Abstract

Insecticide resistance is a serious concern in modern agriculture, and an understanding of the underlying evolutionary processes is pivotal to prevent the problem. The bean bug Riptortus pedestris, a notorious pest of leguminous crops, acquires a specific Burkholderia symbiont from the environment every generation, and harbors the symbiont in the midgut crypts. The symbiont’s natural role is to promote insect development but the insect host can also obtain resistance against the insecticide fenitrothion (MEP) by acquiring MEP-degrading Burkholderia from the environment. To understand the developing process of the symbiont-mediated MEP resistance in response to the application of the insecticide, we investigated here in parallel the soil bacterial dynamics and the infected gut symbionts under different MEP-spraying conditions by culture-dependent and culture-independent analyses, in conjunction with stinkbug rearing experiments. We demonstrate that MEP application did not affect the total bacterial soil population but significantly decreased its diversity while it dramatically increased the proportion of MEP-degrading bacteria, mostly Burkholderia. Moreover, we found that the infection of stinkbug hosts with MEP-degrading Burkholderia is highly specific and efficient, and is established after only a few times of insecticide spraying at least in a field soil with spraying history, suggesting that insecticide resistance could evolve in a pest bug population more quickly than was thought before.

Introduction

Chemical insecticides are used worldwide for controlling agricultural and medical pests. Their use has greatly contributed to the progress of modern agriculture and public health. On the other hand, use of insecticides has frequently led to many problems, including the development of insecticide resistance in pest populations. Mechanisms underpinning the insecticide resistance are diverse, including alteration of drug target sites, upregulation of degrading enzymes and enhancement of drug excretion [1–3], all of which have been generally attributable to mutational changes in the pests’ own genomes. Recently, we revealed a novel type of insecticide resistance in the bean bug Riptortus pedestris and phylogenetically related species, wherein the stinkbugs become resistant against an organophosphorus insecticide, fenitrothion, by acquiring fenitrothion-degrading symbionts from environmental soil [4]. Since this first report, symbiont-mediated insecticide resistance has been reported or suggested in other insects, including lepidopteran pests [5–7], Drosophila [8], and other fruit flies [9], but how the symbiont-mediated insecticide resistance develops over time, after application of the insecticide, has been poorly investigated.

Riptortus pedestris, known as a notorious pest of leguminous crops [10], is associated with a gut bacterial symbiont of the genus Burkholderia in a posterior region of the midgut [11–13]. In the specialized symbiotic organ, an adult insect harbors as many as 108 cells of the Burkholderia symbiont [14], enhancing growth and fecundity of the host insect [15], indicating the beneficial nature of the symbiotic association. In contrast to vertical symbiont transmission ubiquitously found in many insects [16], R. pedertris acquires the symbiont from ambient soil every host generation [17]. Broad surveys have revealed that the Burkholderia symbiont is widely associated with the members of the stinkbug superfamilies Coreoidea and Lygaeoidea [11, 18–22]. The stinkbug-associated Burkholderia are genetically diverse but clustered in a specific clade, called “Stinkbug-associated Beneficial and Environmental (SBE)” group [11, 13]. Recent studies reported that a different group of Burkholderia, belonging to the “plant-associated beneficial and environmental (PBE)” group, is associated with the family Largidae of the superfamily Pyrrhocoroidea [23–25].

Fenitrothion, or O,O-dimethyl O-(4-nitro-m-tolyl) phosphorothioate, which is generally known as “MEP”, is one of the most popular organophosphorus insecticides used worldwide, which inhibits arthropod acetylcholine esterases and exhibits both oral and percutaneous arthropod-specific toxicities [26]. Previous studies have repeatedly isolated MEP-degrading Pseudomonas, Flavobacterium (reclassified as Shingobium [27]), Cupriavidus, Corynebacterium, Arthrobacter, Sphingomonas, Pandoraea, Dyella, Achromobacter, Ralstonia, and Burkholderia from agricultural field soils [28–32]. These bacteria are able to hydrolyze fenitrothion into 3-methyl-4-nitrophenol and dimethyl thiophosphate, compounds with little insecticidal activity, and metabolize the degradation product as a carbon source for their growth [33]. Although MEP-degraders are not generally observed in untreated soil (or are under the detection limit), intense applications of MEP to soils drastically enrich the MEP-degrading bacteria in the soil [29, 31]. Indeed, enrichment of MEP-degraders in soil was recently observed in natural sugarcane fields in Southern islands of Japan [34], where MEP has been regularly used to prevent sugarcane pests. During the enrichment, the community structure of MEP-degrading bacteria dynamically changes, depending on their MEP-assimilation abilities and the MEP-spraying frequency [35].

Stinkbugs specifically select SBE- or PBE-group Burkholderia [11, 25], by use of a sophisticated symbiont-sorting mechanism developed in the midgut [36]. Hence we assumed that transmission of the MEP-degrading Burkholderia from the soil to stinkbugs is a two-step selection process [35]: first, the selective growth of specific free-living Burkholderia symbionts that can degrade MEP as a carbon source, and thereby modifying the community structure of Burkholderia species/strains in the soil; and second, the successful infection of such Burkholderia symbiont variants within the host stinkbugs. Previous studies have focused only on the first adaptation step that occurs in soil bacteria in the soil environment [29, 31, 35], whereas because of the lack of stinkbug rearing experiments on sprayed soil, it is not known how the first and second selection steps are connected. Thus, we currently have no knowledge of how alteration of soil bacterial communities in response to MEP spraying influences the infection frequency of MEP-degrading symbionts in the host stinkbugs. To determine the developing process of the symbiont-mediated insecticide resistance, we investigate soil bacterial dynamics and infected gut symbionts in parallel under different MEP-spraying conditions by culture-dependent and -independent analyses, in conjunction with stinkbug rearing experiments.

Materials and methods

Insecticide-spraying experiments

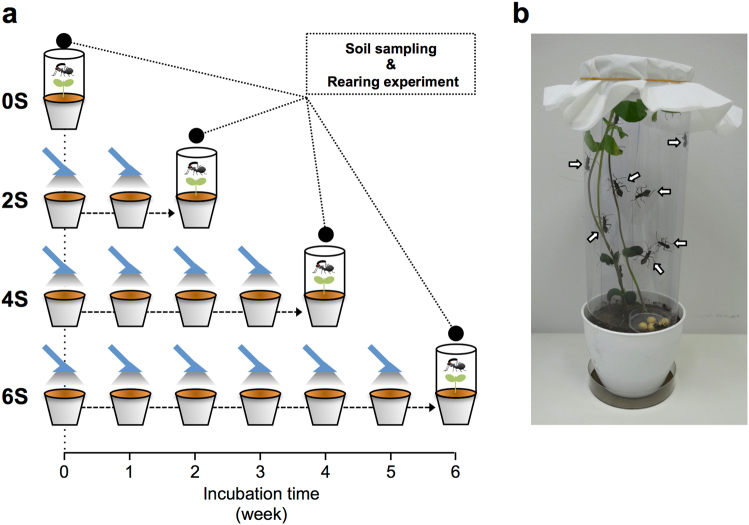

We collected soil from an agricultural field on which MEP has been sprayed frequently for at least 4 years prior to collection (Supplementary Information). The experimental design of the insecticide-spraying test is shown in Fig. 1. Approximately 150 g (dry weight) of the sieved soil was transferred into plastic pots (10 × 8 cm; opening diameter × depth). Each potted-soil was sprayed once a week with MEP either for 2 weeks (i.e., two-times spraying), four weeks (i.e., four-times spraying), or 6 weeks (i.e., six-times spraying), and the resulting soils were designated as two-times-sprayed soil (2S), four-times-sprayed soil (4S) and six-times-sprayed soil (6S), respectively. As a control, untreated soil, or 0-time-sprayed soil (0S) was investigated. Each spraying experiment was performed in triplicate. MEP spraying treatment, pot maintenance, and soil samplings were performed as previously described ([29]; Supplementary Information).

