Abstract

Objective

To evaluate Ontario’s provincial varicella vaccination program through analysis of aggregate varicella cases in order to determine whether there has been a decrease in reportable disease burden; and to assess varicella vaccine adverse events following immunization (AEFIs).

Methods

Aggregate varicella cases (1993−2013) were extracted from the reportable disease databases. Pre-program (1993−2004) and post-program (2007−2013) periods were chosen according to implementation of the publicly funded vaccination program. AEFIs following administration of varicella vaccines (2010−2013) were also extracted. Reporting rates were calculated using net doses distributed as the denominator. Serious AEFIs were defined using World Health Organization standards.

Results

The incidence of aggregate varicella reports decreased significantly over the study period (from 311.4 to 22.2 cases per 100,000 population in 1993 and 2013, respectively). Incidence also decreased significantly in all age groups between the pre- and the post-program periods with a shift in age distribution towards older individuals in the post-program period. A total of 162 AEFIs following varicella vaccine were reported between 2010 and 2013 for an annualized reporting rate of 14.6 per 100,000 doses distributed. The most common events were rash (37.3%), including eight reports of varicella-like rash (0.7 per 100,000 doses distributed). Ten serious events were reported (0.9 per 100,000 doses distributed), and all vaccine recipients recovered.

Conclusion

Significant reductions in varicella disease incidence and low AEFI reporting rates were observed with the introduction of the publicly funded varicella vaccine program in Ontario. Continued surveillance is indicated to further assess trends in varicella disease and vaccine safety.

Introduction

Varicella, commonly known as chickenpox, is a primary infection caused by the varicella-zoster virus (VZV). Prior to the introduction of varicella vaccines, chickenpox was considered a ubiquitous disease of childhood affecting 90% of children by 12 years of age (1). Before varicella vaccines were available in Canada, approximately 350,000 varicella cases occurred each year with over 1,550 hospitalizations annually for all ages between 1994 and 2000 (1). In addition, 59 varicella-related deaths were reported throughout the country between 1987 and 1997 (1).

Live, attenuated varicella vaccine was first authorized for use in Canada in 1998, and was available for private purchase in Ontario (2). In September 2004, a single dose of varicella vaccine (Varilrix® [GlaxoSmithKline−GSK] or Varivax® III [Merck]) was added to Ontario’s publicly funded immunization schedule for children 15 months of age. In August 2011, a second dose was added to the provincial schedule, administered as measles-mumps-rubella-varicella (MMRV) vaccine (Priorix-Tetra® [GSK]) at 4 to 6 years of age (3). In addition, children born on or after January 1, 2000, who were at least 1 year of age were eligible for a second dose of varicella vaccine (4). One-dose varicella vaccine coverage was 77.8% among 5-year-olds in Ontario based on coverage assessment of school pupils for the 2012−2013 school year (5).

With the implementation of universal childhood varicella immunization programs, a decrease in disease incidence and varicella-related hospitalizations has been observed in Canada (6−10) and the United States (11−14). Decreases in varicella incidence and morbidity have also been observed in Australia and some European countries (e.g., Germany; parts of Italy and Spain) after the implementation of varicella vaccination programs (15−17). Extensive post-marketing surveillance of varicella vaccine safety over almost two decades has demonstrated an excellent safety profile where the majority of reported events are mild, including fever, rash and injection site reactions, and serious events are rare (18−21).

Assessment of immunization coverage, disease surveillance and vaccine safety data are essential components of comprehensive immunization program evaluation. Our objective is to evaluate the provincial varicella vaccination program through the analysis of aggregate reports of varicella cases throughout the period of program implementation, from 1993 to 2013; and the assessment of adverse events reported following administration of varicella-containing vaccines administered in Ontario between 2010 and 2013.

Methods

In Ontario, reporting of varicella and adverse events following immunization (AEFIs) to the local medical officer of health is mandated by provincial public health legislation. Local public health units (PHUs) investigate reports and enter information according to provincial surveillance guidelines into the integrated Public Health Information System (iPHIS), the electronic reporting system for reportable diseases and AEFIs in Ontario. Varicella is reported as both individual cases and in aggregate numbers in iPHIS. All PHUs are required to report monthly aggregate counts by predefined age groups, as well as individually reporting cases that are laboratory-confirmed, hospitalized or have specified complications, including death (22,23). Aggregate cases do not contain individual-level case details; they contain only information on age group, PHU, year and month of reporting. Herpes zoster is not a reportable disease in Ontario.

