Abstract

Background

Traditional public health surveillance provides accurate information but is typically not timely. New early warning systems leveraging timely electronic data are emerging, but the public health value of such systems is still largely unknown.

Objective

To assess the timeliness and accuracy of pharmacy sales data for both respiratory and gastrointestinal infections and to determine its utility in supporting the surveillance of gastrointestinal illness.

Methods

To assess timeliness, a prospective and retrospective analysis of data feeds was used to compare the chronological characteristics of each data stream. To assess accuracy, Ontario antiviral prescriptions were compared to confirmed cases of influenza and cases of influenza-like-illness (ILI) from August 2009 to January 2015 and Nova Scotia sales of respiratory over-the-counter products (OTC) were compared to laboratory reports of respiratory pathogen detections from January 2014 to March 2015. Enteric outbreak data (2011-2014) from Nova Scotia were compared to sales of gastrointestinal products for the same time period. To assess utility, pharmacy sales of gastrointestinal products were monitored across Canada to detect unusual increases and reports were disseminated to the provinces and territories once a week between December 2014 and March 2015 and then a follow-up evaluation survey of stakeholders was conducted.

Results

Ontario prescriptions of antivirals between 2009 and 2015 correlated closely with the onset dates and magnitude of confirmed influenza cases. Nova Scotia sales of respiratory OTC products correlated with increases in non-influenza respiratory pathogens in the community. There were no definitive correlations identified between the occurrence of enteric outbreaks and the sales of gastrointestinal OTCs in Nova Scotia. Evaluation of national monitoring showed no significant increases in sales of gastrointestinal products that could be linked to outbreaks that included more than one province or territory.

Conclusion

Monitoring of pharmacy-based drug prescriptions and OTC sales can provide a timely and accurate complement to traditional respiratory public health surveillance activities but initial evaluation did not show that tracking gastrointestinal-related OTCs were of value in identifying an enteric disease outbreak in more than one province or territory during the study period.

Introduction

In Canada, traditional public health surveillance of infectious diseases relies heavily on the reporting of laboratory-confirmed cases. This mechanism provides robust information, but may be accompanied by an appreciable lag period between testing and reporting of illness to public health authorities. This results in a lost window of opportunity for implementing interventions. Furthermore, for infectious diseases typically associated with mild to moderate illness, treatment is often empiric (i.e., no testing is done) which limits the ability of laboratory-based surveillance to provide an accurate assessment of illness in the community.

Syndromic surveillance often involves Big Data; it is based on the use of non-specific health indicators or proxy measures (e.g., school absenteeism, drug sales, tele-health calls) to provide a provisional diagnosis (or "syndrome"). These data sources tend to be non-specific yet sensitive and rapid and can augment and complement the information provided by traditional diagnostic test-based surveillance systems (1).

Over the past 10 years, pharmacy-based surveillance has emerged as a new public health capability in Canada and internationally (2-5). The Public Health Agency of Canada (the Agency) first deployed a pharmacy-based syndromic surveillance in 2004 to evaluate the feasibility of monitoring gastrointestinal over-the-counter (OTC) products as a tool in the early detection of community food and waterborne illness and outbreaks. In 2009, pharmacy-based syndromic surveillance was again used by the Agency in response to the influenza H1N1 pandemic (pH1N1) outbreak. A retrospective analysis of the second wave of pH1N1 demonstrated that pharmacy-based surveillance provided an effective mechanism to monitor and detect influenza-like activity and was faster than traditional surveillance systems (6).

Following the H1N1 pandemic, the pharmacy-based surveillance system was extended to determine utility during implementation of the Agency’s Surveillance Strategic Plan. A number of medications were tracked, including analgesics, anti-allergy medications and prescriptions of antidepressants and cardiovascular medications.

The objective of this study was to evaluate three aspects of this system: the accuracy, timeliness and utility of pharmacy-based surveillance to support seasonal influenza and respiratory illness surveillance and detection of multijurisdictional enteric disease outbreaks (i.e., involving more than one province or territory).

