labile carbon additions linked to rapid shifts in soil microbial community composition. Biogeochemistry. 2006;82:229–40. doi: 10.1007/s10533-006-9065-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ley RE, Harris KJ, Wilcox J, Spear JR, Miller SR, Bebout BM, et al. Unexpected diversity and complexity of the guerrero negro hypersaline microbial mat. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:3685–95. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.5.3685-3695.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Burow LC, Woebken D, Marshall IPG, Lindquist E, Bebout BM, Prufert-Bebout L, et al. Anoxic carbon flux in photosynthetic microbial mats as revealed by metatranscriptomics. ISME J. 2013;7:817–29. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bolton H, Smith JL, Link SO. Soil microbial biomass and activity of a disturbed and undisturbed shrub-steppe ecosystem. Soil Biol Biochem. 1993;25:545–52. doi: 10.1016/0038-0717(93)90192-E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Escolar C, Maestre FT, Rey A. Biocrusts modulate warming and rainfall exclusion effects on soil respiration in a semi-arid grassland. Soil Biol Biochem. 2015;80:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2014.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lenhart K, Bunge M, Ratering S, Neu TR, Schüttmann I, Greule M, et al. Evidence for methane production by saprotrophic fungi. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1046. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lenhart K, Weber B, Elbert W, Steinkamp J, Clough T, Crutzen P, et al. Nitrous oxide and methane emissions from cryptogamic covers. Glob Chang Biol. 2015;21:3889–900. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Oswald R, Behrendt T, Ermel M, Wu D, Su H, Cheng Y, et al. HONO Emissions from Soil Bacteria as a Major Source of Atmospheric Reactive Nitrogen. Science. 2013;341:1233–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1242266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Scharko NK, Schütte UME, Berke AE, Banina L, Peel HR, Donaldson MA, et al. Combined flux chamber and genomics approach links nitrous acid emissions to ammonia oxidizing bacteria and Archaea in urban and agricultural soil. Environ Sci Technol. 2015;49:13825–34. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b00838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Su H, Cheng Y, Oswald R, Behrendt T, Trebs I, Meixner FX, et al. Soil nitrite as a source of atmospheric HONO and OH radicals. Science. 2011;333:1616–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1207687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Daims H, Lebedeva EV, Pjevac P, Han P, Herbold C, Albertsen M, et al. Complete nitrification by Nitrospira bacteria. Nature. 2015;528:504–9. doi: 10.1038/nature16461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Johnson SL, Budinoff CR, Belnap J, Garcia-Pichel F. Relevance of ammonium oxidation within biological soil crust communities. Environ Microbiol. 2005;7:1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2004.00649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Soule T, Anderson IJ, Johnson SL, Bates ST, Garcia-Pichel F. Archaeal populations in biological soil crusts from arid lands in North America. Soil Biol Biochem. 2009;41:2069–74. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2009.07.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Marusenko Y, Bates ST, Anderson I, Johnson SL, Soule T, Garcia-pichel F. Ammonia-oxidizing archaea and bacteria are structured by geography in biological soil crusts across North American arid lands. Ecol Process. 2013;2:1–10. doi: 10.1186/2192-1709-2-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Read CF, Elith J, Vesk PA. Testing a model of biological soil crust succession. J Veg Sci. 2016;27:176–86. doi: 10.1111/jvs.12332. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gundlapally SR, Garcia-Pichel F. The community and phylogenetic diversity of biological soil crusts in the Colorado Plateau studied by molecular fingerprinting and intensive cultivation. Microb Ecol. 2006;52:345–57. doi: 10.1007/s00248-006-9011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.