Aggregate varicella reporting

Our analyses were limited to aggregate cases of varicella reported between January 1993 and December 2013. Individually reported cases of varicella were not included in the study. We extracted aggregate cases reported between 1993 and 2004 from the Ontario Public Health Portal on May 24, 2012, and aggregate cases reported between 2007 and 2013 from iPHIS on July 16, 2014. We excluded cases from 2005 and 2006 due to data completeness issues arising from transition in Ontario’s reportable disease databases (from the Reportable Disease Information System to iPHIS). We selected pre- (1993−2004) and post- (2007−2013) publicly funded program periods based on the dates of implementation of the publicly funded varicella vaccination program in Ontario. The pre-program period includes time when varicella vaccine was available for private purchase, but not publicly funded (excluding the last four months of 2004). Incidence rate ratios (IRRs) were calculated to examine the changes in disease incidence between the two periods (i.e., the incidence rate in the post-program period divided by the incidence rate in the pre-program period). Trends in incidence rate over the entire study period were assessed using Poisson regression.

Adverse events following immunization

On April 28, 2014, we extracted from iPHIS all AEFIs reported following administration of varicella-containing vaccines (monovalent varicella vaccines and MMRV vaccine) between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2013. Descriptive analyses were limited to “confirmed” AEFIs which are defined as events that follow immunization which cannot be attributed to other causes. A causal relationship with the vaccine does not need to be proven.

Each AEFI report represents one vaccine recipient and one or more adverse events temporally associated with receipt of one or more vaccines. Adverse events were grouped by provincial case definitions. We selected age categories for analysis based on the recommended routine varicella immunization schedule (3). Reporting rates are calculated using net doses distributed within the publicly funded program as the denominator. We defined serious AEFIs using the Public Health Agency of Canada AEFI reporting guidelines which are based on the World Health Organization standard definition (25,26). We conducted a key-word search of narrative case notes to identify varicella- or zoster-like rashes. Monovalent varicella and MMRV vaccine AEFIs are presented separately.

We performed statistical analyses using SAS (Statistical Analysis System) version 9.3 and Microsoft Excel 2010; p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Aggregate varicella reporting

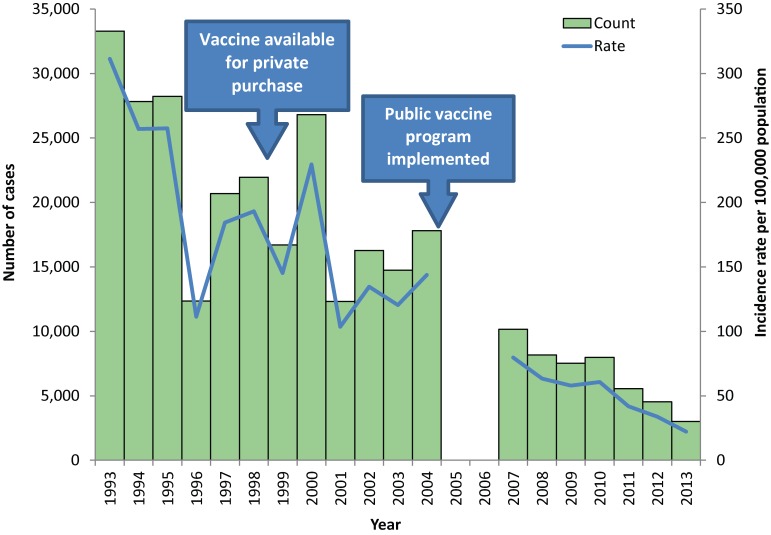

Between January 1993 and December 2013, a total of 295,928 aggregate varicella cases were reported in Ontario. Varicella incidence decreased significantly over the study period from 311.4 cases per 100,000 population in 1993 to 22.2 cases per 100,000 population in 2013 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Number of aggregate varicella cases and incidence in Ontario, 1993−2013 (n=295,928)

Between the pre- and post-program periods, the overall incidence of varicella decreased from 180.5 to 51.0 cases per 100,000 population, for an IRR of 0.28 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.28−0.29]. There was also a decrease in age-specific incidence which was significant in all age groups. The largest decline was observed in children in the 1- to 4-year-old age group, followed by the 5- to 9- and less than 1-year-old age groups (Table 1). In terms of age distribution, the 5- to 9-year-old age group continued to have the highest proportion of total varicella cases (57% in both periods); however, a shift in distribution towards older individuals was noted in the post-program period. Between the two periods, the proportion of cases among the 10- to 14-year-olds increased from 10.8% to 19.8%, while the proportion among the 1- to 4-year-olds decreased from 26.1% to 15.8%.