Methods

Data sources

Data was obtained for respiratory surveillance on antiviral prescriptions in Ontario (2009-2015) and respiratory OTCs in Nova Scotia (2014-2015). These were compared with confirmed cases of influenza and reports of influenza-like-illness in Ontario and laboratory detections of non-influenza respiratory pathogens in Nova Scotia.

Data was obtained for gastrointestinal surveillance on OTC sales of products indicated for acute gastrointestinal illness across Canada and data from Nova Scotia was compared with local outbreak data reported to provincial health authorities.

Data collection and reporting

Pharmacy data acquisition was established through a contract with an industry partner, Rx Canada. Daily prescription sales data were sourced from 13 national pharmacy chains and four independents, representing over 3,000 stores nationwide. Over-the-counter (OTC) data were provided daily by six chain retailers representing 1,863 stores across Canada (excluding Nunavut). Both OTC and prescription datasets provided coverage for over 85% of the health regions across Canada.

Pharmacy products were categorized into syndromes by grouping products into respiratory or gastrointestinal categories. OTC sales data were standardized by store prior to aggregating by health unit, province/territory and nationally to minimize the effect of varying transmission frequency and timeliness between stores and retail chains. The proportion of daily sales of select products indicated for acute enteric illness was calculated and presented over sales of all other OTC products. The standardized seven-day moving average of gastrointestinal sub-categories divided by other OTCs was graphed on a log scale. A simple alert algorithm based on 1, 2 and 3 standard deviations above the seven-day moving average was used to detect aberrant increases in pharmacy sales.

Timeliness

Prospective and retrospective analysis of the various data feeds leveraged in this study (OTC, prescriptions, ILI, laboratory reporting) were compared to assess the timeliness of public health surveillance.

Accuracy

Accuracy of pharmacosurveillance for influenza and influenza-like illness was assessed by a retrospective analysis comparing pharmaceutical and surveillance data. Surveillance data was extracted from the FluWatch Surveillance System. Five years of prescription antiviral sales in Ontario were compared to reported cases of influenza-like-illness (ILI) between August 2009 and January 2015 and to confirmed cases of influenza between 2011 and 2015. Together with descriptive analysis, Spearman correlation coefficients (rho) were determined for three time frames (January to December, November to March and April to October).

To assess tracking accuracy for other respiratory infections, weekly provincial laboratory detections of respiratory viral pathogens from Nova Scotia reported between January 2014 and March 2015 were evaluated relative to sales of respiratory over-the-counter products for the same period. Respiratory OTC data were aggregated by week and one-to-five week lag variables were created. Correlations using Pearson’s coefficients were calculated between respiratory OTC sales, non-influenza Respiratory Viral Detections (RVD) and tests for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).

To assess the accuracy of enteric pharmacosurveillance, sales of gastrointestinal OTCs were compared with enteric outbreak data from Nova Scotia between 2011 and 2014 using descriptive analysis.

Utility

Pharmacy surveillance reports based on the pharmacy sales of gastrointestinal products across Canada were generated and disseminated weekly to provincial and territorial stakeholders and included province and health region-level information and trends. The usefulness of the reported information to stakeholders was evaluated using a survey developed using FluidSurvey.

SAS 9.3 and Stata 13 were used for running analytical procedures.