Fig. 1.

Experimental design to elucidate the infection dynamics of MEP-degrading bacteria from soil to insect. a Schema of the MEP-spraying treatment of soils and the insect rearing experiment. In addition to untreated soil (0S), field-collected soils were weekly treated with MEP either two times (2S), four times (4S), or six times (6S). One week after the final MEP-spraying, soil samples were collected from each of the MEP-treated pots, and the remaining soils were used for the insect rearing experiment. b An image of a soybean pot for the insect rearing experiment. Arrows indicate fourth instar nymphs of R. pedestris. After adult emergence, insects were collected and subjected to culture-dependent and culture-independent analyses, whose results were compared with those of soils

Culture-dependent and -independent analyses of soil microbiota

Density and diversity of MEP-degrading bacteria in soils were examined by culture-dependent analyses; the colony forming units (CFU) counting and taxonomy identification [29]. Additionally, community structure and abundance of soil microbiota were investigated by culture-independent analyses; the deep sequencing and quantitative PCR of bacterial 16S rRNA genes [29]. Full methods are described in Supplementary Information.

Insect rearing experiment on the MEP-sprayed soils

Riptortus pedestris was reared from hatch to adulthood on the soils differentially treated with MEP, i.e., the 0S–6S, and then the infection frequency of MEP-degrading bacteria was determined. The experimental design is shown in Fig. 1. Each spraying experiment was performed in triplicate. After soil samples were collected from the S0–S6, soybean plants (Glycine max) germinated from briefly sterilized seeds (dipped in 70% ethanol for 5 min) were potted in these soils, on which hatchlings of the bean bug were reared. Each of the pots included three soybean plants and 15 individuals of first instar nymphs, and was supplied with five dry soybean seeds as insect food. The pots were maintained under a long-day regimen (16 h light, 8 h dark) until adulthood of the insects. The rearing time in the pots was ~20–22 days. From each pot, five adults were randomly selected for further analyses.

After adult emergence, the symbiotic organ (crypt-bearing midgut posterior region) was dissected and subjected to a MEP-degradation assay as previously described ([4]; Supplementary Information). MEP-degradation positive samples were divided in half and subjected to further analyses: one part for the culture-dependent analysis and the other for the culture-independent analysis, as described for soil in Supplementary Information.

Infection dynamics of MEP-degrading symbionts in crop fields

The soil-to-insect infection dynamics of MEP-degrading bacteria in crop fields were investigated in sugarcane fields in Minami-Daito Island, Okinawa, Japan (25°50′N, 131°14′E, altitude of 30–40 m). In this island, most of the sugarcane fields have been treated regularly with MEP for years, resulting in natural occurrence of MEP-degrading bacteria in field soil [34], and natural infection of MEP-degrading Burkholderia in a sugarcane pest, Cavelerius saccharivorus (superfamily Lygaeoidea; family Blissidae), commonly known as “chinch bug” [4]. This species also acquires SBE Burkholderia from environment every generation [19]. Chinch bug adults are short-winged and rarely migrate between sugarcane fields [37]. It is accordingly assumed that chinch bugs collected in a given field are highly likely to have grown and acquired symbionts in the same field. Because of its restricted mobility, this species is considered to be an ideal model for investigating the soil-to-insect infection dynamics of MEP-degrading bacteria under natural conditions. Long-winged adults do occasionally emerge under high-density conditions to enable escape from such unfavorable situations [37]. The fields investigated in this study were sprayed with MEP one to nine times during 2010–2013 seasons [34]. Field soils and inhabiting short-wing adults were collected together on seven randomly selected sugarcane fields in May 2013. In each of the fields, surface soil samples were collected and subjected to CFU counting. To reveal infection frequency of MEP-degrading bacteria in the chinch bug populations, the symbiotic organ of specimens was dissected and subjected to the MEP-degradation assay (Supplementary Information).

Methods for phylogenetic analysis and statistical analysis are described in Supplementary Information.

Results

Culture-dependent analysis of the population dynamics of MEP-degrading Burkholderia in MEP-sprayed soil

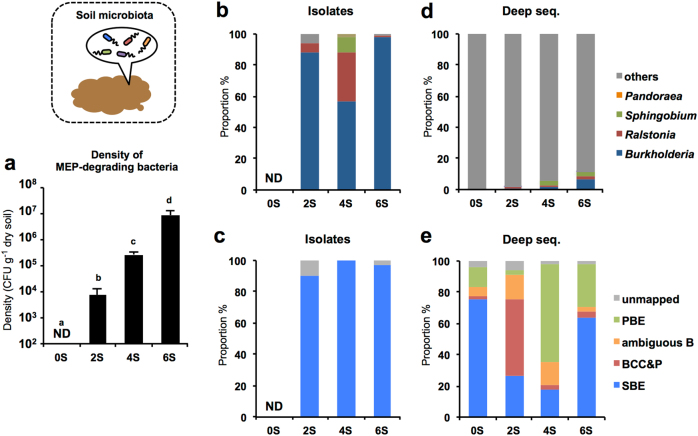

Whereas the CFUs of MEP-degrading bacteria were below the detection limit (<102 cfu g−1 dry soil) in the untreated soil (0S), MEP-degraders were detected after the second treatment with MEP (Fig. 2a). The CFU of MEP-degrading bacteria gradually increased with the MEP-spraying frequency, and reached 8.8 ± 4.5 × 106 cfu g−1 soil (mean ±Standard deviation [SD]; n = 3) after the sixth treatment. The MEP-degrading bacteria were identified by sequencing of their 16S rRNA genes, revealing that most of the degraders were of the genus Burkholderia (85.2% in total; Burkholderia strains/soil-derived isolates in total = 144/169) (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Population dynamics of MEP-degrading bacteria in sprayed soils. a Density of MEP-degrading bacteria in MEP-sprayed soils. Mean ± SD (n = 3) is shown. Values with different letter are significantly difference (p < 0.05, ANOVA with Tukey’s honestly significant difference test). b, c Culture dependent analysis of MEP-degrading bacteria isolated from insects. From 2, 4, and 6S soils, respectively 34, 44, and 91 colonies were isolated and identified. d, e Culture independent analysis (deep sequencing) of soil microbiota before and after MEP spraying. Genus-level b, d and Burkholderia group-level (c, e) compositions are shown. Sequences showing <99.5% identity against reference Burkholderia sequences are depicted as “unmapped”. Data shown in (d) and (e) are averages; the corresponding data of all replicates is shown in Supplementary Fig. S5a and b. ND: not detected

The genus Burkholderia consists of over 100 species which are classified into three distinct groups in terms of their function and specificity to host organisms [13] (Supplementary Fig. S1a and Table S1). The Burkholderia cepacia complex and B. pseudomallei (BCC&P) group includes notorious zoonotic species and crop pathogens [38, 39]; the PBE group includes nodule symbionts of some leguminous plants and a number of plant growth promoting species [40]; the SBE group includes a number of species/strains of stinkbug symbionts, as well as the B. glathei complex and leaf gall-associated species [41, 42]. These groups correspond to distinct phylogenetic clades within the Burkholderia genus (Supplementary Fig. S1a and Table S1). The phylogenetic analysis revealed that most of the MEP-degrading Burkholderia isolated from soils belong to SBE (95.8%; SBE strains/Burkholderia strains = 138/144) (Fig. 2c), specifically OTU01, 02 and 04 (Supplementary Fig. S2a).