Table 1. Varicella incidence rate ratios comparing the pre-program period to the post-program period, by age group in Ontario, 1993−2013.

| Age group (years) | Pre-program incidence (per 100,000 population) | Post-program incidence (per 100,000 population) | Incidence rate ratio (95% confidence interval) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 180.5 | 51.0 | 0.28 (0.28−0.29) |

| <1 | 137.1 | 50.3 | 0.37 (0.33−0.40) |

| 01−04 | 899.9 | 183.9 | 0.20 (0.20−0.21) |

| 05−09 | 1,506.3 | 520.6 | 0.35 (0.34−0.35) |

| 10−14 | 282.0 | 167.6 | 0.59 (0.58−0.61) |

| 15−19 | 58.1 | 21.2 | 0.36 (0.34−0.39) |

| ≥20 | 6.5 | 2.7 | 0.41 (0.39−0.43) |

Adverse events following immunization

Monovalent varicella vaccine AEFIs

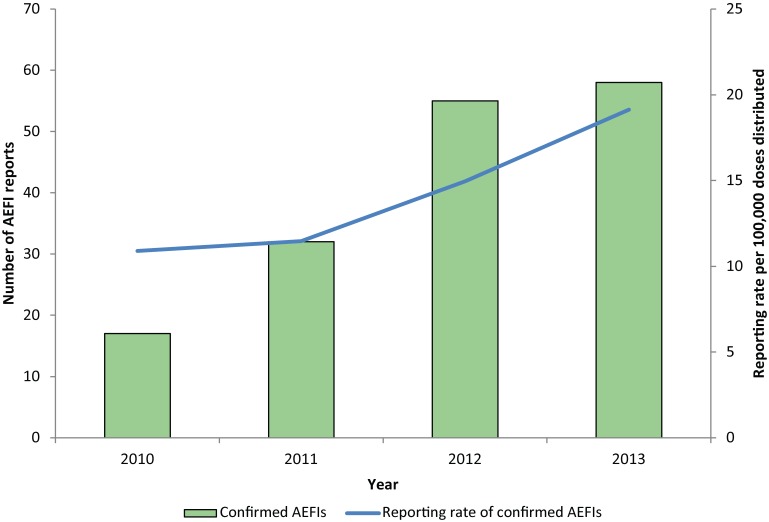

There were 162 confirmed AEFIs reported following administration of monovalent varicella vaccine and 1,106,143 doses of varicella vaccine distributed between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2013. The annualized reporting rate was 14.6 per 100,000 doses distributed, and steadily increased from 10.9 per 100,000 doses distributed in 2010 to 19.1 per 100,000 doses distributed in 2013 (Figure 2). The age range was from 9 months to 70 years (median: 4.5 years); 38.9% of reports occurred in children between 12 and 23 months of age. Overall, 52.5% of AEFI reports were female; however, among adults over 18 years, 92.9% (n=13) were female.

Figure 2.

Number of AEFIs reported following administration of monovalent varicella vaccines and reporting rate per 100,000 doses distributed in Ontario, by year, 2010−2013

Monovalent varicella vaccines were administered alone in 62.3% (n=101) of reports. Rash was the most commonly reported event (37.3%), followed by pain, redness or swelling at the injection site (32.9%) (Table 2). Key-word searching of case notes identified eight reports that described varicella-like rashes—all following the first dose of vaccine with a median time to onset of 7.5 days (range: 2 to 17 days). Seven of these events occurred in children between 12 and 23 months of age and one occurred in an adolescent; none were laboratory-confirmed. There was also one report of laboratory-confirmed herpes zoster infection in a toddler with zoster-like symptoms 6.5 months after the first dose of vaccine. Genotyping confirmed vaccine-strain varicella zoster virus isolated from a skin specimen.