Results

Timeliness

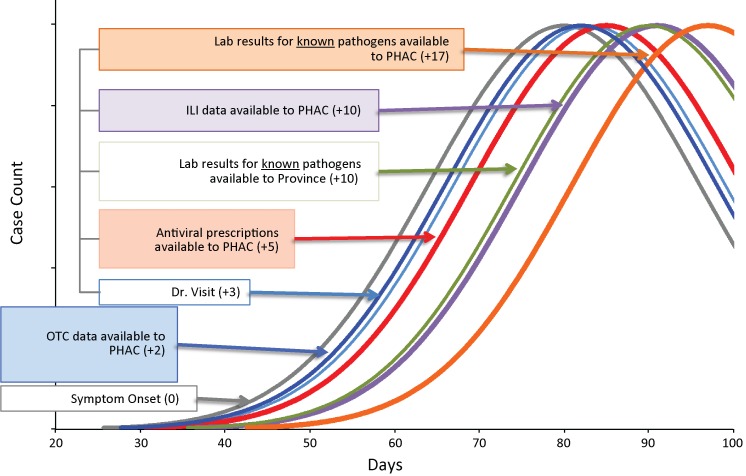

Pharmacy sales data (i.e., prescription medication, OTC products) were available in near real-time; approximately 48 hours after a completed transaction. Pharmacy sales data were available to the Agency approximately five to eight days earlier than ILI physician reports, 10-12 days prior to laboratory confirmations of influenza, and up to 17 days earlier than reports of respiratory viral detections. Figure 1 depicts the timelines of pharmacy, clinical and laboratory data relative to the estimated onset of illness and the availability of the information for the purpose of respiratory surveillance.

Figure 1. Timeliness of Severe Respiratory Disease Surveillance.

ILI: Influenza-like-illness PHAC: Public Health Agency of Canada OTC: Over-the-counter

Accuracy

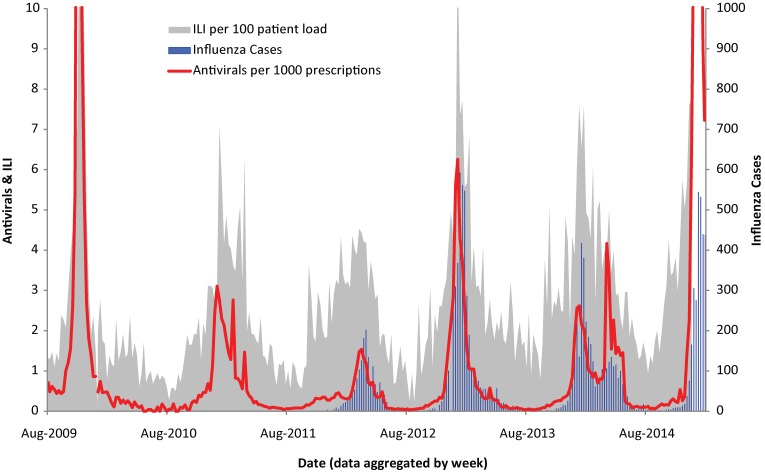

Respiratory surveillance: Weekly dispensed prescriptions of the antiviral medications oseltamivir and zanamivir, as a proportion of all dispensed prescriptions, were compared with the rate of ILI (cases of ILI/total patient visits) and the number of confirmed laboratory reports of influenza in Ontario (Figure 1). Sales of antivirals between 2009 and 2015 correlated closely with the onset dates of confirmed influenza cases. Spearman’s rhos were 0.90, 0.93 and 0.83 (all at p < 0.001) for January to December, November to March and April to October respectively. In addition, the magnitude of antiviral sales paralleled the burden of confirmed cases. The correlation coefficient between confirmed cases and ILI was not as strong comparably. For January and December the rho was 0.80, in November and March the rho was 0.70 and from April to October the rho was 0.60. Reports of ILI followed the same trends of confirmed cases and antivirals, (Figure 2) however, ILI varied considerably in late spring and summer.

Figure 2. Ontario influenza cases, antiviral prescriptions and ILI1.

1ILI: Influenza-like-illness

Results of the Nova Scotia analysis demonstrated sales of respiratory OTC products associated with increases in non-influenza respiratory pathogens in the community (respiratory syncytial virus, rhinovirus, coronavirus, parainfluenza, adenovirus, human metapneumovirus). OTC sales correlated with the number of RSV tests four weeks later (r=0.76, p < 0.001). Sales of OTC products correlated with the number of other respiratory viral detections two weeks later (0.74, p < 0.001) (Figure 2).

Gastrointestinal surveillance: There were 262 outbreaks reported in Nova Scotia between 2012 and 2014. Of these, 66% of outbreaks were due to norovirus; 82% of outbreaks were primarily person-to-person transmission and the majority (81%) of outbreaks occurred in residential institutions. There were no definitive correlations detected between the occurrence of outbreaks and sales of gastrointestinal OTCs.

Utility

During the pilot phase, no significant increases in sales of gastrointestinal products were detected that could be definitively linked to any multijurisdictional enteric outbreak. Although only 40% of stakeholders responded to the evaluation survey, most (87%) indicated that the pharmacy information was important to their jurisdiction. Five jurisdictions stated that they had used the information. Of these 20% used it to initiate an investigation, 75% to detect a health event, 20% communicated the information to clinicians and all used it for situational awareness.