Deep sequencing analysis of the Burkholderia population dynamics in MEP-sprayed soil

Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) indicated that MEP-spraying dramatically changed the community structure of the soil microbiota (Supplementary Fig. S3a), wherein Burkholderia, Sphingobium, Ralstonia, Nevskia, Methylobacterium, and Methylophilus consistently increased during the spraying (Supplementary Fig. S4), as also reported in our previous study [29]. In relative abundance, Burkholderia (i.e., all reads assigned to the genus Burkholderia) was only 0.06 ± 0.01% (mean ± SD) before treatment, while the amount gradually increased to 0.57 ± 0.01, 1.92 ± 0.07, and 6.90 ± 0.07% after the second, fourth and sixth MEP-treatments, respectively (Fig. 2d, Table 1, Supplementary Fig. S5a). Diversity indices, i.e., Chao1, Shannon and reciprocal Simpson, decreased after MEP-spraying (Supplementary Table S2), confirming that MEP treatment enhanced some specific groups of bacteria including Burkholderia and caused the decrease of soil microbial diversity. The qPCR analysis showed that the copy number of bacterial 16S rRNA genes was stable at around 2 × 1010 g−1-soil during the treatments (Supplementary Table S2). It should be noted here that the deep sequencing analysis demonstrated that the Burkholderia fraction in the soil is remarkably small, particularly in the early treatments, although they were abundant in the culture-dependent method (Fig. 2b).

Table 1.

Deep sequencing analysis of soil samples

| Experiment ID | Replicationa | No. of sequencesb | No. of Burkholderia sequences | Proportion of Burkholderiac | Proportion of Burkholderia group %d | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBE | Ambiguous A | BCC&P | Ambiguous B | PBE | Unmappedc | |||||

| 0S | 1 | 91,884 | 62 | 0.07 | 65.6 | 0 | 4.9 | 4.9 | 18.0 | 6.6 |

| 2 | 54,218 | 30 | 0.06 | 76.7 | 0 | 0 | 13.3 | 3.3 | 6.7 | |

| 3 | 85,407 | 60 | 0.07 | 76.7 | 0 | 1.7 | 5.0 | 15.0 | 1.7 | |

| 2S | 1 | 93,985 | 541 | 0.58 | 24.5 | 0 | 50.9 | 14.0 | 3.3 | 7.5 |

| 2 | 90,666 | 514 | 0.57 | 23.4 | 0 | 52.0 | 15.3 | 3.6 | 5.8 | |

| 3 | 98,302 | 539 | 0.55 | 31.6 | 0 | 45.0 | 15.6 | 3.4 | 4.4 | |

| 4S | 1 | 75,400 | 1371 | 1.8 | 18.7 | 0 | 3.0 | 14.3 | 62.6 | 1.3 |

| 2 | 94,871 | 1851 | 2.0 | 14.3 | 0 | 2.6 | 18.6 | 61.9 | 2.7 | |

| 3 | 92,846 | 1837 | 2.0 | 18.8 | 0 | 3.1 | 13.4 | 62.6 | 2.2 | |

| 6S | 1 | 128,961 | 9014 | 7.0 | 66.1 | 0 | 3.4 | 4.1 | 24.9 | 1.6 |

| 2 | 94,365 | 6424 | 6.8 | 65.5 | 0 | 4.1 | 2.1 | 26.6 | 1.8 | |

| 3 | 77,321 | 5330 | 6.9 | 61.0 | 0 | 4.1 | 3.0 | 29.7 | 2.3 | |

a Three replications were prepared for each MEP-spraying treatment

b Number of sequences after removal of low quality, chimeric, and archaeal sequences

c Proportion of Burkholderia sequences to bacterial seqeunces

d Proportion of sequences of each Burkholderia groups to Burkholderia seqeunces

Not unlike the result of the culture-dependent method (Fig. 2c), the deep sequencing analysis revealed that group-level and OTU-level compositions of Burkholderia dynamically changed during the treatments (Fig. 2e, Supplementary Fig. S5b): OTU15 in BCC&P firstly grew but then decreased until the fourth MEP-treatment; OTU25 in PBE dominated after the fourth treatment; and eventually OTU01 in SBE became dominant after the sixth treatment with MEP.

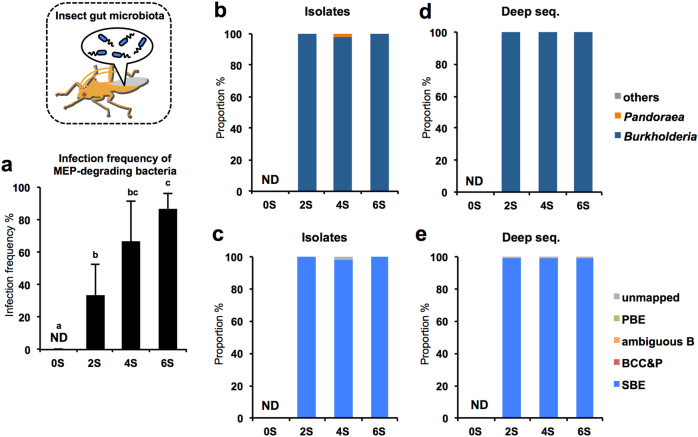

Bean bugs acquire MEP-degrading Burkholderia when reared on MEP-treated soils

Since the symbiotic organ of infected (symbiotic) insects is readily distinguishable from uninfected (aposymbiotic) ones by visual inspection [43] and by PCR amplification for bacterial 16S rRNA genes, the dissection of the insects and diagnostic PCR revealed that each individual from all soil samples was symbiotic (see below). The infection frequency of MEP-degrading bacteria was investigated by inspecting MEP-degrading activity of the dissected symbiotic organs using a spectrophotometric MEP-degradation assay. The result demonstrated that the infection frequency of MEP-degrading bacteria in the bean bug gradually increased depending on the frequency of MEP-spraying: bean bugs reared on untreated soils (0S) were all negative, while 33.3 ± 18.9, 66.7 ± 24.9, and 86.7 ± 9.4% (mean ± SD; n = 3) of insects reared on the two-, four-, and six-time-treated soils (2S, 4S, and 6S), respectively, were MEP-degradation positive (Fig. 3a).

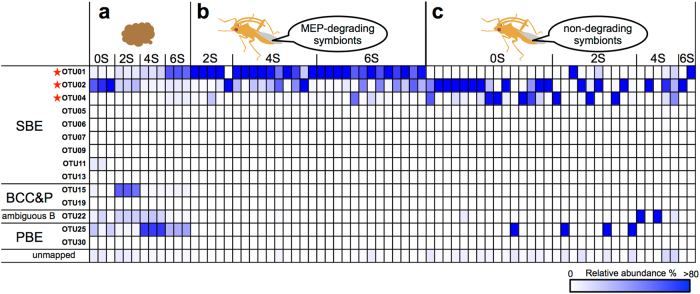

Fig. 4.