Table 2. Number and distribution of varicella vaccine AEFIs in Ontario, by adverse event category, 2010−2013.

| Adverse event category1 | Adverse event2 | All AEFI reports n (%)3 | Serious AEFIs n (%)4 | Reporting rate (per 100,000 doses distributed) | Serious reporting rate (per 100,000 doses distributed) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allergic events | Total | 37 (23.0) | 2 (5.4) | 3.3 | 0.2 |

| • Allergic reaction—other | 2 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0.2 | 0 | |

| • Allergic reaction—skin | 33 (20.5) | 1 (3.0) | 3.0 | 0.1 | |

| • Event managed as anaphylaxis | 2 (1.2) | 1 (50) | 0.2 | 0.1 | |

| Injection site reactions | Total | 76 (47.2) | 2 (2.6) | 6.9 | 0.2 |

| • Cellulitis | 18 (11.2) | 2 (11.1) | 1.6 | 0.2 | |

| • Infected abscess | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0.1 | 0 | |

| • Sterile abscess | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0.1 | 0 | |

| • Nodule | 10 (6.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0.9 | 0 | |

| • Pain/redness/swelling | 53 (32.9) | 0 (0.0) | 4.8 | 0 | |

| Neurologic events | Total | 6 (3.7) | 4 (66.7) | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| • Convulsions/seizures | 5 (3.1) | 3 (60.0) | 0.5 | 0.3 | |

| • Encephalopathy/encephalitis | 1 (0.6) | 1 (100.0) | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Other events of interest | Total | 14 (8.7) | 1 (7.1) | 1.3 | 0.1 |

| • Arthritis/arthralgia | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0.1 | 0 | |

| • Syncope with injury | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0.1 | 0 | |

| • Other severe/unusual events | 12 (7.5) | 1 (8.3) | 1.1 | 0.1 | |

| Systemic events | Total | 69 (42.9) | 5 (7.2) | 6.2 | 0.5 |

| • Fever ≥38°C | 18 (11.2) | 4 (22.2) | 1.6 | 0.4 | |

| • Persistent crying/screaming | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0.1 | 0 | |

| • Rash | 60 (37.3) | 1 (1.7) | 5.4 | 0.1 | |

| • Severe vomiting/diarrhea | 2 (1.2) | 1 (50.0) | 0.2 | 0.1 |

1Adverse event categories represent groupings of specific types of adverse events and are not mutually exclusive. For category totals, reports with more than one specific event within a category are counted only once. Thus category totals will not be the sum to the total of specific adverse events overall or within a category. 2Includes only those adverse events where the count was at least one. 3Each AEFI report may contain one or more specific adverse events which are not mutually exclusive. Percentages will not sum to 100%. The denominator of 162 is the total number of confirmed varicella AEFI reports between 2010 and 2013. The specific type of adverse event was missing for one report in 2011, and thus was excluded from the total confirmed AEFI reports in this specific analysis (n=161). 4Percent of reports that were serious within each event.

MMRV vaccine AEFIs

There were eight confirmed AEFI reports following MMRV vaccine administered between August 8, 2011, and December 31, 2013. The reporting rate was 8.7 per 100,000 doses distributed. The median age was 5 years (range: 1 to 10 years). MMRV vaccine was administered alone in four of the eight reports. The most common events were injection site reactions (n=4) and allergic reactions (n=2) (including one anaphylaxis); none were serious.

Discussion

This analysis found a significant reduction in varicella disease incidence at a population level and a low AEFI reporting rate following the introduction of the publicly funded varicella vaccine program in Ontario.

Aggregate varicella reporting

Aggregate reporting of varicella was valuable in describing the overall trends in the epidemiology of disease in Ontario, despite data limitations described further below. The significant decrease in varicella incidence over the study period is consistent with findings observed in the U.S (27,28), and suggests that the publicly funded immunization program has had a positive impact on reducing varicella disease incidence in Ontario. This is further demonstrated by comparing the pre- and post-program periods, where the incidence was over three and a half times higher in the pre-program period than in the post-program period. It should also be noted that the pre-program period includes the years when the varicella vaccine was available for private purchase in Canada (1998−2004) which is a conservative measure as it would minimize the magnitude of decrease in disease incidence between the pre- and the post-program periods if a decrease in disease burden occurred as a result of private vaccine availability. Although the trends in varicella-associated health care utilization were out of scope for this analysis, the decrease in disease incidence mirrors the trends in decreasing varicella-associated hospitalizations observed in Canadian provinces, including Ontario (7−9). Furthermore, the declining incidence observed across all age groups, including those not targeted by the publicly funded immunization program (i.e., infants under 1 year of age), suggests a herd effect.