Discussion

National and provincial pharmacosurveillance appeared to be more useful for early detection of respiratory illness than for provincial detection of enteric disease. Antiviral prescriptions were a clear marker of influenza activity for respiratory illness surveillance. The value of respiratory-related OTCs was less clear, but they may be useful in the surveillance of other respiratory viruses. Although the sales of gastrointestinal products have been shown to be a good marker for seasonal community norovirus infections (6), the value of pharmacosurveillance for outbreak-related enteric activity was less certain.

Strengths of this study include the national representativeness of the data and the precise documentation of pharmacosurveillance data timeliness. One potential weakness is that it included only prescribed medications and OTCs from retail pharmacies not linked to health care institutions. For example, although Nova Scotia enteric outbreak data were robust, the majority of norovirus outbreaks captured during the study period occurred in long-term care facilities. Medications provided to long-term care facilities may have originated from pharmacies not contributing sales data to the pharmacy pilot project or perhaps bulk purchases by long-term care facilities were simply not captured in the data provided.

Automated data transfer from point of sale supports real or near real-time acquisition of community-specific health data. Pharmacy prescription and OTC sales data provide greater timeliness and higher geographic resolution and national coverage than other health data currently used. Pharmacy sales data has been shown to support seasonal influenza and aid in decision-making for resource allocation. Prescription and OTC data also provide an earlier window of opportunity for intervention compared to using traditional data sources only. Furthermore, pharmacy data could be used to support surveillance and action for multiple public health purposes (e.g., mental health, physician prescription patterns and chronic illness) and by multiple agencies and different jurisdictions. As with other surveillance systems, investments in the necessary technological and analytical resources are required to conduct ongoing pharmacy-based syndromic surveillance.

Conclusion

Timely and accurate pharmacosurveillance has the potential to enhance public health capacity to detect and quantify activity at the local, multijurisdictional and national level. Further research is needed to determine under which conditions it is most useful and to compare it against other real-time surveillance strategies.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the provinces and territories for providing case data for the analysis and participating in the pilot study and those at Flu Watch for providing the respiratory surveillance data. The strong commitment and support of the Chain Retailers, pharmacy stores and Rx Canada was pivotal in the success of the various phases of the Pharmacy-based Syndromic Surveillance pilot.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: Jeffery Aramini works for Intelligence Health Solutions, the company that provided the analysis for the data.

Funding: Support and funding of the of the pharmacosurveillance project was provided by the Public Health Agency of Canada

References

- 1.Berger M, Shiau R, Weintraub JM. Review of syndromic surveillance: implications for waterborne disease detection. J Epidemiol Community Health 2006. Jun;60(6):543–50. 10.1136/jech.2005.038539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chadwick D. The Rhode Island Department of Health. The first statewide system for tracking disease using prescription data. Press Release Archives. State of Rhode Island. Department of Health. 2009. http://www.ri.gov/press/view/10017 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pavlin JA, Murdock P, Elbert E, Milliken C, Hakre S, Mansfield J et al. Conducting population behavioral health surveillance by using automated diagnostic and pharmacy data systems. MMWR Suppl 2004. Sep;53:166–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sugawara T, Ohkusa Y, Ibuka Y, Kawanohara H, Taniguchi K, Okabe N. Real-time prescription surveillance and its application to monitoring seasonal influenza activity in Japan. J Med Internet Res 2012. Jan;14(1):e14. http://www.jmir.org/2012/1/e14/ 10.2196/jmir.1881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van den Wijngaard CC, van Pelt W, Nagelkerke NJ, Kretzschmar M, Koopmans MP. Evaluation of syndromic surveillance in the Netherlands: its added value and recommendations for implementation. Euro Surveill 2011. Mar;16(9):19806. http://www.eurosurveillance.org/images/dynamic/EE/V16N09/art19806.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aramini J, Muchaal PK, Pollari F; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Value of pharmacy-based influenza surveillance - Ontario, Canada, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2013. May;62(20):401–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]