Dynamics of Burkholderia in MEP-sprayed soils and reared insects. Burkholderia OTUs in soils (a), in insects showing a MEP-degrading activity (b), and in insects showing no MEP-degrading activity (c). Based on deep sequencing analyses, Burkholderia dynamics in soils and insect-associated Burkholderia were compared in a heatmap. Within the currently identified Burkholderia species, 37 possible OTUs in total were generated by clustering the V4 region (255 bp) of 16S rRNA genes (>99.5% sequence identity). Of these 37 OTUs, 14 OTUs that include more than one mapped sequence were detected in this study. Sequences showing <99.5% identity are depicted as unmapped. A color gradient shows relative abundance of OTUs in a Burkholderia population within each sample. Stars indicate OTUs including MEP-degrading strains isolated from both insects and soils, among which OTU01 was the most abundant (see also Supplementary Fig. S2)

In a culture-dependent analysis of MEP-degradation positive insects, all isolated strains showed the MEP-degrading activity. They were subjected to direct sequencing of 16S rRNA genes for identification. In total, 260 colonies of MEP-degrading bacteria were isolated from 28 insects with 99.2% (258 colonies) belonging to the genus Burkholderia (Fig. 3b). Almost all of these MEP-degrading Burkholderia strains were placed into the SBE group (Fig. 3c). In total, 37 OTUs of Burkholderia were detected by clustering of reference sequences shown in Supplementary Table S1, among which OTU01 was by far the most prevalent throughout the rearing experiments (96.4% infection frequency; insects infected with OTU01/total insects infected with any MEP-degraders = 27/28) (Supplementary Fig. S2b).

Fig. 3.

Population dynamics of MEP-degrading bacteria in bean bug reared on MEP-sprayed soils. a Infection frequency of MEP-degrading bacteria in bean bugs when the insects were reared on MEP-sprayed soils. Five insects per soybean pot were subjected to a MEP-degradation assay. Mean ± SD (n = 3) is shown. Values with different letter are significantly difference (p > 0.05, ANOVA with Tukey’s honestly significant difference test). b, c Culture dependent analysis of MEP-degrading bacteria isolated from insects. From insects reared on 2, 4, and 6S pods, 47, 91, and 122 colonies were isolated and identified, respectively. d, e Culture independent analysis (deep sequencing) of gut microbiota of insects infected with MEP-degrading bacteria. Genus-level b, d and Burkholderia group-level (c, e) compositions are shown. Sequences showing <99.5% identity against reference Burkholderia sequences are depicted as “unmapped”. Data shown in d, e are averages; the corresponding data of all replicates is shown in Supplementary Fig. S5c and d. ND: not detected

Deep sequencing analysis of the symbiotic organs with MEP-degrading activity confirmed the extremely low-bacterial diversity and the predominance of SBE Burkholderia (Fig. 3d, e, Table 2, Supplementary Fig. S5c and d), which was different from soil microbiota (Supplementary Fig. S3b). Particularly, OTU01 of the SBE group was the most predominant phylotype in insects showing a MEP-degrading activity (Fig. 4), confirming the results of the culture-dependent analysis (Supplementary Fig. S2b). Although the sequenced region was limited to 255 bp, this sequence information was sufficient to distinguish the SBE, BCC&P and PBE clades (Supplementary Table S1). The deep sequencing data in conjunction with the culture-based results demonstrated that microbiota of the gut symbiotic organ with MEP-degrading activity was extremely simple, occupied with only a few OTUs of the SBE group.

Infection dynamics of MEP-degrading Burkholderia from soil to insect

Although Burkholderia dominated in both soil and insect, the population dynamics of the MEP-degrading Burkholderia showed a striking contrast between them; the OTU composition in the Burkholderia population dramatically changed in the MEP-sprayed soil, while the OTU associated with bean bugs was remarkably simple and stable during the series of experiments (Fig. 4a, b: compare Figs. 2e, 3e at the OTU level). The OTU-level comparison revealed OTU01 was the major MEP-degrading symbiont of bean bugs. Deep sequencing analysis revealed that relative abundance of OTU01 was extremely small, 0.004 ± 0.002% of the total analyzed bacterial population, in untreated soil, wherein the CFU of MEP-degrading bacteria was under the detection limit (<1.0 × 102 cfu g−1-soil). Relative abundance of the OTU01 was still very small, only 0.04 ± 0.01%, in the two-times-treated soil (2S); while the abundance of it increased to 0.24 ± 0.03% in the four-time-treated soil (4S) and eventually reached 3.49 ± 0.16% in the six-time-treated soil (6S).

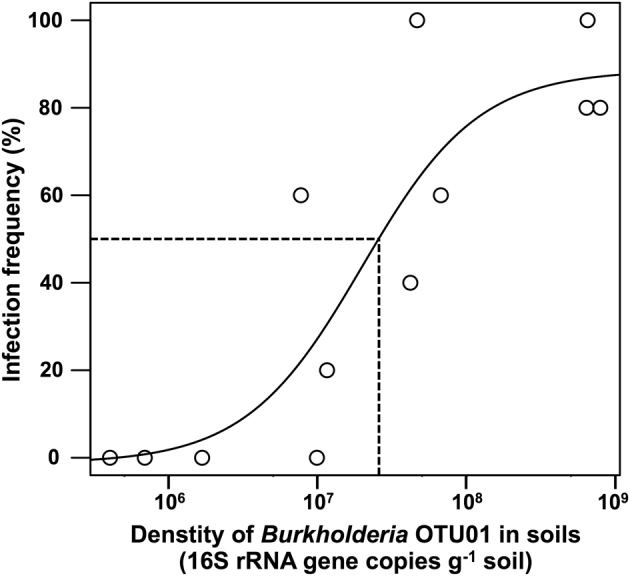

A notable conclusion of this data is that since insects carrying the OTU01 MEP-degrading symbiont appeared already after two-times spraying with MEP, the insect can acquire a MEP-degrading SBE (i.e., OTU01) from the ambient soil in which it is only present as a small fraction, 0.04 ± 0.01% of the bacterial population. The actual number of bacterial cells remains unknown, but considering the qPCR results of bacterial 16S rRNA genes (Supplementary Table S1) and deep sequencing results of the proportion of Burkholderia OTU01 in soil microbiota, the estimated copies number of 16S rRNA genes of the OTU01 was 9.7 ± 1.6 × 106 copies per g soil in 2S, 5.2 ± 1.1 × 107 copies per g soil in 4S, and 6.9 ± 0.7 × 108 copies g−1 soil in 6S. Together with the results of infection frequency of insects to Burkholderia OTU01 (Fig. 4), the 50% infective dose (ID50), defined as the amount of MEP-degrading Burkholderia OTU01 in soils required for colonization of 50% of tested insects, was estimated by sigmoid curve fitting as 2.0 × 107 copies per g soil (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Infective dose of a MEP-degrading Burkholderia (OTU01) in R. pedestris. The infection frequency of Burkholderia OTU01 in insects and the environmental density of it in soils were used to estimate the 50% infective dose (ID50) of the Burkholderia. The density of Burkholderia OTU01 was estimated by the copy number of bacterial 16S rRNA gene, and the relative abundance of OTU01 was determined by deep sequencing. Dotted lines indicate ID50 of Burkholderia OTU01