We would expect that a toddler vaccination program would change the age distribution of disease by shifting the burden of disease towards older individuals. In both the pre- and post-program periods, the majority of the varicella cases were observed among the 5- to 9-year-old age group. However, in the post-program period, more cases were reported in the 10- to 14-year-old age group than in the 1- to 4-year-old age group, in contrast to what was observed in the pre-program period. We may continue to see this shift in age distribution in the future as both the vaccinated cohort and the population with naturally-acquired immunity age, and as varicella vaccine coverage of the younger cohort increases. The significant decrease in varicella incidence since the implementation of the two-dose program in 2011 warrants further consideration on future requirements for varicella reporting in Ontario.

Reported adverse events following immunization

AEFIs reported following varicella-containing vaccines administered in Ontario between 2010 and 2013 were consistent with the safety profile of varicella vaccines with no identification of any safety signals. The overall reporting rate of AEFIs following varicella vaccine (14.6 per 100,000 doses distributed) was comparable to reporting rates following other childhood vaccines administered in the second year of life in Ontario (29); however, it is lower than the AEFI reporting rates for varicella vaccine from the Canadian Adverse Events Following Immunization Surveillance System (CAEFISS) (74.0 per 100,000 doses distributed) (30), as well as passive AEFI surveillance systems in the U.S. and Europe (30.0 and 52.7 per 100,000 doses distributed, respectively) (19,20). The increase in the number of AEFI reports between 2010 and 2013 was anticipated given the expansion of the varicella immunization program in 2011.

Reported events were mostly mild (e.g., injection site reactions) and, as expected, rash was the most commonly reported event (37.3% of reports) which is consistent with observations from the U.S. and Europe (32.6% and 25.7%, respectively) (19,20). Among all rashes, we identified a subset as varicella-like (vesicular) rash through key-word searching, although it is not clear if these were due to wild-type or vaccine strain as none were laboratory-confirmed. In addition, we identified a single report of laboratory-confirmed vaccine-strain herpes zoster, an event which, while rare, has consistently been noted in post-marketing surveillance reports (18−21). Serious AEFI reports were infrequently reported and were generally related to known, but rare, reactions to varicella vaccine, including cerebellar ataxia, which has been reported following both wild-type varicella infection and after varicella vaccine administration (18-21,31). The reporting rate of cerebellar ataxia following varicella vaccine was low (0.18 per 100,000 doses distributed), and similar to the rates from other post-marketing surveillance systems (18-20). No new or previously unknown serious events were reported.

Findings on MMRV vaccine are limited due to the low distribution of MMRV vaccine in the publicly funded program to date. As the use of this vaccine increases, an increase in AEFI reporting is expected and will contribute towards further understanding of the safety profile of this vaccine in Ontario.

Limitations

Some limitations are inherent to many passive surveillance systems, including missing/incomplete data, reporting bias and under-reporting. In addition, the scope of this analysis is limited to only two out of three components of a comprehensive immunization program evaluation.

In terms of aggregate varicella reporting, under-reporting due to failure to report at the parent, physician, and/or PHU level would underestimate the burden of varicella in Ontario; however, the degree of under-reporting is not known. Additionally, because cases reported in aggregate cannot be reconciled with individual-level data (e.g., laboratory results, immunization data), data may include misclassified cases and some duplicate cases reported from more than one source. However, it is difficult to estimate the significance of duplicates and case misclassification without individual-level data.

For AEFI surveillance data, there was limited comparison to baseline rates, limited temporal trend analysis and lack of a population-based immunization registry. In addition, it has been noted elsewhere (29) that Ontario’s overall AEFI reporting rate is less than half the national AEFI reporting rate, which is likely related to some degree of under-reporting as well as differences in AEFI reporting requirements in Ontario compared with other jurisdictions. With respect to varicella vaccine, pre-vaccination counselling about expected events following vaccine may also result in under-reporting of mild reactions specifically (i.e., fever, rash, injection site reactions), some of which are reportable as AEFIs in Ontario.