Infection dynamics of non-MEP-degrading Burkholderia in bean bugs

Apart from the insects infected with MEP-degrading symbionts, the other individuals were infected with non-MEP-degrading Burkholderia (Supplementary Fig. S6). In contrast to the infection frequency of MEP-degrading Burkholderia, infection frequency of non-degraders gradually decreased depending on the MEP-spraying (Supplementary Fig. S6a). In total, 32 insects infected with non-degraders were subjected to deep sequencing analysis. Burkholderia was detected from all of the 32 individuals (Supplementary Fig. S6b), although Pandoraea, a sister group of the genus Burkholderia, was predominant in three individuals. The non-degrading Burkholderia were mostly SBE, while some PBE- and ambiguous B-group Burkholderia were frequently detected in four and two individuals, respectively, (Supplementary Fig. S6). At the OTU level, OTU02 and OTU04 of the SBE group were predominant phylotypes in the insects infected with non-degrading Burkholderia (Fig. 4c). By contrast to the MEP-degrading symbiont OTU01, the OTU02 was detected frequently in the untreated soil (0S) but decreased after MEP-spraying (Fig. 4a), which corresponds to the gradual reduction of infection frequency of non-degrading Burkholderia in bean bugs (Supplementary Fig. S6a).

In this study, OTUs were assigned by only 255 bp sequences of 16S rRNA gene, which is the current technological limit in deep sequencing analysis. With such restricted information, genetically and phenotypically different strains could be assigned to the same OTU (Supplementary Table S1). In addition, since MEP-degrading genes are often encoded on a plasmid [33, 44–46], the MEP-degrading trait could be lost or gained via plasmid loss or transfer. In this context, it can be expected that genetically similar (or identical) phylotypes show different MEP-degrading activities. OTU02 and OTU04 were rare in the insects infected with MEP-degrading Burkholderia but predominant in insects infected with non-MEP-degrading Burkholderia (Fig. 4), suggesting that the majority of OTU02 and OTU04 are non-degrading. Similarly, culture-dependent and -independent results strongly suggested that the majority of OTU01 is MEP-degrading (Fig. 4; Supplementary Fig. S2).

Infection dynamics of MEP-degrading bacteria in crop fields

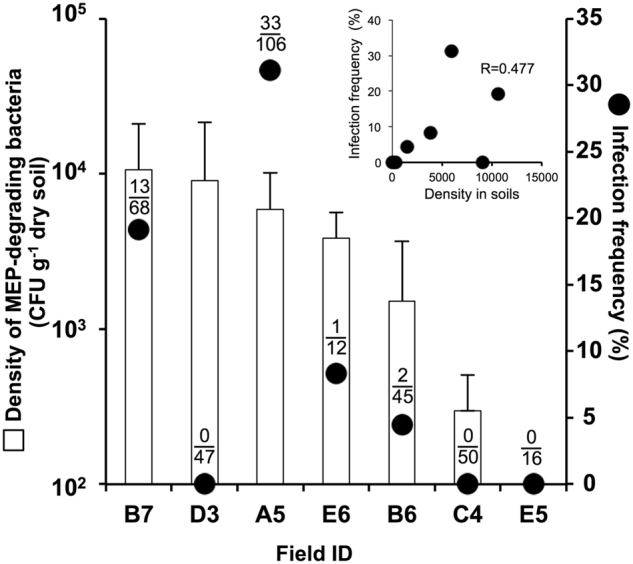

The soil-to-insect infection dynamics of MEP-degrading bacteria in crop fields were investigated in sugarcane fields in Minami-Daito Island. The CFU of MEP-degrading bacteria in field soils [34] and the infection frequency of MEP-degrading bacteria in field-collected C. saccharivorus (short-wing adults) were comparatively analyzed. The results were not entirely consistent but nevertheless showed a tendency of insects living on a soil inhabited by a high density of MEP-degraders being highly infected with MEP-degrading symbionts (Fig. 6).

Table 2.

Summary of deep sequencing analysis of insects’ gut samples

| Experiment ID | MEP-degrading activity | No. of insects | No. of total sequences | Proportion of Burkholderiaa | Proportion of Burkholderia group %b | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBE | ambiguous A | BCC&P | Ambiguous B | PBE | Unmappedc | |||||

| 0S | Positive | 0 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Negative | 15 | 28,452 ± 9387 | 99.9 ± 0.07 | 89.7 ± 24.0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 ± 1.7 | 6.1 ± 22.6 | 3.6 ± 2.2 | |

| 2S | Positive | 5 | 30,447 ± 6347 | 99.9 ± 0.04 | 99.5 ± 0.25 | 0 | 0 | 0.004 ± 0.002 | 0 | 0.48 ± 0.26 |

| Negative | 10 | 18,117 ± 10,865 | 54.3 ± 49.1 | 69.0 ± 43.6 | 0 | 0 | 0.40 ± 0.54 | 26.6 ± 40.7 | 3.93 ± 3.37 | |

| 4S | Positive | 10 | 29,331 ± 28,698 | 99.9 ± 0.06 | 99.0 ± 1.13 | 0 | 0 | 0.11 ± 0.32 | 0.007 ± 0.02 | 0.84 ± 0.82 |

| Negative | 5 | 14,018 ± 8933 | 60.7 ± 47.8 | 53.1 ± 43.3 | 0 | 0 | 41.5 ± 47.1 | 0.06 ± 0.10 | 5.34 ± 6.10 | |

| 6S | Positive | 13 | 26,123 ± 7899 | 99.9 ± 0.09 | 98.9 ± 1.62 | 0 | 0 | 0.005 ± 0.01 | 0.001 ± 0.003 | 1.09 ± 1.61 |

| Negative | 2 | 34,442 ± 12,105 | 99.9 ± 0.07 | 99.3 ± 0.53 | 0 | 0 | 0.004 ± 0.0001 | 0 | 0.74 ± 0.53 | |

aRatio of no. of Burkholderia sequences per no. of total sequences. The assignment was performed by the RDP classifier with a 80% confidence threshold

bRatio of no. of each group per no. of Burkholderia sequences. The assignment was perormed by BLAST-N search with >99.5% identity cutoff

cSequeces not assigned as any Burkholderia groups.

Fig. 6.

Infection dynamics of MEP-degrading bacteria from soil to insect in sugarcane fields. Closed circles indicate the infection frequency of the sugarcane pest bug, Cavelerius saccharivorus, with MEP-degrading bacteria. Numbers of infected insects/total insects investigated are depicted above the circle. Open bars indicate the CFU of MEP-degrading bacteria in field soils (referred from [34]). The inset shows the: correlation analysis between the density of MEP-degrading bacteria and the infection frequency of insects with MEP-degrading bacteria (R = 0.477, p = 0.279)

Discussion

We investigated how MEP spraying affected the dynamics of MEP-degrading bacteria in the soil and how this influenced the infection and acquisition of MEP-degrading symbionts by stinkbug hosts. Our study demonstrated that: (1) diverse strains of MEP-degrading Burkholderia dynamically change in soils depending on MEP-spraying frequency (Figs. 2e, 4); (2) among the diverse strains of MEP-degrading Burkholderia, a particular phylotype of the SBE group (OTU01) is nearly exclusively acquired by the bean bug (Fig. 4, Supplementary Fig. S2); (3) the specific infection and acquisition can occur after only two-times MEP spraying even though the relative abundance of the MEP-degrading phylotype is only 0.04 ± 0.01% in soil (estimated ID50: 2.0 × 107 copies of 16S rRNA genes g−1 soil) (Figs. 3, 4, 5); (4) as the abundance of the degrading strains increases in soil by spraying, the infection frequency of the MEP-degrading phylotype increases (Figs. 2a, 3a); and therefore, (5) the infection frequency of the MEP-degrading phylotype strictly depends on MEP-spraying and the resulting enrichment of the MEP-degrading symbiont in the soil. Furthermore, (6) the investigation of natural populations of a chinch bug strongly suggested that the density-dependent acquisition of MEP-degrading Burkholderia occurs in agricultural fields (Fig. 6). Population dynamics and succession of Burkholderia in soils after MEP spraying have been repeatedly studied by both culture-dependent and -independent approaches [29, 31, 34, 35, 47]; however, no study has investigated how such bacterial dynamics in soil under MEP-spraying condition influences the development of symbiont-mediated MEP resistance. This is, to our knowledge, the first clear-cut study demonstrating how environmental dynamics of bacteria affects the development of a symbiont-mediated and agriculturally important insect trait, insecticide resistance.

The evolution of insecticide resistance is generally considered to involve the modification of a pest’s own phenotype, in which the emergence of a resistance trait via mutation and/or rearrangement of the pest’s genome is selected by repeated application of the insecticide. The evolution of insecticide resistance is rather fast, but still requires several pest generations, even in the most rapid cases [48, 49]. Notably, infection with the MEP-degrading Burkholderia has been detected within 2 weeks after only two sprayings with MEP (Fig. 3a), suggesting that, via the intermediacy of MEP-degrading symbionts, insecticide resistance could evolve in a pest bug population more rapidly than was previously thought. This study has demonstrated that the symbiont-mediated insecticide resistance develops through two selection steps, i.e., selective growth of insecticide-degrading bacteria upon spraying and selective acquisition of symbionts by host insects, the development of which strongly depends on the first step occurring in bacteria in the soil. The rapid emergence of symbiont-mediated insecticide resistance after spraying could therefore be explained by the rapid evolution of soil bacteria.

In this study, two different stinkbug systems were investigated. In the laboratory experiments performed on the bean bug, as the density of MEP-degrading bacteria in soil increased from <102 to 104 cfu g−1 soil by two-times spraying of MEP, the infection frequency of MEP-degrading Burkholderia increased from 0 to 33.3 ± 18.9% (Figs. 2a, 3a). In the field survey of the chinch bug, in which the density of MEP-degrading bacteria in the soil ranged from 102 to 104 cfu g−1 soil, the infection frequency of MEP-degrading bacteria varied from 0 to 31.1% (Fig. 6). Despite the different systems, the similar soil-to-insect dynamics of MEP-degrading bacteria was observed, strongly suggesting that the relatively rapid evolution of insecticide resistance that we revealed by the laboratory experiments could also occur in natural crop fields. Based on these values, we here estimate that 102 cfu g−1 soil of MEP-degrading bacteria is a warning value for the emergence of symbiont-mediated insecticide resistance.

The enrichment of MEP-degrading bacteria in soils followed by the emergence of infected insects is most likely influenced by the spraying history of the insecticide. Our previous study revealed that MEP-degrading bacteria increase in response to MEP-spraying more quickly in soils with MEP-spraying history than in those without spraying history [29]. In such naive soils, infection of insects with MEP-degrading symbionts would be rare because of the low density of degrading symbionts present under the infection threshold, even after multiple sprayings. In contrast, sugarcane fields in Minami-Daito Island have been consistently treated with MEP and similar organophosphorus pesticides over 30 years. MEP-degrading bacteria naturally inhabit these soils and can be detected without the enrichment [34]. In such intensely-treated soils, insects could be infected with MEP-degrading bacteria without any additional spraying (Fig. 6), which illustrates in an agronomic setting the risk of insecticide resistance through the acquisition of symbionts.

The soil-to-insect infection dynamics of MEP-degrading Burkholderia (Fig. 4) indicates the remarkably high host-symbiont affinity between the bean bug and SBE group of Burkholderia. Our previous study revealed that R. pedestris acquires the Burkholderia symbiont extremely efficiently from the environment, with an ID50 of only 80 symbiont cells in rearing experiments [14]. Recently, we described a specific gut organ for bacteria sorting, the so-called “constricted region” in the insect’s midgut [36], by which the Burkholderia symbiont is exclusively selected from the enormously diverse soil microbiota. Although it remains unclear how specific the constricted region is in bacterial selection, it is plausible that this sorting mechanism is involved in the infection dynamics of MEP-degrading Burkholderia. Moreover, several bacterial adaptations have been identified that are essential for or contribute to the colonization of the symbiotic organ [36, 50–53], which should be involved in the specific and efficient acquisition of MEP-degrading Burkholderia.

This study analyzed the soil-to-insect infection process of MEP-degrading Burkholderia; then, is the reverse transmission of these MEP-degrading Burkholderia from insect to soil possible? Although it remains unclear whether the Burkholderia symbiont is released from the stinkbug host, the reverse transmission has been reported in other symbiotic systems with environmental transmission, such as the legume-Rhizobium and squid-Vibrio symbioses [54–56]. The release of MEP-degrading Burkholderia from stinkbugs would be of primordial importance in the development of symbiont-mediated insecticide resistance for the following two points. First, such infection-proliferation-escape process could increase the symbiont density in the environment, leading to high-infection fidelity. Second, since stinkbugs move actively from field to field, release of MEP-degrading symbionts from infected insects could lead to the spread of resistant insect metapopulations to fields without MEP-spraying history.

Conclusion

The arms race between pest insects and human invention of insecticides has intensified and has been a serious concern through our agricultural history, and in some cases remarkably rapid evolution of insecticide-resistance has been reported [57]. The rapid evolution of insect traits is generally thought to be determined by the insect’s genome, and the evolutionary process has been described only through the perspective of the insect’s population dynamics and genetics, while until now, symbiosis has not been considered. Diverse insect traits, such as food digestion, sex, heat tolerance and even body color, can be affected by symbiotic microorganisms [58–61]. Plants and soil on which insects inhabit are populated with an enormous quantity and diversity of microorganisms [62]. Hence, as shown here, environmental microorganisms could play a pivotal role in insect physiology, ecology, and evolution, as tightly associated microbiota do so. Now we should focus more on environmental microbial ecology to comprehensively understand and manage pest insects.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank Tomo Aoyagi, Ronald Navarro, and Natsuki Nakamura (AIST) for technical assistance, and Masanari Aizawa (Agrisupport Minami-Daito) for insect sampling. We also thank Peter Mergaert (CNRS) for insightful comments and English corrections. This study was supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT) KAKENHI (grant number 24117525 and 15H05638 for Y.K.).