Conclusion

Varicella disease incidence was significantly reduced following the introduction of the publicly funded varicella vaccine program in Ontario and no safety signals were identified. These findings contribute towards varicella immunization program evaluation in Ontario which is essential to ensure the continued success of the program. Surveillance is ongoing to further assess trends in varicella disease and AEFI reporting in the context of the recent change from a one- to a two-dose schedule.

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our sincere thanks to public health unit staff across the province for their efforts in investigation and reporting of varicella and adverse events following immunization which are essential to the assessment of the publicly funded program and vaccine safety in Ontario.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None

Funding: Funding for this project was provided by Public Health Ontario.

References

- 1.Public Health Agency of Canada. Varicella (Chickenpox). Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada; 2012 [updated 2012 Jul 23]. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/im/vpd-mev/varicella-eng.php

- 2.National Advisory Committee on Immunization. Varicella vaccination two-dose recommendations. Can Commun Dis Rep 2010;36(ACS-8):1–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Publicly Funded Immunization Schedules for Ontario—August 2011. Toronto, ON: Queen's Printer for Ontario; 2011 [updated 2011 Aug 1;]. http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/public/programs/immunization/docs/schedule.pdf

- 4.Publicly Funded Immunication Schedules for Ontario—August 2011. Questions and Answers for Health Care Providers. Toronto, ON: Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care [updated 2011 Aug 10]. http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/immunization/docs/qa_schedule.pdf

- 5.Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion (Public Health Ontario). Immunization coverage report for school pupils: 2012−13 school year. Toronto, ON: Queen’s Printer for Ontario; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Russell ML, Svenson LW, Yiannakoulias N, Schopflocher DP, Virani SN, Grimsrud K. The changing epidemiology of chickenpox in Alberta. Vaccine 2005. Nov;23(46-47):5398–403. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwong JC, Tanuseputro P, Zagorski B, Moineddin R, Chan KJ. Impact of varicella vaccination on health care outcomes in Ontario, Canada: effect of a publicly funded program? Vaccine 2008. Nov;26(47):6006–12. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fardeau de la varicelle et du zona au Québec,1990−2008: impact du programme universel de vaccination. Québec, QC: Institut national de santé publique du Québec, Gouvernement du Québec; 2011 Apr. https://www.inspq.qc.ca/pdf/publications/1355_FardeauVaricelleZona1900-2008ImpactUnivVaccin.pdf

- 9.Tan B, Bettinger J, McConnell A, Scheifele D, Halperin S, Vaudry W et al. ; Members of the Canadian Immunization Monitoring Program, Active (IMPACT). The effect of funded varicella immunization programs on varicella-related hospitalizations in IMPACT centers, Canada, 2000-2008. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2012. Sep;31(9):956–63. 10.1097/INF.0b013e318260cc4d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Waye A, Jacobs P, Tan B. The impact of the universal infant varicella immunization strategy on Canadian varicella-related hospitalization rates. Vaccine 2013. Oct;31(42):4744–8. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.08.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seward JF, Watson BM, Peterson CL, Mascola L, Pelosi JW, Zhang JX et al. Varicella disease after introduction of varicella vaccine in the United States, 1995-2000. JAMA 2002. Feb;287(5):606–11. 10.1001/jama.287.5.606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reynolds MA, Watson BM, Plott-Adams KK, Jumaan AO, Galil K, Maupin TJ et al. Epidemiology of varicella hospitalizations in the United States, 1995-2005. J Infect Dis 2008. Mar;197 Suppl 2:S120–6. 10.1086/522146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guris D, Jumaan AO, Mascola L, Watson BM, Zhang JX, Chaves SS et al. Changing varicella epidemiology in active surveillance sites--United States, 1995-2005. J Infect Dis 2008. Mar;197 Suppl 2:S71–5. 10.1086/522156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chaves SS, Lopez AS, Watson TL, Civen R, Watson B, Mascola L et al. Varicella in infants after implementation of the US varicella vaccination program. Pediatrics 2011. Dec;128(6):1071–7. 10.1542/peds.2011-0017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khandaker G, Marshall H, Peadon E, Zurynski Y, Burgner D, Buttery J et al. Congenital and neonatal varicella: impact of the national varicella vaccination programme in Australia. Arch Dis Child 2011. May;96(5):453–6. 10.1136/adc.2010.206037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carville KS, Riddell MA, Kelly HA. A decline in varicella but an uncertain impact on zoster following varicella vaccination in Victoria, Australia. Vaccine 2010. Mar;28(13):2532–8. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.01.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.European Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (ECDC). Varicella vaccine in the European Union. Stockholm, Sweden: ECDC; 2014 Apr. http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/Varicella-guidance-2014-consultation.pdf