Author contributions

H.I. and Y.K. designed the project. H.I. performed the insect rearing experiment. H.I., A.N., K.T., M.H., Y.S., and Y.K. collected the soil and insect samples. H.I., K.T., and M.H. conducted the culture dependent analysis. H.I., T.H., and Y.S. performed the deep sequencing analysis. H.I. analyzed the results. H.I. and Y.K. wrote the manuscript. All co-authors edited the manuscript before submission.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41396-017-0021-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Roush RT, McKenzie JA. Ecological genetics of insecticide and acaricide resistance. Annu Rev Entomol. 1987;32:361–380. doi: 10.1146/annurev.en.32.010187.002045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denholm I, Rowland MW. Tactics for managing pesticide resistance in arthropods: theory and practice. Annu Rev Entomol. 1992;37:91–112. doi: 10.1146/annurev.en.37.010192.000515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whalon ME, Mota-Sanchez D, Hollingworth RM. (2008). Global pesticide resistance in arthropods. Centre Agric Biosci Intl Oxfordshire, UK. Chapter 4, pp.40-89.

- 4.Kikuchi Y, Hayatsu M, Hosokawa T, Nagayama A, Tago K, Fukatsu T. Symbiont-mediated insecticide resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:8618–8622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200231109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramya SL, Venkatesan T, Murthy KS, Jalali SK, Varghese A. Degradation of acephate by Enterobacter asburiae, Bacillus cereus and Pantoea agglomerans isolated from diamondback moth Plutella xylostella (L), a pest of cruciferous crops. J Environ Biol. 2016;37:611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramya SL, Venkatesan T, Srinivasa Murthy K, Jalali SK, Verghese A. Detection of carboxylesterase and esterase activity in culturable gut bacterial flora isolated from diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella (Linnaeus), from India and its possible role in indoxacarb degradation. Braz J Microbiol. 2016;47:327–336. doi: 10.1016/j.bjm.2016.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xia X, Zheng D, Zhong H, Qin B, Gurr GM, Vasseur L, et al. DNA sequencing reveals the midgut microbiota of diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella (L.) and a possible relationship with insecticide resistance. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e68852. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trinder M, McDowell TW, Daisley BA, Ali SN, Leong HS, Sumarah MW, et al. Probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus reduces organophosphate pesticide absorption and toxicity to Drosophila melanogaster. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2016;82:6204–6213. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01510-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng D, Guo Z, Riegler M, Xi Z, Liang G, Xu Y. Gut symbiont enhances insecticide resistance in a significant pest, the oriental fruit fly Bactrocera dorsalis (Hendel) Microbiome. 2017;5:13. doi: 10.1186/s40168-017-0236-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ishikawa T, Takai M, Yasunaga T. A Field Guide to Japanese Bugs, Vol. 3. Tokyo: Zenkoku Noson Kyoiku Kyokai; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kikuchi Y, Hosokawa T, Fukatsu T. An ancient but promiscuous host–symbiont association between Burkholderia gut symbionts and their heteropteran hosts. ISME J. 2011;5:446–460. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim J, Lee B. Insect symbiosis and immunity: the bean bug–Burkholderia interaction as a case study. Adv Insect Phys. 2017;52:179–197. doi: 10.1016/bs.aiip.2016.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takeshita K, Kikuchi Y. Riptortus pedestris and Burkholderia symbiont: an ideal model system for insect–microbe symbiotic associations. Res Microbiol. 2016;168:175–187. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2016.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kikuchi Y, Yumoto I. Efficient colonization of the bean bug Riptortus pedestris by an environmentally transmitted Burkholderia symbiont. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:2088–2091. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03299-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kikuchi Y, Fukatsu T. Live imaging of symbiosis: spatiotemporal infection dynamics of a GFP-labelled Burkholderia symbiont in the bean bug Riptortus pedestris. Mol Ecol. 2014;23:1445–1456. doi: 10.1111/mec.12479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kikuchi Y. Endosymbiotic bacteria in insects: their diversity and culturability. Microbes Environ. 2009;24:195–204. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.ME09140S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kikuchi Y, Hosokawa T, Fukatsu T. Insect-microbe mutualism without vertical transmission: a stinkbug acquires a beneficial gut symbiont from the environment every generation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:4308–4316. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00067-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garcia J, Laughton A, Malik Z, Parker B, Trincot C, Chiang SL, et al. Partner associations across sympatric broad-headed bug species and their environmentally acquired bacterial symbionts. Mol Ecol. 2014;23:1333–1347. doi: 10.1111/mec.12655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Itoh H, Aita M, Nagayama A, Meng XY, Kamagata Y, Navarro R, et al. Evidence of environmental and vertical transmission of Burkholderia symbionts in the oriental chinch bug, Cavelerius saccharivorus (Heteroptera: Blissidae) Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80:5974–5983. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01087-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boucias DG, Garcia-Maruniak A, Cherry R, Lu H, Maruniak JE, Lietze VU. Detection and characterization of bacterial symbionts in the Heteropteran, Blissus Insul. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2012;82:629–641. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2012.01433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuechler SM, Matsuura Y, Dettner K, Kikuchi Y. Phylogenetically diverse Burkholderia associated with midgut crypts of spurge bugs, Dicranocephalus spp.(Heteroptera: Stenocephalidae) Microbes Environ. 2016;31:145–153. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.ME16042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olivier-Espejel S, Sabree ZL, Noge K, Becerra JX. Gut microbiota in nymph and adults of the giant mesquite bug (Thasus neocalifornicus) (Heteroptera: Coreidae) is dominated by Burkholderia acquired de novo every generation. Environ Entomol. 2011;40:1102–1110. doi: 10.1603/EN10309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gordon ERL, McFrederick Q, Weirauch C. Phylogenetic evidence for ancient and persistent environmental symbiont reacquisition in Largidae (Hemiptera: Heteroptera) Appl Environ Microbiol. 2016;82:7123–7133. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02114-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sudakaran S, Retz F, Kikuchi Y, Kaltenpoth M. Evolutionary transition in symbiotic syndromes enabled diversitification of phytophagous insects on an imbalanced diet. ISME J. 2015;9:2587–2604. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takeshita K, Matsuura Y, Itoh H, Navarro R, Hori T, Sone T, et al. Burkholderia of plant-beneficial group are symbiotically associated with bordered plant bugs (Heteroptera: Pyrrhocoroidea: Largidae) Microbes Environ. 2015;30:321–329. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.ME15153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stenersen J. Chemical pesticides: mode of action and toxicology. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kawahara K, Tanaka A, Yoon J, Yokota A. Reclassification of a parathione-degrading Flavobacterium sp. ATCC 27551 as Sphingobium fuliginis. J Gen Appl Microbiol. 2010;56:249–255. doi: 10.2323/jgam.56.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adhya T, Barik S, Sethunathan N. Hydrolysis of selected organophosphorus insecticides by two bacteria isolated from flooded soil. J Appl Bacteriol. 1981;50:167–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1981.tb00881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Itoh H, Navarro R, Takeshita K, Tago K, Hayatsu M, Hori T, et al. Bacterial population succession and adaptation affected by insecticide application and soil spraying history. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:457. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim KD, Ahn JH, Kim T, Park SC, Seong CN, Song HG, et al. Genetic and phenotypic diversity of fenitrothion-degrading bacteria isolated from soils. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;19:113–120. doi: 10.4014/jmb.0808.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tago K, Sekiya E, Kiho A, Katsuyama C, Hoshito Y, Yamada N, et al. Diversity of fenitrothion-degrading bacteria in soils from distant geographical areas. Microbes Environ. 2006;21:58–64. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.21.58. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Z, Hong Q, Xu J, Zhang X, Li S. Isolation of fenitrothion-degrading strain Burkholderia sp. FDS-1 and cloning of mpd gene. Biodegradation. 2006;17:275–283. doi: 10.1007/s10532-005-7130-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hayatsu M, Hirano M, Tokuda S. Involvement of two plasmids in fenitrothion degradation by Burkholderia sp. strain NF100. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:1737–1740. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.4.1737-1740.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tago K, Okubo T, Itoh H, Kikuchi Y, Hori T, Sato Y, et al. Insecticide-degrading Burkholderia symbionts of the stinkbug naturally occupy various environments of sugarcane fields in a Southeast island of Japan. Microbes Environ. 2015;30:29–36. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.ME14124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tago K, Kikuchi Y, Nakaoka S, Katsuyama C, Hayatsu M. Insecticide applications to soil contribute to the development of Burkholderia mediating insecticide resistance in stinkbugs. Mol Ecol. 2015;24:3766–3778. doi: 10.1111/mec.13265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ohbayashi T, Takeshita K, Kitagawa W, Nikoh N, Koga R, Meng XY, et al. Insect’s intestinal organ for symbiont sorting. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:E5179–E5188. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1511454112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fujisaki K. Ecological significance of the wing polymorphism of the oriental chinch bug, Cavelerius saccharivorus Okajima (Heteroptera: Lygaeidae) Res Popul Ecol. 1985;27:125–136. doi: 10.1007/BF02515485. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mahenthiralingam E, Urban TA, Goldberg JB. The multifarious, multireplicon Burkholderia cepacia complex. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:144–156. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sawana A, Adeolu M, Gupta RS. Molecular signatures and phylogenomic analysis of the genus Burkholderia: proposal for division of this genus into the emended genus Burkholderia containing pathogenic organisms and a new genus Paraburkholderia gen. nov. harboring environmental species. Front Genet. 2014;5:429. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2014.00429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suárez-Moreno ZR, Caballero-Mellado J, Coutinho BG, Mendonça-Previato L, James EK, Venturi V. Common features of environmental and potentially beneficial plant-associated Burkholderia. Microb Ecol. 2012;63:249–266. doi: 10.1007/s00248-011-9929-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peeters C, Meier-Kolthoff JP, Verheyde B, De Brandt E, Cooper VS, Vandamme P. Phylogenomic study of Burkholderia glathei-like organisms, proposal of 13 novel Burkholderia species and emended descriptions of Burkholderia sordidicola, Burkholderia zhejiangensis, and Burkholderia grimmiae. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:877. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Oevelen S, De Wachter R, Vandamme P, Robbrecht E, Prinsen E. ‘Candidatus Burkholderia calva’and ‘Candidatus Burkholderia nigropunctata’as leaf gall endosymbionts of African Psychotria. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2004;54:2237–2239. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.63188-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Futahashi R, Tanaka K, Tanahashi M, Nikoh N, Kikuchi Y, Lee BL, et al. Gene expression in gut symbiotic organ of stinkbug affected by extracellular bacterial symbiont. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e64557. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hernández-Mendoza A, Martínez-Ocampo F, Beltrán LFLA, Popoca-Ursino EC, Ortiz-Hernández L, Sánchez-Salinas E, et al. Draft genome sequence of the organophosphorus compound-degrading Burkholderia zhejiangensis strain CEIB S4-3. Genome Announc. 2014;2:e01323–01314. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01323-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lim JS, Choi BS, Choi AY, Kim KD, Kim DI, Choi IY, et al. Complete genome sequence of the fenitrothion-degrading Burkholderia sp. strain YI23. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:896–896. doi: 10.1128/JB.06479-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tago K, Yonezawa S, Ohkouchi T, Ninomiya T, Hashimoto M, Hayatsu M. A novel organophosphorus pesticide hydrolase gene encoded on a plasmid in Burkholderia sp. strain NF100. Microbes Environ. 2006;21:53–57. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.21.53. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tago K, Yonezawa S, Ohkouchi T, Hashimoto M, Hayatsu M. Purification and characterization of fenitrothion hydrolase from Burkholderia sp. NF100. J Biosci Bioeng. 2006;101:80–82. doi: 10.1263/jbb.101.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Georghiou GP. Overview of insecticide resistance. In: Green MB, LeBaron HM, Moberg WK, editors. Managing resistance to agrochemicals. Washington DC: American Chemical Society; 1990. pp. 18–41. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Levick B, South A, Hastings IM. A two-locus model of the evolution of insecticide resistance to inform and optimise public health insecticide deployment strategies. PLoS Comput Biol. 2017;13:e1005327. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim JK, Lee HJ, Kikuchi Y, Kitagawa W, Nikoh N, Fukatsu T, et al. Bacterial cell wall synthesis gene uppP is required for Burkholderia colonization of the stinkbug gut. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:4879–4886. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01269-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim JK, Won YJ, Nikoh N, Nakayama H, Han SH, Kikuchi Y, et al. Polyester synthesis genes associated with stress resistance are involved in an insect–bacterium symbiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:E2381–E2389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303228110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim JK, Am Jang H, Won YJ, Kikuchi Y, Han SH, Kim CH, et al. Purine biosynthesis-deficient Burkholderia mutants are incapable of symbiotic accommodation in the stinkbug. ISME J. 2014;8:552–563. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2013.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee JB, Byeon JH, Jang HA, Kim JK, Yoo JW, Kikuchi Y, et al. Bacterial cell motility of Burkholderia gut symbiont is required to colonize the insect gut. FEBS Lett. 2015;589:2784–2790. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nyholm SV, McFall-Ngai M. The winnowing: establishing the squid–Vibrio symbiosis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:632–642. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bright M, Bulgheresi S. A complex journey: transmission of microbial symbionts. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8:218–230. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Denison RF. Legume sanctions and the evolution of symbiotic cooperation by rhizobia. Am Nat. 2000;156:567–576. doi: 10.1086/316994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hartley C, Newcomb R, Russell R, Yong C, Stevens J, Yeates D, et al. Amplification of DNA from preserved specimens shows blowflies were preadapted for the rapid evolution of insecticide resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:8757–8762. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509590103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hurst GD, Jiggins FM, von der Schulenburg JHG, Bertrand D, West SA, Goriacheva II, et al. Male–killing Wolbachia in two species of insect. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1999;266:735–740. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1999.0698. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kikuchi Y, Tada A, Musolin DL, Hari N, Hosokawa T, Fujisaki K, et al. Collapse of insect gut symbiosis under simulated climate change. mBio. 2016;7:e01578–01516. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01578-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tsuchida T, Koga R, Horikawa M, Tsunoda T, Maoka T, Matsumoto S, et al. Symbiotic bacterium modifies aphid body color. Science. 2010;330:1102–1104. doi: 10.1126/science.1195463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Warnecke F, Luginbühl P, Ivanova N, Ghassemian M, Richardson TH, Stege JT, et al. Metagenomic and functional analysis of hindgut microbiota of a wood-feeding higher termite. Nature. 2007;450:560–565. doi: 10.1038/nature06269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tamames J, Abellán JJ, Pignatelli M, Camacho A, Moya A. Environmental distribution of prokaryotic taxa. BMC Microbiol. 2010;10:85. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-10-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.