- 18.Sharrar RG, LaRussa P, Galea SA, Steinberg SP, Sweet AR, Keatley RM et al. The postmarketing safety profile of varicella vaccine. Vaccine 2000. Nov;19(7-8):916–23. 10.1016/S0264-410X(00)00297-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chaves SS, Haber P, Walton K, Wise RP, Izurieta HS, Schmid DS et al. Safety of varicella vaccine after licensure in the United States: experience from reports to the vaccine adverse event reporting system, 1995-2005. J Infect Dis 2008. Mar;197 Suppl 2:S170–7. 10.1086/522161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goulleret N, Mauvisseau E, Essevaz-Roulet M, Quinlivan M, Breuer J. Safety profile of live varicella virus vaccine (Oka/Merck): five-year results of the European Varicella Zoster Virus Identification Program (EU VZVIP). Vaccine 2010. Aug;28(36):5878–82. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.06.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galea SA, Sweet A, Beninger P, Steinberg SP, Larussa PS, Gershon AA et al. The safety profile of varicella vaccine: a 10-year review. J Infect Dis 2008. Mar;197 Suppl 2:S165–9. 10.1086/522125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Infectious Diseases Protocol. Appendix A: Disease-Specific Chapters. Chapter: Varicella (Chickenpox). Toronto, ON: Queen’s Printer for Ontario; 2014 Jan. http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/publichealth/oph_standards/docs/chickenpox_chapter.pdf

- 23.Infectious Diseases Protocol. Appendix B: Provincial Case Definitions for Reportable Diseases. Disease: Varciella (Chickenpox). Toronto, ON: Queen’s Printer for Ontario; 2014 Jan. http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/publichealth/oph_standards/docs/chickenpox_cd.pdf

- 24.Infectious Diseases Protocol. Appendix B: Provincial Case Definitions for Reportable Diseases. Disease: Adverse Events Following Immunization (AEFIs). Toronto, ON: Queen’s Printer for Ontario; 2015 Apr http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/publichealth/oph_standards/docs/aefi_cd.pdf

- 25.International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use. ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline. Post-Approval Safety Data Management: Definitions and Standards for Expedited Reporting. E2D. Geneva: International Conference on Harmonisation; 2003 Nov 12. http://www.ich.org/fileadmin/Public_Web_Site/ICH_Products/Guidelines/Efficacy/E2D/Step4/E2D_Guideline.pdf

- 26.International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use. ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline. Clinical Safety Data Management: Definitions and Standards for Expedited Reporting. E2A. Geneva: International Conference on Harmonisation; 1994 Oct 27. http://www.ich.org/fileadmin/Public_Web_Site/ICH_Products/Guidelines/Efficacy/E2A/Step4/E2A_Guideline.pdf

- 27.Baxter R, Ray P, Tran TN, Black S, Shinefield HR, Coplan PM et al. Long-term effectiveness of varicella vaccine: a 14-Year, prospective cohort study. Pediatrics 2013. May;131(5):e1389–96. 10.1542/peds.2012-3303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bialek SR, Perella D, Zhang J, Mascola L, Viner K, Jackson C et al. Impact of a routine two-dose varicella vaccination program on varicella epidemiology. Pediatrics 2013. Nov;132(5):e1134–40. 10.1542/peds.2013-0863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion (Public Health Ontario). Annual report on vaccine safety in Ontario, 2013. Toronto, ON: Queen’s Printer for Ontario; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Law BJ, Laflèche J, Ahmadipour N, Anyoti H. Canadian Adverse Events Following Immunization Surveillance System (CAEFISS): annual report for vaccines administered in 2012. Can Commun Dis Rep 2014;40 S-3:7–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuter B, Matthews H, Shinefield H, Black S, Dennehy P, Watson B et al. ; Study Group for Varivax. Ten year follow-up of healthy children who received one or two injections of varicella vaccine. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2004. Feb;23(2):132–7. 10.1097/01.inf.0000109287.97518.67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]